Abstract

While FbpA, a family of bacterial fibronectin (FN) binding proteins has been studied in several gram-positive bacteria, the gram-negative Treponema denticola, an anaerobic periodontal pathogen, also has an overlooked fbp gene (tde1579). In this research, we confirm that recombinant Fbp protein (rFbp) of T. denticola binds human FN with a Kdapp of 1.5 × 10−7 M and blocks the binding of T. denticola to FN in a concentration-dependent manner to a level of 42%. The fbp gene was expressed in T. denticola. To reveal the roles of fbp in T. denticola pathogenesis, an fbp isogenic mutant was constructed. The fbp mutant had 51% reduced binding ability to human gingival fibroblasts (hGF). When hGF were challenged with T. denticola, the fbp mutant caused less cell morphology change, had 50% reduced cytotoxicity to hGF, and had less influence on the growth of hGF cells.

Keywords: Periodontal disease, Treponema denticola, Fbp, fibronectin binding protein, gene mutant

1. Introduction

Treponema denticola is a gram negative oral spirochete that has been associated with various forms of periodontal disease, including chronic periodontitis, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, endodontic infections, and some acute dental abscesses [1;2]. Virulence factors of T. denticola include motility and chemotaxis, production of tissue destructive enzymes, creation of cytotoxic products, and pathogen adherence to host tissue. Adhesion of pathogens to host tissues is critical in virulence strategies. T. denticola adheres to gingival fibroblasts [3] and epithelial cells [4], as well as extracellular matrix proteins [5]. T. denticola also adheres to other bacteria, such as Fusobacterium, which is important in biofilm formation [6;7].

Fibronectin (FN) is a multifunctional glycoprotein, which exists in the extracellular matrix, biological fluids, and on the surface of cells. Bacterial FN-binding proteins are recognized as virulence factors as it helps bacterial colonization and invasion [8]. For example, reducing the binding of S. aureus to FN attenuated the virulence [9], and deletion of the FN-binding protein gene sof2 in S. pyogenes resulted in a dramatic decrease in mouse mortality after intraperitoneal challenge [10]. FN is composed of three types of protein modules and has discrete binding sites for a variety of extracellular molecules [11]. FN also forms a molecular bridge between the bacterial surface and host cell integrin resulting in FN-mediated host cell bacterial invasion [12;13].

Fibronectin-binding by T. denticola was first described in 1990 [14]. Western blots have identified 53-kDa and 72-kDa surface antigenic proteins, as well as a 38-kDa axial flagellar protein in T. denticola that bound FN [15]. Recently, a novel family of FN-binding proteins with peptidoglycan binding domains were identified from T. denticola [16]. In T. denticola 35405, the major outer sheath protein was found to mediate the extracellular matrix binding activity [17]. This protein can bind both laminin and FN, but has no homology to the other bacterial FN-binding proteins [15;15;17;18].

The fibronectin-binding protein A (FbpA) family of genes contains at least 117 members from different bacterial species that have been annotated in the CDD database [19]. Few of those genes have been studied thus far, and it was shown that their gene products bound FN and correlated well with bacterial virulence. For example, isogenic mutants of fbpA in S. gordonii impaired binding to FN [20] and an isogenic pavA mutant in S. pneumoniae had 104 - fold attenuated virulence in a mouse sepsis model [21]. Analysis of the genome for T. denticola 35405 identified a gene (fbp, tde1579, GenBank: AAS12096.1) with significant homology to the FbpA family [22]. Fbp has two regions (22-136 and 171-293) that are homologous to the FbpA N-terminal segment. In T. denticola, the TDE1579 gene has been annotated, but its protein has been consistently overlooked in all previous work and has not been characterized.

In the present studies we hypothesize that the Fbp protein may contribute to the virulence of the gram negative bacterium T. denticola. To investigate the role of T. denticola's fibronectin binding protein (Fbp), we utilized molecular approaches. The phenotypes of our fbp mutant reveal novel functions of Fbp associated with the cytotoxicity of Treponema denticola.

2. Methods

2.1. Bacterial strains and DNA isolation

T. denticola ATCC 35405 was used as the source of genomic DNA and for other experiments in this research. The bacteria were maintained anaerobically (5% CO2, 10% H2, 85% N2) at 37 °C in GM-1 medium [3]. T. denticola ATCC 35405 chromosomal DNA was isolated using a detergent-proteinase K that includes treatment with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide to remove polysaccharides and cell wall debris [23].

2.2. Bioinformatics analysis of fbp gene

A conserved domain of FbpA was identified by sequence analysis with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [24]. Alignment of Fbp with other species of bacteria was performed by ClustalW with MegAlign in the DNAStar software [25].

2.3. Expression and purification of recombinant Fbp protein

The fbp gene was amplified by PCR with T. denticola ATCC 35405 genomic DNA as the template. The primers of rFbp Forward and rFbp Reverse (Table 1, P1 and P2) contained an XhoI or an EcoRI site for cloning into the expression vector pRSETA (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), which introduces a 39-residue tag (4.5 kDa) with His6 at the N-terminus of the recombinant protein to facilitate purification. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) by electroporation. The correct recombinant constructs (pFBP) were identified by colony PCR using the same primers and confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Nucleic Acids Core Facility in the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA). To purify the rFbp protein, 2L LB medium was inoculated with 2% of the overnight culture of recombinant E. coli, and grown at 37 °C for 4 hours when OD600 reaches 0.8. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added into the culture at 0.4 mM, and incubated for an additional 5 hour. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 30 ml 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0 with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and disrupted by sonication for 6 × 30 s using a Branson sonifier 450 with ½ inch disruptor horn (Branson Ultrasonics Corporation, Danbury, CT) at 160 watts. (40% of 400 watt maximum) The lysate was centrifuged at 35,000 g for 20 min and rFbp in the soluble fraction was then purified by nickel affinity chromatography using Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The bound rFbp was eluted by a step-gradient of imidazole (100, 150, 250 mM) in chromatography buffer on a Biological LP system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in the amounts of 65%, 30% and 5% respectively. The protein identities were verified by mass spectrometry at the UTHSCSA Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory.

Table 1.

Primers used in research

| Name | Description | Position in database | Sequence (5’ to 3’) including introduced restriction sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | rFbp Forward | 1627579-1627561 | XhoI ccgctcgagATGTCCTTAAACAATAAAG |

| P2 | rFbp Reverse | 1626135-1626152 | EcoRI cggaattcATGCAAAACCGTCAATGG |

| P3 | Fbp upstream Forward | 1628701-1628684 | EcoRI-XhoI cggaattctcgagCCGGCTGGCACGGGATGC |

| P4 | Fbp upstream Reverse | 1627484-1627501 | BamHI-SmaI cgggatcccgggGGCTGTATAAGAGGGCTG |

| P5 | Fbp downstream Forward | 1626366-1626349 | BamH1 cgggatccAGGCCGGAAACCTCGCAG |

| P6 | Fbp downstream Reverse | 1624990-1625007 | PstI aactgcagACCTGAAGGCGGAGGCCG |

| P7 | Upstream of crossover fragment Forward | 1628748-1628727 | GCGAACAGCCTTTTTAATGATG |

| P8 | ErmF Reverse | 205-180 | GCAGATGAGCAA ACATATAACCGAGG |

| P9 | Downstream of crossover fragment Reverse | 1624906-1624926 | GAAAGCGACTAAACAGCCTCG |

| P10 | ErmAM Forward | 2101-2126 | GTACCGTTACTTATGAGCAAG TATTG |

| P11 | Fbp Forward | 1627579-1627555 | ATGTCCTTAAACAATAAAGAAATAG |

| P12 | Fbp Reverse | 1626131-1626152 | AAAGATGCAAAACCGTCAATGG |

| P13 | Fbp internal deletion Forward | 1627437-1627418 | CTCTTGATGCCGGAGCATGC |

| P14 | Fbp internal deletion Reverse | 1626383-1626402 | GGGGATACTCTTCCCTGCCC |

| P15 | ErmF Forward | 675-699 | CGAAATTTCCTTTCAAAGTGGTGTC |

| P16 | ErmAM Reverse | 1889-1865 | TTGCTGAATCGAGACTTGAGTGTGC |

2.4. Binding between rFbp and human Fibronectin

We used plate-binding assays to analyze the interaction of Fbp with FN. rFbp was biotinylated by Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate, St. Louis, MO). 96-well plates were coated with 0.5 μg/well human FN (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Biotinylated rFbp was added at a concentration range (2.5 × 10−8 - 2 × 10−6 M) and was detected by alkaline phosphatase (AP) - conjugated streptavidin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate, St. Louis, MO) and quantified at 405 nm with an Opsys MR plate reader (Dynex, Chantilly, VA). Apparent Kd (Kdapp) values were calculated from binding curves using a nonlinear curve fitting algorithm (Sigma Plot, SPSS Corp, Chicago, IL).

Subsequently, we analyzed the interactions of rFbp with eight different recombinant FN fragments that were expressed in our laboratory. These covered the full length of human fibronectin. Briefly, the genes encoding these FN fragments were obtained by RT-PCR from human gingival fibroblast RNA, amplified by PCR and ligated into the expression vector pGYMX [26;27] with a N-terminal His tag. Recombinant proteins were purified by nickel affinity column from E. coli. Fig. 2D outlines the location of these FN fragments on a linear map of FN. We used plate-binding assays with biotinylated rFbp at 2 × 10−7 M to determine binding ability of FN fragments as described above.

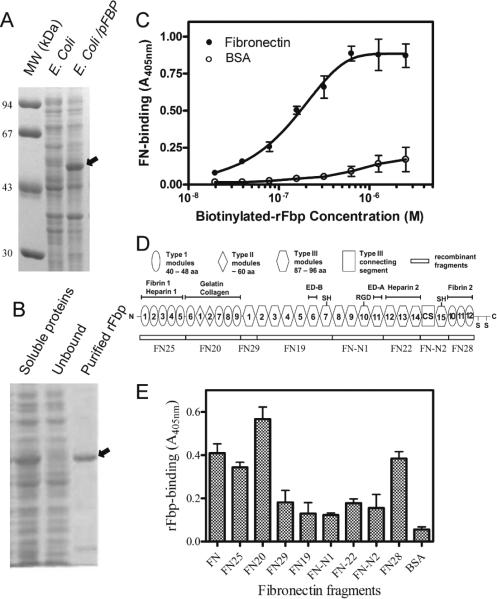

Fig. 2.

Recombinant Fbp binds to human FN in a concentration dependent manner, and preferentially binds type I and type II FN modules. A. SDS-PAGE shows expression of recombinant Fbp in E. coli/pFBP. B. The rFbp was purified from E. coli. (rFbp indicated by arrow). C. The purified rFbp binds FN in a concentration-dependent manner with Kdapp of 1.5 × 10−7 M. Each value is the average and SD of three independent assays. D. Eight recombinant FN fragments were illustrated as rectangular boxes with full length FN in a schematic diagram. E. The binding of rFbp to recombinant FN fragments was determined. Each value is the average and SD of three independent assays.

2.5. Interaction and competitive binding between T. denticola and human fibronectin

The 96-well plates were coated with human FN or ovalbumin at 1 μg/well in 0.1 M NaHCO3 / Na2CO3, pH 9.6 overnight at 4 °C and then blocked with 2.5% BSA. T. denticola cells were washed 3 times with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 by centrifugation and added at a concentration range (104 – 2 × 108 bacteria/well) to coated proteins for 1 h at 22 °C. The bound bacteria were incubated with mouse anti-T. denticola serum (1,000 × dilution), which was collected from mice that were immunized subcutaneously with 5 × 1010 T. denticola cells for 3 weeks, detected with an AP - conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and 1mg/ml PNPP substrate and quantified at 405 nm with an Opsys MR plate reader.

Competitive protein binding experiments were used to test the capacity of rFbp to compete interactions between T. denticola and FN. After coating plates with FN and blocking with BSA, T. denticola at 5 × 106 were added to the coated wells alone (control) or added simultaneously with a concentration range of competing rFbp or ovalbumin (2 – 0.015 μM). T. denticola bound to FN in the presence of rFbp was measured as described above. The capacity of rFbp to compete T. denticola binding to FN was expressed as a function of the concentration of the competing proteins.

2.6. Isolation of membrane and outer sheath fractions of T. denticola

About 7 × 1010 T. denticola cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 g, 10 min at 4 °C, suspended in 2 ml 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, containing complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and disrupted by sonication for 6 × 30 s using a Branson sonifier 450 with 1/8 inch micro tip at 160 watts. After removing unbroken bacteria by centrifugation, the lysates were then centrifuged at 100,000 g, 90 min, 4 °C to pellet membranes, leaving the supernatant as the soluble cytoplasmic fraction. The protein concentrations in both fractions were determined by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). To isolate outer sheath fraction by the freeze-thaw method [28], T. denticola ATCC35405 was suspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, containing complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and repeatedly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then thawed in a water bath at room temperature for 40 cycles. The suspension was then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min to remove cells, and the resulting supernatant was subsequently centrifuged at 100,000 g, 90 min at 4 °C. The pellet from the high speed centrifugation was suspended in Tris, pH 7.4 as the outer sheath fraction.

2.7. Anti-Fbp antiserum and affinity purification of antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against purified rFbp. In brief, rFbp eluted from the nickel column with 150 mM imidazole were pooled as the immunogen. Rabbits were injected subcutaneously bi-weekly with rFbp by Alpha Diagnostics International, San Antonio, TX, following a standard 63-day protocol. The titers of the antisera against coated rFbp in 96-well plate were determined by ELISA, which reached a titer of 105. Antibodies were first purified using a protein G chromatography according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The IgG fraction was further purified by rFbp affinity chromatography. Briefly, rFbp was conjugated to a cyanogen bromide-activated-Sepharose 4 fast flow resin (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) at 0.7 mg protein/ml resin. About 0.6 mg purified IgG containing anti-rFbp antibodies were loaded onto the column, washed with 0.5 M NaCl in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, eluted with 5 ml 100 mM glycine pH 2.4 buffer, and dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Purified antibodies were used in Western blot and immunogold labeling for electron microscopy analysis. We also made polyclonal antibodies against the T. denticola membrane fraction with the same protocol through Alpha Diagnostics International, San Antonio, TX.

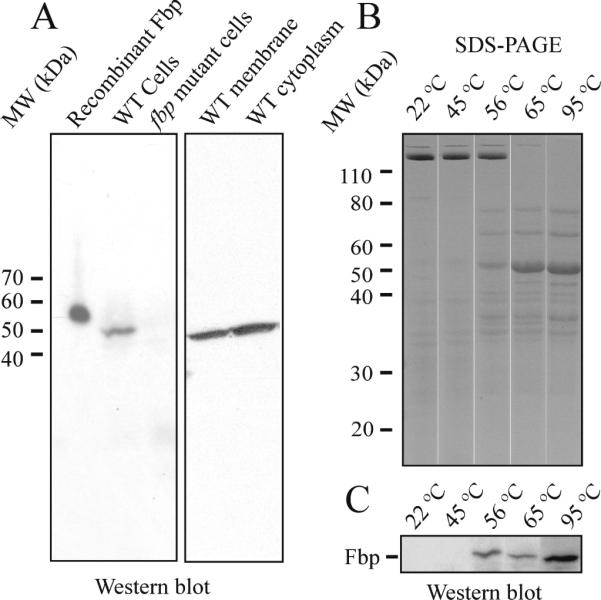

2.8. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of Fbp

A 12.6% acrylamide gel was used for SDS-PAGE. 4 ml of bacterial culture at 7 × 108/ml cells were pelleted by centrifugation and suspended in 100 μl 1 × SDS sample buffer containing 0.5 M urea, 0.5% SDS, 2.5 mg/ml DTT in 0.125 M Tris, pH 6.8. After heating at 95 °C for 5 min, 15 μl of suspended bacteria corresponding to 4.2 ×108 cells were loaded per well of the SDS-PAGE. T. denticola membrane and cytoplasmic fractions was quantified by BCA protein assays and loaded at 30 μg protein/well for Western blotting or at 10 μg protein/well for Coomassie blue R250 staining after heating at 95 °C or at indicated temperature for 5 min. rFbp was loaded at 10 ng protein/well as a positive control for Western blotting. For Western blotting, the PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-HCl saline buffer and then probed with the anti-rFbp antibodies described above at a 1:30 fold dilution. After washes, Fbp proteins were detected by using a horseradish-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with radiographic film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Novex Sharp Pre-stained Protein Standards (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) were used to estimate the molecular mass of Fbp.

2.9. Construction of fbp mutants of T. denticola

We used the established protocol (26) to construct fbp mutants in T. denticola. The plasmid pFBP::erm was first constructed by PCR approach, in which an 1117-bp internal region of fbp was replaced by an ermF-ermAM cassette in vector pUC18. Briefly, a 1218-bp DNA fragment, which includes the fbp upstream flanking region and the first 96-bp of fbp gene and a 1377-bp DNA fragment, which include the last 200-bp of fbp gene and the downstream flanking region were amplified by PCR using primers P3/P4 and P5/P6 (Table 1) respectively with T. denticola ATCC 35405 genomic DNA as template. BamH1 site at 3’ end of upstream fragment and 5’ end of downstream fragment were introduced for ligation. Both fragments were ligated into pUC18 and opened up with introduced SmaI site. An ermF-ermAM cassette was isolated as a PvuII fragment from plasmid P2198 (26) and ligated between upstream and downstream fragments to form plasmid pFBP::erm. The plasmid was linearized by introduced XhoI before electroporation into T. denticola. T. denticola competent cells were made by 24-hours culture at concentration about 2.5 × 1011/ml. Eighty μl of competent cells were mixed with 15 μg linearized plasmid pFBP::erm, and electroporation was carried out with an Eppendorf Multiporator at 1.8 kV in a 0.1 cm cuvette. After electroporation, the cells were incubated overnight in 2 ml GM-1 broth without erythromycin, then plated on TYGVS medium containing 0.85% sea plaque agarose with 40 μg/ml erythromycin and incubated in anaerobic chamber at 37 °C. The antibiotic resistant clones were characterized by PCR and confirmed by Western blot analysis.

2.10. Culture of human gingival fibroblast cells

Primary cultures of human gingival fibroblasts (hGF) were established from biopsies of gingiva according to the published methods [29;30]. Cells were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Mediatect, Herndon, VA) and Ham F-12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine calf serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100mg/ml streptomycin (Mediatect, VA) (DF10 medium) at 5% CO2 and 37 °C in the cell culture incubator. Cells between passages 10-16 were used for all experiments.

2.11. Binding of T. denticola to hGF

We used bacterial plate binding assays to compare the binding ability of wildtype and fbp mutants to hGF. The 3- day cultured hGF at 3 × 104 cells per well in a 96 well plate was interacted with a concentration range (7.8 × 105 – 2.5 × 107 /well) of bacteria in DF media without antibiotics for 2 hours. The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. The plates were washed with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween 20 and then blocked with 2.5% BSA overnight at 4 °C. Bound bacteria were detected by mouse anti-T. denticola serum (1,000 × dilution), AP - conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, 1mg/ml PNPP substrate and quantified at 405 nm with an Opsys MR plate reader.

2.12. Cytotoxicity of T. denticola to human gingival fibroblasts

To observe the cell morphology change, human gingival fibroblasts were cultured in 24-well plates for 3 days to near confluence in DF10 medium without antibiotics. Both wildtype and fbp mutant T. denticola were added to the cells at 5 ×108 cells/ml and incubated for an additional 48 hours. The morphological alterations of hGF cultures exposed to T. denticola were observed by phase contrast microscopy.

To determine hGF survival after being challenged with T. denticola, hGF cells were cultured in 24-well plates until confluent in DF10 medium without antibiotics, then T. denticola at appropriate concentrations were added to cell cultures and incubated for an additional 5 days. After rinsing 3 times with 1 ml PBS to remove detached human and bacterial cells and T. denticola, the viable fibroblasts were quantified by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) in 300 μl CellTiter-Glo reagent with a SpectraMAX Gemini XS plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

To determine the growth of hGF cells in the presence of T. denticola, hGF cells were passed to new 24-well plates at 104/well together with the appropriate concentration of T. denticola in DF10 medium without antibiotics. The cells and bacteria were co-cultured for 7 days. After washing, the viable fibroblasts were quantified by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay as described above.

3. Results

3.1. fbp gene in T. denticola is homologous to the members of bacterial FbpA family

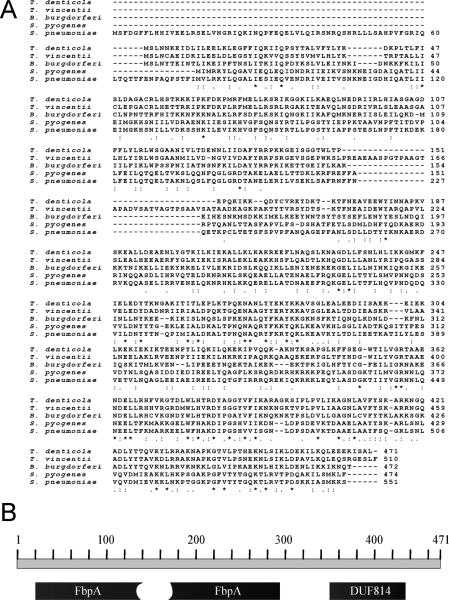

The gene tde1579 (Gene ID: 2739776) was annotated as a fibronectin/fibrinogen-binding protein (fbp) in T. denticola ATCC 35405 genome sequencing project [22]. The predicted protein (residues 22-293) has significant homology to other bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins that belong to the FbpA family (pfam 05833). The 1416 bp fbp gene of T. denticola theoretically encodes a 471 amino acid protein with a mass of 54,007 Da. Alignment of Fbp of T. denticola with FbpA of S. pyogenes (Fbp54) and S. pneumoniae (PavA) of gram-positive bacteria as well as FbpAs of two other spirochetes, T. vincentii (GenBank: EEV19639.1) and B. burgdorferi (BbuZS7_0351), were performed by ClustalW (Fig. 1A). The Fbp of T. denticola displays 20 % identity to PavA and 19% to Fbp54 which play a role in bacterial adhesion to target cells [21;31] and higher identity to FbpAs of other understudied spirochetes, B. burgdorferi (37%) and T. vincentii (60%). Fbp also contains a C-terminal domain (DUF814) with presently unknown functions (Fig. 1B). No conventional signal peptide was identified by the SignalP 4.1 Server [32] on fbp. In this research, the 1.4 kb fbp gene was amplified by PCR using T. denticola strain 35405 genomic DNA as template. The plasmid (pFBP) isolated from E. coli was verified to contain the complete fbp gene by DNA sequencing, which is identical to the fbp sequence in the database (accession number AE017226.1 in the genome database).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of fbp gene of T. denticola shows significant homology to other bacterial Fbp proteins in the FbpA family. A. Multiple alignment of FbpA proteins from T. denticola, T. vincentii, B. burgdorferi, S. pyogenes (Fbp54) and S. pneumoniae (PavA) by ClustalW. “*”; residues are identical in all sequences. “:”;conserved substitutions have been observed. “.”;semi-conserved substitutions are observed. B. Schematic diagram of identified domain structure of 471 residue Fbp protein. The FbpA domain is located in the N-terminal region with an internal deletion region. A domain of unknown function (DUF814) is located at C-terminal region.

3.2. Recombinant Fbp protein binds to human fibronectin type I and II modules

The rFbp protein was expressed in the soluble fraction of E. coli and visualized by SDS-PAGE. Denatured rFbp with its 4.5 kDa fusion tag migrated with a mass of 53 kDa in SDS-PAGE rather than the predicted molecular weight of 58.5 kDa (Fig. 2A). To determine whether expressed rFbp represented a truncated form of rFbp, the rFbp band was excised from the SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin, and further characterized by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. MS analysis identified peptides sequence coverage including both N- and C-terminal peptides of rFbp (data not shown). These results indicate that we expressed full-length rFbp in E. coli. Recombinant Fbp was purified to homogeneity from E. coli by nickel affinity chromatography. Unbound proteins passed through the column and purified rFbp was eluted by 150 mM imidazole (Fig. 2B). The total yield of rFbp determined after purification was about 3 mg/L bacterial culture.

In protein binding assays, rFbp bound immobilized human FN in a concentration–dependent manner (Fig. 2C) with an apparent Kd (Kdapp) at 1.5 ×10−7 M. To locate the Fbp binding sites on FN we tested rFbp binding with eight recombinant human FN fragments constructed and expressed in E. coli in our laboratory. These fragments covered the full length of the human FN molecule (Fig. 2D). Our results showed that rFbp preferentially binds to FN20, FN28 and FN25 (Fig. 2E). Among the three FN fragments, FN28 and FN25 contain type I modules whereas FN20, which had the strongest binding to rFbp, contains both type I and type II modules. In comparison, rFbp binding to module III-containing FN fragments such as FN29, FN19, FN-N1, FN22 and FN-N2 were relatively weak.

3.3. Recombinant Fbp protein inhibits binding of T. denticola to human FN

Binding of T. denticola to human FN has been reported previously [14;15]. In microwell plate assays, we confirmed T. denticola adhered to immobilized FN in a dose–dependent manner. To verify the specificity of the interaction, we demonstrated that rFbp could block the binding of T. denticola to FN in competition binding assays. The inhibition was concentration-dependent, reaching a maximum inhibition of 42%. Collectively these results demonstrate that Fbp has FN binding properties, and the interaction of rFbp with FN reduced the T. denticola binding to FN.

3.4. T. denticola 35405 expressed Fbp in both cytoplasmic and membrane fractions

To verify that the fbp encoded protein is present in T. denticola, we raised polyclonal anti-Fbp antibodies. Western blotting of T. denticola identified a 50 kDa Fbp protein band (Fig. 3A). The observed increase in mass of the recombinant Fbp over the native Fbp was attributed to the 4.5 kDa fusion tag. Western blotting demonstrated that Fbp protein was present in both the membrane and cytoplasmic fractions (Fig. 3A). We confirmed that Fbp were also presented in the outer sheath fraction of T. denticola which was isolated by the freeze-thaw method (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

A. Fbp was present in membrane and cytoplasmic fractions of wildtype T. denticola, but not in fbp mutant. B. T. denticola membrane treated at indicated temperature demonstrated that membrane proteins dissociated with heating. C. Fbp in T. denticola membrane was detected when T. denticola membrane was treated at temperature greater than 56 °C.

Some T. denticola membrane proteins, including the major outer sheath protein (Msp) [17] aggregate to form protein complexes that are dissociated upon heating. In Western blotting analyses, we detected the Fbp only when T. denticola membrane fractions were heat-treated before SDS-PAGE. Membrane fractions of T. denticola heated to different temperatures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, which showed that the major outer sheath protein (Msp) complexes dissociate at 65 °C (Fig. 3B). Western blotting analysis with the anti-rFbp antibodies detected monomeric Fbp only when samples were heated above 56 °C (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that Fbp may form a protein complex in the cell membrane which is dissociated by heating.

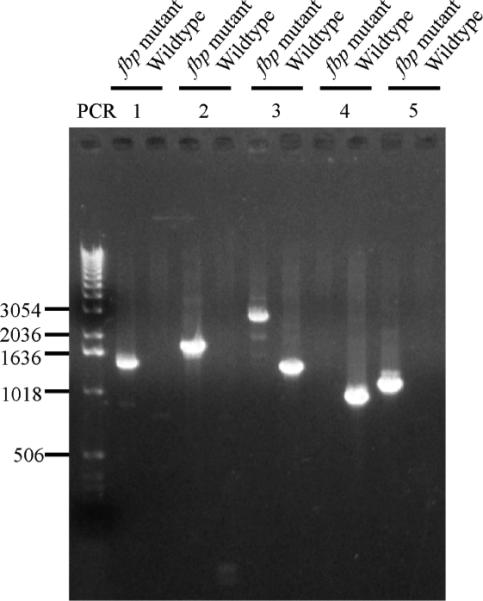

3.5. Construction and characterization of fbp deletion mutants of T. denticola

To determine the role of fbp, an isogenic deletion mutant of fbp was constructed. Twelve erythromycin–resistant colonies were obtained from 3 electroporations after 5 days of incubation. One mutant strain was characterized by PCR with different pairs of primers (Fig. 4). PCR 1 and PCR 2 showed that pFBP::erm construct was incorporated into the expected sites in the chromosome. PCR 3 with primers flanking fbp confirmed the presence of 1449-bp of fbp gene in wildtype strain and 2810-bp erythromycin inactivated fbp gene in the mutant strain. The PCR 4 with primers pair from deleted region of fbp amplified 1055-bp fbp in wildtype strain but not in mutant indicated the corresponding region of fbp have been deleted in mutant. The PCR 5 with primer from erythromycin cassettes confirmed the presence of erythromycin cassettes in the chromosome of mutant. PCR results indicated double crossover allelic exchange occurred in mutant as expected. To confirm the inactivation of fbp gene, the Fbp protein in the mutant was checked by Western blot, which indicated the Fbp protein was missing in fbp mutant (Fig. 3A, lane 3).

Fig. 4.

Confirmation of T. denticola fbp deletion mutant by PCR. Wildtype strain and fbp mutant with various primer pairs showed that fbp gene in T. denticola mutant was replaced by erm cassette.

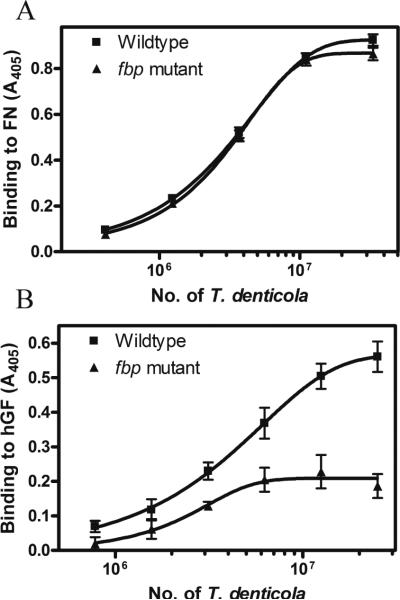

3.6. fbp mutants of T. denticola have deficiency in binding to human gingival fibroblast cells, but not to FN

In a bacterial plate binding assay, we find both wildtype and fbp mutant binds FN in a concentration dependent manner without significant difference (Fig. 5A). However, in bacterial binding to human gingival fibroblasts (hGF) assays, the wildtype bound to hGF in a concentration dependent manner. Meanwhile, the binding of the fbp mutant to hGF was reduced to 51% compared to wildtype (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

A. The binding of T. denticola to human FN and gingival fibroblast cells. No difference in bacterial FN binding between the wildtype strain and the fbp mutant was identified. Each value is the average and SD of three independent assays. B. The fbp mutant showed 51% reduced binding to hGF compared to wildtype. Each value is the average and SD of four independent assays.

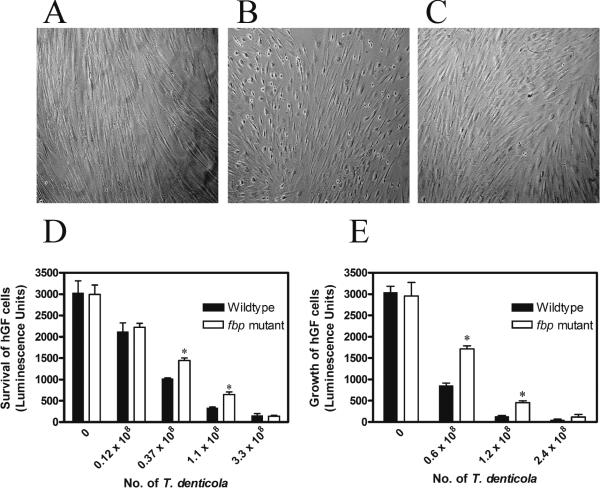

3.7. fbp mutants had reduced cytotoxicity to human gingival fibroblasts

To assess the cytotoxicity of our fbp deletion mutant, we challenged confluent human gingival fibroblast (hGF) cells with T. denticola. Untreated hGF cells had typical elongated spindle-shaped fibroblastic morphology (Fig 6A). After challenge with 5 × 108 wildtype T. denticola cells for 48 hours, we observed the hGF pseudopods were retracted and the cells became rounded. Eventually the hGF cells detached from the culture dishes (Fig. 6B). Given the same conditions, the fbp mutant caused significantly less morphologic changes (Fig. 6C), indicating the deletion mutant fbp had less virulence to cells. To quantify the cell death caused by T. denticola, viable hGF cells were quantified on day 7 after challenge. Results showed wildtype T. denticola caused more cell death at concentrations of 0.37 × 108 cells and 1.1 × 108 cells per well (Fig. 7D). To test if bacteria affect the growth rate of hGF cells, we added T. denticola to cell cultures immediately after passage of cells. After 7 days, 50% less viable hGF cells were present in the wildtype T. denticola co-culture than in the co-culture with the fbp mutant (Fig. 7E). This indicates the fbp isogenic deletion mutant has reduced virulence against hGF cell growth.

Fig. 6.

Cytotoxic effects of T. denticola on human gingival fibroblasts. The cultured hGF cells were challenged by T. denticola and were viewed by phase-contrast microscopy after 48 h. A. Unchallenged cells serve as negative control. B. hGF cells challenged with wildtype manifested a rounded shape. C. hGF cells challenged with fbp mutant showed less morphologic changes than those infected with wildtype. D. Survival of hGF cells were determined 5 days after challenge with T. denticola. The fbp mutant caused less cell death at concentration of 0.37 × 108 and 1.1 × 108 (*P <0.05 by one-tail t-test). Data is the average and SD of 3 independent experiments. E. The growth of hGF cells in co-culture with T. denticola after passage of cells on day 7 was determined. The fbp mutant had less effect on the growth of hGF cells than wildtype strain (*P <0.05 by one-tail t-test). Data is the average and SD of 3 independent experiments.

4. Discussion

Several bacterial proteins have been classified as a family of prokaryotic FN- binding proteins termed FbpA (FbpA, pfam05833 in Conserved Domain Database (CDD)) [20;21;31]. T. denticola was found to have a homologous fbp gene that belongs to the FbpA family [22]. Our experiments showed that rFbp binds immobilized FN with an apparent Kdapp at 1.5 ×10−7 M. This is similar to Fbp68 (2.5 ×10−7 M) [33]. No binding affinity constants have yet been reported for PavA, FbpA and Fbp54 [20;21;31]. The nature of the FN-binding motifs in bacteria is of particular structural interest. The N-terminal region corresponding to residues 1-89 was found to be responsible for the binding of FN in Fbp54 [31], while the 189 residue C-terminus was important for binding of FN in PavA [21]. However, no distinct FN-binding motif has been identified in the FbpA family, [21] although studies revealed manganese is needed for Fbp68 to bind FN [33]. In our experiments, Fbp preferentially bound type I and type II modules of FN. It was reported previously that heparin could reduce the binding of PavA to human FN by 60%, indicating that heparin binding domains are recognized by PavA [21]. It was also found that Fbp68 binds to the N-terminal domain of FN [33]. Of note, the N-terminal heparin binding domain of FN is composed of type I modules 1-5 and corresponds to our FN25 fragment that binds Fbp from T. denticola. The putative bacterial FN-binding motif FnBPs also binds to this region [34].

FbpA was proposed to play a role in bacterial adherence to FN or eukaryotic cells in gram-positive bacteria [20;21;35;36]. The cell surface exposure of Fbp was confirmed in PavA by immuno-electron microscopy [21]. Although we detected Fbp on the membrane fraction and outer sheath fraction of T. denticola, extraction of surface exposed protein with TritonX-114 did not pull out Fbp protein in T. denticola (data not shown). The sequence analysis did not identify a signal peptide either. This is unexpected in the general context of outer membrane proteins from T. denticola. For example, the major outer sheath protein (Msp) contains a 20-residue signal sequence with two positively charged amino acids after the first methionine and followed by a stretch of hydrophobic residues [17]. The mechanism for membrane localization of Fbp in T. denticola remains unknown.

Some outer membrane proteins form high molecular mass complexes on the surface of T. denticola. For example, the 53 kDa Msp is present in 130 kDa, 200 kDa and 300 kDa complexes that can be dissociated by heating above 70 °C [18]. In present studies, the 50 kDa monomeric form of Fbp was only detected when samples were heated above 56 C°, implying that Fbp may exist within a protein complex. It was reported that FbpA from L. monocytogenes is associated with two other proteins LLO and InlB [36].

It has been proposed that PavA functions at several stages in the infectious process. First, it may serve as an adhesin, mediating binding of bacteria to epithelial cells via FN. Second, the massive attenuation of virulence observed for pavA mutants in the mouse sepsis model points to a direct and critical role for PavA in virulence [21]. In order to study the function of Fbp in T. denticola, we constructed fbp mutants. Unfortunately the classic complementation experiment was unavailable due to the lack of a genetic complementation system in T. denticola 35405 [37;38]. To minimize potential polar effects on upstream and downstream genes, we limited the fbp deletion region. The deletion of wildtype fbp was carefully confirmed by a series of PCR experiments. Therefore, we expected that the phenotypic changes in the fbp-deletion mutants were attributed to fbp gene deletion.

Previous reports agree with our data; Fbp family proteins inhibit bacterial binding to human FN in a concentration dependent manner. We found rFbp inhibited the binding of T. denticola to human FN to a maximum level of 42%, while PavA inhibited 40% of the binding of S. pneumoniae to FN [21] and anti-Fbp68 inhibited 32% of the binding of C. difficile to FN [35]. These inhibitory effects may stem from rFbp filling available binding sites on FN for T. denticola, especially since the fbp mutant did not have any deficiency in FN-binding compared to the wildtype strain. It was found that T. denticola has several other FN-binding proteins including Msp, which also binds to type I modules 1-5 of FN [39]. Those proteins may be sufficient for the T. denticola binding to FN. Therefore, Fbp is not required when FN is the sole ligand for T. denticola binding. To further characterize the role of Fbp in bacterial adherence, we used gingival fibroblasts to test the binding ability of the fbp mutant. The reduction of binding of the fbp mutant to cells indicated Fbp plays a necessary role in the binding of T. denticola to cells. However, the specific ligands and Fbp's cellular binding mechanism need further investigation. Recently, it was found PavA-like Fbp in Enterococcus faecalis, EfbA plays a role for kidney tropism relative to the bladder, implying specific ligands may be present for EfbA [40].

FbpA may possess other virulent roles in addition to bacterial adherence. This was supported when we tested the bacteria against cultured hGF; the mutant demonstrated less virulence to cells. In future studies, we need to characterize the protein complex associated with Fbp in cell membrane and confirm if the Fbp protein is surface exposed. We also need to identify ligands of Fbp on the cell surface of human gingival fibroblast. In summary, the fbp gene and protein from a gram negative T. denticola was characterized. The isogenic fbp mutant has reduced cytotoxicity to human gingival fibroblasts. The mechanism of Fbp for those abnormal phenotypes need to be further characterized.

Fbp protein was identified in a gram-negative bacterium T. denticola

Recombinant Fbp protein in T. denticola binds fibronectin.

Isogenic mutant of fbp in T. denticola was constructed.

fbp mutant had reduced binding and cytotoxicity to human gingival fibroblasts.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Nucleic Acids Core Facility at the UTHSCSA for primers syntheses and DNA sequencing. We also thank Drs. Zhihua Chen and Sanjay Pal in Department of Periodontics, UTHSCSA for the expression and purification of recombinant fibronectin fragments, Dr. Susan Weintraub and Kevin Hakala at the UTHSCSA Mass Spectrometry Laboratory for mass spectrometry analysis and Barbara Hunter at Department of Pathology, UTHSCSA for electronmicroscopy observation. This work was supported by NIDCR grants DE021520, DE018135, DE017139, and DE014318 for COSTAR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sela MN. Role of Treponema denticola in periodontal diseases. Crit Rev.Oral Biol.Med. 2001;12:399–413. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dashper SG, Seers CA, Tan KH, Reynolds EC. Virulence factors of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. J.Dent.Res. 2011;90:691–703. doi: 10.1177/0022034510385242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberg A, Holt SC. Interaction of Treponema denticola TD-4, GM-1, and MS25 with human gingival fibroblasts. Infect.Immun. 1990;58:1720–1729. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1720-1729.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keulers RA, Maltha JC, Mikx FH, Wolters-Lutgerhorst JM. Attachment of Treponema denticola strains to monolayers of epithelial cells of different origin. Oral Microbiol.Immunol. 1993;8:84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haapasalo M, Hannam P, McBride BC, Uitto VJ. Hyaluronan, a possible ligand mediating Treponema denticola binding to periodontal tissue. Oral Microbiol.Immunol. 1996;11:156–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolenbrander PE, Ganeshkumar N, Cassels FJ, Hughes CV. Coaggregation: specific adherence among human oral plaque bacteria. FASEB J. 1993;7:406–413. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.5.8462782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grenier D. Demonstration of a bimodal coaggregation reaction between Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola. Oral Microbiol.Immunol. 1992;7:280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson B, Nair S, Pallas J, Williams MA. Fibronectin: a multidomain host adhesin targeted by bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins. FEMS Microbiol.Rev. 2011;35:147–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menzies BE. The role of fibronectin binding proteins in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Curr.Opin.Infect.Dis. 2003;16:225–229. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtney HS, Hasty DL, Li Y, Chiang HC, Thacker JL, Dale JB. Serum opacity factor is a major fibronectin-binding protein and a virulence determinant of M type 2 Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol.Microbiol. 1999;32:89–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pankov R, Yamada KM. Fibronectin at a glance. J.Cell Sci. 2002;115:3861–3863. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dziewanowska K, Patti JM, Deobald CF, Bayles KW, Trumble WR, Bohach GA. Fibronectin binding protein and host cell tyrosine kinase are required for internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by epithelial cells. Infect.Immun. 1999;67:4673–4678. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4673-4678.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozeri V, Rosenshine I, Mosher DF, Fassler R, Hanski E. Roles of integrins and fibronectin in the entry of Streptococcus pyogenes into cells via protein F1. Mol.Microbiol. 1998;30:625–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson JR, Ellen RP. Tip-oriented adherence of Treponema denticola to fibronectin. Infect.Immun. 1990;58:3924–3928. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3924-3928.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umemoto T, Nakatani Y, Nakamura Y, Namikawa I. Fibronectin-binding proteins of a human oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Microbiol.Immunol. 1993;37:75–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamford CV, Francescutti T, Cameron CE, Jenkinson HF, Dymock D. Characterization of a novel family of fibronectin-binding proteins with M23 peptidase domains from Treponema denticola. Mol.Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:369–383. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenno JC, Muller KH, McBride BC. Sequence analysis, expression, and binding activity of recombinant major outer sheath protein (Msp) of Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2489–2497. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2489-2497.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haapasalo M, Muller KH, Uitto VJ, Leung WK, McBride BC. Characterization, cloning, and binding properties of the major 53-kilodalton Treponema denticola surface antigen. Infect.Immun. 1992;60:2058–2065. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2058-2065.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Krylov D, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–D240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie J, McNab R, Jenkinson HF. Expression of fibronectin-binding protein FbpA modulates adhesion in Streptococcus gordonii. Microbiology. 2002;148:1615–1625. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes AR, McNab R, Millsap KW, Rohde M, Hammerschmidt S, Mawdsley JL, Jenkinson HF. The pavA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae encodes a fibronectin-binding protein that is essential for virulence. Mol.Microbiol. 2001;41:1395–1408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seshadri R, Myers GS, Tettelin H, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Dodson RJ, Davidsen TM, DeBoy RT, Fouts DE, Haft DH, Selengut J, Ren Q, Brinkac LM, Madupu R, Kolonay J, Durkin SA, Daugherty SC, Shetty J, Shvartsbeyn A, Gebregeorgis E, Geer K, Tsegaye G, Malek J, Ayodeji B, Shatsman S, McLeod MP, Smajs D, Howell JK, Pal S, Amin A, Vashisth P, McNeill TZ, Xiang Q, Sodergren E, Baca E, Weinstock GM, Norris SJ, Fraser CM, Paulsen IT. Comparison of the genome of the oral pathogen Treponema denticola with other spirochete genomes. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2004;101:5646–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307639101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Holt SC, Kolodrubetz D. Cloning and expression of two novel hemin binding protein genes from Treponema denticola. Infect.Immun. 2001;69:4465–4472. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4465-4472.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J.Mol.Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clewley JP, Arnold C. MEGALIGN. The multiple alignment module of LASERGENE. Methods Mol.Biol. 1997;70:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eltis LD, Iwagami SG, Smith M. Hyperexpression of a synthetic gene encoding a high potential iron sulfur protein. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1145–1150. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.9.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillemette JG, Matsushima-Hibiya Y, Atkinson T, Smith M. Expression in Escherichia coli of a synthetic gene coding for horse heart myoglobin. Protein Eng. 1991;4:585–592. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda K, Kawata T. Isolation, properties, and reassembly of outer sheath carrying a polygonal array from an oral treponeme. J.Bacteriol. 1982;150:1405–1413. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1405-1413.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oates TW, Mumford JH, Carnes DL, Cochran DL. Characterization of proliferation and cellular wound fill in periodontal cells using an in vitro wound model. J.Periodontol. 2001;72:324–330. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley CM, Wang Y, Pal S, Klebe RJ, Harkless LB, Xu X, Chen Z, Steffensen B. Fibronectin fragmentation is a feature of periodontal disease sites and diabetic foot and leg wounds and modifies cell behavior. J Periodontol. 2008;79:861–875. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courtney HS, Li Y, Dale JB, Hasty DL. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a fibronectin/fibrinogen-binding protein from group A streptococci. Infect.Immun. 1994;62:3937–3946. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3937-3946.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat.Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin YP, Kuo CJ, Koleci X, McDonough SP, Chang YF. Manganese binds to Clostridium difficile Fbp68 and is essential for fibronectin binding. J.Biol.Chem. 2011;286:3957–3969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz-Linek U, Hook M, Potts JR. Fibronectin-binding proteins of gram-positive cocci. Microbes.Infect. 2006;8:2291–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hennequin C, Janoir C, Barc MC, Collignon A, Karjalainen T. Identification and characterization of a fibronectin-binding protein from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology. 2003;149:2779–2787. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dramsi S, Bourdichon F, Cabanes D, Lecuit M, Fsihi H, Cossart P. FbpA, a novel multifunctional Listeria monocytogenes virulence factor. Mol.Microbiol. 2004;53:639–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chi B, Limberger RJ, Kuramitsu HK. Complementation of a Treponema denticola flgE mutant with a novel coumermycin A1-resistant T. denticola shuttle vector system. Infect.Immun. 2002;70:2233–2237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2233-2237.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abiko Y, Nagano K, Yoshida Y, Yoshimura F. Characterization of Treponema denticola mutants defective in the major antigenic proteins, Msp and TmpC. PLoS.One. 2014;9:e113565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edwards AM, Jenkinson HF, Woodward MJ, Dymock D. Binding properties and adhesion-mediating regions of the major sheath protein of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405. Infect.Immun. 2005;73:2891–2898. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2891-2898.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torelli R, Serror P, Bugli F, Paroni SF, Florio AR, Stringaro A, Colone M, De Carolis E, Martini C, Giard JC, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. The PavA-like fibronectin-binding protein of Enterococcus faecalis, EfbA, is important for virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. J.Infect.Dis. 2012;206:952–960. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]