Abstract

Background

Manual lesion delineation by an expert is the standard for lesion identification in MRI scans, but is time-consuming and can introduce subjective bias. Alternative methods often require multi-modal MRI data, user interaction, scans from a control population, and/or arbitrary statistical thresholding.

New Method

We present an approach for automatically identifying stroke lesions in individual T1-weighted MRI scans using naïve Bayes classification. Probabilistic tissue segmentation and image algebra were used to create feature maps encoding information about missing and abnormal tissue. Leave-one-case-out training and cross-validation was used to obtain out-of-sample predictions for each of 30 cases with left hemisphere stroke lesions.

Results

Our method correctly predicted lesion locations for 30/30 un-trained cases. Post-processing with smoothing (8mm FWHM) and cluster-extent thresholding (100 voxels) was found to improve performance.

Comparison with Existing Method

Quantitative evaluations of post-processed out-of-sample predictions on 30 cases revealed high spatial overlap (mean Dice similarity coefficient = 0.66) and volume agreement (mean percent volume difference = 28.91; Pearson’s r = 0.97) with manual lesion delineations.

Conclusions

Our automated approach agrees with manual tracing. It provides an alternative to automated methods that require multi-modal MRI data, additional control scans, or user interaction to achieve optimal performance. Our fully trained classifier has applications in neuroimaging and clinical contexts.

Keywords: Segmentation, chronic stroke, supervised learning, lesion-symptom mapping, T1-weighted MRI, naïve Bayes classification

1. Introduction

The study of deficits that follow damage to different brain regions has been a fundamental tool in cognitive neuroscience and neurology. Indeed, lesion-deficit analyses have allowed great insights into how specific structures of the brain relate to cognition and behavior (Bastian 1887; Berker et al. 1986; Dronkers et al. 2007; Turken and Dronkers 2011; Bonilha et al. 2014; Fridriksson et al. 2014; Corbetta et al. 2015). While early lesion-deficit studies relied on postmortem analyses, the advent of advanced neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has enabled researchers to study lesion-deficit relationships in vivo using methods such as voxel-lesion symptom mapping (VLSM) (Bates et al. 2003; Rorden et al. 2007, 2009; Chen and Herskovits 2010; Geva et al. 2012). Voxel-based computational approaches to lesion-deficit analyses require the precise and reliable definition of lesion-class voxels in order to enable strong inferences about structure-function relationships (Crinion et al. 2013), and typically utilize lesion masks that are hand-drawn by an expert rater. Despite its potential to introduce subjective bias (Fiez et al. 2000) and being very time intensive (Wilke et al., 2011), manual delineation by an expert remains the gold standard for lesion identification in MRI scans.

The drawbacks of manual delineation have motivated the development of automated and/or semi-automated approaches to identifying lesions in MRI scans. Early attempts at automatic lesion delineation included using voxel-based morphometry (VBM), a statistical technique for identifying regional abnormalities in tissue density/volume between populations, to identify abnormal voxels in individual T1-weighted (T1w) MRI scans (Gitelman et al. 2001). Although VBM may be capable of highlighting structural abnormalities that can facilitate lesion delineation by expert raters, it lacks the spatial resolution and statistical power to provide a true replacement for manual lesion delineation (Mehta et al. 2003).

More recently, methods combining probabilistic tissue segmentation with outlier-based fuzzy clustering principles have been proposed for automated (Seghier et al., 2008) and semi-automated (Wilke et al., 2011) lesion delineation in T1w scans. The method developed by Seghier and colleagues (2008) uses probabilistic tissue segmentations obtained from healthy control subjects to estimate mean grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) probabilities for each voxel. To identify lesions in patient scans, these estimates are then used to compute a metric quantifying each voxel’s membership to a fuzzy set within each tissue class; the resulting fuzzy set membership estimates for each tissue class are then combined and statistically thresholded to determine whether each voxel belongs to the lesion tissue class (ALI: automatic lesion identification; Seghier et al., 2008). Similarly, Wilke and colleagues (2011) developed a semi-automated algorithm that uses probabilistic tissue segmentation to construct a set of 4 feature maps encoding information about tissue composition, tissue homogeneity, shape, and laterality at each voxel. These feature maps are then used to construct robust z-score maps that are manually thresholded and combined by the user to provide the final lesion delineation (Wilke et al., 2011). A recent comparison of these methods with manual lesion delineation suggests that the semi-automated method may provide somewhat more reliable results, but at an average cost of 25 minutes per subject to complete the manual thresholding step (Wilke et al., 2011). The ALI method, while automated, also suffers the drawback of requiring scans from a group of healthy control subjects in order to identify voxels that can be defined as outliers on the group level and assigned to the lesioned tissue class (Seghier et al., 2008), making it unsuitable for situations where data from healthy control subjects is unavailable. Its performance might also be expected to vary depending on the healthy control scans used to estimate “normal” tissue probability values, complicating generalizations about optimal threshold choices. Both approaches require custom pre-processing and/or segmentation procedures (i.e. prior-less or modified segmentation with multiple iterations) that may complicate their implementation or increase the potential for user error. Both methods require arbitrary statistical thresholds that depend on either visual inspection for each case (Wilke et al., 2011) or the results from a small test sample with a specific control group (Seghier et al., 2008). Because neither of these methods has been validated on samples larger than 11 cases (Wilke et al., 2011), it is unclear how well they will generalize.

Supervised learning methods using ensemble classifiers such as random forests (Mitra et al., 2014) and extra-tree forests (Maier et al., 2014) have recently been proposed for automatically identifying stroke lesions in MRI scans. These methods provide attractive alternatives to the aforementioned fuzzy clustering approaches in that they do not require healthy control data, user interaction, or arbitrary threshold choices to obtain predicted lesion delineations for new cases. However, these approaches require data from multiple MRI modalities to achieve optimal performance (Maier et al., 2014; Mitra et al., 2014), and rely primarily on information provided by scans acquired using T2-weighted (T2w) fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and/or diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) sequences to identify lesion class voxels. Unfortunately, these methods may not be optimal for use in functional neuroimaging research settings where only a single anatomical scan (typically T1w) is typically acquired due to time and/or monetary constraints.

Here, we present a new supervised learning method for automatically delineating stroke lesions in single-patient T1w MRI volumes that employs naïve Bayes classification to identify lesion voxels based on information contained in strategically constructed feature maps. This method is fully automated, and does not require special pre-processing parameters or custom segmentation routines, as it requires only default SPM probabilistic tissue segmentation and normalization routine be performed prior to loading image volumes into the algorithm. Importantly, it also does not require scans from healthy controls, user interaction, or arbitrary statistical threshold determination for good performance. Here, we describe our method and validate it by comparing out-of-sample predicted lesion delineations for a large sample (N=30) of chronic stroke patients with heterogeneous lesion etiologies to manual lesion delineations by an expert rater.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects and imaging data

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions and were performed in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki ethics principles and principles of informed consent. After obtaining verbal and written consent, T1w MRI scans were acquired from 30 patients (19 male, 11 female) with left-hemisphere stroke of at least 6 months duration. Patient demographics and left-hemisphere lesion volumes are shown in Table 1. MRI data collection was performed at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Data collected at CCHMC were acquired on a 3.0 Tesla research-dedicated MRI system and consisted of high-resolution T1-weighted 3-dimensional anatomical MRI scans (TR/TE = 8.1 s/3.7 ms, FOV = 25.0×21.1×18.0 cm, matrix = 252×210, flip angle = 8 degrees, slice thickness = 1 mm). Data collected at the University of Alabama at Birmingham were acquired using a research dedicated 3.0 Tesla MR system and consisted of high-resolution T1-weighted 3-dimensional anatomical MRI scans (TR/TE = 2.0 s/2.17 ms, FOV = 24.0×24.0 cm, matrix = 256×256, flip angle = 9 degrees, slice thickness = 1 mm).

Table 1.

Case characteristics (N= 30)

| Mean | SD | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.0 | 12.13 | 52.0 | 23.0–78.0 |

|

Time since stroke (yrs) |

4.04 | 3.26 | 3.75 | 0.5–11.42 |

|

Lesion volume (voxels) |

30314.3 | 24989.95 | 25089.0 | 1485.0–87748.0 |

2.2 Tissue segmentation and normalization to template space

All MRI data preprocessing was performed using SPM12 (Wellcome Department, UCL, UK) running in MATLAB R2014b (The Mathworks, Nattick, USA). Probabilistic tissue segmentation, bias correction, and spatial normalization were achieved under the unified normalization framework (Ashburner and Friston 2005) using the New Segment tool implemented in SPM12. Unified normalization combines probabilistic tissue segmentation, bias correction, and spatial normalization in the inversion of a single model; model parameter estimation is accomplished by alternating among tissue classification, bias correction, and spatial registration steps to enable the modeling of conditional dependencies among model parameters (Ashburner and Friston, 2005). Both the Unified Segmentation (implemented in older versions of SPM) and New Segment (implemented in SPM8 and SPM12) procedures use Gaussian mixture modeling to model the intensity distributions for each tissue class, and incorporate spatial weighting in the form of grey mater (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) prior probability maps (PPMs). The New Segment procedure differs primarily in its treatment of mixing proportions, its expansion of PPMs for modeling out of brain voxels, and its implementation of an improved registration model (SPM 12 Manual, FIL Methods Group, UCL, UK). The unified normalization approach has been shown to provide good normalization for lesioned brains, even without the use of cost-function masking (Crinion et al. 2007; Ripollés et al. 2012). Thus, we employed the unified normalization approach using the New Segment tool implemented in SPM12 to obtain tissue probabilistic maps (TPMs) that encode estimated GM, WM, CSF, and non-brain tissue class probabilities for each voxel. The resulting GM/WM/CSF TPMs, along with the original T1w image volume, were then normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template space using the deformation fields provided by the New Segment tool. Finally, the both the GM/WM/CSF TPMs and the GM/WM/CSF PPMs were smoothed with 8mm full-width half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. The smoothed TPMs and PPMs were then used to create feature maps (see section 2.5).

2.3 Manual lesion delineation

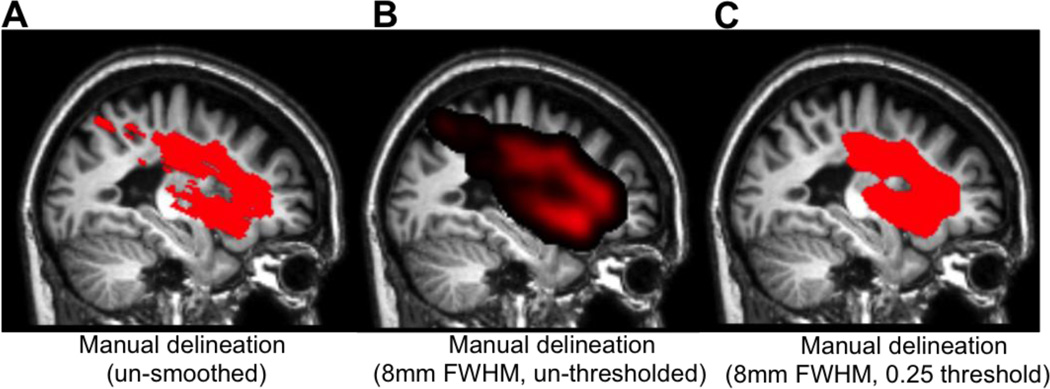

Manually delineated lesion masks were used as ground truth for classifier training and for assessing classification performance during cross-validation. Manual lesion delineation was performed by an experienced neuroanatomist (JPS), and consisted of hand-drawing the lesion boundary on consecutive axial slices from the native space T1w MRI scan of each case. These were then filled to create 3-dimensional lesion volumes using AFNI software (Cox 1996). The hand-drawn lesion masks for each case were normalized to MNI space using the deformation fields obtained from the unified normalization of the T1w anatomical volume for that case. The normalized binary lesion masks were then smoothed with an 8mm FWHM Gaussian kernel, and thresholded to retain only voxels with values greater than 0.25 (voxels very near the edge of the mask would be thresholded out because they were adjacent to many zero-value voxels). This step was performed to smooth over rough edges and discontinuities in the manually delineated masks that resulted from their being drawn on a slice-by-slice basis in order to reduce potential confounds for subsequent spatial similarity analyses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A. The un-smoothed manual lesion delineation is shown overlaid on sagittal slices from the corresponding case. B. The same manual lesion delineation is shown after being smoothed with an 8mm FWHM Gaussian kernel and C. thresholded to retain voxels with values greater than 0.25.

2.4 Gaussian naïve Bayes classification

Gaussian naïve Bayes (GNB) classification is a supervised learning algorithm that uses Bayes’ theorem as a framework for classifying observations into one of a pre-defined set of classes based on information provided by predictor variables. GNB classifiers estimate the conditional probabilities that an observation belongs to a particular class given the values of the predictor variables under the assumption that the predictor variables are class-conditionally independent, and thus (naively) do not take into account the covariance among the predictor variables. Thus, the posterior probability that an observation Y has class index k given the values of predictor variables X1,…,XP is modeled according to Bayes theorem as:

where π(Y = k) is the prior probability that the class index is k. For each predictor X1,…,Xp, the algorithm estimates a separate Gaussian distribution for each class, and observations are assigned to the class with the maximum posterior probability given the predictor values. GNB classifiers often outperform other, more complicated classifiers, and perform very well on classification tasks even when assumptions are not met (Domingos and Pazzani 1997; Rish et al. 2001; Zhang 2004, 2005), such as the classification of fMRI responses evoked by different task conditions (Raizada and Lee 2013). However, by separately modeling missing and abnormal tissue in our creation of feature maps (predictors), we aimed to avoid including highly redundant information in our predictor variables (Section 2.4.1).

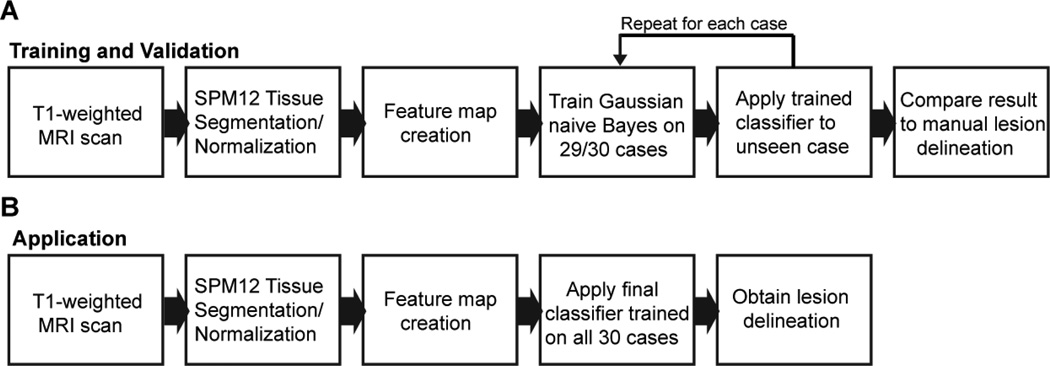

Here, we describe a new method for automatically delineating stroke lesions in individual T1-weighted MRI scans using GNB classification. We first used simple algebraic operations to separately model “missing” and “abnormal” lesion class voxels with the GM/WM/CSF TPMs/PPMs from the segmentation procedure. Then, during the supervised learning step, we trained and cross-validated the classifier using the feature maps as predictor variables and the manual lesion delineations as ground truth lesion class labels. The supervised learning step consisted of an iterative leave-one-case-out training and cross-validation procedure: for each of the 30 cases, a GNB classifier was trained on the other 29 cases, and the trained classifier was then used to predict the lesion delineation for the un-trained case. This provided an out-of-sample prediction for each of the 30 cases, allowing inferences about the generalizability of our classification method to un-trained cases. The resulting predicted lesion delineations were then compared to the corresponding manual lesion delineations on the basis of spatial similarity and volume agreement. This process is schematized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration outlining pre-processing and supervised learning procedure is shown in (A), and a schematic illustration outlining the application of the trained classifier for predicting lesion delineations for new cases is shown in (B).

2.4.1 Feature map creation

The image features encoded in each feature map were chosen to provide non-redundant information that would facilitate discrimination between lesion and non-lesion voxels by the classifier. For each case, feature maps were created using the smoothed GM/WM/CSF TPMs and the smoothed GM/WM/CSF PPMs. Prior to creating feature maps, the smoothed GM/WM/CSF TPMs were split into affected (in this case, left) and unaffected (in this case, right) hemispheres. The affected hemisphere TPMs were then mirrored into left-hemisphere space. The GM/WM/CSF PPMs were restricted to contain only voxels within the affected (in this case, left) hemisphere. The total intracranial volume mask included with SPM12 was used to exclude bounding box voxels.

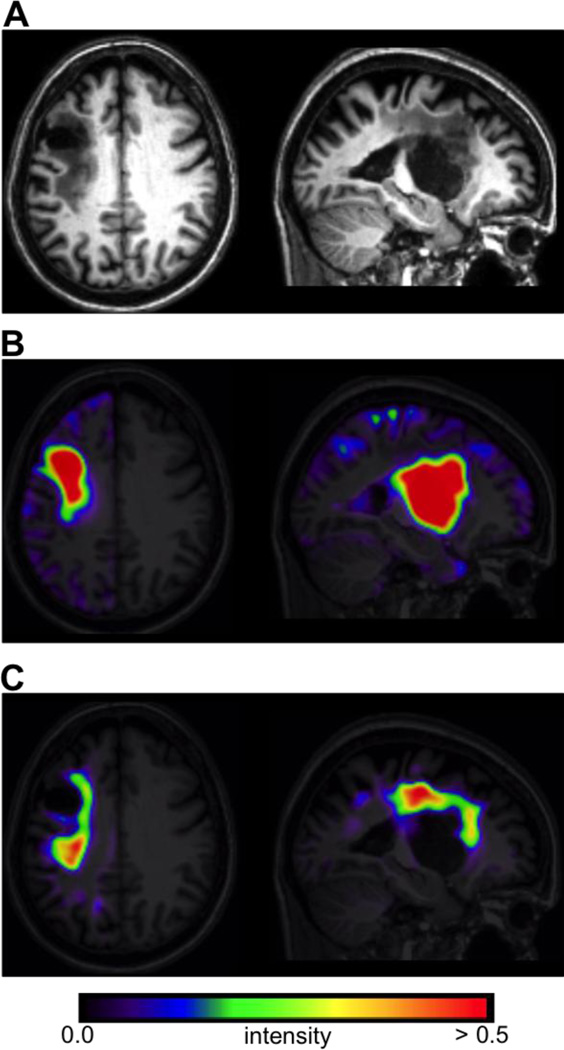

Separate feature maps were created to independently model lesion voxels corresponding to “missing” and “abnormal” tissue, where “missing” tissue corresponded primarily to the lesion core, and “abnormal” tissue corresponded to the remaining tissue primarily affected by gliosis (Fig. 3). The first feature map (referred to as F1) provided information about missing tissue, and was motivated by the fact that SPM segmentation typically classifies chronic stroke lesions as CSF due to missing tissue voxels being assigned low GM/WM probability values (Seghier et al. 2008; Wilke et al. 2009, 2011). For each voxel in the affected hemisphere, this feature map encoded positive values obtained from the average of 2 image volumes that were defined as:

-

(CSFAffected − CSFUnaffected) * ((GMUnaffected + WMUnaffected) − (GMAffected + WMAffected))

and

(CSFAffected − CSFPrior) * ((GMPrior + WMPrior) − (GMAffected + WMAffected)).

Thus, voxels with high intensities in F1 corresponded to voxels in the affected hemisphere that were classified as more likely to be CSF than would be expected based on the tissue probabilities observed for their counterparts in the unaffected hemisphere TPMs/PPMs, and that were also classified as less likely to be GM or WM than would be expected based on the tissue probabilities observed for their counterparts in the unaffected hemisphere TPMs/PPMs. The rationale for averaging each of the initial volumes to obtain the final feature map was that 1) using them as separate predictors would be sub-optimal since both volumes contain highly redundant information, as many of the “true” lesion voxels were expected to have high values in both volumes, and 2) averaging them retained the values of concordant voxels while reducing the values of voxels that had high values in only 1 volume (e.g. false positives due to inter-hemispheric or inter-individual variability). An example of this feature map for a single case is shown in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

A. Axial and sagittal slices from the normalized T1w scan for a single case. B. The “missing tissue” feature map F1 for the same case. C. The “abnormal tissue” feature map F2 for the same case.

The second feature map (referred to as F2) provided information about abnormal tissue, and was motivated by the fact that SPM segmentation often classifies these tissues as intact GM due to the T1w signal intensities being similar to that observed in healthy GM (Mehta et al. 2003). For each voxel in the affected hemisphere, this feature map encoded positive values obtained from averaging two image volumes defined as:

-

(GMAffected − GMUnaffected) * (WMUnaffected − WMAffected)

and

(GMAffected − GMPrior) * (WMPrior − WMAffected).

Thus, voxels with high intensities in F2 corresponded to voxels in the affected hemisphere that were classified as more likely to be GM than would be expected based on the tissue probabilities observed for their counterparts in the unaffected hemisphere and TPMs/PPMs, and that were also classified as less likely to be WM than would be expected based on the tissue probabilities observed for their counterparts in the unaffected hemisphere TPMs/PPMs. An example of this feature map is shown in Fig. 3C.

2.4.2 Supervised learning

Training and validation were accomplished using a leave-one-case-out cross-validation approach. This procedure consisted of iteratively leaving out a single case and training a GNB classifier on the remaining 29 cases. The trained classifier was then applied to the un-trained case, resulting in an out-of-sample prediction for the un-trained case. The default binarizing decision threshold of t = 0.5 was used to define posterior class labels. This procedure resulted in 30 out-of-sample predicted lesion delineations that were then compared to manual lesion delineations on the basis of spatial similarity and volume agreement. The leave-one-case-out cross-validation approach was chosen over alternative approaches such as k-fold cross-validation because it allowed us to obtain out-of-sample predicted lesion delineations for each case that could then be compared to manual lesion delineations.

2.5 Post-processing

To assess whether additional post-processing steps might improve overall performance, simple post-processing procedures were applied to the predicted lesion delineations. First, the binary-valued predicted lesion delineations were smoothed using an 8mm FWHM Gaussian kernel and thresholded to retain voxels with values above 0.25. This was identical to the smoothing applied to the manual lesion delineations (see Section 2.3), and allowed for the closing of gaps, smoothing of rough edges, and removal of small isolated voxel clusters in the predicted lesion delineations. Next, clusters containing less than 100 voxels were removed. Evaluation metrics for predicted lesion delineations with and without post-processing were compared to determine if post-processing improved lesion delineation.

2.5 Spatial similarity analyses

The degree of spatial similarity between the predicted lesion delineations and the manual lesion delineations was quantified using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) (Dice 1945). The DSC is a spatial overlap index, and the similarity coefficient between each predicted lesion delineation and the corresponding manual delineation was computed as

where the terms Predicted and Manual refer to the voxels with lesion class labels in each lesion delineation. The DSC ranges from 0 to 1, and incorporates information about both false positives and false negatives: the numerator is equivalent to twice the number of true positives, and the denominator is equivalent to twice the number of true positives plus the number of false positives and false negatives (Zou et al. 2004). The DSC was chosen for assessing spatial similarity between the predicted lesion delineations and the manual lesion delineations because it has been used in the validations of other recently published methods for lesion delineation (Seghier et al. 2008; Wilke et al. 2011; Maier et al. 2014; Mitra et al. 2014), and because it is straightforward to interpret. DSCs ranging between 0.6 and 0.8 have been previously reported as “good”, with values above 0.7 being reported as “high” for comparisons of manually delineated and automatically generated lesion masks (Seghier et al. 2008; Wilke et al. 2011). This interpretation was applied in our assessment of the validation results.

2.6 Volumetric analyses

The relationship between the predicted lesion volumes and ground truth lesion volumes obtained from manual delineation was first assessed using linear (Pearson’s) correlation analyses. A strong correlation would indicate that predicted lesion volumes mapped linearly to those obtained from the manual lesion delineations. This property is of particular importance for the application of our method by studies analyzing the relationship between lesion volume estimates and other variables, although it is important to note that linear correlation analyses do not provide information about the actual precision of the predicted volume estimates. For example, multiplying all of the predicted lesion volumes by a constant amount would not affect the strength of the linear correlation. For this reason, we also assessed the percent volume difference (PVD) between the predicted lesion volumes and the ground truth lesion volumes. PVD was calculated as , where abs indicates the absolute value operation, and Vmanual and Vpredicted indicate the volume of the manual and predicted lesion delineations, respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Spatial similarity analyses

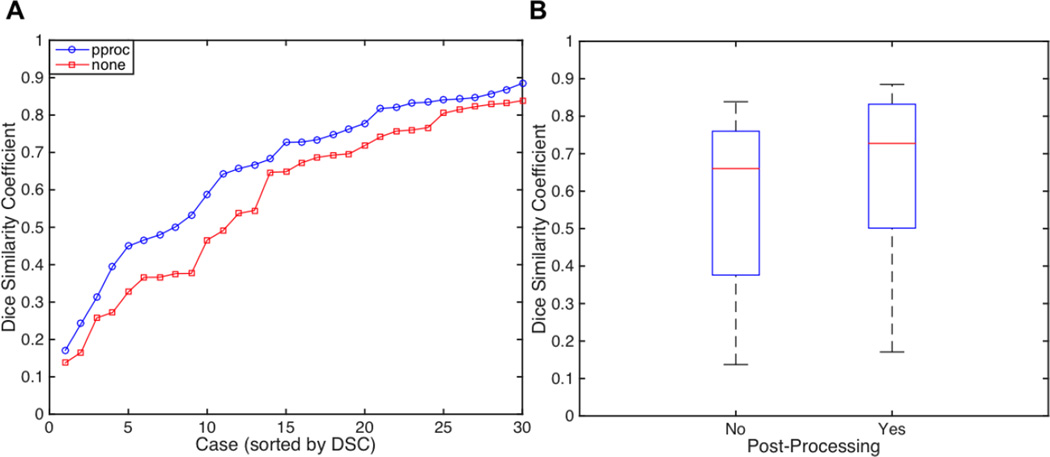

First, we compared DSC estimates between the predicted lesion delineations obtained from the leave-one-case-out cross-validation with and without post-processing. Descriptive statistics for DSCs obtained with and without post-processing are shown in Table 2, and plots are shown in Fig. 4. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test whether the median of the differences in DSCs between predicted lesion delineations with and without post-processing significantly differed from 0. Non-parametric statistics were used since the DSC has a bounded range of [0,1]. This test revealed that the median of the differences was significantly greater than 0 (p<0.001). Descriptive statistics shown in Table 3 indicate that DSCs were higher for the post-processed predicted lesion delineations. Plots of DSCs for raw and post-processed predicted lesion delineations are shown in Fig. 4. Of the 30 post-processed predicted lesion delineations, 20 (66.6%) had DSCs of at least 0.60, considered “good”. Of the remaining 10 cases, 3 had DSCs between 0.50 and 0.59, 4 had DSCs between 0.40 and 0.49, and 3 had DSCs between 0.17 and 0.31.

Table 2.

DSCs for all 30 cases with and without post-processing

| Post-processing | Mean | SD | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.66 | 0.14–0.84 |

| Yes | 0.66 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.17–0.89 |

Figure 4.

A. Plots of Dice similarity coefficients (DSCs) for all 30 predicted lesion delineations without (red) and with (blue) post-processing. B. Boxplots of DSCs for all 30 predicted lesion delineations with and without post-processing.

Table 3.

PVDs for all 30 cases with and without post-processing

| Post-processing | Mean | SD | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 30.56 | 24.29 | 24.73 | 2.52–119.25 |

| Yes | 28.91 | 24.54 | 22.36 | 0.26–91.38 |

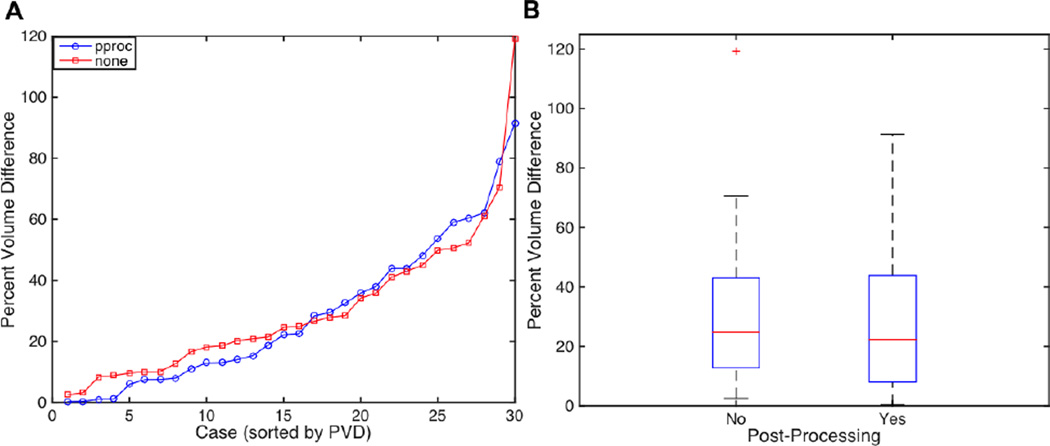

3.2 Volumetric analyses

We first assessed the Pearson linear correlation between lesion volume estimates obtained from each method. This revealed a very strong linear relationship (Pearson’s r) between lesion volume estimates obtained from the ground truth manual lesion delineations and the predicted lesion delineations without post-processing (r = 0.97, p < 0.001) and with post-processing (r = 0.97, p < 0.001). Next, we calculated the PVD between lesion volume estimates obtained from each method. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test whether the median of the differences in PVDs for predicted lesion delineations with and without post-processing significantly differed from 0. This test revealed that the median of the differences did not differ from 0 (p=0.36). Descriptive statistics shown in Table 3 indicate that PVDs were somewhat lower with post- processing. Plots of PVDs are shown in Fig. 5. Of all 30 post-processed predicted lesion delineations, 24 (80%) had PVDs of less than 50%.

Figure 5.

Plots of Percent volume differences (PVDs) for all 30 predicted lesion delineations without (red) and with (blue) post-processing. B. Boxplots of PVDs for all 30 predicted lesion delineations with and without post-processing.

3.3 Comparison between cases with large vs. small lesions

Automated and semi-automated approaches for T1w lesion delineation have been previously reported to show biases for large lesions (Wilke et al., 2011). While this is likely, in part, due to the use of the DSC as an evaluation metric, it is biased by target prevalence and thus more harshly penalizes errors for cases with lower target class frequencies (Zou et al. 2004). Thus, we decided to assess the effect of lesion size on our evaluation metrics. Since the postprocessing predicted lesion delineations obtained significantly better DSCs and somewhat lower PVDs than those without post-processing, further analyses were performed using the post-processed predicted lesion delineations.

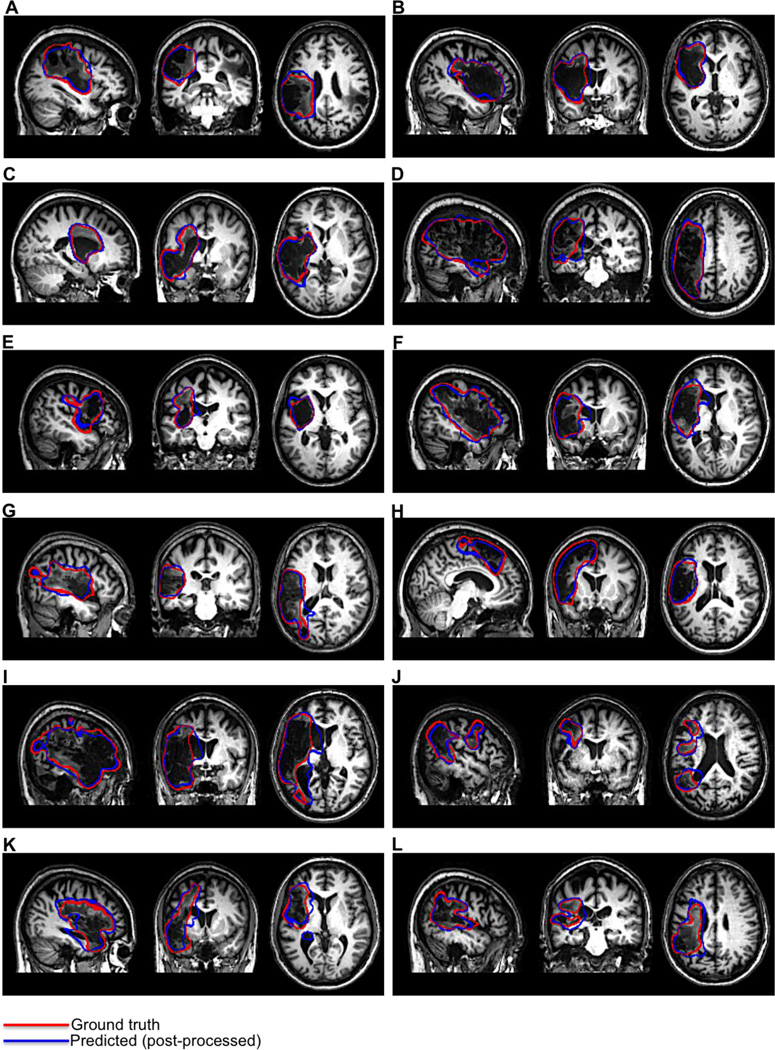

To assess whether median DSCs differed significantly between cases with large vs. small lesions, a median split by lesion volume (obtained from the manual delineation; median = 25,089 voxels) was performed on the post-processed predicted lesion delineations. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to test whether median DSCs differed between the groups. This revealed that the median DSC was significantly higher for the large lesion group (p < 0.001). Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

DSCs for predicted lesion delineations (post-processed) by group

| Group | Mean | SD | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large (15) | 0.81 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.73–0.89 |

| Small (15) | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.17–0.73 |

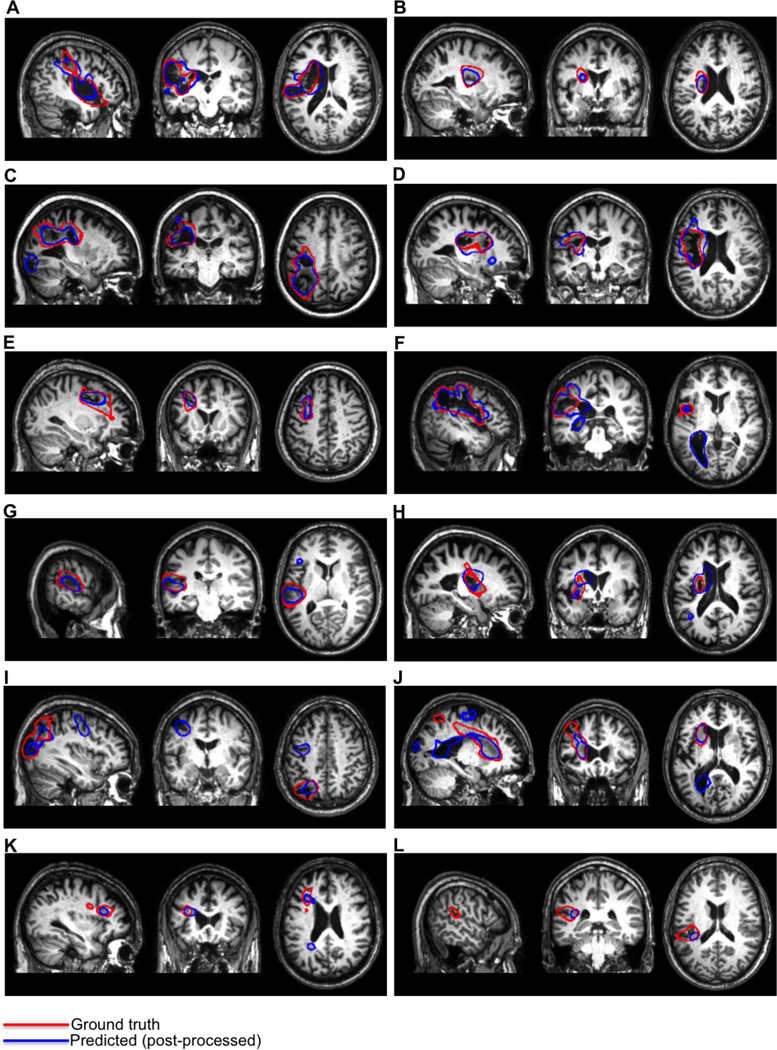

We also assessed differences between the groups in PVD. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to test whether median PVDs differed between the groups. This revealed that the median PVDs significantly differed between the groups (p < 0.001). Descriptive statistics for each group are shown in Table 5. Examples of post-processed predicted lesion delineations for cases with large lesions are shown in Fig. 6. Examples of post-processed predicted lesion delineations for cases with small lesions are shown in Fig. 7.

Table 5.

PVDs for large and small predicted lesion delineations (post-processed)

| Group | Mean | SD | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | 13.11 | 10.61 | 12.96 | 0.26–38.03 |

| Small | 44.69 | 24.50 | 43.93 | 1.08–91.38 |

Figure 6.

Outlines of post-processed predicted lesion delineations obtained from cross-validation (blue) and manual lesion delineations (red) are shown for 12 cases with large lesions.

Figure 7.

Outlines of post-processed predicted lesion delineations obtained from cross-validation (blue) and manual lesion delineations (red) are shown for 12 cases with small lesions.

4. Discussion

4.1 Advantages over other lesion delineation methods

While manual lesion delineation is currently considered the gold standard for identifying stroke lesions in MRI scans, it is both very time consuming (Wilke et al. 2011) and introduces the potential for biases that are inherent to subjective measurements (Fiez et al. 2000; Ashton et al. 2003). In this report, we presented a novel method for automatically delineating chronic stroke lesions from single-patient T1w MRI scans using GNB classification with strategically defined feature maps. We validated this method by comparing out-of-sample lesion predictions for 30 T1w scans obtained using leave-one-case-out cross-validation to the ground truth of manual lesion delineation by an expert. Our automated method was found to perform well for patients with lesions of varying sizes, shapes, and in various locations, and successfully detected the lesion location in 30/30 cases. The addition of simple post-processing steps (8mm FWHM smoothing + removal of clusters < 100 voxels) was found to improve performance.

Supervised learning methods are increasingly applied to classification problems in MRI research (Pereira et al. 2009; Wang and Summers 2012). Recently, ensemble classification methods based on extensions of decision tree algorithms have been applied in the context of chronic (Mitra et al., 2014) and sub-acute (Maier et al., 2014) stroke lesion classification with considerable success. However, the applicability of these methods to lesion delineation in the context of neuroimaging research is limited due to their dependence on T2-FLAIR MRI scans in addition to scans from other MRI modalities to achieve best performance, since these may not be acquired in the research setting. For example, the method proposed by Mitra and colleagues (2014) requires T1w, T2w, FLAIR, and DWI MRI scans to delineate chronic stroke lesions. In contrast, our method requires only the T1w MRI scans that are commonly collected in neuroimaging studies. This is advantageous because it allows the application of our method in functional neuroimaging research scenarios where only a single anatomical MRI scan, typically using T1w imaging, is acquired. Our method may be a more attractive option compared to existing automated (Seghier et al., 2008) and semi-automated (Wilke et al., 2011) fuzzy clustering methods for T1w lesion delineation, as it does not need scans from healthy controls, does not require substantial user interaction to achieve good results, and does not require ad-hoc statistical thresholding. Because it only requires a single T1w scan, our method also has applications in clinical scenarios for lesion volume estimation.

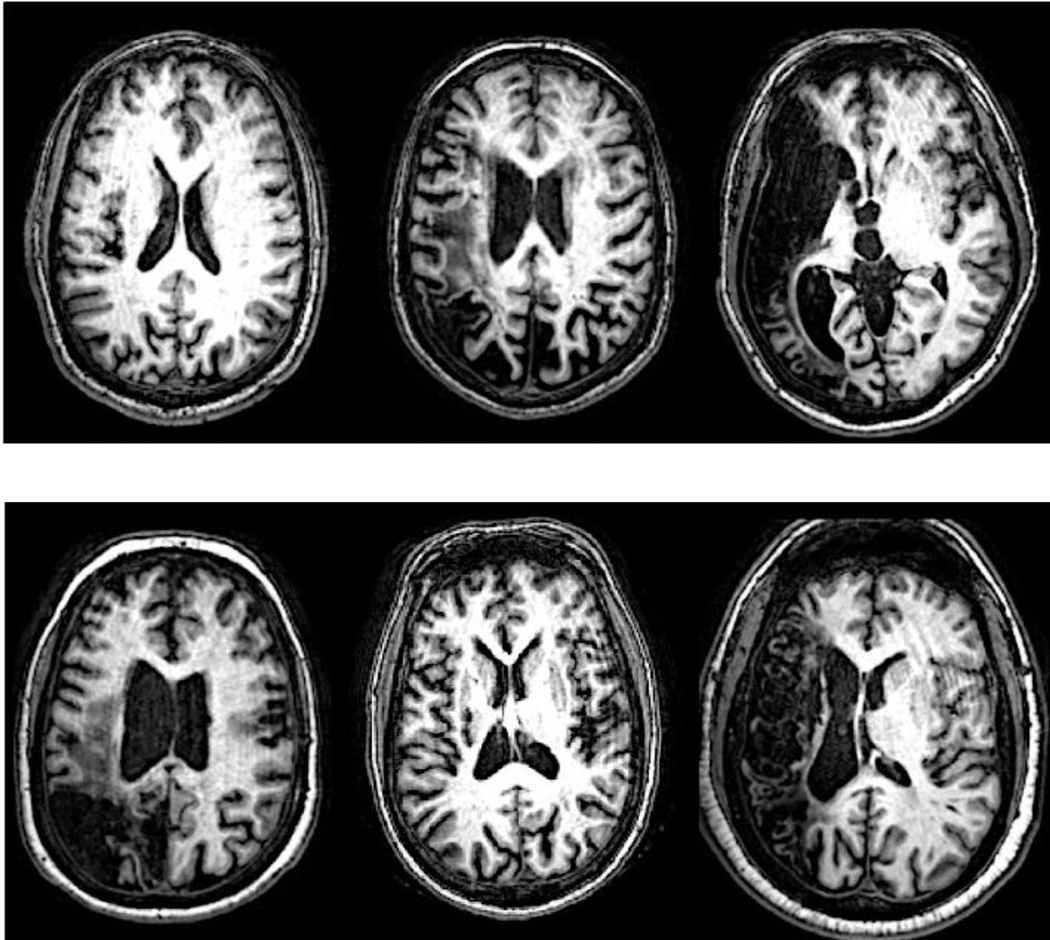

A potentially less obvious advantage of our method is that it requires only the default SPM12 segmentation and normalization procedures be performed before inputting TPMs into the feature extraction algorithm and applying the fully trained GNB classifier to predict lesion delineations for new cases. This makes our method straightforward and fast to apply to new cases, even for individuals with little experience using the SPM segmentation and normalization routines. The validation results also suggest that our method is at worst minimally affected by the presence of minor MRI image artifacts such as Gibbs artifacts (Fig. 8). This makes it potentially more robust than semi-automated approaches that use prior-less tissue segmentation (Wilke et al. 2011), especially in situations where scans are acquired with lower resolution or are contaminated by minor image artifacts.

Figure 8.

Native-space T1w scans from 6 cases with Gibbs artifacts are shown. Lesions were correctly identified for all cases.

Finally, unlike the other methods described here, our method attempts to explicitly provide separate features that aim to facilitate discrimination of both the lesion core that consists primarily of missing tissue and abnormal tissue that includes the penumbra and other remaining tissues affected by pathologies such as gliosis and demyelination. Indeed, supplementary analyses comparing performance between GNB classifiers that were trained on the same ground truth class labels using either the 2 feature maps as predictors (as described in this report) or the smoothed TPMs/PPMs (a total of 9 single-hemisphere volumes reoriented to “affected” hemisphere space) as predictors found that the use of the 2 feature maps as predictors yielded much better results than the TPMs alone (Supplementary S1). This appeared to be driven largely because the GNB classifier that used the 2 feature maps as predictors was much more sensitive to abnormal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 1).

4.2 Performance relative to other methods

Considering our validation results within the context of those reported by other, similar studies indicates that our method compares favorably to other methods for T1w lesion delineation, and performs comparably to methods that utilize multi-modal MRI data. Indeed, DSCs obtained using our method (median DSC = 0.73 for all 30 patients using post-processing) compared favorably to the performance of the ALI method (median DSC = 0.49 for 11 patients) and the semi-automated method (median DSC = 0.60 for 11 patients) as reported by Wilke and colleagues in their comparison of the two methods (2011)

Notably, DSCs obtained using our method also compared favorably to other supervised learning methods that utilize multi-modal MRI data. For example, Mitra and colleagues (2014) reported a median DSC of 0.60 for 37 patients using a random-forest procedure that requires T1w, T2w, FLAIR, and DWI scans for chronic stroke lesion delineation. Similarly, Maier and colleagues (2014) reported a median DSC of 0.68 for 35 cases using an extra-tree forest procedure after exempting 2 failed cases from their results, although their method is focused on sub-acute lesion delineation.

Results from our volumetric analyses indicate that PVDs for lesion delineations obtained using our method (median PVD = 0.23 for 30 cases) compare favorably to those reported by Mitra and colleagues (2014) for their random forest method (median PVD = 0.34 for 36 cases). A previous study investigating inter- and intra-rater reliability between two raters for manual lesion delineation reported median intra-rater PVDs of 12.5% and 9%, and a median inter-rater PVD of 14.5% for 10 cases (Fiez et al. 2000). The other references cited above did not use PVD as an evaluation metric, but PVDs for lesion delineations predicted by our method appear to be between those reported by other methods and what would be expected based on inter-rater variability. In addition, the strong linear correlation between volume estimates obtained using our method (r = 0.97) compares favorably to that reported by Mitra (2014) and colleagues (r = 0.76). This indicates that lesion volumes obtained using our method are a nearly perfect linear transformation of lesion volumes obtained from manual delineation, and this is important for applications where correlations between lesion volumes and other measures might be investigated or where lesion volumes might be used as a covariate to control for the effects of lesion size on another variable of interest.

The detailed comparisons between the validation results obtained using our method and those reported by other methods is intended to provide context for interpreting our quantitative validation results. It is important to note, however, that because our method was not explicitly compared to any of the referenced methods, the comparisons of quantitative results are not intended to provide a basis for strong conclusions about the relative performance of these methods. Strong inferences about the superiority of a given method should only be made by direct comparisons on the same dataset. Currently, none of the referenced methods are publicly available, and this complicates direct comparisons. However, we expect that by making our fully trained classifier and feature extraction algorithm publicly available, our method can be compared to other existing methods and potentially improved/expanded in the future.

For example, it would be highly informative to directly compare our method against other current methods for T1w lesion delineation. In particular, it would be interesting to see whether our method can achieve superior lesion delineation compared to the ALI tool (Seghier et al., 2008) or the semi-automated method proposed by Wilke and colleagues (2011) on this sample or on a similarly sized sample in order to determine if a particular method is optimal for T1w lesion delineation. Thus, future extensions of the current study include detailed comparisons with other methods for T1w lesion delineation once they are made publicly available. It would also be interesting to compare our method and the above methods to other approaches that utilize T2-FLAIR MRI scans to achieve lesion delineation, such as the methods proposed by Mitra and colleagues (2014) and Maier and colleagues (2014). Indeed, white matter lesion effects such as gliosis and demyelination are readily apparent in FLAIR scans given their hyper-intense appearance (Adams and Meihem 1999). It might be expected that our use of feature maps that specifically aim to enhance discrimination of abnormal tissue might give our method an advantage over other T1w lesion delineation techniques when compared to techniques that utilize FLAIR scans in addition to T1w scans. It is also important to note that, given the sensitivity of FLAIR scans to subtle WM lesion effects that may not be as apparent in T1w scans, methods that incorporate FLAIR information may provide better performance for cases with more subtle WM lesions.

4.3. Detection of challenging and indirect lesion effects

Our method detected lesion effects that are difficult to detect via visual examination of native-space T1w MRI scans. These include “indirect” lesion effects, such as ventricular abnormalities (Fig. 6G,I–K; Fig. 7. F,J) (Wilke et al. 2011), and damage/atrophy to medial sub-cortical structures (Fig. 6C,F,H–I; Fig. 7. A,B,D,E,H,J,K). Because these effects are often difficult to distinguish by eye in native-space MRI scans, automated or semi-automated methods for lesion delineation that use template-normalized MRI scans are ideal for detecting these effects (Wilke et al., 2011). Indeed, the majority of these “indirect” effects were not included in the ground-truth manual lesion delineations, and the sensitivity of our method to these effects actually led to lower DSCs and higher PVDs for several predicted lesion delineations that otherwise had high agreement with the manual delineations (Fig. 6; Fig. 7E). The ability to detect indirect lesion effects suggests that our method may be useful for investigations of structural reorganization in the chronic post-stroke recovery phase (Wilke et al., 2011), and may be more suited for such investigations than semi-automated approaches since there is less opportunity to introduce subjective biases.

In addition, our method detected direct lesion effects that were missed during manual delineation, resulting in lower DSCs and higher PVDs for several cases that had otherwise good agreement with the manual delineations. For example, our method detected additional tissue loss in the occipital cortex of the case shown in Fig. 7C, and tissue loss near the central sulcus of the case shown in Fig. 7E. The fact that these direct lesion effects were missed during manual delineation highlights the potential for even expert raters to make errors, and reinforces the point made by Wilke and colleagues (2011) that exact agreement with manual delineation is not expected or even necessarily optimal. While some false positives were also detected by our method (e.g. Fig.7I–K), in nearly every case they could be removed by the use of a somewhat larger cluster threshold while retaining the “true” lesion. As such, we recommend that predicted lesion delineations obtained using our method be visually inspected to ensure accuracy.

It is also worth discussing that our method showed good performance for cases with lesion effects that can pose challenges to automated lesion delineation (Seghier et al., 2008). Such effects include lesions that encompass midline cortical and sub-cortical structures, tissue loss near the ventricles, and widespread tissue loss, and multi-focal lesion effects. Our method was able to successfully delineate lesions in cases that presented with each of these effects. For example, the cases shown in Fig. 6F,I had extensive tissue loss with damage/atrophy in the head of the caudate, the case shown in Fig. 6H had extensive tissue loss with midline damage affecting the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex/pre-supplementary motor area, and many cases had damage adjacent to the ventricles (e.g. Fig. 6I–J,L; Fig. 7 A–B,D,F,H). Multi-focal lesion effects were also detected for the cases shown in Figs. 5E/7B,E. Notably, while our method showed sensitivity to ventricular enlargements and sub-cortical damage, it did not seem prone to misclassifying ventricular CSF or edge-of-brain voxels as lesion. This may be another advantage of our method over other methods for T1w lesion delineation, as they may be prone to this type of error (e.g. Fig. 6 in Wilke et al., 2011).

4.3 Potential limitations

While our method was found to perform well overall, it did miss a large portion of the lesion extent in the case shown in Fig. 7L, although it identified the portion adjacent to the WM. The poorer performance of our method on this case is likely due to its location combined with its small size. Indeed, inspection of Fig. 7L shows that it is almost entirely confined to the posterior portion of the superior temporal sulcus. Our method was much more successful on a case with a very similar lesion location (Fig. 7G), although the cortical extent of this case was somewhat larger, possibly facilitating detection. While it might be expected that smoothing the input TPMs with a smaller smoothing kernel might provide better delineation for these effects, additional analyses investigating the effects of smoothing kernel on classification performance did not provide evidence to support this expectation (Supplementary S2).

Our method is not intended for detecting very subtle WM lesions with very small extents, such as those that occur in multiple sclerosis (MS) or Alzheimer’s disease. Nonetheless, it successfully identified the lesion for the case with the lowest lesion volume (Fig. 7K; lesion volume = 1485 voxels) that consisted of a relatively subtle hypo-intense band of WM. As discussed in Section 4.1, methods for automated lesion delineation that utilize T2-FLAIR scans might provide better delineation for such subtle lesions such as these.

Another potential limitation of our method comes from the fact that it assumes that for each case, there exists an “affected” and “un-affected” hemisphere. Thus, similar to the semi-automated fuzzy clustering method proposed by Wilke and colleagues (2011), our method uses information about laterality in predicting whether voxels belong to the lesion class. It might be expected that the violation of this assumption, particularly by the presence of lesions that occupy homologous portions of the “un-affected” hemisphere, might confound feature map creation and result in poor lesion delineation. Contralateral lesions were observed in 4 cases included in the present sample, and 2 of these were in near-homologous regions. Interestingly, the results from the 2 cases where this assumption was violated suggest that this assumption may be violated without much impact on the quality of the predicted lesion delineation (Fig. 6A; Fig. 7C). Indeed, the highest DSC across all 30 cases was achieved for a case with extensive lesioning in similar portions of the “un-affected” hemisphere (Fig. 6A), and a “good” DSC of 0.63 was obtained for the other patient as well (Fig. 7C). The results from these cases suggest that the violation of this assumption is most likely to be problematic when the extent of the lesion in the “un-affected” hemisphere completely encompasses the lesion in the “affected hemisphere”. In such a case, feature maps could be created using only the “affected” hemisphere and smoothed PPMs. Indeed, results from additional analyses suggest that the exclusion of the unaffected hemisphere from the creation of feature maps only slightly reduces the quality of the predicted lesion delineations, although this did cause it to fail on the case shown in Fig. 7L (Supplementary S4). Another alternative would be to use a scan from a control subject or the unaffected hemisphere taken from a different patient’s scan to overcome this limitation, although we have not investigated the efficacy of these alternatives.

5. Conclusions

In this report, we presented a novel algorithm for automatically creating lesion masks using single-patient T1w MRI scans. We validated our method by comparing it to manual lesion delineation by an expert neuroanatomist. The results of our validation indicate that our method is able to generate high-quality lesion masks for patients with a diverse range of lesion sizes, shapes, and locations. Our method was sensitive to indirect lesion effects that can be difficult to detect via visual inspection of native-space T1w scans, and even identified direct lesion effects that were missed during manual delineation. Notably, performed well even for patients with damage in both hemispheres as well as for MRI scans containing minor image artifacts. Our method, therefore, has potential applications in both research and clinical settings. While visual inspection of the lesion masks is still necessary to ensure quality, our method substantially reduces the amount of time and effort dedicated to delineating lesions for use in lesion-behavior mapping studies, and may also provide a straightforward, consistent and reliable means for estimating lesion volumes and extents in a clinical setting. The MATLAB code used for pre-processing and feature-map creation, as well as the fully trained (on all 30 cases) GNB classifier will be made publicly available upon publication.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

We present a novel method for lesion delineation in individual T1 MRI scans.

-

-

We compared our method with manual delineation for a large group of stroke patients.

-

-

Our method reliably predicted lesion extents and volumes.

-

-

Our method identified lesion effects that pose challenges for manual delineation.

-

-

Our method can be used for lesion-symptom mapping and clinical volume estimation.

ETHICAL STANDARDS.

The authors declare that all experiments on human subjects were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki http://www.wma.net and that all procedures were carried out with the adequate understanding and written consent of the subjects.

The authors also certify that formal approval to conduct the experiments described has been obtained from the human subjects review board of their institution and could be provided upon request.

If the studies deal with animal experiments, the authors certify that they were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80–23) revised 1996 or the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and associated guidelines, or the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC).

The authors also certify that formal approval to conduct the experiments described has been obtained from the animal subjects review board of their institution and could be provided upon request.

The authors further attest that all efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

If the ethical standard governing the reported research is different from those guidelines indicated above, the authors must provide information in the submission cover letter about which guidelines and oversight procedures were followed.

The Editors reserve the right to return manuscripts in which there is any question as to the appropriate and ethical use of human or animal subjects.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by R01 NS048281 and in part by R01 HD068488.

The authors thank Wesley Burge, Rodolphe Nenert, Kristina Visscher, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This study was presented in part at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping.

References

- Adams JG, Meihem ER. Clinical Usefulness of T2-Weighted Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery MR Imaging of the CNS. Am J Radiol. 1999 Feb;172 doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton Ea, Takahashi C, Berg MJ, Goodman A, Totterman S, Ekholm S. Accuracy and reproducibility of manual and semiautomated quantification of MS lesions by MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(3):300–308. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian HC. On Different Kinds of Aphasia, with Special Reference to Their Classification and Ultimate Pathology. Br Med J. 1887;2:985–990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.1401.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Wilson SM, Saygin AP, Dick F, Sereno MI, Knight RT, et al. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(5):448–450. doi: 10.1038/nn1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berker Ea, Berker a H, Smith a. Translation of Broca’s 1865 report. Localization of speech in the third left frontal convolution. Arch. Neurol. 1986:1065–1072. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520100069017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha L, Rorden C, Fridriksson J. Assessing the clinical effect of residual cortical disconnection after ischemic strokes. Stroke. 2014;45(4):988–993. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Herskovits EH. Voxel-based Bayesian lesion-symptom mapping. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2010;49(1):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Ramsey L, Callejas A, Baldassarre A, Hacker CD, Siegel JS, et al. Common Behavioral Clusters and Subcortical Anatomy in Stroke. Neuron. Elsevier Inc. 2015;85(5):927–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crinion J, Ashburner J, Leff A, Brett M, Price C, Friston K. Spatial normalization of lesioned brains: Performance evaluation and impact on fMRI analyses. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2007;37(3):866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crinion J, Holland AL, Copland Da, Thompson CK, Hillis AE. Neuroimaging in aphasia treatment research: quantifying brain lesions after stroke. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2013 Jun;73:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dice LR. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species. Ecology. 1945;26(3):297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Domingos P, Pazzani M. On the optimality of the simple Bayesian classifier under zero-one loss. Mach Learn. 1997;29:103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers NF, Plaisant O, Iba-Zizen MT, Cabanis Ea. Paul Broca’s historic cases: High resolution MR imaging of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong. Brain. 2007;130(5):1432–1441. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiez Ja, Damasio H, Grabowski TJ. Lesion segmentation and manual warping to a reference brain: Intra- and interobserver reliability. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9(4):192–211. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200004)9:4<192::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridriksson J, Fillmore P, Guo D, Rorden C. Chronic Broca’s Aphasia Is Caused by Damage to Broca's and Wernicke's Areas. Cereb Cortex. 2014 Jul;11:1–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva S, Baron J-C, Jones PS, Price CJ, Warburton Ea. A comparison of VLSM and VBM in a cohort of patients with post-stroke aphasia. NeuroImage Clin. The Authors. 2012 Jan;1(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitelman DR, Ashburner J, Friston KJ, Tyler LK, Price CJ. Voxel-based morphometry of herpes simplex encephalitis. Neuroimage. 2001;13(4):623–631. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O, Wilms M, von der Gablentz J, Krämer UM, Münte TF, Handels H. Extra Tree forests for sub-acute ischemic stroke lesion segmentation in MR sequences. J Neurosci Methods. Elsevier B.V. 2014;240C:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Grabowski TJ, Trivedi Y, Damasio H. Evaluation of voxel-based morphometry for focal lesion detection in individuals. Neuroimage. 2003;20(3):1438–1454. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra J, Bourgeat P, Fripp J, Ghose S, Rose S, Salvado O, et al. Lesion segmentation from multimodal MRI using random forest following ischemic stroke. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2014;98:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F, Mitchell T, Botvinick M. Machine learning classi!ers and fMRI: A tutorial overview. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S199–S209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada RDS, Lee YS. Smoothness without Smoothing: Why Gaussian Naive Bayes Is Not Naive for Multi-Subject Searchlight Studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripollés P, Marco-Pallarés J, de Diego-Balaguer R, Miró J, Falip M, Juncadella M, et al. Analysis of automated methods for spatial normalization of lesioned brains. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2012 Apr 2;60(2):1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rish I, Hellerstein J, Jayram T. An analysis of data characteristics that affect naive Bayes performance. Tec Rep RC21993, IBM Watson. 2001 Jan [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Fridriksson J, Karnath HO. An evaluation of traditional and novel tools for lesion behavior mapping. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2009;44(4):1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Karnath H-O, Bonilha L. Improving lesion-symptom mapping. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:1081–1088. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.7.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML, Ramlackhansingh A, Crinion J, Leff AP, Price CJ. Lesion identification using unified segmentation-normalisation models and fuzzy clustering. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2008;41(4):1253–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turken AU, Dronkers NF. The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011 Jan;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001. February. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Summers RM. Machine learning and radiology. Med Image Anal. Elsevier B.V. 2012;16(5):933–951. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, de Haan B, Juenger H, Karnath H-O. Manual, semi-automated, and automated delineation of chronic brain lesions: a comparison of methods. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2011 Jun 15;56(4):2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Staudt M, Juenger H, Grodd W, Braun C, Krägeloh-Mann I. Somatosensory system in two types of motor reorganization in congenital hemiparesis: Topography and function. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(3):776–788. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. The Optimality of Naive Bayes. Proc Seventeenth Int Florida Artif Intell Res Soc Conf FLAIRS 2004. 2004;(2):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Exploring Conditions for the Optimality of Naïve Bayes. Int J Pattern Recognit Artif Intell. 2005;19(02):183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zou KH, Warfield SK, Bharatha A, Tempany CMC, Kaus MR, Haker SJ, et al. Statistical validation of image segmentation quality based on a spatial overlap index1. Acad Radiol. 2004;11(2):178–189. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)00671-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.