Abstract

Objective

To assess the cost-effectiveness of a pilot newborn screening (NBS) and treatment program for sickle cell anemia (SCA) in Luanda, Angola.

Study design

In July 2011, a pilot NBS and treatment program was implemented in Luanda, Angola. Infants identified with SCA were enrolled in a specialized SCA clinic in which they received preventive care and sickle cell education. In this analysis, the World Health Organization (WHO) and generalized cost-effectiveness analysis methods were used to estimate gross intervention costs of the NBS and treatment program. To determine healthy life-years (HLYs) gained by screening and treatment, we assumed NBS reduced mortality to that of the Angolan population during the first 5 years based upon WHO and Global Burden of Diseases Study 2010 estimates, but provided no significant survival benefit for children who survive through age 5 years. A secondary sensitivity analysis with more conservative estimates of mortality benefits also was performed. The costs of downstream medical costs, including acute care, were not included.

Results

Based upon the costs of screening 36 453 infants and treating the 236 infants with SCA followed after NBS in the pilot project, NBS and treatment program is projected to result in the gain of 452-1105 HLYs, depending upon the discounting rate and survival assumptions used. The corresponding estimated cost per HLY gained is $1380-$3565, less than the gross domestic product per capita in Angola.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate that NBS and treatment for SCA appear to be highly cost-effective across all scenarios for Angola by the WHO criteria.

Sickle cell disease is a significant global public health problem. In 2010, an estimated 312 000 infants throughout the world were born with homozygous sickle cell disease, a condition known as sickle cell anemia (SCA), the majority in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Mortality in SCA historically has been extremely high, with death often occurring before a diagnosis is made.2-4 In high-income countries, early diagnosis by newborn screening (NBS) and access to comprehensive care have resulted in survival to adulthood of over 95%.5,6 Implementation of NBS and early preventive care also has led to improved SCA survival in resource-limited settings, as demonstrated in Jamaica.7,8 In the US, universal NBS has been demonstrated to be cost-effective.9,10 A similar study in the United Kingdom was inconclusive, but universal screening was adopted nevertheless.10 Additional data regarding the cost-effectiveness of NBS, particularly in resource-limited settings, are limited. In contrast, routine NBS and access to treatment are not widely available in sub-Saharan Africa despite sporadic reports of pilot screening and treatment programs.11-16 The World Health Organization (WHO) has challenged African nations to address urgently the growing burden of SCA,17,18 but SCA remains a low priority compared with other health problems.19

Our study intended to demonstrate that NBS for SCA accompanied by preventive care can be cost-effective in a high prevalence, resource-constrained setting in sub-Saharan Africa. This study began as part of a 3-way collaboration among Chevron, Baylor College of Medicine, and the Ministry of Health in the Republic of Angola. The pilot NBS and treatment program, performed in Luanda, Angola, demonstrated a 1.5% prevalence of SCA in newborns.11 The pilot program demonstrated the feasibility of performing both NBS and early clinical care in this limited-resource setting. The current analysis builds upon the pilot study by analyzing costs and projected mortality and morbidity changes to address the question of NBS cost-effectiveness. In so doing, we hope to provide information on the potential costs and health impact of implementation of NBS for SCA in an African setting.

Methods

In this report, we use data from the pilot program to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of a realistic model for NBS and treatment in Angola.

We used the modified WHO-choosing Interventions that are cost-effective (CHOICE) and generalized CEA methods to estimate intervention costs in order to maximize generalizability.20 Intervention costs were calculated for 2 components: (1) the pilot NBS program; and (2) the provision of care through age 5 years to those enrolled for care during the 2-year pilot phase. Costs of tradeable goods were converted to international dollars (I$) using the market exchange rate and untradeable goods and services using the purchasing power parity exchange rate.21,22

Screening costs included supplies for sample collection, maternity nurse labor for specimen collection, transport of samples to the central laboratory, and laboratory costs to include personnel to perform isoelectric focusing on all samples. Care costs included personnel (doctors, nurses, and clinic coordinator) and treatments, as well as clinic overhead (physical space, telecommunications, and computer needs). Treatment costs were calculated as the expected costs of providing ongoing sickle cell education and routine clinical care, including measurement of hemoglobin and provision of mosquito nets, folic acid, and oral prophylactic penicillin, every 3 months through 5 years of age. Although the pilot program provided pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, this is now publicly available for all Angolan children, and these costs were not included. The cost of a single dose of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine ($35) was included, as this is not a standard vaccine for children in Angola. Supplies were priced according to actual costs incurred using in-country vendors. Except for a few supplies carried over at the onset of the program, all equipment and supplies were sourced locally.

Given the novelty of and expertise to implement NBS in Africa, the pilot program required foreign personnel to assist with program development. Cost of foreign personnel was not included as they are assumed to not be an integral part of its continuation, but as a subset of roles were considered essential, we did include the estimated cost of employing Angolans with similar qualifications. The pilot program used an internet-based database with servers located in the US, primarily for research and reporting progress to the project sponsor. US-based technology costs were not included, but essential information technology infrastructure and personnel in Luanda were included. Per WHO-CHOICE methodology and because of the lack of data on the costs and utilization of the healthcare system by patients with SCA, estimates of downstream medical costs were not included. Advanced laboratory tests, such as a complete blood count or reticulocyte counts, are not routinely measured and were not included.

Projection of Health Gain

To determine the health effect of NBS and treatment in Luanda, we quantified the simultaneous effects of decreased mortality and increased morbidity (inherent in longer survival) among patients with SCA. Disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) are 2 metrics that quantify mortality and morbidity simultaneously, but neither is ideal for CEA. Death results in no further accumulation of QALYs and/or a loss of DALYs equivalent to life expectancy at time of death. The latter generally is done with respect to a global standard life table. DALYs calculate morbidity using disability weights (DWs) ranging from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (equivalent to death). QALYs are the inverse, relying on a range of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores from 1 (perfect health) to 0 (equivalent to death) to quantify morbidity. A year lived in perfect health will, thus, result in 1 QALY gained and 0 DALYs lost.

The WHO-CHOICE manual recommends researchers either calculate “QALYs gained” or “DALYs averted,” but specifies that for CEA purposes, DALY-based methods should not use a reference life table because population-level interventions can affect overall life expectancy estimates. The manual further states, “For CEA, full health is valued at 1, with 0 representing the worse possible state of health, in this case death.”20 The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) Study 2010 has provided an analytic method for calculating DALYs, including DWs for SCA-related health states.23 Unfortunately, there is no internationally comparable set of HRQoL scores. We, therefore, calculated health improvements in Luanda using a metric called healthy life-years (HLYs) gained, did not use a reference life table, and approximated HRQoL scores as 1-DW from the GBD 2010 Study. HLYs gained is intended to distinguish this metric from both QALYs gained and DALYs averted, but still convey that we yet value full health at 1 rather than 0.

Estimates of Decreased Mortality

There are no definitive data to estimate current life expectancy for those Angolans with SCA or the long-term benefits of early diagnosis and treatment. We developed several survival scenarios using a wide array of data and mortality estimates derived separately from the GBD Study 2010 and the Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data Repository life tables. The GBD 2010 Study is a rigorous multi-institutional epidemiologic assessment of all diseases and injuries with specific analyses for 187 countries.24,25 The GHO Data Repository used country-specific data from the WHO to represent best estimates of mortality and burden of diseases.26 The 2 data sources have different mortality assumptions, and the use of both sources allows for a comprehensive assessment of potential survival benefits of NBS based upon available data.

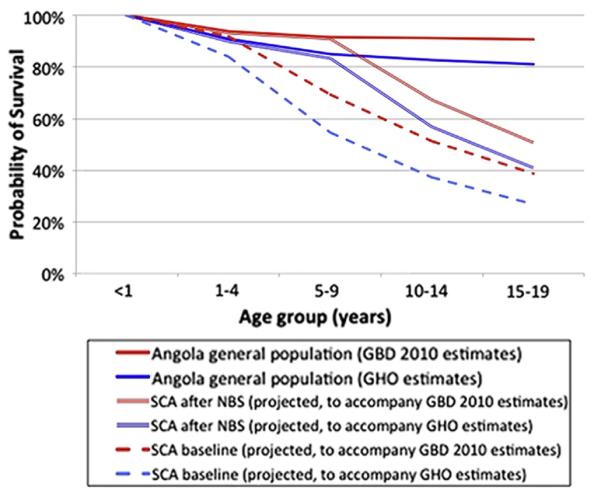

Life tables were generated for 3 groups using both GBD 2010 and GHO data: (1) all Angolan children (without consideration of SCA status); (2) Angolan children with SCA; and (3) Angolan children with SCA diagnosed by NBS. For the base scenario, we assumed that with NBS and associated clinical care: (1) the mortality for infants less than 5 years of age with SCA is improved to that of the general population of Angolan children; and (2) there is no survival benefit past age 5 years. That scenario is supported by the short-term outcomes of the pilot program.11 A second, more conservative scenario assumed that excess mortality in infancy is eliminated, that excess mortality relative to other Angolan children between ages 1 and 9 years is reduced by 50% and mortality is unchanged past age 9 years.

Estimates of Increased Morbidity in Survivors

Additional disability was assumed to occur in patients with SCA who survived as a result of this intervention, the same as for all survivors with SCA. This made our overall estimate of HLYs smaller relative to the number of life-years saved. HRQoL scores were approximated as 1 minus DW from the GBD Study 2010 for individuals with SCA and moderate anemia.23 Reflecting the combined disability associated with repeated vaso-occlusive events leading to pain crises, acute chest syndrome, splenic sequestration, and stroke, the estimated mean DW increased with age, from 0.109 at age 0-4 years to 0.237 for adults age 40 years and over.

Discounting

As per WHO-CHOICE methodology,20 we discounted both costs and health effects in future years at 3% per annum for the base case model. Because some argue that health outcomes should either not be discounted or discounted at a lower rate than costs, we performed sensitivity analyses in which health effects were discounted at a rate of 0% and costs at 6%.

Results

A total of 550 infants (1.51%) were identified with SCA over the first 23 months of the pilot NBS program.11 For the purposes of this analysis, 505 age-eligible (greater than 8 weeks) infants were used, the age at which infants were first contacted to enter clinical care. Of these 505 infants, 274 (54%) were successfully contacted. Excluding infants who died in the neonatal period (n = 11), families who refused care (n = 7), infants with confirmatory tests not consistent with the initial diagnosis (n = 10), and families who moved from Luanda (n = 2), 244 infants ultimately were brought into care. Once infants were enrolled in the clinic, continuity of care was 96.8%, with only 8 patients “lost to follow-up” for various reasons.11

The actual number of patients compliant with follow-up (236) was used for all CEA calculations. Patients defined as being compliant with follow-up included those who presented to the clinic within 6 months of the data analysis and excluded those who actively withdrew from care at the clinic for various reasons. Although some of the infants diagnosed by NBS but not successfully contacted later presented to care with clinical symptoms, treatment costs for these infants were not included in this analysis, as the purpose of CEA is to identify which costs and outcomes differ because an intervention is delivered and the infants presumably would have been treated for their symptoms in the absence of NBS. Figure 1 illustrates estimated survival of Angolan children with and without SCA, with and without NBS.

Figure 1.

Survival of infants with SCA in Angola with and without the availability of NBS and treatment are not known.

Cost of NBS and Follow-Up Care

The Table provides a detailed summary of the costs of NBS and treatment in this pilot program, including both undiscounted and discounted calculations. The total cost to screen 36 453 infants and to treat 236 infants for 5 years, including medications, training, and clinical staff is estimated to be $1 707 654. Discounting costs at 3% results in a discounted program cost of $1 610 565. For purposes of the sensitivity analysis, a 6% discounting rate was used, resulting in discounted program cost of $1 525 618.

Table.

Summary of NBS and treatment costs

| Cost of screening and testing 36 453 infants over 23 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost with 3% discounting |

Cost with 6% discounting |

||||

| Total cost, I$ (no discounting) | Per infant | Total | Per infant | Total | |

| Collection supplies | 141 208 | 3.82 | 139 241 | 3.77 | 137 385 |

| Maternity hospital labor costs | 129 594 | 3.50 | 127 789 | 3.46 | 126 086 |

| Specimen transport | 22 896 | 0.62 | 22 577 | 0.61 | 22 276 |

| Laboratory personnel | 171 717 | 4.65 | 169 325 | 4.58 | 167 069 |

| Laboratory reagents/supplies | 88 366 | 2.39 | 87 135 | 2.36 | 85 974 |

| Equipment (annualized cost) | 13 913 | 0.38 | 13 720 | 0.37 | 13 537 |

| Total screening costs | 567 694 | 15.36 | 559 787 | 15.15 | 552 327 |

|

Treatment costs for 236 children with SCA through age 5 years

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost, I$ (no discounting) | Cost with 3% discounting | Cost with 6% discounting | |

| Clinic personnel | 719 941 | 663 618 | 614 681 |

| Medications, laboratories, and treatments |

83 901 | 77 337 | 71 634 |

| Physical space, information technology, and overhead |

336 118 | 309 823 | 286 976 |

| Total treatment costs | 1 139 960 | 1 050 778 | 973 291 |

|

| |||

| Total cost of NBS and treatment (no discounting): $1 707 654 | |||

| Total cost of NBS and treatment (3%): $1 610 565 | |||

| Total cost of NBS and treatment (6%): $1 525 618 | |||

CEA

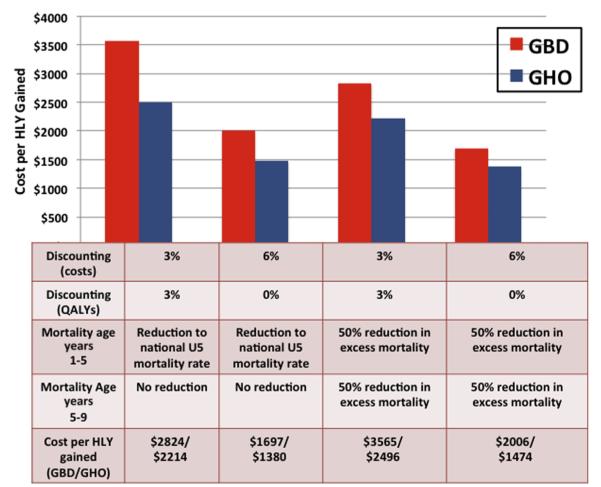

Using life tables generated from the GBD Study 2010 data, a 3% discount rate, and the different mortality assumptions previously discussed, NBS and treatment is projected to result in the gain of 452-570 HLYs. The sensitivity analysis, using a 0% discounting rate for health effects and 6% discounting of costs, projects that 760-899 HLYs will be gained. The corresponding estimated cost per HLY gained is in the range of $1697 to $3565. Calculations based on GHO data using the same discounting rates and assumptions result in similar projections (gain of 645-1105 HLYs; cost per HLY gained $1380-$2496). Figure 2 demonstrates the range of expected gains in HLYs according to the various assumptions and datasets used.

Figure 2.

Two datasets were used for the purposes of estimating mortality and HLYs gained by NBS. Given lack of precise data regarding follow-up or mortality, 4 scenarios were used to estimate the cost per HLY-gained by NBS and treatment. NBS and treatment appears to be highly cost-effective regardless of which assumptions or datasets used, with an estimated cost per HLY gained of $1380-$3565.

Discussion

Our analyses demonstrate that the cost per HLY gained for NBS and treatment in Luanda ($1380-$3565) is lower than the annual per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in Angola ($5701). The results of this study, therefore, indicate that NBS for SCA is a highly cost-effective intervention in the resource-limited setting of Luanda, Angola. As suggested by the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, interventions are considered “highly cost-effective” if the cost per DALY averted (or HLY gained) is less than per capita GDP, and “cost effective” if less than 3 times the per capita GDP.27

Data on the survival of children with SCA, with and without NBS, are lacking in Angola. This analysis used several assumptions about mortality and the survival benefits of NBS and treatment with an attempt not to overstate the possible survival benefits of NBS and treatment. Although there are no data from Africa, reports from the US, United Kingdom, and Jamaica demonstrate the survival benefits for children with SCA identified by NBS, although it is difficult to extract the specific benefits of NBS, preventive care, and acute clinical care.5-8,28,29 Our model indicates that NBS and simple preventive treatments are highly cost-effective across all scenarios, regardless of which mortality assumptions or datasets were used. Compared with the US, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios are greater for NBS in Angola. This is due to the high prevalance of SCA among newborns, the higher early mortality associated with late diagnosis, and the lower cost of healthcare personnel in Angola. No reference can be made to CEAs of other health interventions in Angola because no other published studies of this type have been identified.

Few studies have documented the cost of providing medical care to children with SCA in Africa. The annual cost of care per patient in this cohort in Luanda is approximately I$1000. In Kenya, the annual cost of caring for a child with SCA in a rural hospital outpatient clinic was reported to be approximately $150.30 Annual labor cost for the Kilifi clinic in Kenya, roughly $31 000,30 is much lower than in the Luanda clinic, approximately I$144 000 (Table), or $95 000 using the market exchange rate (results not reported). The high price level in Angola resulting from a petroleum-dominated economy leads to relatively high salaries compared with most African countries. It is important not to extrapolate data from another setting but to collect locally relevant cost information.

There are several limitations to a study of this nature. First, because our analysis calculated HLYs gained instead of DALYs averted, it is likely that our results appear less cost-effective. DALYs averted is based on a global standard life table for deaths averted, which tends to exaggerate the health gain in high mortality settings such as Angola. On the other hand, the framework of the Global Burden of Disease methodology is ideal for these types of analyses, so additional comparable literature is likely to be forthcoming. Second, our study accounts for the development of initial laboratory capacity, the program was fortunate enough to expand the care already provided in a pre-existing pediatric sickle cell clinic. This may have resulted in systematically underestimated costs and/or overestimated laboratory efficiency. For locations where there is no existing sickle cell clinic or trained staff, it will be important to incorporate the cost of building such capacity to comprehensively assess the costs of developing a NBS and treatment program in these settings. Third, our analysis was based on the percentage of contacted families whose babies completed follow-up. Unfortunately, given the limited resources of the pilot program and the difficulties faced in Luanda, just over one-half of the babies identified by NBS as having SCA were located and brought into clinical care. With improved resources and more concentrated efforts to locate affected infants, the survival benefits and cost-effectiveness of NBS may be even more pronounced than this analysis suggests. Fourth, although each step of the treatment process was performed by Angolan staff, the program was heavily supported by a US academic partner. Although the pilot program improved capacity within Angola, the transition of the overall program toward a totally Angolan program has been challenging and is still in progress. Cost estimates for Angolan personnel to replace crucial foreign staff also are somewhat speculative and may be low. Finally, our assumption could be challenged that the IT infrastructure based in the US was not required for the operation of the program and was not critical to the operations of the screening and treatment program. This assumption would underestimate cost.

In addition, the frequency and cost of health care utilization for acute complications of SCA were not included in this analysis, as per the WHO-CHOICE methodology. However, children with SCA who survive the newborn period are likely to have high utilization of the healthcare system, which will result in increased healthcare costs. Data regarding the frequency or cost of acute care utilization were not available for this patient population, as acute care was received primarily at local health centers or in the emergency departments, which both have separate record keeping systems from the sickle cell clinic. It will be critical to evaluate the frequency and cost of emergency and inpatient care to further describe the overall cost and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive sickle cell care throughout childhood.

Extrapolation of these Angolan data to other African countries should be done with caution, as each country has a unique economy and healthcare system with variable per capita health expenditure, local healthcare costs, and variable mortality rates. It will be critical to obtain local cost data and to show that the health benefits of NBS and treatment are reproducible in different settings.

Overall, mortality rates in sub-Saharan African infants under 5 years of age have fallen over the past 2 decades, primarily because of targeted efforts against vaccine-preventable diseases, HIV/AIDS, diarrhea, and malaria.31-33 SCA is a tremendously under-recognized public health challenge that has been estimated to contribute up to 5% of under 5-year mortality on the African continent. It is likely that the survival of infants with SCA will improve through universal public health efforts such as pneumococcal immunization, but the significant contribution of SCA to childhood mortality remains largely unaddressed because of lack of recognition of the scale of the problem. Based on this analysis, NBS and preventive care for SCA in the resource-limited setting of Luanda is both feasible and highly cost-effective. Universal NBS and access to early preventive care should be considered in the development of national healthcare strategies within sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Angolan Ministry of Health and the First Lady of Angola for the initial vision and support for this newborn screening program. We also are thankful to the administrative and leadership support from the Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative, Texas Children’s Global Health Initiative, and the Texas Children’s Hematology Center. The program would not be possible without the hard work of the countless local Angolan contributors to the program, including those at the maternity hospitals, laboratory, and sickle cell clinic. Most importantly, the authors are indebted for the resiliency and commitment of the Angolan patients and families, who demonstrate such a remarkable dedication to improving the health of their babies.

Funding for this pilot newborn screening program was provided by Chevron.

Glossary

- CEA

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- CHOICE

Choosing interventions that are cost-effective

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life-year

- DW

Disability weight

- GBD

Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors

- GDP

Gross domestic product

- GHO

Global Health Observatory

- HLY

Healthy life-year

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- I$

International dollars

- NBS

Newborn screening

- QALY

Quality-adjusted life year

- SCA

Sickle cell anemia

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M, et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet. 2013;381:142–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61229-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming AF, Storey J, Molineaux L, Iroko EA, Attai ED. Abnormal haemoglobins in the Sudan savanna of Nigeria. I. Prevalence of haemoglobins and relationships between sickle cell trait, malaria and survival. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:161–72. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1979.11687243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosse SD, Odame I, Atrash HK, Amendah DD, Piel FB, Williams TN. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:S398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. Global Burden of Sickle Cell Anaemia in Children under Five, 2010-2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLoS Med. 2014;10:e1001484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telfer P, Coen P, Chakravorty S, Wilkey O, Evans J, Newell H, et al. Clinical outcomes in children with sickle cell disease living in England: a neonatal cohort in East London. Haematologica. 2007;92:905–12. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115:3447–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosse SD, Atrash HK, Odame I, Amendah D, Piel FB, Williams TN. The Jamaican historical experience of the impact of educational interventions on sickle cell disease child mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:e101–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King L, Fraser R, Forbes M, Grindley M, Ali S, Reid M. Newborn sickle cell disease screening: the Jamaican experience (1995-2006) J Med Screen. 2007;14:117–22. doi: 10.1258/096914107782066185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panepinto JA, Magid D, Rewers MJ, Lane PA. Universal versus targeted screening of infants for sickle cell disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Pediatr. 2000;136:201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosse SD, Olney RS, Baily MA. The cost effectiveness of universal versus selective newborn screening for sickle cell disease in the US and the UK: a critique. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2005;4:239–47. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200504040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGann PT, Ferris MG, Ramamurthy U, Santos B, de Oliveira V, Bernardino L, et al. A prospective newborn screening and treatment program for sickle cell anemia in Luanda, Angola. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:984–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odunvbun ME, Okolo AA, Rahimy CM. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in a Nigerian hospital. Public Health. 2008;122:1111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahimy MC, Gangbo A, Ahouignan G, Alihonou E. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in the Republic of Benin. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:46–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.059113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tshilolo L, Aissi LM, Lukusa D, Kinsiama C, Wembonyama S, Gulbis B, et al. Neonatal screening for sickle cell anaemia in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: experience from a pioneer project on 31 204 newborns. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:35–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.058958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tshilolo L, Kafando E, Sawadogo M, Cotton F, Vertongen F, Ferster A, et al. Neonatal screening and clinical care programmes for sickle cell disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons from pilot studies. Public Health. 2008;122:933–41. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohene-Frempong K, Oduro J, Tetteh H, Nkrumah F. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease in Ghana. Pediatrics. 2008;121:120–1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Sickle-cell anaemia: report by the Secretariat. 59th World Health Assembly; Geneva. April 24, 2006.2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa Sickle-cell disease: a strategy for the WHO African Region: report of the Regional Director. AFR/RC60/8. Jun, 2010.

- 19.Ware RE. Is sickle cell anemia a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Geneva: [Accessed February 14, 2015]. 2003. http://www.who.int/choice/publications/p_2003_generalised_cea.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Bank [Accessed February 14, 2015];Official Exchange Rate. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF.

- 22.World Bank [Accessed February 14, 2015];PPP Conversion factor (GDP) to market exchange rate ratio. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPPC.RF.

- 23.Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR, Gagnon M, Naghavi M, Mokdad A, et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2129–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61680-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Flaxman AD, Lim S, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al. GBD 2010: design, definitions, and metrics. Lancet. 2012;380:2063–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . WHO Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Geneva: [Accessed February 14, 2015]. 2012. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Commission on Macroeconomics and Health . Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortality among children with sickle cell disease identified by newborn screening during 1990-1994—California, Illinois, and New York. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Liu G, Caggana M, Kennedy J, Zimmerman R, Oyeku SO, et al. Mortality of New York children with sickle cell disease identified through newborn screening. Genet Med. 2015;17:452–9. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amendah DD, Mukamah G, Komba A, Ndila C, Williams TN. Routine Paediatric Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) Outpatient Care in a Rural Kenyan Hospital: utilization and costs. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill K, You D, Inoue M, Oestergaard MZ, Technical Advisory Group of United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation Child mortality estimation: accelerated progress in reducing global child mortality, 1990-2010. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]