Abstract

Binagwaho and colleagues’ perspective piece provided a timely reflection on the experience of Rwanda in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and a proposal of 5 principles to carry forward in post-2015 health development. This commentary echoes their viewpoints and offers three lessons for health policy reforms consistent with these principles beyond 2015. Specifically, we argue that universal health coverage (UHC) is an integrated solution to advance the global health development agenda, and the three essential strategies drawn from Asian countries’ health reforms toward UHC are: (1) Public financing support and sequencing health insurance expansion by first extending health insurance to the extremely poor, vulnerable, and marginalized population are critical for achieving UHC; (2) Improved quality of delivered care ensures supply-side readiness and effective coverage; (3) Strategic purchasing and results-based financing creates incentives and accountability for positive changes. These strategies were discussed and illustrated with experience from China and other Asian economies.

Keywords: Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Sustainable Development, Asia, China, Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

After more than 3 years of deliberation and open discussions, the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be announced in September at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly this year. The SDGs will embrace a new mindset for global development focusing on inclusive and sustainable development. A commitment to health is reflected in the third SDG goal: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”1 Binagwaho and colleagues’ perspective piece2 provided a timely reflection on Rwanda’s experience in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and a proposal of 5 principles to carry forward in post-2015 health development.

This commentary echoes their viewpoints and discusses three strategies on designing and implementing health policy reforms consistent with these principles. These strategies were geared toward achieving the goal of universal health coverage (UHC), an integrated solution to advance the global health development agenda beyond 2015. UHC is the aspiration that everyone has access to quality healthcare when they need it, without incurring financial hardship. It is a simple idea, but one that has been recognized as “the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer” by the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Margaret Chan, and “the third global health transition” by the Rockefeller Foundation President Judith Rodin. Major international development partners including the World Bank and the WHO are urging and assisting countries to pursue UHC-related reforms. As the Ebola crisis had painfully showed, lack of access to quality essential health services undermines individual health security, which in turn, poses a threat to our collective health security.3 UHC is the vehicle to health system strengthening, in the effect that UHC improves equity in access to healthcare and financial protection, mobilizes more financial resources for health, ensures effective risk-pooling in the population, and galvanizes improvement in service delivery. Rwanda’s success in achieving MDG health goals greatly benefited from the quick expansion of health insurance coverage. Within the decade from 1999 to 2010, insurance coverage has exceeded 90%; utilization of health services increased from 0.2 in 1999 to 1.8 contacts per year in 20104; and incidence of catastrophic health spending among the insured households was almost four times less than households with no coverage.5 Rwanda’s success is due to strong political will and leadership in implementing many policy innovations.

Many Asian economies also made progress and generated useful lessons. For example, China, with a stellar economic performance that moved 600 million people out of poverty since the 1980s,6 made noteworthy progress in moving toward UHC by installing 3 major social health insurance schemes that covered more than 95% of the population now,7 and achieved some progress in utilization of health services and financial protection.8 Thailand achieved UHC in 2002. Its recent experience in strategic purchasing to ensure sustainability of UHC offers a policy lesson for other countries. Asian countries’ experience provided valuable insights on the complexity of reforms toward UHC and avoidable policy mistakes and detours.

Extending Health Insurance to the Poor

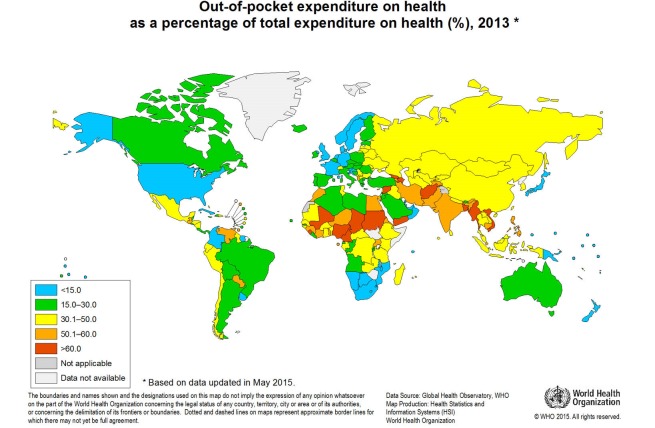

Expansion of health insurance coverage is often considered a major task of UHC. Health insurance protects individuals and households from financial catastrophe following healthcare by pooling financial resources and health risks among populations. Out-of-pocket (OOP) payment at the point of service, on the other hand, is the single most important cause of catastrophic health spending. WHO estimated that globally, about 150 million people suffer financial catastrophe annually, while 100 million are pushed into poverty. In 33 mostly low-income countries, direct OOP payments represented more than 50% of the total health expenditure in 2007; whereas only when direct payments fall to 15%-20% of total health expenditures, the incidence of financial catastrophe and impoverishment could fall to a negligible level.9 East Asia countries succeeded in bring OOP down to 30%-40%, whereas South Asia and Southeastern Asia countries still see OOP greater than 50% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Out-of-pocket (OOP) Expenditure on Health as a Percentage of Total Health Expenditure (%). Source: World Health Organization, 2015. http://gamapserver.who.int/mapLibrary/Files/Maps/OutPocketPercentageTotal_2013.png

Designing and implementing UHC is a technically complex, systematic effort. For the considerations of efficiency and equity, the global trend is towards bigger (or ideally, single) pool of resources by a single payer that provide equal level of coverage to all. Taiwan’s single payer system is efficient, using only 6.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) to provide all with a comprehensive benefit package and free choice of provider. Only 1.07% of expenditure spent on administrative overhead.10

While this is hard to achieve at once, country experience suggests that the sequencing of expanding health insurance is critical. Collecting funds from the formal sector is easier, but covering the formal sector first is inequitable as it tends to leave poorest people in the informal sector behind. Once separate pools are created and unequal benefits are prescribed for different schemes, it proves challenging to integrate them. For example, in China the establishment of three different social health insurance schemes whose funds are pooled at the county or municipal level led to a de facto of more than 300 different health insurance plans with better benefit packages for the urban employees.11 To improve equity, China is now struggling with integrating the different insurance schemes and unifying benefits. The lesson to be learned: a health insurance reform consistent with the SDG principles shall start with the extremely poor, vulnerable, and marginalized, create a financial protection floor for them, and gradually include other populations. This is exactly what Rwanda has done and achieved, even at a low-income level.2

Covering the poor requires governments increase public financing. In fact, many countries – Rwanda, China, or Vietnam and others – could not have achieved rapid expansion in health insurance coverage if not for massive public subsidies for insurance. The Chinese government provided 85% of the premiums of the New Cooperative Medical Insurance for rural residents and 60% of the premiums of the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance, on average.12,13 Vietnam financed its health insurance expansion with 70% of premium subsides from public financing.14 Rwanda has benefited from international aid, but in general, UHC requires more and sustainable domestically sourced financial resources. Though MDGs have been followed by major increases in global health financial inflow, the uncertain global economic prospect suggests a different trend post-2015. A recent report on global health financing by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA suggests that development assistance for health (DAH) increased at an average rate of 5.4% between 1990 and 2000 and 11.3% annually between 2000 and 2010, but it has plateaued since then and will remain flat or slightly drop in the coming years.15

Country governments must commit more domestic resources for UHC, most importantly domestic tax revenue, because the poorest in the country will always rely on the government to provide financial protection for basic health services. If African Union countries increased government expenditure on health to 15% as promised in the Abuja Declaration in 2001, they could together raise an extra US$29 billion per year for health.9 Promising approaches to gather more financial resources by the government include improving tax collection, introducing alternative tax structure and ear-marked tax for health and raising the priority of health development. A recent study on 89 low- and middle-income countries found that each US$100 per capita per year of additional tax revenue correspond to $10 yearly increase in government health spending, particularly for taxes on capital gains, profits, and income.16 Expanding the fiscal space for health financing and continuously fine-tuning the mix of financing is important even in high-income economies to sustain UHC. In Taiwan’s case, a 2% premium on 6 additional sources of non-payroll income (interest, dividend, rental income, bonuses, etc.) was added to the basic payroll-based premium base since January 2013. With this reform, the financial health of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) fund was turned from deficiency to surplus; in addition, the supplemental tax made the financing scheme more progressive by charging higher premiums for the well-to-do population.8

Improving Care Delivery for Effective Coverage

UHC does not equal universal insurance coverage. Effective coverage means that basic health services are available and accessible, delivered with high quality. This important dimension of UHC can be easily overlooked. In China and Vietnam, over-crowdedness at hospitals has been a prominent health system cost-driver. Patients bypass the primary care facilities to seek care at hospitals because patients lack trust to the quality of care at the primary care facilities, even though they may receive more prompt and cheaper services at these facilities. China devoted a large share of new government health fund to strengthen primary care infrastructure; however, without adequate health human resource, China risks wasted capital investment into primary health infrastructure and missed opportunity for better managed population health and prevention of diseases. Among all licensed physicians in China, only 4.5% are general practitioners (GPs), compared with 30%-60% in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.7,17 The acute shortage of GPs and over-demand for hospital specialists for common illness exacerbates the perception of lack of access to quality care. This affects disproportionately the poor and the rural population. Strengthening primary care requires re-defining the role of hospitals, and training, deploying and retaining primary care professionals according to the health needs of the population.

Scaling up the provision of quality supply of health services has been and will always be a great challenges in developing countries, which requires long-term investment in training, strong guidance and regulation, and right incentives to motivate health professionals. In addition, the lack of clinical standards and guidelines and loose management over clinical practice can be another barrier for improving standard care, often resulting in unsafe care. Recent studies in India18 and China19,20 using simulated patients or clinical audit method helped reveal the low level of conformity to recommended care and severe shortcoming of providers in grassroots facilities to prescribe accurate diagnosis and treatment for the most basic health problems. Though evidence remains scare, a recent meta-analysis found that the prevalence of healthcare-associated infection were much higher in developing countries than in developed countries. Surgical site infection was the leading infection in hospitals, and infection density in adult intensive care units was three times as high as those reported in the United States.21 Overuse of antibiotic drugs also contributes to antimicrobial resistance, a serious global health security threat.22

Introducing Incentives and Accountability

We consider strategic purchasing and results-based financing as important tools to introduce incentives and accountability to any UHC system. Strategic purchasing means that social insurance payers lever their financial power to proactively influence provider and patient behaviors for appropriate health management and treatment, and in turn, ensure the effective and efficient use of scarce financial resources. Result-based financing, used more frequently in the context of global development assistance, follows a similar philosophy – “paying for results.” A notable example from Asia is Thailand’s payment reform to establish a single payer that executes a set of strategic purchasing mechanisms to improve efficiency, equity, and accountability. As manager of the Universal Coverage Scheme, the National Health Security Office (NHSO) pays District Health System (DHS) networks using a population-based capitation formula to provide all outpatient (OP) services for their registered members. DHS also serves as a gatekeeper in the sense that it was liable for the cost of OP services if they refer patients out of the network, and patients bypassing without a referral are liable to pay OP services in full.23 In contrast, China’s experience suggests that strategic purchasing is not just desirable, but may be essential to keep cost of UHC affordable. Currently, the social health insurance fund is only mandated to balance revenue and expenditure in fund operations. Health services covered in the social health insurance benefit package were reimbursed regardless of their appropriateness and quality. As a result, it has contributed to incentives for over-prescription and over-treatment. The lack of effective cost control measures in the hospital sector led to the waste of billion dollars of public financing, and the Chinese government must adopt bold innovations in strategic purchasing to realign incentives and accountability of providers to high-value services.

The implementation of incentives and accountability system will require health systems to strengthen its own monitoring and evaluation function. The first step is clarifying the desired results and designing performance indicators, but more crucial is the routine monitoring of activities and progress towards results. To the end, it is important to seize the opportunity to lever advances in information technology to generate better evidence for policy-making and monitoring. Such evidence may be used to identify gaps and fine tune targets. For example, while the MDG goal on halving child mortality is achieved, evidence suggested that neonatal mortality now consists of over 60% of total child mortality. Logically, the next wave of efforts to reduce child mortality should focus on neonatal deaths. Evidences regarding the cost-effectiveness of interventions are crucial for the design of benefit packages, and such information need to be gather from clinical practice in the local circumstances. The post-2015 development agenda also calls for the launch of a data revolution by adopting a more comprehensive and sophisticated monitoring framework, and using “report cards” to measure progress towards sustainable development.24

Conclusions

UHC should be a central tenet for advancing the SDG health goals beyond 2015. As China and other Asian economies’ experiences showed, UHC is a technical complex, systematic reform process, but it would contribute to the economic and political sustainability of health development. As countries move forward with UHC reforms, they should particularly pay attention to equity in health insurance coverage, sustainable health financing, quality of care especially at the primary care level, and incentives and accountability for results.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YX prepared the manuscript. YX, CH, and UCR contributed to the collection of evidence.

Authors’ affiliations

1Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the World Bank Group, Boston, MA, USA. 2Milken School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Citation: Xu Y, Huang C, Colón-Ramos U. Moving toward universal health coverage (UHC) to achieve inclusive and sustainable health development: three essential strategies drawn from Asian experience: Comment on "Improving the world’s health through the post-2015 development agenda: perspectives from Rwanda." Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(12):869–872. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.156

References

- 1. Open Working Group proposal for Sustainable Development Goals. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgsproposal.

- 2.Binagwaho A, Scott KW. Improving the world’s health through the post-2015 development agenda: perspectives from Rwanda. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(4):203–205. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heymann DL, Chen L, Takemi K. et al. Global health security: the wider lessons from the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1884–1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makaka A, Breen S, Binagwaho A. Universal health coverage in Rwanda: a report of innovations to increase enrolment in community-based health insurance. Lancet. 2012;380:S7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60293-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saksena P, Antunes AF, Xu K, Musango L, Carrin G. Mutual health insurance in Rwanda: evidence on access to care and financial risk protection. Health Policy. 2011;99(3):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Bank. Poverty and Equity Country Dashboard. http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/country/CHN. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- 7. China Health and Family Planning Development Statistical Report. National Health and Family Planning Commission; 2014.

- 8.Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization (WHO). Health System Financing: the Path to Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cheng TM. Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance System. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(3):502–510. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Bank. Deepening health reform in China: building high quality and value-based service delivery. Unpublished.

- 12.Yip W, Hsiao WC. The Chinese health system at a crossroads. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):460–468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liang L, Langenbrunner JC. The long march to universal coverage: lessons from China. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/01/17207313/long-march-universal-coverage-lessons-china. Published 2013.

- 14.Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P. et al. “Health-financing reforms in southeast Asia: challenges in achieving universal coverage. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):863–873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Financing Global Health 2014: Shifts in Funding as the MDG Era Closes. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2014-shifts-funding-mdg-era-closes.

- 16.Reeves A, Gourtsoyannis Y, Basu S, McCoy D, McKee M, Stuckler D. Financing universal health coverage—effects of alternative tax structures on public health systems: cross-national modelling in 89 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):274–280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. OECD Health Statistics 2015. http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT. Accessed August 19, 2015.

- 18.Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(12):2774–2784. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Currie J, Lin W, Meng J. Addressing antibiotic abuse in China: An experimental audit study. J Dev Econ. 2014;110:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sylvia S, Shi Y, Xue H. et al. Survey using incognito standardized patients shows poor quality care in China’s rural clinics. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(3):322–333. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C. et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):228–241. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

- 23.Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W. et al. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals. http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/150612-FINAL-SDSN-Indicator-Report1.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2015.