Abstract

The challenge of mobilizing knowledge to improve patient care, population health and ensure effective use of resources is an enduring one in healthcare systems across the world. This commentary reflects on an earlier paper by Ferlie and colleagues that proposes the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm as a useful theoretical lens through which to study knowledge mobilization in healthcare. Specifically, the commentary considers 3 areas that need to be addressed in relation to the proposed application of RBV: the definition of competitive advantage in healthcare; the contribution of macro level theory to understanding knowledge mobilization in healthcare; and the need to embrace and align multiple theories at the micro, meso, and macro levels of implementation.

Keywords: Knowledge Mobilization, Resource-Based View (RBV), Implementation, Healthcare, Context

Addressing the translation of knowledge into policy and practice is a high priority within many healthcare organisations and systems, as the recent editorial by Ferlie and colleagues points out.1 However, it is a policy goal that remains complex and challenging despite the increased attention and investment that has been directed towards it in recent years. Take, for example, findings relating to the delivery of evidence-based clinical care at a population level. In their seminal research published in 1998, Schuster and colleagues concluded that 30% to 50% of care delivery in the United States was not in line with best available evidence.2 Applying similar methods to the earlier US study but around 15 years later, the CareTrack study in Australia reached an almost identical conclusion, namely that Australian patients received care judged to be in line with evidence-based guidelines only 57% of the time.3 Why is it so hard to move research-based knowledge into routine healthcare and what can be done about it?

Ferlie and colleagues1 suggest that in seeking solutions to this complex problem of knowledge mobilization in healthcare, we should be open to drawing on management theories, including theories that have their origins in the for-profit sector.Specifically, they highlight the relevance of the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, with its constituent elements of core competences, dynamic capabilities, absorptive capacity and organizational ambidexterity. Fundamentally, RBV is concerned with how an organization strategically deploys it resources – including the intangible resource of knowledge – to achieve competitive advantage.4 In considering the potential contribution of RBV to knowledge mobilization in healthcare, we focus our commentary on a number of key points, namely:

How we define ‘competitive advantage’ in healthcare;

The contribution of macro level theory to our understanding of knowledge mobilization;

The need to embrace and align theory across the micro, meso, and macro levels of implementation.

What Do Mean by ‘Competitive Advantage’ in Healthcare?

One of the common objections to importing private sector theories to inform thinking in healthcare is the view that healthcare organizations are fundamentally different as they are not subject to the same conditions or drivers as the private sector, namely a need to be profitable and to achieve competitive advantage over their rivals in order to survive. However, public sector healthcare organizations are universally subject to economic constraints and many are operating within market or quasi-market conditions as a result of various policy reforms. Whilst the relative advantage of introducing a market economy in healthcare is debated,5 one could conclude that there are enough similarities between the private and public sectors to suggest that theory transfer is relevant.6,7 Notwithstanding the likely transferability of RBV theory to healthcare, that still leaves us with the thorny issue of how we define competitive advantage. Is it about delivering the highest quality care at a population level? Or is it about providing the best possible experience of care at an individual patient level? Or alternatively, is it concerned with the efficient management of limited resources? Or indeed, all of these together – and if that is the case, is it feasible or possible to deliver on patient-centred, clinically effective and cost efficient healthcare simultaneously? Contemporary evidence from international health systems suggests it is very difficult to balance priorities such as individual patient experience, population health gain and cost containment, as the recent evaluation of the Triple Aim initiative instigated by the Institute for Health Improvement in the US demonstrates.8 Whilst a small number of the 141 participating organizations succeeded in the Triple Aim goals of improving individual experience of care, improving population health and reducing per capita costs, the majority were unable to pursue all 3 elements at the same time.

More worryingly, findings from investigations into major healthcare failures, such as the United Kingdom Francis Inquiry into Mid Staffordshire National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust highlight the harm that can be caused to patients if an organization becomes distracted or too intently focused on pursing some aims at the expense of others:

“the story [the inquiry] tells is first and foremost of appalling suffering of many patients. This was primarily caused by a serious failure on the part of a provider Trust Board.... This failure was in part the consequence of allowing a focus on reaching national access targets, achieving financial balance and seeking foundation trust status to be at the cost of delivering acceptable standards of care” (p. 6).9

One of the key recommendations of the Francis Inquiry was a need to focus on compassionate caring in health systems, a point reinforced by the current interest in understanding and promoting the fundamentals of patient care.10,11 An immediate challenge from an RBV perspective would be around how healthcare organizations can embrace patient-centred fundamental care as a strategic aim that aligns with their values, motivation and operational goals.12

Returning to our starting question of how we define competitive advantage in healthcare, it is clear that this is far from straightforward. Certainly it is concerned with maintaining and improving quality, but quality is a multidimensional concept and can mean different things to different people.13 This, in turn, has implications that need to be considered when we think about applying RBV to the study of knowledge mobilization of healthcare. First and foremost, we need to be clear about the knowledge we are aiming to mobilize and for what purpose – what is the advantage we are seeking to gain? In addressing this question, organizations need to think carefully about the different priorities that they need to deliver on and how to keep these in balance, with the patient and patient-centred care remaining centre stage throughout.

The Contribution of Macro Level Theory to Our Understanding of Knowledge Mobilization

A second consideration is the role that a macro level theory such as RBV can contribute to our understanding of effective knowledge mobilization in healthcare. Ferlie and colleagues1 make the point that many analyses of implementing evidence-based knowledge into healthcare practice have focused on barriers or obstacles at the micro level of individuals and teams. They argue that this needs to be complemented by attention at the macro system level to ensure that organizations have the core competences needed to support and facilitate effective and timely knowledge mobilization. From the experiences of knowledge mobilization in healthcare to date, what is the evidence to support this claim?

One source of evidence is the findings emerging from the first wave of Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in the English NHS. First established in 2008 with a mission to conduct and implement applied research in healthcare and to build capacity for knowledge mobilization within local health services, the CLAHRCs have been the focus of a number of external and internal evaluations.14-18 Whilst these evaluations demonstrate achievements in terms of mobilizing knowledge at the local project level, questions remain as to whether CLAHRCs in the organizational form of a knowledge mobilizing network deliver added value.17 This is due to the complex inter-relationship of a number of wider system-level factors such as the past history of partnership working amongst CLAHRC stakeholders, the influence of senior leaders and epistemic differences between partners in the network.14,16,19 This supports the need to draw on theory at a wider contextual level when planning, initiating and coordinating knowledge mobilization at an organizational or health system level. RBV and related theories of dynamic capabilities, absorptive capacity and organizational ambidexterity could provide useful insights to those involved in developing or evaluating knowledge mobilization at this wider system level.

Equally, researchers concerned with studying knowledge mobilization in healthcare more generally are increasingly recognizing the need to look at both internal and external contextual influences on implementation, as reflected in conceptual frameworks and models for knowledge mobilization.20,21 Again this adds support to the case for RBV as a useful theoretical contribution and – as Ferlie and colleagues highlight – we are beginning to see researchers drawing on this branch of strategic management literature to frame studies of knowledge mobilization and quality improvement in healthcare.22-24

The Need to Align Theory Across the Micro, Meso, and Macro Levels

Our final observation focuses on the need to adopt an eclectic yet aligned approach to knowledge mobilization in healthcare. Given the recognized complexity of knowledge mobilization and the influence of multiple factors relating to the evidence to be implemented, the context in which implementation takes place and the strategies and processes that are used to support implementation,25,26 there is potential for a range of different theories to be applied to guide knowledge mobilization efforts. This is an area that we have recently been studying as part of revisiting and revising the Promoting Action of Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Originally published as a conceptual framework in 1998,25 PARIHS proposed that successful implementation resulted from the interplay between evidence, context and the processes of facilitating implementation. The framework was subsequently tested and refined over the following 10 years26,27; more recently one of the issues that we have been focusing on is identifying the theories that underpin PARIHS as a conceptual framework. This, in turn, has led to a further revision of the framework to produce the integrated or i-PARIHS framework, which more explicitly integrates theories informing knowledge mobilization at a micro, meso, and macro level of implementation.21

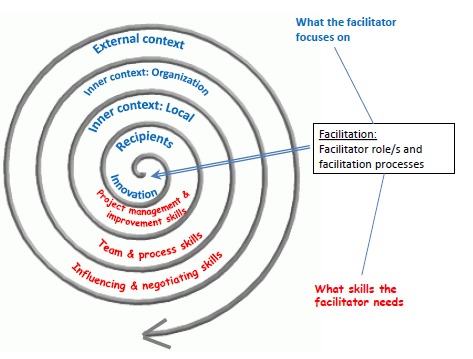

As a conceptual framework, i-PARIHS proposes that successful implementation results from the facilitation of an innovation with the recipients of the innovation in their local, organizational and health system context. Within the revised framework, evidence is incorporated within the broader concept of innovation to reflect the dynamic and iterative way in which knowledge to inform practice is generated and applied. Recipients at an individual and collective level are included as a new construct, acknowledging the central role of human agency in defining and shaping the process of mobilizing knowledge, and context is more clearly differentiated as spanning from a micro (local) level to meso and macro levels of implementation. Figure provides a visual representation of the i-PARIHS framework, illustrating the multiplicity of factors that influence knowledge mobilization. In order to assess and respond to these inter-related factors, i-PARIHS proposes that facilitation - comprising an individual (or individuals) in facilitator roles applying facilitation methods and processes – is essential as the active ingredient of implementation.

Figure 1.

The integrated-PARIHS Framework [Adapted From Reference 28].

Corresponding theories to inform thinking about the dimensions of innovation, recipients, levels of context and facilitation have been identified, as illustrated in table.

Table 1. Integrating Theories to Inform Implementation in the i-PARIHS Framework21 .

| Focus | Relevant Theories to Consider |

| Innovation | Evidence-based decision-making |

| Experiential, problem-based, and situated | |

| learning | |

| Diffusion of innovations | |

| Engaged scholarship | |

| Recipients | Diffusion of innovations |

| Readiness to change | |

| Theoretical domains framework | |

| Communities of practice | |

| Sticky knowledge and boundary theory | |

| Levels of context | Complexity/complex adaptive systems |

| Distributed leadership | |

| Organizational culture | |

| Learning organization | |

| Absorptive capacity | |

| Sustainability | |

| Facilitation role and process | Humanist/student-centred learning |

| Cooperative inquiry | |

| Quality improvement |

Abbreviation: i-PARIHS, integrated-PARIHS.Tiument alitae net quias

As the Table illustrates, absorptive capacity is specifically referenced as a theory that is relevant to understanding wider contextual influences; equally RBV as the parent theory would be pertinent to consider here. However, an important point to make is that in planning, conducting and evaluating knowledge mobilization, there are likely to be multiple theories that are appropriate and important to draw upon at any one time. This reflects the multifaceted and dynamic nature of knowledge mobilization in practice. It also suggests a need for a level of theoretical understanding and expertise amongst those who are responsible for leading or researching knowledge mobilization in healthcare. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that theories are applied that are consistent with underlying world-views about knowledge and knowledge mobilization. In the case of PARIHS and now i-PARIHS, we start from a position that knowledge mobilization is dynamic, iterative and multifaceted (as opposed to rational and linear), hence evidence has to be negotiated and adapted to context, which requires active facilitation by a facilitator employing enabling (as opposed to persuasive, coercive or telling) strategies. Consequently, the theories that we have listed as aligning with our beliefs about implementation and knowledge mobilization reflect the importance of situated, experiential learning, distributed leadership, humanistic approaches to learning and change and complex adaptive systems. We suggest that RBV and absorptive capacity theory is consistent with this worldview of knowledge mobilization as it acknowledges the contingent and dynamic way in which organizations seek, assimilate and apply knowledge to improve performance.23 However, it needs to be complemented by theories that more specifically focus on micro and meso level issues relating to the nature of the innovation, the key actors involved and their immediate work culture and organisational environment.

Conclusion

In this commentary we have reflected on the contribution of RBV theory to our understanding of knowledge mobilization in healthcare and come to the conclusion that it has a useful – but on its own – insufficient role to play. As a macro level theory, RBV could usefully align with more micro and meso level theories that recognise the multidimensional and contextually situated nature of knowledge mobilization. However, in adopting RBV, we suggest that a central concern has to be on articulating and debating what competitive advantage actually means in healthcare and, importantly, how healthcare organizations make sense of and manage the competing priorities that face them. Patients and patient-centred, compassionate care must feature at the heart of what healthcare organizations are attempting to achieve through effective knowledge mobilization.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors developed the ideas for this commentary. GH prepared the initial and the revised version of the paper. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Citation: Harvey G, Kitson A. Necessary but not sufficient: Comment on "Knowledge mobilization in healthcare organizations: a view from the resource-based view of the firm." Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(12):865–868. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.159

References

- 1.Ferlie E, Crilly T, Jashapara A, Trenholm S, Peckham A, Currie G. Knowledge mobilization in healthcare organizations: a view from the resource-based view of the firm. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(3):127–130. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuster M, McGlynn E, Brook R. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76:517–563. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runciman WB, Coiera EW, Day RO. et al. Towards the delivery of appropriate health care in Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;197(2):78–81. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barney J, Clark D. Resource Based Theory: Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- 5.Gilbert BJ, Clarke E, Leaver L. Morality and markets in the NHS. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(7):371–376. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walshe K, Harvey G, Hyde P, Pandit N. Organizational Failure and Turnaround: Lessons for Public Services from the For-Profit Sector. Public Money Management. 2004;24(4):201–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9302.2004.00421.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey G, Skelcher C, Spencer E, Jas P, Walshe K. Absorptive Capacity in a Non-Market Environment. Public Management Review. 2009;12(1):77–97. doi: 10.1080/14719030902817923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittington JW, Nolan K, Lewis N, Torres T. Pursuing the Triple Aim: The First 7 Years. Milbank Q. 2015;93(2):263–300. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Francis R. Report of the The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. Executive Summary. London: The Stationery Office;2103.

- 10.Kitson AL, Muntlin Athlin A, Conroy T. Anything but basic: Nursing’s challenge in meeting patients’ fundamental care needs. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(5):331–339. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne K. Duty to provide fundamentals of care spelled out in new NMC code. Nurs Stand. 2014;29(15):7. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.15.7.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitson A, Wiechula R, Conroy T, Muntlin Athlin A, Whitaker N. The Future Shape of the Nursing Workforce: A Synthesis of the Evidence of Factors that Impact on Quality Nursing Care. Adelaide, South Australia: School of Nursing, the University of Adelaide; 2013.

- 13.Swinglehurst D, Emmerich N, Maybin J, Park S, Quilligan S. Confronting the quality paradox: towards new characterisations of ‘quality’ in contemporary healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:240. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0851-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Andreta D, Scarbrough H, Evans S. The enactment of knowledge translation: a study of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care initiative within the English National Health Service. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(3 suppl):40–52. doi: 10.1177/1355819613499902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currie G, Lockett A, Enany NE. From what we know to what we do: lessons learned from the translational CLAHRC initiative in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(3 suppl):27–39. doi: 10.1177/1355819613500484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson J, Burton CR. et al. Collaborative action around implementation in Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care: towards a programme theory. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(3 suppl):13–26. doi: 10.1177/1355819613498859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald L, Harvey G. Translational networks in healthcare? Evidence on the design and initiation of organizational networks for knowledge mobilization. Soc Sci Med. 2015;138:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oborn E, Barrett M, Prince K, Racko G. Balancing exploration and exploitation in transferring research into practice: a comparison of five knowledge translation entity archetypes. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):104. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Currie G, El Enany N, Lockett A. Intra-professional dynamics in translational health research: The perspective of social scientists. Soc Sci Med. 2014;114(0):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harvey G, Kitson A. Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Healthcare: A facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015.

- 22.Burton CR, Rycroft-Malone J. Resource based view of the firm as a theoretical lens on the organisational consequences of quality improvement. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):113–115. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey G, Jas P, Walshe K. Analysing organisational context: case studies on the contribution of absorptive capacity theory to understanding inter-organisational variation in performance improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(1):48–55. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pablo AL, Reay T, Dewald JR, Casebeer AL. Identifying, Enabling and Managing Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector. J Manag Stud. 2007;44(5):687–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00675.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Quality Health Care. 1998;7:149–159. doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G. et al. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:174–180. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitson A, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARIHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges (2008) Implement Sci. 2008;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harvey G, Kitson A. A model of facilitation for evidence-based practice. In: Harvey G, Kitson A, eds. Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Healthcare: A Facilitation Guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015:47-69.