Abstract

The present investigation was designed to evaluate whether mothers’ emotion experience, autonomic reactivity, and negatively biased appraisals of their toddlers’ behavior and toddlers’ rates of misbehavior predicted overreactive discipline in a mediated fashion. Ninety-three community mother–toddler dyads were observed in a laboratory interaction, after which mothers’ emotion experience and appraisals of their toddler’s behavior were measured via a video-recall procedure. Autonomic physiology and overreactive discipline were measured during the interactions. Mothers’ negatively biased appraisals mediated the relation between emotion experience and overreactive discipline. Heart rate reactivity predicted discipline independent of this mediation. Toddler misbehavior appeared to be an entry point into the above process. Interventions that more actively target physiological and experiential components of mothers’ emotion may further reduce their overreactive discipline.

Harsh or overreactive discipline is a replicated correlate of early childhood conduct problems (e.g., Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1998; Denham et al., 2000; O’Leary, Slep, & Reid, 1999). Although definitions vary somewhat, the common core of such parenting includes behavior directed at the child that is excessively angry, irritated, and physically rough (D. S. Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993). A better understanding of why parents are overreactive should improve the ability to help parents in their efforts to alter the problematic trajectories of children with conduct problems (Kendziora & O’Leary, 1992) and could reveal new treatment targets. Understanding overreactive discipline in families of toddlers is of particular importance because early onset externalizing problems appear to be especially stable (Campbell, 1995; O’Leary et al., 1999) and because parents have considerable influence on the socialization of young children (Reid, 1993).

Effective discipline must be organized around the well-being of the child. However, the challenging nature of discipline-oriented interactions holds great potential for eliciting negatively valenced thoughts and emotions in parents, reactions that may interfere with optimal socialization practices. A growing body of research has shown that mothers’ negative emotional states and negatively toned child-related cognitions are associated with overreactive discipline (e.g., Lorber & Slep, 2005; Slep & O’Leary, 1998). The theoretical premise behind this work is that mothers’ responses to their children are influenced not only by what their children do but also by how mothers interpret and emotionally respond to their children. In this vein, the focus of the present investigation was on previously unstudied relations among self-report and autonomic indicators of mothers’ emotion, mothers’ negatively biased appraisals of their toddlers’ behavior, and toddlers’ actual rates of misbehavior in predicting overreactive discipline.

Emotion and Discipline

Mothers’ self-reported experience of negative emotion is associated with overreactive discipline (E. H. Arnold & O’Leary, 1995; Lorber & Slep, 2005; Smith & O’Leary, 1995). From a functionalist perspective, currently the dominant view in emotion theory (Consedine, Strongman, & Magai, 2003), emotions are thought to motivate behavior, preparing individuals for action (e.g., Izard, 1991; Levenson, 1994). Applying the functionalist perspective to parenting (e.g., Dix, 1991; Lorber & Slep, 2005), the misbehavior exhibited by children in discipline encounters elicits negative emotion in the parents because child misbehavior runs against parental goals (e.g., child compliance). High levels of negative emotion likely predispose parents to use emotionally congruent overreactive discipline to stop the unpleasant behavior.

In addition to emotion experience, increases in the activity of the autonomic nervous system might predict overreactive discipline. Measures such as heart rate (HR) and electrodermal activity (EDA) are thought to reflect emotion activation when measured in response to emotion-eliciting stimuli (see Lang, 1994). The influence of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system on HR via the vagus nerve (cardiac vagal tone) has received increasing attention as a measure of emotional responding as well (Beauchaine, 2001; Porges, 1995). Increases in HR and EDA and decreases in respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA)—an index of vagal tone—accompany negative emotional states (Beauchaine, 2001; Bongard, Pfeiffer, al’Absi, Hodapp, & Linnenkemper, 1997; Grossman & Svebak, 1987; Lacey, 1967; Lovallo et al., 1985; Porges, 1995). Furthermore, meta-analytic findings suggest that HR and EDA reactivity are positively associated with physical aggression (Lorber, 2004). Given the replicated association of negative emotion and overreactive discipline and the aggressive nature of overreactivity, these physiological responses may then be associated with overly harsh, emotionally charged reactions to child misbehavior. Although no data have yet demonstrated a relation between autonomic reactivity and overreactive discipline, two studies have found that child abusers exhibit greater autonomic reactivity to aversive child stimuli (Frodi & Lamb, 1980; Wolfe, Fairbank, Kelly, & Bradlyn, 1983), with one nonreplication (Friedrich, Tyler, & Clark, 1985).

Appraisals and Discipline

With respect to appraisals of toddler behavior, two separate groups of investigators have reported findings indicating that the more mothers rate their children as negative, in disagreement with objective observers, the more they are observed to practice (Lorber, O’Leary, & Kendziora, 2003) and self-report (Murray & Johnston, 2003) overreactive discipline. Such negatively biased appraisals are typically conceptualized as occurring early in a hypothetical chain of social information processing. The influential social information-processing model of Crick and Dodge (1994) was originally developed to understand children’s information-processing patterns in peer contexts but has also proven useful for understanding overreactive discipline (Lorber et al., 2003).

Crick and Dodge (1994) theorized that multiple stages of cognition mediate the relations between environmental events and behavior. Social information processing begins with the encoding stage, at which point information is received subject to attentional processes. Next, social cues are given meaning in the interpretation stage. Interpretation is followed by a period of goal clarification. The response access or construction stage, during which potential behavioral responses are accessed from memory or new responses are formed, occurs next. This stage is followed by response decision, when previously generated potential responses are weighed according to their likely outcomes and one is selected for enactment. In the final stage—behavioral enactment—the selected response is performed. Although the information-processing stages are typically represented in a linear fashion, the model allows for nonlinear processing, in which stages are skipped or information flows backward through some processing steps.

In the Crick and Dodge (1994) scheme, mothers’ biased appraisals would be conceptualized as occurring at the interpretation stage of social information processing (Lorber et al., 2003). As a result, they may have the potential to influence later aspects of social information processing such as response selection and enactment, where overreactive responses are presumably generated. In other words, negative appraisals may lead to negative parental behavior, such as overreactive discipline.

Emotion and Appraisals: Joint Prediction of Overreactive Discipline

It is unlikely that negative appraisal bias and emotion operate independently in their prediction of overreactive discipline. Existing research has suggested that measures of maternal emotion (e.g., mood, autonomic activity) are associated with social cognitive variables such as appraisals of and attributions for child behavior (Bugental et al., 1993; Dix, Reinhold, & Zambarano, 1990; Dix, Ruble, Grusec, & Nixon, 1986; Jouriles & Thompson, 1993; Slep & O’Leary, 1998; Smith & O’Leary, 1995; Weis & Lovejoy, 2002). An increasing role of emotion in theoretical models of social information processing is also evident (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994; Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000). Given the growing body of literature on social–cognitive and emotional correlates of discipline and studies that have indicated cognition–emotion relations, mediational hypotheses are suggested.

Negative emotion might have an effect on overreactive discipline by causing negatively biased appraisals. Correlational and experimental evidence suggests that negative maternal emotion is associated with negative appraisals of child behavior (Jouriles & Thompson, 1993; Weis & Lovejoy, 2002). These findings are consistent with the well-known research on emotion-congruent cognition outside of the family literature (e.g., Bower, 1981) and with experiments indicating that emotion has a causal impact on appraisals (e.g., Ciarrochi & Forgas, 2000). The activation of negative emotion in a mother likely primes her to perceive her toddler’s behavior in a manner that is congruent with the emotion, sometimes causing misinterpretations.

On the other hand, negatively biased appraisals may have their effect on overreactive discipline by causing negative emotion. Negative appraisals of child behavior are probably not benign events but events that elicit negative emotion. This state of negative emotion may, in turn, cause overreactive discipline. Mothers with more frequent negatively biased appraisals perceive more negative child events. Thus, these mothers have more opportunities for their negative emotions to become aroused than do other mothers. No experimental studies have demonstrated that appraisals of child behavior influence negative emotion in the parenting literature. However, experiments from outside the parenting literature have demonstrated that appraisals cause emotion experiences (e.g., Roseman & Evdokas, 2004). Moreover, in the parenting literature, Slep and O’Leary (1998) reported a marginally significant effect of child-centered attributions for child misbehavior on mothers’ self-reported anger. Furthermore, Bugental and her colleagues (1993) demonstrated that mothers’ perceptions of low parental power are associated with negative affect and increases in HR and EDA. These two studies suggest that other, potentially related aspects of mothers’ social information processing may be causally implicated in their emotional reactions to child stimuli.

In sum, the experimental literature does not clearly support the causal primacy of either cognition or emotion. Accordingly, the questions investigated in the present study were (a) whether negative appraisal bias mediates a negative emotion–overreactivity relation or (b) whether negative emotion mediates a negative appraisal bias–overreactivity relation. Our assessment of emotion included measures of autonomic reactivity in addition to self-report.

Child Effects

Experimental evidence (reviewed by Lytton, 1990) suggests that difficult child behaviors cause parents to behave more negatively toward children. Although these studies have not explained the mechanisms by which children influence their parents, the experimental manipulation of E. H. Arnold and O’Leary (1995) showed that exposure to negative child emotion (a prominent component in toddlers’ misbehavior) increases mothers’ experience of negative emotion and overreactive discipline. Through its effect on mothers’ emotion and emotions’ effect on mothers’ appraisals, child misbehavior may carry forward to influence overreactive discipline. Additionally, child misbehavior may directly influence a mother’s appraisals of her child by priming congruent perceptions of the child (Higgins, Bargh, & Lombardi, 1985). This effect may further carry forward through mothers’ emotional responses to affect discipline. Ultimately, through its influence on mothers’ cognition and emotion, child misbehavior may contribute to the coercive, escalating process characteristic of mother–child dyads in which the children exhibit clinically significant behavior problems (Snyder, Edwards, McGraw, Kilgore, & Holton, 1994). Accordingly, after evaluating mediated pathways among mothers’ emotion experience, autonomic reactivity, and negatively biased appraisals of their children’s behavior in predicting overreactive discipline, we modeled child misbehavior as a cause of these processes.

Method

Participants

A total of 97 mothers and their 2to 3-year-old toddlers, who had no diagnosed mental, sensory, or physical handicaps, were recruited for participation in return for a one-session parenting workshop. Participants were recruited through advertisements in community newspapers, flyers posted in the community, phone calls based on published birth records in a local newspaper, and a random-digit telephone-dialing procedure. Four dyads were excluded from all analyses because the children displayed such low rates of neutral or positive behavior in the interactions with their mothers that one of the study variables could not be meaningfully calculated (see the Results section, below). The remaining 93 dyads had toddlers (M child age in months = 31.76, SD = 6.04; 47 of them girls) with externalizing factor T scores between 32 and 80 (M = 55.06, SD = 9.22) on the Child Behavior Checklist for 1.5to 5-Year-Olds (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). Thirty-one (33.33%) of the toddlers had externalizing scores in the borderline and clinical ranges (T > 60). Mothers’ mean age was 35.00 years (SD = 4.58). They had a median annual family income of $90,000, ranging from $11,000 to $400,000. All mothers had at least a high school education, 15 of them had undergraduate degrees, and 6 had graduate or professional degrees. Twenty-nine of the toddlers were only children; the remainder had one (45), two (14), or more (5) siblings. Eighty-four of the mothers were married, with 6 separated or divorced and 3 never married. Eighty-eight mothers self-identified themselves as Caucasian, 3 as Hispanic/Latina, 1 as Asian, and 1 as Native American.

Procedure

Preinteraction

After providing informed consent, the mother completed questionnaires to assess child and maternal characteristics and demographic information. Once the mother had completed the questionnaires, electrodes were attached for physiological recording. The mother was then escorted alone to the interaction room. The interaction room contained an adult-size chair, a telephone, a string mobile that hung within reach of children, three low tables (within reach of children) with a variety of nontoy attractive items (e.g., typewriter, bell, colored pencils, clear jar of candy), a set of attractive toys on the floor next to an empty plastic container, a different set of toys (boring, age-inappropriate toys) in a crate out of view beneath the chair, and a string that ran across the floor, marking the interaction space. The mother was instructed to sit quietly for a few minutes, for the purpose of “measuring your body while you are resting,” while the experimenter was in an adjoining room. This 4-min period served as an adaptation phase prior to measuring resting physiology. Following the adaptation phase, the mother’s resting physiology was assessed for 5 min while she remained seated.1

Next, the experimenter administered instructions for the interaction. The mother was told that the interaction would consist of three tasks: clean up, phone, and quiet time. The three-task protocol is a well-established laboratory discipline-encounter protocol (e.g., E. H. Arnold & O’Leary, 1995; Slep & O’Leary, 1998) designed to elicit challenging but typical toddler behavior. For the clean-up task, the child was to clean up the attractive set of toys as quickly and independently as possible. For the 10-min phone task, the child was to play with the second set of boring toys quietly and independently while the mother remained seated and conversed with the experimenter on the phone, with the first set of toys now being off limits. For the 10-min quiet-time task, the child was expected to read a picture book quietly and independently while the mother worked on a questionnaire, with all toys being off limits. Other items that were off limits throughout the interaction were pointed out. These items—objects attractive to toddlers but not typically considered toys—were within easy reach of the child. Furthermore, the mother was told to keep her child from crossing a string that ran across the floor, so as to keep her child in the range of the camera. Because the validity of the phone task may have depended in part on the expectation that it would be followed by the quiet-time task, mothers were given instructions for the quiet-time task, despite the fact that the interaction was terminated at the end of the phone task.

Interaction

Following task instructions, the mother was then videotaped interacting with her child for up to 22 min (minimum = 12 min; M = 16.70, SD = 2.89), divided between the clean-up and phone tasks described above. Variability in the length of interaction was due to the speed with which the child put away toys in the clean-up task, ranging from 2 to 12 min; the phone task was always 10 min. Only data drawn from the phone task were analyzed in the present study, as maternal cognition and emotion experience were assessed for the phone task alone.

Video recall

Assessment of moment-to-moment variations in emotion experience cannot occur during the interaction without significantly disrupting it. Thus, video-recall procedures have been developed and validated (Gottman & Levenson, 1985; Lorber, 2005). After the interaction, the mother twice watched the videotape of the phone-task portion of her own interaction in a room separate from her child. She made continuous ratings of her child’s behavior (first) and her own emotion using a rating dial apparatus. Spanning 240°, the dial was divided into three regions, with negative denoted by a red region to the left of center (from 8 to 12 o’clock), positive marked by a green region to the right (from 12 to 4 o’clock), and neutral at 12 o’clock. The mother was instructed to use her own definitions of child negativity, positivity, and neutrality in rating child behavior. After rating her child’s behavior, the mother again watched the videotape of the phone task and made continuous ratings of her emotion as experienced during the interaction. A computer with custom dial-recording software acquired dial output in 5-s intervals. Each interval was classified as negative, neutral, or positive according to where the dial was positioned for the majority of the interval (i.e., more than 2.5 s)

Measures

Child behavior

Using the same dial apparatus described above, moment-to-moment child behavior during the 10-min phone task was coded as positive, negative, or neutral by two independent observers who were masked to the study hypotheses. Displays of negative affect (e.g., crying, whining, having tantrums, screaming), noncompliance with maternal commands, verbal and physical aggression toward the mother, destruction (e.g., throwing toys, kicking the wall), and task rule violations (e.g., touching forbidden objects, initiating communication with the mother) were coded as negative behavior. Behaviors coded as neutral included sitting quietly on the floor without playing and responding verbally to mother-initiated verbal communication. Behaviors coded as positive included playing with toys, displaying affection in response to mother initiated communication, and complying with maternal commands. A sample of 31 dyads was randomly selected for the assessment of intercoder agreement. Observers were unaware of which tapes would be sampled for reliability assessment. Mean agreement for classifying intervals as negative versus neutral/positive was 95% (agreement was always 88% or higher; Cohen’s kappas averaged .84, indicating acceptable intercoder agreement). A summary child misbehavior score was calculated by summing the number of intervals rated by the observer as negative.

Negative appraisal bias

Negative appraisal bias reflects mothers’ negative classification of observer-coded positive or neutral child behavior. To form the negative appraisal bias variable, comparisons of mothers’ and coders’ dial ratings of child behavior were made for each 5-s interval.2 Negative appraisal bias was computed as the probability that a mother evaluated observer-coded positive or neutral child behavior intervals as negative and thus could range from 0 to 1. For example, a score of 0 indicates that the mother never classified observer-coded positive or neutral behavior intervals as negative, whereas a score of .25 indicates that such a discrepancy occurred in one quarter of the observer-coded positive or neutral intervals.

Maternal emotion experience

After rating her child’s behavior, the mother again watched the videotape of the phone task and made continuous ratings of her emotion as experienced during the interaction from extremely positive to extremely negative using the video-mediated dial-rating procedure. The dial position was monitored and recorded by computer. For each successive 5-s interval, the number of seconds the dial was in the negative, neutral, and positive regions and the average position of the dial for the time it was in the negative and positive regions were recorded (following Smith & O’Leary, 1995; Lorber & Slep, 2005). Dial position is expressed on a scale from -100 to 100. Scores below zero correspond to the negative region of the dial, scores above zero correspond to the positive region, and zero corresponds to neutral. Affect scores for each interval were calculated by adding (a) the time the dial was in the positive region X average dial position during that time to (b) the time the dial was in the negative region X average dial position during that time. Thus, the index ranges from intensely positive emotion at the high end to intensely negative emotion at the low end. For each participant, the mean of these scores was used for analysis. Lower scores indicate more negative emotion.

Physiological reactivity

Cardiac and electrodermal responses were recorded with a Biolog ambulatory physiological monitor (UFI, Moro Bay, CA), a small unit worn like a purse. EDA was operationalized by skin conductance level, measured at sampling rate of 100 Hz by passing a small voltage between two contoured Ag-AgCl electrodes filled with BioGel (an isotonic NaCl electrolyte gel) attached with Velcro bands to the volar surfaces (second segment from the tip) of two adjacent fingers on each participant’s nondominant hand. Mean EDA, as well as HR, was calculated in 30-s intervals to match the structure of the RSA estimates; RSA estimates are known to have poor reliability when the measurement interval is very short (Berntson et al., 1997). Cardiac interbeat interval (IBI) data were collected to derive HR (HR = 60,000/IBI). Cardiac IBI is measured as the time interval between successive R-waves (i.e., corresponding to heartbeats) of the electrocardiogram (ECG). ECG was recorded at a sampling rate of 1 kHz using three Ag-AgCl disposable stress foam electrodes placed in a modified Lead II configuration (active electrodes on each mother’s lower left ribcage and right collar bone, reference electrode placed on the lower right ribcage). Cardiac RSA was also derived from the IBI data. RSA was assessed using Porges’s (1985) method of quantifying the variability in HR associated with vagal influences. Vagal influences on HR are observed in the high frequency range (e.g., Saul et al., 1991). Therefore, the variance of the band comprising 0.12 to 0.40 Hz served as the RSA variable for further analysis. Mean EDA, HR, and RSA were computed for two separate periods: (a) a 5-min resting baseline following a 4-min adaptation period that took place after the questionnaires had been completed (baseline physiology) and (b) during the phone task. Reactivity scores were computed for each physiological measure by subtracting mean baseline levels from mean phone-task levels.

Overreactive discipline

Global maternal overreactivity during the phone task was rated on a single 7-point scale that reflected the degree and frequency of anger or irritation exhibited by the mother, through vocal (e.g., yelling) or nonverbal (e.g., grabbing) channels, in response to child misbehavior. Higher scores indicate more overreactivity. Two research assistants, who were masked to the hypotheses and who coded only overreactivity, coded 100% of the interactions. Because the data were positively skewed, Finn’s r (an alternative to the intraclass correlation when data are skewed; see Whitehurst, 1984) was used to assess reliability; Finn’s r = .91, indicating acceptable interrater agreement. The two coders’ ratings were averaged for use in subsequent analyses.

Results

Missing Data Imputation and Descriptive Analyses

The primary sources of missing data (overall rate of 4.2%) were interaction HR and RSA (both based on uninterpretable ECG; N = 15) due primarily to electrodes being pulled off. The same problem occurred for one mother’s EDA data. Software failures resulted in lost dial data for emotion (N = 5) and child (N = 2) ratings. Multiple imputation using NORM (Schafer, 1999) was used to prevent data loss and to avoid biasing the data by limiting the sample to participants with complete data on all variables (Schafer & Graham, 2002). To take advantage of the high correlation of interaction measures of physiology (the primary source of missing data) and baseline measures (rs > .67), these measures were included as separate variables in the preimputation data set; reactivity scores were formed postimputation. Five sets of imputed data were generated, following Schafer and Graham’s (2002) recommendations. The results reported herein are based on test statistics and p values averaged across these five data sets.

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. Several distributions were skewed and could not be successfully normalized. To guard against inappropriate interpretation of results due to nonnormality, we evaluated all hypothesis tests with adjusted standard errors and model fit indices, computed using the robust maximum likelihood estimation method in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998).

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overreactive Discipline | – | ||||||

| 2. EDA Reactivity | .05 | – | |||||

| 3. HR Reactivity | .39** | .05 | – | ||||

| 4. RSA Reactivity | −.18* | −.03 | −.66** | – | |||

| 5. Emotion experience | −.27** | −.23* | −.06 | .07 | – | ||

| 6. Negative appraisal bias | .35** | .28** | .09 | −.07 | −.52** | – | |

| 7. Child Misbehavior | .35** | .15 | .23* | −.15 | −.50** | .52** | – |

| Min | 1.00 | 0.00 | −7.41 | −4.19 | −284.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max | 7.00 | 18.04 | 27.97 | 1.63 | 423.02 | 0.64 | 112.00 |

| M | 1.82 | 5.18 | 8.91 | −0.37 | 20.73 | 0.16 | 48.73 |

| SD | 1.18 | 2.86 | 6.54 | 0.84 | 138.50 | 0.15 | 30.96 |

Note. EDA = electrodermal activity; HR = heart rate; RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; one-tailed significance tests.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were carried out in three steps. In a series of regression analyses, we first examined (a) whether negative appraisal bias mediates a negative emotion–overreactivity relation or (b) whether negative emotion mediates a negative appraisal bias–overreactivity relation. Analyses were repeated for each measure of emotion: self-report, HR reactivity, EDA reactivity, and RSA reactivity. Next, a more comprehensive model was formed based on the mediation tests. Each significant direct and indirect association between the predictors and overreactivity was included in this model, which was jointly estimated. Third, after the intrapersonal model had been estimated, child effects were estimated by adding child misbehavior as a predictor of each exogenous variable. Statistical tests were evaluated with one-tailed significance criteria, reflecting the directionality of the hypotheses.

Mothers’ Emotion Experience, Negative Appraisal Bias, and Overreactivity

Both mothers’ emotion experience and their negatively biased appraisals of child behavior were significantly associated with overreactive discipline (see Table 1). Furthermore, emotion and negative appraisal bias were significantly associated. A single regression analysis was the next step in determining whether mothers’ emotion experience and negatively biased appraisals mediated one another in predicting overreactive discipline. If the coefficient for one of the predictors dropped in magnitude relative to its correlation with overreactivity, this would suggest that the other predictor was the mediator. In contrast to the significant emotion experience–overreactive discipline relation (r = −.27, p < .01), emotion experience was not uniquely associated with overreactivity (3 = −.12, ns) when negative appraisal bias was simultaneously entered in a regression equation predicting overreactive discipline. The unique association of negative appraisal bias and overreactive discipline, however, was significant (3 = .29, p < .01) and similar to the corresponding bivariate relation (r = .35). These results suggest that negative appraisal bias mediates the relation between emotion experience and overreactivity. A significant Sobel test of the mediated relation further supports mediation (z = 2.46, p < .01).

Autonomic Reactivity, Negative Appraisal Bias, and Overreactivity

Although HR and RSA reactivity were associated with overreactivity and EDA reactivity was associated with negative appraisal bias, none of the autonomic reactivity variables were associated with both negative appraisal bias and overreactivity. Thus, mediation among autonomic measures and negative appraisal bias in predicting overreactivity was not supported.

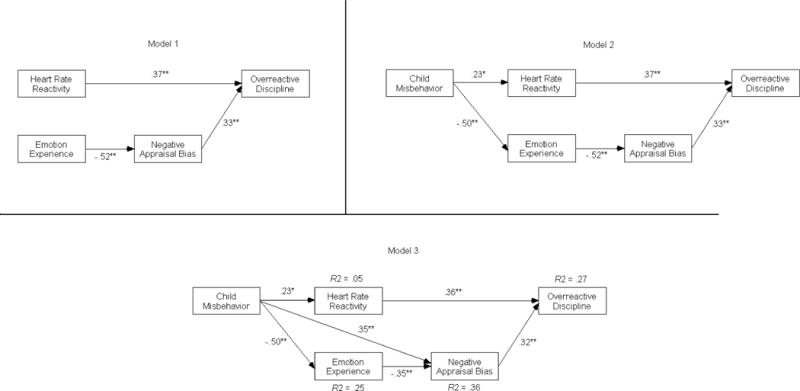

Joint-Prediction Model

The above results suggest two independent paths to discipline: (a) from emotion experience to negative appraisal bias to overreactive discipline and (b) from HR reactivity to overreactive discipline.3 The model, evaluated via path analysis, fit the data well (Model 1 in Table 2 and Figure 1), indicating that HR reactivity predicted overreactive discipline independent of the path from emotion experience to overreactivity as mediated by negative appraisal bias. The Sobel test for the indirect effect of negative emotion experience on overreactivity, by way of its impact on negative appraisal bias, confirmed the apparent mediation (z = 2.10, p < .05).

Table 2.

Model Fit

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .52 | 2 | .79 | 1.00 | 1.19 | .00 |

| 2 | 11.50 | 5 | .05 | .91 | .83 | .12 |

| 3 | 2.30 | 4 | .69 | 1.00 | 1.06 | .00 |

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; χ2 is Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2.

Figure 1.

Path analyses for the prediction of overreactive discipline

Prediction by Child Misbehavior

To test for child effects, we added paths from child misbehavior to mothers’ emotion experience and HR reactivity (Model 2 in Table 2 and Figure 1). This model proved to be a poor fit to the data. The addition of a direct path from child misbehavior to negative appraisal bias (Model 3 in Table 2 and Figure 1), however, significantly improved model fit, showing adequate overall fit, χ2change (1, N = 93) = 11.66, p < .01.4 All paths were significant. Approximately 27% of the variance in overreactivity was explained by this process.

To test each of the indirect paths involving child misbehavior implied by Model 3, we computed additional Sobel tests. All indirect effects were significant, with zs ranging from 1.77 to 2.98 (all ps < .05 or .01). Thus, interacting with misbehaving toddlers may trigger three simultaneous processes. In the first, mothers’ HRs increase, resulting in overreactive discipline. In the second, mothers experience more negative feelings, leading them to negatively misinterpret the toddler’s behavior, which feeds into their discipline. In the third, misbehavior directly affects mothers’ perceptions of their toddlers, thereby increasing overreactivity.

Discussion

Our results indicate that any effect a mother’s experience of negative emotion might have on her use of overreactive discipline appears to be cognitively mediated by her negative appraisal bias. Her emotional state influences her appraisal of the child’s behavior, and she sometimes sees her child’s behavior as negative even though it may be objectively benign. The negative perception of her child’s behavior primes an overreactive response. Hypothesized mediated paths involving negative appraisal bias and autonomic indicators of emotion in predicting overreactivity were not supported. The mothers who exhibited larger increases in HR and decreases in RSA, but not those exhibiting increases in EDA, used more overreactive discipline techniques. However, HR and RSA were not associated with mothers’ negatively biased appraisals. HR reactivity and its respective neural and endocrine substrates may operate outside of the conscious sphere in which cognition was assessed. Research indicates that individuals, particularly women, are generally not good reporters of their own HR (e.g., Katkin, Blascovich, & Goldband, 1981). Cardiac responses may therefore bypass conscious cognitive processing to directly influence behavior.

Mediated child effects are also suggested. The misbehavior of toddlers may trigger a cascade of maternal cognition and emotion that leads to overreactive discipline. Results were consistent with a pattern whereby toddler misbehavior influences overreactive discipline through its influence on mothers’ experienced emotion, HR reactivity, and appraisals of child behavior. The likely influence of child behavior on experienced emotion and HR is consistent with experimental data showing that exposure to negative child affect (a major component of toddlers’ misbehavior) causes mothers to experience negative emotion (E. H. Arnold & O’Leary, 1995). Through its effect on subjective and physiological components of mothers’ emotion and through experienced emotions’ effect on mothers’ appraisals, child misbehavior may further carry forward to influence overreactive discipline. Toddler misbehavior also predicted unique variance in negative appraisal bias, independent of mothers’ experience of negative emotion. This result suggests that child misbehavior also directly influences mothers’ appraisals of their toddlers’ behavior in a nonemotional manner, perhaps through a semantic priming mechanism.

In addition to the questions concerning mediated relations that have been the focus of this article, the bivariate associations reported are important in their own right. They replicate earlier findings and establish new ones. First, in the context of a relatively small literature on cognition, emotion, and overreactive discipline, the replication of associations of overreactive discipline with negative emotion experience (Lorber & Slep, 2005; Smith & O’Leary, 1995) and with negatively biased appraisals of child behavior (Lorber et al., 2003; Murray & Johnston, 2003) is an important contribution to the literature. The negative appraisal bias finding complements better established relations between dysfunctional child-centered attributions for child misbehavior and overreactive discipline (e.g., Slep & O’Leary, 1998). Furthermore, the present study is the first to test the relations between autonomic measures and overreactive discipline. As previously reviewed, two earlier studies have reported an association of autonomic reactivity and physically abusive parenting (Frodi & Lamb, 1980; Wolfe et al., 1983). However, the generalization of physiology–behavior relations from clinical to nonclinical populations has been questioned (e.g., Lorber, 2004). Accordingly, documenting significant associations between cardiac reactivity and the use of overreactive, rather than abusive, discipline underscores the theoretical and predictive value of including physiological responses in the study of more prevalent forms of dysfunctional parenting. Overreactive discipline, although more common than outright physical abuse, is thought to play an etiological and/or maintaining role with respect to child conduct problems (e.g., O’Leary et al., 1999). It is therefore useful to understand the processes that may cause it.

Limitations

Ultimately, experimental manipulations (e.g., E. H. Arnold & O’Leary, 1995; Slep & O’Leary, 1998) will be required to demonstrate causal relations among mothers’ biased appraisals, emotion experience, autonomic reactivity, and overreactivity and child behavior. This is a particularly important qualification because multiple regression models cannot distinguish between mediation and third-variable causation and also because mothers’ emotion experience and appraisals of child behavior were assessed after overreactivity and child misbehavior had occurred rather than in the moment. An especially important caveat with regard to causation is that, although child misbehavior was modeled as a cause of mothers’ cognition, emotion, and discipline, it is also easily conceptualized as an effect. Parent effects on child behavior are well known (e.g., Acker & O’Leary, 1996). Indeed, such effects are the reason to study parenting. Second, overreactivity was assessed via one global rating. This rating was reliable and functioned well to test the relations that had been hypothesized. However, event based coding, perhaps with distinctions between verbal and physical expressions of overreactive discipline, could enable examination of the dynamic interplay among the constructs and might reveal different patterns of relations with the predictors. A final limitation concerns the demographics of our predominantly White and affluent volunteer sample. The results may not generalize to other groups, but understanding how the relations found herein could be moderated by socioeconomic variables seems quite worthy of study. Limitations notwithstanding, we believe that the present findings are valuable tests of theoretically warranted mechanisms by which the variables involved may be associated.

Clinical Implications

Parenting interventions for children’s behavior problems (e.g., Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997) are implicitly rooted in a systemic view of psychopathology, one that is also consistent with the current zeitgeist of developmental psychopathology (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). Psychopathology is viewed as residing not just within the child but also within the mother–child relationship and within their broader context. Despite this systemic focus, relatively little work has focused on altering the parental characteristics that a growing body of research suggests are responsible for, or at least associated with, the very parenting behaviors clinicians seek to change. The small corpus of research on intrapersonal correlates of dysfunctional discipline, including the present investigation, has shown that mothers’ social information processing and emotional responses to their children’s misbehavior could be important targets of treatment.

Current parenting interventions seek to directly impact parents’ behavior. Parents learn techniques and are coached in how to apply them. However, if a parent’s behavior is being driven by cognitive affective factors, such as negative appraisal biases and negative emotion, the failure to change these factors could weaken initial outcomes or affect the durability of treatment gains. Perhaps parenting interventions would be even more effective if they also targeted these parental cognitive-affective characteristics more actively, thus becoming more comprehensive cognitive–behavioral interventions. Parenting researchers have just begun to develop such interventions (Bugental et al., 2002; Sanders et al., 2004), and models to learn from exist in better developed areas of the clinical literature (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1987).

More specifically, the results of the present investigation suggest the possibility that modifying the experiential and physiological components of negative maternal emotion could have beneficial effects. The path analysis results (see Figure 1) indicate that negative emotion experience predicts overreactive discipline via negative appraisal bias and that HR reactivity directly predicts overreactivity. Thus, an intervention that explicitly aims to reduce negative maternal emotion during parent–child interactions could jointly ameliorate three risk factors for overreactive discipline: negative emotion experience, HR reactivity, and negative appraisal bias.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The results of the present investigation highlight the multidetermined nature of overreactivity and the interrelated nature of mothers’ appraisals and experiences of emotion during discipline encounters. Science in this area of inquiry would benefit from future research that tests more fine-grained questions with regard to relations among the constructs studied here. For instance, what are the sequential relations among mothers’ emotional responses, perceptions of their children, and discipline? Are the relations specific to verbal or physical aspects of overreactive discipline? Is the HR reactivity–discipline relation attributable to cardiac–somatic coupling? The clinical relevance of continued research on these questions will be further enhanced by replication in treatment-seeking samples. Because few toddlers are identified by their parents as clinical cases, longitudinal designs that predict which children will eventually become clinically identified cases would be particularly informative. Prospective designs, in combination with experimental studies, will help to disentangle the causal relations among these measures of early family process in predicting conduct problems.

Footnotes

Mean resting HR (71.31 beats per min) was consistent with established adult norms for resting HR (70 beats per min; Larsen, Schneiderman, & Pasin, 1986). Mean skin conductance level (4.11 μS) was near the bottom of the normative range (2–20 μS; Stern, Ray, & Quigley, 2001). Taken together, these findings suggest that mothers were relatively comfortable sitting alone and knowing their toddlers were being cared for responsibly by research staff.

In our previous work (Lorber et al., 2003), we used 10-s intervals for calculating bias scores. This resulted in a highly skewed distribution as most mothers did not have any bias. We reasoned that using 5-s intervals would likely increase the base rate of biased appraisals as it would be more sensitive to capturing smaller disagreements.

A simultaneous regression of overreactive discipline on HR reactivity and RSA reactivity revealed that only HR was uniquely associated with overreactivity. Furthermore, the correlation of HR reactivity and overreactive discipline was higher than the correlation of RSA and overreactivity (p < .01). Therefore, RSA reactivity was excluded from the path analyses.

Computed via the method for comparing Satorra–Bentler χ2 statistics between nested models described by Satorra and Bentler (1999).

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Acker MM, O’Leary SG. Inconsistency of mothers’ feedback and toddlers’ misbehavior and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:703–714. doi: 10.1007/BF01664735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolff L, Acker MM. The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EH, O’Leary SG. The effect of child negative affect on maternal discipline behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:585–595. doi: 10.1007/BF01447663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh KH, Crnic K. Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:301–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, et al. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongard S, Pfeiffer JS, al’Absi M, Hodapp V, Linnenkemper G. Cardiovascular responses during active coping and acute experience of anger. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower GH. Mood and memory. American Psychologist. 1981;36:129–148. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.36.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Blue J, Cortez V, Fleck K, Kopeikin H, Lewis JC, Lyon J. Social cognitions as organizers of autonomic and affective responses to social challenge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:94–103. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovick A, O’Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:243–258. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Forgas JP. The pleasure of possessions: Affective influences and personality in the evaluation of consumer items. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;30:631–649. [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Strongman KT, Magai C. Emotions and behaviour: Data from a cross-cultural recognition study. Cognition and Emotion. 2003;17:881–902. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social-information processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Workman E, Cole PM, Weissbrod C, Kendziora KT, Zahn-Waxler C. Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:23–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Reinhold DP, Zambarano RJ. Mothers’ judgment in moments of anger. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1990;36:465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Ruble DN, Grusec JE, Nixon S. Social cognition in parents: Inferential and affective reactions to children of three age levels. Child Development. 1986;57:879–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich WN, Tyler JD, Clark JA. Personality and psychophysiological variables in abusive, neglectful, and low-income control mothers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:449–460. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodi AM, Lamb ME. Child abusers’ responses to infant smiles and cries. Child Development. 1980;51:238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. A valid procedure for obtaining self-report of affect in marital interaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:151–160. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Svebak S. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia as an index of parasympathetic cardiac control during active coping. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Bargh JA, Lombardi W. Nature of priming effects on categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1985;11:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. The psychology of emotions. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Thompson SM. Effects of mood on mothers’ evaluations of children’s behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;6:300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Katkin ES, Blascovich J, Goldband S. Empirical assessment of visceral self-perception: Individual and sex differences in the acquisition of heartbeat discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;40:1095–1101. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.40.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendziora KT, O’Leary SG. Dysfunctional parenting as a focus for prevention and treatment of child behavior problems. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 15. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey JI. Somatic response patterning and stress: Some revisions of activation theory. In: Appley MH, Trumbull R, editors. Psychological stress: Issues in research. New York: Prentice Hall; 1967. pp. 14–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ. The varieties of emotional experience: A meditation on James–Lange theory. Psychological Review. 1994;101:211–221. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PB, Schneiderman N, Pasin RD. Physiological bases of cardiovascular psychophysiology. In: Coles MGH, Donchin E, Porges SW, editors. Psychophysiology: Systems, processes and applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. pp. 122–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, Arsenio WF. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW. Human emotions: A functional view. In: Ekman P, Davidson RJ, editors. The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF. Autonomic psychophysiology of aggression, psychopathy, and conduct problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:531–552. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF. Validity of video-mediated recall procedures for mothers’ ratings of their own emotion and their children’s behavior. Unpublished manuscript 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, O’Leary SG, Kendziora KT. Mothers’ overreactive discipline and their encoding and appraisals of toddler behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:485–494. doi: 10.1023/a:1025496914522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, Slep AMS. Mothers’ emotion dynamics and their relations with harsh and lax discipline: Microsocial time series analyses. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:559–568. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Wilson MF, Pincomb GA, Edwards GL, Tompkins P, Brackett D. Activation patterns to aversive stimulation in man: Passive exposure versus effort to control. Psychophysiology. 1985;22:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1985.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:683–697. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Johnston C. Mothers’ perceptions of ADHD behaviors: Relation to parenting characteristics and child behavior problems. In: Lorber (Chair) MF, editor. Advances in clinical social–cognitive research on parenting; Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Boston, MA. 2003. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Authors; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary SG, Slep AMS, Reid J. A longitudinal study of mothers’ overreactive discipline and toddlers’ externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:331–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1021919716586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. 4,510,944. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; US Patent. 1985

- Porges SW. Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage: A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB. Prevention of conduct disorder before and after school entry: Relating interventions to developmental findings. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman IJ, Evdokas A. Appraisals cause emotion experiences: Experimental evidence. Cognition and Emotion. 2004;18:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Pidgeon AM, Gravestock F, Connors MD, Brown S, Young RW. Does parental attributional retraining and anger management enhance the effects of the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program with parents at risk of child maltreatment? Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:513–535. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. 1999 doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saul JP, Berger RD, Albrecht P, Stein SP, Chen MH, Cohen RJ. Transfer function analysis of the circulation: Unique insights into cardiovascular regulation. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:H1231–H1245. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (Version 2) [Computer software] University Park, PA: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, O’Leary SG. The effects of maternal attributions on parenting: An experimental analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, O’Leary SG. Attributions and arousal as predictors of maternal discipline. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19:459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Edwards P, McGraw K, Kilgore K, Holton A. Escalation and reinforcement in mother–child conflict: Social processes associated with the development of physical aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Stern RM, Ray WJ, Quigley KS. Psychophysiological recording. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:93–109. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis R, Lovejoy MC. Information processing in everyday life: Emotion-congruent bias in mothers’ reports of parent–child interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:216–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ. Interrater agreement for journal manuscript reviews. American Psychologist. 1984;39:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Fairbank JA, Kelly JA, Bradlyn AS. Child abusive parents’ physiological responses to stressful and non-stressful behavior in children. Behavioral Assessment. 1983;5:363–371. [Google Scholar]