Abstract

Objectives

Increased erythrocytic osmotic fragility and splenomegaly have been reported in anemic Abyssinian and Somali cats. Here we report on this condition in anemic domestic shorthair cats and two other breeds, and describe common features of the clinicopathological profiles, management and outcomes.

Methods

Anemic cats, other than Abyssinians and Somalis, were included. The erythrocytic osmotic fragility test was performed, known causes of anemia were excluded, the illness was followed and medical records were reviewed.

Results

Twelve neutered cats were first found to be anemic between 0.5 and 9.0 years of age. Pallor, lethargy, inappetence, pica, weight loss and splenomegaly were commonly observed. A moderate-to-severe macrocytic and hypochromic anemia with variable regeneration was noted. Infectious disease screening, direct Coombs’ and pyruvate kinase DNA mutation test results were negative. Freshly drawn blood did not appear hemolysed but became progressively lysed during storage at 4°C. The sigmoid osmotic fragility curves were moderately to severely right shifted, indicating erythrocytic fragility at 20°C. Cross-correction studies indicated an intrinsic red cell effect rather than plasma effect. Most cats were treated with immunosuppressive doses of prednisolone and doxycycline, with variable responses. Five cats with recurrent or persistent anemia responded well to splenectomy. However, two had occasional recurrence of severe anemia: one was found to be Bartonella vinsonii-positive during one episode and responded to azithromycin and prednisolone, while the other cat had two episodes of severe anemia of unknown cause. Finally, six cats were euthanized within 1 month and 7 years after initial presentation. Histopathology of six spleens revealed mainly congestion and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Conclusions and relevance

Similarly to Abyssinian and Somali cats, domestic shorthair and cats of other breeds can also develop severe erythrocytic osmotic fragility with anemia and splenomegaly, which should be considered as a differential diagnosis in anemic cats.

Introduction

The erythrocytic osmotic fragility (OF) test estimates the surface area to volume ratio of erythrocytes, and is used to measure red blood cell (RBC) fragility in cases of chronic or recurring anemia. 1 Briefly, whole blood is incubated in isotonic-to-hypotonic sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions at 20°C. As water is drawn into RBCs during exposure to progressively hypotonic solutions, the RBCs swell, leak and then burst. The hemoglobin (Hb) released into the supernatant is assessed spectrophotometrically and is expressed as the percentage of the completely lysed blood in distilled water. The normal OF curve is sigmoid, and the mean OF (MOF; NaCl concentration at which 50% of RBCs lyzed) occurs around 0.5% NaCl in healthy animals. Generally, the OF is inversely related to the normal size of RBCs in animal species. 2

In humans, an abnormal erythrocytic OF test result may suggest hereditary RBC membrane defects such as spherocytosis and stomatocytosis, 3 but is also observed with some acquired disorders such as renal failure, diabetes mellitus and immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA).1,3 Nowadays, the OF test is rarely conducted in human medicine and has been replaced by more specific tests, such as ektacytometry, protein electrophoresis, Coombs’ test and DNA tests for hereditary RBC membrane defects. 3 Increased OF has also been reported in dogs with hereditary spectrin deficiency,4,5 hereditary stomatocytosis,5–9 IMHA10,11 and other anemias. 12

Increased OF has also been documented in cats with IMHA, 13 and in Abyssinian and Somali cats, which may have a hereditary erythrocyte membrane defect. 14 In the latter, fragile RBCs were accompanied by chronic intermittent hemolytic, macrocytic–hypochromic and variably regenerative anemia, splenomegaly, hyperglobulinemia, lymphocytosis, hyperbilirubinemia and increased serum hepatic enzyme activities. Here we report on increased erythrocytic OF in anemic domestic shorthair (DSH) cats and purebred cats with clinicopathological features similar to those previously reported in Somali and Abyssinian cats.

Material and methods

Animals and samples

Client-owned cats other than Abyssinians and Somalis that were diagnosed with chronic or intermittent anemia of unknown cause, had negative infectious disease screening and direct Coombs’ test results by the primary or referring veterinarian, which revealed increased fragility in a requested erythrocytic OF test by the PennGen Laboratory (PennGen, University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA) between September 2009 and September 2014, were included. Fresh EDTA anticoagulated blood samples (2–4 ml) were either collected at the Ryan Veterinary Hospital (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA), or submitted by the referring veterinarian along with a sample from a healthy cat (frequently a donor cat that needed blood typing or other screening tests) by overnight shipping. Additional control blood samples were obtained from healthy cats from a research colony at the University of Pennsylvania. All samples were sent and kept refrigerated at 4°C and analyzed simultaneously on the same or the following day. The study was performed according to the Guidelines for the Institutional Care and Use of Animals in Research.

Signalment and medical records, including history, physical examination, clinicopathological information and therapeutic interventions taken at the first diagnosis of anemia, were reviewed. Cats were followed after initial diagnosis of increased OF when possible.

Laboratory tests

Routine laboratory tests utilized for this analysis, including complete blood count, reticulocyte count, packed cell volume (PCV), total protein, microscopic blood smear evaluation, serum chemistry panel and urinalysis, were performed at the same time or shortly before the first OF test. All of these tests were performed either by the primary clinic, their reference laboratories (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME, USA, or Antech, Irvine, CA, USA) or the clinical laboratory of the Ryan Veterinary Hospital.

A direct Coombs’ test was performed at 37°C using regular commercial reagents (IgG, IgM, C3) by the reference laboratory utilized by the submitting clinic; a follow-up test (Antiglobulin Feline Test; Alvedia) at 20ºC, which has not yet been independently validated, was also performed by PennGen. Similarly, feline blood typing and pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency DNA testing was performed at PennGen.15,16

All cats were tested for feline leukemia virus (FeLV) antigen and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) antibodies by SNAP test (IDEXX) and hemoplasma (Mycoplasma haemofelis, Mycoplasma haemominutum, Mycoplasma turicensis) by PCR. Other infectious disease screening tests (NCSU, Vector Borne Disease Lab, Raleigh, NC, USA) performed in some cats included antibody screening for Bartonella species using an immunofluorescence assay and/or Western blot (National Veterinary Laboratory, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and PCR testing for Anaplasma, Babesia, Bartonella, Ehrlichia, hemoplasma, Rickettsia and Cytauxzoon species.

Abdominal imaging, histopathology and cytology

Abdominal imaging studies were evaluated when performed. Gross and histopathological or cytological findings of the spleen, liver and bone marrow were reviewed, when necropsied, removed, biopsied and/or aspirated.

Erythrocytic in vitro lysis and OF test

The PCV, whole blood and plasma Hb concentrations were measured (B-Hemoglobin HemoCue) 17 to assess in vivo and in vitro lysis of samples at the time of receipt (freshly drawn or after shipping and chilled overnight) and again the next day after storage at 4°C.

The OF test was performed as previously described by this laboratory,10,14 with minor modifications from the original assay. 18 Anticoagulated blood from patients and corresponding healthy control cats were processed simultaneously. Briefly, a series of phosphate-buffered NaCl dilutions was prepared, containing concentrations of 0.85, 0.8, 0.75, 0.7, 0.65, 0.6, 0.55, 0.5, 0.45, 0.4, 0.35, 0.25 and 0% NaCl. Two milliliters of each solution was mixed well with 15 µl of whole blood in individual test tubes. After 30–45 mins of incubation at 20°C, samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 mins. The optical densities of the supernatants were measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm and the percentage of hemolysis of each tube was calculated. The MOF was determined from the obtained lysis curve.

Cross-correction testing

In order to differentiate between intrinsic (RBC) and extrinsic (plasma) issues, RBCs and plasma from each cat were simultaneously incubated separately with the reciprocal components from the healthy control cat. Briefly, after centrifuging ~0.5 ml EDTA blood at 1000 g for 3 mins, the plasma was transferred into another tube, while the RBCs were suspended in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then centrifuged again. Washing with PBS was repeated twice to remove all plasma.

Aliquots (~0.2 ml) of washed RBCs from the affected cat and its healthy control were then incubated at 4°C with aliquots (0.2–0.3 ml) of plasma from the control cat and from the affected cat, respectively. After 6 and 24 h incubation, OF tests were performed with both sample combinations and the unwashed original blood samples at 20°C.

Analysis and statistics

Following data acquisition by Microsoft Excel 2013, standard statistical analyses were applied (SPSS Statistics 22; IBM). Data were tested for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed parametric data were calculated as mean ± SD and non-normally distributed data as median (range). The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was performed to test the paired MOF results, from affected and control cats in OF testing and the cross-correction studies. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Animals

In total, 12 cats, including ten DSH cats, one Ocicat and one Siamese cat, all neutered and privately owned in different parts of the USA, exhibiting chronic or intermittent anemia and increased erythrocytic OF were included in this study (Table 1). Nine DSH cats were adopted from shelters or found as stray cats, while the others (cats 2, 3 and 7) were obtained from breeders. All cats were kept indoors, fed a commercial cat food and, according to the owners, were never exposed to any known toxins. Eight animals lived with at least one other cat in the same household, and one also with dogs. The cats’ coat colors varied, but four were tricolored, cream diluted tabby DSH cats from Southwestern Pennsylvania (Table 1); their estimated birth dates ranged from 2006–2011. According to the owners, the Ocicat and one DSH cat (cat 11) had littermates and other relatives with anemia of unknown cause, but those were not further studied.

Table 1.

Clinical details of the cats with increased osmotic fragility (OF), including treatment, additional tests and clinical course

| Cat | Sex | Age at first anemia (years) | Age when OF tested (years) | Additional infectious disease screen | Doxy-cycline | Predni-solone | pRBC events (n) | Relapses postmedication | Spleen ultrasound findings | Age at splenectomy (years) | Relapses postsplenectomy | Histopathology spleen (S)/ liver (L) | Current age/age at death (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* † | F | 1.5 | 2.5 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | – | Four in 2 years | Mottled, nodules | 4.5 | 0 | S | 6.75 |

| 2 | M | 2 | 2.75 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | – | Two in 0.66 years | Mottled | 2.75 | 0 | S/L | 3.25 |

| 3 ‡ | M | 4.25 | 4.5 | Yes | Yes | 1 | No improvement | Not done | 4.5 | 0 | S | 5.75 | |

| 4* † | F | 2.25 | 2.5 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | – | One after 0.5 years | Normal echotexture | 3 | Two after 3 years within 0.5 years | S | 6.75 |

| 5 | M | 2 | 5.25 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Two in 3.25 years | Granular | 5.25 | Two after 2 years within 2 years | S | Euthanized at 9 | |

| 6* † | F | 2 | 3 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Two in 1.25 years | Mottled | No | – | 3.5 | ||

| 7 § | M | 4 | 4 | – | Yes | – | None, doing well | Normal echotexture | No | – | 4.75 | ||

| 8* † | F | 7.5 | 7.5 | Bartonella Western blot | – | Yes | 2 | One after 0.75 years | Nodules | No | – | Euthanized at 8.5 | |

| 9 | F | 0.5 | 0.6 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | 1 | No improvement | Not done | No | – | Euthanized at 0.6 | |

| 10 † | F | 9 | 9 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | 6 | No improvement | Mottled, nodules | No | – | S/L | Euthanized at 9 |

| 11 | F | 0.5 | 0.65 | Bartonella Western blot | Yes | – | – | One after 0.5 years | Not done | No | – | L | Euthanized at 1 |

| 12 | M | 1.5 | 2 | Vector-borne disease panel | Yes | Yes | – | One after 0.5 years | Mottled | No | – | Euthanized at 2 |

Vector-borne disease panel: PCR for Anaplasma, Babesia, Bartonella, Ehrlichia, hemoplasma, Rickettsia and Cytauxzoon species, and immunofluorescence and/or Western blot assay for Bartonella species. ‘Yes’ refers to medication received or test performed

Dilute cream tabby cats

Cases presented at University of Pennsylvania

Ocicat

Siamese

pRBC = packed red blood cell transfusion; F = female; M = male

Clinical signs and routine test results

Pallor (n = 11), lethargy (n = 8) and splenomegaly (n = 11) were the main clinical signs at presentation. Weight loss (n = 5), inappetence (n = 6) and pica (n = 5) were also observed. Three of the dilute-colored cats had increased body condition scores (BCS) ranging between 6 and 8 (normal BCS 5/9). One additional DSH cat (cat 2) with black fur also had an increased BCS of 8, but none had hyperlipidemia on presentation. First anemia was found between 0.5 and 9.0 years of age (median 2.25 years).

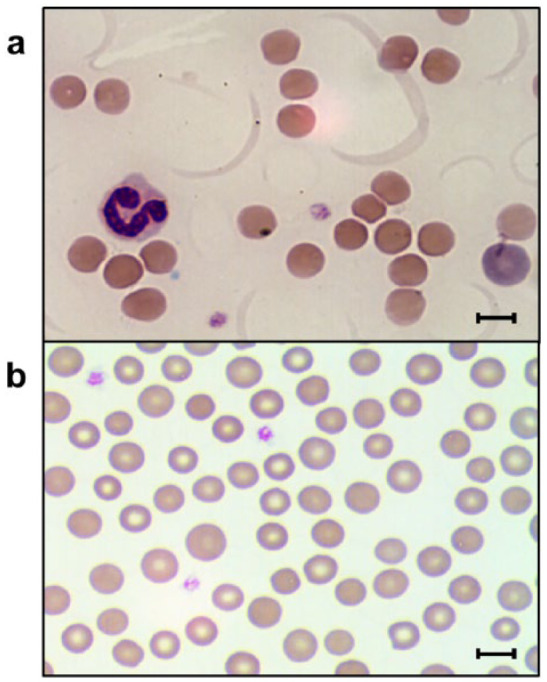

All cats had a history of chronic or intermittent anemia before the OF test was performed (Tables 1 and 2). They were found to be anemic with a wide range of hematocrit values, which also fluctuated greatly over time. Common RBC characteristics at the initial time of OF testing were moderate-to-marked macrocytosis (n = 9), mild hypochromasia (n = 5), mild-to-marked anisocytosis (n = 10; Figure 1), polychromasia (n = 8) and reticulocytosis (n = 7). If these characteristics were not noted initially, they were found at later examinations. Moreover, in seven cats, few-to-many normoblasts were seen on blood smear examination. Low or moderate numbers of Heinz bodies and Howell–Jolly bodies were also found in four and three cats, respectively.

Table 2.

Selected hematology and chemistry panel results from all 12 cats with increased osmotic fragility at initial examination

| Parameter | Mean ± SD or median | Range | Reference interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCT (%) | 20.3 ± 7.1 | 6.9–26.0 | 31.7–48.0 |

| RBCs (×106/µl) | 3.4 ± 1.4 | 1.0–5.5 | 6.6–11.2 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 6.31 ± 2.26 | 2.1–9.6 | 10.6–15.6 |

| MCV (fl) | 63.5 ± 12.3 | 43.0–79.0 | 36.7–53.7 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 30.9 ± 2.6 | 27.9–38.3 | 30.1–35.6 |

| Reticulocytes (×103/µl) | 130 | 12–666 | 0–50 |

| nRBCs (/100 WBC) | 3 | 0–126 | 0–1 |

| WBCs (×103/µl) | 12.7 | 4.6–40.7 | 4.0–18.7 |

| Serum bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6 | 0.2–6.9 | 0.1–0.4 |

HCT = hematocrit; RBC = red blood cell; Hb = hemoglobin; MCV = mean cell volume;

MCHC = mean cell hemoglobin concentration; nRBC = nucleated red blood cell; WBC = white blood cell

Figure 1.

Blood smears from two cats with increased osmotic fragility showing (a,b) anisocytosis and (a) polychromasia (bar = 6 µm)

Total white blood cell counts of 11 cats were within the reference interval (RI), except cat 12 (Tables 1 and 2), which had a severe neutrophilia (39.6 ×103/µl; RI 2.3–14.0 ×103/µl) with normal cell morphology. Rare reactive lymphocytes were initially observed on the blood smears of three cats, but were also seen in four additional cats at later examinations.

Urinalysis and serum chemistry results were normal, except that five cats had mild hyperbilirubinemia and cat 12 had marked hyperbilirubinemia. Cat 12 also had elevated serum liver enzyme activities: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 401 U/l (RI 33–152 U/l) and aspartate aminotransferase was 349 U/l (RI 1–37 U/l).

Serum iron concentrations measured in cats 2 and 4 were normal. Direct Coombs’ test and PK deficiency DNA test results were negative in all cats.

All animals were negative for FeLV, FIV and hemoplasma infections. Additionally, six cats tested negative for the available entire vector-borne feline infectious disease panel by PCR and serology, and two cats were serologically negative for Bartonella species infections by Western blot (Table 1). Cat 4 was later found to be serologically strongly positive for Bartonella vinsonii (see below).

Abdominal imaging, histopathology and cytology findings

Abdominal ultrasound performed on nine cats showed mild-to-severe splenomegaly with varied changes; three (cats 5, 6 and 8) also had mild hepatomegaly (Table 1).

Histopathological examination of splenic samples from splenectomy (n = 5) and necropsy (n = 1) revealed marked congestion (n = 5), mild-to-moderate extramedullary hematopoiesis (n = 5), mild hemosiderosis (n = 3), mild scattered lymphoid follicles (n = 1) and scattered clusters of macrophages (2) (Table 1). Hepatic samples from one wedge biopsy and two necropsies showed moderate extramedullary hematopoiesis (n = 2), histiocytosis (n = 1) and marked hemosiderosis (n = 1). One bone marrow aspirate (cat 10) revealed mild erythroid hyperplasia and focal megakaryocytic hyperplasia, while the other seemed unremarkable (cat 5).

Erythrocytic in vitro lysis and OF test results

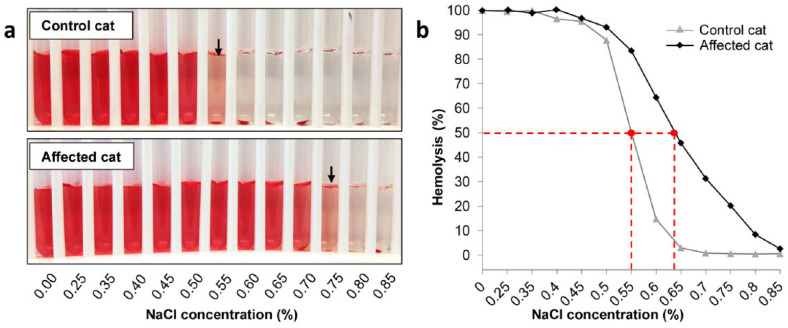

While little to no hemolysis was observed at the time of blood collection, moderate-to-severe in vitro hemolysis (plasma Hb 0.8–5.5 g/dl) was observed in 8/10 EDTA blood samples evaluated after 6 and 24 h stored at 4°C (Figure 2). Simultaneously handled control blood samples revealed little to no hemolysis (plasma Hb ⩽0.3 g/dl) based upon visual examination of microhematocrit tubes and plasma Hb determinations.

Figure 2.

Microhematocrit results from one cat at time of blood collection and 6 and 24 h after blood collection stored at 4°C. Packed cell volume (PCV) decreased from 20% to 14% and 12%, respectively

The OF curves of the anemic cats were moderately to severely right shifted (Figure 3), with MOFs ranging from 0.63–0.87% NaCl at the time of initial testing when compared with corresponding controls, for which the MOFs ranged from 0.45–0.57% NaCl (P = 0.002). The location and shape of the OF curve either stayed as initially determined or the RBCs became even more fragile after 24 h. In two cases (cats 3 and 10) only a small proportion of RBCs resisted storage at 4°C 1 day after blood collection, making OF testing nearly impossible.

Figure 3.

Osmotic fragility (OF) test results from an affected and control cat. (a) An OF tube test result with the mean OF (MOF) is depicted with an arrow. (b) Right-shifted curve of an affected cat with increased OF and a normal curve from the corresponding control cat. The curve of the control cat has a sigmoid shape, while the affected cat’s curve is flattened and hemolysis is occurring at higher concentrations of sodium chloride. Dashed lines indicate in both curves the MOFs at 50% hemolysis

Cross-correction test results

Plasma and washed RBC components of blood samples from three DSH cats (cats 4, 6 and 11) were cross-corrected with components of their complementary control blood samples. In all three cases MOFs of RBCs from healthy control cats remained normal after incubation at 4°C with either their own plasma or plasma from the affected cats. In contrast, MOFs of RBCs from affected cats remained increased after incubation with either their own plasma or plasma from the control cats (Table 3). Thus, an intrinsic issue causing increased erythrocytic OF was suspected.

Table 3.

Osmotic fragility (OF) of erythrocytes during in vitro cross-correction experiments

| Incubation (h) | Patient RBCs + patient plasma | Patient RBCs + control plasma | Control RBCs + control plasma | Control RBCs + patient plasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.65 (0.65–0.83) | – | 0.54 (0.51–0.57) | – |

| 6 | 0.65 (0.64–0.73) | 0.62 (0.59–0.75) | 0.55 (0.51–0.55) | 0.52 (0.50–0.54) |

| 24 | 0.66 (0.65–0.76) | 0.67 (0.61–0.75) | 0.55 (0.52–0.57) | 0.53 (0.51–0.59) |

Mean OF (%) of cross-correction test results from three cats expressed as median (range)

RBC = red blood cell

Therapy and follow-up results

All cats were initially treated with doxycycline and/or immunosuppressive doses of prednisolone (1–2 mg/kg q12h) presumptively for an infectious and/or immune process, with the exception of cat 8 (Table 1). Generally, when the PCV rose the prednisolone dose was tapered stepwise every 2–4 weeks until withdrawn. Cats with persistent or recurring anemia according to routine follow-up laboratory results were continually treated or retreated with prednisolone (1–2 mg/kg q12h), splenectomized and/or euthanized. In critically ill cases of severe anemia, AB type compatible packed RBCs were transfused (Table 1). Few cats also received additional antibiotics, including amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (n = 4), enrofloxacin (n = 2), marbofloxacin (n = 1) and azithromycin (n = 1).

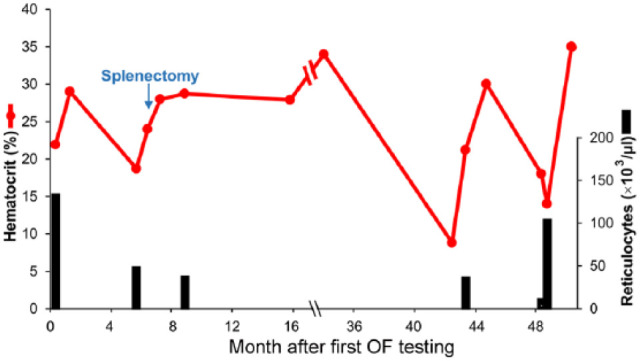

Of the five splenectomized cats, three recovered without relapse and recent follow-up OF tests were normal in these cats. Cat 4 (Table 1; Figure 4) had an episode of recurrent anemia with abnormal OF 3 years after splenectomy, and was found to be serologically positive for B vinsonii but was negative by PCR test. Rapid improvement was observed after treatment with azithromycin and prednisolone. PCR test results for Bartonella species remained negative, and the serum antibody titer against B vinsonii declined drastically over 5 months to negative. However, this cat relapsed 6 months later with severe anemia (PCV 16%) and increased OF but was completely negative for any infectious diseases and recovered well following treatment with prednisolone and azithromycin (PCV 35% for past 8 months).

Figure 4.

Clinical course in cat 4 with increased osmotic fragility (OF). Hematocrit and reticulocyte counts over a 4 year period following first OF testing

Cat 5 developed recurrent anemia of unknown cause 2 years after splenectomy, which appeared to respond well to intermittent prednisolone therapy for another 2 years, but the cat was then euthanized.

Special cases that did poorly and were not splenectomized are presented below.

Cat 8 was found to have macrocytic anemia on a routine examination and aside from routine blood work and the OF test, additional diagnostics and treatments were declined by the owner. However, 9 months later this cat developed severe anemia (PCV 9%). No cause was identified and medical emergency treatment appeared unsuccessful; the cat was euthanized.

Cat 11 was stable for 7 months with mild anemia (PCV 26%) before suddenly developing severe hyperbilirubinemia (20.1 to 25.5 mg/dl; PCV 21%) and mildly increased serum ALT activities (from 199 to 225 U/l), which appeared therapeutically unresponsive to routine emergency care. Necropsy revealed cholangiohepatitis with cholestasis, fibrosis and centrolobular atrophy.

Cat 12 showed intermittent recurring anemia over 6 months, then acutely developed non-regenerative anemia, neutrophilia, hypoproteinemia and also had elevated serum ALT activity (401 U/l) and was euthanized. No necropsy was performed.

Discussion

Anemia is a very common abnormality in cats in any clinical practice and can result from infectious, immune, toxic, metabolic and inherited causes.19,20 Here we describe a unique condition of anemia with increased erythrocytic OF and splenomegaly in DSH and purebred cats, similar to what this laboratory previously described in anemic Abyssinian and Somali cats.5,14 Prevalence and underlying cause(s) still need to be determined.

A remarkably severe in vitro fragility of erythrocytes that is not typically observed in either feline anemia or other diseases was documented in these 12 anemic cats. While hemolysis was not observed in freshly collected blood, it became apparent and progressively increased within hours to days of regular storage in an EDTA tube at 4°C. This was readily evident by visual examination of the EDTA tube and/or after centrifuging a blood sample in a microhematocrit tube and without rewarming the blood. In fact, some blood samples were nearly completely lysed by the next day, whereas the simultaneously handled, shipped and stored control samples from healthy cats showed little-to-no hemolysis during the same time frame. Such in vitro hemolysis seems to be unique to these cats and the previously reported Abyssinian and Somali cats with increased OF.5,14

Concordantly, utilization of a classic OF test demonstrated that erythrocytes from these cats were markedly more fragile in hypotonic solutions than were RBCs from healthy control cats. In fact, some erythrocytes started to lyse near physiological NaCl concentration. The OF curve was significantly shifted to the right, suggesting that all of the erythrocytes were similarly affected. They appeared to swell rapidly, even in solutions utilized for automated hematology cell counters, resulting in increased macrocytic and lysing artefacts observed during analysis. These observations are similar to those reported previously in Abyssinian and Somali cats. 14

When examining the patients’ erythrocytes and plasma separately in in vitro cross-correction experiments from three anemic cats compared with controls, it became evident that the patients’ washed erythrocytes lysed similarly in the presence of control and autologous plasma, while the controls’ erythrocytes remained stable in autologous and patient plasma. These limited data support an intrinsic RBC-related defect, and inherited or acquired erythrocyte abnormalities are suspected, but further studies are needed. Severely increased OF has been observed in Miniature and Middle Schnauzers, Alaskan Malamutes and Drentse Patrijshond with hereditary stomatocytosis, a disease assumed to be caused by a red cell membrane defect.6–9 However, the cats in this report and also in the study of Abyssinian and Somali cats had few, if any, stomatocytes, although the observed high mean cell volume was disproportional to the degree of reticulocytosis. Milder erythrocytic OF is also seen with IMHA in dogs,10–12 but has rarely been studied in cats with IMHA. 13 Despite extensive attempts to find an acquired cause, no immune, infectious (one exceptional cat was later found to have a Bartonella infection as revealed by positive serology) or toxic cause was identified over extended follow-up periods similar to the previously described Abyssinian and Somali cats. 14 Indeed, increased erythrocytic OF has been previously reported in a few cats with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, hemoplasma infection, anemia of inflammatory disease and suspected hereditary poikilocytosis.13,14,21–23 We did not find any support for these or other diseases in the cats of this report. We did not specifically prepare and examine the blood for cold antibodies and complement. Thus, we cannot entirely exclude cold agglutinin disease, cold hemolytic anemia or paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria, as reported in human patients. 24 None of the cats had any evidence of massive pigmenturia or peripheral cold agglutinin disease. Furthermore, the lysing observed in vitro at cold temperatures and increased OF seem unique to these cats.

Interestingly, four of the 12 affected stray cats from Southeastern Pennsylvania had a tricolored dilute haircoat, suggesting that perhaps they were related and therefore had a common hereditary red cell defect. While some cats, including three of the tricolored cats with dilute haircoat, were overweight, their plasma was not found to be lipemic during routine laboratory testing. Interestingly, lipemia has been associated with increased OF in different species receiving a high fat diet and also in diabetic dogs.25–29

Despite the overwhelming in vitro evidence of erythrocytic fragility in the cats of this report, the in vivo evidence of hemolysis is indirect. These cats had intermittently severe anemia but reached normal hematocrit values. There was never any evidence of blood loss, but some of the cats showed pica, which is a typical sign of blood loss with iron or other deficiencies. Based upon the lack of hemoglobinemia and hemoglobinuria, an extravascular hemolysis predominantly in the enlarged spleen appears most likely. Hemolysis was suggested by a regenerative macrocytic hypochromic anemia with mild hyperbilirubinemia and reticulocytosis. The degree of reticulocytosis varied greatly but was frequently less than what would be expected for the severity of the anemia, suggesting transient marrow issues hampering the regenerative response in these cats.

Most of the cats in this study, as well as the previous report on Abyssinian and Somali cats with increased OF, 14 had moderate-to-severe splenomegaly. Diffuse splenomegaly in cats is often associated with marked extramedullary hematopoiesis and was observed in Abyssinian and Somali cats with increased OF. Somewhat surprisingly, extramedullary hematopoiesis was not a major finding here. Splenomegaly can also occur in cats with hemoplasmosis, FeLV infection and other infectious diseases,30,31 but tests and histopathology did not reveal any infectious agents. Similarly, despite an association of anemia with hemolymphatic neoplasias in cats,30,31 there was no evidence of cancer. Splenectomy in five cats with severe episodes of anemia seemed to reduce the degree of in vitro lysis and anemia for months to years, suggesting that the spleen enhanced RBC fragility through an unknown mechanism, thereby accelerating RBC clearance. An improved OF was also observed in cats with hemoplasma infection following splenectomy. 32

Treatment of cats with immunosuppressive doses of prednisolone appeared to temporarily resolve or improve their anemia. As direct Coombs’ tests were all negative, prednisolone-mediated inhibition of RBC-specific autoantibodies is unlikely to account for the response. However, prednisolone may inhibit macrophage-mediated attack of altered RBCs and stabilize membranes. 20

The ultimate reasons for euthanasia of six cats in this study were lack of response to medical treatment and progressive decline or development of hemolytic crisis, severe icterus or recurring anemia. Interestingly, two cats with signs of hemolytic anemia also showed signs of severe primary hepatopathy and were euthanized. It is unclear at this time if the hepatopathy was related to OF in these two cats. No bilirubin calculi were found in any cats with increased OF, while in cats with PK deficiency it was occasionally observed.33,34

Conclusions

Similarly to anemic Abyssinian and Somali cats, anemic DSH and other purebred cats can develop severe OF and splenomegaly. The RBCs appeared to be extremely fragile in vitro and limited cross-correction studies support an intrinsic RBC defect in promoting increased erythrocytic OF. Many of the observed clinicopathological and histopathological features resemble those previously reported in Abyssinian and Somali cats. No acquired, immune, infectious or toxic causes could be identified. Treatment with doxycycline, prednisolone and blood transfusions may improve the clinical condition, but such responses appear transient. Splenectomy seems to be the most effective option for long-term improvement of anemia and OF, although a cure has not been achieved.

Acknowledgments

Referring clinicians are thanked for their assistance with submitting samples and providing medical record information. This study was carried out at the University of Pennsylvania, in part, as fulfillment of the doctoral thesis of Claudia Tritschler at the University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health # OD 010939.

The authors are members of the nonprofit PennGen laboratory, which offers OF and other hematological testing.

Accepted: 20 April 2015

References

- 1. Beutler E. Osmotic Fragility. In: Williams JW, Beutler E, Erslev AJ, et al. (eds). Hematology. 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Co, 1990, pp 1726–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perk K, Hort I, Perri H. The degree of swelling and osmotic resistance in hypotonic solutions of erythrocyes from various domestic animals. Refuah Vet 1964; 20: 122. [Google Scholar]

- 3. King MJ, Zanella A. Hereditary red cell membrane disorders and laboratory diagnostic testing. Int J Lab Hematol 2013; 35: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slappendel RJ, van Zwieten R, van Leeuwen M, et al. Hereditary spectrin deficiency in Golden Retriever dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19: 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giger U. Hereditary erythrocyte disorders. In: Bonagura JD, Kersey R. (eds). Kirk’s current veterinary therapy. 13th ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 1999, pp 414–420. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Slappendel RJ, van der Gaag I, van Nes JJ, et al. Familial stomatocytosis-hypertrophic gastritis (FSHG), a newly recognised disease in the dog (Drentse patrijshond). Vet Q 1991; 13: 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinkerton PH, Fletch SM, Brueckner PJ, et al. Hereditary stomatocytosis with hemolytic anemia in the dog. Blood 1974; 44: 557–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giger U, Amador A, Meyers Wallen V, et al. Stomatocytosis in miniature schnauzers [abstract]. Proc ACVIM Forum 1988: 754. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonfanti U, Comazzi S, Paltrinieri S, et al. Stomatocytosis in 7 related Standard Schnauzers. Vet Clin Pathol 2004; 33: 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caviezel LL, Raj K, Giger U. Comparison of 4 direct coombs’ test methods with polyclonal antiglobulins in anemic and nonanemic dogs for in-clinic or laboratory use. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 28: 583–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piek CJ, Junius G, Dekker A, et al. Idiopathic immune-mediated hemolytic anemia: treatment outcome and prognostic factors in 149 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paltrinieri S, Comazzi S, Agnes F. Haematological parameters and altered erythrocyte metabolism in anaemic dogs. J Comp Pathol 2000; 122: 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kohn B, Weingart C, Eckmann V, et al. Primary immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in 19 cats: diagnosis, therapy, and outcome (1998–2004). J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kohn B, Goldschmidt MH, Hohenhaus AE, et al. Anemia, splenomegaly, and increased osmotic fragility of erythrocytes in Abyssinian and Somali cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217: 1483–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seth M, Jackson KV, Giger U. Comparison of five blood-typing methods for the feline AB blood group system. Am J Vet Res 2011; 72: 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giger U, Rajpurohit Y, Wang P, et al. Molecular basis of erythrocyte pyruvate kinase (R-PK) deficiency in cats [abstract]. Blood 1997; 90 Suppl: 5b. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Callan MB, Giger U, Oakley DA, et al. Evaluation of an automated system for measurement in animals. Am J Vet Res 1992; 53: 1760–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parpart AK, Lorenz PB, Parpart ER, et al. The osmotic resistance (fragility) of human red cells. J Clin Invest 1947; 26: 636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Couto C. Anemia. In: Nelson RW, Couto CG. (eds). Small animal internal medicine. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2014, pp 1201–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giger U. Regenerative anemias caused by blood loss or hemolysis. In: Ettinger S, Feldman E. (eds). Veterinary internal medicine. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp 1886–1907. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jain NC. Osmotic fragility of erythrocytes of dogs and cats in health and in certain hematologic disorders. Cornell Vet 1973; 63: 411–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giger U, Reilly MP, Tasi A, et al. Beta-thalassemia in a cat: a naturally-occuring disease model. Blood 1994; 84: 364a. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ottenjann M, Weingart C, Arndt G, et al. Characterization of the anemia of inflammatory disease in cats with abscesses, pyothorax, or fat necrosis. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gertz MA. Management of cold haemolytic syndrome. Br J Haematol 2007; 138: 422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abdelhalim MA, Moussa SA. Biochemical changes of hemoglobin and osmotic fragility of red blood cells in high fat diet rabbits. Pak J Biol Sci 2010; 13: 73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akahane K, Furuhama K, Onodera T. Simultaneous occurrence of hypercholesterolemia and hemolytic anemia in rats fed cholesterol diet. Life Sci 1986; 39: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Behling-Kelly E, Collins-Cronkright R. Increases in beta-lipoproteins in hyperlipidemic and dyslipidemic dogs are associated with increased erythrocyte osmotic fragility. Vet Clin Pathol 2014; 43: 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooper RA, Leslie MH, Knight D, et al. Red cell cholesterol enrichment and spur cell anemia in dogs fed a cholesterol-enriched atherogenic diet. J Lipid Res 1980; 21: 1082–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sengupta A, Ghosh M. Integrity of erythrocytes of hypercholesterolemic and normocholesterolemic rats during ingestion of different structured lipids. Eur J Nutr 2011; 50: 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Couto CG. Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. In: Nelson RW, Couto CG. (eds). Small animal internal medicine. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2014, pp 1264–1275. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Autran de Morais H, O’Brien RT. Non-neoplastic diseases of the spleen. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC. (eds). Veterinary internal medicine. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp 1944–1951. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maede Y. Studies on feline haemobartonellosis. V. Role of the spleen in cats infected with Haemobartonella felis. Jpn J Vet Res 1978; 40: 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harvey AM, Holt PE, Barr FJ, et al. Treatment and long-term follow-up of extrahepatic biliary obstruction with bilirubin cholelithiasis in a Somali cat with pyruvate kinase deficiency. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 424–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Geffen C, Savary-Bataille K, Chiers K, et al. Bilirubin cholelithiasis and haemosiderosis in an anaemic pyruvate kinase-deficient Somali cat. J Small Anim Pract 2008; 49: 479–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]