Abstract

Melanoma development in interspecific hybrids of Xiphophorus is induced by the overexpression of the mutationally activated receptor tyrosine kinase Xmrk in pigment cells. Based on the melanocyte specificity of the transcriptional upregulation, a pigment cell specific promoter region was postulated for xmrk, the activity of which is controlled in healthy purebred fish by the molecularly still unidentified regulator locus R. However, as yet the xmrk promoter region is still poorly characterized. In order to contribute to a better understanding of xmrk expression regulation, we performed a functional analysis of the entire putative gene regulatory region of the oncogene using conventional plasmid based reporter systems as well as a newly established method employing BAC derived luciferase reporter constructs in melanoma and non-melanoma cell lines. Using the melanocyte specific mitfa promoter as control, we could demonstrate that our in vitro system is able to reliably monitor regulation of transcription through cell type specific regulatory sequences. We found that sequences within 200 kb flanking the xmrk oncogene do not lead to any specific transcriptional activation in melanoma compared to control cells. Hence, xmrk reporter constructs fail to faithfully reproduce the endogenous transcriptional regulation of the oncogene. Our data therefore strongly indicate that the melanocyte specific transcription of xmrk is not the consequence of pigment cell specific cis-regulatory elements in the promoter region. This hints at additional regulatory mechanisms involved in transcriptional control of the oncogene, thereby suggesting a key role for epigenetic mechanisms in oncogenic xmrk overexpression and thereby in tumor development in Xiphophorus.

Keywords: melanoma, Xiphophorus, xmrk oncogene, transcriptional control, pigment cell, EGF-receptor, tumor suppressor, cis-regulatory element

1. Introduction

Fish model systems have been used extensively in biomedical research to study human diseases, including a variety of tumors, such as hematological and liver cancers, sarcomas and melanoma (Amatruda and Patton, 2008; Bailey et al., 1996; Jing and Zon, 2011; Patton et al., 2010; Schartl, 2014). In contrast to most other fish cancer models, which are genetically engineered and based on transgenes often of human origin, the melanoma models in several species of the teleost genus Xiphophorus are based on a naturally occurring system of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. In these fish, carcinogen and UV induced as well as hereditary melanoma formation has been described and analyzed (Meierjohann and Schartl, 2006; Walter and Kazianis, 2001). The development of melanoma in Xiphophorus is always initiated by standardized crossing procedures and thus clearly defined genetic events are underlying melanoma initiation. In the case of hereditary melanoma, this guarantees the development of highly uniform tumors with respect to molecular and pathological features, making Xiphophorus a valuable tool to study the molecular processes of melanomagenesis.

The development of hereditary melanomas in certain interspecific backcross hybrids of platyfish (Xiphophorus maculatus) and swordtails (Xiphophorus hellerii), which was discovered already in the 1920s (Gordon, 1927; Häussler, 1928; Kosswig, 1928), has been attributed to the uncontrolled activity of a dominantly acting, pigment cell specific oncogene locus called Tu. According to the genetic model developed to explain melanoma development in Xiphophorus hybrids (Ahuja and Anders, 1976), the tumor-inducing potential of Tu is suppressed in purebred species (e.g. X. maculatus) by an unlinked regulatory locus R (also termed Diff (Vielkind, 1976; Walter and Kazianis, 2001)), which is supposed to act as a tumor suppressor. This suppression is progressively eliminated upon crossing when using a species as recurrent parent that contains neither Tu nor R (e.g. X. hellerii). In hybrid offspring heterozygous for Tu, but lacking the R locus, the R mediated suppression of Tu is lost, resulting in the formation of fast growing and highly malignant melanoma in these fish. However, it should be noted that the crossing data can formally also be explained by R being a tumor inducer contributed by swordtail chromosomes to the hybrid genome (Schartl, 1995).

Molecular genetic studies identified an oncogene called xmrk (Xiphophorus melanoma receptor kinase) as the primary tumor-determining gene of the Tu locus (Wittbrodt et al., 1989). Xmrk was generated by a local gene duplication event from the preexisting proto-oncogene egfrb (Adam et al., 1993; Volff et al., 2003), which is one of the two fish co-orthologs of the human EGF-receptor. The oncogenic properties of the xmrk encoded protein result from two activating mutations in the extracellular domain of the growth factor receptor, which lead to ligand independent dimerization and thus constitutive activation of the receptor (Gomez et al., 2001; Meierjohann et al., 2006a).

Shortly after the identification of xmrk, expression studies provided evidence that linked melanoma development in Xiphophorus to a specific overexpression of the xmrk oncogene (Adam et al., 1991; Mäueler et al., 1993; Woolcock et al., 1994). Based on these data, it was hypothesized that besides activating mutations in the Xmrk receptor, the second precondition for melanoma development is transcriptional activation of the xmrk oncogene. A quantitative analysis of xmrk transcript levels in different tissues of hybrid and parental Xiphophorus genotypes confirmed a positive correlation between the abundance of xmrk transcripts and the development and progression of melanoma (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). Furthermore, the data clearly demonstrated that transcriptional activation of the xmrk oncogene is restricted to the black pigment cell lineage of R-free backcross hybrids. This led to the conclusion that the xmrk oncogene is controlled by a pigment cell specific regulatory region, the activity of which is controlled by the R locus. Crossing dependent loss of R would thus result in a release of the transcriptional control of xmrk in melanocytes and the resulting overexpression of xmrk would consequently be the primary step that initiates tumor formation.

This hypothesis was further supported by comparing expression of a highly tumorigenic (mdlSd-xmrkB) and a non-tumorigenic (mdlSr-xmrkA) xmrk allele (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). Both alleles encode for the constitutively activated Xmrk protein. (For nomenclature of xmrk and mdl (macromelanophore-determining locus) alleles and a detailed description of Xiphophorus phenotypes and genotypes see Schartl and Meierjohann, 2010). In contrast to the tumorigenic xmrkB allele, which is highly overexpressed in malignant melanomas compared to benign lesions and healthy skin, transcription of the xmrkA allele in melanocytes is not influenced by elimination of the regulator locus R. Transcript levels of xmrkA remain at the same low level in R-free hybrids as in the wildtype platyfish, which possess two copies of R. This clearly demonstrates that transcriptional control of xmrk in pigment cells is causative for melanoma development in Xiphophorus.

Hence, all evidence indicates that the R locus controls tumor development in Xiphophorus on the transcriptional level by directly or indirectly downregulating xmrk transcription. However, as yet the molecular identity of the R locus encoded gene(s) has not been defined and there is no direct experimental proof for its suggested mode of action.

Moreover, the xmrk promoter region is still poorly characterized. Apart from a 460 bp fragment with more than 97% nucleotide identity (Volff et al., 2003), the putative promoter regions of xmrk and the proto-oncogene egfrb are completely different from each other. As result of the duplication event that has generated the xmrk oncogene, a single copy of a repetitive DNA element (called D locus) was integrated directly upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of xmrk (Adam et al., 1993; Volff et al., 2003). Interestingly, the new D locus derived upstream sequence contains TATA- and CAAT-like sequences at the expected distance from the TSS of the xmrk oncogene (Adam et al., 1993). The functional analysis of the most proximal 0.7 kb xmrkB promoter fragment (−675/+34) revealed the presence of an activating GC box element identical to the consensus binding site for the transcription factor Sp1 in close proximity to the TATA box of the oncogene. This element mediated high level transcriptional activation in Xiphophorus cell lines, but the 0.7 kb fragment showed no melanoma cell specificity in reporter gene assays (Baudler et al., 1997), strongly suggesting the existence of additional cis-regulatory elements outside the region so far analyzed. To unravel the molecular mechanism by which R controls xmrk induced melanoma development in Xiphophorus, the identification of such regulatory elements and the respective transcription factors is a precondition.

Here we present a comprehensive functional analysis of 200 kb xmrkB flanking sequences representing the entire putative gene regulatory region of the tumorigenic xmrkB allele using conventional plasmid based as well as BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome) derived luciferase reporter systems. Comparing transcriptional activity of xmrkB reporter constructs in cells of melanoma and non-melanoma origin, we found no sequence elements that mediated a pigment cell specific transcriptional activation. Hence, we could not reproduce the endogenous xmrk expression pattern in vitro using xmrkB luciferase reporter constructs. Our data therefore strongly suggest that additional mechanisms are involved in controlling the melanocyte specific transcriptional activation of xmrk and hint at a crucial role for DNA methylation changes in xmrk expression regulation and thereby in melanoma development in Xiphophorus.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

The Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM and the embryonic epithelial cell line A2 were cultured in F 12 medium (Gibco™, Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 28 °C. The PSM cell line was established from melanoma tissue of an adult F1 hybrid between a platyfish (X. maculatus) and an albino swordtail (X. hellerii) (Wakamatsu, 1981). PSM cells carry an mdlSp-type-xmrkA allele which is highly tumorigenic and leads to melanoma development already in F1 hybrids between platyfish and swordtails; but its sex chromosomal origin is unknown (Schartl and Meierjohann, 2010). The differential tumorigenic potential of mdlSp-type-xmrkA (tumorigenic) and mdlSr-xmrkA (non-tumorigenic) has been attributed to sequence variations in the regulatory region as the open reading frames of both xmrkA alleles encode for the mutationally activated Xmrk protein (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). The A2 cell line (Kuhn et al., 1979) is derived from the southern swordtail species X. hellerii (Fig. S1, S2). Embryonic epithelial cell lines derived from X. maculatus (SdSr24) and X. hellerii (XhIII, FOI8) (Altschmied et al., 2000) were maintained in DMEM medium (Gibco™, Life Technologies), 15% FCS in the presence of penicillin/streptomycin at 28 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

2.2. RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures using TRIzol® Reagent (Life Technologies) according to the supplier’s recommendations. After DNase I treatment, reverse transcription was performed from 2 μg of total RNA using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies) and random hexamer primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses were performed on cDNA from 50 ng of total RNA. Amplification was monitored with Mastercycler® ep realplex (Eppendorf) using SYBR Green reagent. For quantification, data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) and normalized to expression levels of the housekeeping gene elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (ef1a). PCR values for each cDNA were determined from triplicates and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three independent reverse-transcribed RNA samples. PCR primers were designed using the Primer3 software version 0.4.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). The primers had the following sequences: Ef1a_fw: 5′-AGTGAAATCCGTGGAGATGC-3′, Ef1a_rev: 5′-ATCTGACCTGGGTGGTTCAG-3′, Xmrk_fw: 5′-ACGCATCTGGAAAATGAACA-3′, Xmrk_rev: 5′-AGCGCCCAGGATTAAAACAT-3′, Egfrb_fw: 5′-TCTGGAAAATGGAGCCAAAC-3′, Egfrb_rev: 5′-CCACATGTGAGAGCAGGAGA-3′, Mitfa_fw: 5′-ATCCCAAAATGCTGGAGATG-3′, Mitfa_rev: 5′-CAGGTACTGCCTCACCTGCT-3′.

2.3. Plasmids

Plasmids pLUC+, pTATALUC+ and ptkLUC+ are reporter constructs containing the luc+ firefly luciferase gene. pLUC+ is promoterless, whereas pTATALUC+ and ptkLUC+ contain 5′ deletions of the HSV TK promoter ending at −32 (TK derived TATA box) and −105 (TK promoter), respectively (Altschmied and Duschl, 1997). The plasmid pLUC+-9.3kbxmrkB was constructed by replacing the 1.7 kb XhoI/NgoMIV fragment from pLUC+ containing the luc+ gene with the 11 kb XhoI/NgoMIV fragment from BAC-LUC+-9.3kbxmrkB (for description see section 2.4) containing the luc+ gene under control of a 9.3 kb xmrkB promoter fragment (−9273/+61). A 5′ deletion series of the xmrkB promoter was generated using the restriction sites XhoI/AjiI, XhoI/NotI, XhoI/SmiI and XhoI/EcoRV, resulting in pLUC+-6.4kbxmrkB (−6370/+61), pLUC+-4.2kbxmrkB (−4174/+61), pLUC+-1.9kbxmrkB (−1875/+61) and pLUC+-0.8kbxmrkB (−761/+61), respectively, after religation of the remaining plasmid sequences. For generation of smaller deletion constructs, xmrkB promoter sequences were amplified by PCR with primers containing HindIII and CpoI restriction sites. The PCR products were cut with HindIII and CpoI and cloned into the HindIII/CpoI digested 4.5 kb fragment of plasmid pLUC+-0.8kbxmrkB. This resulted in plasmids pLUC+-665bpxmrkB (−665/+61), pLUC+-585bpxmrkB (−585/+61), pLUC+-445bpxmrkB (−445/+61), pLUC+-306bpxmrkB (−306/+61), pLUC+-110bpxmrkB (−110/+61), pLUC+-50bpxmrkB (−50/+61), pLUC+-39bpxmrkB (−39/+61) and pLUC+-5UTRxmrkB (0/+61).

For cloning of xmrkB promoter fragments into the pGL4.20 vector (Promega) containing the luc2 firefly luciferase reporter gene, xmrkB promoter sequences were amplified by PCR with primers containing XhoI and HindIII restriction sites. The PCR products were cut with XhoI and HindIII and cloned into plasmid pGL4.20 opened with the same enzymes. This resulted in plasmids pGL4.20-0.8kbxmrkB, pGL4.20-110bpxmrkB, pGL4.20-50bpxmrkB and pGL4.20-39bpxmrkB. Plasmid pGL4.20-9.3kbxmrkB was constructed by replacing the 0.8 kb xmrkB promoter fragment of plasmid pGL4.20-0.8kbxmrkB with the 9.3 kb xmrkB promoter fragment of plasmid pLUC+-9.3kbxmrkB using XhoI and CpoI restriction sites. To obtain pGL4.20 vectors containing HSV TK promoter fragments ending at −105 (pGL4.20-tkmini) and −32 (pGL4.20-tkTATA), these fragments were amplified by PCR using ptkLUC+ as template. The primers used for amplification introduced an XhoI and a HindIII restriction site, enabling cloning into the XhoI/HindIII digested 5.4 kb fragment of plasmid pGL4.20.

The mitfHGFP plasmid (Schartl et al., 2009) contains a 1 kb fragment of the mitfa promoter from Oryzias latipes. The mitfa promoter fragment was PCR amplified and cloned into the SalI/BamHI digested pLUC+ and the KpnI/NheI digested pGL4.20 vector, thus obtaining pLUC+-OLAmitfa and pGL4.20-OLAmitfa, respectively. pGL4.74 and pRL-CMV (Promega) are commercially available plasmids containing the renilla luciferase gene under control of the HSV TK and the CMV promoter, respectively. All plasmid constructs used in this study were verified by sequencing. Sequences of primers used for plasmid construction are given in Supplementary Table 1.

2.4. BAC recombineering

The generation of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) reporter constructs using homologous recombination was performed as described previously (Nakamura et al., 2008), with the following modifications: PCR amplification of the targeting fragment for homologous recombination was performed using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) with the following conditions: initial denaturing at 98 °C for 30 sec, followed by 30 amplification cycles of 98 °C for 20 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 2 min, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min. For electroporation, EasyjecT (EquiBio) and 0.2 cm wide electroporation cuvettes (Bio-Rad) were used. Extraction and purification of BAC DNA was conducted using a customer adapted protocol for the QIAGEN Plasmid Midi Kit (https://www.qiagen.com/de/resources/resourcedetail?id=ab7c2c09-8f47-403b-aaa6-18deef55e80e&lang=en).

BAC clones encompassing mdlSr-xmrkA (BAC-A6), mdlSd-xmrkB (BAC-A3) or the Y chromosomal egfrb allele (BAC-A4) are derived from a genomic BAC library of X. maculatus (strain WLC 1274, Rio Jamapa) (Froschauer et al., 2002) from which contigs covering several megabases of the sex-determining region on the X and Y chromosomes had been assembled and sequenced.

To generate the full length BAC reporter constructs BAC-xmrkA-LUC+, BAC-xmrkB-LUC+ and BAC-egfrb-LUC+, targeting DNA fragments for homologous recombination containing the firefly luciferase gene luc+ (5′-luc+-poly(A)-KmR-3′) were amplified by PCR using the pLUC+Km vector (kindly provided by Lisa Osterloh) and primers BAC_xmrkA_LUC+_fw/rev, BAC_xmrkB_LUC+_fw/rev and BAC_egfrb_LUC+_fw/rev, respectively. These DNA fragments were subsequently inserted into BAC-A6, BAC-A3 and BAC-A4 at the translational start sites of xmrk or egfrb by homologous recombination.

The BAC-67kbxmrkB-LUC+ deletion construct was generated by inserting a targeting DNA fragment containing an ampicillin resistance gene (AmpR) into BAC-xmrkB-LUC+ by homologous recombination, resulting in deletion of all xmrkB exons, introns and 3′ flanking sequences. This DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using the pRL-TK vector (Promega) and the primer pair BAC_xmrkB_67kb_fw/rev. The pLUC+Km vector and primers BAC_xmrkB_28kb_fw/rev were used for PCR to obtain a linear DNA fragment containing a kanamycin resistance gene (KmR), which was inserted by homologous recombination into BAC-67kbxmrkB-LUC+ to generate BAC-28kbxmrkB-LUC+. For construction of BAC-19kbxmrkB-LUC+ and BAC-9.3kbxmrkB-LUC+, targeting DNA fragments containing a zeocin resistance gene (ZeoR) were amplified by PCR using the pcDNA3.1/Zeo(+) vector (Life Technologies) and primers BAC_xmrkB_19kb_fw/rev and BAC_xmrkB_9.3kb_fw/rev, respectively. These targeting fragment were subsequently inserted into BAC-28kbxmrkB-LUC+ by homologous recombination.

The Oikopleura dioica BAC clone OIKO003 5xk14 (GenBank accession no. NG_007518.1) (Seo et al., 2001), which was a kind gift from Daniel Chourrout (Sars International Centre forMarineMolecular Biology, Bergen, Norway), was used to generate BAC reporter constructs of similar lengths as the test constructs containing the renilla luciferase gene Rluc under control of the CMV enhancer and immediate/early promoter element. These constructs were used for normalization of firefly luciferase activity. For the generation of the full-length reporter construct (BAC-RLUC), a targeting DNA fragment (5′-CMV-Rluc-poly(A)-AmpR-3′) was prepared by PCR using the pRL-CMV vector (Promega) and primers BAC_RLUC_fw/rev, which was subsequently inserted into BAC clone OIKO003 5xk14 by homologous recombination. To generate an 85 kb BAC-RLUC deletion construct (BAC-RLUC-85kb), a targeting DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using the pETM-30 vector and primers BAC_RLUC_85kb_fw/rev. The DNA fragment containing a KmR was subsequently inserted into BAC-RLUC by homologous recombination. The pLUC+Km vector and primers BAC_RLUC_40kb_fw/rev were used for PCR to obtain a linear DNA fragment containing an AmpR, which was inserted into BAC-RLUC-85kb by homologous recombination to generate BAC-RLUC-40kb. For construction of BAC-RLUC-30kb and BAC-RLUC-20kb, targeting DNA fragments containing a ZeoR were amplified by PCR using the pcDNA3.1/Zeo(+) vector (Life Technologies) and primers BAC_RLUC_30kb_fw/rev and BAC_RLUC_20kb_fw/rev, respectively. These targeting fragment were subsequently inserted into BAC-RLUC-40kb by homologous recombination. Sequences of primers used for homologous recombination are given in Supplementary Table 2.

2.5. Luciferase reporter assays

A2 and PSM cells were seeded in 12 well plates at a density of 2×105 and 8×104 cells per well, respectively. On the next day (d0), cells were transfected in conditioned medium using FuGENE® HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). For luciferase assays using BAC derived reporter constructs, firefly and renilla luciferase reporter constructs were cotransfected in a 2:1 molar ratio. For transfection of one well of a 12 well plate, 1 μg of the respective firefly luciferase BAC reporter construct was used. After 16-18 h (d1), medium was changed. On d2, cells were transferred to a 6 cm plate. On d7, cells were harvested in 50 μl of 1x PLB (Promega). For plasmid based luciferase reporter systems, firefly and renilla luciferase constructs were cotransfected in a 5:1 molar ratio using 1 μg total plasmid DNA per well. Medium was changed after 16-18 h, and on d2, cells were harvested in 60 μl of 1× PLB (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega) and the TriStar LB941 microplate multimode reader (Berthold Technologies). For each experiment, cells were seeded and transfected in triplicates. Unless noted otherwise, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three or four independently performed experiments and significance was determined using Welch’s t-test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, n.s.: not significant).

2.6 Genotypic characterization of A2 cells

Genomic DNA from cell cultures and pooled tissues of X. maculatus (strain WLC 1274, origin Rio Jamapa) was isolated using standard procedures. PCR amplification was performed using 10-100 ng gDNA and Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) according to the supplier’s instructions. cdkn2ab promoter sequences were amplified using the following primers: cdkn2ab_Xmac_f01: 5′-GTGCACTGCAACTTGCTTTC-3′, cdkn2ab_r01: 5′-CGGTGTGTGTCCGGGCTT-3′, cdkn2ab_f02: 5′-GCTTGCGAAGCTTTGAAGGG-3′, cdkn2ab_r02: 5′-CGCCGATAAACTACTCACAGC-3′. After amplification, PCR products were separated on 2 % agarose gels.

We used published primers for amplification of the complete cds of the cytochrome b gene (primer H15982 and L14725) (Hrbek et al., 2007) and the full length mitochondrial control region (primers H693 and L15513) (Schories et al., 2009) from A2 cells. PCR products were purified and sequenced using the same primer pairs as for amplification. All sequences were visually inspected and each determined sequence was confirmed from two independent PCR and sequencing reactions. For phylogenetic tree construction, published sequences of the mitochondrial control region (GenBank accession nos. DQ235834.1, DQ235823.1, DQ235826.1, DQ235833.1, DQ235814.1, DQ235832.1, DQ235829.1, DQ235818.1, DQ235835.1, DQ235827.1) and the cytochrome b gene (GenBank accession nos. EF017549.1, EF017552.1, EF017551.1, EF017548.1, EF017550.1) from several Xiphophorus species were used. Sequence alignments were obtained with Clustal W (Thompson et al., 1994) as implemented in BioEdit (Hall, 1999). For tree reconstruction, maximum-likelihood analysis was performed using MEGA 5.05 software (Tamura et al., 2011) according to the Tamura-Nei model of nucleotide substitutions. Bootstrapping values for the maximum-likelihood tree were obtained from 500 iterations.

3. Results

3.1. The Xiphophorus cell lines A2 and PSM provide a suitable system to analyze pigment cell specific cis-regulatory elements

As the regular primary approach to identify cis-regulatory elements important for a pigment cell specific transcriptional activation of the xmrk oncogene, we analyzed the transcriptional activity of xmrk promoter sequences in cells of melanoma and non-melanoma origin using luciferase reporter assays. To verify that the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM and the non-melanoma cell line A2 are suitable to monitor pigment cell specific transcriptional activation in reporter gene assays, we analyzed activity of a known pigment cell specific promoter in these cells. To this end, the proximal 1057 bp of the mitfa promoter from Oryzias latipes, a fish closely related to Xiphophorus, were used. The pigment cell specificity of this promoter fragment has been demonstrated in vivo in transgenic experiments (Schartl et al., 2009). The promoter fragment was inserted upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in vector pLUC+ and the newly generated construct was cotransfected with the renilla luciferase vector pRL-CMV in A2 and PSM cells. As a reference, firefly luciferase reporter constructs containing either the Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV TK) promoter or a TK promoter derived TATA box element were included in the experiment. In the melanoma cell line PSM, the mitfa promoter fragment showed a robust transcriptional activity (Fig. 1A). Compared to activity of the TK promoter derived TATA box element, activity of the mitfa promoter was increased 14 fold. In the embryonic fibroblast cell line A2, in contrast, transcriptional activity of the mitfa reporter construct was on a similar level as the construct containing the TK promoter derived TATA box (Fig. 1B), indicating that the mitfa promoter is transcriptionally not activated in this cell line. A similar result was obtained using an alternative set of vector backbones for generation of luciferase reporter constructs (Fig. 1C, D). Here, activity of the mitfa promoter was increased 17 fold compared to activity of the TK promoter derived TATA box element in the melanoma cell line PSM (Fig. 1C). In line with this, high levels of endogenous mitfa transcripts were found in PSM cells, whereas expression in A2 cells could not be detected by qPCR analysis (Fig. 2A). Taken together, this clearly demonstrates that the cell lines used for luciferase reporter assays in this study are suitable to detect pigment cell specific regulatory sequences.

Figure 1. Transcriptional activity of mitfa promoter sequences in Xiphophorus melanoma and non-melanoma cell lines.

Reporter constructs containing the firefly luciferase gene under control of the mitfa promoter from Oryzias latipes were transiently transfected into the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM (A, C) and the non-melanoma cell line A2 (B, D). Reporter constructs containing the firefly luciferase gene without promoter (empty) or under control of either the Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (TK) or the TK promoter derived TATA box element (TATA) were transfected as reference. Activity of firefly luciferase was normalized to activity of a cotransfected vector containing the renilla luciferase gene under control of either the CMV (pRL-CMV) or the HSV TK (pGL4.74) promoter. For (A) and (B) promoter sequences were inserted into pLUC+ and pRL-CMV was used for normalization, for (C) and (D) vectors pGL4.20 (firefly luciferase) and pGL4.74 (renilla luciferase) were used.

Figure 2. Analysis of endogenous expression levels in Xiphophorus cell lines.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of (A) mitfa, (B) xmrk and (C) egfrb transcript levels in the melanoma cell line PSM and in non-pigment cell lines. For mitfa and egfrb, endogenous expression was determined in the X. hellerii derived embryonic epithelial cell line A2. This cell line was also used for reporter gene assays. However, as A2 cells do not contain the xmrk gene, endogenous expression of xmrk was determined in the X. maculatus derived epithelial-like cell line SdSr24.

3.2. The proximal 9.3 kb of the xmrkB 5′ flanking region do not induce pigment cell specific transcriptional activation in reporter gene assays

As reference for the in vitro activity of xmrk reporter constructs in PSM and A2 cells, we at first determined endogenous xmrk transcript levels in Xiphophorus cell lines by qPCR analysis. In the melanoma cell line PSM, high levels of endogenous xmrk transcripts were detected (Fig. 2B). Hence, a strong, melanocyte specific transcriptional activation of xmrkB reporter constructs has to be expected in these cells. The embryonic fibroblast cell line A2 is derived from X. hellerii (Fig. S1, S2) and thus is devoid of xmrk. For analysis of endogenous xmrk transcript levels in non-pigment cell lines, we used the X. maculatus fibroblast cell line SdSr24. In these cells, endogenous expression of xmrk could not be detected by qPCR analysis (Fig. 2B). Consequently, none or only a background activity of xmrkB reporter constructs can be expected in the non-pigment cell line A2. Table 1 summarizes the endogenous xmrk expression levels and expected in vitro activities of xmrk reporter constructs in the different cell lines.

Table 1.

Summary of expected and observed endogenous xmrk expression levels and in vitro activities of xmrkA and xmrkB reporter constructs in the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM and in the non-pigment cell lines A2 and SdSr24.

| endogenous xmrk | expression | activity of xmrk flanking sequences in reporter assays | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| expected | observed | expected | observed | |

| A2 cells | n/a | n/a | both alleles: no/weak activation | both alleles: strong activation |

| SdSr24 cells | low | low | both alleles: no/weak activation | n/d |

| PSM cells | high | high | xmrkB: strong activation, presence of pigment cell specific cis- regulatory elements | xmrkB: strong activation, no pigment cell specific cis- regulatory elements |

| xmrkA: weak activation | xmrkA: strong activation | |||

n/a: not applicable, n/d: not determined.

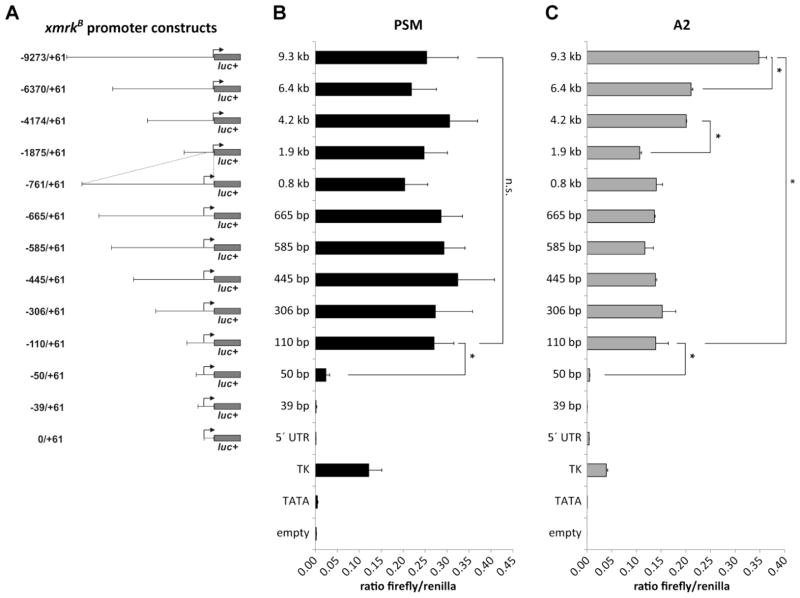

As previous data indicated that the putative regulatory elements responsible for the pigment cell specific transcriptional regulation of the tumorigenic xmrkB allele should be located upstream of position −675 in the xmrkB 5′ flanking region (Baudler et al., 1997), a larger xmrkB promoter fragment containing 9.3 kb upstream of the transcription start site plus the full length xmrkB 5′ UTR (−9273/+61) was inserted into vector pLUC+ and used for subsequent analyses. To determine the positions of promoter elements important for transcriptional control of xmrkB, a set of 5′ deletions spanning this segment of the putative xmrkB promoter region was generated (Fig. 3A) and transcriptional activity was quantified in PSM and A2 cells.

Figure 3. Functional analysis of the proximal 9.3 kb of the putative xmrkB promoter region.

Transcriptional activity of luciferase reporter constructs containing a set of 5′ deletions spanning the proximal 9.3 kb of the xmrkB upstream region (A) was measured following transfection into the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM (B) and the non-melanoma cell line A2 (C). Reporter constructs containing the firefly luciferase gene without promoter (empty) or under control of either the Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (TK) or the TK promoter derived TATA box element (TATA) were transfected as reference. All firefly luciferase reporter constructs were generated by inserting promoter sequences into pLUC+. For normalization of firefly luciferase activity, pRL-CMV containing the renilla luciferase gene Rluc under control of the CMV promoter was cotransfected. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of two independently performed luciferase experiments.

In the melanoma cell line PSM, deletion of the region between 110 bp and 50 bp upstream of the xmrkB TSS led to a significant reduction in reporter gene activity to about 10% of activity of the −110/+61 construct (p = 0.0368) (Fig. 3B). Deletion of sequences between 50 bp and 39 bp upstream of the TSS resulted in further reduction of reporter gene activity, reaching a basal level comparable to that of the TK promoter derived TATA box element. This strongly indicates the presence of important positive cis-regulatory elements in the region downstream of position −110. However, as this region led to a similar activation of transcription in the non-melanoma cell line A2 (Fig. 3C), these elements might not be responsible for mediating a pigment cell specific transcriptional activation of xmrkB, but drive transcription of the oncogene in a non-tissue specific manner. In PSM cells, putative regulatory elements could not be detected in regions further upstream, as the stepwise deletion of promoter sequences located between 9.3 kb and 110 bp upstream of the TSS of xmrkB did not lead to any significant change in promoter activity (Fig. 3B). The absence of promoter elements driving pigment cell specific transcriptional activation in the xmrkB 5′ flanking region was surprising. Based on the endogenous xmrk expression level in PSM cells (Fig. 2B) and data from extensive expression studies from normal and melanomatous tissues (Regneri and Schartl, 2012), a strong, pigment cell specific activity of xmrkB promoter sequences was expected in melanoma cells. In contrast to the situation found in PSM cells, promoter sequences located between 9.3 kb and 110 bp upstream of the xmrkB TSS significantly increased transcriptional activity in A2 cells by 2.5 fold (p = 0.0178) (Fig. 3C). Deletion from −9.3 kb to −6.4 kb as well as deletion from −4.2 kb to −1.9 kb resulted in a significant decrease in promoter activity (p = 0.0420 and p = 0.0115, respectively), indicating the presence of two potential positive cis-regulatory elements within this region. The finding that xmrkB promoter sequences specifically increase reporter gene transcription in a non-melanoma cell line was highly unexpected as the xmrkB oncogene is assumed to be controlled by a pigment cell specific promoter region. Moreover, xmrkB expression was not detectable in the X. maculatus fibroblast cell line SdSr24 (Fig. 2B).

Transcription factor binding sites in the vector backbone are problematic as they can lead to anomalous transcription, thereby distorting the results of luciferase reporter gene assays. To diminish the possibility that anomalous transcription is responsible for the unexpected transcriptional activity of xmrkB promoter sequences found in the previous experiment, we repeated the experiment using a vector for generation of luciferase reporter constructs, which contains a reduced number of consensus transcription factor binding sites. To this end, selected xmrkB promoter fragments were inserted into pGL4.20 upstream of the firefly luciferase gene (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, to exclude the possibility that the control promoter used for normalization causes distortion of results, we used the HSV TK instead of the CMV promoter to drive expression of the renilla luciferase. As found in the previous experiment, promoter sequences located between 110 bp and 39 bp upstream of the xmrkB TSS significantly increased promoter activity in PSM (p = 0.0077) (Fig. 4B) and A2 cells (p = 0.0106) (Fig. 4C). However, using the newly generated reporter constructs, the strong increase in promoter activity in A2 cells mediated by regions upstream of −0.8 kb could not be detected (Fig. 4C). In both cell lines, deletion of promoter sequences located between 9.3 kb and 110 bp upstream of the TSS of xmrkB did not lead to any significant change in promoter activity. Taken together, we found that promoter sequences located within the proximal 9.3 kb upstream of the xmrkB oncogene do not induce pigment cell specific transcriptional activation in reporter gene assays.

Figure 4. Transcriptional activity of selected xmrkB promoter fragments determined using pGL4 luciferase reporter vectors.

Firefly luciferase reporter constructs containing selected xmrkB promoter deletion fragments (A) were transfected into the Xiphophorus melanoma cell PSM (B) and the non-melanoma cell line A2 (C). Reporter constructs containing the luc2 firefly luciferase gene without promoter (empty) or under control of either the TK promoter (TK) or the TK promoter derived TATA box (TATA) were transfected as reference. All firefly luciferase reporter constructs were generated by inserting promoter sequences into pGL4.20. For normalization of firefly luciferase activity, pGL4.74 containing the renilla luciferase gene hRluc under control of the HSV TK promoter was cotransfected.

3.3 BAC derived reporter constructs containing up to 200 kb flanking region fail to reproduce the endogenous xmrkB expression pattern

One intuitive explanation for the finding that proximal promoter regions do not induce pigment cell specific transcriptional activation could be that the relevant, pigment cell specific regulatory elements are located outside the region so far analyzed. Distal cis-regulatory elements such as enhancer and silencer elements, which often contribute to the spatial transcription pattern of genes, have been found up to over hundred kb up- or downstream of the proximal promoter (Maston et al., 2006; Miele and Dekker, 2008) and therefore are often missed in conventional plasmid based reporter constructs. To overcome this problem, we established a luciferase assay using a BAC clone containing the xmrkB gene for generation of firefly luciferase reporter constructs (Fig. 5A). As the full length BAC reporter construct encompasses the entire genomic locus of the xmrkB gene, including surrounding regulatory elements in their natural position, it was expected to faithfully reproduce the endogenous xmrkB expression pattern. As a first approach to search for distal regulatory elements important for transcriptional control of xmrkB, we generated deletions of the full length xmrkB BAC reporter construct (Fig. 5A) and determined transcriptional activity in the melanoma cell line PSM and the non-melanoma cell line A2. This approach should provide evidence how different parts of the xmrkB flanking region influence transcriptional activity.

Figure 5. Transcriptional activity of BAC derived reporter constructs containing up to 200 kb xmrkB flanking sequences in cells of melanoma and non-melanoma origin.

(A) Schematic drawing of the full length xmrkB BAC reporter construct (BAC-xmrkB-LUC+) and various deletion constructs containing between 67 kb and 9.3 kb xmrkB 5′ flanking sequences. The full length reporter construct was generated by inserting the firefly luciferase gene luc+ together with a selection marker at the translational start site of xmrkB. Deletion constructs were generated subsequently by BAC recombineering. Transcriptional activity of full length and deletion constructs was measured in the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM (B, D) and in the X. hellerii embryonic fibroblast cell line A2 (C, E). For normalization, BAC reporter constructs containing the renilla luciferase gene Rluc under control of the CMV promoter were cotransfected. As differences in the transfection rates between BAC constructs of different size can lead to distortion of luciferase data, the cotransfected renilla luciferase BACs had the same size as the corresponding firefly luciferase reporter constructs. BAC-xmrkB-LUC+, BAC-67kbxmrkB-LUC+, BAC-28kbxmrkB-LUC+, BAC-19kbxmrkB-LUC+ and BAC-9.3kbxmrkB-LUC+ were cotransfected with BAC-RLUC, BAC-RLUC-85kb, BAC-LUC-40kb, BAC-RLUC-30kb and BAC-RLUC-20kb, respectively.

To determine whether important distal regulatory elements are located downstream of the proximal promoter in introns or 3′ flanking sequences, transcriptional activity of the full length xmrkB BAC reporter construct was compared to activity of a deletion construct containing the full length xmrkB 5′ region, but lacking the xmrkB gene and the regions downstream thereof (67 kb upstream). Deletion of these regions increased transcriptional activity in PSM cells by 2.2 fold (p = 0.0007) (Fig. 5B), whereas transcriptional activity in the non-melanoma cell line A2 was decreased (p = 0.0238) (Fig. 5C), indicating that sequences downstream of the proximal promoter do not induce pigment cell specific transcriptional activation of xmrkB. The increased activation of reporter gene expression in PSM cells rather indicates the presence of silencer elements specifically repressing transcription in melanoma cells in this region. The presence of such elements in xmrk flanking regions was surprising as positive cis-regulatory elements mediating a strong transcriptional activation in melanoma cells were expected based on the endogenous xmrk expression pattern.

To search for pigment cell specific transcriptional control elements in the xmrkB 5′ region upstream of the proximal 9.3 kb so far analyzed, a set of BAC reporter constructs containing between 67 kb and 9.3 kb xmrkB 5′ flanking sequences was generated (Fig. 5A) and transcriptional activity was quantified. To be able to correlate the data from the conventional plasmid based reporter assays with the results obtained using BAC derived reporter constructs, the 9.3 kb xmrkB promoter fragment (−9273/+61) was analyzed in both systems. In A2 cells, the stepwise deletion of promoter sequences located between 67 kb and 9.3 kb upstream of the TSS of xmrkB did not lead to any significant change in promoter activity (Fig. 5E), whereas a decrease was detected in the melanoma cell line PSM (Fig. 5D). In this cell line, sequences located between 28 kb and 67 kb upstream of xmrkB significantly increased transcriptional activity (p = 0.0008), indicating the presence of one or several potential pigment cell specific distal enhancer elements in this region. The putative enhancer element(s) led to a 2.1 fold increased transcriptional activity in the melanoma cell line PSM. However, to explain the massive overexpression of endogenous xmrkB transcripts found in Xiphophorus melanoma tissues and in the PSM cell line (Fig. 2B), a much stronger pigment cell specific transcriptional activation has to be expected. As no additional pigment cell specific cis-regulatory elements were detected in xmrkB flanking regions, it has to be concluded that the in vitro activity of the BAC derived reporter constructs does not completely reproduce the endogenous xmrkB expression pattern.

3.4 BAC derived reporter constructs do not reveal transcriptional differences between xmrkA and xmrkB

Several alleles of the xmrk oncogene have been identified in Xiphophorus, which show differences in their potential to induce tumor formation in backcross hybrids. The mdlSd-xmrkB allele, which was used for the luciferase experiments outlined above, is highly tumorigenic and induces development of malignant melanomas in R-free backcross hybrids with almost 100% penetrance. The mdlSr-xmrkA allele, in contrast, has a much lower tumorigenic potential and leads only to a mild hyperpigmentation in hybrid crosses. Besides structural differences in the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions, sequence variations in the coding sequence were noted between the two alleles (Adam et al., 1991; Volff et al., 2003). However, as the two mutations leading to constitutive activation of the Xmrk protein are present in both alleles, the XmrkA protein is considered to be equally tumorigenic as the XmrkB protein. By performing a comparative expression analysis we have demonstrated previously that the two xmrk alleles are differentially regulated on the transcriptional level, which strongly indicated that sequence variations in the regulatory regions are responsible for the low tumorigenic potential of xmrkA compared to xmrkB (Regneri and Schartl, 2012).

To find a possible mechanism for the expression differences between mdlSr-xmrkA and mdlSd-xmrkB, we compared the transcriptional activity of the full length xmrkB BAC reporter construct with the activity of an xmrkA BAC reporter construct in cells of melanoma and non-melanoma origin. As reference, we additionally included a BAC reporter construct for the proto-oncogene egfrb in the analysis (Fig. 6A). Contrary to xmrk, which is highly overexpressed in the melanoma cell line PSM (Fig. 2B), the proto-oncogene egfrb was transcribed on a high level in the epithelial-like cell line A2, whereas endogenous expression in PSM cells was hardly detectable by qPCR analysis (Fig. 2C). In line with this, a relatively high transcriptional activity of the BAC reporter construct containing the proto-oncogene egfrb was recorded in A2 cells, whereas the transcriptional activity of both xmrk reporter constructs was significantly lower in this cell line (p = 0.0203 and p = 0.0288 for xmrkB and xmrkA, respectively) (Fig. 6C). As A2 cells are a non-pigment cell line, the weaker transcriptional activation of both xmrk BAC reporter constructs was expected. In the melanoma cell line PSM, both xmrk BAC reporter constructs showed a slightly higher transcriptional activity than the reporter construct containing the proto-oncogene egfrb (p = 0.0126 and p = 0.0069 for xmrkB and xmrkA, respectively) (Fig. 6B). However, the differences in the transcription strength between xmrk and egfrb reporter constructs were much below what was expected from qPCR based expression studies in Xiphophorus melanoma tissues and the melanoma cell line PSM, where high levels of xmrk transcripts were found (Fig. 2B) and expression of egfrb was hardly detectable (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the xmrkA and xmrkB BAC reporter constructs showed a comparable transcriptional activity not only in the control cell line A2 (Fig. 6C), but also in the melanoma cell line PSM (Fig. 6B). This was unexpected as the data from the expression study suggested that only the highly tumorigenic xmrkB allele is transcriptionally activated in melanoma cells, whereas transcription of the non-tumorigenic xmrkA allele is not influenced by crossing-conditioned elimination of R (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). Hence, a significantly higher transcriptional activity of the xmrkB than of the xmrkA reporter construct was expected in the melanoma cell line PSM. In essence, we could not reproduce the transcriptional differences between the two xmrk alleles in reporter gene assays. An overview of expected and observed in vitro activities of xmrk reporter constructs in the different Xiphophorus cell lines is depicted in Table 1.

Figure 6. Transcriptional activity of xmrkB, xmrkA and egfrb BAC reporter constructs in Xiphophorus melanoma and non-melanoma cells.

(A) Schematic drawing of the full length xmrkB, xmrkA and egfrb BAC reporter constructs (BAC-xmrkB-LUC+, BAC-xmrkA-LUC+ and BAC-egfrb-LUC+). The BAC derived reporter constructs were generated by inserting the firefly luciferase gene luc+ together with a selection marker at the translational start site of xmrk or egfrb. Transcriptional activity of reporter constructs was measured in (B) the Xiphophorus melanoma cell line PSM and (C) the X. hellerii embryonic epithelial cell line A2. For normalization, a BAC reporter construct containing the renilla luciferase gene Rluc under control of the CMV promoter (BAC-RLUC) was cotransfected.

Taken together, our study shows that the in vitro activity of reporter constructs fails to reproduce the endogenous transcriptional regulation of the xmrk oncogene, indicating that additional regulatory mechanisms (e.g. epigenetic control of transcription) might be crucial.

4. Discussion

There is accumulating evidence demonstrating that overexpression of the xmrk oncogene in pigment cells is causative for melanoma development in Xiphophorus hybrids. In vitro, high expression levels of xmrk are sufficient to transform not only melanocytes, but a variety of other cell types as well, if xmrk is under control of ubiquitously active promoters (Leikam et al., 2008; Meierjohann et al., 2006b; Morcinek et al., 2002; Wellbrock et al., 1998). In transgenic fish models, ubiquitous expression of xmrk leads to tumorous growth of several tissues (Dimitrijevic et al., 1998; Winkler et al., 1994; Winnemoeller et al., 2005), while a liver specific promoter system confers development of hepatocellular carcinoma (Li et al., 2012) and the pigment cell specific mitfa promoter induces exclusively pigment cell tumors in vivo (Schartl et al., 2009). Detailed expression studies in the Xiphophorus system finally pointed out that upregulation of xmrk expression specifically in pigment cells of hybrids is the initiating event of melanomagenesis and that xmrk alleles that are not upregulated in hybrids fail to induce malignancies (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). One major mechanism of cell type specific gene expression is the regulation of transcription through cis-acting regulatory elements and their respective trans-acting factors. Disruption or interference with physiological transcription factor regulation of promoters is a frequent phenomenon underlying tumor development. Consequently, based on the melanocyte specificity of the oncogenic overexpression of xmrk, a pigment cell specific promoter region was postulated for xmrk, the activity of which is controlled directly or indirectly by the R locus encoded gene. In order to contribute to a better understanding of expression control of the oncogene, we functionally analyzed the entire putative gene regulatory region of the tumorigenic xmrkB allele. As the regular primary approach to search for pigment cell specific cis-regulatory elements, luciferase reporter assays were performed in melanoma versus control cells.

In the proximal xmrkB promoter region, we identified at least one positive cis-regulatory element located within 110 bp upstream of the transcription start site. This element mediated transcriptional activation in a non-cell type specific manner. In this region, an activating GC box element identical to the consensus binding site for the transcription factor Sp1 was described earlier (Baudler et al., 1997). Sp1 is a ubiquitously expressed nuclear transcription factor which binds to GC-rich motifs with high affinity (Kadonaga et al., 1987). Initially, Sp1 was thought to serve mainly as constitutive activator of so called housekeeping genes, which show a broad expression pattern. Housekeeping genes primarily use TATA-less, GC-rich promoters (Zhu et al., 2008) and transcriptional activation of such genes in reporter gene assays was found to be mediated mainly by proximal promoter regions containing multiple Sp1 consensus binding sites (Hayashi et al., 1998; Liedtke et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2012; Yamabe et al., 1998). To date, it is clear that Sp1 also contributes to the cell type specific transcriptional regulation of genes involved in differentiation and developmental processes (Gilmour et al., 2014; Morris and Taylor-Papadimitriou, 2001; Opitz and Rustgi, 2000). Moreover, Sp1 was found to be overexpressed in many cancers, which is positively correlated with progression of the disease (Chiefari et al., 2002; Guan et al., 2012). Hence, a role for Sp1 in inducing pigment cell specific transcriptional activation of xmrkB is conceivable. However, the finding that the respective promoter region showed no cell type specificity renders this reasoning less likely. Moreover, the GC box element is present at the same position in the proximal promoter region of the non-tumorigenic mdlSr-xmrkA allele (data not shown), which is not transcriptionally activated in melanocytes of R-free backcross hybrids. Taken together, this rather hints at a role for Sp1 (and other potential trans-acting factors also binding to this region) in driving high level expression of xmrk, but in a ubiquitous manner. In case of xmrkB, such a situation would then call for a silencing mechanism that prevents Sp1 action in all cells except melanocytes of R-free backcross hybrids. However, our reporter gene analyses provided no evidence for a classical transcriptional silencer in the xmrkB flanking regions that could account for such a mechanism. Alternatively, non-transcription factor based regulatory mechanism such as epigenetic control of gene expression could mediate transcriptional repression in these cells.

In PSM cells, only one other positive cis-regulatory element was identified within the 200 kb xmrkB flanking sequences. This putative enhancer element in the region between 28 kb and 67 kb upstream of the xmrkB TSS was evident exclusively in the melanoma cell line PSM and thus showed pigment cell specificity. However, deletion of this element decreased transcriptional strength only by 2.1 fold. Consequently, this element cannot account for the massive overexpression of endogenous xmrk transcripts found in the melanoma cell line PSM and in Xiphophorus melanomas. From this it has to be concluded that xmrkB flanking sequences in reporter gene assays fail to represent pigment cell specific overexpression comparable to the endogenous situation. There are several possible explanations for this unexpected finding:

First, it might be possible that important regulatory elements are missing from the reporter constructs. Hypothetically, this could result in incomplete transcriptional activation of xmrkB reporter constructs in melanoma cells. Distant cis-regulatory elements have been found for mammalian genes, but even those are mostly within 100 kb of the proximal promoter and only contribute to the refinement of transcriptional control (Visel et al., 2009) rather than to the all or nothing expression levels as seen for xmrk pigment cell specific regulation. Of note, the BACs that we used encompass not only xmrk but also flanking genes, which indicates that indeed the entire xmrk locus is covered by those BACs. In addition, the Xiphophorus genome is a typical representative of the more compact genomes of fish (Schartl et al., 2013), making it most probable that all relevant sequences were included in our constructs. On the other hand, we can by no means exclude this possibility.

Second, an unspecific activation of xmrk promoter sequences in the control cell line could be the reason for this failure. A2 cells, which are derived from X. hellerii, do not contain xmrk and the regulator locus R. Hypothetically, the lack of R mediated inhibition could lead to an unspecific activation of xmrk reporter constructs in these cells. However, detailed expression studies in Xiphophorus tissues clearly demonstrated that transcription of xmrk in non-pigment cells is not influenced by elimination of the regulator locus R and transcript levels remain on the same low background level in R-free backcross hybrids as in wildtype platyfish (Regneri and Schartl, 2012).

Hypothetically, this failure could also be due to a general inability of the cell lines used in this study to faithfully reproduce pigment cell specific transcription regulation. To exclude this possibility, we analyzed promoter sequences of the pigment cell specific mitfa gene in the same luciferase assay systems as for xmrkB. Using mitfa upstream sequences, a melanoma cell specific transcriptional activation was observed. The melanocyte specific expression of MITF-M, the human ortholog of mitfa, is driven by combinatorial binding of transcription factors (some of which are restricted to neural crest derived cells), to cis-regulatory elements in the proximal promoter region of the gene (Hartman and Czyz, 2015; Levy et al., 2006). Such promoters of high complexity are characteristic for tissue specific genes, which depend predominantly on proximal cis-regulatory modules for regulation (Lenhard et al., 2012). Considering that our test system is indeed able to reliably monitor cell type specific regulatory sequences, the failure to find such sequences in the xmrkB genomic locus strongly suggests the melanocyte specific transcription of xmrk to be not, as previously assumed, mainly driven by binding of pigment cell specific transcription factors to regulatory regions. Moreover, this hints at additional regulatory mechanism which cannot be reproduced in the reporter gene assay performed in this study.

Post-transcriptional control of gene expression could be such an additionally regulatory mechanism. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally via mRNA degradation or translational repression (Bartel, 2004). In humans, up to 60% of all protein-coding genes are predicted to be regulated by miRNAs (Friedman et al., 2009) and deregulated expression of miRNAs has been implicated in the development of many cancers including melanoma (Kozubek et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2014). Interestingly, a recent study has demonstrated deregulation of several melanoma associated miRNAs in Xiphophorus melanomas (Mishra et al., 2014). However, whether altered expression of miRNAs is involved in transcriptional deregulation of xmrk and thus is causative for melanoma development in Xiphophorus or if it is only a consequence of the xmrk induced transformation of the cell has not been addressed experimentally so far. The relative contributions of translational repression and target mRNA decay to miRNA mediated gene silencing in animals are still controversially discussed (Huntzinger and Izaurralde, 2011). Assuming a direct role for miRNAs in xmrk expression regulation by targeting the xmrk transcript itself, miRNA mediated gene silencing via target mRNA degradation has to be expected, because the clear correlation between the abundance of xmrk transcripts and melanoma development cannot be explained by translational repression alone. Alternatively, miRNAs could contribute to xmrk expression regulation by targeting upstream activator or modifier genes such as transcription factors and their cofactors. However, in this case the miRNAs would act on the level of xmrk transcriptional control and consequently their impact on xmrk promoter activity should be faithfully reproduced in the luciferase assays performed in this study.

Another potential regulatory mechanism is epigenetic control of gene expression. Interestingly, Altschmied et al. presented evidence for a role of DNA methylation changes in transcriptional activation of xmrk in melanoma cells. The proximal promoter region of xmrk was shown to be highly methylated in healthy tissues of purebred X. maculatus and tumor-bearing backcross hybrids (Altschmied et al., 1997), where xmrk is transcribed only on low background levels. A high methylation level was also found in gills, where xmrk expression is higher than in all other non-transformed tissues, but still considerably lower than in melanoma tissues (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). In contrast, the proximal promoter was completely demethylated in PSM cells and in a subpopulation of cells from melanoma tissues, which is consistent with high level overexpression of xmrk exclusively in Xiphophorus melanomas. However, the cloned DNA sequences, which we used in the reporter gene assays, are not expected to be modified by the epigenetic machinery of the transfected cell. A reasonable hypothesis to explain the anomalous transcriptional regulation found in the in vitro assays is therefore the absence of endogenous DNA methylation patterns in xmrkB reporter constructs.

Differences in epigenetic modifications might also represent a mechanism for the differential transcriptional regulation of mdlSd-xmrkB and mdlSr-xmrkA in pigment cells (Regneri and Schartl, 2012). The whole genomic region that harbors xmrk is a hotspot for transposon integrations and thus, xmrk is encircled by diverse categories of transposable elements, other repetitive sequences and pseudogenes (Froschauer et al., 2001; Volff et al., 2003). While most of these elements are present at the same position in the xmrkA and xmrkB flanking regions, some elements, like for example a piggyBac-like insertion in the proximal xmrk 5′ flanking region, were shown to be allele specific (Volff et al., 2003). Hence, as (retro)transposons are targeted and often silenced by the epigenetic machinery of the host cell (Levin and Moran, 2011; Rigal and Mathieu, 2011), transposable element induced epigenetic variations leading to transcriptional differences between the two alleles are conceivable. In that case, the unexpected finding that xmrkA and xmrkB BAC reporter constructs show a comparable transcriptional activity in the melanoma cell line PSM could be explained by the absence of such epigenetic modifications in the transiently transfected BAC DNA. This hypothesis is further supported by rare cases of sporadic melanoma formation in backcross hybrids carrying the non-tumorigenic mdlSr-xmrkA allele, which are normally not cancer prone. Since melanoma formation in these fish is paralleled by high xmrkA mRNA and protein expression levels (Regneri and Schartl, 2012), somatic mutations in the xmrkA promoter region or alterations in epigenetic modifications leading to transcriptional activation have been suggested as reason for sporadic xmrkA induced melanoma formation. However, given the relatively high incidence of such melanoma - approximately 1% - the latter possibility seems to be more likely. Transcriptional activation of xmrk due to environmental influences has also been suggested as reason for sporadic melanoma formation in purebred wildtype X. variatus (with mdlPu2-xmrkC) and X. cortezi (with mdlSc-xmrkD) (Fernandez and Morris, 2008; Schartl et al., 1995), which also exceed in frequency the expectations for the occurrence of spontaneous mutations.

Interestingly, differences in the DNA methylation status between melanoma cells and healthy tissues were not only shown for the xmrk oncogene, but also detected in the proximal promoter region of the proto-oncogene egfrb (Altschmied et al., 1997). In the melanoma cell line PSM, the egfrb promoter region was found to be highly methylated, which is in line with low endogenous egfrb transcript levels in these cells. In contrast, the egfrb BAC reporter construct showed a robust transcriptional activity in PSM cells. The clear discrepancy between the in vitro activity of the egfrb reporter construct and the endogenous transcript levels of the proto-oncogene indicates that transcriptional regulation of egfrb, like xmrkB expression, might depend, at least to some extent, on the endogenous DNA methylation pattern. For EGFR, the human ortholog of xmrk and egfrb, promoter hypermethylation has been demonstrated in several solid tumors and cancer cells lines, which was associated with gene silencing (Montero et al., 2006; Scartozzi et al., 2011). Moreover, a significant correlation between promoter demethylation and EGFR overexpression was found in BRAF inhibitor resistant human melanoma cells (Wang et al., 2015). This strongly suggests that epigenetic regulation via DNA methylation is crucial for controlling EGFR transcription. Consequently, a key role for epigenetic regulation in transcriptional activation of xmrk and thereby melanoma development in Xiphophorus is conceivable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Martina Regensburger for technical support and Barbara Klotz for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R24OD018555, subaward number 215420C.

Footnotes

This paper is based on a presentation given at the 7th Aquatic Animal Models of Human Disease Conference, hosted by Texas State University (December 13 - December 19, 2014).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam D, Dimitrijevic N, Schartl M. Tumor suppression in Xiphophorus by an accidentally acquired promoter. Science. 1993;259:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.8430335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam D, Maueler W, Schartl M. Transcriptional activation of the melanoma inducing Xmrk oncogene in Xiphophorus. Oncogene. 1991;6:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja MR, Anders F. A Genetic Concept of the Origin of Cancer, based in Part upon Studies of Neoplasms. Fish Prog Exptl Tumor Res. 1976;20:380–397. doi: 10.1159/000398712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschmied J, Ditzel L, Schartl M. Hypomethylation of the Xmrk oncogene promoter in melanoma cells of Xiphophorus. Biol Chem. 1997;378:1457–1466. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.12.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschmied J, Duschl J. Set of optimized luciferase reporter gene plasmids compatible with widely used CAT vectors. Biotechniques. 1997;23:436–438. doi: 10.2144/97233bm19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschmied J, Volff JN, Winkler C, Gutbrod H, Körting C, Pagany M, Schartl M. Primary structure and expression of the Xiphophorus DNA-(cytosine-5)-methyltransferase XDNMT-1. Gene. 2000;249:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatruda JF, Patton EE. Genetic models of cancer in zebrafish. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;271:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GS, Williams DE, Hendricks JD. Fish models for environmental carcinogenesis: the rainbow trout. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 1):5–21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudler M, Duschl J, Winkler C, Schartl M, Altschmied J. Activation of transcription of the melanoma inducing Xmrk oncogene by a GC box element. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:131–137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiefari E, Brunetti A, Arturi F, Bidart JM, Russo D, Schlumberger M, Filetti S. Increased expression of AP2 and Sp1 transcription factors in human thyroid tumors: a role in NIS expression regulation? BMC Cancer. 2002;2:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevic N, Winkler C, Wellbrock C, Gomez A, Duschl J, Altschmied J, Schartl M. Activation of the Xmrk proto-oncogene of Xiphophorus by overexpression and mutational alterations. Oncogene. 1998;16:1681–1690. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AA, Morris MR. Mate choice for more melanin as a mechanism to maintain a functional oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13503–13507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803851105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froschauer A, Körting C, Bernhardt W, Nanda I, Schmid M, Schartl M, Volff JN. Genomic plasticity and melanoma formation in the fish Xiphophorus. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2001;3:S72–80. doi: 10.1007/s10126-001-0049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froschauer A, Körting C, Katagiri T, Aoki T, Asakawa S, Shimizu N, Schartl M, Volff JN. Construction and initial analysis of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) contigs from the sex-determining region of the platyfish Xiphophorus maculatus. Gene. 2002;295:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour J, Assi SA, Jaegle U, Kulu D, van de Werken H, Clarke D, Westhead DR, Philipsen S, Bonifer C. A crucial role for the ubiquitously expressed transcription factor Sp1 at early stages of hematopoietic specification. Development. 2014;141:2391–2401. doi: 10.1242/dev.106054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A, Wellbrock C, Gutbrod H, Dimitrijevic N, Schartl M. Ligand-independent dimerization and activation of the oncogenic Xmrk receptor by two mutations in the extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3333–3340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. The genetics of viviparous top-minnow Platypoecilus: the inheritance of two kinds of melanophores. Genetics. 1927;12:253–283. doi: 10.1093/genetics/12.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H, Cai J, Zhang N, Wu J, Yuan J, Li J, Li M. Sp1 is upregulated in human glioma, promotes MMP-2-mediated cell invasion and predicts poor clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:593–601. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman ML, Czyz M. MITF in melanoma: mechanisms behind its expression and activity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1249–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1791-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häussler G. Über Melanombildungen bei Bastarden von Xiphophorus maculatus var. rubra. Klin Wochenschr. 1928;7:1561–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Usui M, Nishioka J, Zhang ZX, Suzuki K. Regulation of the human protein C inhibitor gene expression in HepG2 cells: role of Sp1 and AP2. Biochem J. 1998;332 (Pt 2):573–582. doi: 10.1042/bj3320573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrbek T, Seckinger J, Meyer A. A phylogenetic and biogeographic perspective on the evolution of poeciliid fishes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;43:986–998. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L, Zon LI. Zebrafish as a model for normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:433–438. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadonaga JT, Carner KR, Masiarz FR, Tjian R. Isolation of cDNA encoding transcription factor Sp1 and functional analysis of the DNA binding domain. Cell. 1987;51:1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosswig C. Über Kreuzungen zwischen den Teleostiern Xiphophorus helleri und Platypoecilus maculatus. Z Indukt Abstammungs-Vererbungsl. 1928;47:150– 158. [Google Scholar]

- Kozubek J, Ma Z, Fleming E, Duggan T, Wu R, Shin DG, Dadras SS. In-depth characterization of microRNA transcriptome in melanoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, Vielkind U, Anders F. Cell cultures derived from embryos and melanoma of poeciliid fish. In Vitro. 1979;15:537–544. doi: 10.1007/BF02618156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leikam C, Hufnagel A, Schartl M, Meierjohann S. Oncogene activation in melanocytes links reactive oxygen to multinucleated phenotype and senescence. Oncogene. 2008;27:7070–7082. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard B, Sandelin A, Carninci P. Metazoan promoters: emerging characteristics and insights into transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrg3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HL, Moran JV. Dynamic interactions between transposable elements and their hosts. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:615–627. doi: 10.1038/nrg3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Huang X, Zhan H, Zeng Z, Li C, Spitsbergen JM, Meierjohann S, Schartl M, Gong Z. Inducible and repressable oncogene-addicted hepatocellular carcinoma in Tet-on xmrk transgenic zebrafish. J Hepatol. 2012;56:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke C, Groger N, Manns MP, Trautwein C. The human caspase-8 promoter sustains basal activity through SP1 and ETS-like transcription factors and can be up-regulated by a p53-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27593–27604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Weber CE, Osen W, Bosserhoff AK, Eichmuller SB. The role of microRNAs in melanoma. Eur J Cell Biol. 2014;93:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maston GA, Evans SK, Green MR. Transcriptional regulatory elements in the human genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:29–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäueler W, Schartl A, Schartl M. Different expression patterns of oncogenes and proto-oncogenes in hereditary and carcinogen-induced tumors of Xiphophorus. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:288–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierjohann S, Müller T, Schartl M, Bühner M. A structural model of the extracellular domain of the oncogenic EGFR variant Xmrk. Zebrafish. 2006a;3:359–369. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2006.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierjohann S, Schartl M. From Mendelian to molecular genetics: the Xiphophorus melanoma model. Trends Genet. 2006;22:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierjohann S, Wende E, Kraiss A, Wellbrock C, Schartl M. The oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor variant Xiphophorus melanoma receptor kinase induces motility in melanocytes by modulation of focal adhesions. Cancer Res. 2006b;66:3145–3152. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele A, Dekker J. Long-range chromosomal interactions and gene regulation. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:1046–1057. doi: 10.1039/b803580f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RR, Kneitz S, Schartl M. Comparative analysis of melanoma deregulated miRNAs in the medaka and Xiphophorus pigment cell cancer models. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;163:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero AJ, Diaz-Montero CM, Mao L, Youssef EM, Estecio M, Shen L, Issa JP. Epigenetic inactivation of EGFR by CpG island hypermethylation in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1494–1501. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.11.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcinek JC, Weisser C, Geissinger E, Schartl M, Wellbrock C. Activation of STAT5 triggers proliferation and contributes to anti-apoptotic signalling mediated by the oncogenic Xmrk kinase. Oncogene. 2002;21:1668–1678. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JR, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. The Sp1 transcription factor regulates cell type-specific transcription of MUC1. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:133–139. doi: 10.1089/104454901300068942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Saito D, Tanaka M. Generation of transgenic medaka using modified bacterial artificial chromosome. Development, Growth & Differentiation. 2008;50:415–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz OG, Rustgi AK. Interaction between Sp1 and cell cycle regulatory proteins is important in transactivation of a differentiation-related gene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2825–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Mitchell DL, Nairn RS. Genetic and environmental melanoma models in fish. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:314–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regneri J, Schartl M. Expression regulation triggers oncogenicity of xmrk alleles in the Xiphophorus melanoma system. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;155:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigal M, Mathieu O. A “mille-feuille” of silencing: epigenetic control of transposable elements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scartozzi M, Bearzi I, Mandolesi A, Giampieri R, Faloppi L, Galizia E, Loupakis F, Zaniboni A, Zorzi F, Biscotti T, Labianca R, Falcone A, Cascinu S. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene promoter methylation and cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1786–1790. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl A, Malitschek B, Kazianis S, Borowsky R, Schartl M. Spontaneous melanoma formation in nonhybrid Xiphophorus. Cancer Res. 1995;55:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M. Platyfish and swordtails: a genetic system for the analysis of molecular mechanisms in tumor formation. Trends Genet. 1995;11:185–189. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M. Beyond the zebrafish: diverse fish species for modeling human disease. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:181–192. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M, Meierjohann S. Oncogenetics. In: Pilastro A, Evans J, Schlupp I, editors. Evolution and Ecology of Poeciliid Fishes. University of Chicago Press; 2010. pp. 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M, Walter RB, Shen Y, Garcia T, Catchen J, Amores A, Braasch I, Chalopin D, Volff J-N, Lesch K-P, Bisazza A, Minx P, Hillier L, Wilson RK, Fuerstenberg S, Boore J, Searle S, Postlethwait JH, Warren WC. The genome of the platyfish, Xiphophorus maculatus, provides insights into evolutionary adaptation and several complex traits. Nat Genet. 2013;45:567–572. doi: 10.1038/ng.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M, Wilde B, Laisney JA, Taniguchi Y, Takeda S, Meierjohann S. A mutated EGFR is sufficient to induce malignant melanoma with genetic background-dependent histopathologies. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:249–258. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schories S, Meyer MK, Schartl M. Description of Poecilia (Acanthophacelus) obscura n. sp., (Teleostei: Poeciliidae), a new guppy species from western Trinidad, with remarks on P. wingei and the status of the “Endler’s guppy”. Zootaxa. 2009:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Seo HC, Kube M, Edvardsen RB, Jensen MF, Beck A, Spriet E, Gorsky G, Thompson EM, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, Chourrout D. Miniature genome in the marine chordate Oikopleura dioica. Science. 2001;294:2506. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5551.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh DP, Bhargavan B, Chhunchha B, Kubo E, Kumar A, Fatma N. Transcriptional protein Sp1 regulates LEDGF transcription by directly interacting with its cis-elements in GC-rich region of TATA-less gene promoter. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]