Abstract

The large number of coronary artery bypass procedures necessitates development of off-the-shelf vascular grafts that do not require cell or tissue harvest from patients. However, immediate thrombus formation after implantation due to the absence of a healthy endothelium is very likely. Here we present the successful development of an Acellular Tissue Engineered Vessel (A-TEV) based on small intestinal submucosa that was functionalized sequentially with heparin and VEGF. A-TEVs were implanted into the carotid artery of an ovine model demonstrating high patency rates and significant host cell infiltration as early as one week post-implantation. At one month, a confluent and functional endothelium was present and the vascular wall showed significant infiltration of host smooth muscle cells exhibiting vascular contractility in response to vaso-agonists. After three months the endothelium aligned in the direction of flow and the medial layer comprised of circumferentially aligned smooth muscle cells. A-TEVs demonstrated high elastin and collagen content as well as impressive mechanical properties and vascular contractility comparable to native arteries. This is the first demonstration of successful endothelialization, remodeling, and development of vascular function of a cell-free vascular graft that was implanted in the arterial circulation of a pre-clinical animal model.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately a half million coronary artery bypass graft surgeries are performed annually in the United States [1]. While autologous vessels such as saphenous veins, radial, or left internal mammary arteries remain the most common and viable replacement options, limited availability of suitable autologous vessels [2, 3], morbidity at the donor site, and the high rate of long-term failure of venous grafts necessitate the search for alternative strategies [4–6]. While synthetic grafts have demonstrated impressive long-term patency rates for the replacement of large diameter arteries (>6mm), the long-term patency of small-diameter arterial replacements remains low [7–10]. To this end, tissue engineering approaches using native or synthetic scaffolds and even scaffold-free strategies have developed functional and implantable vascular grafts that have been tested in small and large animal models, as well as in human clinical trials [11–18]. However, development of such tissue engineered vessels (TEV)s typically requires the use of autologous cells, and weeks to months of cell expansion, tissue growth, and mechanical preconditioning before implantation.

As a result several laboratories have turned their attention to engineering cell-free vascular grafts using two approaches. One approach employs cell-containing TEVs, which are grown for several weeks to achieve extracellular matrix remodeling and mechanical properties necessary for successful implantation before they are decellularized to provide “off-the-shelf” transplantable grafts [19–21]. However, host cell infiltration and tissue remodeling was limited near the anastomotic sites [19] and a functional endothelium may still be necessary to maintain graft patency [14, 22]. In addition, it takes several weeks to months to prepare these tissues with concomitant logistic issues stemming from long-term culture times. The second approach employs biomaterials that are treated to prevent thrombosis and promote endothelialization [23, 24]. These grafts exhibited patency and remodeling in rats, however, it is not clear whether this approach would work in larger, clinically relevant animal models that exhibit significant differences in cardiovascular physiology and matrix recellularization patterns [25].

To address these limitations, we developed an acellular tissue engineered vessel (A-TEV) using a native biomaterial, small intestine submucosa (SIS), which was coated with heparin-bound vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to prevent thrombosis and promote endothelialization. SIS has been extensively evaluated in clinical settings, where it was shown to promote tissue remodeling and regeneration [26–29], but previous attempts to use it as an acellular vascular graft have failed [30–32]. Here we demonstrate that the presence of VEGF led to high patency rates and complete endothelialization of the SIS lumen within one month post-implantation in an adult ovine model. At the same time, we observed regeneration of the vascular wall, with high density of infiltrating host cells and extracellular matrix remodeling yielding mechanical properties that were similar to native vessels as well as development of contractile function. In summary, we developed a small diameter A-TEV and shown successful implantation into a large animal model. This signifies a major advancement in the development of clinically relevant off-the-shelf vascular grafts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Statistical Analyses

All experimental assays included a minimum of n=3 animals for each group (A-TEV 1-wk, A-TEV 1-mo, A-TEV 3-mo and native carotid). Unpaired two-tailed student t-tests were then performed on these groups and values were considered significant if the returned p value ≤0.05. No less than n=3 fields of view (for IHC) and n=3 tissue ring samples from each animal were evaluated for vascular reactivity and mechanical properties. Each animal is assigned a pattern within each time point and followed throughout the manuscript.

VEGF cloning and protein production

Bioactive, recombinant VEGF isoform 165 was produced and purified as previously described[33]. Briefly, bacteria strain Escherichia coli BL21-DE3-pLysis containing pGEX-VEGF, encoding for a thrombin cleavable glutathione-s-tranferase (GST) tag followed by the VEGF-165 gene, was induced with 1mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for protein production for 4–6hr at 37°C and 300rpm. Bacterial pellets were then lysed (50mM Tris, 500mM NaCl, 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 8.5, 1mg/mL lysozyme, and protease inhibitors) and sonicated. GST-VEGF containing inclusion bodies were then subjected to numerous rounds of washing and sonication then solubilized (50mM Tris, 500mM NaCl, 7M Urea, 1M Guanidine-HCl, 1mM EDTA, 100mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 8.5) prior to refolding by dialysis. Briefly, solubilized GST-VEGF was immediately added to a dialysis membrane (SpectraPor-1 6–8kDa cut-off) and dialyzed in 100× volume of Refolding Buffer-1 (50mM Tris, 500mM NaCl, 10mM KCl, 1mM EDTA, 2M Urea, 500mM L-Arginine, 5mM reduced glutathione, 0.5mM oxidized glutathione, pH 8.5) for 24hr, then the refolding buffer was replaced with half the urea concentration of the previous day for 72hr. The final dialysis step was performed in PBS. Refolded GST-VEGF was then subjected to sequential purification using GST agarose beads (Sigma, St. Loius, MO), thrombin cleavage of GST from VEGF, and a final purification step of Hitrap Heparin Column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburg, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Biological Activity of Recombinant VEGF

The biological activity of recombinant VEGF was assessed using a standard cell proliferation assay as previously described[33]. Briefly, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were seeded onto a 96-well plate with varying concentrations of recombinant VEGF or commercial (control) VEGF (Cell Signaling). Concentrations ranged from 0.05ng/mL to 100ng/mL. Cells were allowed to proliferate for 72hr prior to treatment with 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Life Technologies) for 4hr, followed by solubilization of the purple formazan crystals, and absorbance reading at 570nm using a Biotek Synergy 4 Spectrophotometer (with background absorbance at 650nm subtracted).

ELISA

VEGF concentration on SIS (5mm in diameter) was determined by ELISA. VEGF was detected using biotin-conjugated goat anti-VEGF antibody (100ng/mL, 2 hr, RT, R&D Systems), followed by incubation with streptavidin-HRP (1:200, 30min, RT) and addition of substrate (TMB, Sigma). Absorbance was read at 450nm using a Biotek Synergy 4 Spectrophotometer (with subtraction of background absorbance of 570nm).

Immobilization of Heparin and VEGF onto SIS

Laminated SIS tubes (4cm in length and 4.5–4.75mm diameter) were provided by Cook-Biotech Inc (West Lafayette, IN). For heparin immobilization, SIS was immersed in 10mL of 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid buffer (MES), pH 1.5, containing 20mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), 20mM N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and heparin sulfate (8000U) and gently agitated for 36hr at 37°C. SIS was then gently washed in PBS to neutralize the reaction and remove unbound heparin. Heparin concentration on SIS was determined by comparing the unbound heparin concentration remaining in solution to the initial concentration [34]. Briefly, unbound heparin was added to toluidine blue buffer (0.1mg toluidine blue dissolved in 50mM tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer, pH 4.5) at a ratio of 1 volume toluidine blue to 12 volumes heparin solution. The reaction proceeded for 30min prior to centrifugation and absorbance was measured at 631nm using a Biotek Synergy 4 Spectrophotometer (background absorbance of an empty well was subtracted from each value). To immobilize VEGF, heparin bound SIS was then immersed in 10mL of PBS with 3mg of recombinant human VEGF-165 for 8hr, washed with PBS, and either immediately implanted or analyzed. VEGF remained immobilized on the heparin surface by utilizing the heparin binding domain[35].

Release Kinetics

VEGF released from SIS was assessed using in-direct ELISA. Buffers used for release kinetics include PBS, PBS + 196U/mL heparin, PBS+ 1960U/mL heparin, and growth media (EGM2; Lonza) + 10% FBS using SIS pieces with and without immobilized heparin followed by VEGF immobilization. SIS pieces (n=8 per condition) were incubated at 37°C and 10% CO2 for a total of 120hr. At time points of 24, 48, 72, and 120 hr the buffer was replaced with fresh buffer and analyzed for VEGF concentration using ELISA (VEGF Duoset, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was read at 450nm using a Biotek Synergy 4 Spectrophotometer (with subtraction of background absorbance of 570nm). Cumulative amount of VEGF was calculated over time and normalized to the initial amount of immobilized VEGF.

Animal care and graft implantation

All animal surgical procedures and other protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the State University of New York at Buffalo. A mixed breed (Dorset cross) of female sheep, 2–4 yrs of age, 30–50kg (New Life Pastures, Varysburg, NY) were used in these experiments. A previously optimized induction dose [36] of diazepam (0.5–1.5mg/kg) and ketamine (5–10mg/kg) mixture or teletamine (4mg/kg) and zolazepam (4mg/kg) mixture was introduced intravenously prior to surgery. During surgery, anesthesia was continued via an endotracheal tube using isoflurane with 100% oxygen and a tidal volume ventilator. The following intraoperative antibiotics were given: gentamicin 1.6mg/kg IM and penicillin G 6600U/kg IM. Analgesia was maintained by administration of buprenorphine (0.005–0.01mg/kg intravenously at the start of surgery and flunixin meglumine (2.2 mg/kg) intramuscularly during recovery. Post-operatively, the sheep also received flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg) IM once a day for two days and buprenorphine (0.005–0.01mg/kg) IM twice a day for one day. Anti-coagulative drugs, Aspirin (975mg/day), and Coumadin (20–30mg/day) as well as immune-suppressant Cyclosporine A (200mg/day) were given orally. These drug administrations were initiated 3 days before surgery and sustained until sacrifice.

Graft implantation was performed as previously described [36]. Briefly, heparin (100U/kg) was administered intravenously to the animals 30min prior to clamping of the left common carotid artery. Heparin was then infused intravenously at a rate of 100U/kg/hr throughout the surgery. After excising ≈ 5cm in-situ of native carotid in order to retain longitudinal tension, each A-TEV (4cm in length) was placed end to end in the carotid artery using interrupted suture technique. Following the unclamping of the artery and restoration of normal blood flow through the TEV, instruments were placed onto the newly sutured vessel allowing real-time monitoring of arterial dynamics during recovery as described recently[37]. A 4mm doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca NY) was placed proximal to the TEV, 1mm sonomicrometry crystals (Sonometrics Inc., London, Canada), were placed laterally opposite to each other at the midpoint of the A-TEV. An indwelling arterial pressure catheter (18ga intravenous catheter inserted 1cm and secured to outer vessel wall with polytetrafluoroethylene felt, attached to 0.040″ ID Tygon® tubing) was placed distal to the TEV in the native artery for invasive arterial pressure recording. This allowed for weekly evaluation of A-TEV hemodynamics during remodeling. All measurements of flow rates thus obtained were normalized to heart rate and reported as compared to contralateral native carotid.

Real time in-vivo monitoring of hemodynamics

At indicated time points, implanted probes were connected to corresponding transducers to enable data acquisition using Sonolab DS3 (Sonolab version 1.0.0.60, Sonometrics Inc., London, Canada) as previously described[37]. Following transducer calibration and establishment of stable connections, 30sec–1min of data were recorded. The recorded flow rates were then normalized to that of the native carotid on the contralateral side in order to remove fluctuations caused by non-sedated state of the animal. Dynamic radial compliance (percent) was calculated from the measurements of graft diameter and invasive arterial pressure using the following

rs = radius at systolic pressure

rd = radius at diastolic pressure

Ps = systolic pressure

Pd = diastolic pressure

Doppler ultrasound

Directional color doppler ultrasonography (Ultrasound-180 plus, Sonosite, WA) was performed bi-weekly to monitor graft patency. We obtained measurements of diameters and pulsatile flow velocity profiles of both carotids in order to ensure that bilateral carotid flow was maintained. Animals remained non-sedated but restrained for this procedure.

X-Ray imaging

At indicated times, immediately prior to euthanasia, X-ray images were acquired (Diamond 150th Unit, Eureka X-ray Tube Co., Litton, Chicago, IL) and developed with an automatic processor (Hope Micromax, Hope X-Ray Products, Warminster, PA). Both carotid arteries were cannulated proximal to the thoracic inlet using 3mm diameter tubing inserted approximately 4cm cranially. Contrast (5.25g, Iohexol, GE Healthcare Ireland, Cork, Ireland) was injected through both arteries simultaneously. Radiology settings of 77kV and 10mAs were utilized for an optimal exposure. This supplied an image of both the implanted A-TEV (left side) and control carotid (right side). Size calibration for measuring graft diameters was achieved by placing a 1.9cm metal bar on the outside of the film cassette.

Euthanasia and explantation of tissues

As previously described [36], animals were euthanized using pentobarbital sodium (5.85g, Fatal Plus, Vortech Pharmacueticals, Dearborn, MI). Immediately following sacrifice, both carotids were harvested and washed with heparinized saline. Instrumentation and connective collagenous tissue were removed before testing for vaso-reactivity, mechanical properties, and collagen and elastin protein content. The remaining tissue was preserved in 10% neutral buffered Formalin in order to perform histological analysis, SEM, and IHC.

Vascular reactivity

Ring sections of native carotids, explanted A-TEVs at 1-wk, 1-mo, and 3-mo, were subjected to a vasoreactivity test in order to evaluate SMC function, as optimized in our earlier work [36]. To this end, we employed a temperature controlled isolated tissue bath system containing Krebs-Ringer solution with constant oxygen supply (94% O2, 6% CO2). Tissue rings were mounted in the bath and attached to force transducers enabling measurement of contractile forces upon addition of vasoconstrictive agents, namely, (i) Endothelin-1 (ET-1, 10−8M) and (ii) U46619 (U4, 2×10−7M). The ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Y2, 1×10−6M) was added to each pre-constricted tissue to measure relaxation. Data was acquired using Powerlab unit and analyzed using Chart 5 software. All forces were normalized to the area of contact and reported in Pa.

Mechanical properties

Mechanical properties of explanted A-TEVs and native carotid arteries were assessed by measurement of Young’s moduli and Ultimate Tensile Strength, using an Instron tensile testing device (model 3343 with 50N load cell, Norwood, MA) as reported elsewhere[36]. The UTS and YM were calculated from the stress-strain profiles and reported in MPa.

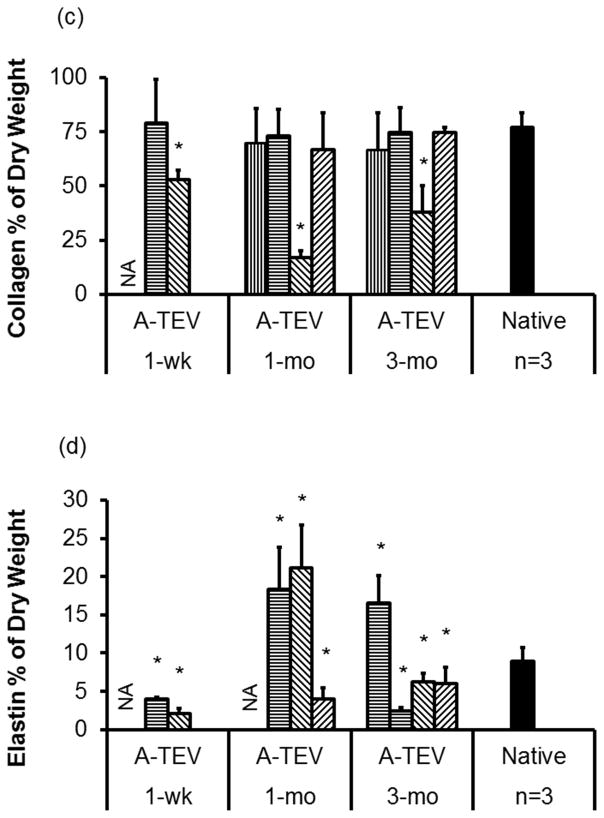

Collagen and Elastin quantification

Collagen quantification was based on a previously reported hydroxyl-proline assay [38, 39]. Tissues were lyophilized, and then hydrolyzed in 6N HCl overnight at 110°C. The following day, the hydrolysate was lyophilized again and resuspended in assay buffer (5% monohydrate citric acid, 12% trihydrate sodium acetate, 3.4% sodium hydroxide and 1.2% (v/v) glacial acetic acid, pH 6.5). Debris was removed by centrifugation and 100μL of supernatant was loaded into a 96 well plate followed by incubation with 50μL of chloramine-T (62mM, Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) for 20min at room temperature. Subsequently, 50μL of Ehrlich’s solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to each well and incubated at 65°C for 20min. OD (550nm) was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy 4, BioTek, Winooski, VT) and converted to hydroxylproline concentration using a standard curve (0–50μg/mL of L- hydroxyproline, Sigma). Hydroxyl-proline concentration was converted to collagen concentration using the conversion factor F. (F= 7.46g collagen per g hydroxyl-proline). Total collagen content, thus obtained is reported as a percent of dry tissue weight.

Elastin quantification was performed as previously reported [40, 41]. Tissues were lyophilized to measure dry weights, followed with protein dissolution in 0.1N NaOH for 1 hr at 95°C. Insoluble fraction containing cross-linked elastin was then hydrolyzed in 6N HCl at 100°C overnight. After hydrolyzed proteins were lyophilized, the residue was re-dissolved in a known volume of water. A protein standard was prepared using hydrolyzed elastin (Alpha elastin, EPC) at a concentration of 10μg/ml. The final reaction consisted of 100μL of ninhydrin reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) added to 1–10μg of samples which were loaded into 96-well plates and heated at 65°C for 1hr. The assay plates were placed into a microplate reader (Synergy 4, BioTek, Winooski, VT) and OD was read at 570 nm. Elastin amount was normalized as a percentage of dry tissue weight.

Histology and IHC

Explanted A-TEVs and native carotid arteries were cleaned using saline and pressure fixed in 10% Formalin. Samples were then dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol solutions, xylene substitutes and then embedded in paraffin as reported elsewhere. For histological evaluation, 5μm paraffin embedded tissue sections were stained with Harris Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, and Verhoeff’s elastin stains.

Tissue sections (5μm each) were deparaffinized, and subjected to pressure-activated high temperature antigen retrieval[17, 42]. Subsequently, the following antibodies were added in PBS containing 5% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) at 1 to 100 dilution: (i) Calponin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Dallas, TX), (ii) CD144 or VE-Cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), (iii) AIF (Allograft Inflammatory Factor) or anti-Iba-I (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA), (iv) e-NOS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and (v) CD163 (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). After overnight incubation at 4°C, corresponding secondary antibodies were used in 1:200 dilution for 1hr at room temperature. Cell nuclei were counterstained in blue (Hoechst 33342; 10mg/mL; 1:200 dilution; 5min at room temperature; EMD Millipore Laboratory Chemicals, Billerica, MA).

In order to quantify cell density, images were exported in indicated fluorescent color channels and opened in ImageJ software (NIH, USA, rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) and boxes of known area (150μm × 200μm) were interposed onto the original images to enable cell counting. Cell counting was done by hand and reported as cell#/mm2. To evaluate endothelial cell coverage in the lumen, cells appearing in the lumen were counted per field of view encompassing greater than 70% of lumen and reported as cell number per 100μm of lumen length.

RESULTS

Heparin and VEGF immobilization

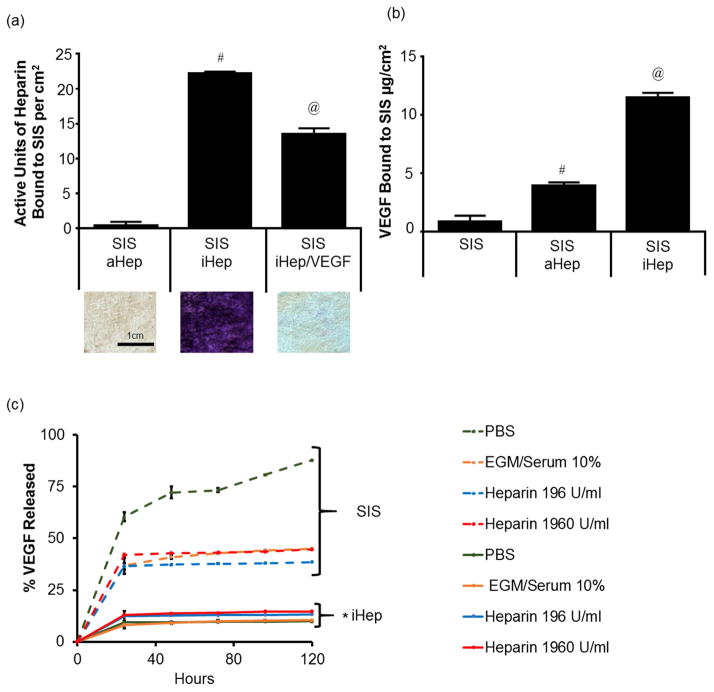

First, we immobilized heparin onto SIS using EDC/NHS crosslinking chemistry. Incubation of SIS with heparin (8000U/mL, pH 7.4) did not result in a significant amount of absorbed heparin (aHep) as measured by the toluidine blue assay (0.10±0.39 U/cm2). However, in the presence of EDC and NHS, a significant amount of heparin was covalently immobilized (iHep) to the SIS surface (22.20±0.28 U/cm2). Incubation of iHep SIS with recombinant VEGF protein (0.33 mg/mL) decreased the amount of detectable heparin significantly (13.55±0.95 U/cm2) (Fig. 2a), indicating binding of VEGF to heparin. Indeed, the surface concentration of VEGF as measured by standard ELISA was 11.48±0.41μg/cm2, which was significantly higher as compared to SIS without heparin (0.84±0.5 μg/cm2) or aHep SIS (3.94±0.26 μg/cm2), demonstrating that covalent immobilization of heparin on SIS was necessary for efficient immobilization of VEGF (Fig. 2b). Representative images (2mm × 2mm) are shown to demonstrate binding of toluidine dye to heparin on SIS surfaces (Fig 2a).

Figure 2. Immobilization of heparin and VEGF on SIS.

(a) Binding of heparin on SIS. iHep: covalently bound heparin using EDC/NHS chemistry; aHep: absorbed or physisorbed heparin. Representative bright field images of SIS are shown for each condition with bound toluene blue dye. Size of SIS is 2mm × 2mm. (b) VEGF immobilization on SIS as measured by direct ELISA. (a, b) The symbols (# and @) denote statistical significance as compared to the other two conditions. (c) VEGF release from SIS over time. Elution of VEGF from unmodified SIS or SIS with iHep in PBS with the indicated heparin concentrations or EGM medium containing serum. At the indicated times, the VEGF that was released in solution was measured by ELISA. The symbol (*) denotes statistical significance of all iHep from all SIS only samples.

To examine whether VEGF remained bound to SIS long-term, SIS alone or SIS with iHep were incubated with VEGF (0.33 mg/mL) for 4 hr. The unbound VEGF was washed and elution was monitored over time in the presence of PBS containing various concentrations of heparin (0, 196 or 1,960 U/mL) or Endothelial Growth Media (EGM2) supplemented with 10% serum (Fig 2c). After 24 hr, iHep SIS (solid lines) retained the majority of VEGF, releasing approximately 14% regardless of the concentration of heparin in the buffer. SIS with no heparin treatment released significantly more VEGF, especially when incubated in PBS alone, with no heparin or serum (approximately 87.3±0.3% was released after 120hr).

Implantation into the arterial system of an ovine model and in-vivo monitoring

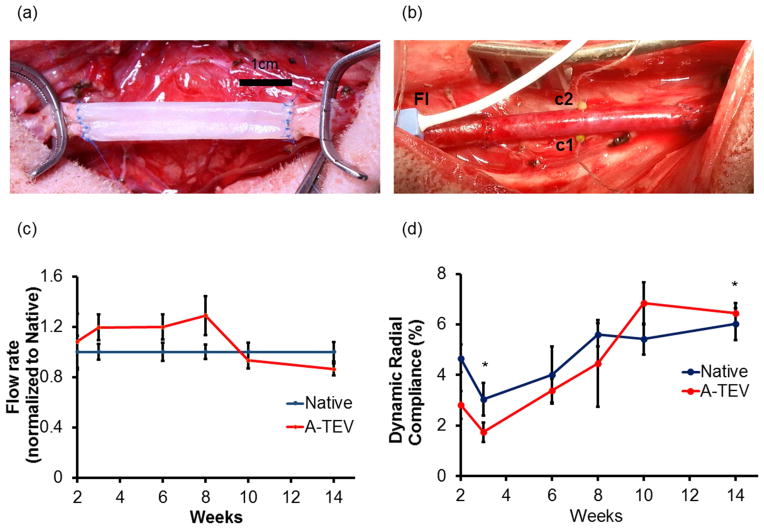

A-TEVs were implanted as interpositional grafts into the left common carotid artery of adult sheep using interrupted sutures (Fig 3a), as we reported previously[36]. A total of n=12 A-TEVs were evaluated at one week (1-wk, n=3), one month (1-mo, n=4) and three months (3-mo, n=4) post-implantation. One A-TEV occluded for unknown reasons yielding an overall patency rate of ~92%. Heparin only grafts (iHep SIS without VEGF) were implanted into n=2 animals, which occluded within 2 days.

Figure 3. A-TEV implantation.

(a) A-TEV sutured into native carotid vasculature using interrupted sutures. (b) A-TEV after arterial flow is re-established. Fl – Flow probe placed proximal to A-TEV to measure total blood flow through A-TEV; c1 and c2 – 1mm sonomicrometry crystals used to measure diameter changes. (c) Blood flow through A-TEV after implantation over the course of 3 months. Blood flow was normalized tonative control. (d) Dynamic radial compliance of A-TEV and native carotid measured over the course of 3 months. The symbol (*) denotes statistical significance between the indicated time points.

In order to monitor the condition of the grafts after implantation, A-TEVs (n=3) were instrumented with flow probes (Fig 3b, Fl), and sonomicrometry crystals (Fig 3b, c1&c2), which enabled digital monitoring of arterial flow rate and graft diameter over the course of 3 months. Mean arterial blood flow was recorded for at least 30 sec at each time point and normalized to the flow in native artery control. Over the course of 3 months we found that blood flow of A-TEV (208.8±46.3 to 273.7±13.0 mL/min) remained relatively constant compared to that of native control (200.9±25.8 to 291.8 ±22.7 mL/min) (Fig 3c), suggesting the A-TEV remained patent for the duration of the study with no obstruction to blood flow. Diameter change was recorded for at least 30 sec at each indicated time point. Over the course of 3 months, A-TEV radial dynamic compliance trended to increase and by week 10 it reached similar levels as native control (Fig 3d).

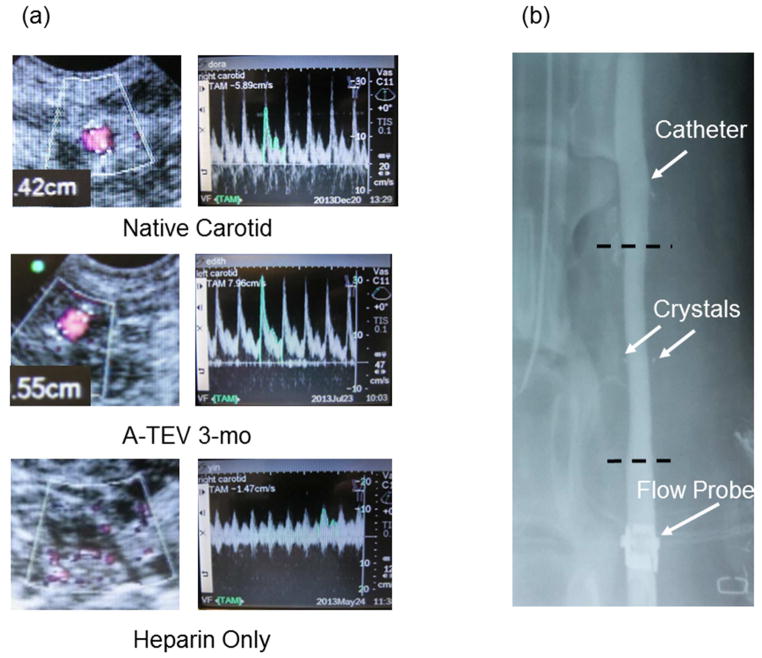

Evaluation of Graft Patency by Ultrasonography, X-Ray and Gross Analysis

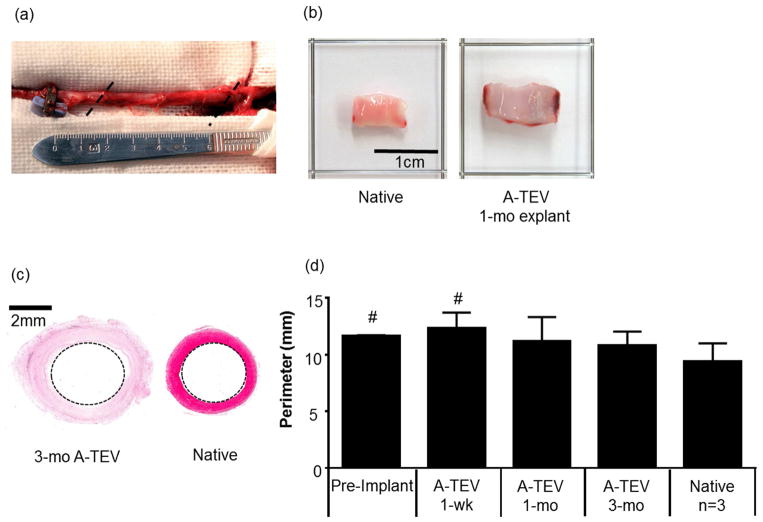

Patency of implanted A-TEVs was examined bi-weekly using directional color Doppler ultrasound. Implanted A-TEVs and native carotids displayed similar characteristic Doppler spectral traces indicating uniform pulsatile flow profiles (Fig. 4a). X-Ray imaging was done immediately before animal sacrifice demonstrating unobstructed flow and no stenosis or dilation at 1-wk, 1-mo or 3-mo post implantation (Fig 4b). Explanted A-TEVs were fully integrated into the host and nearly indistinguishable from surrounding tissue (Fig 5a). Most notably, the lumens of explanted A-TEVs were clean, with no sign of thrombus formation, similar to native controls. A representative picture of a 1-mo explant is shown in Fig 5b.

Figure 4. A-TEV imaging.

(a) Both native carotid and 3-Month A-TEV exhibit similar pulsewave pattern and diameter. Heparin only grafts occluded after 2–3 days. (b) X-Ray imaging demonstrates surgical instrumentation on A-TEV and integration after 1-mo. Flow probe, catheter and crystals are denoted using arrows. Anastomosis sites are represented using dotted lines.

Figure 5. Gross morphology of explanted grafts.

(a) Explanted graft at 3-mo post-implantation. Anastomosis sites are denoted with dotted lines. (b) Gross image of a representative 1-mo explanted A-TEV exhibits a clear patent lumen, similar to native tissue. (c) Representative histological image of a cross section from the middle of a 3-mo explant and a native artery. (d) Perimeter (mm) of pre-implanted A-TEVs (n=3), explanted grafts at the indicated times (n=3 at 1-week, n=4 at 1- & 3- months) and native arteries (n=3). The symbol (#) denotes statistical significance (p<0.05) as compared to native arteries.

In addition, the perimeter at the midsection of each explant was measured from histological images (H&E) using the Aperio ImageScope software V11.2 (Fig. 5c). The pre-implant (n=3) and 1-wk explants (n=3) were significantly larger (p<0.05) than native tissue (Fig. 5d). However, at 1-mo and 3-mo the perimeters of all A-TEV explants were similar to native controls demonstrating absence of dilation and remodeling toward native carotid perimeter.

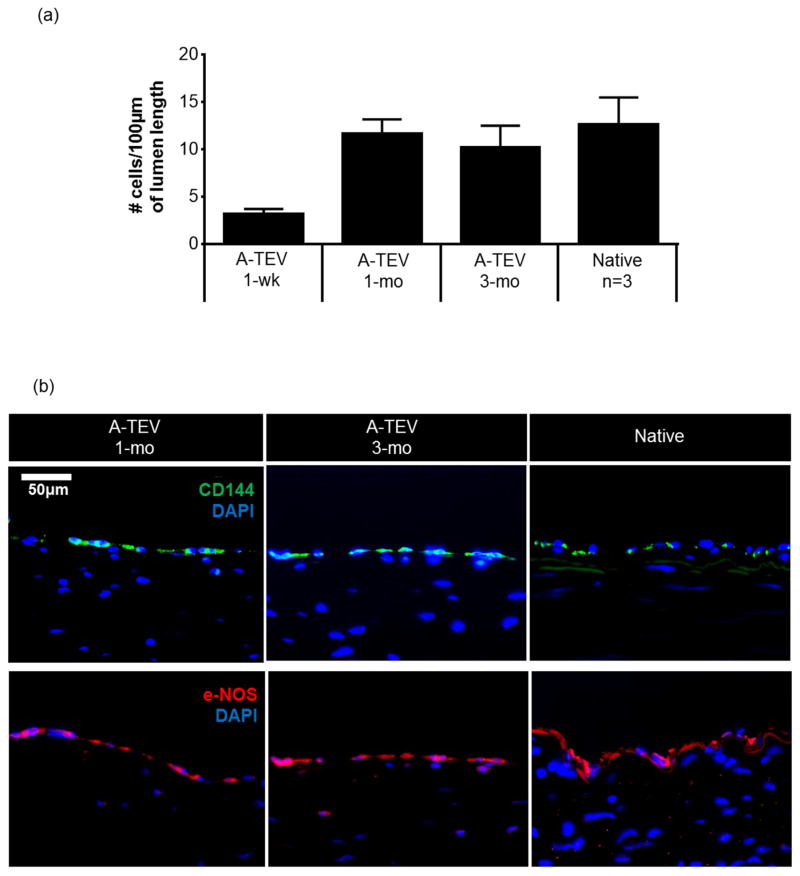

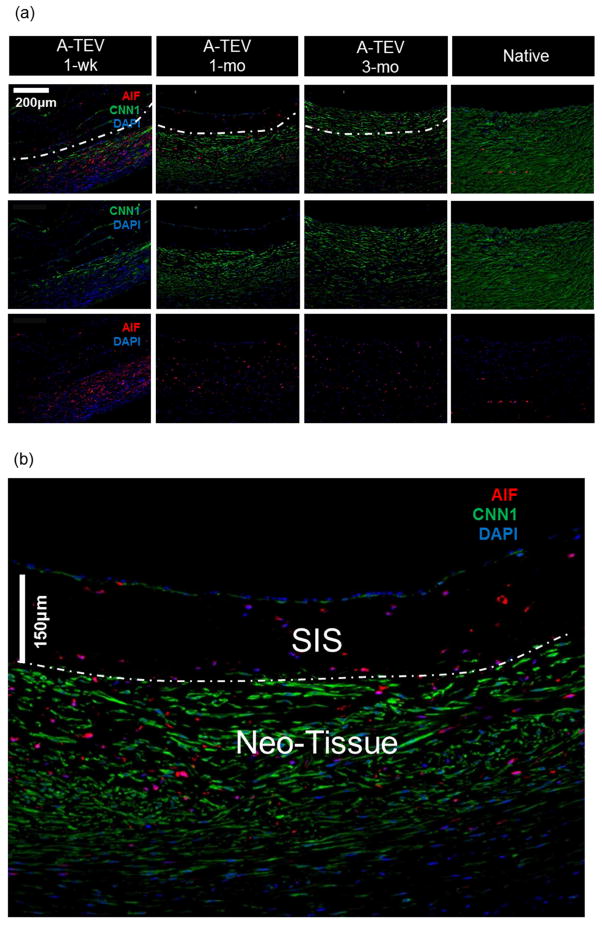

A-TEV developed a confluent endothelium within one month post-implantation

Tissue sections from the midsection of each graft were stained (H&E) and cells in the lumen of each graft were counted, and reported as number of cells per 100μm of lumen length (Fig. 6a). One-week explants demonstrated significantly lower number of cells (3.2 ± 0.5 per 100μm) compared to native (12.6 ± 2.8 per 100μm). However, this difference was resolved at 1-mo as cell coverage in the A-TEV lumen approached that of native artery.

Figure 6. Endothelialization of A-TEV grafts.

(a) Number of cells on the graft lumen. All counts were done from midsection of each graft and compared to native arteries (n=3). The symbol (*) denotes statistical significance (p<0.05) as compared to native arteries. (b) Immunostaining for endothelial markers CD144 and e-NOS from tissue sections isolated from midsection of 1-mo and 3-mo explanted A-TEVs. Explants were compared to native artery. Bar = 50 μm. (c) Enface SEM images of SIS, explanted tissues and native artery were taken at two different magnifications. Dotted squares illustrate the sections of the low magnification samples (500X, left) shown at higher magnification (2000X, right). At 1-wk the lumen exhibits adhesion and spreading of cells, which develop into a confluent monolayer by 1-mo. At 3-mo a confluent endothelium aligned in the direction of blood flow.

To evaluate the endothelium, midsections from 1-wk (not shown), 1-mo and 3-mo A-TEV explants were fixed, sectioned, and stained for CD144 and e-NOS (Fig. 6b). Native arteries served as a positive control. All explants at 1-mo stained positive for CD144 that was localized at cell-cell junctions. Cells along the lumen also stained positive for phosphorylated eNOS, suggesting a functioning endothelium [43]. At 1-wk, cells at the lumen did not stain for any of these endothelial markers.

Furthermore, SEM analysis of 1-wk, 1-mo, and 3-mo A-TEV explants showed development of an endothelial monolayer within one month post-implantation. Pre-implanted SIS and native arteries served as negative and positive controls, respectively (Fig. 6c). Pre-implant SIS samples exhibited no pores and a relatively smooth surface. At 1-wk, explants contained bound cells that were also spreading but the surface coverage was not uniform. At 1-mo a full cell monolayer was observed and at 3-mo endothelial cells were aligned in the direction of blood flow.

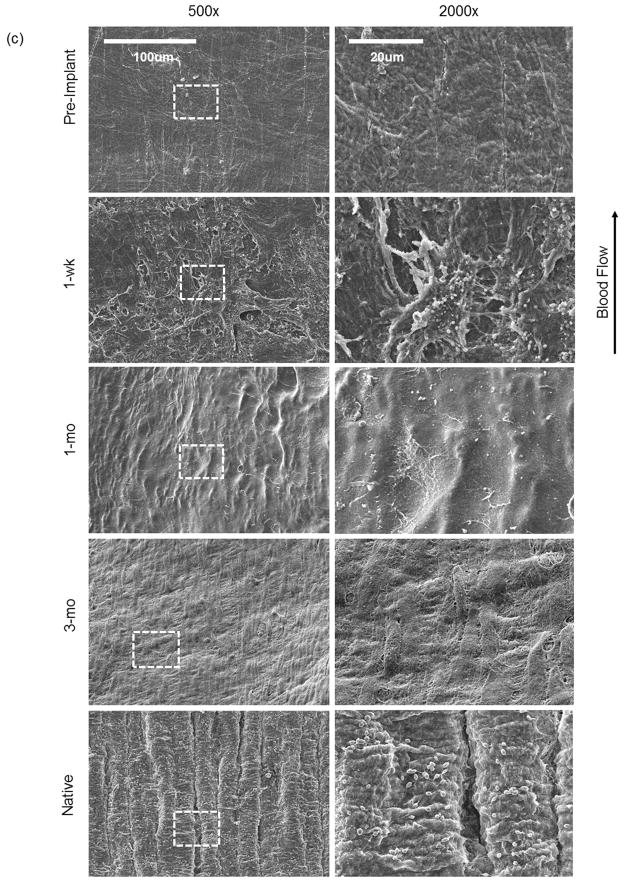

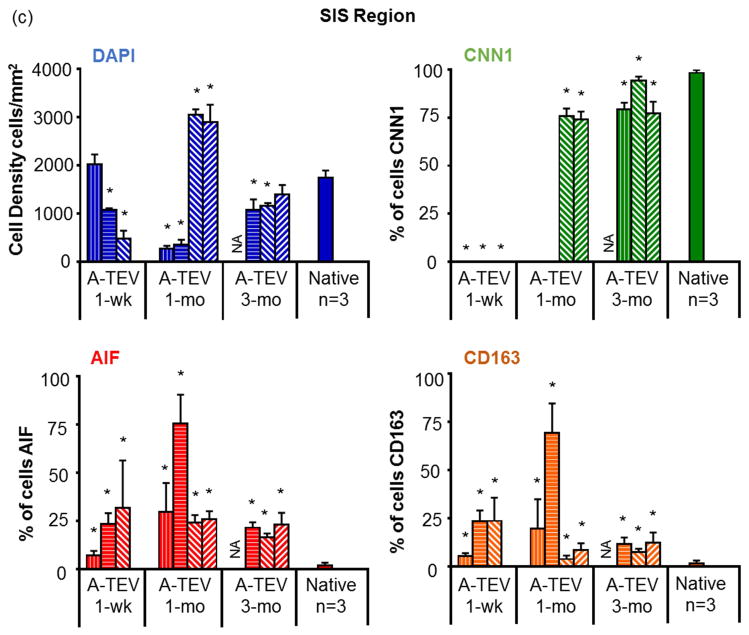

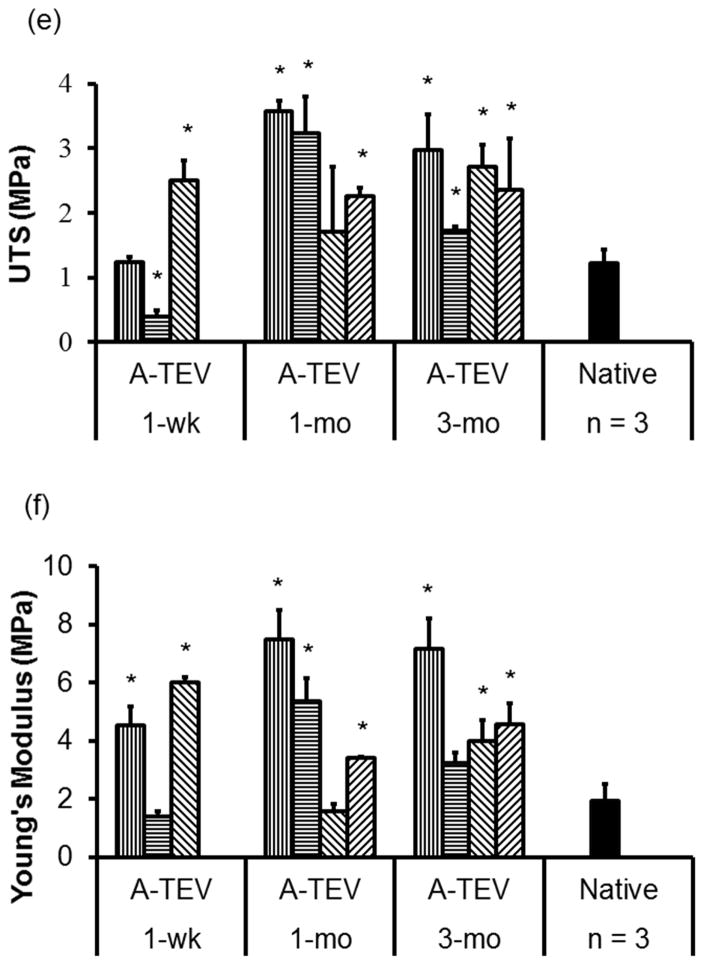

Medial layer development is rapid and stabilizes after 3 months

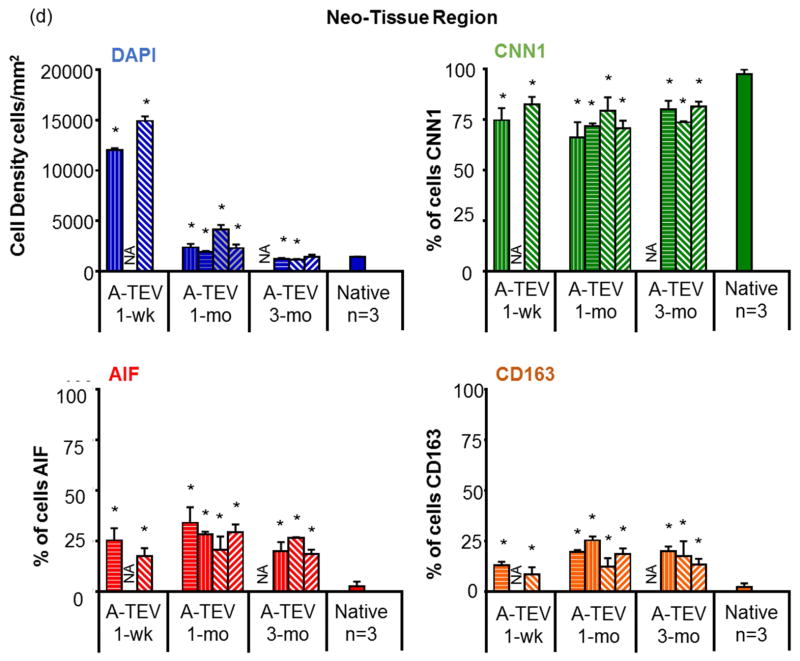

Next we evaluated cell influx in the medial layer of the A-TEV by immunostaining for the SMC marker protein Calponin-1 (CNN1), as well as macrophage markers, AIF and CD163 (Fig. 7a). Cell counts are shown for individual animals except for one 3-mo A-TEV that was not considered for staining due to compromised cell viability at the time of explant removal. At 1-wk, a significant number of host cells (477±164 to 2016±208 per mm2) migrated successfully into the SIS matrix (a region of approximately 150μm below the lumen, as indicated by the dotted line) (Fig. 7b). At 1-mo, two animals exhibited high influx of host cells into the SIS matrix (2,891 ± 367 & 3,055 ± 107 per mm2), while the other two showed only modest cell infiltration (266 ± 61 & 355 ± 96 per mm2). However, after 3-mo all A-TEVs exhibited similar cell infiltration (1,078 ± 214 to 1,394 ± 195 per mm2) and cell density approached that of native arteries (1,740±151 per mm2).

Figure 7. A-TEV vascular wall development.

(a) Immunostaining of explants for AIF, CNN1 and DAPI. SIS and Neo-Tissue region for 1-wk, 1-mo and 3-mo explants are defined by the white dotted line. (b) Enlarged image of a 1-mo A-TEV exhibiting low influx of cells in the SIS region. Most cells in SIS stained positive for AIF, while the majority of cells in the Neo-Tissue region stained positive for CNN1. (c, d) Total cell density and percentage of cells staining positive for CNN1, AIF or CD163 as measured for the SIS region (c) and Neo-Tissue region (d) of individual explants and native arteries. The symbol (*) indicates statistical significance compared to native arteries (n=3, p<0.05).

At 1-wk, a significant percentage of cells stained positive for AIF (6.9 ± 2.5% to 31.9 ± 21.5%), suggesting the presence of macrophages (Fig. 7c). The presence of AIF+ cells in the SIS matrix peaked at 1-mo (24±3.9% to 75.4±15.1%) and decreased at 3-mo (16.4±2.0% to 22.9±6.2%) albeit remained significantly higher than native tissue (1.7±1.5%, n=3, p<0.05). CNN1+ cells were not observed in the 1-wk and in two of the 1-mo explants but were present in the other two 1-mo explants (74.1±4.1% – 75.9±3.9%). The percentage CNN1+ cells increased at 3-mo (77.1±6.2% – 94.4±2.6%) approaching the levels of native tissue (98.3±1.5%).

All explanted A-TEVs exhibited a large number of cells surrounding the SIS matrix, in a region that we termed the neo-tissue (except for one 1-wk explant that lacked neo-tissue due to overt dissection) (Fig. 7d). At 1-wk, there were a large number of cells in the neo-tissue region (12,010 ± 204 to 14,921 ± 452 per mm2) but cell density decreased after 1-mo (1,933 ± 88 to 4,133 ± 463 per mm2) and 3-mo (1,158 ± 57 to 1,419 ± 221 per mm2), approaching the average cell density of native arteries (1,423 ± 41 per mm2). The vast majority of the cells in the neo-tissue region stained positive for CNN1 even at 1-wk (74.7±6.0 to 82.4±3.8%) and remained relatively unchanged up to 3-mo, indicating early recruitment of cells with smooth muscle phenotype. On the other hand, the percentage of AIF+ cells remained significantly higher than native arteries (2.50±2.34%, n=3, p<0.05) at all time points. A significant fraction of AIF+ cells also stained positive for CD163 (Fig. 7d, Fig. S1), indicating M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages, which are thought to contribute to constructive tissue remodeling [44, 45].

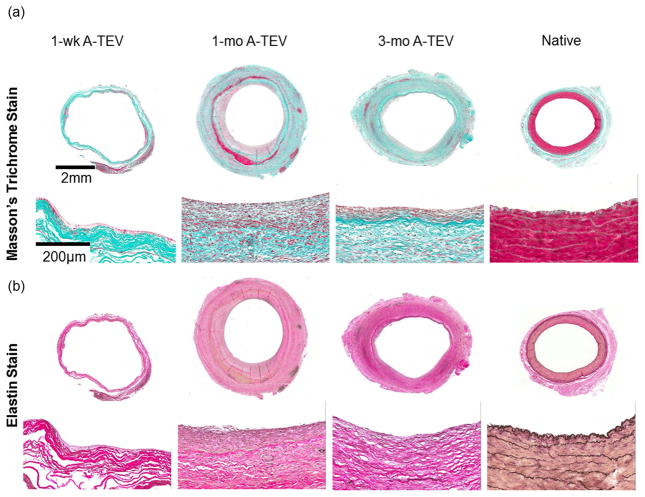

A-TEVs exhibit robust extracellular matrix synthesis and artery like mechanical strength

Collagen content was evaluated by Masson’s Trichrome staining (Fig. 8a) and quantified using the hydroxyproline assay and reported as percentage of dry tissue weight in order to remove any undesirable discrepancies due to the presence of connective tissue (Fig. 8c). With the exception of one 1-wk (52.9±4.4%), one 1-mo (17.1±3.0%) and one 3-mo explant (37.9±12.3%), the collagen content of all other explants was very similar to that of native arteries (76.9±6.7% of dry weight).

Figure 8. Extracellular matrix synthesis and mechanical properties of A-TEV explants.

(a, b) Masson’s Trichrome (a) and Verhoeff’s elastin staining (b) of 1-wk, 1-mo and 3-mo A-TEV explants and native arteries. (c, d) Quantification of collagen (c) and elastin (d) content as a percentage of dry weight for individual A-TEV explants. The symbol (*) indicates statistical significance compared to native arteries (n=3, p<0.05). (e, f) Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) (e) and Young’s Modulus (f) for each A-TEV explants and native arteries. Each bar represents explants from individual animals. The symbol (*) indicates statistical significance compared to native arteries (n=3, p<0.05).

Elastin was evaluated by Verhoeff’s elastin stain (Fig. 8b) and measured quantitatively using the Ninhydrin assay and reported as percentage of dry tissue weight (Fig. 8d). At 1-wk A-TEV explants contained significantly lower amounts of elastin (2.2±0.6% to 4.0±0.3%) compared to native arteries (8.9±1.8%, n=3, p<0.05). The elastin content increased in 1-mo (4.0±1.4% to 21.1±5.6%) and 3-mo (4.0±1.4% to 21.1±5.6%) but varied between explants with some exhibiting lower but some higher content than native arteries (8.9±1.8%). However, there was no evidence of fibrillar elastin, suggesting incomplete tissue remodeling by 3-mo post-implantation.

Interestingly, A-TEV explants exhibited remarkable mechanical properties pre-implant (UTS=4.67± 0.98 MPa and YM=24.14 ± 1.17 MPa). With the exception of one 1-wk explant, all others showed similar or higher Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) than native arteries. Similarly, other than one 1-wk and one 1-mo explant, all others showed similar or higher Young’s Modulus (YM) than native arteries (Fig. 8e, f).

A-TEVs exhibit vascular contractility and relaxation as early as one month post-implantation

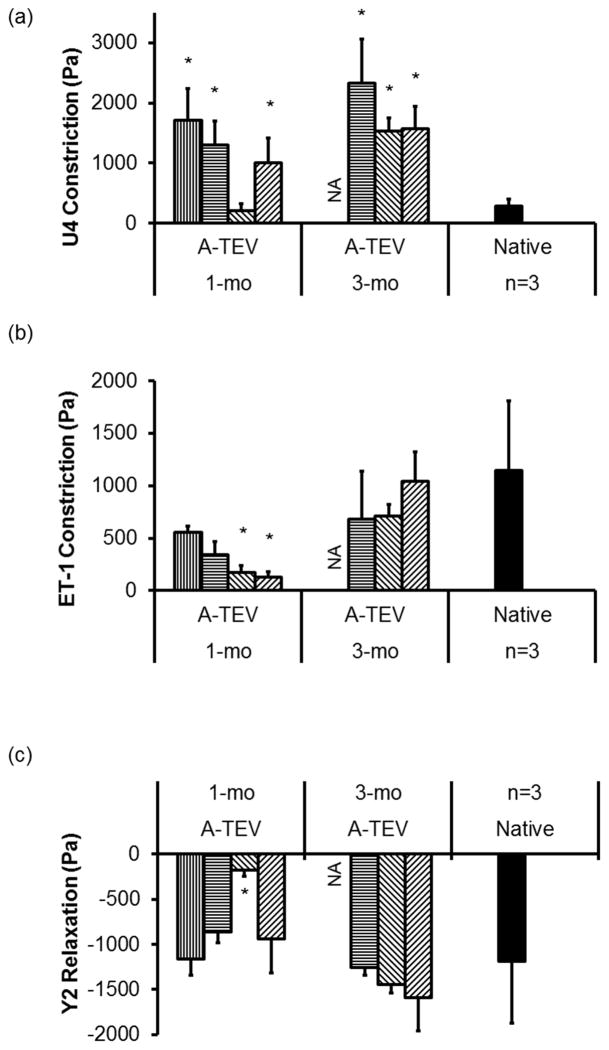

To evaluate the contractile function of A-TEV explants we measured vascular constriction and relaxation in response to vasoactive agonists (one 3-mo explant was not used for analysis). Although 1-wk A-TEV explants showed no vascular function, at 1-mo, all A-TEVs constricted in response to the thromboxane mimetic, U46619 and Endothelin-1 and dilated in response to the ROCK inhibitor, Y27632 (Fig. 9a). Interestingly, with the exception of one explant, all others exhibited higher vasoconstriction in response to U46619 when compared to native controls. Two out of four 1-mo explants demonstrated significantly less constriction in response to Endothelin-1 (ET-1), however at 3-mo all explants exhibited similar levels of vasoconstriction as native arteries (Fig. 9b). Finally, with the exception of one 1-mo explant, all others exhibited similar response to Y27632 as native arteries (Fig. 9c).

Figure 9. A-TEV explants exhibit contractile function.

Vascular reactivity of 1-mo and 3-mo A-TEV explants and native arteries in response to U46619 (U4), Endotheliin-1 (ET-1) or Y27632 (Y2). Each bar represents explants from individual animals. The symbol (*) indicates statistical significance compared to native arteries (n=3, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

We developed a cell-free off-the-shelf vascular graft capable of implantation into the arterial circulation of a large animal model. The A-TEV demonstrated host cell integration with development of a confluent endothelium in the lumen and a functional medial layer. Previous studies demonstrated that treatment with growth factors was beneficial for graft patency and perhaps also remodeling. In one study, poly(L-lactic acid)/polycaprolactone based vascular grafts that were treated with stromal cell derived factor (SDF-1α) were implanted successfully in rats. After implantation, SDF-1α enabled recruitment of Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPC) to the luminal surface of the graft and improved long-term patency when compared to untreated grafts[46]. Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factors (BDNF) has also been shown to capture EPCs under flow and enhanced endothelialization of decellularized arteries in rats [24]. Furthermore, heparin-coated, fast-degrading elastomers have also been evaluated in rats and shown to be effective as acellular grafts [23]. However, it is not clear that the results of these studies can be readily translated into more clinically relevant animal models [47].

Indeed, when similar acellular grafts were evaluated in large animal models, the success rates were less impressive. One study evaluated fibronectin and SDF-1α coated polyester based grafts by implanting them in the carotid arteries of sheep. While SDF-1α reduced thrombosis, less than 50% of the luminal surface of the grafts was covered by endothelium even after 3 months post-implantation. Endothelial coverage occurred near the anastomotic sites but not in the middle of the grafts, where thrombotic material accumulated [48]. Other studies developed cell-based vascular grafts that were decellularized before implantation [20, 21, 49]. These grafts were shown to be effective in large animal models or even clinical settings, however, host cell infiltration was limited near the anastomotic sites and as a result remodeling was also limited to those sites as well [19]. As a result, a functional endothelium may still be required to maintain patency [14, 22]. In addition, several weeks or months of preparation are required before these grafts are ready for implantation with potentially high associated costs.

Decellularized animal tissues have also been under investigation as they maintain tissue geometry as well as the native 3D architecture of extracellular matrix molecules, e.g. type 1 collagen and elastin [50], which might be helpful in guiding tissue remodeling and regeneration in vivo. In particular, SIS has been shown to guide tissue regeneration and at the same time provide strong protection against bacterial infection [51]. SIS has also been successfully used as replacement of large diameter (10mm) vessels, such as the infrarenal aorta of dogs [52]. Although the grafts remained patent, there was no indication of a healthy endothelium even months after implantation [30]. When SIS was used as a small diameter graft (4.3 mm) the success rate fell to 75% patency, possibly due to lack of endothelialization [30]. Furthermore, SIS grafts (10cm in length and 6mm in diameter) containing bound heparin were also evaluated in sheep with mixed results. All groups exhibited impaired patency rates with complications ranging from graft dilation, aneurysm formation, and anastomotic stenosis. Overall, the patency rate was reported to be 30% after 3–4 months [31]. A possible explanation for impaired patency rates might be attributed to slow rate of graft endothelialization from the anastomotic sites in sheep, similar to humans [53, 54].

To overcome these limitations our laboratory employed immobilized VEGF and microfluidic technology to capture EC under flow [33]. When immobilized on surface-bound heparin, VEGF enabled highly selective capture of EC under low and high shear stress, even from complex biological fluids such as blood. This finding suggested that VEGF might be effective in endothelializing vascular grafts after implantation in vivo. Indeed, herein we demonstrated that VEGF that was immobilized in the lumen of SIS conduits enabled graft endothelialization and maintained patency for the duration of the experiments (3 mo). Midsections of 1-mo and 3-mo explanted A-TEVs demonstrated a fully confluent luminal monolayer, which stained positive for endothelial markers CD144 and eNOS, indicating a mature and functional endothelium. Although the mechanism is not known, immobilized VEGF might have captured a population of cells from the blood, most likely those expressing one or both VEGF receptors (VEGF-R1 or VEGF-R2), as receptor-ligand binding was found to be necessary for capture of EC under flow in vitro [33]. These cells may have been endothelial progenitors that were capable of developing into a mature and functioning endothelium over time. However, at this time we cannot exclude the possibility that the initially captured cells might have facilitated subsequent endothelialization of the lumen through paracrine signaling.

While the rate of remodeling has been shown to vary early on (two out of four 1-mo A-TEVs demonstrated low host cell infiltration of SIS), after 3 mo all A-TEVs appeared to have similar cell density to native arteries. Furthermore, all 1-mo and 3-mo explants were shown to be functional and positive for CNN1, indicating development of mature vascular media. No bursting, aneurysms, or occlusions were observed during our study and A-TEVs remodeled to similar perimeters as native tissues after 1-mo in-vivo. Explanted A-TEVs also exhibited a high percentage of CD163+ cells peaking at 1-mo, suggesting a heightened presence of anti-inflammatory macrophages. Lastly, after 3-mo in vivo the vascular media contained high amounts of collagen and elastin that was accompanied by high mechanical strength and elastic modulus, which for many explants exceeded those of native arteries. However, fibrillar organization of elastin and mature smooth muscle fibers (trichrome staining) were absent in A-TEVs even at 3 months, suggesting that remodeling was not complete at that time.

In summary, we demonstrated that SIS-based cell-free TEVs with immobilized heparin bound VEGF, can be implanted successfully into the arterial vascular system of a clinically relevant large animal model and develop functioning endothelial and medial layers. These data are in agreement with a recent report from our laboratory, which found that the presence of donor mesenchymal stem cell derived SMCs in the vascular wall was helpful but not necessary for host cellular infiltration, smooth muscle maturation and development of contractile function after 3-mo in vivo [36]. Here we also demonstrated that when VEGF was immobilized on the luminal surface, donor ECs were also dispensable, thereby enabling generation of vascular grafts with “off-the-shelf” potential. This is a significant advancement in the field of vascular tissue engineering. Future directions may include refinement of growth factor immobilization, assessment of A-TEVs in disease models, and potentially clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Representative immunostaining of AIF and CD163 staining. White dotted circle illustrates co-localization of AIF and CD163 while white dotted rectangle illustrates only AIF staining. All CD163+ cells were also AIF+.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart and Lung Institute (R01 HL086582) to S.T.A. and D.D.S.

We thank Annette Featherstone and Donna Carapetyan at the Histology Service Laboratory at SUNY Buffalo for their help with histology. We also thank John Nyquist, the medical illustrator at SUNY Buffalo medical school for his original illustration (Fig. 1) and its inclusion in this manuscript.

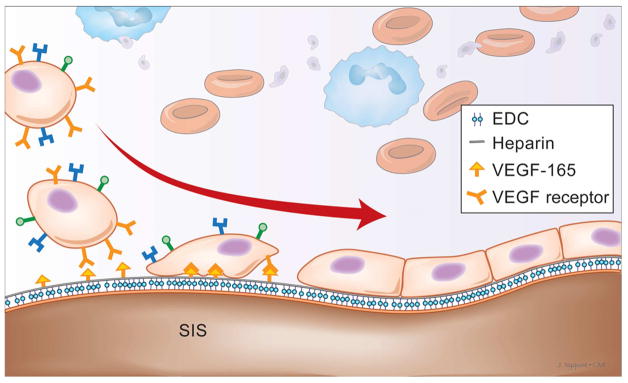

Figure 1.

Illustration of capture of cells on the SIS lumen decorated with heparin and heparin-bound VEGF.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2009 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifalian Alexander M, Tiwari A, Hamilton G, Salacinski Henryk J. Improving the Clinical Patency of Prosthetic Vascular and Coronary Bypass Grafts: The Role of Seeding and Tissue Engineering. Artificial Organs. 2002;26:307–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veith FJ, Moss CM, Sprayregen S, Montefusco C. Preoperative saphenous venography in arterial reconstructive surgery of the lower extremity. Surgery. 1979;85:253–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaudino M, Cellini C, Pragliola C, Trani C, Burzotta F, Schiavoni G, et al. Arterial versus venous bypass grafts in patients with in-stent restenosis. Circulation. 2005;112:I265–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achouh P, Boutekadjirt R, Toledano D, Hammoudi N, Pagny J-Y, Goube P, et al. Long-term (5- to 20-year) patency of the radial artery for coronary bypass grafting. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010;140:73–9. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vertrees A, Fox CJ, Quan RW, Cox MW, Adams ED, Gillespie DL. The use of prosthetic grafts in complex military vascular trauma: a limb salvage strategy for patients with severely limited autologous conduit. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2009;66:980–3. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819c59ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veith FJ, Gupta SK, Ascer E, White-Flores S, Samson RH, Scher LA, et al. Six-year prospective multicenter randomized comparison of autologous saphenous vein and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts in infrainguinal arterial reconstructions. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:104–14. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapsford RN, Oakley GD, Talbot S. Early and late patency of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene vascular grafts in aorta-coronary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981;81:860–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayers RD, Raptis S, Berce M, Miller JH. Long-term results of femorotibial bypass with vein or polytetrafluoroethylene. British Journal of Surgery. 1998;85:934–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biancari F, Railo M, Lundin J, Albäck A, Kantonen I, Lehtola A, et al. Redo Bypass Surgery to the Infrapopliteal Arteries for Critical Leg Ischaemia. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2001;21:137–42. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2000.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong Z, Niklason LE. Small-diameter human vessel wall engineered from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) The FASEB Journal. 2008;22:1635–48. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-087924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niklason LE, Gao J, Abbott WM, Hirschi KK, Houser S, Marini R, et al. Functional arteries grown in vitro. Science. 1999;284:489–93. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niklason LE. Replacement Arteries Made to Order. Science. 1999;286:1493–4. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quint C, Kondo Y, Manson RJ, Lawson JH, Dardik A, Niklason LE. Decellularized tissue-engineered blood vessel as an arterial conduit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9214–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019506108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.L’Heureux N, McAllister TN, de la Fuente LM. Tissue-Engineered Blood Vessel for Adult Arterial Revascularization. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1451–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.L’Heureux N, Dusserre N, Konig G, Victor B, Keire P, Wight TN, et al. Human tissue-engineered blood vessels for adult arterial revascularization. Nat Med. 2006;12:361–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swartz DD, Russell JA, Andreadis ST. Engineering of fibrin-based functional and implantable small-diameter blood vessels. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288:H1451–H60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaushal S, Amiel GE, Guleserian KJ, Shapira OM, Perry T, Sutherland FW, et al. Functional small-diameter neovessels created using endothelial progenitor cells expanded ex vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1035–40. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahl SLM, Kypson AP, Lawson JH, Blum JL, Strader JT, Li Y, et al. Readily Available Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3:68ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syedain ZH, Meier LA, Lahti MT, Johnson SL, Tranquillo RT. Implantation of Completely Biological Engineered Grafts Following Decellularization into the Sheep Femoral Artery. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2014;20:1726–34. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wystrychowski W, McAllister TN, Zagalski K, Dusserre N, Cierpka L, L’Heureux N. First human use of an allogeneic tissue-engineered vascular graft for hemodialysis access. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2014;60:1353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng H, Schlaich EM, Row S, Andreadis ST, Swartz DD. A novel ovine ex vivo arteriovenous shunt model to test vascular implantability. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;195:108–21. doi: 10.1159/000331415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W, Allen RA, Wang Y. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1148–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng W, Wen C, Wu Y, Li L, Zhou Z, Mi J, et al. The use of BDNF to enhance the patency rate of small-diameter tissue-engineered blood vessels through stem cell homing mechanisms. Biomaterials. 2012;33:473–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Animal models for vascular tissue-engineering. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2013;24:916–25. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang J, DeLillo N, Jr, Khan M, Nacinovich MR., Jr Review of small intestine submucosa extracellular matrix technology in multiple difficult-to-treat wound types. WOUNDS-A COMPENDIUM OF CLINICAL RESEARCH AND PRACTICE. 2013;25:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H-K, Godiwalla SY, Palmer B, Frimberger D, Yang Q, Madihally SV, et al. Understanding Roles of Porcine Small Intestinal Submucosa in Urinary Bladder Regeneration: Identification of Variable Regenerative Characteristics of Small Intestinal Submucosa. Tissue Engineering Part B, Reviews. 2014;20:73–83. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy F, Corbally MT. The novel use of small intestinal submucosal matrix for chest wall reconstruction following Ewing’s tumour resection. Pediatric surgery international. 2007;23:353–6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-1882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keckler SJ, Spilde TL, St Peter SD, Tsao K, Ostlie DJ. Treatment of Bronchopleural Fistula With Small Intestinal Mucosa and Fibrin Glue Sealant. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 84:1383–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lantz GC, Badylak SF, Coffey AC, Geddes LA, Blevins WE. Small intestinal submucosa as a small-diameter arterial graft in the dog. Investigative Surgery. 1990;3:217–27. doi: 10.3109/08941939009140351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavcnik D, Obermiller J, Uchida B, Alstine W, Edwards J, Landry G, et al. Angiographic Evaluation of Carotid Artery Grafting with Prefabricated Small-Diameter, Small-Intestinal Submucosa Grafts in Sheep. CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 2009;32:106–13. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prevel CD, Eppley BL, McCarty M, Jackson JR, Voytik SL, Hiles MC, et al. Experimental evaluation of small intestinal submucosa as a microvascular graft material. Microsurgery. 1994;15:586–91. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920150812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith RJ, Jr, Koobatian MT, Shahini A, Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Capture of endothelial cells under flow using immobilized vascular endothelial growth factor. Biomaterials. 2015;51:303–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith PK, Mallia AK, Hermanson GT. Colorimetric method for the assay of heparin content in immobilized heparin preparations. Analytical biochemistry. 1980;109:466–73. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fairbrother WJ, Champe MA, Christinger HW, Keyt BA, Starovasnik MA. Solution structure of the heparin-binding domain of vascular endothelial growth factor. Structure. 1998;6:637–48. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Row S, Peng H, Schlaich EM, Koenigsknecht C, Andreadis ST, Swartz DD. Arterial grafts exhibiting unprecedented cellular infiltration and remodeling in vivo: the role of cells in the vascular wall. Biomaterials. 2015;50:115–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koobatian MT, Koenigsknecht C, Row S, Andreadis S, Swartz D. Surgical technique for the implantation of tissue engineered vascular grafts and subsequent in vivo monitoring. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2015 doi: 10.3791/52354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stegemann H, Stalder K. Determination of hydroxyproline. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1967;18:267–73. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuman RE, Logan MA. THE DETERMINATION OF HYDROXYPROLINE. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1950;184:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long JL, Tranquillo RT. Elastic fiber production in cardiovascular tissue-equivalents. Matrix Biology. 2003;22:339–50. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starcher B. A Ninhydrin-Based Assay to Quantitate the Total Protein Content of Tissue Samples. Analytical Biochemistry. 2001;292:125–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geer DJ, Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Fibrin promotes migration in a three-dimensional in vitro model of wound regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:787–98. doi: 10.1089/10763270260424141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas SR, Chen K, Keaney JF. Hydrogen Peroxide Activates Endothelial Nitric-oxide Synthase through Coordinated Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation via a Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-dependent Signaling Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:6017–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown BN, Valentin JE, Stewart-Akers AM, McCabe GP, Badylak SF. Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown BN, Londono R, Tottey S, Zhang L, Kukla KA, Wolf MT, et al. Macrophage phenotype as a predictor of constructive remodeling following the implantation of biologically derived surgical mesh materials. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8:978–87. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Wang A, Tang Z, Henry J, Li-Ping Lee B, Zhu Y, et al. The effect of stromal cell-derived factor-1α/heparin coating of biodegradable vascular grafts on the recruitment of both endothelial and smooth muscle progenitor cells for accelerated regeneration. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8062–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Human P. Prosthetic vascular grafts: Wrong models, wrong questions and no healing. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5009–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Visscher G, Mesure L, Meuris B, Ivanova A, Flameng W. Improved endothelialization and reduced thrombosis by coating a synthetic vascular graft with fibronectin and stem cell homing factor SDF-1α. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8:1330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahl SL, Kypson AP, Lawson JH, Blum JL, Strader JT, Li Y, et al. Readily available tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:68ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schenke-Layland K, Vasilevski O, Opitz F, Konig K, Riemann I, Halbhuber KJ, et al. Impact of decellularization of xenogeneic tissue on extracellular matrix integrity for tissue engineering of heart valves. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shell DH, IV, Croce MA, Cagiannos C, Jernigan TW, Edwards N, Fabian TC. Comparison of small-intestinal submucosa and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene as a vascular conduit in the presence of gram-positive contamination. Annals of surgery. 2005;241:995. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000165186.79097.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Badylak SF, Lantz GC, Coffey A, Geddes LA. Small intestinal submucosa as a large diameter vascular graft in the dog. Journal of Surgical Research. 1989;47:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(89)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ueberrueck T, Tautenhahn J, Meyer L, Kaufmann O, Lippert H, Gastinger I, et al. Comparison of the ovine and porcine animal models for biocompatibility testing of vascular prostheses. Journal of Surgical Research. 2005;124:305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berger K, Sauvage LR, Rao AM, Wood SJ. Healing of arterial prostheses in man: its incompleteness. Annals of surgery. 1972;175:118. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197201000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Representative immunostaining of AIF and CD163 staining. White dotted circle illustrates co-localization of AIF and CD163 while white dotted rectangle illustrates only AIF staining. All CD163+ cells were also AIF+.