Abstract

Background

Thymic carcinomas are rare cancers with limited data regarding outcomes, particularly for those patients with advanced disease.

Methods

We identified patients with thymic carcinomas diagnosed between 1993 and 2012. Patient characteristics, recurrence free survival (RFS), and overall survival (OS) were analyzed.

Results

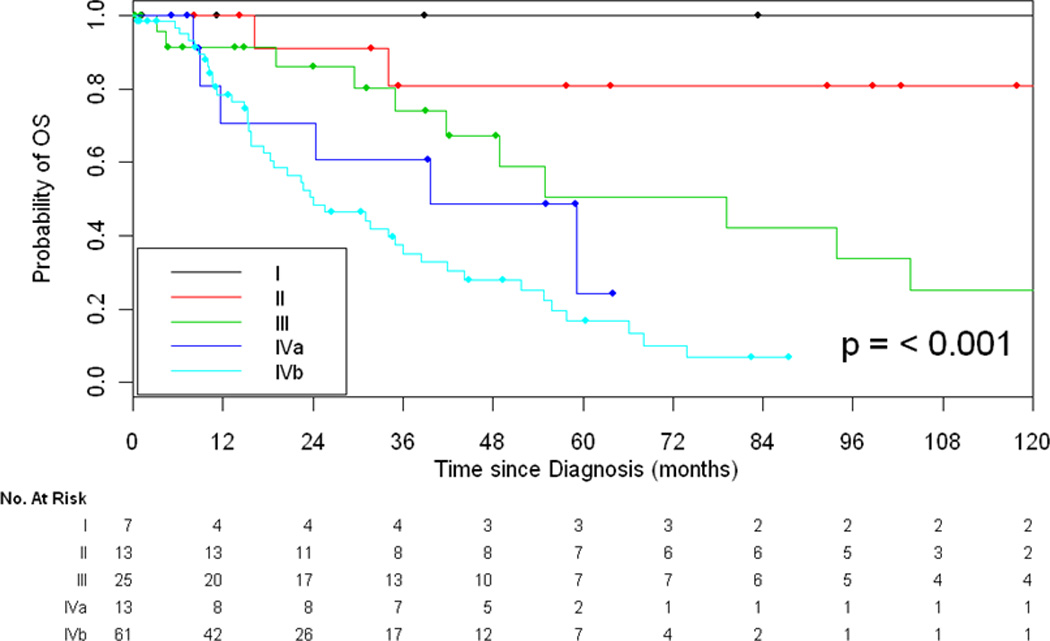

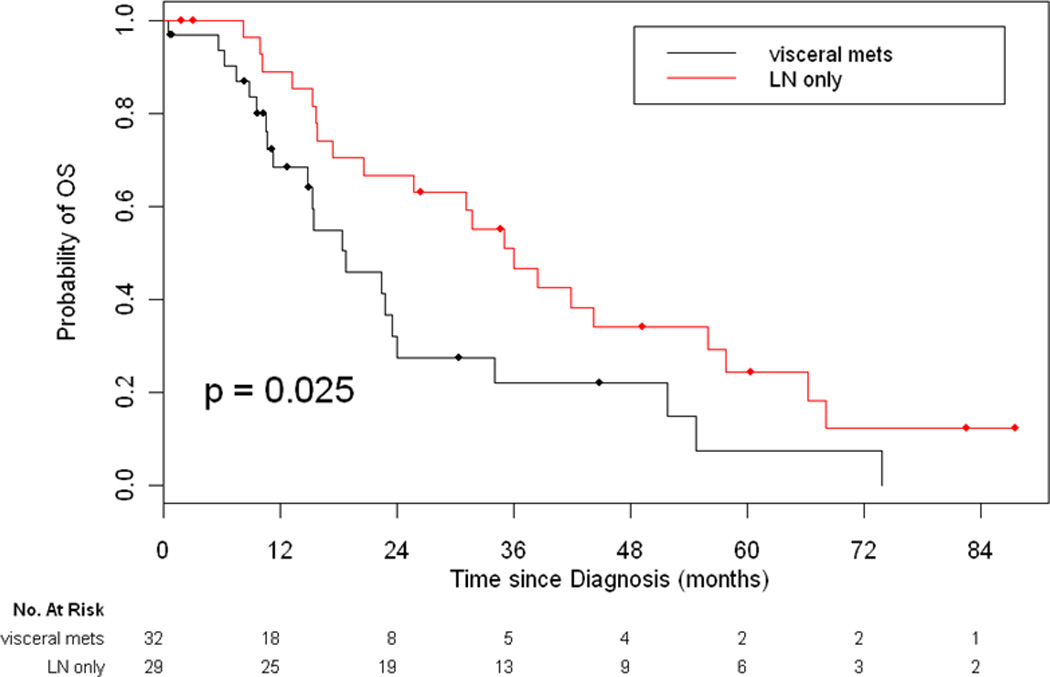

One hundred twenty-one patients with thymic carcinomas were identified. Higher Masaoka stage was associated with worse OS and RFS (5-yr OS of 100%, 81%, 51%, 24%, and 17% for stage I, II, III, IVa and IVb respectively, p<0.001 and 5-yr RFS of 80%, 28%, and 7% for stage I/II, III, and IV respectively, p<0.001). Patients with stage IVb lymph node (LN) only disease had a better 5-year OS as compared to patients with distant metastasis (24% vs. 7%, p=0.025). Of the 61 patients with stage IVb disease, 22/29 patients (76%) with LN-only disease underwent curative intent resection vs. 3/32 patients (9%) with distant metastasis. Twenty-two patients with LN involvement were treated with multi-modality therapy. Three (14%) remain free of disease with long-term follow-up (range: 3.4+ years to 6.8+ years).

Conclusions

We describe the clinical features of a large series of patients with thymic carcinoma in North America. The Masaoka staging system effectively prognosticated OS and RFS. Patients with stage IVb LN-only disease had significantly better OS as compared to patients with distant metastasis with a subset of patients sustaining long term RFS with multi-modality therapy. If validated, these data would support a revised staging system with sub-classification of stage IVb disease into two groups.

Introduction

Thymic carcinomas are rare tumors, representing only 15 to 20% of all thymic neoplasms with fewer than 500 cases diagnosed in the United States per year.1,2 As such, most of the literature on thymic carcinomas comes from retrospective reviews of surgical series, often from countries in Asia, where thymic carcinoma appears to be more prevalent.3–16 Data is limited regarding the clinical characteristics and clinical behavior in a western population, particularly in patients with advanced disease who are not surgical candidates.

Because of the rarity of the disease and absence of prospective data, there is no overall consensus about the ideal staging system for thymic carcinomas. The Masaoka staging system is widely used to stage thymomas as it can predict for overall survival in this disease. However, several groups have reported that similar results are not seen in thymic carcinomas.6,13,15,17–19 These authors evaluated mostly small surgical series and showed that survival differences were observed only when comparing early versus advanced Masaoka stage or when other anatomical factors, such as involvement of the great vessels, were taken into account.6, 18–21 Ruffini et al recently showed good prognostic stratification among Masaoka staging, although stages I and II were again grouped together because of a similar survival.22 A TNM based staging system has been proposed for thymic carcinomas—however this staging system has thus far failed to show significant survival differences in several studies.23–24

In this study, we describe our experience in the management of 121 surgical and non-surgical cases of thymic carcinomas evaluated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center over a 20 year period. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of patients with thymic carcinoma and to identify prognostic factors of survival. Based on a pre-review of our institutional experience, we hypothesized that the Masaoka staging system can effectively prognosticate overall and recurrence free survival and that those patients with stage IVb lymph node only disease would have longer survival as compared to patients with distant metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We identified all consecutive patients diagnosed with thymic carcinoma between January 1, 1993 and December 31, 2012 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Patients with thymomas, well differentiated thymic carcinomas (type B3 thymomas), thymic carcinoid tumors, or thymic small or large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas were excluded from this analysis. This cohort of patients includes the 23 patients described by Huang et al and Bott et al.9.25 All pathology specimens were reviewed at MSKCC to confirm the diagnosis. Approval for this retrospective chart review was obtained from the institutional review board at MSKCC.

Data Collection

Patient characteristics and outcomes including age, race, sex, smoking history, evidence of paraneoplastic syndromes, stage, treatment details including use of chemotherapy, surgery, and/or radiation, recurrence data, and last date of follow-up/date of death were abstracted from medical records manually and analyzed retrospectively. Pre-operative imaging was regularly performed with a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Staging was characterized according to Masaoka staging.26 Total thymectomy, with or without en bloc resection of adjacent structures performed through a median sternotomy, was the standard procedure for resection of thymic carcinoma during the study period. Lymph nodes were staged using N0 and N1 categories as extensive nodal dissections were not routinely performed in a systematic manner. Resection status was evaluated using operative and pathology reports. Resection status was characterized as R0 if all margins were microscopically negative, R1 if margins were microscopically positive, or R2 if grossly incomplete resection was performed. Follow up status was obtained from institutional records and verified by the Social Security Death Index. Recurrence was defined as clinical appearance of new disease by imaging and/or pathology after curative intent resection. Type of recurrence, either local (mediastinal), intrathoracic (lung/pleura), or distal (extrathoracic) was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Two endpoints were investigated: overall survival (OS) in the full cohort and time to recurrence in the subset of patients who had a curative intent surgery. Both endpoints were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and univariate associations between patient, disease or treatment factors and survival were analyzed using the log-rank test. OS was defined as the time from pathologic diagnosis until death by any cause. Time to recurrence was defined as the time from surgical resection until the date of imaging confirming recurrence of disease. In each analysis, patients who did not experience the event of interest during the study time were censored at the date of the last available follow-up. All statistical tests were two-sided and used a 5% significance level. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.0.1; R Development Core Team), including the “survival” and “survcomp” packages.

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred and twenty-one patients were diagnosed with thymic carcinoma during the study period. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The majority of patients with thymic carcinoma presented with locally advanced (III, IVa) or metastatic disease at diagnosis, with squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histologic subtype. Three patients developed concurrent dermatomyositis and one patient developed limbic encephalitis with positive anti-VGKC antibodies during their clinical course. Myasthenia gravis was not seen in any patients. On univariate analyses, age, sex, smoking history, and the presence of a paraneoplastic syndrome were not associated with OS.

Table 2.

Individual Patient Characteristics of the Stage IVb Patients who are Currently NED

| Patient | Age (years) |

Sex | Pack years |

Race | Histology type |

Masaoka Stage at diagnosis |

Treatment | Areas of metastasis |

Recurrence | Disease free survival since resection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | F | 12 | Asian | Squamous | IVb | Resection/XRT/neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Lymph node (no visceral metastasis) | No | 6.8 years+ |

| 2 | 43 | F | 0.6 | White | Lympho-epithelioma-like carcinoma | IVb | Resection/XRT/neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Lymph node (no visceral metastasis) | No | 3.4 years+ |

| 3 | 82 | M | 0 | White | Lympho-eptihelioma-like carcinoma | IVb | Resection/XRT/neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Lymph node (no visceral metastasis) | Yes: local recurrence to mediastinum. Pt treated with resection. | 4.9 years+ |

Overall Survival by Stage

Stage at initial diagnosis was associated with OS (p<0.001, Figure 1). Five-year OS was 100%, 81%, 51%, 24%, and 17% for stage I, II, III, IVa, and IVb, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overall Survival Based on Stage at Diagnosis

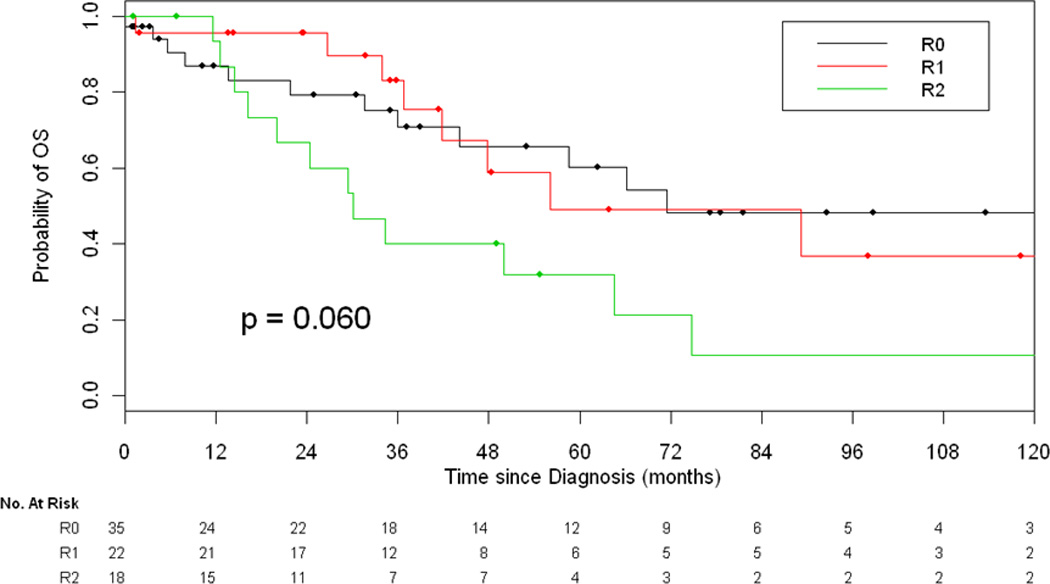

Overall Survival Based on Type of Resection

Of the 121 patients analyzed, 77 patients underwent resection with curative intent. Two patients had surgical resections outside of MSKCC and the details of the resection could not be assessed. Complete tumor resection with pathologically confirmed negative resection margins (R0) was achieved in 35 (47%) patients. 22 (29%) patients had microscopic residual disease (R1), and 18 (24%) patients had gross residual disease (R2). 48% of patients with an R0 resection underwent adjuvant mediastinal radiation as compared to 94% and 88% for R1 and R2 resections, respectively. OS was significantly improved for patients who had a R0 or R1 resection versus a R2 resection (p=0.018, Figure 2). 5-year OS was 60%, 49% and 32% for R0, R1 and R2 resection, respectively.

Figure 2.

Overall Survival Based on Type of Resection

Overall Survival Based on Distant Metastasis versus Lymph Node Only Involvement

Sixty-one patients were diagnosed with stage IVb disease at initial diagnosis. Twenty-nine patients had lymph node involvement without distant metastasis. Of the 29 patients, 14 patients had preoperative findings of enlarged lymph nodes by imaging and 15 patients were diagnosed with positive lymph nodes after pathology review of the resected specimen. Thirty-two patients had distant metastatic disease (69% had lung metastasis, 41% had bone metastasis, and 31% of patients had liver metastasis involvement at presentation). Of the 61 patients with stage IVb disease, 22/29 patients (76%) with lymph node only involvement underwent resection as compared to 3/32 patients (9%) with distant metastasis (p<0.001). Stage IVb patients with lymph node involvement had a better 5-year OS as compared to patients with distant metastasis (24% vs. 7%, p=0.025, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overall Survival for Patients with Stage IVb Disease Based on Metastatic Site

Management of Early Stage Disease

Our series included 7 patients with stage I disease and 13 patients with stage II disease. All patients with stage I and stage II disease were treated with resection. All patients with stage I disease had an R0 resection as compared to 69% of patients with stage II disease. None of the stage I patients received additional perioperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Nine of the 13 patients with stage II disease received adjuvant mediastinal radiation, including all patients with a R1 resection. Five-year OS was 100% and 81% for stage I and II disease, respectively.

Management of Locally Advanced, Resectable Disease and Role of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

We assessed outcomes in locally advanced disease, including all stage III patients and selected patients with stage IVa–IVb disease with intrathoracic involvement that were treated with curative intent resection. This included a total of 54 patients. Thirty-seven patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery while 17 patients received initial surgery. Of the 37 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 39% of these patients had a R0 resection as compared to 21% of patients with upfront surgery (p=0.095). Most neoadjuvant chemotherapy administered was platinum based.

Management of Unresectable Locally Advanced or Metastatic Disease

Forty-four patients including 4 patients with stage III disease, 3 patients with stage IVa disease, and 37 patients with stage IVb disease were felt to be unresectable. Of these 44 patients, 13 received chemoradiation, 20 received palliative chemotherapy, 2 received palliative radiation and 9 were lost to follow up and/or received no further treatment. Median overall survival for these patients was 19 months (95% CI 15, 31).

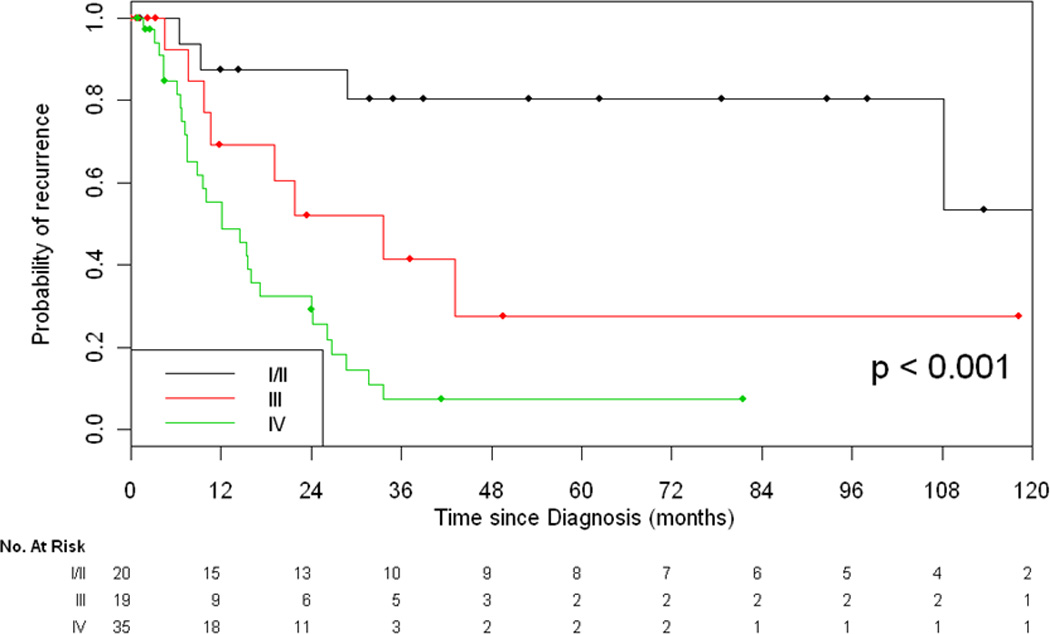

Recurrence

Of the 74 evaluable patients who had potentially curative resection and recurrence data available, 40 patients (53%) had recurrence or disease progression. Stage at initial diagnosis was significantly associated with rate of recurrence (p<0.001, Figure 4). 4 of 20 patients (20%) with initial stage I/II disease recurred as compared to 36 of 54 patients (67%) with locally advanced disease (stage III, IVa, or IVb disease). Median time to recurrence was 11 months (range, 2 –108 months). 13% of patients recurred in the mediastinum, 48% of patients recurred in the thorax (pleura and lung), and 39% recurred distally. Distant sites included lung, bone, and liver. Brain metastases were identified in 2 patients.

Figure 4.

Recurrence-Free Survival Based on Stage

Multimodality Therapy in Stage IVb Disease with Lymph Node Involvement

Twenty-two patients with stage IVb disease received multi-modal therapy including curative-intent resection, mediastinal radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Thirteen of these 22 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with post-operative mediastinal radiation, 6 received adjuvant chemotherapy and post-operative mediastinal radiation, and 3 patients received post-operative mediastinal radiation without chemotherapy. Of these patients, 3/22 (14%) are currently free of disease with long-term follow-up (see Table 3). One patient had a local recurrence 16 months after definitive resection, had the recurrence resected, and has been free of disease for over 4.9 years.

Discussion

Our study represents one of the largest reported series of patients with localized as well as advanced, unresectable disease treated in North America. The results of our study indicate several important findings: 1) The Masaoka staging system predicts likelihood of overall and recurrence free survival; 2) patients with stage IVb lymph node-only disease have a better overall survival as compared to patients with distant metastasis; and 3) for a subset of patients with stage IVb lymph node only disease, treatment with multi-modality therapy including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation can result in a long term recurrence free survival. These data should prompt consideration of a revised Masaoka staging system with sub-classification of stage IVb disease into two groups if supported by data in the International Thymic Malignancies Interest Group staging database.

For patients who undergo surgical resection, our data support the importance of an R0 resection. Specifically, we showed that a R0 or R1 resection is associated with improved overall survival, as compared to an R2 debulking procedure. The similar survival curves for R0 and R1 resections could be explained by the fact that most patients with a R1 resection received adjuvant radiation therapy.

For patients with advanced disease, a multidisciplinary approach, including the collaboration of radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, oncologic surgeons, pathologists, and radiologists may be considered in the comprehensive management of these complicated patients. We showed that platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy can potentially improve the rates of R0 resection, although a randomized clinical trial would need to be performed to confirm these results.

Finally, our results demonstrate that myasthenia gravis is an incredibly rare event in thymic carcinoma. Although myasthenia gravis is diagnosed in up to 50% of patients with thymomas, this autoimmune paraneoplastic disorder was not detected in any of the 121 patients with thymic carcinomas evaluated.27 Others report that patients with thymic carcinoma can present with myasthenia gravis.3,7,22 However, we believe that when this autoimmune phenomenon is present, the diagnosis of thymic carcinoma needs to be reconfirmed and thymoma ruled out.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. The main strength of this study is that it represents one of the largest series of patients with localized as well as advanced, unresectable disease treated in North America. Furthermore, all biopsies and surgical specimens obtained were reviewed by expert pathologists in one center. It is well known that there is significant inter-observer variation in the classification of thymic tumors making central pathology review essential for accuracy.28 Additionally, patients with thymomas and well differentiated thymic carcinomas (B3 thymomas) were excluded from the analysis. Many studies have grouped thymic carcinomas and thymomas in the same analysis based on past histologic classifications. However, the latest WHO histologic classification observes that thymic carcinomas are a distinct group of thymic malignancies and recommends they be analyzed separately.29 Finally, as data was collected from one center, information regarding clinical characteristics, recurrences, resection status, and chemotherapy responses were readily available for most patients. As with previously reported reviews of thymic carcinoma, our study is limited by the retrospective nature of the data collection and heterogeneity of treatments. Furthermore, our median follow-up time was 24 months, and a longer follow-up may provide more data regarding late recurrences.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the Masaoka staging system can prognosticate overall and recurrence free survival. Our data suggests that patients with stage IVb lymph node disease may have a better overall survival as compared to patients with distant metastasis and can achieve long term disease free survival with multi-modality therapy. Rates of recurrence are high at all stages of disease, with distant disease in the liver, bone, and lungs commonly seen. Thus, prospective trials and collaborative efforts are necessary in the future to evaluate and compare therapies to improve outcomes in this rare disease.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (N=121)

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 58 (12–84) |

| Women | 52 (43%) |

| Race | |

| White | 91 (75%) |

| Asian | 14 (12%) |

| Black | 11 (9%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2%) |

| Other | 2 (2%) |

| Smoking Status | |

| Never smokers | 74 (61%) |

| Light smokers (≤15 pack years) | 16 (13%) |

| Heavy Smokers (>15 pack years) | 31 (26%) |

| Masaoka Stage at diagnosis | |

| Stage I | 7 (6%) |

| Stage II | 13 (11%) |

| Stage III | 25 (21%) |

| Stage IVa | 13 (11%) |

| Stage IVb | 61(50%) |

| Undeterminate stage | 2 (2%) |

| Paraneoplastic syndrome | |

| Dermatomyositis | 3 (3%) |

| Anti-VGKC antibodies | 1 (1%) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 0 (0%) |

| Histologic subtype | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 65 (54%) |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 32 (27%) |

| Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma | 9 (7%) |

| Basaloid Carcinoma | 7 (6%) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 1 (1%) |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | 1 (1%) |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 2 (2%) |

| Carcinoma w/ neuroendocrine features | 4 (3%) |

| C- kit mutation | 3/19 (16%) |

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: Biostatistics Core grant (P30 CA008748)

References

- 1.Greene MA, Malias MA. Aggressive multimodality treatment of invasive thymic carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;2:434–436. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venuta F, Anile M, Diso D, et al. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filosso PL, Guerrera F, et al. Outcome of surgically resected thymic carcinoma: A multicenter experience. Lung Cancer. 2014;83:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Zhao H, et al. Surgical treatment and prognosis of thymic squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 105 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosai SJ. Thymic carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 60 cases. Cancer. 1991;67:1025–1032. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<1025::aid-cncr2820670427>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissferdt A, Moran CA. Thymic carcinoma, part 1: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 65 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:103–114. doi: 10.1309/AJCP88FZTWANLRCB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu HC, Hsu WH, Chen YJ, et al. Primary thymic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yano M, Sasaki H, Yokoyama T, et al. Thymic carcinoma: 30 cases at a single institution. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:265–269. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181653c71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Rizk NP, Travis WD, et al. Comparison of patterns of relapse in thymic carcinoma and thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalabreysse L, Etienne-Mastroianni B, Adeleine P, et al. Thymic carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistological study of 19 cases. Histopathology. 2004;44:367–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu CP, Chen CY, Chen CL, et al. Thymic carcinoma. Ten years' experience in twenty patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:615–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimosato Y, Kameya T, Nagai K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the thymus. An analysis of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1977;1:109–121. doi: 10.1097/00000478-197706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa K, Toita T, Uno T, et al. Treatment and prognosis of thymic carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 40 cases. Cancer. 2002;94:3115–3119. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazuya K, Yasumasa M. Therapy for thymic epithelial tumors: a clinical study of 1,320 patients from Japan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:878–884. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okereke IC, Kesler KA, Freeman RK, et al. Thymic carcinoma: outcomes after surgical resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1668–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weksler B, Dhupar R, Parikh V, et al. Thymic carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of factors predictive of survival in 290 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo K, Monden Y. Therapy for thymic epithelial tumors: a clinical study of 1,320 patients from Japan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:878–884. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng YL, Wang ST, Wu MH, Lin MY, Lai WW, Cheng FF. Thymic carcinoma: involvement of great vessels indicates poor prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1041–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg D, Burt ME, Bains MS, et al. Thymic carcinoma: current staging does not predict prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:303–308. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosaka Y, Tsuchida M, Toyabe S, Umezu H, Eimoto T, Hayashi J. Masaoka stage and histologic grade predict prognosis in patients with thymic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CY, Bae MK, Park IK, Kim DJ, Lee JG, Chung KY. Early Masaoka stage and complete resection is important for prognosis of thymic carcinoma: a 20-year experience at a single institution. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruffini E, Detterbeck F, Raemdonck DV, et al. Thymic Carcinoma: A Cohort Study of Patients from the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. J Thoracic Oncol. 2014;9:541–548. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuchiya R, Koga K, Matsuno Y, Mukai K, Shimosato Y. Thymic carcinoma: proposal for pathological TNM and staging. Pathol Int. 1994;44:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissferdt A, Moran CA. Thymic carcinoma, part 2: a clinicopathologic correlation of 33 cases with a proposed staging system. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:115–121. doi: 10.1309/AJCPLF3XAT0OHADV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bott MJ, Wang H, Travis W, et al. Management and outcomes of relapse after treatment for thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(6):1984–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, et al. Follow up study of thymomas with special reference to their clinical stages. Cancer. 1981;48:2485–2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811201)48:11<2485::aid-cncr2820481123>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romi F. Thymoma in myasthenia gravis: from diagnosis to treatment. Autoimmune Disease. 2011;2001:474512. doi: 10.4061/2011/474512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verghese ET, den Bakker MA, Campbell A, et al. Interobserver variation in the classification of thymic tumours—a multicentre study using the WHO classification system. Histopathology. 2008;53:218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx A, Strobel P, Zettle A, et al. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the lung, thymus, and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press; Thymomas. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; pp. 152–153. [Google Scholar]