Abstract

While the right to health is increasingly referenced in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) discussions, its contribution to global health and development remains subject to considerable debate. This hypothesis explores the potential influence of the right to health on the formulation of health goals in 4 major SDG reports. We analyse these reports through a social constructivist lens which views the use of rights rhetoric as an important indicator of the extent to which a norm is being adopted and/or internalized. Our analysis seeks to assess the influence of this language on goals chosen, and to consider accordingly the potential for rights discourse to promote more equitable global health policy in the future.

Keywords: Right to Health, Global Health Policy, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Introduction

As Member States negotiate a new global development agenda in New York in September 2015, there will be much attention on their chosen health goal(s). For better or worse, the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) experience illustrates that new goals will shape global health resources and priorities for the next 15 years. Since at least 2012, the SDG agenda currently tabled at the United Nations (UN) has been formulated through various processes which have debated whether the health goals should incrementally expand existing MDGs that added select health interventions such as non-communicable diseases (NCDs), or significantly expand towards systematic health systems improvement through universal health coverage (UHC). The latter is an ambition considerably closer to the right to health imperative of assuring available, accessible, acceptable and good quality health and healthcare for all.

Indeed, UN officials, advocates, and policy-makers argue for a human rights consistent approach to developing these goals. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon contends that a “global development agenda based on human rights and the rule of law is the surest pathway to balancing the needs of people and the planet, while eradicating extreme poverty and closing socio-economic gaps.”1 In relation to health, there are increasing calls for new global goals to realize, and be guided by, the human right to health.2 These calls are motivated by the growing legal, political and social force of this right, amplified by AIDS treatment campaigns during the 2000’s which achieved broad acceptance of access to antiretroviral drugs as a fundamental human right, and “sharpened awareness of the importance of health equity, gender equality and human rights—in their own right and for public health.”3 These gains build on a longer-standing recognition that human rights-based approaches to health-related policy and programming offer mutually reinforcing benefits for both health and human rights.4-6

The adoption in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of an explicit human rights and right to health focus would sharply contrast with how human rights were dealt with in the MDGs. Although states affirmed their commitment to “upholding respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms” in the 2000 Millennium Declaration,7 the MDG process that followed showed little awareness or sustained engagement with human rights.8 Indeed, the MDGs were criticized for being created in a non-deliberative, non-transparent, non-inclusive top-down process,8,9 and for dropping targets with “a strong human rights orientation—such as affordable water, fair trade, and support for orphans.”10 Sexual and reproductive health illustrates the potential impact of a disjuncture with rights: despite global recognition of these rights in the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development and the 1995 Beijing Platform of Action, conservative opposition saw women’s health rights reduced to a maternal mortality goal in the MDGs,11 with a formal reproductive health target only added in 2007 after a significant advocacy effort.12

While the right to health is increasingly referenced in SDG debates, its usage varies and it is not always clear whether and how rhetorical references are related to proposed health goals. In this paper, we attempt to assess whether and how right to health language is related to the health goals proposed in reports. We analyse 4 major SDG reports against the backdrop of the growing legal force of this right and through a social constructivist lens which views rights rhetoric as an important indicator of the extent of adoption/internalization of a norm.

Background

The growing codification and interpretation of the right to health juxtaposed with the ever-increasing integration of human rights-based approaches in development and public health spheres,offers increasingly specific standards to guide a more equitable health goal agenda.3 International law has recognized individual rights and state obligations towards health at least since 1946 when the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO Constitution) established “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental right of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic, or social condition.”13 The right to health was further developed in the iconic 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which recognized every person’s right to a standard of living adequate for their health and well-being, including medical care.14 The most authoritative protection of the right to health is found in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (‘the Covenant’), where state parties recognize everyone’s right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health, and agree to take a number of steps to achieve this including reducing infant mortality, addressing infectious disease and assuring medical service to all in sickness.15 In addition, this right is codified in multiple other international and regional treaties16-19 and in at least 115 domestic constitutions.20,21

This proliferation has contributed to the right to health’s mounting legal, social, and political force. This growth is particularly aided by an authoritative interpretation of the right to health by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ (‘the Committee’ or ‘UNCESCR’), moving this right far beyond the legal vagueness plaguing its early years. In the Committee’s General Comment 14 issued in 2000, the right to health is concretely interpreted to include rights to adequate healthcare and the underlying determinants of health, and to place corresponding obligations on governments to act on health at home and where able, abroad.22 Growing legalization and specificity has seen a corresponding surge in domestic right to health litigation over the last twenty years.23,24 A recently adopted “Optional Protocol” to the Covenant has created the first quasi-enforceable accountability mechanism for the right to health at the international level, giving the Committee the authority to review individual complaints of rights violations.

Yet the contribution of rights may be more subtle and discursive than this. Social constructivist theorists argue that ideas (rather than material facts) are the primary constituents of interests and power, and that language is intimately connected to this ideational power.25 Thus, when actors use particular language to ‘frame’ an issue, they may connect with a set of deeper paradigms which “influence (often unconsciously) the ways in which actors think and talk about global health problems.”26 The concept of ‘framing’ draws from a longer social science tradition of research in the realms of communication studies,27 policy studies and agenda-setting28,29 and social movements.30,31 Framing is understood to denote a “schemata of interpretation”30 that provides “linguistic, cognitive and symbolic devices … to identify, label, describe and interpret problems and to suggest particular ways of responding to them.”32 How framing works as a mode of interpretation is illustrated in the social movement use of ‘injustice frames,’ which identify victims and sources of causality, blame and culpable agents.31 Conversely, ‘human rights frames’ would tend to identify the bearers of entitlements and duties, specify the range of actions and outcomes required accordingly, and to locate those entitlements and duties within legally binding international law. Actors using the rhetoric of the right to health would implicitly evoke this normative paradigm.

While states may adopt rhetoric for political purposes, once they do, they can become ‘tripped up’ by their own language in a form of ‘argumentative self-entrapment,’33 since once states rhetorically accept a norm rather than deny it, it is that much harder to deny the action required to fulfil that norm. In this light, even the most cynical use of rights language may unwittingly advance the acceptance and internalization of related norms, and connect drafters with deeper normative paradigms that subtly shape potential policy solutions accordingly.34

Methods

We tested the proposition that the use of rights language may shape policy solutions by comparing the health goals in four SDG reports with the extent of right to health language used in each report. We focused on the four most significant reports issued through the post-2015/SDG negotiation process: the April 2013 report of the Global Thematic Consultation on Health (GTCH)35; the May 2013 report of the ‘High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda’ (HLP)36; the October 2013 report of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)37; and 2014 report on SDGs of the Open Working Group.38 Where final reports relied on proposals made in earlier area-specific technical reports on health goals, (as with the SDSN and OWG reports), we included those reports in our content analysis.

Our aim was to assess whether the use of right to health language was associated with health goals and targets proposing UHC, given our belief that this concept has a strong affinity with the normative prescriptions of the right to health.39 While caution about the conditions in which UHC could realize this right is appropriate,40,41 we consider the fact that key actors in the SDG process also view UHC as a relative proxy for the right to health as sufficient justification to do so here. For example, in 2012, the UN General Assembly called on all states to realize UHC while reaffirming the right to health.42 That same year, the WHO contended that UHC is “by definition, a practical expression of the concern for health equity and the right to health,”43 while Jeffrey Sachs, the chair of the SDSN, argued that UHC is “deeply embedded” in international law.44

We undertook a content analysis involving a word-frequency count of rights language (search terms included “human rights,” “right to health,” “right to development,” and “sexual and reproductive health and rights”). We searched for international human rights instruments using full titles (including “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” and “General Comment 14”). While word count provides an important indicator of the priority given particular terms and concepts, frequency cannot substitute for analysis of how a term is used.45 To achieve this more contextual analysis, we first investigated the substantive nature of such references by comparing the relative frequency of right to health word counts between reports with whether health goals and targets included UHC. Second, we considered how respective processes and participants producing each report may have influenced substantive content adopted.

Results

We found that each report proposes similar overarching health goals: ‘Maximize Healthy Lives,’ ‘Ensure Healthy Lives,’ ‘Achieve Health and Well-being at All Ages,’ and ‘Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-being at All Ages.’ Differences become apparent in subsidiary targets, particularly regarding UHC. The GTCH Report proposes accelerating progress on existing health MDGs, reducing major NCDs, and advancing UHC and access as “a goal in its own right.” The SDSN Report similarly proposes ensuring universal access to primary healthcare, ending preventable child and maternal deaths and from NCDs, and promoting healthy diets and physical activity. The Open Working Group Report proposes nine targets that extend the MDGs and add new goals on NCDs, mental health, sexual and reproductive health rights, road traffic accidents and UHC. In contrast, the HLP Report proposes incorporating existing MDGs and adding new targets on vaccinations, neglected diseases and NCD. UHC is not included as a health target, with the HLP emphasizing that while it focused on health outcomes, it recognized that achieving these outcomes requires “universal access to basic healthcare.”38

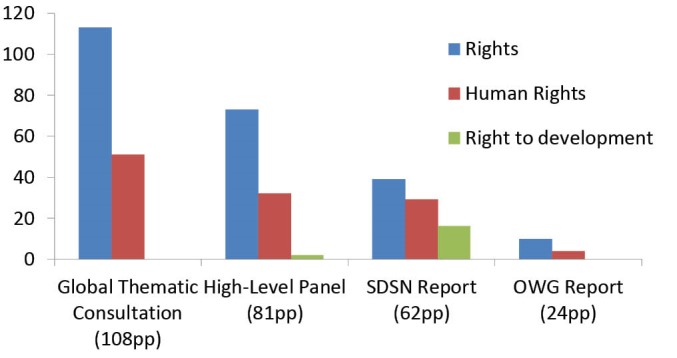

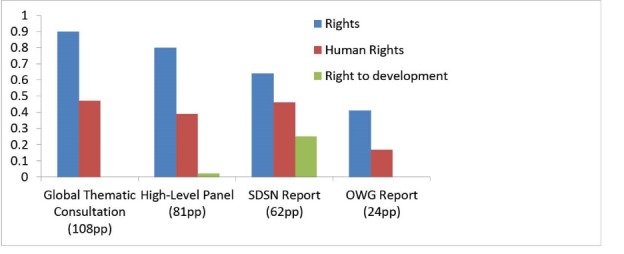

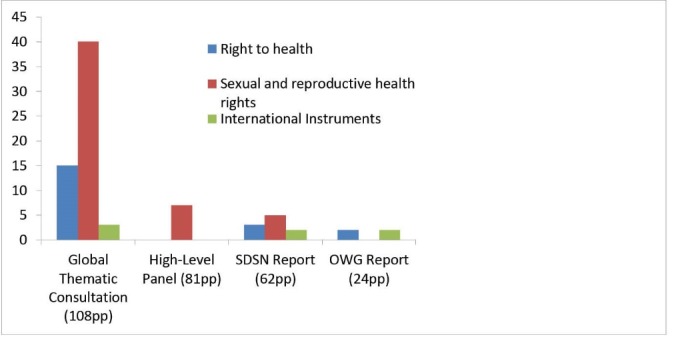

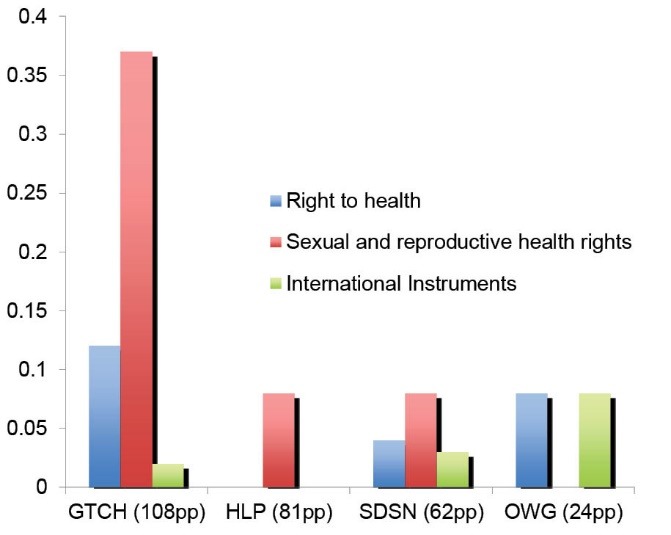

As Figure 1 illustrates, rights-relevant terms appear in each report with relative frequency, ranging from over 100 instances in the 108 page GTCH Report, over 70 instances in the 81 page HLP Report, almost 40 in the 62 page SDSN Report and 10 in the 24 page OWG Report. As Figure 2 illustrates, these variations are not significant taking into account varying report lengths, albeit that the OWG Report is on the lower end of this trend. Yet we found stark differences in the use of the term “right to health” that document length does not necessarily explain (Figures 3 and 4), although contrasting foci and background processes may provide some insights. As Figures 3 and 4 indicate, the GTCH report (the only health-specific report) far outstrips any of the other reports in its references to health rights. The GTCH Report refers to the right to health and related language at least 15 times, identifies treaty sources for the right to health, including the Covenant and General Comment 14,37 and extensively refers to “sexual and reproductive health rights,” which appear 40 times in various forms. This report also uses the right to health to expressly frame its health goals, suggesting that since health is a human right, it should be prominent within post-2015 deliberations. It is to be expected that a stand-alone report on health would have more references to health-related rights than the more general reports. In addition, the process driving its development may have also assured that a right to health approach was strongly pushed to the fore, since the GTCH report relied heavily on civil society and UN interventions, condensing primary messages from background papers and a web-based consultation with over 100 papers from individuals, UN organizations, governments, research centres, civil society, and the private sector.46

Figure 1.

Human Rights Word-Counts in the Four Reports.

Figure 2.

Human Rights Word-Counts per Page in the Four Reports.

Figure 3.

Right to Health Word-Counts in the Four Reports.

Figure 4.

Right to Health Word-Counts per Page in the Four Reports.

Conversely, the SDSN Report refers to “sexual and reproductive health rights” five times but ignores the “right to health.” This elision is offset by the fact the SDSN’s health goal and targets are drawn from an earlier technical report that referenced the right to health three times, referred to human rights instruments (including the Covenant), and devoted an appendix to exploring UHC’s human rights and equity foundation.47 Moreover, this technical report was produced by the ‘health for all’ thematic group (one of twelve groups informing the SDSN report), a name implying a normative bent towards universalism, and comprised primarily of representatives from academia and civil society, actors potentially more inclined to advocate for a rights-based approach.

The OWG Report uses rights and human rights-related terms fairly frequently, although makes no explicit reference to the right to health or to sexual and reproductive health rights. However, here too the absence of these terms is offset by an earlier technical brief on health, cited within the OWG Report, which expressly references sexual and reproductive health and rights, and cites the right to health and its treaty representations, premising health’s centrality to sustainable development on the fact that “health is a right and a goal in its own right.”48 This focus on the right to health is likely explained by the fact that the health and population dynamics cluster which produced this paper was lead by UN agency and international non-governmental organization (NGO) participants who developed the technical paper from background papers, and statements and presentations made at a special session on health (one of eight sessions on thematic and cross-cutting issues informing the final OWG report).

In contrast, the HLP Report never explicitly references the “right to health” nor identifies related treaties. If health is a human right, it is only implicitly so. At the same time, the report distinguishes ‘universal’ from ‘fundamental’ human rights, with illness and poor healthcare categorized within the former. The HLP defines fundamental rights to include “freedom from fear, conflict and violence,” personal security, and access to sexual and reproductive health rights. This schismatic approach to rights reproduces an historic ideological split in human rights law by prioritizing civil and political rights over economic and social rights (a division redressed in the 1993 Vienna Declaration on Human Rights). Moreover, the Panel reproduces this schism by locating sexual and reproductive health rights within ‘fundamental’ rights, an illogical privileging of one (admittedly key) element of the right to health over all others. This out-dated and ruptured approach to human rights is problematic in itself. However, we believe it is no coincidence that the HLP’s de-prioritization of the right to health is accompanied by UHC’s exclusion: UHC’s omission suggests how actors frame ‘a problem’ may influence how these actors (and their audiences) think about potential solutions. Accordingly, we suspect that the HLP may ‘fear’ that the use of right to health language could be allied with a commitment to its normative prescriptions.

We note too that in contrast to the SDSN and OWG reports, the HLP did not commission a stand-alone background paper on the health goals, an omission which suggests a low priority for health amongst panellists. Moreover, while the Panel’s terms of reference required it to consider findings that included reports from the global thematic consultations, the HLP ignored the GTCH’s proposed health goals and right to health framing. We believe that these exclusions might be explained by the ‘high level… eminent persons’ type composition of the panel, which included three sitting heads of government as chairs (from Indonesia, Liberia, and the United Kingdom), two former heads of government (from Japan and Germany) and six sitting ministers (three of finance and one each of foreign affairs and trade, the environment and international development). We surmise that high-level policy-makers of this kind might be inclined towards conservative approaches to human rights that exclude ostensibly ‘expensive’ rights like health.

Yet as all our figures illustrate, these same actors were not resistant to human rights language more generally, nor to sexual and reproductive health rights, which are distinctly capable of provoking ideological and/or religious opposition. The inclusion of sexual and reproductive health rights in the HLP Report may reflect the success of a longer-standing advocacy campaign to mobilize support in first the MDGs and then SDGs.11,12 This inclusion foreshadows how important social advocacy will be in fomenting political support for the right to health in global health policy arenas, an insight bolstered by the comparably greater inclusion of this right in reports with more civil society and academic participation.

Conclusion

Each of the four reports propose health goals largely consistent with right to health imperatives: the goals of UHC and maximizing or ensuring healthy lives share a common aspiration that could reasonably be translated into “healthcare for all” and “health for all.” Healthcare and health for all is undeniably analogous to the right to health imperative to ensure everyone’s access to the highest attainable standard of health, including healthcare and health determinants like water, food, and sanitation. Certainly the reports are replete with references to human rights, and this language appears to be infiltrating into the substance of proposals as well as the participatory process used to influence deliberations.

Yet the four reports examined in this paper are highly variable in how they address the right to health, and where this right is conspicuously absent in the HLP report, there is a far more limited ambition with regard to health. This finding suggests that express use of right to health language ‘frames’ policy responses by implicitly guiding actors toward a universalistic impetus in health and healthcare. Certainly we acknowledge the potential limits in causality between the use of right to health discourse and the formulation of UHC targets: those inclined towards UHC might already be inclined towards a normatively synergistic right like health, and vice versa, the choice of right to health-oriented language may reflect a pre-existing elective affinity towards universalistic measures.49 Nonetheless, the implication is that the right to health and UHC may offer impetus towards equity that non-rights-based, non-universal goals may not, and more specifically, that UHC rooted in right to health may offer polycentric gains towards equity with implications for action in a range of spheres including health financing.

We recognize the limitations of this finding given this study’s small sample size, and that more robust findings may become possible as the final SDG document is disseminated. Moreover, we acknowledge that our hypothesis may have limited impact on the SDG themselves which will likely be finalized before publication of this comment. Nonetheless, our analysis may have continuing relevance to the formulation of SDG targets and indicators, unlikely to be completed before March 2016.50 In addition, we believe that the primary relevance of this analysis will be to guide future global health policy negotiations through two primary lessons learned: that express use of right to health language may subtly guide actors in the direction of realizing this right, and that participatory processes allied with social advocacy are key variables in pushing right to health frames into policy processes. These are findings worthy of more research, discussion, and implementation within the academic, civil society and policy communities invested in advancing global health.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for constructive and enriching feedback from anonymous reviewers. We are also grateful for excellent research assistance from Rebekah Sibbald. This work was supported by the University of Toronto Connaught Foundation New Researcher Award, the Canadian Institutes of Health Operating Grant – Priority Announcement: Ethics (grant EOG 131587); the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (grant health-F1-2012-305240); and the Australian Government’s NH & MRC-European Union Collaborative Research Grants (grant 1055138).

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No funders of this research have a proprietary or financial interest in the outcome of this research.

Authors’ contributions

LF conceptualized and wrote the first draft of this paper. GO and CB contributed to refining the conceptual approach of the paper and editing various drafts. All authors have approved the final version of the paper.

Authors’ affiliations

1Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. 2Department of Public Health, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. 3School of Public Health, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia.

Citation: Forman L, Ooms G, Brolan CE. Rights language in the sustainable development agenda: Has right to health discourse and norms shaped health goals? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(12):799–804. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.171

References

- 1. At high level event, UN officials call for human rights-backed development agenda. UN News Centre. June 9, 2014. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=47996#.U-p2jmO9YVA. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- 2. UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda. Realizing the Future We Want for All: Report to the Secretary-General. Geneva: United Nations; 2012. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Post_2015_UNTTreport.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Global update on the health sector response to HIV, 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progressreports/update2014/en/. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 4. Mann J, Gruskin S, Grodin MA, Annas GJ, eds. Health and Human Rights: A Reader. New York: Routledge; 1999.

- 5.Gruskin S, Mills EJ, Tarantola D. History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. Lancet. 2007;370(4):449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beyrer C, Pizer HF, eds. Public Health and Human Rights: Evidence-Based Approaches. Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2007.

- 7. United Nations (UN). “Millennium Declaration,” Resolution 55/2, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. Geveva: United Nations; 2000. http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 8.Alston P. Ships passing in the night: The current state of the human rights and development debate seen through the lens of the Millennium Development Goals. Hum Rts Q. 2005;27:755–829. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2005.0030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisor S. After the MDGs: citizen deliberation and the post-2015 development framework. Ethics Int Aff. 2012;26(1):113–133. doi: 10.1017/S0892679412000093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Langford M, Sumner A, Yamin AE. Introduction: situating the debate. In: Langford M, Sumner A, Yamin AE, eds. The Millennium Development Goals and Human Rights: Past, Present and Future. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013: 1-36.

- 11.Yamin AE, Boulanger VM. Why global goals and indicators matter: the experience of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the Millennium Development Goals. J Hum Dev Capab. 2014;15(2-3):218–231. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2014.896322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brolan CE, Hill PS. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the evolving post-2015 agenda: perspectives from key players from multilateral and related agencies in 2013. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(43):65–74. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. United Nations (UN). Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: United Nations; 1946. http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 14. United Nations (UN). Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III), U.N. Doc A/810 at 71 (1948). Geneva: United Nations; 1948. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 15. United Nations (UN). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 993 U.N.T.S. 3. Geneva: United Nations; 1966. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 16. United Nations (UN). International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 21 December 1965, 660 U.N.T.S. 195, 5 I.L.M. 352 1966. Geneva: United Nations; 1965. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=iv-2&chapter=4&lang=en. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 17. United Nations (UN). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, G.A. Res. 34/180, 34 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 46) at 193, U.N. Doc. A/34/46 (1979). Geneva: United Nations; 1979. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 18. United Nations (UN). Convention on the Rights of the Child, G.A. Res. 44/25, Annex, 44 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 49) at 167, U.N. Doc. A/44/49 (1989). Geneva: United Nations; 1990. http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 19. United Nations (UN). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, G.A. Res. 61/106, Annex I, U.N. GAOR, 61st Sess., Supp. No. 49, at 65, U.N. Doc. A/61/49 (2006). Geneva: United Nations; 2008. http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 20. The Right to Health: Fact Sheet No. 31. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and World Health Organization. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf. Updated 2008. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 21.Kinney ED, Clark BA. Provisions for Health and Health-Care in the Constitutions of the Countries of the World. Cornell International Law Journal. 2004;37:285–355. [Google Scholar]

- 22. United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, E/C.12/2000/4. Geneva: United Nations; 2000. http://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d0.html. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 23. Yamin AE, Gloppen S. Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health? Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 2011.

- 24.Hogerzeil HV, Samson M, Casanovas JV, Rahmani-Ocora L. Is access to essential medicines as part of the fulfillment of the right to health enforceable through the courts. Lancet. 2006;368(9532):305–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiffman J. A social explanation for the rise and fall of global health issues. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):565–644. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rushton S, Williams OD. Frames, paradigms and power: global health policy-making under neoliberalism. Global Soc. 2012;26(2):147–167. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2012.656266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan Z, Kosicki GM. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit Commun. 1993;10(1):55–75. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993.

- 29. Schon DA, Rein M. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies. New York: Basic Books; 1994.

- 30. Goffman E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of the Experience. New York: Harper Colophon; 1974.

- 31.Benford RD, Snow DA. Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Ann Rev Sociol. 2000;26:611–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rushton S, Williams OD. Frames, paradigms and power: global health policy-making under neoliberalism. Global Soc. 2012;26(2):147–167. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2012.656266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinlein T. Between myths and norms: constructivist constitutionalism and the potential of constitutional principles in international law. Nordic Journal of International Law. 2012;81(2):79–132. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finnemore M, Sikkink K. Taking stock: the constructivist research program in international relations and comparative politics. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2001;4:391–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. United Nations. Health in the Post-2015 Agenda: Report of the Global Thematic Consultation on Health. Geneva: United Nations; 2013. http://www.worldwewant2015.org/node/337378. Accessed August 12, 2014.

- 36. United Nations. A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development: Report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. New York: United Nations; 2013. http://www.post2015hlp.org/featured/high-level-panel-releases-recommendations-for-worlds-next-development-agenda/. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- 37. Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). An Action Agenda for Sustainable Development: Report for the UN Secretary-General. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions; 2013. http://unsdsn.org/resources/publications/an-action-agenda-for-sustainable-development/. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- 38. United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals, UN Doc. A/68/970. Geneva: United Nations; 2014. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/970&Lang=E. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- 39.Ooms G, Latif LA, Waris A. et al. Is ‘universal health coverage’ the practical expression of the right to health? BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14(3):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stuckler D, Faigl AB, Basu S, McKee M. The political economy of universal health coverage. Paper presented at: Background paper for the Global Symposium on Health Systems Research; November 16-19, 2010; Montreux, Switzerland.

- 41.Schmidt H, Gostin LO, Emanuel EJ. Public health, universal health coverage, and Sustainable Development Goals: can they coexist? Lancet. 2015;386(9996):928–930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. United Nations General Assembly. Global health and foreign policy. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/67/L.36&referer=http://www.un.org/en/ga/info/draft/index.shtml&Lang=E. Accessed August 3, 2015. Published December 6, 2012.

- 43. World Health Organization (WHO). Positioning Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda, WHO Discussion Paper. Geneva: United Nations; 2012. http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/post2015/WHOdiscussionpaper_October2012.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 44.Sachs J. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):944–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Ruggiero E, Cohen JE, Cole DC, Forman L. Competing conceptualizations of decent work at the intersection of health, social and economic discourses. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. United Nations (UN). Health in the post-2015 development agenda: outline of proposed process for global thematic consultation on health. Geneva: United Nations; 2012. http://www.worldwewant2015.org/health. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- 47. Sustainable Development Solutions Network Thematic Group on Health. Health in the framework of sustainable development: Technical report for the post-2015 development agenda. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2014. http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Health-For-All-Report.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2015.

- 48. United Nations Open Working Group Technical Support Team. TST Issues Brief: Health and Sustainable Development. Geneva: United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/18300406tstissueshealth.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- 49. Mkwandawire T. Targeting and universalism in poverty reduction. In: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Social Policy and Development Programme Paper Number 23. Geneva: United Nations; 2005.

- 50. Orme B. The Sustainable Development Goals may be in place, but dissent was apparent. Pass Blue: Covering the UN. June 15, 2015. http://passblue.com/2015/06/14/the-sustainable-development-goals-may-be-in-place-but-dissent-was-apparent/. Accessed August 2, 2015.