Abstract

Objective

The development of operative skill during general surgery residency depends largely on the resident surgeons’ ability to accurately self-assess and identify areas for improvement. We compared evaluations of laparoscopic skill and comfort level of resident surgeons from both the resident surgeon’s and attending surgeon’s perspectives.

Design

We prospectively observed 111 elective cholecystectomies at the University of Michigan as part of a larger quality improvement initiative. Immediately after the operation, both resident and attending surgeons completed a survey in which they rated the resident’s operative proficiency, comfort level, and the difficulty of the case using a previously validated instrument. Resident’s and attending’s evaluations of resident performance were compared using two-sided t-tests.

Setting

The University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, MI. Large academic, tertiary care institution.

Participants

All general surgery residents and faculty at the University of Michigan performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy between June 1st and August 31st 2013. Data was collected for 28 of the institution’s 54 trainees.

Results

Attendings rated residents higher than residents rated themselves on a five-point Likerttype scale with regards to depth perception (3.86 vs. 3.38, p<0.005), bimanual dexterity (3.75 vs. 3.36, p=0.005), efficiency (3.58 vs. 3.18, p<0.005), tissue handling (3.69 vs. 3.23, p<0.005), and comfort performing case (3.86 vs. 3.38, p<0.005). Attendings and residents were in agreement on the level of autonomy displayed by the resident during the case (3.31 vs. 3.34, p=0.85), the level of difficulty of the case (2.98 vs. 2.85, p=0.443), and the degree of teaching done by the attending surgeon during the case (3.61 vs. 3.54, p=0.701).

Conclusions

A gap exists between resident and attending surgeons’ perception of residents’ laparoscopic skills and comfort level in performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. These findings call for improved communication between residents and attendings in order to ensure that graduates are adequately prepared to operate independently. In the context of changing methods of resident evaluations that call for explicitly defined competencies in surgery, it is essential that residents are able to accurately self-assess, and be in general agreement with attending surgeons on their level of laparoscopic skill and comfort level performing a case.

Introduction

The development of operative skills throughout general surgery training depends on the resident surgeon’s (resident’s) ability to self-assess strengths and weaknesses.1–4 Accurate identification of technical strengths and deficiencies allows the surgeon to actively work toward improvement and track their progression. To facilitate this improvement, it is important that attending surgeons (attendings) and residents are in agreement regarding resident surgical skills and comfort level.5 With the introduction of the ACGME Milestones, it is becoming even more crucial that residents not only gain adequate experience but also make a conscious, self-directed effort to learn and improve in the process. Furthermore, it is important that attendings understand how to accurately evaluate resident competency as the Milestones continue move us toward more competence-based assessment. With growing responsibilities and limited time, residents face increasing, and at times conflicting, pressure to learn both thoroughly and rapidly in order to become competent surgeons upon completion of their training.6

Previous studies suggest attendings are less critical of resident’s technical skills than residents are of themselves.7,8 This disparity in the perception of technical skills may be detrimental to the learning environment.7 A resident who is more critical and less comfortable with his/her skills may expect more teaching from the attending than the attending realizes. However, some residents fear that actively seeking assistance will be perceived as a sign of weakness.9 Better teaching can be facilitated by improved communication between residents and attendings in the operating room regarding technical skill and comfort level.8,10 Residents rank an attending’s willingness to teach as the most important factor driving learning in the operating room.11 This is especially important because previous research shows that, compared to attendings’ perception of feedback provided, residents are less satisfied with the intraoperative feedback they receive.12 Better communication may contribute to the resident’s ability to accurately self-assess technical skills, promoting improved autonomy and clear progression throughout the surgeon’s career.5,7,12–14

The purpose of this study is to examine and compare attending and residents’ perceptions of laparoscopic skills, comfort level, and degree of operative teaching. We hypothesize that residents’ self-evaluations will be lower than that of their attending counterparts, reflecting a perception gap. To test this, we directly observed a series of laparoscopic cholecystectomies and asked attendings and residents to complete a survey immediately postoperatively to rate the resident’s laparoscopic skills, comfort level, and the degree of operative teaching during the case.

Material and Methods

Data Collection Instrument

Over a three-month period between June and August 2013, 111 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were prospectively observed at the University of Michigan Health System as part of a larger quality improvement initiative.15 Within this initiative, we sought to examine operative teaching and the discrepancy between resident and attending perceptions. At the conclusion of each case, the resident and attending were independently provided with a survey (Appendix 1) in which they rated the resident’s operative proficiency, comfort level, and the difficulty of the case. The survey used an externally validated measure of laparoscopic skill: the Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills (GOALS).16 The GOALS measure is a five-point Likert-type scale assessing residents’ performance in five domains (depth perception, bimanual dexterity, efficiency, tissue handling, and autonomy), and has been shown to have high inter-rater reliability for assessment of laparoscopic skill.16

In addition to the GOALS ratings, residents and attendings were surveyed on their comfort level performing the operation, the amount of intraoperative teaching that they perceived took place during the case, and the residents’ level of involvement at each critical step of the operation. Residents were also asked about their prior level of experience performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Statistical Analysis

Resident and attending survey responses were compared using two-sided t-tests for each aspect of the GOALS scale. Resident and attending assessments of the case’s difficulty and the level of the resident’s involvement performing the operation were also compared.

This project was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. All analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Residents who performed laparoscopic cholecystectomy during our study ranged from PGY1 to PGY5. Of the 111 laparoscopic cholecystectomies observed, residents in their third post-graduate year (PGY3) performed the highest number of cases (54 cases, 48.6% of total cases), followed by PGY 4, PGY 5, PGY 2 and PGY 1 residents. Fellows performed 2 of the 111 cases (1.8%). In addition to a having a range of PGY levels, residents had a broad range of previous experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Only three cases were performed by a resident who had never before performed more than 50% of the operation as the primary surgeon. The highest percentage of cases was performed by residents who had performed 11–20 laparoscopic cholecystectomies (36.8%), followed by residents who had performed greater than 20 cases (34.2%), residents who had performed 4–10 cases (12%), and residents who had performed 1–3 cases (9.4%) The complete distribution of cases by resident experience and post-graduate year is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of cases by resident post-graduate year and experience.

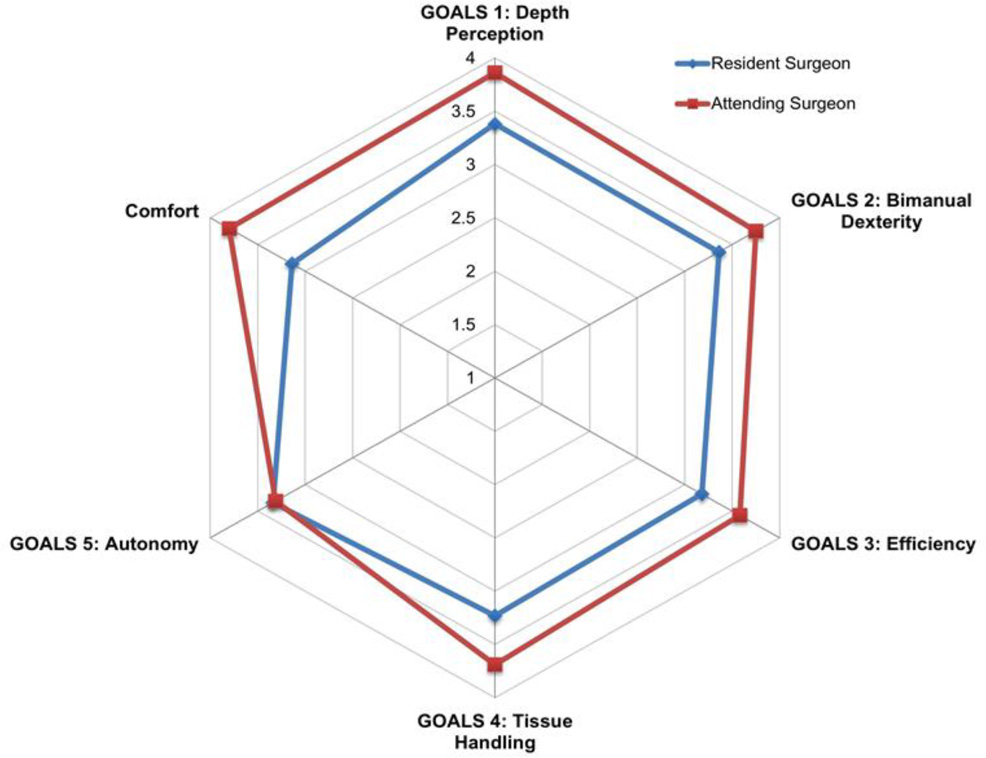

Our primary finding was that the attending surgeons consistently rated residents’ laparoscopic skills significantly higher than residents rated themselves. On average, attending surgeons ranked residents’ laparoscopic skills 0.35 points higher on the 5-point GOALS scale (p <.005). Attendings rated residents significantly higher than residents rated themselves in each of the following laparoscopic skills: depth perception (3.86 vs. 3.38, p<0.005), bimanual dexterity (3.75 vs. 3.36, p=0.005), efficiency (3.58 vs. 3.18, p<0.005), tissue handling (3.69 vs. 3.23, p<0.005), comfort performing case (3.86 vs. 3.38, p<0.005). Figure 2 graphically displays the consistent gap between resident and attending perceptions across the GOALS domains, with the exception of autonomy on which there was strong agreement. Table 1 summarizes the attending and resident evaluations of resident laparoscopic skills in each domain.

Figure 2.

Resident vs attending surgeon perception on Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills (GOALS) domains.

Table 1.

Attending and Resident Evaluation of Resident Laparoscopic Skill

| Laparoscopic Skill | Attending Assessment | Resident Assessment | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOALS 1: Depth Perception* | 3.86 ± .966 | 3.38 ± .817 | < 0.005 |

| GOALS 2: Bimanual Dexterity** | 3.75 ± 1.00 | 3.36 ± .998 | 0.005 |

| GOALS 3: Efficiency | 3.58 ± 1.04 | 3.18 ± .882 | < 0.005 |

| GOALS 4: Tissue Handling | 3.69 ± .914 | 3.23 ± .842 | < 0.005 |

| Comfort Performing Case | 3.80 ± 1.34 | 3.14 ± 1.76 | < 0.005 |

Depth perception: Accurately directing instruments in correct plane to target; without overshooting or missing plane

Bimanual Dexterity: The coordinated use of both hands in a complementary manner to provide optimal working exposure

Attendings and residents agreed on the level of autonomy displayed by the resident during the case (3.31 vs. 3.34, p=0.85), the level of difficulty of the case (2.98 vs. 2.85, p=0.443), and the degree of teaching done by the attending surgeon during the case (3.61 vs. 3.54, p=0.701) (Table 2). As a sensitivity analysis, we subdivided cases by the level of teaching (“high” teaching >3; “low” teaching ≤3), we saw that this gap persisted. We also subdivided cases by difficulty (difficult case being defined as rating of >3 by the attending or resident) and found that the gap in perception persisted across case difficulty. Table 3 shows the skill ratings by residents and attendings, subdivided by case difficulty and amount of teaching. A statistically significant gap persisted in difficult cases; in less difficult cases there was still a small gap, however due to loss of power in this smaller sample size this did not achieve statistical significance.

Table 2.

Attending and Resident Assessment of Case Difficulty and Attending Involvement

| Case Characteristics | Attending Assessment | Resident Assessment | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOALS 5: Autonomy | 3.31 ± 1.01 | 3.34 ± .999 | 0.854 |

| GOALS 6: Level of Difficulty | 2.98 ± 1.27 | 2.85 ± 1.08 | 0.443 |

| Assessment of Teaching during Case | 3.61 ± 1.23 | 3.54 ± 1.18 | 0.701 |

Table 3.

Attending and Resident Evaluations of Resident Laparoscopic Skill, Stratified by Case Difficulty as well as by Amount of Intraoperative Teaching

| Case Difficulty >3 | Case Difficulty | |||||

| Laparoscopic Skill |

Attending Assessment |

Resident Assessment |

Attending Assessment |

Resident Assessment |

||

| GOALS 1: Depth Perception* | 3.75 ± .994 | 3.18 ± .736 | <.001 | 4.02 ± .913 | 3.68 ± .850 | 0.08 |

| GOALS 2: Bimanual Dexterity** | 3.66 ± 1.06 | 3.26 ± .991 | 0.033 | 3.88 ± .905 | 3.51 ± 1.00 | 0.08 |

| GOALS 3: Efficiency | 3.52 ± 1.04 | 2.98 ± .799 | 0.002 | 3.67 ± 1.04 | 3.48 ± .926 | 0.38 |

| GOALS 4: Tissue Handling | 3.62 ± .986 | 3.08 ± .816 | 0.001 | 3.79 ± .804 | 3.46 ± .839 | 0.07 |

| Comfort Performing Case | 3.69 ± 1.41 | 2.81 ± 1.64 | 0.001 | 3.97 ± 1.24 | 3.71 ± 1.84 | 0.43 |

| High Teaching (>3) | Low Teaching | |||||

| Laparoscopic Skill |

Attending Assessment |

Resident Assessment |

Attending Assessment |

Resident Assessment |

||

| GOALS 1: Depth Perception* | 3.52 ± .891 | 3.02 ± .700 | 0.001 | 4.43 ± .813 | 3.75 ± .771 | <.001 |

| GOALS 2: Bimanual Dexterity** | 3.41 ± .955 | 2.96 ± .885 | 0.011 | 4.3 ± .823 | 3.76 ± .951 | 0.006 |

| GOALS 3: Efficiency | 3.02 ± .929 | 2.73 ± .660 | 0.003 | 4.2 ± .912 | 3.65 ± .844 | 0.004 |

| GOALS 4: Tissue Handling | 3.33 ± .818 | 2.90 ± .774 | 0.005 | 4.28 ± .751 | 3.57 ± .781 | <.001 |

| Comfort Performing Case | 3.33 ± 1.11 | 2.11 ± 1.14 | <.001 | 4.57 ± 1.36 | 4.2 ± 1.66 | 0.242 |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a gap exists between resident and attending surgeons’ perception of laparoscopic skills and comfort level in performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Attending surgeons consistently rated the resident’s laparoscopic skill level higher than the residents rated their own ability. In addition, attending surgeons rated their comfort with residents performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy higher than residents rated their own comfort level. Although there was disagreement on laparoscopic skill and comfort level, resident and attending surgeons did agree on the amount of operative teaching that occurred during the case. Across cases with both high and low levels of operative teaching, as well as across case difficulties, the gap in perception of skills and comfort level persists.

The notion of a perception gap has been documented in a number of previous studies. Our study combined direct observation of each individual operation and immediate postoperative assessment. This builds on the existing literature by capturing data on a case-by-case basis; our hope is that this approach allows for a more accurate accurate comparison of perceptions based on the case just performed, rather than a one-time survey that reflects attending and residents’ perception of the resident’s overall performance. The gap in perception of both laparoscopic skill and comfort level that exists between resident and attending surgeons poses a potential problem in the education and growth of residents. A resident who is more critical and less comfortable with his/her skills may desire more instruction than he/she receives, which hinders learning. Further, residents may develop inaccurate self-perception that hinder their confidence and motivation for improvement.7

The identification of this gap calls for an improvement in communication and feedback between surgeons. Additionally, our finding that the gap in perception of skills and comfort persists in cases with both high and low levels of operative teaching suggests that attending surgeons are not appropriately tailoring their instruction to the needs and competency of the resident. Quality communication between resident and attending surgeons allows teachers to tailor their instruction for the resident’s own comfort and skill level.4 It has been shown that residents are less satisfied with the amount of feedback they receive than attending surgeons are with the amount of feedback they provide.12 Based on the subjective nature of our survey, we can only observe that discrepancies exist between residents and attendings, but there is no way to determine whose perception is truly accurate. The existence of a gap in perception is more important than determining whose perception is most correct, as designating either residents or attendings as the accurate perception of competency presents a problem. If attendings’ evaluations are used as the “gold standard”, our findings suggest that residents are not confident in their skills. Conversely, if it is residents who are accurately evaluating their skills, attendings are not accurately gauging competency. Regardless of whose evaluation is accurate, our findings suggest that programs may be graduating residents who are ill prepared for independent practice. Program directors and attending surgeons looking to improve the educational experience should consider these discrepancies when considering how feedback should be provided to residents intraoperatively.

Looking forward, these findings are important in the context of the implementation of the ACGME Milestones Project, which calls for resident evaluations to be based on explicitly defined competencies in surgery. In addition, entrustable professional activities (EPAs) help attending surgeons decide how much supervision is needed by a resident in a specific task based on their competency.17 The EPAs allow ACGME Milestones to be observed and evaluated in daily clinical practice. The discrepancy in perception of laparoscopic skills between resident and attending surgeons observed in our study highlight the importance of involving residents directly in their own evaluations. Without resident input, an attending surgeon could rate a resident as competent in a particular technical skill that the resident feels uncomfortable performing. While the Milestones attempt to address this problem, methods are needed to operationalize the proposed milestones for assessment in daily practice, and the implementation of entrustable professional activities for evaluation in surgery may provide a method of doing so. When designing EPAs, it is important that residency program directors consider the discrepancy in perception of skills between resident and attending surgeons. To minimize the effect of this discrepancy, EPAs should be as specific and objective as possible, giving residents and attendings a more accurate understanding of resident competency.

Failure to consider resident input may contribute to graduating a resident who does not perceive him or herself adequately prepared to practice autonomously. Additionally, since the implementation of work hour limitations, there is ongoing concern that graduating residents will not be ready to practice independtly upon graduation. According to a recent survey, surgical fellowship program directors feel that 30 percent of incoming fellows are unable to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy independently.18 Our findings suggest that this concern is also emanating from residents, who consistently rated their comfort level with performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy lower than attending surgeons rated their comfort level with residents performing the operation.

The results of this study are limited in that data was collected at a single institution, with surveys completed following a single procedure, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, over a three-month period. However, investigation of one type of operation allowed for consistency in evaluation of skill, comfort, and difficulty level, as the survey instrument was not influenced by varying operations with a broad range of complexity. In addition, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common procedure that general surgery residents perform. Furthermore, during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the attending and residents are on opposite sides of the patient, which leads to distinct roles of a primary and assisting surgeon during the procedure. These defined roles are more conducive to teaching and guidance rather than attending takeover, as the attending and residents must stop operating and walk to the other side of the patient to change roles. Because there is little ambiguity as to who the primary surgeon is during the case, our survey responses accurately portray the perceptions of the resident’s involvement, skill level, and comfort during the case. In an open abdominal procedure, attending surgeons may offer varying levels of assistance, causing the resident to have an inaccurate perception of his/her own skills and autonomy.

Our finding that resident and attending surgeons were in agreement on the level of autonomy exhibited by the resident during the operation shows that there was no ambiguity regarding the involvement of the resident. While our study was only conducted over a three-month period, this covers a quarter of the calendar year with a very common procedure, so the majority of the institution’s clinically active residents were included. Another potential limitation of this study is the manner in which the survey was administered. Immediately following an operation, both the attendings and residents have many responsibilities, such as writing the operative note and meeting with the patient’s family. However, the immediate administration of the survey after the conclusion of a case was intended to capture responses that more accurately reflect details of that specific case, rather than a general evaluation of the resident’s overall performance. Finally, due to the large number of different resident-attending combinations, there is not enough power to give insight into how these dyads may affect evaluation. Resident and attending surgeons may have pre-established relationships that affect the way the attending perceives the resident’s skill and comfort level. Future studies may be useful to determine the effect of the attending-resident dyad, as well as whether discrepancies between resident and attending surgeons’ perception of skill and comfort level persist across multiple institutions and for other procedures.

In summary, we found that residents underestimated their laparoscopic skills and comfort level in comparison to attending surgeons, but generally agreed on the difficulty of the operation and the degree of operative teaching that occurred during each case. These findings carry important implications for the future of resident education in the context of work hour limitations and evolving methods of evaluation. It is important for attending surgeons to understand a resident’s self-perception of his/her technical skills and comfort level so that attending surgeons can tailor their operative instruction appropriately. Additionally, lower ratings of skill and comfort by residents, compared to attending surgeons, may add to growing concerns regarding the graduation of residents that are not adequately prepared to practice independently. While residents may possess the technical skill needed for practice, if they lack confidence and awareness in these skills, this will hinder their readiness for independent practice as an attending. Further focus is needed on not simply developing residents’ technical skills, but developing their confidence in those skills as well. Two recent studies have assessed this issue of confidence as well. Friedell et al19 surveyed graduating residents and found that overall residents expressed confidence practicing independently and performing a broad range of general surgery procedures “comfortably”. However, this study did show a lack of comfort performing more complex and uncommon procedures such as hepatobiliary cases and advanced laparoscopy, echoing similar findings from Fonseca and colleagues.20 Our findings build upon these recent surveys by providing more granular detail – rather than simply surveying residents globally regarding confidence we obtained real-time discrete skill ratings. Our findings, namely the contrast between resident and attending perspective, reinforce that trainees appear to lack confidence in their operative skills. These gaps in perception of skill and comfort have the potential to lead to poor communication between resident and attending surgeons that may not adequately address the underlying impediment to resident’s education and growth.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

We prospectively observed 111 laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

-

-

We examined resident and attending perceptions of operative skill and comfort.

-

-

Residents underrated their skills and comfort level compared to attending surgeons.

-

-

Attendings and residents agreed on the difficulty of the case.

-

-

This perception gap calls for better attending-resident communication.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Scally is supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (5T32CA009672-23). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the federal government. This study was supported by the University of Michigan’s Transforming Learning for Third Century grant (TLTC).

Abbreviations

- GOALS

Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills

- PGY

Post-Graduate Year

- EPA

Entrustable Professional Activity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lipsett PA, Harris I, Downing S. Resident self-other assessor agreement: influence of assessor, competency, and performance level. Arch Surg. 2011;146:901–906. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey VA, Wolfe JH, Black SA, et al. Self-assessment of technical skill in surgery: the need for expert feedback. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:286–290. doi: 10.1308/003588408X286008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward M, MacRae H, Schlachta C, et al. Resident self-assessment of operative performance. Am J Surg. 2003;185:521–524. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer JA, Jordan RK. Learner centred approaches in medical education. BMJ. 1999;318:1280–1283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7193.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen XP, Williams RG, Smink DS. Do residents receive the same or guidance as surgeons report? Difference between residents' and surgeons' perceptions of or guidance. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:e79–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antiel RM, Thompson SM, Reed DA, et al. ACGME duty-hour recommendations - a national survey of residency program directors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyre SEMH, Al-Marayati L, Templeman C, Muderspach LI. Resident self-assessment versus faculty assessment of laparoscopic technical skills using a global rating scale. International Journal of Medical Education. 2010;1:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trajkovski T, Veillette C, Backstein D, Wadey VM, Kraemer B. Resident self-assessment of operative experience in primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty: Is it accurate? Can J Surg. 2012;55:S153–S157. doi: 10.1503/cjs.035510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo H, Viola K, Berg D, et al. Attitudes, training experiences, and professional expectations of US general surgery residents: a national survey. JAMA. 2009;302:1301–1308. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenton K. How to teach and evaluate learners in the operating room. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:325–332. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Hirose K, Lipsett PA. Duty hours and perceived competence in surgery: are interns ready? J Surg Res. 2014;190:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen AR, Wright AS, Kim S, Horvath KD, Calhoun KE. Educational feedback in the operating room: a gap between resident and faculty perceptions. Am J Surg. 2012;204:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyerson SL, Teitelbaum EN, George BC, Schuller MC, DaRosa DA, Fryer JP. Defining the autonomy gap: when expectations do not meet reality in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:e64–e72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paige JT, Aaron DL, Yang T, et al. Implementation of a preoperative briefing protocol improves accuracy of teamwork assessment in the operating room. Am Surg. 2008;74:817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waits SA, Reames BN, Krell RW, et al. Development of Team Action Projects in Surgery (TAPS): a multilevel team-based approach to teaching quality improvement. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vassiliou MC, Feldman LS, Andrew CG, et al. A global assessment tool for evaluation of intraoperative laparoscopic skills. Am J Surg. 2005;190:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:157–158. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258:440–449. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a191ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedell ML, VanderMeer TJ, Cheatham ML, et al. Perceptions of Graduating Surgery Chief Residents: Are they Confident in their Training? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonseca AL, Reddy V, Longo WE, et al. Operative Confidence of Graduating Surgery Residents: a Training Challenge in a Changing Environment. Am J Surg. 2014;207:797–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.