Abstract

Background

Non-adherence impacts negatively on patient health outcomes and has associated economic costs. Understanding drivers of treatment adherence in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases is key for the development of effective strategies to tackle non-adherence.

Objective

To identify factors associated with treatment non-adherence across diseases in three clinical areas: rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

Design

Systematic review.

Data Sources

Articles published in PubMed, Science Direct, PsychINFO and the Cochrane Library from January 1, 1980 to February 14, 2014.

Study Selection

Studies were eligible if they included patients with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or psoriasis and included statistics to examine associations of factors with non-adherence.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by the first reviewer using a standardized 23-item form and verified by a second/third reviewer. Quality assessment was carried out for each study using a 16-item quality checklist.

Results

73 studies were identified for inclusion in the review. Demographic or clinical factors were not consistently associated with non-adherence. Limited evidence was found for an association between non-adherence and treatment factors such as dosing frequency. Consistent associations with adherence were found for psychosocial factors, with the strongest evidence for the impact of the healthcare professional–patient relationship, perceptions of treatment concerns and depression, lower treatment self-efficacy and necessity beliefs, and practical barriers to treatment.

Conclusions

While examined in only a minority of studies, the strongest evidence found for non-adherence were psychosocial factors. Interventions designed to address these factors may be most effective in tackling treatment non-adherence.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0256-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Patient adherence, Psoriasis, Psoriatic arthritis, Rheumatology

Introduction

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) refer to a group of chronic conditions that share common inflammatory pathways [1]. IMIDs include conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), psoriasis (PS) and rheumatologic conditions (RC) including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). IMIDs affect approximately 5–7% of Western populations and can have a detrimental effect on quality of life and health outcomes [1]. In line with other chronic conditions, sub-optimal adherence to treatment has been reported in a number of systematic reviews. Persistence or adherence rates to treatments for IMIDs were found to range from 30% to 80% in RA [2], 7% to 72% in IBD [3], and 33% to 78% in PS [4].

Increasing adherence may have a far greater impact on health outcomes than advances in medical treatments [5, 6]. There are also associated economic implications such as increased medication costs, resources used including hospital admissions, inadequate use of healthcare professionals’ time, and increased sickness-related work absence [7]. Thus, understanding the key drivers of non-adherence to the types of treatments used across IMIDs is an important area of investigation and key for the development of effective strategies to tackle non-adherence. Further, the identification of generic tools and/or interventions common to IMIDs would enable the identification of key areas likely to be important for adherence and assist the clinician to identify and address patient concerns in their consultations.

Although there are existing systematic reviews looking at factors associated with non-adherence in the individual clinical areas (i.e., RA, IBD, or PS), there is a clear need for a broad understanding of the determinants of adherence across IMIDs [2–4, 8–19].

Aims

To our knowledge, no systematic review to date has examined factors associated with adherence across several IMIDs or included multiple treatment types. The purpose of the current review is, therefore, to examine factors associated with adherence in selected IMIDs across rheumatology, gastroenterology and dermatology in a systematic way. This could enable the identification of associations not only in each therapeutic area but also those in common across the therapeutic areas. Identification of key factors will allow interventions to focus on areas most likely to have an impact on non-adherence. If there are factors that are found to be common across these IMIDs, this will afford the opportunity to develop cross-condition tools for the health care professional (HCP) both to identify areas of non-adherence risk and for generic interventions, which may be particularly useful for rheumatologists who are likely to treat patients with different manifestations of their IMIDs.

Methods

The systematic review followed guidelines developed by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York [18, 19].

Literature Search and Selection

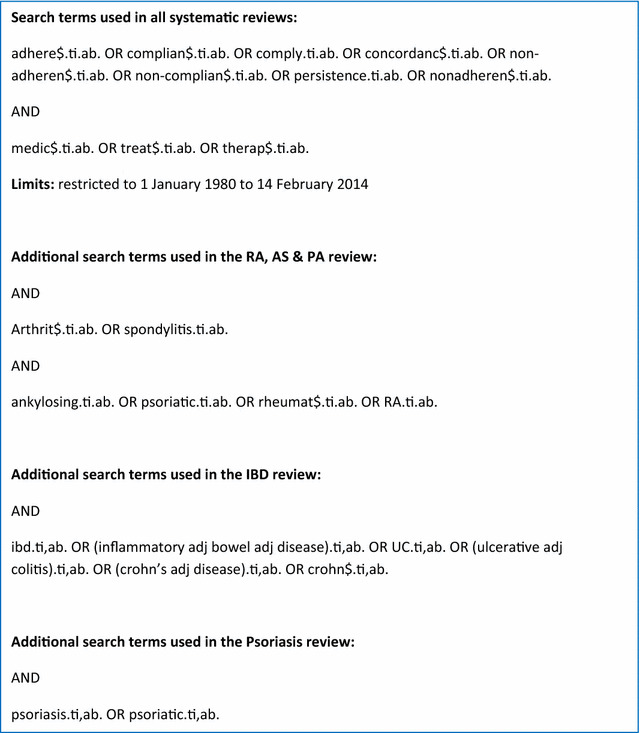

A search of the literature was conducted via the following online databases: PubMed, Science Direct, PsychINFO and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials. A broad search strategy was developed to capture each disease within the examined clinical areas (see Fig. 1). In addition, the reference lists of relevant articles identified through the database search and existing systematic reviews were searched manually to identify further suitable studies. The search was limited to articles published from January 1, 1980 to February 14, 2014. The reason for limiting the search to articles published after January 1980 was that a previous systematic review identified that general research interest in treatment adherence began around 1980 [3].

Fig. 1.

Search terms

The search was conducted individually for each of the selected IMIDs within the five clinical areas: RA, AS, PsA and IBD and PS. Initially, the titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the search strategies were screened by a first reviewer for eligibility (SB, AF or DB). The full text was then obtained for all shortlisted studies and independently reviewed by a second reviewer (AB). Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and independently assessed by a third reviewer (EV or JW).

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they met all the criteria below:

Published/in press between January 1, 1980 and February 14, 2014.

Written in English language.

Included patients with a diagnosis of RA, AS or PsA, IBD, or PS.

Based primarily on adult samples (≥18 years).

Included statistics to examine associations of factors with non-adherence.

Used a specified measure of adherence (validated or non-validated).

Included adherence measurement of injection or infusion, oral, rectal or transdermal formulation (excluding parenteral nutrition).

Contained primary quantitative data.

All participants were on a disease-specific treatment.

Full study published in a peer-review journal (i.e., not a conference abstract).

Studies in other clinical indications were included as long as specific information on one of the conditions of interest was explicit within the results. The decision was taken to exclude studies examining adherence to topical treatments alone, as topical treatments are not used across all three clinical areas and are typically prescribed in mild cases of PS only.

Quality Appraisal

Quality assessment was carried out for each study to examine their susceptibility to bias in terms of rigor, methods and analysis. A 16-item quality checklist adapted from a previous systematic review of a similar nature [3] based on guidance from NICE and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology was completed for each study. Although studies were not excluded or ranked according to quality, an overall quality score, based on the total number of quality criteria met, was computed for each study. Quality scores were used as general indicators for each study and are presented in the overview tables of included studies. Common quality limitations are explored in more detail in the “Results” section.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Studies identified through each individual search were combined for data synthesis and extraction. For each eligible study, data were extracted by the first reviewer using a standardized form consisting of 23 items, which included details of measures that could potentially relate to non-adherence. Details of the sample, non-adherence measure and potential associates examined were extracted and tabulated by the first reviewer and verified by the second and third reviewers. There was an 85% initial agreement in the data extracted and all discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the reviewers.

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis of the findings. Frequencies and proportions of studies examining similar variables and any association observed were calculated to offer a simple indication of the level of evidence. As such, the evidence was primarily synthesized in a narrative review and quantified in terms of the proportions of studies finding an association. As no two studies controlled for the same variables and the quality of these studies varied considerably, preference was not given to findings from adjusted analyses. Where associations were found for a factor and these were all in the same direction, the association was considered to be consistent.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Included Studies

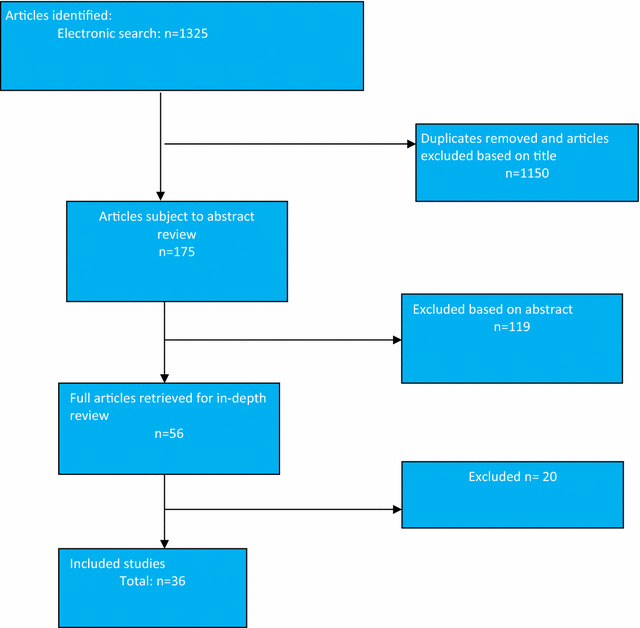

A total of 73 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the combined review: RC = 26 (RA = 23; AS = 1; PsA = 11); IBD = 36; PS = 11 [20–92]. Details regarding the study selection and exclusion process followed are presented in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. A summary of the characteristics of the studies and the factors examined in each study are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3 Studies from the same authors were checked for overlapping samples, and where there was overlap in the samples, the studies examined different possible predictors of adherence [69, 70].

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of included studies: rheumatologic conditions, reasons for exclusion of final 27 studies included: did not statistically examine factors associated with adherence (n = 8, original search) (n = 7, update search), full study data not reported (n = 1, original search), did not define measure of adherence (n = 9, original search) (n = 1, update search), intervention examined in relation to adherence (n = 1, original search)

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of included studies: inflammatory bowel disease, reasons for exclusion of final 20 studies included: did not statistically examine factors associated with adherence (n = 10, original search) (n = 1, update search), did not define measure of adherence (n = 5, original search), intervention examined in relation to adherence (n = 2, original search), adherence examined in sample of pregnant women only (n = 2, original search)

Fig. 4.

Flowchart of included studies: psoriasis reasons for exclusion of final 19 studies included: did not statistically examine factors associated with adherence (n = 7, original search) (n = 6, update search), examined topical treatments only (n = 5, original search), intervention examined in relation to adherence (n = 1, original search)

Table 1.

Overview of included studies: rheumatologic conditions

| Authors and year | Sample characteristics, origin, and design | Factors measured | Analysis | Non-adherence: target, measure and extent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Clinical | Treatment | Psychosocial | |||||

| Arturi et al. (2013) |

Sample: AS and RA outpatients N: 59AS and 53RA Mean age: AS: 47 (IQR = 33–57) Mean age: RA: 56 (IQR = 43.5–60) Male-AS: 73% Male-RA: 30% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 5/16 (31%) |

For AS and RA patients: age, gender, education insurance, employment |

For AS & RA patients Disease duration, Disease activity, Functional capacity, co-morbidities |

Both AS and RA patients: medication type |

For AS only: Depression |

Univariate and multivariate | Target |

NSAIDs, Low dose oral steroids, DMARDs, aTNF |

| Measure | Compliance questionnaire on Rheumatology (CQR) | |||||||

| Extent |

RA: 7% AS: 25% |

|||||||

| Beck et al. (1988) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 63 Mean age: 57.0 (SD = NR) Male: information not provided Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 12/16 (75.0%) |

Age, educational level | Symptoms (pain) | Treatment dose (last and total), treatment cost, size of last meal, side effects, treatment coating, time since last treatment | Intentions (appointment keeping, treatment termination, medication taking), pain reduction, rarely missing school, rarely missing work, accessibility (ease and length of time), follow through on commitments | Multivariate | Target | NSAID (Salicylate drugs) |

| Measure | Serum salicylate assays | |||||||

| Extent | 50.7% | |||||||

| Borah et al. (2009) |

Sample: Medical claims database (RA) N: 3829 Mean age: 54 (SD = 12) Male: 25% Origin: US Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 7/11 (63.6%) |

Medication type | Univariate and Multivariate | Target | Etanercept, adalimumab | |||

| Measure | Medication possession ratio (pharmacy claims data). Non- adherent classed as MPR <80% | |||||||

| Extent | 45.7% | |||||||

| Brus et al. (1999) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 65 Mean age: 58.8 (SD = 12.1) Male: 32% Origin: The Netherlands Design: RCT Quality: 10/16 (62.5%) |

Age, gender, education level | Symptoms (pain), functional disability, disease activity | Self-efficacy, treatment efficacy, environmental influences, practical barriers, social support | Univariate and multivariate | Target | DMARDS (Sulfasalazine therapy (SSZ)) | |

| Measure | Pill counts and pharmacy refills | |||||||

| Extent |

9% (SD = 12)—intervention group 13% (SD = 22) control group |

|||||||

| Caplan et al. (2013) |

Sample: Cohort of RA patients from ongoing longitudinal study N: 6052 Mean age: 63.8 (SD = 12.17) Male: 19.7% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 6/16 (37.5%) |

Age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, education, income | Functional status, visual problems, co-morbidities, disease duration | Medication type | Memory problems, lifestyle (smoking), health literacy, social support | Multivariate | Target | Prednisone, biologic treatment, DMARD |

| Measure | Medication adherence self-report inventory (MASRI) visual analog scale. Good adherence: 80–120% in the last month | |||||||

| Extent | 20.4 | |||||||

| Chastek et al. (2012) |

Sample: PsA patients: claims data from commercial health plan N: 346 Mean age: E: 45.6 (SD = 10.9) Mean age: A: 45.0 (SD = 10.3) Male: E 56.4% Male-A: 56.9% Origin: USA Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 7/12 (58.3%) |

Medication type | Univariate | Target | Etanercept or adalimumab | |||

| Measure | Persistence: continuous use of index medication without gaps in therapy of at least 60 days | |||||||

| Extent |

Non-persistence: 50% etanercept 55% adalimumab |

|||||||

| Cho et al. (2012) |

Sample: RA patients: NHI claims database N: 388 Mean age: 50.6 (SD = 14.9) Male: 17.5% Origin: Korea Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 7/12(58.3%) |

Gender, age, insurance type |

Co-morbidities, institution type (tertiary, regional, or general hospitals), physician type (internist versus other specialties) |

Medication type | Depression | Target | Adalimumab, etanercept, inFLiximab | |

| Measure | Non-persistence: a period longer than 14 weeks without a claim submitted for TNF inhibitors | |||||||

| Extent |

Non-persistence: 27% at 12 months 39% at 18 months |

|||||||

| Curkendall et al. (2008) |

RA population: Commercial insurance claims from the MEDSTAT MarketScan Database N: 2285 Mean age: 54 (SD = 12) Male: 25% Origin: US Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 8/11 (72.7%) |

Gender, region, HMO insurance | Multivariate | Target | Etanercept, adalimumab | |||

| Measure | Medication possession ratio (pharmacy refill data) | |||||||

| Extent |

Mean score (SD) 0.52 (0.31) |

|||||||

| de Klerk et al. (2003) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 81 Mean age: 60 (SD = 14) Male: 34% Origin: The Netherlands Design: cohort Quality: 9/16 (56.4%) |

Age, gender, educational level, SES | Functional disability | Side effects, medication type, dosing frequency | Health status, health profile, perceived health status, coping pattern, self-efficacy, QoL, social support | Multivariate | Target | NSAIDS (diclofenac and Naproxen) and DMARDS (SSZ and Methotrexate, MTX) |

| Measure | (MEMS) | |||||||

| Extent |

Taking non-compliance: 7–24% Incorrect dosing: 19–45% Timing non-compliance: 17–75% (Note: 2× medication class/4× medication type) |

|||||||

| de Thurah et al. (2010) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 126 Median age: 63.0 (range = 32–80) Male: 36% Origin: Denmark Design: cohort Quality: 10/16 (62.5%) |

Age, gender, educational level | Functional disability, disease duration, co-morbidities | Treatment dose (amount), concurrent medication | Treatment necessity, treatment concerns | Multivariate (prospective) | Target | MTX |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaires (CQ-R) | |||||||

| Extent |

23.5% (0 months) 23.1% (9 months) |

|||||||

| Garcia-Gonzalez et al. (2008) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 70 (RA) Mean age: 53.9 (SD = 12.7) Male: 33% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 10/16 (62.5%) |

Gender, ethnicity, educational level | Disease duration, disease activity | Side effects | General health status | Univariate | Target |

DMARDs and/or biologic agents (drug names not stated) Self-reported |

| Measure |

Questionnaire (CQ-R) Mean score 69.1 |

|||||||

| Extent | Reverse scored 0 (complete non-compliant-100 fully compliant) | |||||||

| Martinez-Santana et al. (2013) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 91 Median age: 58 (SD = 12.3) Male: 27.5% Origin: Spain Design: retrospective longitudinal Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Age, gender |

Medication type Previous treatment (previous exposure to aTNF drugs) |

Multivariate | Target | Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab | ||

| Measure | Probability of not experiencing change of treatment over a 1 year period | |||||||

| Extent | 30% | |||||||

| Muller et al. (2012) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 1199 Median age: 59.2 (SD = 13.1) Male: 17.3% Origin: Denmark Design: retrospective longitudinal Quality: 7/16 (44%) |

Age, gender, employment status, education, income, Residence status, language | Disease duration, co-morbidities, number of healthcare visits (to family doctor or rheumatologist), functional disability | Satisfaction with HCP, Information about RA, treatment scheme, Rheumatologist as source of RA information | Univariate | Target | RA medications | |

| Measure |

Self-report—Compliance: always took medication as prescribed Non-compliance: did not always take medication as prescribed, took less/more than prescribed, or mostly did not take the medication |

|||||||

| Extent |

Non-compliance: Less than prescribed—14.8% More often than prescribed—1.6% Ignore doctor’s recommendations: 1.7% |

|||||||

| Neame and Hammond (2005) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 344 Mean age: 49.5 years and over (mean age NR) Male: 33% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 10/16 (62.5%) |

Age, gender, SES, educational level | Disease duration, disease activity | Treatment necessity, treatment concerns, disease and treatment understanding | Univariate | Target | DMARDs (SSZ and MTX) | |

| Measure | Self-reported question from RAI | |||||||

| Extent | 8% | |||||||

| Park et al. (1999) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 120 Age: 56.07 (SD = 12.74) Male: 21% Origin: USA Design: longitudinal Quality: 14/16 (87.5%) |

Age | Anxiety, Depression, Cognitive factors (latent cognitive variable, practical barrier (busyness), control of negative affect, pain control, general control | Target | Not specified | |||

| Measure | MEMs | |||||||

| Extent | 62% omission errors in 1 month | |||||||

| Pascal-Ramos and Contreras-Yáñez (2013) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 149 Age: 38.5 (SD = 12.8) Male: 11% Origin: Mexico Design: cohort Quality: 9/14 (64.3%) |

Age, gender, residence status, occupation, marital status, insurance, education | Disease activity, co-morbidity, disease-specific autoantibodies (RF, ACCP), functional disability, follow-up duration | Medication type | Motivation for non-persistence, practical barriers—difficulty to find arthritis medicine and expense | Multivariate | Target | DMARDs |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (CQ) | |||||||

| Extent | NP: 66.4% | |||||||

| Pascual-Ramos et al. (2009) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 75 Age: 56.07 (SD = 12.74) Male: 16% Origin: Mexico Design: longitudinal cohort Quality: 7/14 (50.0%) |

Age, gender, years of education, SES, marital status | disease duration, disease activity, co-morbidity, functional disability | Medication type, previous treatment, treatment number | Univariate (prospective) | Target | DMARDs and corticosteroids | |

| Measure | Self-report (physician interview) | |||||||

| Extent | 57.3% | |||||||

| Quinlan et al. (2013) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 125 Age: 56.07 (SD = 12.74) Male: 17% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, education income | Disease duration, treatment provider | Total prescribed medication | Patient-provider relationship (involvement in medication decision making; confidence with contacting provider), health literacy | Bivariate and multivariate | Target | RA medication, NSAIDs, Biologic agents |

| Measure | MMAS | |||||||

| Extent | Mean adherence score (SD) = 0.84 (0.21) | |||||||

| Saad et al. (2009) |

Sample: Psoriatic arthritis N: 566 Age: 45.7 (SD = 11.1) Male: 47% Origin: UK Design: cohort Quality: 6/16 (37.5%) |

Age, gender | Disease duration, disease activity, co-morbidities | Medication type, other medications | Lifestyle (smoking), general health | Univariate and multivariate (prospective) | Target | Biologics (inFLiximab, etanercept, adalimumab) |

| Measure | HCP reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 24.5% | |||||||

| Spruill et al. (2014) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 56 Mean age: 51.5 (SD = 12.8) Male: 11% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/16 (44%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, Education, insurance type | Disease duration, symptoms (pain), disease activity, co-morbidities, functional disability | Medication type, dose | Treatment necessity, treatment concerns, self-efficacy | Univariate and multivariable | Target | Methotrexate, DMARD, biologics, corticosteroid, NSAID |

| Measure | MMAS | |||||||

| Extent | 37.5% | |||||||

| Treharne et al. (2004) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 85 Mean age: 58.9 (SD = 12.6) Male: 26% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, gender, marital status, number of children, children living at home, educational level, SES, spousal SES | Disease duration, disease activity, co-morbidities | Number of medications, medication type | HCP–patient relationship, social support, optimism, treatment necessity, treatment concerns | Univariate and multivariate | Target | DMARDs (MTX), NSAIDs, steroids |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaires (CQ-R) +2 items from the Reported Adherence to Medication (RAM) | |||||||

| Extent |

5.8% unintentional 9.4% intentional (assessed by the RAM) |

|||||||

| Tuncay et al. (2007) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 100 Mean age: 49.3 (SD = 11.8) Male: 15.1% Origin: Turkey Design: longitudinal Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Age, gender, insurance status | Disease duration, disease activity, symptoms (morning stiffness), functional disability | Treatment dose (number)—RA and overall | NR | Univariate | Target | DMARDs, NSAIDs, corticosteroids |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 11.6% | |||||||

| van den Bemt et al. (2009) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 228 Mean age: 56.2 (SD = 12.2) Male: 32.5% Origin: Netherlands Design: cross sectional Quality: 13/16 (81.3%) |

Age, sex, marital status, education level | Disease duration, functional disability | Number of medications, side effects | Treatment necessity, treatment concern, smoking, disease and treatment understanding, coping pattern | Univariate | Target | DMARDs |

| Measure |

Pharmacist interview. Self-reported questionnaire (CQ-R) and MARS |

|||||||

| Extent |

19% interview 33% CQR 60% MARS |

|||||||

| Viller et al. (1999) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 556 Mean age: 52.9 (SD = 12.2) Male: 14% Origin: France, Netherlands, Norway Design: cohort Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, gender, education level | Disease duration, symptoms (tenderness, inflammation), functional disability | Medication type, surgery/injections, side effects | Disease and treatment understanding, HCP–patient relationship, illness beliefs (severity, dependency, shame and adjustment) | Multivariate (prospective) | Target | NSAIDs, slow acting drug and corticosteroids |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 23.8% (18.9–44.5%) | |||||||

| Wainmann et al. (2013) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 107 Mean age: 52.9 (SD = 12.2) Male: 14% Origin: USA Design: prospective cohort Quality: 8/14(57%) |

Age, gender, education, marital status, ethnicity, insurance type, employment status, income, household members, language | Functional disability (DMARD), disease duration, disease activity (DMARD), symptoms (pain), hand radiographs | Medication type (Biologic agent use), Concomitant medication, pill burden (pills per day (prednisone) | Depression (DMARD), H-QoL social support, general health status | Multivariate | Target | DMARDs, prednisone |

| Measure | MEMs | |||||||

| Extent |

DMARDS- 36% Prednisone-30% |

|||||||

| Wong and Mulherin (2007) |

Sample: RA outpatients N: 68 Mean age: 55.8 (SD = 13) Male: 40% Origin: UK Design: longitudinal Quality: 8/16 (50.0%) |

Age | Symptoms (stiffness, pain, grip strength, swollen, tender joint count, disease activity, functional disability |

Beliefs about medication, HCP–patient relationship, anxiety, depression, social support (level/type) |

Multivariate (prospective) | Target | DMARDs (SSZ, MTX, Hydroxychloroquine, intramuscular gold) | |

| Measure | Patient-held records and case notes | |||||||

| Extent | 20% | |||||||

Factors assessed in relation to non-adherence were collated into four key categories: demographic; clinical; treatment and psychosocial

Factors found to be associated with treatment adherence highlighted in bold

ACCP anti–citrullinated protein antibodies, AS ankylosing spondylitis, aTNF anti-tumor necrosis factor, CQ choice questionnaire, CQ-R compliance questionnaire for rheumatology, DMARD disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, HCP health care professional, HMO health maintenance organization, H-QoL health-related quality of life, IQR interquartile range, MARS medication adherence report scale, MEMS medication event monitoring system, MMAS Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, MPR medication possession ratio, MTX methotrexate, NHI national health insurance, NR not recorded, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, PsA psoriatic arthritis, QoL quality of life, RA rheumatoid arthritis, RAI rheumatology, allergy and immunology, RAM reported adherence to medication, RCT randomized controlled trial, RF rheumatoid factor, SD standard deviation, SES socioeconomic status, SSZ sulphasalazine therapy, TNF tumor necrosis factor

Table 2.

Overview of included studies: IBD

| Authors and year | Sample characteristics, origin, and design | Factors measured | Analysis | Non-adherence: target, measure and extent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Clinical | Treatment | Psychosocial | |||||

| Bermejo et al. (2010) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 107 Mean age: 41.3 (SD = 11) Male: 40% Origin: Spain Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Gender, marital status | Disease type, disease duration, disease activity, admissions/surgical procedures | Medication type, dosing frequency | Disease understanding | Univariate | Target | Oral and topical |

| Measure | Self-report questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 69% (66% intentional/16% unintentional) | |||||||

| Bernal et al. (2006) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 214 Mean age: 40.3 (SD = 13.5) Male: 13% Origin: Spain Design: cross-sectional Quality: 4/16 (25.0%) |

Age, gender, employment status, educational level | Disease activity, disease duration, disease type, disease severity, disease related disability | Univariate | Target | Oral and topical | ||

| Measure | Self-report questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 43.5% (unintentional) 8% (intentional) | |||||||

| Billioud et al. (2011) |

Sample: CD outpatients N: 108 Median age: 35 (range 27–44) Male: 38% Origin: France Design: Cross-sectional Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, gender, marital status | Family history, disease type, disease duration, relapse history, age at diagnosis, previous investigations, past hospitalization | Concomitant treatment, medication dose | Lifestyle (smoking) | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Biologics (adalimumab) |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (reported missed or delayed injection) | |||||||

| Extent | 45.5% | |||||||

| Bokemeyer et al. (2007) |

Sample: CD outpatients N: 49 Median age: 38 (range 17–68) Male: 49.2 Origin: Germany Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender, employment status | Disease duration, disease activity, previous surgery | Medication dose, medication frequency, disease duration | Treatment concerns | Univariate | Target | Oral NSAIDs (AZA)/5 ASA |

| Measure | Thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) and questionnaire (VAS) | |||||||

| Extent | 9.2% (TPMT)and 7.1% (VAS) | |||||||

| Carter et al. (2012) |

Sample: CD population, medical and pharmacy claims data N: 448 Age: 42.6 (SD = 14.8) Male: 44% Origin: USA Design: retrospective observational cohort Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender, region | Outpatient visits, number of hospitalizations | Concomitant medication | Univariate | Target | Biologic (Infliximab) | |

| Measure | Medication possession ratio ≥80% | |||||||

| Extent | 23% | |||||||

| Červený et al. (2007) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 177 Mean age: 36.9 (SD NR) Male: 47.5% Origin: Poland Design: cross-sectional Quality: 5/16 (31.3%) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status | Disease type | Medication type | Lifestyle (smoking), | Univariate | Target | IBD medications (all) |

| Measure | Self-reported interview | |||||||

| Extent | 38.9% | |||||||

| Cerveny et al. (2007) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 396 Mean age: 38 (SD NR) Male: 51% Origin: Czech Republic Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status | Disease activity, disease type | Medication type | Lifestyle (smoking) | Univariate | Target | IBD medications (all) |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 42.6% (involuntary non-adherence) 32.5% (voluntary non-adherence) | |||||||

| D’Inca et al. (2008) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 267 Mean age: 41 (SD NR) Male: 51% Origin: Italy Design: cross-sectional Quality: 8/16 (50.0%) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status | Disease activity, disease duration, disease type, clinical status | Medication type, number of medications, dosing frequency, multiple daily doses | Forgetting, practical barriers (working day) | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Oral and rectal |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 39% | |||||||

| Ediger et al. (2007) |

Sample: IBD population N: 326 Mean age: 41 (SD = 14.06) Male: 40% Origin: Canada Design: cross-sectional Quality: 15/16 (93.8) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status | Disease type, disease activity, disease duration | Medication type, dosing frequency | Anxiety (HAQ), treatment concerns, treatment necessity, mastery, personality (agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism), practical barriers | Multivariate | Target | IBD medication not specified |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (MARS) | |||||||

| Extent |

35% (27% men; 37% women) |

|||||||

| Goodhand et al. (2013) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 144 Mean age: adults-40 (SD = 1.5); young adults-20 (0.2) Male: adults-62%, young adults-51% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 8/16(50%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, education level, SES | Co-morbidity, disease duration, Disease type (CD, UC, IBDU), disease activity, age at diagnosis, hospital visits (OPC, hospital admissions) | Daily dose frequency, pill Burden (no of pills per day), medication type, concomitant medications | Anxiety, depression, Lifestyle (smoking, alcohol) | Univar ate and Multivariate | Target | Thiopurine |

| Measure |

Self-reported questionnaire (Morisky Medication Adherence Scale—MMAS-8) 6-TGN levels |

|||||||

| Extent | 12% | |||||||

| Hovarth et al. (2012) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 592 CD Median age: 38 (15–81) Male: 46% Origin: Hungary Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/16 (44%) |

Gender, educational level | Disease type, disease activity, functional disability, CAM use, previous surgeries | Medication type (immunomodulator use) | H-QoL, need for psychologist, Lifestyle (smoking) | Univariate | Target | Aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biological therapy |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 13.4% | |||||||

| Horne et al. (2009) |

Sample: Members of the National Association for Colitis and Crohn’s disease (NACC) N: 1871 Mean age: 50.1 (SD = 15.9) Male: 37% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 12/16 (75.5%) |

Age, gender | Disease type, disease duration, GP visits, outpatient visits, inpatient visits | Treatment necessity, treatment concerns, attitudinal group | Multivariate | Target | IBD medications not specified | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (MARS) | |||||||

| Extent | 28% (unintentional) 32% (altered dose) 17% (stopped) | |||||||

| Kamperidis et al. (2012) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 189 Mean age: 38 (SD = 1.0) Male: 55% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 8/14 (57.1%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, SES | Disease type, disease activity | Concomitant medication | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Biologics | |

| Measure | Thiopurine in urine | |||||||

| Extent | 8% | |||||||

| Kane et al. (2001) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 94 Median age: 42.5 (range 18–79) Male: 51% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 6/14 (42.9%) |

Age, gender, marital stat us, employment status, insurance type | Disease activity, recent endoscopy, family history, length of remission | Concomitant medication | QOL | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Oral NSAID (5-ASA) |

| Measure | MED-TOTAL formula—refill and patient records | |||||||

| Extent | 60.0% | |||||||

| Kane (2006) |

Sample: CD outpatient database N: 274 Age: NR Male: 42.3% Origin: USA Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Age, gender (female), ethnicity, marital status, education, insurance type, area code |

Disease type, time since 1st infusion (>18 weeks) |

Concomitant medication | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Infliximab (biologic) | |

| Measure | Clinic appoint no show | |||||||

| Extent | 15.0% (at least one no show) | |||||||

| Kane et al. (2009) |

Sample: CD patients on national database N: 571 Mean age: 38.5 (15.0) Male: 45% Origin: USA Design: Longitudinal Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender | Co-morbidities, hospitalization, Outpatient visit, healthcare resource utilization and costs | Concomitant medications | NR | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Biologic (Infliximab) |

| Measure | Prescription refills | |||||||

| Extent | 34.3% | |||||||

| Kane et al. (2011) |

Sample: CD patients on national database N: 44,191 Mean age: NR Male: 37.3% Origin: USA Design: longitudinal Quality: 4/14 (28.6%) |

Medication type | NR | Univariate | Target | Oral NSAID (5-ASA, balsalazide + olsalazine) | ||

| Measure | Prescription refill rates | |||||||

| Extent | 87% (at 12 months) | |||||||

| Lachaine et al. (2013) |

Sample: UC patients: Prescription claims database N: 12,756 Mean age: 55.3 (SD = 17.8) Male: 43% Origin: Canada Design: retrospective longitudinal Quality: 7/12 (58%) |

Age, gender | Co-morbidities | Time of corticosteroids use (previous, current) | Multivariate | Target | 5-ASA | |

| Measure | MPR (Medication Possession Ratio) | |||||||

| Extent |

80% + adherence at 12 months: 27.7% Persistence at 12 months: 45.5% |

|||||||

| Lakatos (2009) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 655 Mean age: 44.9 (SD = 15.3) Male: 46% Origin: Hungary Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/116 (56.3%) |

Educational level (CD only) | Disease duration, previous surgery (CD only), last follow-up visit (CD only) | Concomitant medications | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Oral and biologic | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent |

CD: 20.9% UC: 20.6% |

|||||||

| Linn et al. (2013) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 68 Mean age: 40.5 (SD = 14.9) Male: 38% Origin: The Netherlands Design: prospective Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, education | Medication type | Recall of medical information | Multivariate | Target |

Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, Infliximab Methotrexate, 6-thioguanine, or Adalimumab |

|

| Measure | Self-reported question | |||||||

| Extent | Mean adherence (SD) = 9.1 (1.2) (range 1–10) | |||||||

| Mantzaris et al. (2007) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 28 Mean age: 34.6 (SD = 9.2) Male: 46.6% Origin: Greece Design: prospective Quality: 8/16 (50.0%) |

Age, gender, marital status | Family history, disease location, disease duration, prior surgery, disease activity | Concomitant medications | Lifestyle (smoking), QOL | Univariate | Target | Oral (azathioprine) |

| Measure | Self-reported number daily pills | |||||||

| Extent | 74.3% | |||||||

| Mitra et al. (2012) |

Sample: UC patients from insurance claims database N: 1693 Mean age: 42.3 (SD = 12.8) Male: 50.4% Origin: US Design: retrospective longitudinal Quality: 8/12 (66.7%) |

Age, gender, geographic region, health plan type, insurance type | Healthcare costs, healthcare utilization, co-morbidity | Multivariate | Target | 5-ASA | ||

| Measure | MPR | |||||||

| Extent | 72% | |||||||

| Moradkhani et al. (2011) |

Sample: convenience sample from IBD support group forum N: 111 Mean age: 31 (SD = 8.5) Male: 22.5% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, SES, employment, education, marital status | Disease type, disease activity (pt rating and physician), disease duration, setting of IBD care | Disease understanding, | Univariate | Target | IBD medications not specified | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (Morisky) | |||||||

| Extent | Mean score 1.68 (SD = 1.43) | |||||||

| Moshkovska et al. (2009) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 169 Mean age: 49 (SD NR) Male: 51% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, SES | Disease duration | Medication type, treatment center | Treatment necessity, treatment concerns, satisfaction with information about medicines (SIMS) [HCP–patient relationship] | Univariate and multivariate | Target | NSAID (5-ASA) |

| Measure | Urine and self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 40% (urine), 34% (self-report) | |||||||

| Nahon et al. (2011) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 1663 Mean age: 31 (SD = 8.5) Male: 22.5% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/16 (43.8%) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, SES | Disease type, disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, surgery anoperineal location, family history | Medication type, complicated dosing regimen, number of tablets, lack of physician info, impact of schedule on daily life | Lifestyle (smoking), anxiety, mood, depression, feeling well, patient association member | Univariate and multivariate | Target | IBD medications not specified |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (visual analog scale) | |||||||

| Extent | 10.4% | |||||||

| Nahon et al. (2012) |

Sample: IBD patients N: 1663 Mean age: 43.6 (SD = 15.4) Male: 26% Origin: France Design: cross-sectional Quality: 7/15 (46.7%) |

Anxiety, depression | Univariate and multivariate | Target | Immunosuppressant, aTNF-a, 5-ASA, corticosteroids | |||

| Measure | Self-reported (VAS) | |||||||

| Extent | 10% | |||||||

| Nguyen et al. (2009) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 235 Mean age: 42.2 (SD = 14.2) Male: 43% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 10/16 (62.5%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, marital status, employment status, health insurance | Disease severity, disease type, attained age | Concomitant medication | HCP–patient relationship, QOL |

Univariate, multivariate |

Target | IBD medications not specified |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 35.0% | |||||||

| Nigro et al. (2001) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 85 Mean age: Not stated Male: 45% Origin: Italy Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

NR | Disease duration, disease severity | Psychiatric disorder [emotional well-being] | Univariate and multivariate | Target | IBD medications not specified | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 7.0% non-compliant; 10.5% partial (details not provided) | |||||||

| Robinson et al. (2013) |

Sample: IBD patients from drug records N: 568 Mean age: 56 (SD = NR) Male: 51% Origin: UK Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 8/12 (66.7%) |

Relapse history | Medication type, treatment switches | Target | Mesalazine formulations | |||

| Measure | MPR | |||||||

| Extent | 61% | |||||||

| San Román et al. (2005) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 40 Mean age: 39.4 (SD = NR) Male: 50% Origin: Spain Design: cross-sectional Quality: 4/16 (25.0%) |

Age, gender, education level, SES | Disease type disease duration, symptom duration, disease activity | Medication type, medication dose, treatment schedule | QOL, depression, HCP–patient relationship (discordance and trust), treatment understanding | Univariate | Target | Topical, oral, biologics (infliximab, adalimumab) |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 72% | |||||||

| Selinger et al. (2013) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 356 Mean age: Australia-47 (SD = NR), UK-46.8 (SD = NR) Male: Australia 45%, UK-38% Origin: Australia and UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Gender, patient source (hospital clinic, office), marital status, employment, ethnicity, educational level, income | Disease type, disease duration, hospital admissions | Concomitant medication, medication type | Anxiety, depression, QoL, disease knowledge, necessity beliefs, treatment concerns, support group membership | Multivariate | Target | 5-ASA, thiopurines, biological agent |

| Measure | MARS | |||||||

| Extent | 28.7% | |||||||

| Selinger et al. (2014) |

Sample: IBD patients from claims database N: 12,592 Mean age: 49 (SD = NR) Male: 42% Origin: US Design: longitudinal Quality: 7/12 (58.3%) |

Age, gender | Medication type | Univariate | Target | 5-ASA | ||

| Measure | No prescription fill for at least 3 months | |||||||

| Extent | Sulfasalazine 5-ASA: 22.3% (12 m), 11.9% (24 m) Non-sulfasalazine 5-ASA: 28.5% (12 m), 16.2% (24 m) | |||||||

| Sewitch et al. (2003) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 153 Mean age: 37 (SD = 15.1) Male: 43% Origin: Canada Design: prospective Quality: 13/16 (81.3%) |

Age, gender, educational level, income, marital status, language | Disease type, disease duration, new patient status, disease activity, physician duration, length of visit, further test recommendation, appointment rescheduling, consulting other HCP | Medication type | HCP–patient relationship, psychological distress, treatment efficacy, social support, [perceived stress, stressful events—emotional well-being], lifestyle (smoking) | Multivariate + sensitivity analysis | Target | IBD medications (all) |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent: | 41.2% | |||||||

| Shale and Riley (2003) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 98 Median age: 49 (range 17−85) Male: 51% Origin: UK Design: Cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status | Disease type, disease severity, disease duration, disease activity, relapse frequency | Medication dose, medication frequency, concomitant medications | Treatment efficacy, QOL, HCP–patient relationship, depression, anxiety, membership of patient group | Univariate and multivariate | Target | NSAIDs (Asacol:5-ASA) |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire, urinary ASA | |||||||

| Extent | Self-report 48%/urinary ASA 12% | |||||||

| Taft et al. (2009) |

Sample: Self-reported IBD N: 211 Mean age: 46.5 (SD NR) Male: 23% Origin: USA Design: cross-sectional Quality: 11/16 (68.8%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, marital status | Disease duration, flare (frequency, duration and severity), remission of symptoms, previous surgery | Stigma | Univariate and multivariate | Target | IBD medications not specified | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire (MTBS) | |||||||

| Extent |

Mean score (SD) CD: 0.98 (1.19), UC: 1.02 (1.22) |

|||||||

| Waters et al. (2005) |

Sample: IBD outpatients N: 89 Age: 45 (SD = 13.5) Male: 57% Origin: USA Design: RCT Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Age, gender (female), internet use (higher use), Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Membership (not a member) | Frequency of physician visits | Univariate | Target | IBD meds (all) | ||

| Measure | Patient diary | |||||||

| Extent | 54% | |||||||

| Yen et al. (2012) |

Sample: IBD patients from claims database N: 5644 Mean age: 48.3 (SD = 15.4) Male: 47% Origin: Australia Design: longitudinal Quality: 8/12 (66.7%) |

Age, gender, health plan type (persistence only), insurance type, geographical region (adherence only) | Never receiving specialist care, co-morbidities (persistence only) | Medication type, medication administration route (adherence only), previous treatment (adherence only), no switch from index drug (adherence) | Multivariate | Target | 5-ASA medications | |

| Measure |

Persistence: time to discontinuation Adherence: MPR |

|||||||

| Extent |

Non-adherence: 79% Discontinuation of index drug (over 12 month period): 68.7% |

|||||||

Factors found to be associated with treatment adherence highlighted in bold

5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid, 6-TGN 6-thioguanine nucleotide, IBDU inflammatory bowel disease unclassified, ASA Acetylsalicylic acid, aTNF anti-tumor necrosis factor, AZA azathioprine, CAM complementary and alternative medicine, CD Crohn’s disease, GP general practitioner, HAQ health assessment questionnaire, HCP health care professional, H-QoL health-related quality of life, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, MARS medication adherence report scale, MMAS Morisky medication adherence scale, MPR medication possession ratio, MTBS medication taking behavior scale, NR not recorded, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, OPC outpatient clinic, QOL quality of Life, SD standard deviation, SES socioeconomic status, SIMS satisfaction with information about medicines, TPMT thiopurine S-methyltransferase, UC Ulcerative colitis, VAS visual analog scale

Table 3.

Overview of included studies: Psoriasis

| Authors and Year | Sample characteristics, origin, and design | Factors measured | Analysis | Non-adherence: target, measure and extent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Clinical | Treatment | Psychosocial | |||||

| Altobelli et al. (2012) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 1689 Age: 48.6 (SD = 15.0) men; 47.4 (SD = 15.5) women Male: 56.8% Origin: Italy Design: cross-sectional Quality: 9/16 (56.3%) |

Gender, age, education, marital status, employment status | Psoriasis type (disease type), age at onset, disease-duration, affected body sites and body surface area affected | Univariate | Target | All modalities (topical, systemic and alternative treatments) | ||

| Measure | Questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 54.1% | |||||||

| Bhosle et al. (2006) |

Sample: Psoriasis patients on Medicaid programme in North Carolina N: 186 Median age: 41.0 (SD = 11.44) Male: 41.4% Origin: USA Design: longitudinal Cohort Quality: 9/13 (69.2%) |

Age, gender, ethnicity | Co-morbidity | medication type, combination therapy | Multivariate (prospective) + sensitivity analysis | Target | Biologics (alefacept, efalizumab etanercept, 80% on combination therapy) | |

| Measure | Prescription refill records (MPR) | |||||||

| Extent |

44.0% overall 34.0% biologics |

|||||||

| Chan et al. (2013) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 106 Mean age: NR Male: 50% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 8/16 (50.0%) |

Age, gender, marital status, employment status, educational level | Disease severity (topical therapy only) | Number of treatment types, medication type | Lifestyle (smoking alcohol use), treatment efficacy, treatment satisfaction, practical barriers (fed up, too busy lotions too messy), QoL (topical therapy only) | Univariate | Target | Topical, oral systemic, phototherapy, biologics |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 14.2% | |||||||

| Chastek et al. (2013) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 827 Age: 43 (SD = 12) Male: 52–56% Origin: USA Design: retrospective Pharmacy database Quality: 6/12 (50.0%) |

Medication type | Univariate | Target | Biologics (Etanercept and adalimumab) | |||

| Measure | Persistence over 12 months (Medication refills) | |||||||

| Extent | 59.6% Etanercept, 57.6% Adalimumab | |||||||

| Clemmensen et al. (2011) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 71 Mean age: 43.1 (SD = 13.0) Male: 51% Origin: Denmark Design: Cohort Quality: 5/12 (41.7%) |

Medication type | Multivariate (prospective) | Target | Biologics (ustekinumab, adalimumab, etanercept) | |||

| Measure | Patient medical records (persistence) | |||||||

| Extent | 4.2% (321 days) | |||||||

| Esposito et al. (2013) |

Sample: Psoriasis patients from medical/digital databases N: 650 Mean age: 49.0 (SD = 13.1) Male: 66% Origin: Italy Design: retrospective cohort Quality: 7/12 (58.3%) |

Age, gender | Disease severity (Psoriasis area and severity index) | Medication type | Univariate | Target | aTNF (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab) | |

| Measure | Patient medical records (persistence) | |||||||

| Extent | 27.4% at 2 years | |||||||

| Gniadecki et al. (2011) |

Sample: psoriasis patients N: 747 Mean age: 45.0 (SD NR) Male: 67% Origin: Denmark Design: Cohort Quality: 6/12 (50.0%) |

Age, gender | Disease duration, presence of psoriatic arthritis, Co-morbidity | Concomitant medication, prior treatment (prior use of anti-TNF), medication type | QoL | Multivariate | Target | Biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept) |

| Measure | Patient medical records (persistence) | |||||||

| Extent |

32.3% overall Infliximab 25.58% Adalimumab 32.0% Etanercept 36.2% |

|||||||

| Gokdemir et al. (2008) |

Sample: Psoriasis patients N: 109 Mean age: 40.1 (SD = 15.2) Male: 44% Origin: Turkey Design: cross-sectional Quality: 5/14 (35.7%) |

Gender, marital status, education level, employment status, family history (note demographic factors not significant in multivariate analysis) | Disease severity | Medication type | Lifestyle (smoking), QoL, satisfaction with treatment | Univariate and multivariate (prospective) | Target | Topical, oral, combined and phototherapy |

| Measure | Number or weight of prescribed doses taken by the patient/number or weight of doses prescribed for the patient × 100% | |||||||

| Extent | Not given | |||||||

| Richards et al. (1999) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 120 Mean age: 49.0 (SD = 16.0) Male: 54% Origin: UK Design: cross-sectional Quality: 6/16 (37.5%) |

Age, gender | Age at onset, disease duration, disease severity | General well-being, impact on life, interfered with life | Univariate | Target | Topical, systemic, combination and phototherapy | |

| Measure | Self-reported questionnaire | |||||||

| Extent | 39.0% | |||||||

| Umezawa et al. (2013) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 127 Mean age: I:A:U = 52.1:50.1:62.3 (SD = 11.4:10.7:12.3) Male: 72% Origin: Japan Design: longitudinal Quality: 5/14 (35.7%) |

Medication type | Univariate and Multivariate | Target | Infliximab, adalimumab and ustekinumab | |||

| Measure | Drug survival rate (at 12 month follow-up) | |||||||

| Extent |

Proportion discontinuing (less than a year): Infliximab—26.3% Adalimumab—20.3% Ustekinumab—3.3% |

|||||||

| Zaghloul and Goodfield (2004) |

Sample: Psoriasis outpatients N: 201 Mean age: 45.1 (SD = 10.1) Male: NR Origin: UK Design: longitudinal Quality: 4/16 (25.0%) |

Age, gender, marital status, employment status, medication payment | Disease severity, lesion location, Number of lesions | Medication type, Medication frequency, previous treatment (naïve to treatment), side effects | QoL, lifestyle (smoking, alcohol consumption) | Univariate | Target | Topical and oral |

| Measure |

Number or weight of prescribed doses taken by the patient/number or weight of doses prescribed for the patient × 100% Self-report interview |

|||||||

| Extent |

Number of doses or weight: 60.6% Self-report: 92.0% |

|||||||

Factors found to be associated with treatment adherence highlighted in bold

aTNF anti-tumor necrosis factor, MPR medication possession ratio, NR not recorded, QoL quality of life, SD standard deviation

The sample size of the studies varied considerably, ranging from 28 to 12,750 participants. The vast majority of studies (90.4%) were based on samples from Europe (n = 37, 51%) or North America (n = 30, 41%). Participants were derived from outpatient clinics in the majority of samples. In RC, this was 76.9% (n = 20), in IBD (n = 25, 69.4%) and in PS (n = 8, 72.7%). One sample in RC [23] was recruited in a clinical trial and two samples in IBD [69, 79] were convenience samples recruited online through social media or IBD forums. The remaining samples were established cohorts drawn from medical or pharmacy databases.

The proportion of longitudinal studies (including retrospective cohorts) was 57.8% (n = 15) in RC, 36.1% (n = 13) in IBD, and 72.7% (n = 8) in PS. While a substantial proportion of studies had a longitudinal design, factors were most often examined as concurrent associates of adherence and not as prospective predictors. Thus, in the current review all factors are considered as potential associates of adherence.

A large proportion of studies (57.5%) used self-report measures to assess adherence. In RC, the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) was used to measure non-adherence in three studies [28, 34, 44], others used pill counts and pharmacy refill data [22, 23, 27] or plasma analysis [21]. Five studies had a measure of medication persistence (i.e., continuation with a medication) as the adherence outcome, obtained via HCP report [36, 38] or patient records/case notes [25, 26, 45]. In IBD, three studies combined self-report measurement with a biochemical measure [39, 53, 59]. One study assessed adherence using a biological measure only [58] and another via infusion appointment attendance [12]. The remaining five studies used a proxy measure of adherence via prescription refill data [41, 49–51, 76]. In PS, two studies assessed adherence using a proxy measure from prescription refill data [83, 85]. A further three studies had a measure of medication persistence as the adherence outcome obtained from patient medical records [86–88]. Two studies assessed adherence with respect to unused treatment medication ascertained via pill counts weight [89, 92].

Quality of Included Studies

The proportion of quality criteria met by each study varied widely across the three clinical areas, ranging between 31% and 87.5% in RC, 25% and 93.8% in IBD, and 25% and 58.3% in PS. The included studies in RC typically met the highest proportion of quality criteria, whereas those in PS met the least. Quality criteria most commonly not met related to details of the study required to enable an assessment of bias. A number of studies did not report details of eligibility criteria (n = 15, 20.5%) or the number of participants not consenting to participate in the study (n = 42, 57.5%), so it was not possible to make an assessment of biases due to participant selection. Similarly, failure to report how missing data were treated (n = 65, 89%) and control for confounders (n = 35; 52%) was common preventing an assessment of the strength of the associations found. The majority of studies did not report power calculations (n = 56, 77%) to estimate their sample sizes and as such it was difficult to assess whether studies were adequately powered to detect associations. However, several studies had very small sample sizes that were unlikely to result in adequate power for the statistics applied.

Overview of Findings

Adherence rates varied considerably in all clinical areas and ranged between 7% and 75% in RC, 4% and 72% in IBD, and 8% and 87% in PS. Evidence of an association of rates according to the adherence measure type (e.g., self-report, MEMs, biochemical, medication possession ratio) was not found. Factors assessed in relation to non-adherence were collated into four key categories: demographic; clinical; treatment; and psychosocial. All the factors explored across two or more chronic conditions, or in one condition and in a minimum of two studies with consistent results are presented in Table 4. The table summarizes the frequency of studies examining these factors and proportion of studies to find a statistically significant association.

Table 4.

Number of studies to examine factor and to find an association with non-adherence according to individual condition and overall

| Factors | RC (N = 26) | IBD (N = 36) | Psoriasis (N = 11) | Overall (N = 73) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies analyzing factor | Number of studies in finding an association (p < 0.05) | Number of studies analyzing factor | Number of studies finding association | Number of studies analyzing factor | Number of studies finding association (p < 0.05) | Nos. of studies analyzing factor | Nos. of studies finding association | Proportion of studies finding an association % | ||

| Demographic | Age | 22 | 8 | 29 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 58 | 20 | 34.5 |

| Gender | 20 | 5 | 31 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 59 | 15 | 25.4 | |

| Marital status | 6 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 25 | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Education level | 17 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 39 | 6 | 15.4 | |

| Socioeconomic status | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 10.0 | |

| Employment status | 3 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 19 | 5 | 26.3 | |

| Ethnicity | 5 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 4 | 30.8 | |

| Geographical location | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 75.0 | |

| Income | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 33.3 | |

| Insurance type | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 16.7 | |

| Clinical | Disease duration | 15 | 2 | 19 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 37 | 8 | 21.6 |

| Disease activity | 12 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 7 | 25.0 | |

| Disease severity | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 50.0 | |

| Co-morbidity | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 43.8 | |

| Functional disability | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 12.5 | |

| Family history | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Symptoms | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | |

| Relapse history | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Lesion location | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 100 | |

| Treatment | Medication Type | 14 | 4 | 17 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 40 | 21 | 52.5 |

| Dose | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 28.6 | |

| Dosing frequency | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 71.4 | |

| Previous treatment | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | |

| Side effects | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 40.0 | |

| Concomitant medications | 2 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| Psychosocial | Treatment necessity | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 55.6 |

| Treatment concerns | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 70.0 | |

| Emotional well-being (anxiety or depression) | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 66.7 | |

| HCP–patient relationship | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 77.8 | |

| Treatment efficacy | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 50.0 | |

| Treatment self-efficacy | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 100 | |

| Practical barriers | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| Support group/society member, internet users (IBD) | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 28.6 | |

| General health status | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Quality of life | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 45.5 | |

| Disease or treatment understanding | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 40.0 | |

| Lifestyle (smoking) | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 4 | 26.7 | |

| Illness beliefs | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

RC rheumatologic conditions, IBD inflammatory bowel disease

Demographic Factors

Age and gender were the most commonly examined factors (79.5% and 80.8%) in relation to adherence across conditions. The majority of studies to examine them (n = 38, 65.5% and n = 44, 74.6%, respectively) found no association with adherence and, where these were found, the findings were not consistent. The exception was for IBD where older age was found to be associated with greater likelihood of adherence in all studies to find an association (n = 11). However, an association was found in only a minority of the IBD studies; the majority (i.e., 18 out of 29) found age not to be associated with adherence. Marital status, education level, socioeconomic status, employment status, income, insurance type, geographical location and ethnicity were not consistently associated with non-adherence across diseases.

Clinical Factors

Clinical factors were the second most commonly examined (see Table 4). Disease duration and disease activity were the two clinical factors examined most frequently (n = 37 and n = 28). However, only a small proportion of these studies (21.6% and 25%) found an association with adherence, and where associations were found, the relationship was not found to be consistent. In some cases, the relationship between disease duration and activity was positively associated with adherence, while in others there was a negative association. Disease severity and lesion location, although only examined in a minority of studies (n = 10 and n = 2), reported the most consistent associations. In the PS studies, disease severity was the most commonly examined clinical factor in relation to adherence (45.5%). An association with adherence was found in three of these studies (60%), in which patients with lower disease severity were more likely to be non-adherent to their PS treatment than those with greater disease severity [84, 90, 92]. Only two of the five IBD studies (40%) to examine this reported an association between disease severity and adherence and the direction of this association conflicted. None of the included RC studies examined disease severity.

Location of psoriatic lesions was examined in two of the PS studies (18%). Non-adherence was found to be more likely among patients with facial lesions compared to those with lesions restricted to the rest of the body or with increasing number of lesion sites [92] and among those with greater body surface area of lesions [72]. Further details about these studies are available in the Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Treatment Factors

Medication type, dosing frequency, and previous treatment showed the most frequent association with adherence in the treatment category. Medication type was the most commonly explored treatment factor, which was assessed in 40 studies (54.8%) with an association to non-adherence reported in over half of these studies (52.5%).

In RC, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were found to be associated with lower adherence levels than disease-modifying medications [conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs)] in one study [28]. Another study found an association only for patients on steroids with these more likely to be adherent than those patients on NSAIDs or csDMARDs [40], although no association with corticosteroid use was observed in the other study examining this [36]. Among anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) treatments, significantly higher discontinuation rates and lower adherence levels were found for the biologic infliximab compared to the biologic etanercept and adalimumab [31, 38].

In IBD, greater adherence was associated with patients receiving anti-TNF (versus Prednisolone, Budesonide, exclusive enteral nutrition and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASAs) [58], immunomodulator (versus 5-ASA) [46, 54, 56], and steroid treatments compared to those who prescribed other medications (including 5-ASAs, immunosuppressants and antibiotics) [74]. In another study, non-adherence was reported to be more frequent in treatment with 5-ASAs compared to treatment with thiopurines and biological therapy [75]. Patients on oral treatment were more likely to be adherent compared to those on topical and enema treatments in another study [53].

Persistence rates were significantly higher for patients taking non-sulfasalazine 5-ASA compared to those taking sulfasalazine 5-ASA in one study [76], whereas in another study persistence was higher for those prescribed a multi-matrix system mesalamine 5-ASA compared to those prescribed balsalazide, mesalamine delayed release or sulfasalazine 5-ASAs [81]. In PS, six studies looked for associations according to biological DMARD, with higher persistence to adalimumab or etanercept compared to infliximab in one study [88], higher persistence to etanercept compared to both adalimumab and infliximab in another study [87] and higher persistence to ustekinumab compared with other anti-TNFs found in two studies [86, 91]. The other two studies found no difference in levels of adherence between adalimumab and etanercept [85] or between alefacept, efalizumab or etanercept [83].

The number of doses taken daily was explored in seven studies across the diseases, of which the majority found an association (71.4%, n = 5). While the dosing frequencies examined varied between studies, associations were consistent, in that a greater likelihood of adherence to treatment was found with less frequent dosing.

Previous treatment was explored in five studies, four of which found an association with adherence (80%). Three of these studies reported that previous exposure to the same drug or similar type of treatment increased the likelihood of non-adherence/early discontinuation [31, 88, 92]. This may be due to confounding factors such as lack of efficacy or acquired resistance to the drug class. The remaining study, reported that not having used rectal 5-ASA or immunosuppressive/biologic agents, was associated with the risk of non-persistence and non-adherence to 5-ASAs [81].

Psychosocial Factors

Thirteen psychosocial factors were examined in relation to adherence (see Table 4). Psychosocial factors were most commonly examined in the studies of IBD, followed by RC and were rarely examined in studies of PS. Treatment beliefs (i.e., necessity, concerns and efficacy), emotional well-being (depression and anxiety), HCP–patient relationship, treatment self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one’s ability to follow treatment) and practical barriers (e.g., frequent traveling, forgetfulness, etc.) were found to be associated with non-adherence in at least 50% of the studies to examine these. Non-adherence was found to be associated with doubts about treatment necessity in 55.6% of the studies to examine this [29, 40, 57, 68, 75]. Similarly, concerns about side effects and low perception of treatment efficacy were found to be associated with non-adherence in 70% and 50% of studies to examine this, respectively [29, 33, 39, 40, 57, 68, 78, 84]. Four of the ten studies in RC and IBD to examine depression found a consistent association with non-adherence, with greater non-adherence reported amongst patients with depression or depressive symptoms. For anxiety, while over a third of the studies to examine this (n = 3, 37.5%) found an association with non-adherence, the direction of association was inconsistent. No studies assessed depression or anxiety in patients with PS. Practical barriers (e.g., frequent traveling, forgetfulness, etc.) were explored in six studies, and five of these found non-adherence to be more likely when practical barriers to taking treatment were perceived to be present. There was also some evidence that low levels of trust and satisfaction in the HCP–patient relationship may increase treatment non-adherence, with an association reported in 77.8% of the studies to examine this [32, 37, 40, 43, 71, 74, 77]. This factor was not examined in any of the PS studies. Lower treatment self-efficacy was significantly and consistently associated with poorer medication adherence in all three studies of RC [23, 28, 39]. This factor was not examined in any of the IBD or PS studies.

Discussion

This is the first review to systematically examine factors associated with non-adherence to treatment specifically for patients with selected IMIDs across three clinical areas. Demographic factors were the most commonly examined in relation to non-adherence followed by clinical and treatment factors. Psychosocial factors were examined in a minority of studies in RC and IBD and rarely examined in the PS studies. However, several consistent associations with adherence were observed for psychosocial factors that appear independent of the therapeutic area assessed.

While examined most commonly, none of the demographic or clinical factors were found to be consistently associated with non-adherence. Despite the general beliefs that some demographic factors are associated with non-adherence, this finding is in line with the other systematic literature reviews, where there is no consistent relationship between demographic characteristics and adherence in patients with chronic conditions [2–4]. Of the demographic factors, there was some evidence of an association between older age and adherence to IBD treatments; however, further studies are necessary to fully determine this.

With the clinical factors, there was some evidence that treatment non-adherence may be more likely among patients with PS with greater number/body surface area of lesions and among those with facial lesions in both studies to examine them. While the association of greater non-adherence with increased lesion coverage may appear counterintuitive, the visibility of psoriatic lesions to others well-being is put forward as a main stigmatizing factor from the patients’ perspective which may have a significant impact on perceptions of body image and well-being [93], thus it is possible that the observed association is mediated by psychosocial factors such as anxiety or depression, the effects of which are discussed below. However, it is important to note the observed association is based on only two studies rated to be of medium to low quality.

Some evidence of an association was also found with the treatment factors including frequency of dosing and medication type. Due to wide heterogeneity in the medication types assessed, and scarce comparison studies among drug classes and between oral and injectable medications, it is not possible to draw conclusions as to which types of medication are associated with greater non-adherence. Consistent with some earlier studies [94, 95], less frequent dosing was associated with increased adherence, which may reflect the lower demand on memory and planning for the patient. However, it was not possible to assess whether there was a dosing frequency above which the likelihood of treatment non-adherence is increased, again due to wide heterogeneity in dosing frequencies assessed.

Psychosocial factors were only explored in a minority of studies. Despite heterogeneity in measures used, several consistent associations were observed. In particular, the current review found evidence that lower perceptions of treatment necessity [29, 40, 57, 68, 75] and of treatment efficacy [78, 84], greater treatment concern [39, 78, 84] and higher HCP–patient discordance [32, 37, 40, 43, 71] were associated with greater likelihood of non-adherence. Similar associations have been observed for necessity and concern beliefs about medication and the HCP–patient relationship in previous reviews of adherence in IBD and RA specifically [3, 13, 15, 17], as well as in a systematic review across multiple conditions [96]. This suggests that addressing treatment concerns, increasing understanding of treatment necessity, and enhancing HCP–patient communication may be paramount to facilitate treatment adherence, irrespective of the type of IMID.

Evidence of an association of poorer emotional well-being, particularly depression, with non-adherence was found in the current review. Associations between anxiety and non-adherence on the other hand were less consistent, indicating that if an association exists, this may be weaker. These findings are consistent with those of a systematic review of studies of patients across a range of chronic conditions [97]. Both reviews suggest that depression but not anxiety may be a risk factor for treatment non-adherence in IMIDs, as well as chronic conditions more generally. This finding is of high importance, as depression is a potentially modifiable factor if diagnosed and treated appropriately, thus reducing the likelihood of poor adherence. It also raises an important question about the nature of the process in this effect. For example, depression might have effects on memory and planning ability, as well as on beliefs about treatment and efficacy [97, 98].

Treatment self-efficacy may also be an important factor for treatment adherence. Thus, patients with stronger beliefs in their ability to follow treatment were found to be more likely to adhere than those with comparatively weaker self-efficacy beliefs. Although, this was only examined in studies of RC, previous systematic reviews have found treatment self-efficacy to be closely related to adherence in a number of different chronic conditions [96]. However, to enable firm conclusions to be drawn, further research is needed to investigate these factors among patients specifically with PS and IBD.

Evidence of an impact of practical barriers in treatment adherence was also found in the current review. The category of practical barriers is broad and can encompass many different types. The application of some topical creams in PS, for example, presents physical and possibly social barriers to administering treatment. Frequent traveling, busy lifestyles or forgetfulness may present time- and routine-related barriers. While these barriers on the surface may appear to be unintentional drivers of non-adherence, recent research has shown that patient perceptions of unintentional factors can be predicted by medication beliefs (intentional non-adherence factors [99]). This suggests that practical barriers may reflect in part reduced motivation to take treatment, and, as such, addressing treatment beliefs would also be necessary to overcome them. For this reason, practical barriers are incorporated into the broader category of psychosocial risk factors.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research