Abstract

While the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) is best known for its role in regulating serum cholesterol, LDLR is expressed in brain, suggesting that it may play a role in CNS function as well. Here, using mice with a null mutation in LDLR (LDLR-/-), we investigated whether the absence of LDLR affects a series of behavioral functions. We also utilized the fact that plasma cholesterol levels can be regulated in LDLR-/- mice by manipulating dietary cholesterol to investigate whether elevated plasma cholesterol might independently affect behavioral performance. LDLR-/- mice showed no major deficits in general sensory or motor function. However, LDLR-/- mice exhibited increased locomotor activity in an open field test without evidence of altered anxiety in either an open field or a light/dark emergence test. By contrast, modulating dietary cholesterol produced only isolated effects. While both C57BL/6J and LDLR-/- mice fed a high cholesterol diet showed increased anxiety in a light/dark task, and LDLR-/- mice fed a high cholesterol diet exhibited longer target latencies in the probe trial of the Morris water maze, no other findings supported a general effect of cholesterol on anxiety or spatial memory. Collectively these studies suggest that while LDLR-/- mice exhibit no major developmental defects, LDLR nevertheless plays a significant role in modulating locomotor behavior in the adult.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, acoustic startle, cholesterol, light/dark preference, low-density lipoprotein receptor, Morris water maze, null mutation, open field

1. Introduction

The low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) plays a critical role in regulating serum cholesterol by removing cholesterol-rich lipoprotein particles from blood (reviewed in [18]). It is highly conserved evolutionarily and was the first member identified in a larger family of transmembrane proteins that regulate cholesterol transport by binding apolipoproteins such as ApoE as well as mediating signaling through a variety of secreted ligands including reelin [14].

LDLR is most highly expressed in liver [4]. Other tissues have generally smaller numbers of LDLRs but may increase receptor production when local demand for cholesterol increases. Low but detectable levels of LDLR RNA are found in brain [15]. As judged by in situ hybridization, LDLR expression is widely distributed in brain [30] and likely found in neurons, astrocytes, and endothelial cells [9,10,15,22,25,30]. However, LDLR null mutant mice (LDLR-/-) show no obvious anatomic defects in brain and thus LDLR has been considered to be of lesser importance in brain development and function than other family members such as LRP, ApoER2, or VLDLR [13]. Yet LDLR-/- mice have been reported to exhibit defects in spatial memory [23]. In addition, LDLR is upregulated in brain following ischemic injury [19], and brain ApoE levels are elevated in LDLR-/- mice [11,12], suggesting that LDLR may be an important ApoE receptor in brain.

The LDLR receptor was first identified because of its association with familial hypercholesterolemia [8]. Interestingly, hypercholesterolemia itself has been suggested to be an independent risk factor for brain disease. In particular, elevated serum cholesterol has been suggested to increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD) [3,5,21,28]. Why hypercholesterolemia might promote AD is not understood. One possibility is that hypercholesterolemia increases ischemic vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease is commonly found in association with AD [29]. Recent studies have also found a correlation between the severity of coronary artery disease and the degree of AD-neuropathology [1]. Besides influencing co-morbid vascular disease, both in vitro and in vivo studies also suggest that high cholesterol increases amyloidogenic processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) towards production of the Abeta (Aβ) peptide which deposits in senile plaques [32].

Here, using LDLR-/- mice, we investigated whether absence of the LDLR receptor affects a series of behavioral functions. We also took advantage of the fact that plasma cholesterol levels can be regulated in LDLR-/- mice by manipulating dietary cholesterol [31] to investigate whether modifying plasma cholesterol levels might independently affect behavioral performance. We show that while LDLR-/- mice perform normally on a variety of behavioral tests they exhibit increased locomotor activity. Thus the LDLR influences behavior in adult mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

C57BL/6J and LDLR-/- mice (stock # 002207 strain name B6.12957-Ldlrtm1Her) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). LDLR-/- mice were originally generated using a 129 ES cell line and have been backcrossed for ten generations onto the C57BL/6J background. Therefore as controls C57BL/6 wild type mice purchased simultaneously from Jackson were used as controls. Both LDLR-/- and C57BL/6 wild type mice arrived at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center (Bronx, NY) at the age of 8 weeks. Animals were housed at a constant 70-72° F temperature, with rooms on a 12:12 hour light cycle with lights on at 7 AM. All subjects were housed in standard clear plastic cages equipped with Bed-O'Cobs laboratory animal bedding (The Andersons, Maumee, OH) and EnviroDri nesting paper (TecniLab, Someren, The Netherlands). Access to food and water was ad libitum. After the first two weeks, subjects were transferred to individual housing. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the James J. Peters Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and were in conformance with the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.”

2.2. Dietary manipulations

Initially, all subjects received a standard lab chow diet (0.02% cholesterol and 6% fat, Lab Diet 5K52; Purina, St. Louis, MO). Four weeks after arrival, C57BL/6J and LDLR -/- mice were divided into groups that were fed either high (D12102N base diet with 0.15% cholesterol and 4.3% fat; Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) or low (D12102N base diet with 0.02% cholesterol and 4.3% fat) cholesterol diets. All subjects were maintained on these diets ad libitum, for the duration of the study.

2.3. Measurement of serum cholesterol

After completion of behavioral testing, blood samples were taken by either retro-orbital or sub-mandibular bleeds. Total plasma cholesterol levels were determined using the Infinity Cholesterol Reagent kit (Thermotrace, Arlington, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Testing schedule

After 16 weeks of the high/low cholesterol dietary regimen, 12 male mice from each of the 4 groups (high cholesterol C57BL/6J, low cholesterol C57BL/6J, high cholesterol LDLR -/-, low cholesterol LDLR -/-) were selected randomly for testing and moved to housing in an adjoining room. Subjects from all 4 groups were housed on racks in random order to prevent rack position effects, and cages were coded to allow maintenance of dietary groups during blind testing. Following habituation to the new room and handling, test order for all subjects consisted of (1) general observations and spontaneous activity battery; (2) elicited behavior battery; (3) locomotor activity and open field, grip strength and rotarod; (4) light/dark emergence; (5) Morris water maze; (6) prepulse inhibition and acoustic startle; and (7) tail flick analgesia.

2.5. General observations, spontaneous activity, and elicited behavior

All subjects were first evaluated for general health, reflexes, motor coordination, and strength with scoring performed as described in the SHIRPA protocol [27] (http://www.mgu.har.mrc.ac.uk/facilities/mutagenesis/mutabase/shirpa_summary.html). Following measurement of height and weight, subjects were observed in a 1000-mL beaker for 5 minutes, with note taken of the presence of normal behaviors (turning in both directions, rearing, and grooming), defecation and urination, and any abnormal behaviors. Subjects were scored on a variety of physical attributes, including coat condition, tremor, lacrimation, salivation, spontaneous piloerection, corneal and pinna reflexes, palpebral closure, whisker barbering, catalepsy, and skin color. Following transfer to a clean empty cage, subjects were screened for any abnormality in active exploration behavior or posture. After a break of several days to a week, each subject's response(s) was further scored for limb retraction upon toe-pinch, sensory neglect (latency to locate and remove small stickers affixed to each flank), righting reflexes (from surface and mid-air), visual placing (ability to gauge distance of an approaching platform before pinna contact), visual cliff (scoring latency to edge approach and head pokes over the edge in 1 minute), hind-limb placing on a vertical grid surface, ability to hang from a bar, negative/positive geotaxis (ability to right body and climb a vertical grid surface), transfer arousal upon introduction to an unfamiliar cage, and climbing behavior over a sloped metal bar cage lid. Other simple motor assays of grip strength and performance on a rotarod (increasing 0 to 50 rpm over 2 minutes) were performed concurrently with activity sessions.

2.6. Locomotor activity and open field

General locomotor activity and open field anxiety were examined together in four 16″ × 16″ Versamax activity monitors (Accuscan, Columbus, OH), each outfitted with a grid of 32 infrared beams at ground level and 16 elevated 3″ above ground level. All horizontal movement and rears were automatically tracked by beam breaks in 1-hour sessions run in dim lighting on 3 consecutive days for each subject. Samples were recorded in 1 minute bins for move time, move distance, velocity, rears, rotational behavior, thigmotaxis, and center time (defined as a subject's time with centroid 3″ or more from the monitor wall). Between runs, all cages were thoroughly wiped clean with water.

2.7. Light/dark emergence

Anxiety was tested by light/dark emergence. The assay was run (and subject behavior automatically tracked and quantified) in Versamax activity monitors with opaque black Plexiglas boxes enclosing the right halves of the interiors so that only the left sides were illuminated. Subjects began in the dark side and were allowed to freely explore for 10 minutes with access to the left (light) side through a 3″ × 1″ open doorway located in the center of the monitor. Measures of anxiety, namely light-side emergence latency, light side center latency (to a 4″ × 12″ rectangle, 2″ from the walls), and percent total light side duration were derived from beam breaks. Vertical sensors were disabled for the duration of the assay and subject side preference and emergence latencies were tracked by centroid location. All equipment was wiped clean with water between tests.

2.8 Elevated zero maze

Fear and anxiety were additionally tested in an elevated zero maze. The apparatus consisted of a circular black Plexiglas runway 24 inches in diameter and raised 24 inches off the ground (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA). The textured runway itself was 2 inches across and divided equally into alternating quadrants of open runway enclosed only by a 1/2 inch lip, and closed runway with smooth 6 inch walls. All subjects received a 5 five-minute trial on each of 2 consecutive days. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two groups, with half beginning the trial in the center of an open arc of runway on the first day, and in a closed arc of the runway on the second day. The other half were reversed starting in a closed arc on day 1 and an open arc on day 2. During each trial, subjects were allowed to move freely around the runway, with all movement being tracked automatically by a video camera placed on the ceiling directly above the maze and analyzed by EZ Video software (Accuscan) in 1-minute bins. Subject position was determined by centroid location. Data for all bins were pooled over each 5 minute trial for each subject, yielding measures of total movement time and distance for the entire maze, as well as time spent and distance traveled in each of the individual quadrants. From the quadrant data, measures of total open and closed arc times, latency to enter an open arc (for trials with a closed arc start), total open arm entries, and latency to completely cross an open arc between two closed arcs were calculated.

2.9. Morris water maze

Spatial memory was investigated using a Morris water maze paradigm. Trials were run in a 48″ plastic pool (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) of water opacified by the addition of non-toxic white tempura paint. Visual cues, in the form of bold cut-out shapes on the four walls surrounding the maze and on the pool walls themselves, allowed the subjects to orient themselves and locate a hidden platform (stepped, 4″ × 4″, San Diego Instruments) 1.5 cm below the surface of the water in the center of one quadrant. On the first day of the 2-week procedure, subjects were habituated to the pool in a 5 min trial with a visible platform extending just out of the water. Subjects were placed in the quadrant opposite the platform and in this as in all subsequent trials were started facing the wall. Subjects that failed to reach the platform within 5 minutes were gently guided to the platform by the tail and left on top of it for 30 seconds. In the next two sessions, training days 1 and 2, all subjects received 4 × 1 min trials to locate the still-visible platform, while for training days 3 through 8, water levels were raised to submerge and hide the platform on each of the 4 × 1 minute trials. In all training days, subjects began one trial in each quadrant, counterclockwise from a starting quadrant that also shifted clockwise one step each day. In this way, each subject received all possible trials each day, in one of 4 possible sequences, completing two full rotations over the 8 training days. On any training trial in which a subject failed to locate the platform, that subject was gently guided to the platform by the tail and allowed to rest on the platform for an additional 15 seconds before removal. Between trials, subjects were dried thoroughly with paper towels, placed under a heat lamp to maintain body temperature, and returned to their home cages for at least 10 minutes. On the final day, the platform was removed entirely and subjects were given a single 1-minute trial starting from the quadrant opposite the original platform location. All trials were recorded and automatically scored in EZ video (Accuscan). On training days, each subject's total elapsed time to find the platform was recorded, and the trial ended if the subject remained on the platform for 5 seconds or more. On the probe trial, latency to reach the target square, time spent in the target quadrant, time spent in the target square, and total distance swam during the probe trial were quantified along with time spent in all other quadrants and corresponding target areas.

2.10. Prepulse inhibition and acoustic startle

Startle magnitude and sensory gating were examined in a 40-trial prepulse inhibition assay (San Diego Instruments). Subjects were placed in isolation chambers inside closed Plexiglas tubes each of which was mounted on a platform resting on an accelerometer. Following a 5-minute habituation period with 74 dB background white noise, each subject received 40 randomized trials separated by 20 to 30 seconds. Trials consisted of 10 each of background readings taken at 74 dB, startle trials with readings following 40 ms 75, 80, 85, 90, 100 or 125 dB tones, prepulse inhibition trials where the 125 dB tone was preceded by a 20 ms 79 dB tone 100 ms earlier, and control trials consisting of only the 20 ms 79 dB prepulse. On all trials, maximum magnitude of the subject's startle (or other motion) was automatically recorded in 500 ms windows by the accelerometer. The tubes were rinsed clean with water between subjects. The formula 100 − [(startle response on acoustic prepulse plus pulse stimulus trials/pulse stimulus response alone trials) × 100] was used to calculate percent prepulse inhibition [24].

2.11. Tail flick analgesia

Pain threshold and skin sensitivity were evaluated with an automated tail-flick device (IITC, Woodland Hills, CA) that heated a point on a subject's tail via a concentrated light beam. Each subject was wrapped in a portion of a sheet to limit movement and placed with tail resting in a groove beneath the beam. When the subject's tail was removed from the beam, an automatic timer recorded the latency. All subjects received 5 tail-flick trials, separated by 1 minute. The tail-flick device was calibrated so that normal C57BL/6J animals respond within 5 to 10 seconds, and a maximum cut-off at 20 seconds ensured that no tissue damage could occur.

2.12. Statistical procedures

All data are presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were made using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc tests or paired t-tests. Statistical tests were performed using the program GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego CA) or SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago Il).

3. Results

3.1. Experimental design for manipulation of plasma cholesterol in LDLR-/- mice

C57BL/6J mice fed a high cholesterol diet develop at most mild elevations in plasma cholesterol. LDLR -/- mice fed a standard low cholesterol rodent chow diet (≈4-6% fat, 0.04% or less cholesterol) also develop only moderately increased plasma cholesterol levels and a slightly increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis [16,17,26]. However by increasing dietary cholesterol to 0.15% or greater [31], plasma cholesterol in LDLR-/- mice increases to over 1000 mg/dl, and within 16 weeks of dietary modification the animals develop extensive atherosclerotic lesions [2,20].

To test the effects of both the LDLR as well as elevated plasma cholesterol on behavioral function in LDLR-/- mice we fed C57BL/6J wild type mice and LDLR-/- mice either low (standard lab chow) or high cholesterol (0.15%) diets for 16 weeks at which time behavioral testing was begun. Testing was completed over an approximately 8-week time frame during which the mice were continued on standard lab chow or high cholesterol diets. Plasma cholesterol levels at the completion of behavioral testing are shown in Fig. 1. Plasma cholesterol in C57BL/6J mice fed a standard lab chow diet (C57BL-L) was between 105-110 mg/dl and did not significantly differ in C57BL/6J mice receiving the high cholesterol diet (C57BL-H). By contrast, plasma cholesterol was over 500 mg/dl in LDLR-/- mice fed the low cholesterol diet (LDLR-L) and was over 1300 mg/dl in LDLR-/- mice on the high cholesterol diet (LDLR-H). A two-way ANOVA revealed the expected effects of both diet (F 1, 44 = 308.4, p < 0.0001) and genotype (F 1, 44 = 69.93, p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction of diet and genotype (F 1, 44 = 66.56, p < 0.0001) with plasma cholesterol increased in both LDLR groups compared to the respective C57BL/6J groups and in the high vs. low cholesterol fed LDLR groups (p < 0.001, Bonferroni post-tests).

Fig. 1.

Plasma cholesterol in C57BL/6J wild type and LDLR-/- mice. C57BL/6J and LDLR-/- mice (N = 12 per genotype and diet condition) were fed either low (C57BL-L, LDLR-L) or high (C57BL-H, LDLR-H) cholesterol diets and blood was drawn for plasma cholesterol levels after completion of behavioral testing.

3.2. General observations, spontaneous activity, and elicited behavior

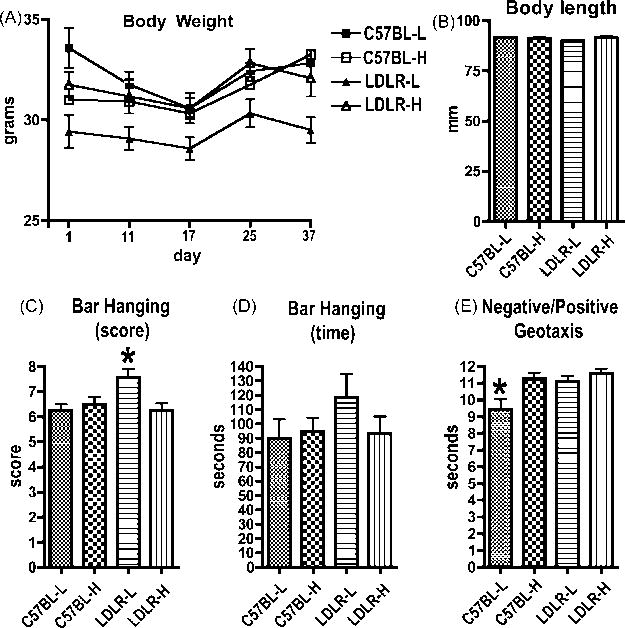

All animals were first evaluated for general health, certain stereotyped reflexes, motor coordination, and strength. The complete battery of tests administered is listed in Table 1. LDLR-L mice consistently weighed ≈6-7% less compared to C57BL/6J mice or LDLR-/- fed the high cholesterol diet (Fig. 2A) with two way ANOVAs showing the effect to be an interaction of diet and genotype (F values 2.5 to 6.9 and p values 0.01-0.11 for interaction; F values 0.018 to 1.864 and p values 0.17 to 0.89 for diet; F values 0.5 to 3.3 and p values 0.07 to 0.45 for genotype). Body length was unchanged (Fig. 2B). There were otherwise no abnormalities in any of the other general observations or tests of spontaneous behaviors listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

| General Observations: |

| Urination |

| Defecation |

| Turning |

| Grooming (latency) |

| Rearing |

| Body weight |

| Body length |

| Coat appearance |

| Skin color |

| Whisker barbering |

| Body positions/posture |

| Spontaneous piloerection |

| Spontaneous activity: |

| Pelvic elevation |

| Tremor |

| Salivation |

| Lacrimation |

| Palpebral closure |

| Catalepsy |

| Elicited behaviors (basic): |

| Corneal response |

| Pinna reflex |

| Touch escape |

| Toe pinch |

| Sensory neglect |

| Surface righting |

| Mid-air righting |

| Visual placing |

| Visual cliff |

| Hind limb placing |

| Hanging |

| Grip strength (fore paws) |

| Transfer arousal |

| Negative/positive geotaxis |

| Climbing behavior |

| Elicited behaviors (complex): |

| Locomotor activity |

| Rotarod (latency to fall, top speed) |

| Tail-flick latency |

| Morris water maze |

| Open field test |

| Elevated zero maze |

Fig. 2.

General observations, assessment of spontaneous activity and elicited behavior. Body weights (A) were obtained on the first day of behavioral testing as well as on the subsequent days indicated during the testing period that lasted seven weeks. LDLR-L mice weighted consistently less than mice in the other groups while body lengths (B) did not differ among the groups. The score in the bar hanging test (C) was determined by the following scale: 0 = mouse did not grasp the bar; 2 = mouse grasped the bar but fell off in less than 60 seconds; 3 = mouse grasped the bar and held on for longer than 60 seconds. Score represents the sum of three trials. LDLR-L mice scored better than the other groups. No differences were found in total time spent hanging on the bar (D). In negative/positive geotaxis (E) C57BL-L mice righted more quickly than the other groups. All groups contained 12 mice.

Among the tests of elicited behaviors, LDLR-L mice grasped better than all other groups in the hanging bar test (Fig. 2C), a test of neuromuscular strength with the effect resulting from an interaction of diet and genotype (F 1, 44 = 3.425, p = 0.07 for diet; F 1, 44 = 3.425; p = 0.07 for genotype; F 1, 44 = 7.329, p = 0.009 for interaction; p < 0.01 Bonferroni post-tests). The LDLR-L mice were however not significantly different from the other groups in total hang time (Fig. 2D). In the test of negative/positive geotaxis (Fig. 2E), C57BL-H, LDLR-L and LDLR-H took ≈ 2 seconds longer to right themselves than the C57BL-L controls, an effect of both diet and genotype (F 1, 44 = 7.512, p = 0.008 for diet; F 1, 44 = 5.480, p =0.02 for genotype; F 1, 44 = 2.448, p = 0.12 for interaction; p < 0.01 Bonferroni post-tests). All groups performed equally well on a rotarod (data not shown) and there were no differences between the groups in tail flick latency (data not shown). Thus in general, LDLR-/- mice exhibited no major deficits in sensory or motor function and there were no substantial effects of the high cholesterol diet.

3.3. Locomotor activity and open field

As a measure of general locomotor activity as well as anxiety, mice were examined in an open field chamber (Fig. 3). While there were no differences among the groups in the amount of time spent in the center vs. the periphery of the field on either day of testing, the LDLR groups traveled a greater distance (F 1, 36 = 4.285, p = 0.04 for genotype, day 1; F 1, 44 = 3.629, p = 0.06 for genotype, day 2) and spent more time in motion in the open field (F 1, 36 = 3.818, p = 0.05 for genotype, day 1; F 1, 44 = 5.271, p = 0.02 for genotype, day 2) than the C57BL/6J groups without any significant effect of diet or interaction effect. Consistent with the effect being due to an increased time spent in motion, the velocity of movement did not differ between groups. There were also no differences between the groups on either day in clockwise or counter clockwise revolutions, total revolutions, the ratio of clockwise to total revolutions, or rears (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Activity in open field-testing. General locomotor activity and anxiety were assessed in an open field chamber (N = 10, C57BL-L and C57BL-H; N = 11, LDLR-L; N = 9, LDLR-H). Shown are total distance moved (A, F) time spent in motion (B, G), velocity (C, H), as well as time spent in the center (D, I) vs. the periphery (E, J) of the open field on days 1 (A-E) and 2 (F-J) of testing.

All groups tended to show a test-retest habituation effect spending less time in motion on day 2 (paired t-tests, p = 0.02 for C57BL-L and C57BL-H; p = 0.07 for LDLR-L and p = 0.03 for LDLR-H) and traveling less distance (paired t-tests, p = 0.12 for C57BL-L; p = 0.006 for C57BL-H; p = 0.08 for LDLR-L and p = 0.04 for LDLR-H). However, in comparing the changes between day 1 and day 2, whether computing absolute differences or percent change between day 1 and day 2, there were no significant differences among the groups or any effect of diet or genotype, suggesting that neither absence of the LDLR nor the high cholesterol diet was influencing the habituation effect.

Any effects of altered anxiety would be expected to be most prominent in the initial minutes of testing. Since these effects might be lost in the 20-minute composite results as an additional measure of performance in the open field, we also analyzed center time and distance moved during each the first 10 minutes of open field testing during day 1. Center time for all groups progressively increased until about six minutes (Fig. 4A). We therefore analyzed center time and distance moved in three-minute intervals for the first 9 minutes (Figs. 4B-G). In the first three-minute interval (i.e. minutes 1-3), all groups moved similar distances. However, the LDLR groups traveled between 45 and 50% more than the C57BL groups in the second (F 1, 36 = 10.89, p = 0.002 for genotype) and third-three minute intervals (F 1, 36 = 9.759, p = 0.003 for genotype), without any significant effect of diet or interaction effect.

Fig. 4.

Activity in the initial minutes of the open field test. Shown is time spent in the center of the open field for the first ten minutes of open field-testing on day 1 (A) for the animals tested in figure 3. Also shown is total center time (B, D, F) and distance moved (C, E, G) analyzed in three minute intervals (minutes 1-3 in B, C; minutes 4-6 in D, E; minutes 7-9 in F, G) during the first 9 minutes of testing on day 1.

By contrast, while center time approximately doubled in all groups when comparing the third to the first three-minute interval (p < 0.008, paired t-test for each group), there were no differences between the groups. Thus, the increased distance traveled by the LDLR -/- groups is more parsimoniously explained as a hyperactivity response as opposed to altered anxiety.

An analysis of the distances moved on a minute-by-minute basis also showed a progressive decrease in the rate of movement that slowed in its rate of change for all groups after 5 minutes, and stopped increasing after 7 minutes (data not shown). In comparing the slopes over the 2-5 minute interval, slopes for the LDLR mice were significantly less negative (F 1, 36 = 4.6, p = 0.03 for genotype), consistent with hyperactivity in the LDLR mice.

3.4. Light/dark emergence

Light/dark exploration is an approach/avoidance test which explores the conflict between the tendency of mice to avoid a brightly lit open field vs. the tendency to explore a novel environment [6]. Due to its sensitivity to anxiolytic drugs, it is considered a measure of anxiety in mice [7]. Subjects were allowed to explore the dark chamber before access to the light was provided; the latency to emerge into and explore the light side was measured. As judged by the latency to first crossing the light edge, there were no significant differences between the groups (Fig. 5). However, the low cholesterol fed groups (C57BL-L and LDLR-L) spent more time at the light edge (light edge duration, F 1, 44 = 4.401, p = 0.04 for diet), and entered the center of the lighted field (light center latency, F 1, 44 = 4.873, p = 0.03 for diet) more quickly than groups fed the high cholesterol diet (C57BL-H and LDLR-H), without any significant effects of genotype or interaction effects.

Fig. 5.

Performance in light/dark emergence test. Shown are light edge latency (A), light edge entries (B), light edge duration (C), light center latency (D), light center entries (E), light total duration (F), dark edge distance (G) and dark total distance (H). All groups contained 12 mice.

The low cholesterol groups also showed a trend towards more light edge entries (p = 0.06), light center entries (p = 0.06) and a longer total light duration (p = 0.06), results that two way ANOVAs revealed were associated with diet and not genotype (Fig. 5). By contrast, LDLR mice had longer dark edge distances (F 1, 44 = 5.214, p = 0.02 for genotype), as well as a greater total distance moved in the dark (F 1, 44 = 6.756, p = 0.01 for genotype), without any significant effects of diet or interaction effects.

Thus no evidence was found for LDLR itself affecting anxiety levels although the increased distance moved in the dark by LDLR-/- mice may be another manifestation of the increased locomotor activity seen in LDLR-/- mice in the open field. These studies might also be seen as suggesting that a high cholesterol diet increases anxiety in both wild type as well as LDLR-/- mice. However, any effect appears task specific since diet had no effect on anxiety in the open field. In addition, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing of the number of specific measurements, none of the differences in the light/dark emergence task would be considered significant and thus must be interpreted with caution.

3.5 Elevated zero maze

As an additional test for altered anxiety in LDLR-/- mice, we also examined all groups in an elevated zero maze. No significant differences were found between the groups in open and closed arc times, or total open arm entries (Fig. 6). There was also no difference in the latency to enter an open arc or to cross an open arc between two closed arcs (data not shown). Thus as in the light/dark emergence task, no evidence was found for LDLR-/- mice having altered levels of anxiety. High cholesterol fed animals spent more time in motion on day 2 (F1, 36 = 5.013, p = 0.03 for diet, data not shown). However, all groups spent similar times in motion on day 1 and there were no differences between the groups on day in total distance moved (data not shown), suggesting no general effect of diet on tendency to move in this task.

Fig. 6.

Anxiety as assessed by an elevated zero maze. Shown is the amount of time spent in the open (A, B) or closed (B, D) portions of the arc as well as the number of open arm entries (E, F) on days 1 (A, C, E) and 2 (B, D, F) of testing (N = 11, C57BL-L and C57BL-H; N = 9, LDLR-L; N = 8, LDLR-H). There were no differences among the groups.

3.6. Morris water maze

Hypercholesterolemia has been suggested to be an independent risk factor for developing the memory impairments associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) [3,5,28]. In addition, a prior study reported that LDLR-/- mice exhibited impaired spatial memory in the Morris water maze [23]. We therefore assessed the effects of the LDLR mutation as well as elevated dietary cholesterol on spatial memory using the Morris water maze.

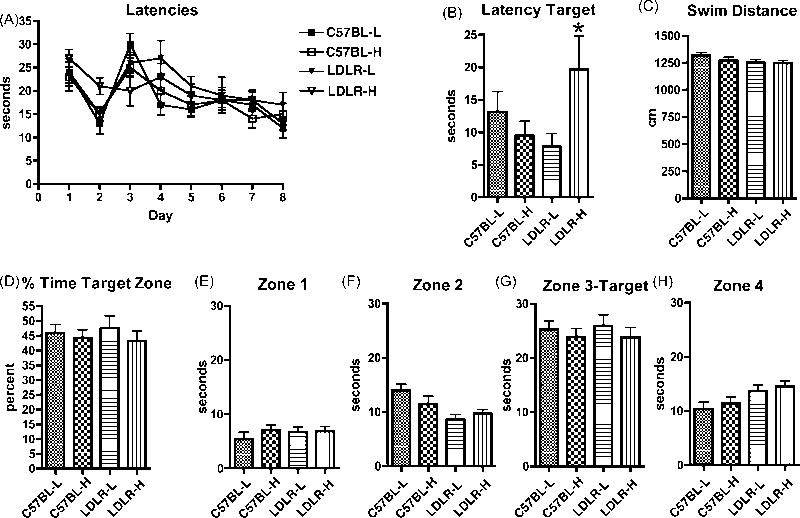

Latencies during the eight-day training period are shown in Fig. 6A. Slopes for days 3-8 were significantly different from zero at an 0.095 or better significance level for each group (p < 0.0005 for C57BL-L; p = 0.05 for C57BL-H and LDLR-L; p = 0.095 for LDLR-H, two-sided tests); the four groups did not differ significantly in their mean slopes suggesting that all groups learned the task. On the probe trial, LDLR-H mice took longer to reach the target site (Fig. 6B). This effect was found to result from an interaction of diet and genotype (F 1, 44 = 1.479, p = 0.23 for diet; F 1, 44 = 0.5160, p = 0.47 for genotype; F 1, 44 = 5.378, p = 0.02 for interaction) and does not appear to reflect altered locomotor competence since LDLR-H mice swam similar distances to the other groups during the probe trial (Fig. 6C). Moreover, all groups including the LDLR-H spent significantly more time exploring the target quadrant (Fig. 6G) indicating that all groups had learned the task (F values one way ANOVA, 32-41, p < 0.0001; Bonferroni post-tests p < 0.0001 for zone 3-target vs. each other quadrant). There were, in addition, no differences between the groups in the absolute time spent in the target quadrant (Fig. 6G), or the percent time spent in the target quadrant (Fig. 6D) during the probe trial. On balance these studies suggest that neither the LDLR genotype nor a high cholesterol diet have any major effects on performance in the Morris water maze.

3.7. Prepulse inhibition and acoustic startle

Acoustic startle response profile and prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle response were examined. All groups showed a significant prepulse inhibition when the 125 dB pulse tone was preceded by the 79 dB prepulse tone (Fig. 7, p ≤ 0.0005 for all groups, paired t-test). The groups did not consistently differ in their response to acoustic startle (data not shown) or degree of prepulse inhibition (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Spatial memory assessed by Morris water maze. Shown are escape latencies (A) during the training phase with the platform visible for days 1 and 2 and hidden for days 3-8. In the probe trial (B-H), results are shown for the latency to reach the target site (B), total swimming distance (C), percent time spent in the target quadrant (D) and time spent in the individual quadrants (E-H). All groups contained 12 mice.

4. Discussion

The LDLR was the first discovered of a large family of transmembrane receptors, several of which are known to play critical roles in regulating brain development. LDLR itself is expressed in the brain, and while it has generally been considered to be less important functionally in the nervous system [13] than other LDLR family members, several recent studies have suggested that LDLR may affect brain function [11,12,19,23]. We therefore undertook a detailed behavioral analysis of LDLR-/- mice and in addition given the interest in serum cholesterol as a possible risk factor for the cognitive dysfunction seen in AD [3,5,28], we used the fact that serum cholesterol levels can be modulated by diet in LDLR-/- mice [31] to examine the effects of systemic hypercholesterolemia on behavioral function as well.

Except for the LDLR-/- mice fed the low cholesterol lab chow diet being slightly smaller than the other groups, there were no obvious physical differences between the groups. We also found that in general LDLR-/- mice exhibited no major deficits in sensory or motor function and there were likewise no substantial effects of the high cholesterol diet on general motor or sensory function.

The most striking finding that distinguished LDLR mice from their C57BL/6J wild type controls was in the open field test where LDLR-/- mice spent more time in motion and moved a greater distance on both days of testing. The altered activity does not seem to be an effect of an altered anxiety levels, as LDLR and C57BL/6J mice spent comparable amounts of time in the center of the open field. There were also no genotype differences in the light/dark emergence or in the zero-maze tests to suggest that anxiety is altered by the absence of the LDLR, although while in the dark chamber LDLR-/- mice spent more time in motion, an additional indicator of increased locomotor activity. Collectively these studies thus seem best interpreted as indicating that LDLR-/- mice exhibit a general hyperactivity. Physiologically, these results suggest that LDLR regulates a general level of motor tone which is independent of anxiety and that the absence of LDLR leads to hyperactivity with a blunted response to at least some external sensory stimuli.

By contrast, serum cholesterol had little impact on behavior. Indeed, the only diet dependent effect seen was that in the light/dark test a high cholesterol diet appeared to increase some indices of anxiety in both wild type as well as LDLR-/- mice, an effect that cannot be due to serum cholesterol, per se, since wild type mice fed the high cholesterol diet did not develop elevated serum cholesterol. This effect while curious is hard to interpret in isolation, especially given the lack of any dietary effect on anxiety in the open field. The only other notable effect of cholesterol was that on the probe trial in the Morris water maze, LDLR-/- mice fed the high cholesterol diet had longer latencies to reach the target site, an effect dependent on both diet and genotype. However, this effect was likely to have been performance related since during the probe trial, the LDLR-H mice exhibited no other differences from the other groups, spending more time as well as a greater percentage of time exploring the target quadrant, indicating that the LDLR-H mice learned and remembered the task like all the other groups. Indeed while longer term exposure to elevated serum cholesterol may eventually impact behavior, the 16-week exposure studied here seems to have had few if any behavioral effects. This lack of effect is, however, consistent with our recent findings that dramatically elevated plasma cholesterol levels in LDLR-/- mice, whether induced by high cholesterol, high fat, or high fat/high cholesterol diets, do not substantially alter brain cholesterol levels nor affect levels of brain Aβ 40 or 42 [11].

Some aspects of our findings differ from a prior behavioral analysis of LDLR-/- mice [23] in which 26-week old LDLR-/- mice maintained on a low cholesterol lab chow diet were tested. Unlike our studies, they saw no changes in the behavior of LDLR-/- mice in the open field, while finding that in the Morris water, although LDLR-/- mice learned the task as judged by decreasing latencies during the acquisition phase, in the probe trial they spent no more time in the target quadrant than could be accounted for by chance [23]. In that study, memory impairment was also supported by the performance of LDLR-/- mice in a T-maze. The reasons for these differing results from those presented here is unclear. While the prior studies [23] also used only male mice with a stock originally obtained from the Jackson laboratories, they were performed after crossing to a distinct C57BL/6J background (C57Black/6J/Icco), raising the possibility that genetic background effects may account for the differing results. It is noteworthy that the mice in the current study received two more days of training (8 more trials) in the water maze than the mice in the Mulder et al. [23] study. It is possible that probe trial differences between groups could have been revealed following fewer learning trials. Yet whatever the explanation for the differing results, these studies suggest that while the absence of LDLR may produce no major developmental defects, LDLR nevertheless plays a role in modulating behavior in the adult.

Fig. 8.

Prepulse inhibition. Shown is the response to a 125 db tone without (A) or with a 79 db prepulse (B), the difference between pulse and prepulse (C), the pulse to prepulse ratio (D) and the percent prepulse inhibition (E). There were no differences among the groups (N = 11, C57BL-L; N = 12, C57BL-H, LDLR-L and LDLR-H).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant AG002219 from the National Institutes on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beeri MS, Rapp M, Silverman JM, Schmeidler J, Grossman HT, Fallon JT, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Siddiqui A, Lesser G, Rosendorff C, Haroutunian V. Coronary artery disease is associated with Alzheimer disease neuropathology in apoe4 carriers. Neurology. 2006;66:1399–1404. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210447.19748.0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslow JL. Mouse models of atherosclerosis. Science. 1996;272:685–688. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breteler MM. Vascular risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: An epidemiologic perspective. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casserly I, Topol E. Convergence of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease: Inflammation, cholesterol, and misfolded proteins. Lancet. 2004;363:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawley JN. Behavioral phenotyping of transgenic and knockout mice: Experimental design and evaluation of general health, sensory functions, motor abilities, and specific behavioral tests. Brain Res. 1999;835:18–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawley JN, Davis LG. Baseline exploratory activity predicts anxiolytic responsiveness to diazepam in five mouse strains. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8:609–612. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Defesche JC. Low-density lipoprotein receptor--its structure, function, and mutations. Semin Vasc Med. 2004;4:5–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehouck B, Dehouck MP, Fruchart JC, Cecchelli R. Upregulation of the low density lipoprotein receptor at the blood-brain barrier: Intercommunications between brain capillary endothelial cells and astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:465–473. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehouck B, Fenart L, Dehouck MP, Pierce A, Torpier G, Cecchelli R. A new function for the LDL receptor: Transcytosis of LDL across the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:877–889. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder GA, Cho JY, English DF, Franciosi S, Schmeidler J, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Fisher EA, Mathews PM, Haroutunian V, Buxbaum JD. Elevated plasma cholesterol does not affect brain Aβ in mice lacking the low-density lipoprotein receptor. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1220–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fryer JD, Demattos RB, McCormick LM, O'Dell MA, Spinner ML, Bales KR, Paul SM, Sullivan PM, Parsadanian M, Bu G, Holtzman DM. The low density lipoprotein receptor regulates the level of central nervous system human and murine apolipoprotein E but does not modify amyloid plaque pathology in PDAPP mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25754–25759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herz J, Bock HH. Lipoprotein receptors in the nervous system. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:405–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herz J, Gotthardt M, Willnow TE. Cellular signaling by lipoprotein receptors. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:161–166. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann SL, Russell DW, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. mRNA for low density lipoprotein receptor in brain and spinal cord of immature and mature rabbits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6312–6316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI116663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishibashi S, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Herz J, Burns DK. Massive xanthomatosis and atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1885–1893. doi: 10.1172/JCI117179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon H, Blacklow SC. Structure and physiologic function of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamada H, Hayashi T, Sato K, Iwai M, Nagano I, Shoji M, Abe K. Up-regulation of low-density lipoprotein receptor expression in the ischemic core and the peri-ischemic area after transient MCA occlusion in rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;134:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowles JW, Maeda N. Genetic modifiers of atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2336–2345. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesser G, Kandiah K, Libow LS, Likourezos A, Breuer B, Marin D, Mohs R, Haroutunian V, Neufeld R. Elevated serum total and LDL cholesterol in very old patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12:138–145. doi: 10.1159/000051248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucarelli M, Gennarelli M, Cardelli P, Novelli G, Scarpa S, Dallapiccola B, Strom R. Expression of receptors for native and chemically modified low-density lipoproteins in brain microvessels. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulder M, Jansen PJ, Janssen BJ, van de Berg WD, van der Boom H, Havekes LM, de Kloet RE, Ramaekers FC, Blokland A. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice display impaired spatial memory associated with a decreased synaptic density in the hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paylor R, Crawley JN. Inbred strain differences in prepulse inhibition of the mouse startle response. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s002130050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitas RE, Boyles JK, Lee SH, Hui D, Weisgraber KH. Lipoproteins and their receptors in the central nervous system. Characterization of the lipoproteins in cerebrospinal fluid and identification of apolipoprotein B,E(LDL) receptors in the brain. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14352–14360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell-Braxton L, Veniant M, Latvala RD, Hirano KI, Won WB, Ross J, Dybdal N, Zlot CH, Young SG, Davidson NO. A mouse model of human familial hypercholesterolemia: Markedly elevated low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and severe atherosclerosis on a low-fat chow diet. Nat Med. 1998;4:934–938. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers DC, Fisher EM, Brown SD, Peters J, Hunter AJ, Martin JE. Behavioral and functional analysis of mouse phenotype: SHIRPA, a proposed protocol for comprehensive phenotype assessment. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:711–713. doi: 10.1007/s003359900551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shobab LA, Hsiung GY, Feldman HH. Cholesterol in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:841–852. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The nun study. Jama. 1997;277:813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson LW, Simmons DM, Hofmann SL, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Localization of mRNA for low density lipoprotein receptor and a cholesterol synthetic enzyme in rabbit nervous system by in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9821–9825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teupser D, Persky AD, Breslow JL. Induction of atherosclerosis by low-fat, semisynthetic diets in LDL receptor-deficient C57BL/6J and FVB/NJ mice: Comparison of lesions of the aortic root, brachiocephalic artery, and whole aorta (en face measurement) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1907–1913. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000090126.34881.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolozin B. Cholesterol, statins and dementia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15:667–672. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200412000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]