Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate accuracy of two established administrative methods of identifying children with sepsis using a medical record review reference standard.

Study design

Multicenter retrospective study at six US children’s hospitals. Subjects were children >60 days and <19 years of age were identified in four groups based on ICD9-CM codes: (1) Severe sepsis/septic shock (Sepsis Codes); (2) Infection plus organ dysfunction (Combination Codes); (3) Subjects without codes for infection, organ dysfunction, or severe sepsis; and (4) Infection but not severe sepsis or organ dysfunction. Combination codes were allowed, but not required within the Sepsis Codes group. We determined the presence of reference standard severe sepsis according to consensus criteria. Logistic regression was performed to determine whether addition of codes for sepsis therapies improved case identification.

Results

130 of 432 subjects met reference standard definition of severe sepsis. Sepsis codes had sensitivity 73% (95% CI 70–86), specificity 92% (95% CI 87–95), and positive predictive value (PPV) 79% (95% CI 70–86). Combination codes had sensitivity 15% (95% CI 9–22), specificity 71% (95% CI 65–76), and PPV 18% (95% CI 11–27). Slight improvements in model characteristics were observed when codes for vasoactive medications and endotracheal intubation were added to sepsis codes (c-statistic 0.83 vs. 0.87, p=0.008).

Conclusions

Sepsis specific ICD9-CM codes identify pediatric patients with severe sepsis in administrative data more accurately than a combination of codes for infection plus organ dysfunction.

Keywords: Septic Shock, Epidemiology

Pediatric sepsis syndrome is a leading source of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in children in the United States.(1) Accurate estimates of pediatric sepsis epidemiology are essential to ensure appropriate resource allocation, and develop appropriate benchmarking metrics. To generate these estimates, investigators have relied on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) codes to identify cases of pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock in large administrative databases.(4–8)

Reliance on ICD9-CM codes poses challenges (9). We recently reported differing mortality estimates in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock when two established ICD9-CM based coding methodologies were used to identify patients with sepsis.(9) In this prior study, subjects identified using sepsis-specific ICD9-CM codes developed in 2003 for severe sepsis (995.92) and septic shock (785.52) had 2.5 fold higher mortality compared with subjects identified using ICD9-CM codes for infection combined with codes for organ dysfunction.(9) Similar findings have been reported in adults.(10)

The accuracy of these ICD-9-CM coding strategies to identify pediatric patients with severe sepsis or septic shock as defined by international consensus definitions is not known. It is also unclear if additional elements available in administrative data sets could improve upon current ICD9-CM based strategies. In adults with sepsis, a model that included demographics, comorbidities, and treatments in the first two days of hospitalization; which compared favorably with consensus definitions.(11) Similar algorithmic analyses have proven useful in other pediatric illnesses such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection.(12, 13) Our objectives were to assess the performance of ICD9-CM coding strategies to identify severe sepsis and septic shock as defined by international consensus criteria.

Methods

This multicenter retrospective study used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database to identify children from six tertiary care, freestanding children’s hospitals. The institutional review board at each hospital approved the study.

Patients were randomly selected if they were aged >60 days to < 19 years, were admitted to a participating hospital from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2012, and met criteria for one of four study groups: 2 groups with ICD9-CM based sepsis codes, and 2 control groups. The sepsis code groups were: (1) patients with ICD9-CM codes for severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), (Sepsis Codes group); and (2) patients with ICD9-CM codes for infection plus organ dysfunction as has been previously published(5, 7, 8) (Combination Codes group; Table I available at www.jpeds.com). Because the diagnosis of severe sepsis or septic shock is reliant upon having infection and organ dysfunction, combination codes were allowed within the Sepsis Codes group. However, for the Combination Code patients, in order to specifically test the accuracy of combination codes in the absence of sepsis specific codes, sepsis code patients were excluded from this group. ICD9-CM codes were taken from hospital discharge diagnoses. Control groups were: 1) patients without ICD-9-CM codes for sepsis, infection, or organ dysfunction matched by date of hospital admission to cases in the Sepsis Codes group (Control group 1); and 2) patients with ICD-9-CM codes for infection but not organ dysfunction who were matched to cases in the Sepsis Code group by intensive care or inpatient floor admission status (Control group 2). Because we were concerned that classification of children that died may be different, we employed a stratified sampling scheme, sampling mortalities to non-mortalities at a rate that would preserve the mortality rate in each group. We based our sample size on the positive predictive value (PPV) of sepsis ICD9-CM codes. With an assumption of a PPV of sepsis codes of 75%, to achieve a 95% confidence interval with a half width of 0.05, each of the four groups required 100 subjects. Infants <61 days were excluded.

Table 1.

ICD-9 CM codes used to identify infection and organ dysfunction.

| ICD-9-CM codes for infection | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM Codea | Description |

| 001 | Cholera |

| 002 | Typhoid/paratyphoid fever |

| 003 | Other salmonella infection |

| 004 | Shigellosis |

| 005 | Other food poisoning |

| 008 | Intestingal infection not otherwise classified |

| 009 | Ill-defined intestinal infection |

| 010 | Primary tuberculosis infection |

| 011 | Pulmonary tuberculosis |

| 012 | Other respiratory tuberculosis |

| 013 | Central nervous system tuberculosis |

| 014 | Intestinal tuberculosis |

| 015 | Tuberculosis of bone and joint |

| 016 | Genitourinary tuberculosis |

| 017 | Tuberculosis not otherwise classified |

| 018 | Miliary tuberculosis |

| 020 | Plague |

| 021 | Tularemia |

| 022 | Anthrax |

| 023 | Brucellosis |

| 024 | Glanders |

| 025 | Melioidosis |

| 026 | Rat-bite fever |

| 027 | Other bacterial zoonoses |

| 030 | Leprosy |

| 031 | Other mycobacterial disease |

| 032 | Diphtheria |

| 033 | Whooping cough |

| 034 | Streptococcal throat/scarlet fever |

| 035 | Erysipelas |

| 036 | Meningococcal infection |

| 037 | Tetanus |

| 038 | Septicemia |

| 039 | Actinomycotic infections |

| 040 | Other bacterial diseases |

| 041 | Bacterial infection in other diseases not otherwise specified |

| 090 | Congenital syphilis |

| 091 | Early symptomatic syphilis |

| 092 | Early syphilis latent |

| 093 | Cardiovascular syphilis |

| 094 | neurosyphilis |

| 095 | Other late symptomatic syphilis |

| 096 | Late syphilis latent |

| 097 | Other and unspecified syphilis |

| 098 | Gonococcal infections |

| 100 | Leptosprosis |

| 101 | Vincent’s angina |

| 102 | Yaws |

| 103 | Pinta |

| 104 | Other spirochetal infection |

| 110 | Dermatophytosis |

| 111 | Dermatomycosis not otherwise classified or specified |

| 112 | Candidiasis |

| 114 | Coccidioidomycosis |

| 115 | Histoplasmosis |

| 116 | Blastomycotic infection |

| 117 | Other mycoses |

| 118 | Opportunistic mycoses |

| 320 | Bacterial meningitis |

| 322 | Meningitis, unspecified |

| 324 | Central nervous system abscess |

| 325 | Phlebitis of intracranial sinus |

| 420 | Acute pericarditis |

| 421 | Acute or subacute endocarditis |

| 451 | Thrombophlebitis |

| 461 | Acute sinusitis |

| 462 | Acute pharyngitis |

| 463 | Acute tonsillitis |

| 464 | Acute laryngitis/tracheitis |

| 465 | Acute upper respiratory infection of multiple sites/not otherwise specified |

| 481 | Pneumococcal pneumonia |

| 482 | Other bacterial pneumonia |

| 485 | Bronchopneumonia with organism not otherwise specified |

| 486 | Pneumonia, organism not otherwise specified |

| 491.21 | Acute exacerbation of obstructive chronic bronchitis |

| 494 | Bronchiectasis |

| 510 | Empyema |

| 513 | Lung/mediastinum abscess |

| 540 | Acute appendicitis |

| 541 | Appendicitis not otherwise specified |

| 542 | Other appendicitis |

| 562.01 | Diverticulitis of small intestine without hemorrhage |

| 562.03 | Diverticulitis of small intestine with hemorrhage |

| 562.11 | Diverticulitis of colon without hemorrhage |

| 562.13 | Diverticulitis of colon with hemorrhage |

| 556 | Anal and rectal abscess |

| 567 | Peritonitis |

| 569.5 | Intestinal abscess |

| 569.83 | Perforation of intestine |

| 572 | Abscess of liver |

| 572.1 | Portal pyemia |

| 575.0 | Acute cholecystitis |

| 590 | Kidney infection |

| 597 | Urethritis/urethral syndrome |

| 599.0 | Urinary tract infection not otherwise specified |

| 601 | Prostatic inflammation |

| 614 | Female pelvic inflammation disease |

| 615 | Uterine inflammatory disease |

| 616 | Other female genital inflammation |

| 681 | Cellulitis, finger/toe |

| 682 | Other cellulitis or abscess |

| 683 | Acute lymphadenitis |

| 686 | Other local skin infection |

| 711.0 | Pyogenic arthritis |

| 730 | Osteomyelitis |

| 790.7 | Bacteremia |

| 996.6 | Infection or inflammation of device/graft |

| 998.5 | Postoperative infection |

| 999.3 | Infectious complication of medical care not otherwise classified |

| ICD-9-CM codes used to identify organ dysfunction | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM Codea | Description |

| 785.5 | Shock without trauma |

| 458 | Hypotension |

| 96.7 | Mechanical ventilation |

| 348.3 | Encephalopathy |

| 293 | Transient organic psychosis |

| 348.1 | Anoxic brain damage |

| 287.4 | Secondary thrombocytopenia |

| 287.5 | Thrombocytopenia, unspecified |

| 286.9 | Other/unspecified coagulation defect |

| 286.6 | Defibrination syndrome |

| 570 | Acute and subacute necrosis of liver |

| 573.4 | Hepatic infarction |

| 584 | Acute renal failure |

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Where 3 or 4 digit codes are listed, all associated subcodes were included

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Where 3 or 4 digit codes are listed, all associated subcodes were included

There were two data sources used for this study: the PHIS database and medical record review. The PHIS database, which contains clinical and billing data for 44 tertiary care children’s hospitals, was used to identify participants. Data quality processes have been described elsewhere. (14) Medical record data were extracted by trained investigators, at each site, blinded to study group assignment, and entered into a web-based data collection system.(15) The reference standard was severe sepsis or septic shock as defined by International Consensus Criteria based on detailed medical record review.(3) Severe sepsis was present if subjects had vital signs and white blood cell count which qualified them for the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), concern for infection defined as the presence of clinical testing for an infectious source (bacterial testing, viral testing, or radiographic studies specifically to evaluate for infection), and evidence of at least two organ system dysfunctions or the presence of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in the absence of cardiovascular dysfunction as previously defined.(3) Septic shock was defined as SIRS plus concern for infection and cardiovascular dysfunction. We conducted two sensitivity analyses with more inclusive reference standards: 1) SIRS, concern for infection, and evidence of at least one organ system dysfunction, and 2) removing the requirement for fluid resuscitation prior to assessment of cardiovascular function. Training to apply consensus sepsis definitions was provided during pre-study conference calls. Each site conducted pilot testing of the instrument, and changes were made by consensus to ensure common understanding. At sites with more than one reviewer, 2 investigators reviewed 3 pilot cases in full and achieved 100% agreement in sepsis severity determination prior to the beginning of full chart abstraction. Medical record review followed this process: the entire hospitalization was reviewed to determine an “event day,” the first day of the most severe category of septic shock, severe sepsis, sepsis, or concern for infection. If none were present, the day with the most abnormal vital signs was chosen. Data abstraction was then limited to the “event day” and the following hospital day. At sites with more than 1 reviewer, both reviewed 10% of records, and agreement was determined by Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance. Biweekly conference calls allowed discussion of de-identified cases with questionable application of consensus definitions and final determination was by consensus.

Data Analyses

Summary statistics used proportions for categorical variables and median and interquartile range for continuous variables. Comparisons used chi-squared tests for categorical and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. To determine the performance of each ICD9-CM based identification strategy for sepsis, we calculated PPVs utilizing the reference standard outcome. To determine whether we could improve Sepsis Code performance, we selected a priori administrative variables associated with sepsis diagnosis and care (Table II; available at www.jpeds.com) Candidates were generated from a random forest that included indicator variables for every ICD-9 diagnosis code, procedure code, lab, image, and pharmaceutical. One thousand conditional inference trees were fit to bootstrap samples, and aggregated by averaging observation weights. Conditional variable importance was used to select candidate variables. This was performed using the ‘Party’ package for R v.3.2.(16–18) We tested the association of these variables with the reference standard using logistic regression.(19) Subjects were randomly allocated into derivation (80%) and validation (20%) groups. Statistics other than model development were performed using SAS v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and p-values<0.05 were considered significant.

Table 2.

The potential list of candidates for the multivariable model in Table 3 was generated from a random forest model. Candidate variables for inclusion in the multivariable model were generated from a random forest that included indicator variables shown above for every ICD-9 diagnosis code, procedure code, lab, image, and pharmaceutical. 1000 conditional inference trees were fit to bootstrap samples, and aggregated by averaging the observation weights. Conditional variable importance was used to select candidate variables. This was performed using the ‘Party’ package for R v.3.2.

| Factors Considered for model | |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 120000 Anti-infective agents |

| Fluids | 146218 Sodium Chloride |

| Blood products | 99.04 transfusion of pRBC 99.05 transfusion of platelets 99.06 transfusion of coagulation factors 99.08 transfusion of blood expander |

| Vasoactive Agents | 131311 dopamine 131305 dobutamine 131321 epinephrine 131111 milrinone 131351 norepinephrine |

| Infectious testing | 361100 Bacterial cultures, unspecified (includes aerobic and anaerobic from any source) 361200 Bacterial test, unspecified (antibody and PCR based tests 362000 Yeast and fungi, unspecified 363000 Parasites, unspecified 364000 Viruses, unspecified |

| Other lab testing (Lactate, Blood Gas) | 313300 Lactate 311100 Blood gas |

| Radiology | 87.44 Chest X-ray |

| Procedures | |

| 38.91 arterial catheterization | |

| 38.97 central venous catheter placement with guidance | |

| 39.65 ECMO | |

| 89.61 systemic arterial pressure monitoring | |

| 89.62 central venous pressure monitoring | |

| 93.90 non-invasive mechanical ventilation | |

| 96.70–96.72 continuous invasive mechanical ventilation | |

| 96.04 insertion of endotracheal tube | |

| Diagnoses | |

| 995.92 Severe sepsis | |

| 785.52 Septic shock | |

| 038.9 Unspecified septicemia | |

| 287.5 Thrombocytopenia, unspecified | |

| 518.81 Acute respiratory failure | |

| 276.2 Acidosis | |

| 276.69 Other fluid overload | |

| 255.41 Glucocorticoid deficiency |

Results

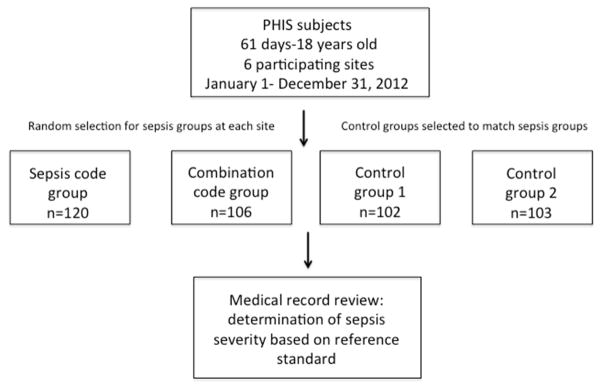

A total of 431 medical records were randomly selected from across the six sites with 120 patients from the sepsis-specific ICD-9-CM (Sepsis Code) group, 106 patients from the combined infection plus organ dysfunction ICD-9-CM (Combination Code) group, 102 from control group 1, and 103 from control group 2 (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). Of the 130 subjects who met international consensus criteria (i.e. the reference standard) for severe sepsis or septic shock, 95 had ICD9-CM codes for severe sepsis or septic shock (sepsis codes), 19 had ICD9-CM codes for infection plus organ dysfunction (combination codes), and 16 had neither ICD9-CM codes for sepsis nor for infection plus organ dysfunction. There were no significant differences between the Sepsis Code group, Combination Code group, and control groups with regards to sex, race, or payor. There were differences between the four groups with regards to age distribution, presence of complex chronic conditions, and hospital length of stay (Table III). Kendall coefficient of concordance was performed on 10% of records at sites with more than one reviewer to determine consistency of medical record review and was 0.87 for sepsis severity as compared with reference standard determination. Concordance for additional organ dysfunction determination is shown in Table IV (available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure. Schema of study process.

Sepsis code group is subjects with ICD9-CM codes for severe sepsis or septic shock. Combination code group is subjects with ICD9-CM codes for infection plus organ dysfunction. Control group 1 is subjects without ICD9-CM codes for sepsis, infection, or organ dysfunction matched to sepsis code subjects on date of hospital admission. Control group 2 is subjects with ICD9-CM codes for infection but not sepsis or organ dysfunction matched to the sepsis code group based on admission status to the intensive care unit or regular inpatient floor. Medical record review was performed blind to group assignment.

Table 3.

Demographics of study groups. Sepsis Code gro up patients had ICD9-CM codes for severe seps is or septic shock. Combination Code group patients had ICD9-CM codes for infection plus organ dysfunction. Control group 1 patients did not have codes for sepsis, infection, or organ dysfunction and were matched to Sepsis Code patients on date of hospital admission. Control group 2 had ICD9-CM codes for infection but not sepsis or organ dysfunction, and were matched to Sepsis Code patients on proportion admitted to the intensive care unit vs. regular inpatient floor. Use of mechanical ventilation and vasoactive medications are on the sepsis day only. For length of stay variables, the median is presented with interquartile range in brackets.

| N(%) | Total | Sepsis Codes | Combination Codes | Control Group 1 | Control Group 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Patients | 431 | 120 | 106 | 102 | 103 | |

| Female | 196 (45.5) | 53 (44.2) | 55 (51.9) | 41 (40.2) | 47 (45.6) | 0.394 |

| Age | ||||||

| 61d–<1 year | 83 (19.3) | 17 (14.2) | 25 (23.6) | 10 (9.8) | 31 (30.1) | 0.005 |

| 1 year–4 years | 130 (30.2) | 38 (31.7) | 27 (25.5) | 38 (37.3) | 27 (26.2) | |

| 5 years–9 years | 81 (18.8) | 21 (17.5) | 22 (20.8) | 26 (25.5) | 12 (11.7) | |

| 10 years–14 years | 61 (14.2) | 22 (18.3) | 11 (10.4) | 16 (15.7) | 12 (11.7) | |

| 15–<19 years | 76 (17.6) | 22 (18.3) | 21 (19.8) | 12 (11.8) | 21 (20.4) | |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 258 (59.9) | 71 (59.2) | 65 (61.3) | 58 (56.9) | 64 (62.1) | 0.753 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 64 (14.8) | 16 (13.3) | 14 (13.2) | 19 (18.6) | 15 (14.6) | |

| Hispanic | 60 (13.9) | 18 (15) | 11 (10.4) | 17 (16.7) | 14 (13.6) | |

| Asian | 10 (2.3) | 4 (3.3) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Other | 39 (9) | 11 (9.2) | 13 (12.3) | 8 (7.8) | 7 (6.8) | |

| Payor | ||||||

| Government | 204 (47.3) | 63 (52.5) | 52 (49.1) | 43 (42.2) | 46 (44.7) | 0.667 |

| Private | 186 (43.2) | 45 (37.5) | 44 (41.5) | 51 (50) | 46 (44.7) | |

| Other | 41 (9.5) | 12 (10) | 10 (9.4) | 8 (7.8) | 11 (10.7) | |

| Any comorbidity | 314 (72.9) | 94 (78.3) | 92 (86.8) | 50 (49) | 78 (75.7) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay | 6 [3, 16] | 14 [6, 30] | 11 [5, 29] | 4 [2, 7] | 4 [3, 7] | <.001 |

| Reference standard sepsis | 130 (30.2) | 95 (79.2) | 19 (17.9) | 8 (7.8) | 8 (7.8) | <.001 |

| ICU admission | 300 (69.6) | 108 (90) | 59 (55.7) | 30 (29.4) | 103 (100) | <.001 |

| Mortality | 25 (5.8) | 18 (15) | 5 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 167 (38.7) | 75 (62.5) | 55 (51.9) | 11 (10.8) | 26 (25.2) | <.001 |

| Vasoactive medications | 85 (19.7) | 71 (59.2) | 10 (9.4) | 1 (1) | 3 (2.9) | <.001 |

Table 4.

Kendall’s coefficient of correlation and percent agreement for organ dysfunction determination in 10% of medical records reviewed by 2 investigators

| Kendall’s coefficient of correlation | % Agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Dysfunction | 69.7 | 91.3 |

| ARDS | 100 | 100 |

| Respiratory Dysfunction | 77.6 | 95.7 |

| Hematologic Dysfunction | 100 | 100 |

| Neurologic Dysfunction | 100 | 100 |

| Renal Dysfunction | 100 | 100 |

| Hepatic Dysfunction | 100 | 100 |

| Sepsis Severity Categorization | 68.9 | 82.6 |

Sepsis Codes had the following test characteristics: sensitivity 73% (95% CI 70–86), specificity 92% (95% CI 87–95), and positive predictive value (PPV) 79% (95% CI 70–86). Combination Codes had sensitivity 15% (95% CI 9–22), specificity 71% (95% CI 65–76), and PPV 18% (95% CI 11–27; Table V). Test characteristics of each identification method using a more inclusive reference standard for severe sepsis (SIRS + concern for infection + at least 1 organ system dysfunction) are also reported in Table V. We also determined that a small proportion (6%) of the study sample had either hypotension or vasoactive medication utilization without receiving 40 ml/kg of fluid and qualified as septic shock using the Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) reference standard. We have reported the test characteristics by study site in Table VI (available at www.jpeds.com). Although we were not powered to determine difference in diagnostic code performance by site, Sepsis Codes had higher PPV, sensitivity, and specificity than Combination Codes for the reference standard at all sites.

Table 5.

Accuracy measures of each identification method compared to the reference standard.In the upper panel, reference standard was severe sepsis or septic shock as defined by international consensus criteria. Positive predictive value (PPV), sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio positive, and area under the ROC curve (AUROC) are presented. In the lower panel, reference standard was defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome vital signs, suspected infection and at least one organ dysfunction defined by Goldstein criteria.

| Reference Standard: SIRS + infection + 2 organ dysfunctions OR ARDS OR CV dysfunction | ICD9 Codes Utilized | Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock by Chart Review | PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio+ (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification Method | Yes | No | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 95 | 25 | 79 (70, 86) | 73 (64, 80) | 92 (87, 95) | 8.8 (5.1, 12.4) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 19 | 87 | 18 (11, 27) | 15 (9, 22) | 71 (65, 76) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.6) |

| Control group 1 | Infection no organ dysfunction | 8 | 94 | 8 (2, 13) | 6 (2, 12) | 69 (63, 74) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) |

| Control group 2 | No sepsis, infection, or organ dysfunction | 8 | 95 | 8 (2, 13) | 6 (2, 12) | 68 ( 62, 74) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) |

| Reference Standard: SIRS + infection + at least 1 organ dysfunction | ICD9 Codes Utilized | Sepsis Defined as Infection + 1 organ | PPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio+ (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 96 | 24 | 80 (71, 87) | 54 (46, 62) | 91 (86, 94) | 5.7 (3.2, 8.2) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 42 | 64 | 40 (30, 50) | 24 (17, 31) | 75 (69, 80) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) |

| Control group 1 | Infection no organ dysfunction | 18 | 84 | 18 (10, 25) | 10 (6, 16) | 67 (60, 73) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) |

| Control group 2 | No sepsis, infection, or organ dysfunction | 21 | 82 | 20 (13, 29) | 12 (7, 18) | 68 (61, 73) | 0.4 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) |

Table 6.

.Test characteristics of sepsis codes and combination codes by study site.

| Identification Method | ICD9 Codes Utilized | Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock by Chart Review | PPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Site 1 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 14 | 6 | 70 (49, 90) | 52 (33, 71) | 87 (76, 97) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 11 | 7 | 39 (16, 61) | 26 (9, 42) | 76 (63, 88) |

| Site 2 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 16 | 4 | 80 (62, 98) | 70 (50, 88) | 92 (84, 99) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 3 | 15 | 17 (0, 34) | 13 (0, 27) | 69 (56, 82) |

| Site 3 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 16 | 4 | 80 (62, 98) | 73 (54, 91) | 92 (84, 99) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 2 | 15 | 12 (0, 27) | 9 (0, 21) | 69 (55, 82) |

| Site 4 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 19 | 1 | 95 (85, 100) | 86 (72, 100) | 98 (94, 100) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 1 | 16 | 6 (0, 17) | 5 (0, 13) | 68 (55, 81) |

| Site 5 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 17 | 3 | 85 (69, 100) | 89 (75, 100) | 94 (88, 100) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 2 | 16 | 11 (0, 26) | 11 (0, 24) | 70 (57, 82) |

| Site 6 | ||||||

| Sepsis Codes | Severe sepsis/Septic Shock | 13 | 7 | 65 (44, 86) | 76 (56, 97) | 88 (79, 96) |

| Combination Codes | Infection + organ dysfunction | 4 | 14 | 22 (3, 41) | 24 (3, 44) | 75 (64, 86) |

In the base model using only diagnostic codes, the presence of a severe sepsis ICD9-CM (995.92) code was strongly associated with reference standard for severe sepsis or septic shock (OR 28.8 [95% CI 15.6–53.1]; Table VII). Because all subjects with an ICD9-CM code for septic shock (785.52) also had a code for severe sepsis (995.92), the septic shock code was not included in the model as a separate variable. We then added the predetermined administrative sepsis care variables (Table II) to assess improvement in performance of the model. In the adjusted model, the severe sepsis code (995.92) remained the strongest association with the outcome (OR 21.8, (95% CI 11.1–42.6)). Model performance improved slightly (c-statistic increased from 0.83 to 0.87, p=0.008) with the addition codes for administration of vasoactive agents and insertion of an endotracheal tube (Table VII). Test characteristics for reference standard sepsis determination using the model with administrative plus billing data for case identification are also shown in Table VII.

Table 7.

Logistic regression modelsto evaluate the association between sepsis ICD9-CM codes and reference standard sepsis. The base model considered ICD9-CM diagnostic codes. Candidate variables were determined by a random forest and included intravenous antibiotics, intravenous fluid boluses, bacterial testing, vasoactive medications, endotracheal tube insertion, and glucocorticoid deficiency. Variables with significant association are included in this table. Details of considered variable codes are listed in Table 2, online. The bottom row of data represents test characteristics of using the regression model to identifying reference standard severe sepsis/septic shock cases.

| Logistic regression model | AOR (95% CI) | p | C Statistic | Improvement over Base Model | ||||

| Base Model | ||||||||

| Severe sepsis (995.92) | 28.8 (15.6, 53.1) | <0.001 | Derivation: 0.83 Validation: 0.80 |

|||||

| Model Using Administrative and Billing Data | ||||||||

| Infectious testing | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.028 | Derivation: 0.87 Validation: 0.91 |

p<0.001 | ||||

| Severe sepsis (995.92) | 21.8 (11.1, 42.6) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Vasoactive Agents | 3.0 (1.3, 7.1) | 0.008 | ||||||

| Insertion of endotracheal tube (96.04) | 3.5 (1.4, 8.4) | 0.006 | ||||||

| Test characteristics of model using administrative plus biiling data | ICD9 Codes Utilized | Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock by Chart Review | PPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | Likelihood Ratio+ | AUROC | |

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Sepsis codes + vasoactive med codes + endotracheal tube placement codes | Model codes above | 86 | 34 | 72 (63, 80) | 80 (72, 87) | 86 (81, 90) | 5.7 (3.7, 7.7) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) |

Discussion

We found that sepsis specific ICD9-CM codes identified pediatric patients with severe sepsis or septic shock based on a strict reference standard in an administrative data set more accurately than a combination of ICD9-CM codes for infection plus organ dysfunction. We have previously shown important differences in pediatric severe sepsis prevalence, resource utilization, and outcomes in two cohorts of patients identified using these distinct ICD9-CM based identification strategies. (9) Taken together, our previous and current study indicate that the true mortality rate for pediatric sepsis is likely closer to the higher mortality rate found in patients identified using sepsis codes as opposed to the lower rate found using combination codes (21.2% vs. 8.2%). We found that over 80% of subjects identified using the combination code method did not have severe sepsis or septic shock as determined by medical record review, raising concerns that epidemiologic studies using this method may be overestimating severe sepsis prevalence and underestimating resource utilization and mortality.

We also evaluated if components of sepsis care available in administrative data would improve the accuracy of sepsis codes alone to identify pediatric patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Although we found a small benefit of adding administrative codes for vasoactive medications and endotracheal tube insertion, the most predictive element in our model was the ICD9-CM code for severe sepsis, 995.92. This code was not yet available when the Combination Code strategy was developed.(8, 9) Use of the Combination Code strategy may explain the lower mortality rates in the previously described populations. We were interested to find that adding codes for infectious testing decreased the accuracy of the model (AOR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1, 0.9), although the upper bound of the 95% CI was close to 1. We feel that this is most likely due to the fact that infectious testing is sent on a wide variety of patients, many of whom do not have severe sepsis.

There are several limitations to this study. First, there may be temporal trends in diagnostic coding for sepsis that we did not identify given the one year study period. Second, there may be misclassification bias to identification of patients with sepsis using ICD9-CM based identification algorithms. In order to identify patients with reference standard sepsis that did not have an ICD9-CM code related to sepsis or organ dysfunction, we selected two groups of control patients: one in which we attempted to enrich for possible sepsis patients by including patients in the intensive care unit with ICD9-CM codes for infection but not sepsis or organ dysfunction, as well as a second control group of patients who were matched to case patients based on date of hospital admission. In addition, we masked reviewers to group assignment to decrease any potential for systemic bias. Third, the generalizability of our findings may be limited as study sites were academic children’s hospitals, and it is possible that sepsis coding practices are different than at general community hospitals. Future studies using a nationally representative patient sample would help to address these concerns. Fourth, we utilized as our reference standard the definitions of severe sepsis determined by Goldstein(3), which require either dysfunction of 2 organ systems or cardiovascular dysfunction or ARDS alone to meet criteria for severe sepsis or septic shock. It is possible that we could have found different results had we used more inclusive definitions of severe sepsis/septic shock. To address these possibilities, we performed two sensitivity analyses with more liberal reference definitions and found similar results. Finally, we do not know how the remapping of ICD-9 to ICD-10 codes will influence the accuracy of sepsis coding; results from this study may not be applicable.

It is critical to point out that although we demonstrate that ICD-9 sepsis codes are more accurate than infection plus organ dysfunction combination codes, the test characteristics determined in this study highlight the challenges of identifying sepsis patients using administrative data alone. Despite these challenges, the ability to utilize administrative data to describe trends in pediatric sepsis is critically important, particularly given the growing national spotlight on sepsis care. Our findings will allow more accurate assessment of pediatric sepsis epidemiology, resource utilization, and outcomes using administrative data. These estimates are essential to facilitate equitable distribution of resources, assignment of research priorities, and uniform benchmarking of quality metrics across geographic regions and health care systems.

Acknowledgments

F.B. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K12-HL109009). SW was supported by NIH/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K12-HD047349) and NIH/the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (K23-GM110496). P.B. was supported by career development support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08-HS023827).

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- ICD9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- ICD-10

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision

- kg

Kilogram

- ml

Milliliter

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- OR

Odds ratio

- PALS

Pediatric Advanced Life Support

- PHIS

Pediatric Health Information System

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SIRS

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

- US

United States

Footnotes

Reprints will not be requested

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Vital Statistics System, Natioanl Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Apr;29:530–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005 Jan;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart A, Stegman M, Ford B, editors. International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification. 6. Salt Lake City: OptumInsight, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Lidicker J, Angus DC. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Mar 1;167:695–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odetola FO, Gebremariam A, Freed GL. Patient and hospital correlates of clinical outcomes and resource utilization in severe pediatric sepsis. Pediatrics. 2007 Mar;119:487–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Watson RS. Trends in the Epidemiology of Pediatric Severe Sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013 Jul 26; doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182917fad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul;29:1303–10. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss SL, Parker B, Bullock ME, Swartz S, Price C, Wainwright MD, Goodman DM. Defining pediatric sepsis by different criteria: discrepancies in populations and implications for clinical practice. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e219–26. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823c98da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Neuman MI, Scott H, Brady PW, Paul R, et al. Pediatric Severe Sepsis in U.S. Children’s Hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014 Aug 26; doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the Incidence and Mortality of Severe Sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013 Mar 15; doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagu T, Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Nathanson BH, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, et al. Development and validation of a model that uses enhanced administrative data to predict mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2011 Nov;39:2425–30. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822572e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tieder JS, Hall M, Auger KA, Hain PD, Jerardi KE, Myers AL, et al. Accuracy of administrative billing codes to detect urinary tract infection hospitalizations. Pediatrics. 2011 Aug;128:323–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DJ, Shah SS, Myers A, Hall M, Auger K, Queen MA, et al. Identifying pediatric community-acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: Accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Sep;167:851–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongelluzzo J, Mohamad Z, Ten Have TR, Shah SS. Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2008 May 7;299:2048–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breiman L. Random Forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hothorn T, Lausen B, Benner A, Radespiel-Troger M. Bagging survival trees. Stat Med. 2004 Jan 15;23:77–91. doi: 10.1002/sim.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strobl C, Boulesteix AL, Kneib T, Augustin T, Zeileis A. Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988 Sep;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CHCA sepsis quality improvement collaborative. 2012 Available from: extranet.chca.com/CHCAforums/PerformanceImprovement/Colalboratives/Sepsis.

- 21.Paul R, Neuman MI, Monuteaux MC, Melendez E. Adherence to PALS Sepsis Guidelines and Hospital Length of Stay. Pediatrics. 2012 Jul 2; doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]