Abstract

Background & Aims

Gastrointestinal (GI), liver, and pancreatic diseases are a source of substantial morbidity, mortality, and cost in the United States (US). Quantification and statistical analyses of the burden of these diseases are important for researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and public health professionals. We gathered data from national databases to estimate the burden and cost of GI and liver disease in the US.

Methods

We collected statistics on healthcare utilization in the ambulatory and inpatient setting along with data on cancers and mortality from 2007 through 2012. We included trends in utilization and charges. The most recent data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Cancer Institute.

Results

There were 7 million diagnoses of gastroesophageal reflux and almost 4 million diagnoses of hemorrhoids in the ambulatory setting in a year. Functional and motility disorders resulted in nearly 1 million emergency department visits in 2012; most of these visits were for constipation. GI hemorrhage was the most common diagnosis leading to hospitalization, with more than 500,000 discharges in 2012 at a cost of nearly $5 billion dollars. Hospitalizations and associated charges for inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile infection, and chronic liver disease have increased over the last 20 years. In 2011, there were more than 1 million people in the US living with colorectal cancer. The leading GI cause of death was colorectal cancer, followed by pancreatic and hepatobiliary neoplasms.

Conclusions

GI and liver diseases are a source of substantial burden and cost in the US.

Keywords: Abdominal pain, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, GERD, IBS, population

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) and liver diseases are highly prevalent, costly and lead to substantial health care utilization in the United States. Many of these diseases also affect patients’ quality of life and productivity.1 Given this burden of disease, the National Institutes of Health plans to devote an estimated $1.6 billion dollars to GI research and another $619 million dollars to liver disease research in 2015.2

Statistics quantifying the burden of GI and liver diseases are valuable in public health research, decision-making, priority-setting, and resource allocation. Reports describing the epidemiology of GI and liver diseases have been published and are commonly referenced for these reasons.1,3–8 We took advantage of recently available statistics to provide an update to our previous report.1

The objective of this work was to create a complete and accurate report detailing the current state of GI and liver morbidity, mortality, and cost in adults in the United States. We gathered data from several complementary national databases to achieve this objective.

Methods

We compiled the most recently available statistics from several publicly available databases. We utilized material available in the public domain or limited data sets with no direct patient identifiers. The methods used to collect the data from the source databases are detailed below.

Symptoms and Diagnoses across Ambulatory Settings

We tabulated the leading GI symptoms and diagnoses in the United States from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) for office-based outpatient visits and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) for emergency department and hospital-based outpatient visits for 2010. NAMCS and NHAMCS are annual national surveys sponsored by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide reliable information about the provision and use of ambulatory medical care services in the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm). The NAMCS collects data on visits to non-federal employed office-based physicians or non-physician clinicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NHAMCS collects data on visits to emergency department and hospital-based outpatient visits exclusive of Federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals.

To perform our analyses, we downloaded the public use data files from the CDC website. Both NAMCS and NHAMCS collect data on patient-reported symptoms. We used the patients’ most important complaint (variable RFV1) for the visit in our analyses. We combined related symptoms (Appendix 1) and we totaled and ranked data from office visits, emergency department and hospital outpatient departments. Physician and non-physician clinician diagnoses were categorized into relevant disease categories based on clinical expertise using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). We used the primary diagnosis code only. After combining the related diagnoses into clinically meaningful disease groups, we created a rank order list. NAMCS and NHAMCS are based on probability samples. Therefore, sampling weights were applied to all analyses in order to generate national estimates. These analyses were conducted using SAS v9.3 (Cary, NC).

Emergency Department Visits

We compiled the most common and selected other emergency department (ED) GI and liver principal visit discharge diagnoses from the 2012 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) (http://hcup.ahrq.gov/hcupnet.jsp). The NEDS was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NEDS includes discharge data for emergency department visits from 950 hospitals located in 30 States and is the largest all-payer database in the United States.

To perform our analyses, we utilized the ‘National Statistics on All ED Visits’ link on the HCUP website. We first created a list of the most common GI diagnoses in 2012. To do this, we queried the NEDS to generate a list of the top 100 principal diagnoses and then limited our list to GI and hepatology diagnoses only. We combined related diagnosis codes. We then performed a query for each individual ICD-9-CM code (or group of codes) to determine the total number of visits, number of visits per 100,000 people, the total number of patients admitted to the same hospital from the emergency department (ED) with that diagnosis and proportion of deaths either in the hospital or the ED. We also performed a temporal analysis to determine admission trends between the year 2006 (first year available in NEDS) and 2012. Finally, we created a list of select emergency department GI and liver principal discharge diagnoses that were not among the top 100 discharge diagnoses with methods similar to those detailed above.

Hospitalizations

The most common inpatient GI and hepatology discharge diagnoses were compiled from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), one of the databases in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (http://hcup.ahrq.gov/hcupnet.jsp). The 2012 NIS contains a 20 percent sample of discharges from 4,378 community hospitals participating in HCUP across 44 states. The sampling frame for the 2012 NIS comprises approximately 95 percent of the U.S. population, and includes more than 94 percent of discharges from U.S. community hospitals. The NIS is the only national hospital database containing hospital charges for all patients, regardless of payer, including persons covered by Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, and the uninsured.

To perform our analyses, we utilized the ‘National Statistics on All Stays’ link on the HCUP website. We queried the 2012 database for the top principal discharge diagnoses for all patients in all hospitals. From the top 100 diagnoses, we identified the GI and hepatology diagnoses and then rank-ordered then after combining related diagnosis codes. We then performed a separate query for each individual ICD-9-CM code (or group of codes) to acquire data on mean and median length of stay (LOS), median charges and costs, aggregate charges and aggregate costs, and number of inpatient deaths associated with each diagnosis or diagnosis group. We calculated the change in the number of admissions for the top principal GI diagnoses between the year 2003 and 2012 to identify relevant trends over the 10 year period. The total length of stay (LOS) was estimated by the product of the mean LOS and the number of discharges for each diagnosis. Total charges were converted to costs by HCUP using cost-to-charge ratios based on hospital accounting reports from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Cost data are presented rather than charges, as costs tend to reflect actual expenditures, while charges represent what the hospital billed for the case. In diagnosis categories represented by multiple ICD-9-CM codes, median LOS and median costs are presented for most common ICD-9-CM code in these categories. Rate of visits, admissions and deaths represent the sum from all codes. Total hospital days per year for all persons with each diagnosis were estimated from the product of the number of discharges and mean LOS.

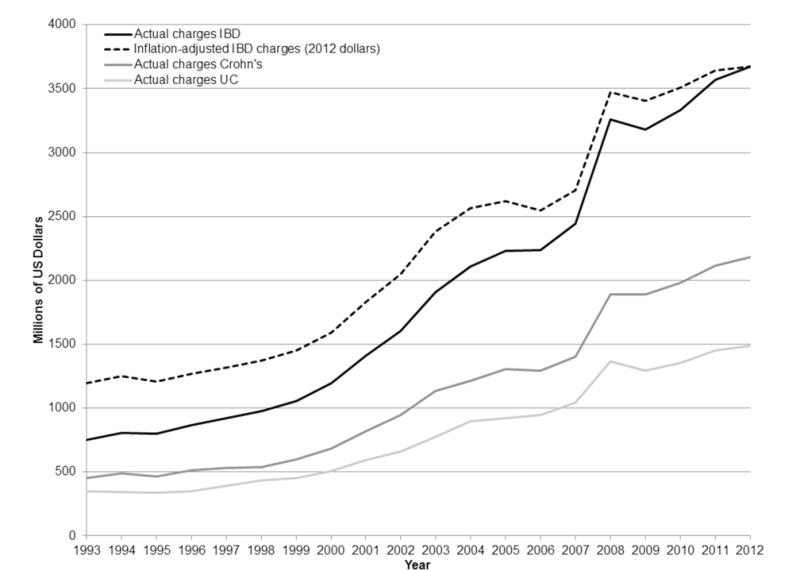

Finally, we reviewed the 10-year trend data and based on these numbers chose to perform temporal analyses for the number of admissions and associated costs for Clostridium difficile, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver disease between the year 1993 and 2012. For charge trends, we graphed the actual charges per calendar year, as well as inflation-adjusted charges (2012 dollars) using the Consumer Price Index published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov). Linear regression was used to determine statistical significance of trends over time.

Cancer

We collected GI and liver cancer statistics from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute (www.seer.cancer.gov).9 The SEER program collects and publishes cancer statistics from a collection of population-based cancer registries and represents approximately 28 percent of the United States population. We gathered the most recent version of the SEER estimates available from the SEER Cancer Statistics Review.9 Incidence rates were age adjusted and based on 2007–2011 cases. New cases were estimated for 2014. Prevalence was estimated for 2011. Lifetime risk was based on 2009–2011 data.

Mortality

We generated a list of the most common GI and liver causes of death using data from the Centers for Disease Control Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) (http://wonder.cdc.gov). CDC WONDER is a publically available database provided by the Centers for Disease Controls. The CDC maintains county-level, national mortality of children and adults collected and reported by state registries. Underlying and contributing causes of death are derived from death certificates and are classified by International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). The underlying cause of death is defined as the disease that initiated the sequence of morbid events leading directly to death. Contributing cause of death statistics include all deaths with the disease of interest as either the underlying cause or any of 20 additional diseases leading to death.

To perform our analyses, we downloaded the 2012 public use data files for underlying cause of death and multiple cause of death from the CDC website. Using ICD-10 codes, the 20 most common GI and liver causes of death were ranked. Diagnoses were combined to create clinically meaningful categories. The crude rate per 100,000 deaths was calculated by dividing the number of deaths listed as an underlying cause by the total U.S. population in the United States in 2012 (314,112,078 from the U.S. Census Bureau)10 then multiplying by 100,000. Results include children and adults. These analyses were conducted using Stata MP v13.0 (College Station, Texas).

Results

Symptoms and Diagnoses across Ambulatory Settings

The leading GI symptoms prompting a visit in 2010 are shown in Table 1. Abdominal pain was responsible for more than 27 million total visits, followed by diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and bleeding. Constipation and anorectal symptoms accounted for 3.0 and 2.6 million visits, respectively.

Table 1.

Leading Gastrointestinal Symptoms Prompting an Ambulatory Visit, 2010

| Rank | Symptom | Emergency Visits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office Visits | Emergency Department | Hospital Outpatient Department | Total | ||

| 1 | Abdominal pain | 15,028,011 | 10,416,899 | 1,655,073 | 27,099,983 |

| 2 | Diarrhea | 4,454,522 | 795,543 | 379,173 | 5,629,238 |

| 3 | Vomiting | 2,681,315 | 2,459,103 | 351,709 | 5,492,127 |

| 4 | Nausea | 2,343,409 | 2,187,272 | 184,238 | 4,714,919 |

| 5 | Bleeding | 2,691,658 | 672,402 | 279,969 | 3,644,029 |

| 6 | Constipation | 2,472,469 | 321,964 | 220,748 | 3,015,181 |

| 7 | Anorectal symptoms | 2,446,210 | 106,766 | 33,698 | 2,586,674 |

| 8 | Other GI symptoms, unspecified | 1,324,906 | 123,740 | 104,072 | 1,552,718 |

| 9 | Heartburn and indigestion | 1,355,288 | 81,831 | 23,515 | 1,460,634 |

| 10 | Changes in bowel function | 1,307,775 | 28,767 | 21,872 | 1,358,414 |

| 11 | Dysphagia | 808,250 | 118,465 | 115,399 | 1,042,114 |

| 12 | Decreased appetite | 837,473 | 114,282 | 52,136 | 1,003,891 |

| 13 | Flatulence | 582,303 | 4,817 | 1,706 | 588,826 |

| 14 | Abdominal distention | 373,732 | 98,256 | 57,828 | 529,816 |

| 15 | Symptoms related to the liver and biliary system | 411,063 | 28,449 | 83,755 | 523,267 |

Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm)

Abdominal pain is also the most frequent diagnosis (Table 2) with nearly 17 million annual visits. There were more than 7 million visits with GERD and reflux esophagitis. Hemorrhoids accounted for nearly 4 million visits.

Table 2.

Leading Diagnoses in the Ambulatory Setting for Gastrointestinal, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders in the United States, 2010

| Rank | Diagnosis | Estimated Visits | ICD-9-CM Codes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office Visits | Emergency Department | Hospital Outpatient Department | Total | |||

| 1 | Abdominal pain | 9,232,817 | 6,475,136 | 970,318 | 16,678,271 | 789.00 |

| 2 | Gastroesophageal reflux and reflux esophagitis | 6,222,275 | 294,942 | 549,992 | 7,067,209 | 530.11,530.81 |

| 3 | Hemorrhoids | 3,592,943 | 20,128 | 226,505 | 3,939,576 | 455 |

| 4 | Constipation | 2,905,705 | 530,827 | 280,129 | 3,716,661 | 564.0 |

| 5 | Nausea and vomiting | 1,404,564 | 1,969,949 | 215,701 | 3,590,214 | 787.0 |

| 6 | Abdominal wall and inguinal hernia | 2,852,677 | 204,375 | 422,937 | 3,479,989 | 550, 553.0, 553.1, 553.2, 553.9 |

| 7 | Malignant neoplasm of the colon or rectum | 2,420,463 | 2,420 | 386,783 | 2,809,666 | 153, 154 |

| 8 | Diverticular disease | 2,275,438 | 262,910 | 195,771 | 2,734,119 | 562.1 |

| 9 | Diarrhea | 1,943,572 | 533,181 | 197,071 | 2,673,824 | 787.91 |

| 10 | Gastritis and dyspepsia | 1,902,993 | 472,165 | 234,836 | 2,609,994 | 535, 536.8 |

| 11 | Irritable bowel syndrome | 2,290,460 | 24,121 | 89,170 | 2,403,751 | 564.1 |

| 12 | Crohn’s disease | 1,722,664 | 44,641 | 121,256 | 1,888,561 | 555 |

| 13 | Cholelithiasis | 872,040 | 355,504 | 119,166 | 1,346,710 | 574 |

| 14 | Dysphagia | 1,021,034 | 38,264 | 113,664 | 1,172,962 | 787.2 |

| 15 | Rectal bleeding | 648,827 | 176,160 | 61,772 | 886,759 | 569.3 |

| 16 | Benign neoplasm of colon and rectum | 726,675 | 144,775 | 871,450 | 211.3, 211.4 | |

| 17 | Pancreatitis | 409,862 | 320,418 | 91,492 | 821,772 | 577, 577.1 |

| 18 | Ulcerative colitis | 633,445 | 17,166 | 72,763 | 723,374 | 556 |

| 19 | Hepatitis C infection | 563,442 | 19,496 | 90,334 | 673,272 | 070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7 |

| 20 | Appendicitis | 317,374 | 195,150 | 128,524 | 641,048 | 540, 541, 542 |

| 21 | Hepatitis, unspecified | 554,749 | 3,212 | 9,573 | 567,534 | 573.3 |

| 22 | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 438,914 | 30,084 | 78,957 | 547,955 | 571 |

| 23 | Barrett’s esophagus | 369,739 | 47,083 | 416,822 | 530.85 | |

| 24 | Celiac disease | 23,521 | 4,472 | 27,993 | 579.0 | |

Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm)

Emergency department visits

The most common GI discharge diagnoses from the emergency department in the U.S. in 2012 as captured by the NEDS are detailed in Table 3. Abdominal pain was the most frequent visit diagnosis with an estimated 5.7 million visits. This diagnosis was rarely associated with admission to the hospital or death. GI hemorrhage was also a common discharge diagnosis almost 800,000 visits. More than half of these visits resulted in a hospital admission. Mortality from GI hemorrhage is substantial (10,393 deaths, 1.3% visits). Constipation was also common with nearly 800,000 visits and the number of ED visits for constipation has increased 60% since 2006.

Table 3.

| Most Common Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Principal Diagnoses From Emergency Department Visits, 2012

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Diagnosisa | Visits | Change from 2006 (%) | Rate of visits per 100,000 persons | Hospitalized from Emergency Department (%) | Death (%)a | ICD-9-CM Codes |

| 1 | Abdominal pain | 5,733,676 | +27 | 1,827 | 124,840 (2.2) | 834 (0.01) | 789.0, 789.6 |

| 2 | Nausea and vomiting | 1,937,744 | +35 | 617 | 36,755 (1.9) | 364 (0.02) | 787.0 |

| 3 | Noninfectious gastroenteritis/colitis | 1,200,159 | −24 | 382 | 118,863 (9.9) | 314 (0.03) | 558.9 |

| 4 | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 796,323 | +10 | 254 | 435,072 (54.6) | 10,393 (1.3) | 456.0, 456.20, 530.21, 530.7, 530.82, 531.0, 531.2, 531.4, 531.6, 532.0, 532.2, 532.4, 532.6, 533.0, 533.2, 533.4, 533.6, 534.0, 534.2, 534.4, 534.6, 535.01, 535.11, 535.21, 535.31, 535.41, 535.51, 535.61, 535.71, 537.83, 562.02, 562.03, 562.12, 562.13, 569.85, 569.86, 569.3, 578, 772.4 |

| 5 | Constipation | 799,614 | +61 | 255 | 50,587 (6.3) | 507 (0.06) | 564.00, 564.09, 560.32 |

| 6 | Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis | 651,829 | +31 | 208 | 309,436 (47.5) | 1,285 (0.20) | 574, 575.0 – 575.2 |

| 7 | Gastritis/duodenitis | 603,407 | +17 | 192 | 65,560 (10.9) | 99 (0.02) | 535.00, 535.10, 535.20, 535.30, 535.40, 535.50, 535.60, 535.70 |

| 8 | Diarrhea | 534,870 | +28 | 170 | 22,061 (4.1) | 161 (0.03) | 009.2, 009.3, 564.5, 787.91 |

| 9 | Gastrointestinal infectionb | 372,466 | +5 | 119 | 105,079 (28.2) | 240 (0.06) | 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 009, 008.00– 008.44, 008.46–008.8 |

| 10 | Appendicitis | 358,208 | +8 | 114 | 224,956 (62.8) | 164 (0.05) | 540–542 |

| 11 | Diverticulitis without hemorrhage | 333,464 | +31 | 106 | 157,562 (47.3) | 830 (0.3) | 562.11 |

| 12 | Acute pancreatitis | 330,561 | +12 | 105 | 239,839 (72.6) | 1,695 (0.5) | 577.0 |

| 13 | Gastroesophageal reflux | 324,359 | +4 | 103 | 43,296 (13.3) | 20 (0.01) | 530.81, 530.11, 787.1 |

| Selected Gastrointestinal and Liver Principal Diagnoses From Emergency Department Visits, 2012

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Visits | Change from 2006 (%) | Rate of visits per 100,000 persons | Hospitalized from Emergency Department (%) | Death (%)a | ICD-9-CM Codes |

| Functional/motility disordersb | 941,202 | +39 | 300 | 88,351 (9.4) | 377 (0.04) | 530.0, 530.5, 536.2, 536.3, 536.8, 536.9, 564, 306.4 |

| Liver disease and viral hepatitis | 288,678 | +24 | 92 | 187,938 (65.1) | 9501 (3.3) | 070, 570–573, 789.5, 789.59, 567.23, 456.1, 456.21 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 64,912 | −0.5 | 21 | 51,572 (79.5) | 2259 (3.5) | 571.0–571.3 |

| Hepatitis C | 33,237 | +176 | 11 | 26,906 (80.9) | 1046 (3.5) | 070.7,070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54 |

| Hepatitis B | 4,477 | +29 | 1 | 3,672 (82.0) | 149 (3.3) | 070.2, 070.3 |

| Ascites or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 48,346 | +87 | 15 | 12,215 (25.3) | 418 (0.9) | 789.5, 789.59, 567.23 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 50,446 | +18 | 16 | 43,065 (85.4) | 2569 (5.09) | 572.2 |

| GI disorders during pregnancyc | 254,190 | +19 | 81 | 13,357 (5.3) | – | 643, 646.7 |

| Upper GI bleedingd,e | 226,580 | −5 | 72 | 180,767 (79.8) | 3,739 (1.7) | 456.0, 456.20, 530.21,530.7, 530.82, 531.0, 531.2, 531.4, 531.6, 532.0, 532.2, 532.4, 532.6, 533.0, 533.2, 533.4, 533.6, 534.0, 534.2, 534.4, 534.6, 535.01, 535.11, 535.21, 535.31, 535.41, 535.51, 535.61, 535.71, 537.83, 569.86, 578.0 |

| Lower GI bleedinge | 342,102 | +17 | 109 | 13 7,288 (40.1) | 2,086 (0.6) | 562.02, 562.03, 562.12, 562.13, 569.85, 569.3, 578.1 |

| Foreign body in intestinal tract | 184,503 | +18 | 59 | 11,703 (6.3) | 45 (0.02) | 935.1–938 |

| C. difficile infection | 118,834 | +51 | 38 | 103,773 (87.3) | 2321 (2.0) | 008.45 |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | 125,755 | +38 | 40 | 71,609 (56.9) | 186 (0.2) | 555, 556 |

| Crohn’s disease | 86,652 | +38 | 28 | 45,881 (52.9) | 28 (0.03) | 555 |

| Ulcerative Colitis | 39,103 | +40 | 13 | 25,728 (65.8) | 146 (0.4) | 556 |

| Dysphagia | 71,042 | +18 | 23 | 8,353 (11.8) | 105 (0.2) | 787.2 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 35,695 | +2 | 11 | 10,609 (29.7) | 39 (0.1) | 787.2 |

| Eating Disorders | 4,564 | +14 | 2 | 1,421 (13.1) | – | 307.51, 307.1, 307.50, 307.59 |

Includes deaths in ED and in hospital deaths for patients admitted from ED with corresponding diagnoses

Does not include Clostridium difficile infections

Source: HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp)

Includes deaths in ED and in hospital deaths for patients admitted from ED with corresponding diagnoses

Includes esophageal (e.g. achalasia), gastric (e.g. dyspepsia), and intestinal (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome) functional/motility syndromes. Also includes some constipation and diarrhea codes from Table 3

Too few deaths to generate an estimate

Does not include codes for bleeding varices, which are included in the “gastrointestinal hemorrhage” category.

Does not include “Gastrointestinal hemorrhage NOS (578.9). Upper and lower GI bleeding are subcategories of “gastrointestinal hemorrhage” category.

Source: HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp)

Select GI and liver discharge diagnoses are detailed in Table 3. Functional and motility disorders had close to a million visits and increased by 39% since 2006. The majority of these visits were for constipation, as per Table 3. ED visits for liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease have both increased since 2006, and both disorders result in hospital admission in a majority of cases.

Hospitalizations

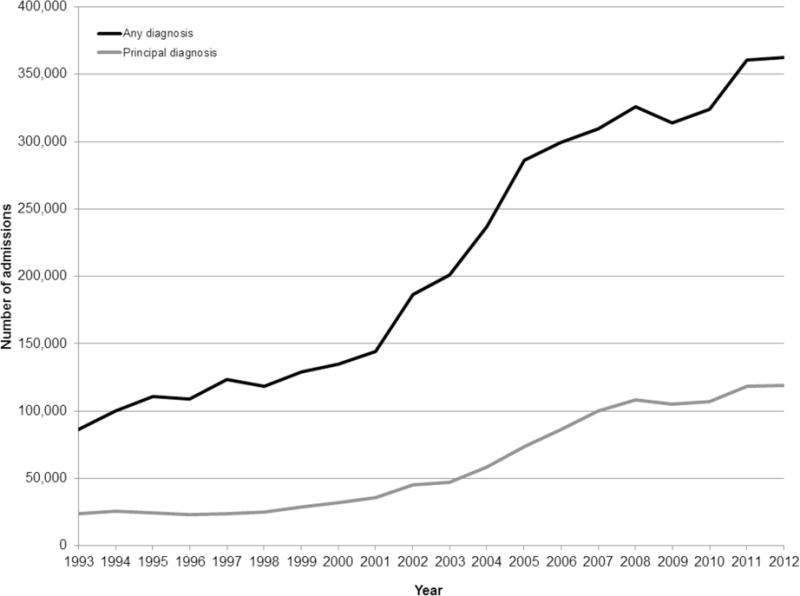

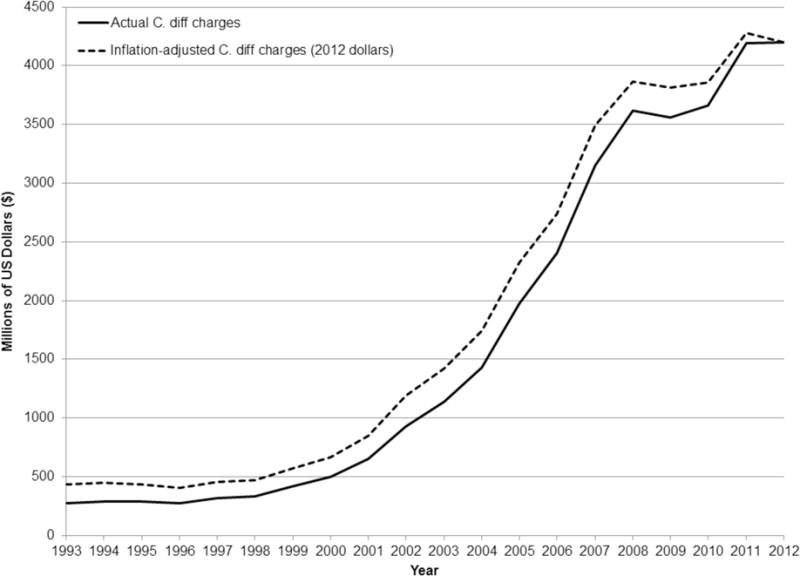

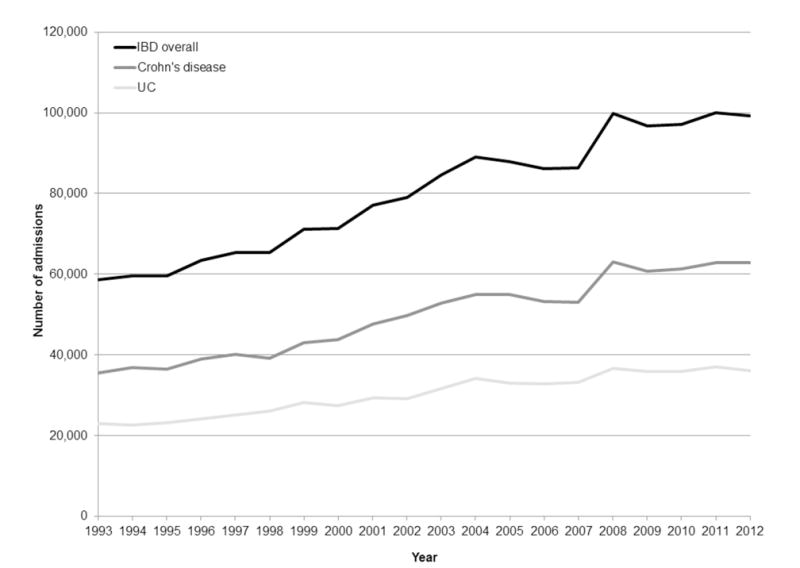

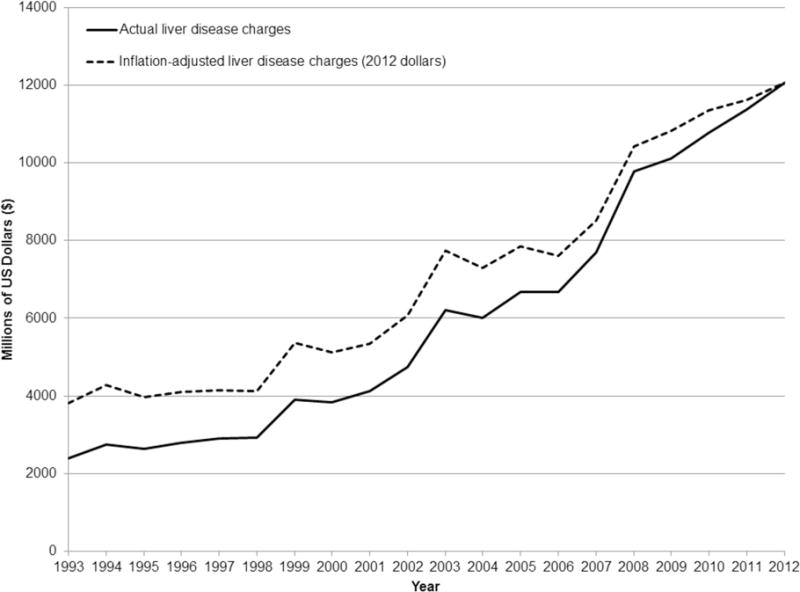

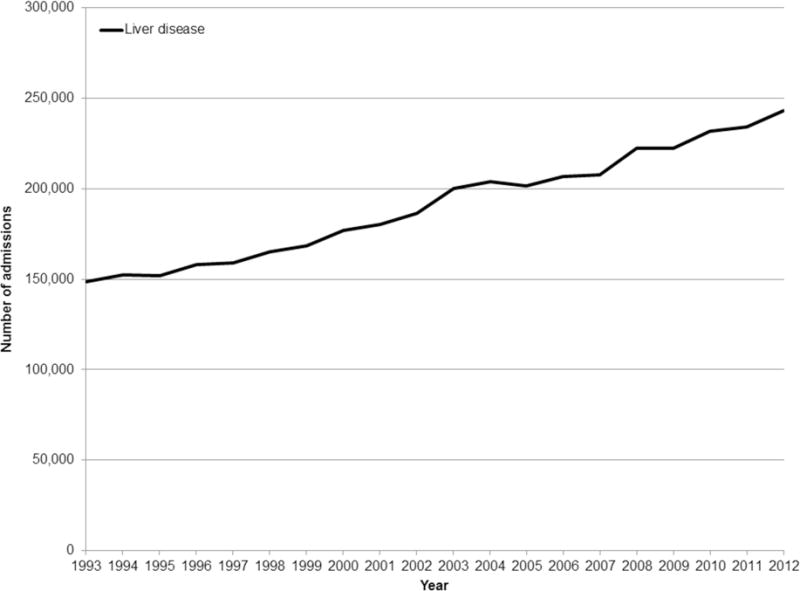

The most common GI and liver discharge diagnoses from hospital admissions are detailed in Table 4. GI hemorrhage was the most frequent discharge diagnosis with more than 500,000 discharges in 2012 at a cost of nearly $5 billion dollars. Hospitalizations for Clostridium difficile infection and associated charges continue to increase as illustrated in Figure 1A and Figure 1B. Regardless of inflation, the increases in spending are statistically significant (p<0.0001). There are higher aggregate costs for chronic GI conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, motility disorders, and chronic liver disease, despite fewer number of total hospital days. Hospitalizations and charges for inflammatory bowel disease and chronic liver disease in particular have increased over the last twenty years as seen in Figures 1C–F. These increases in spending are also statistically significant, regardless of inflation (p<0.0001). These charges are also detailed in table format in Appendix 2. Chronic liver disease had the highest inpatient mortality (5.8%, with roughly 14,000 annual hospital deaths).

Table 4.

Most Common Gastrointestinal, Liver and Pancreatic Principal Diagnoses From Hospital Admissions, 2012

| Rank | Diagnosis | Admissions | Change from 2003 (%) | Median Length of Stay (days) | Total Hospital Days | Median Costs (US dollars) | Aggregate Costs (US dollars) | In Hospital Death (%) | ICD-9-CM Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 507,440 | −1 | 3.0 | 2,131,248 | 6,700 | 4,853,663,600 | 11,065 (2.2) | 456.0, 456.20, 530.21, 530.7, 530.82, 531.0, 531.2, 531.4, 531.6, 532.0, 532.2, 532.4, 532.6, 533.0, 533.2, 533.4, 533.6, 534.0, 534.2, 534.4, 534.6, 535.01, 535.11, 535.21, 535.31, 535.41, 535.51, 535.61, 535.71, 537.83, 562.02, 562.03, 562.12, 562.13, 569.85, 569.86, 569.3, 578, 772.4 |

| 2 | Cholelithiasis with cholecystitis | 389,180 | −5 | 3.0 | 1,478,884 | 9,148 | 4,420,306,440 | 1,960 (0.5) | 574, 575.0–575.2 |

| 3 | Acute pancreatitis | 275,170 | +15 | 3.0 | 1,293,299 | 6,279 | 2,632,268,998 | 2,135 (0.8) | 577.0 |

| 4 | Intestinal obstruction | 256,775 | +38 | 3.0 | 1,463,618 | 5,237 | 2,919,447,015 | 267 (0.1) | 560.9, 560.89, 560.81 |

| 5 | Appendicitis | 248,080 | −13 | 1.0 | 694,624 | 7,287 | 2,405,135,600 | 270 (0.1) | 540–542 |

| 6 | Chronic liver disease and viral hepatitis | 243,170 | +21 | 5.7 | 1,386,069 | 49,611 | 3,314,650,270 | 13,990 (5.8) | 070, 570 – 573, 789.5, 567.23, 456.1, 456.21 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 61,670 | −4 | 5.9 | 363,853 | 50,316 | 848,147,510 | 3,140 (5.1) | 571.0–571.3 | |

| Hepatitis C | 34,360 | +225 | 5.4 | 185,544 | 54,629 | 493,821,920 | 1,660 (4.8) | 070.7, 070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54 |

|

| Hepatitis B | 4,600 | +31 | 5.3 | 24,380 | 50,210 | 61,506,600 | 220 (4.8) | 070.2, 070.3 | |

| Ascites or Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis | 15,675 | +172 | 5.2 | 81,510 | 38,223 | 173,052,000 | 550 (3.5) | 789.5, 789.59, 567.23 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 52,840 | +36 | 5.4 | 285,336 | 38,485 | 559,258,560 | 3,275 (6.2) | 572.2 | |

| 7 | Diverticulitis without hemorrhage | 216,560 | +21 | 4.0 | 2,181,992 | 6,333 | 2,178,031,586 | 1,005 (0.5) | 562.11 |

| 8 | Noninfectious gastroenteritis/colitis | 133,420 | −12 | 2.0 | 413,602 | 4,656 | 779,973,320 | 345 (0.3) | 558.9 |

| 9 | Obesity | 125,625 | +12 | 2.0 | 263,813 | 11,606 | 1,650,838,125 | 105 (0.08) | 278.00, 278.01 |

| 10 | Clostridium difficile infection | 119,315 | +151 | 5.0 | 715,890 | 6,871 | 1,170,881,881 | 2,630 (2.2) | 008.45 |

| 11 | Gastrointestinal infectiona | 117,450 | +11 | 2.0 | 364,095 | 4,070 | 685,203,300 | 245 (0.2) | 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 009, 008.00–008.44, 008.46–008.8 |

| 12 | Functional/motility disordersb | 115,975 | +17 | 3.8 | 440,705 | 25,739 | 844,877,875 | 395 (0.3) | 530.0, 530.5, 536.2, 536.3, 536.8, 536.9, 564, 306.4 |

| 13 | Inflammatory bowel diseases | 99,140 | +17 | 5.3 | 525,442 | 37,049 | 1,045,629,580 | 295 (0.3) | 555, 556 |

| Crohn’s disease | 62,965 | +19 | 5.0 | 314,825 | 34,676 | 627,698,085 | 105 (0.2) | 555 | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 36,175 | +14 | 5.7 | 206,198 | 41,186 | 417,965,950 | 190 (0.5) | 556 |

Does not include Clostridium difficile infections

Includes esophageal (e.g. achalasia), gastric (e.g. dyspepsia), and intestinal (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome) functional/motility syndromes.

Source: HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp)

FIGURE 1A.

Rising number of hospitalizations with associated or principal Clostridium difficile infection diagnoses

FIGURE 1B.

Rising charges for hospitalizations with principal Clostridium difficile infection diagnoses

FIGURE 1C.

Rising number of hospitalizations with principal diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

FIGURE 1F.

Rising charges for hospitalizations for principal diagnosis of liver disease

Some GI diagnoses were not among the “top 100” diagnoses overall, but do contribute to the burden of GI diseases. For example, chronic pancreatitis, with only 14,195 discharges, is very expensive (aggregate cost ~$150 million). Eating disorders, though an uncommon reason for hospitalization (n=5,865) are associated with long hospital stays (mean length of stay 12 days), high median charges ($51,847) and aggregate costs ($90,356,190).

Cancer

GI and liver cancer incidence, prevalence, and survival are detailed in Table 5. Using SEER data, the National Cancer Institute estimated that in 2011 there were more than a million people in the United States living with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. They also estimated 136,830 new cases of colorectal cancer each year with a 65% 5-year survival. The estimated lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer in the United States is 4.7%. Pancreatic, gastric and esophageal cancers remain common and highly lethal GI malignancies, all of which are associated with <30% 5-year survival.

Table 5.

Gastrointestinal, Liver and Pancreatic Cancer Statistics

| Cancer Site | Incidence Rate (new cases/100,000)a | New case estimate (per year)b | Prevalencec | Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer | % Surviving 5 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon and Rectum | 43.7 | 136,830 | 1,162,426 | 4.7% | 65% |

| Pancreas | 12.3 | 46,420 | 43,538 | 1.5% | 7% |

| Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Ducts | 7.9 | 33,190 | 45,942 | 0.9% | 17% |

| Stomach | 7.5 | 22,220 | 74,035 | 0.9% | 28% |

| Esophaguse | 4.4 | 18,170 | 34,551 | 0.5% | 18% |

| Small Intestine | 2.1 | 9,160 | – | 0.2% | 65% |

Age adjusted and based on 2007–2011 cases

Estimated for 2014

Estimated for 2011

Prevalence estimate not available

Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute (http://seer.cancer.gov)

Mortality

The leading causes of death from GI and liver disease are presented in Table 6. The top three causes of death from GI and liver disease remain colorectal cancer followed by pancreatic, liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers. All-cause cirrhosis contributed to 34,251 deaths in the U.S.. Clostridium difficile continues to be a source of substantial significant mortality, accounting for 7,739 deaths in the U.S. in 2012.

Table 6.

Causes of Death from Gastrointestinal, Liver and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States, 2012

| Rank | Cause of Death | Deaths (underlying cause) | Deaths (contributing cause) | Crude Rate (per 100,000) | ICD-10 Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Colorectal cancer | 51,139 | 58,816 | 16.6 | C18.0-21.0 |

| 2 | Pancreatic Cancer | 38,797 | 40,301 | 12.4 | C25.0-C25.9 |

| 3 | Malignant neoplasms of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts | 22,973 | 24,771 | 7.3 | C22.0-C22.9 |

| 4 | Hepatic Fibrosis/Cirrhosis (all-cause) | 17,495 | 34,251 | 5.6 | K74.0-K74.6 |

| 5 | Alcoholic Liver Disease | 17,419 | 22,851 | 5.5 | K70.0-K70.9 |

| 6 | Esophageal Cancer | 14,649 | 15,789 | 4.7 | C15.3-C15.9 |

| 7 | Gastric Cancer | 11,191 | 12,057 | 3.6 | C16.0-C16.9 |

| 8 | Vascular Disorders of the Intestine | 7,846 | 14,466 | 2.5 | K55.0-K55.9 |

| 9 | Clostridium difficile colitis | 7,739 | 12,050 | 2.5 | A04.7 |

| 10 | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, unspecified | 7,721 | 27,732 | 2.5 | K92.2 |

| 11 | Chronic hepatitis C | 7,292 | 17,788 | 2.3 | B18.2 |

| 12 | Paralytic ileus and intestinal obstruction | 6,074 | 15,592 | 1.9 | K56.0-K56.7 |

| 13 | Hepatic failure (acute and chronic) | 4,117 | 24,227 | 1.3 | K72.0-K72.9 |

| 14 | Ulcers (gastric/duodenal/peptic) | 2,892 | 5,850 | 0.9 | K25-K28 |

| 15 | Acute pancreatitis | 2,844 | 5,392 | 0.9 | K85.0-K85.9 |

| 16 | Diverticular disease | 2,773 | 4,567 | 0.9 | K57.0-K57.9 |

| 17 | Perforation of Intestine (non-traumatic) | 2,121 | 5,491 | 0.7 | K63.1 |

| 18 | Malignant neoplasms of gallbladder | 2,102 | 2,227 | 0.7 | C23 |

| 19 | Cholecystitis | 2,043 | 3,239 | 0.7 | K81.0-K81.9 |

| 20 | Fatty change of liver-not elsewhere specified | 1,241 | 2,593 | 0.4 | K76.0 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (http://wonder.cdc.gov)

Discussion

We have compiled the most recently available statistics from several complementary national databases to create a complete and accurate report detailing the current state of GI and liver morbidity, mortality, and cost in adults in the United States. GI and liver diseases account for substantial utilization of health care resources and cost in the United States. This report demonstrates several trends in the data worthy of highlighting.

The U.S population is growing older.11 This demographic is driven by the cohort of Americans born during the post-World War II baby boom (1945–1965). In 2011, the first baby boomers turned 65. This change in demographics is manifest in changes in liver disease in the U.S. Baby boomers are five times more likely to have chronic hepatitis C compared with adults born in other years.12 An estimated 2.7 million Americans have chronic HCV infection and most of those infected (75%) were born between 1945–1965.12–14 We found a 176% increase in hepatitis C related emergency department visits between 2006 and 2012 and a 225% increase in hepatitis C admissions between 2003 and 2012. In-hospital mortality was nearly 6%. Moreover, rates of new liver cancers are rising and many of these cancers are attributable to chronic hepatitis C infection.15, 16 The incidence of end stage liver disease from chronic hepatitis C infection is predicted to increase until the year 2030.17

Other GI diagnoses associated with age are also increasing. There are an increasing number of anorectal symptoms reported by patients and physicians in the ambulatory setting commonly diagnose hemorrhoids. Between 2006 and 2012, there has been an increase in the number of patients seen for constipation and lower GI bleeding in the emergency department. Hospital admissions for acute diverticulitis and C. difficile are increasing. By 2030, an estimated one in five Americans will be 65 or older. Even if the epidemiology of these conditions remains stable on an age-adjusted basis, we can expect increased numbers of cases and therefore increased utilization of health care and costs for these diseases.

The incidence of colorectal cancer and death rate from colorectal cancer in the United States continues to decrease and is in part attributable to screening and removal of adenomatous polyps.18–21 While this trend is encouraging, a substantial number of Americans are still diagnosed with and die from colorectal cancer every year. In 2014, an estimated 136,830 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer. In 2012, 51,139 people died from colorectal cancer. Despite the effectiveness of screening, in 2010 only 58% of adults aged 50 to 75 years had received colorectal cancer screening based on U.S. Preventative Services Task Force guidelines.22 A new initiative from the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable aims to increase colorectal screening in the United States to 80% by 2018, which would have the predicted benefit of preventing 280,000 cases of colorectal cancer and 200,000 deaths within 20 years.23, 24

Hospitalizations account for a large portion of the economic burden of IBD. Over the last twenty years in the United States, despite advances in therapy, hospital admissions and associated charges for inflammatory bowel diseases have increased. This is congruent with earlier trends using the National Hospital Discharge Survey.7, 25, 26 Emergency department visits are also rising.

This report has important strengths. We have gathered data from several complementary national databases each designed specifically to assess utilization. Since our last report1 we have obtained data from the NHAMCS. Adding NHAMCS provides a more comprehensive picture of GI symptoms and diagnoses in the ambulatory setting with more than a third of visits occurring in hospital-based clinics and emergency departments. We have also added statistics from the NEDS and for the first time present data for emergency department visits from two sources with different methods to assess visits. Despite differences in methodology, the estimates generated from these two sources appear to be similar, increasing our confidence in their accuracy.

There are important limitations imposed with the use of administrative data and ICD codes. The fidelity of coding data to clinical information is imperfect. Some trends may reflect coding changes occurring during the observed time period (e.g. codes for ascites changed in 2007). For most of our sources, data are coded by visit, and not by person, so a single patient could be represented by multiple visits or discharges. The methodology used in our data sources can change over time. For instance, the NIS utilized a new sampling strategy for the 2012 data. With this change, the estimated overall trends in discharge counts declined by about 4.3 percent, overall trends in average length-of-stay declined by about 1.5 percent, overall trends in total charges declined by about 0.5 percent, and overall trends in hospital mortality declined by about 2.0 percent. Costs are estimates calculated from charges based on Medicare cost-to-charge ratio. Our estimates do not include federal health care delivery sites. The National Vital Statistics System accounts for all deaths in the US but depends on the accuracy of the death certificates and therefore may underestimate mortality.27, 28

More than 16 million uninsured Americans have gained health insurance coverage since the Affordable Care Act’s provisions took effect. This sweeping legislation can be expected to change the landscape of care for GI illnesses. As health care access expands, and the financing of these services changes, researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and public health professionals now more than ever need a clear understanding of which conditions affect large portions of the populations and the costs inherent in the care of them. GI and liver diseases continue to account for substantial burden and cost in the United States.

FIGURE 1D.

Rising charges for hospitalizations for inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

FIGURE 1E.

Rising number of hospitalizations with principal diagnosis of liver disease

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This research was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, 1KL2TR001109 and a grant from the National Institutes of Health, T32 DK07634.

Appendix 1

Symptom Groupings from NAMCS/NHAMCS

| RFV1 | LABEL | COUNT | PERCENT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15451 | ‘Abdominal pain, cramps, spasms, NOS’ | 9435447 | 22.1691855 | Abdominal pain | 15028011 |

| 15453 | ‘Upper abdominal pain, cramps, spasms’ | 1136576 | 2.6704579 | ||

| 15452 | ‘Lower abdominal pain, cramps, spasms,’ | 1010634 | 2.3745491 | ||

| 15450 | Stomach and abdominal pain, cramps and spasms | 3445354 15028011 |

8.0950793 | ||

| 15950 | ‘Diarrhea’ | 4454522 | 10.466184 | Diarrhea | 4454522 |

| 15300 | ‘Vomiting’ | 2681315 | 6.2999209 | Vomiting | 2681315 |

| 15900 | ‘Constipation’ | 2472469 | 5.8092239 | Constipation | 2472469 |

| 15250 | ‘Nausea’ | 2343409 | 5.5059892 | Nausea | 2343409 |

| 16052 | ‘Anal-rectal bleeding’ | 1664572 | 3.9110183 | Bleeding | 2691658 |

| 15801 | ‘Blood in stool (melena)’ | 753950 | 1.7714537 | ||

| 15800 | ‘Gastrointestinal bleeding’ | 232363 | 0.5459517 | ||

| 15802 | ‘Vomiting blood (hematemesis)’ | 40773 2691658 |

|||

| 16051 | ‘Anal-rectal pain’ | 1445408 | 3.3960784 | Anorectal symptoms | 2446210 |

| 16054 | ‘Anal-rectal itching’ | 335186 | 0.7875409 | ||

| 16053 | ‘Anal-rectal swelling or mass’ | 179550 | 0.4218642 | ||

| 16050 | ‘Symptoms referable to anus-rectum’ | 447253 | 1.0508495 | ||

| 16004 | ‘Incontinence of stool’ | 38813 2446210 |

0.0911936 | ||

| 15350 | ‘Heartburn and indigestion (dyspepsia)’ | 1355288 | 3.1843357 | Heartburn and indigestion | 1355288 |

| 16150 | Other and unspecified symptoms referable to the digestive systemic | 1324906 | 3.1129513 | Other GI symptoms, unspecified | 1324906 |

| 15702 | ‘Decreased appetite’ | 837473 | 1.9676963 | Decreased appetite | 837473 |

| 15200 | ‘Difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia)’ | 808250 | 1.899035 | Dysphagia | 808250 |

| 16000 | Other symptoms or changes in bowel function | 722827 | 1.6983282 | Other changes in bowel function | 1307775 |

| 16003 | Changes in size, color, shape, or odor | 584948 1307775 |

1.3743727 | ||

| 15850 | ‘Flatulence’ | 582303 | 1.3681581 | Flatulence | 582303 |

| 16100 | Symptoms of liver, gallbladder, and biliary tract | 188353 | 0.4425474 | Symptoms related to the liver and biliary system | 411063 |

| 16102 | ‘Jaundice’ | 222710 411063 |

0.5232714 | ||

| 15651 | ‘Abdominal distention, fullness, NOS’ | 291507 | 0.6849143 | Abdominal distention | 373732 |

| 15653 | ‘Abdominal swelling, NOS’ | 70454 | 0.1655362 | ||

| 15650 | ‘Change in abdominal size’ | 11771 373732 |

0.0276567 | ||

| 15050 | ‘Symptoms referable to lips’ | 566403 | 1.3308 | ||

| 15001 | ‘Toothache’ | 504037 | 1.1842671 | ||

| 15652 | ‘Abdominal mass or tumor’ | 400400 | 0.9407654 | ||

| 15100 | ‘Symptoms referable to mouth’ | 336032 | 0.7895287 | ||

| 15104 | ‘Mouth ulcer, sore’ | 321258 | 0.7548162 | ||

| 15150 | ‘Symptoms referable to tongue’ | 296148 | 0.6958186 | ||

| 15053 | ‘Cold sore’ | 225644 | 0.530165 | ||

| 15051 | ‘Cracked, bleeding, dry lips’ | 116390 | 0.2734657 | ||

| 15103 | ‘Mouth dryness’ | 114517 | 0.269065 | ||

| 15701 | ‘Excessive appetite’ | 98399 | 0.2311947 | ||

| 15151 | ‘Tongue pain’ | 93304 | 0.2192237 | ||

| 15750 | ‘Difficulty eating’ | 90538 | 0.2127248 | ||

| 15011 | ‘Symptoms of the jaw, swelling’ | 78977 | 0.1855615 | ||

| 15400 | ‘Gastrointestinal infection’ | 77764 | 0.1827115 | ||

| 15101 | ‘Mouth pain, burning, soreness’ | 46531 | 0.1093276 | ||

| 15802 | ‘Vomiting blood (hematemesis)’ | 40773 | 0.0957988 | ||

| 15012 | ‘Symptoms of the jaw, lump or mass’ | 35988 | 0.0845561 | ||

| 15000 | ‘Symptoms of teeth and gums’ | 20218 | 0.0475035 | ||

| 15102 | ‘Mouth bleeding’ | 20158 | 0.0473625 |

Appendix 2

Inflation-adjusted charges for GI hospitalizations

Annual charges for C. diff-related hospitalizations, 1993 through 2012, National Inpatient Sample

| Year | Mean charges | Actual aggregate charges | Inflation - adjusted charges (2012 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | $11,548 | $273,595,216 | $434,711,557 |

| 1994 | $11,309 | $288,051,539 | $446,254,420 |

| 1995 | $11,719 | $286,588,145 | $431,751,434 |

| 1996 | $12,011 | $277,021,704 | $405,369,797 |

| 1997 | $13,119 | $317,230,539 | $453,795,815 |

| 1998 | $13,301 | $334,599,956 | $471,301,486 |

| 1999 | $14,316 | $417,783,828 | $575,754,263 |

| 2000 | $15,810 | $502,473,420 | $669,947,052 |

| 2001 | $18,372 | $652,867,392 | $846,861,220 |

| 2002 | $20,646 | $931,650,750 | $1,189,001,792 |

| 2003 | $24,040 | $1,139,399,840 | $1,421,735,689 |

| 2004 | $24,535 | $1,431,224,690 | $1,739,547,917 |

| 2005 | $26,809 | $1,973,437,299 | $2,319,966,018 |

| 2006 | $27,789 | $2,405,860,464 | $2,739,936,148 |

| 2007 | $31,499 | $3,154,089,367 | $3,492,587,098 |

| 2008 | $33,331 | $3,620,479,882 | $3,860,793,663 |

| 2009 | $33,779 | $3,560,948,401 | $3,810,868,928 |

| 2010 | $34,174 | $3,663,179,408 | $3,857,026,956 |

| 2011 | $35,334 | $4,194,039,798 | $4,280,833,352 |

| 2012 | $35,214 | $4,201,558,410 | $4,201,558,410 |

Annual charges for IBD-related hospitalizations (combined UC and Crohn’s), 1993 through 2012, National Inpatient Sample

| Year | Mean charges | Actual aggregate charges | Inflation-adjusted charges (2012 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | $12,805 | $751,423,010 | $1,193,925,360 |

| 1994 | $13,521 | $806,879,196 | $1,250,031,188 |

| 1995 | $13,448 | $802,805,256 | $1,209,444,029 |

| 1996 | $13,659 | $865,680,102 | $1,266,761,997 |

| 1997 | $14,090 | $920,401,070 | $1,316,626,562 |

| 1998 | $14,888 | $974,315,384 | $1,372,374,026 |

| 1999 | $14,796 | $1,053,874,692 | $1,452,360,781 |

| 2000 | $16,760 | $1,194,971,240 | $1,593,253,350 |

| 2001 | $18,288 | $1,408,761,216 | $1,827,362,275 |

| 2002 | $20,318 | $1,604,309,280 | $2,047,469,621 |

| 2003 | $22,545 | $1,907,442,270 | $2,380,094,024 |

| 2004 | $23,690 | $2,110,542,100 | $2,565,208,062 |

| 2005 | $25,355 | $2,229,744,055 | $2,621,279,347 |

| 2006 | $25,981 | $2,236,444,480 | $2,546,995,208 |

| 2007 | $28,299 | $2,443,194,165 | $2,705,398,429 |

| 2008 | $32,631 | $3,257,356,944 | $3,473,567,996 |

| 2009 | $32,872 | $3,181,878,112 | $3,405,194,084 |

| 2010 | $34,277 | $3,331,313,076 | $3,507,598,974 |

| 2011 | $35,679 | $3,566,936,667 | $3,640,752,636 |

| 2012 | $37,049 | $3,673,037,860 | $3,673,037,860 |

Annual charges for liver disease-related hospitalizations, 1993 through 2012, National Inpatient Sample

| Year | Mean charges | Actual aggregate charges | Inflation-adjusted charges (2012 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | $16,177 | $2,401,632,255 | $3,815,919,418 |

| 1994 | $18,094 | $2,756,797,142 | $4,270,877,753 |

| 1995 | $17,304 | $2,633,399,391 | $3,967,274,933 |

| 1996 | $17,722 | $2,799,163,282 | $4,096,055,415 |

| 1997 | $18,202 | $2,893,893,178 | $4,139,691,653 |

| 1998 | $17,673 | $2,920,518,969 | $4,113,703,265 |

| 1999 | $23,113 | $3,896,558,485 | $5,369,906,655 |

| 2000 | $21,669 | $3,839,816,809 | $5,119,621,954 |

| 2001 | $22,847 | $4,115,772,745 | $5,338,738,574 |

| 2002 | $25,504 | $4,752,736,726 | $6,065,591,083 |

| 2003 | $31,002 | $6,205,607,440 | $7,743,316,492 |

| 2004 | $29,434 | $6,006,104,668 | $7,299,976,682 |

| 2005 | $33,114 | $6,680,995,303 | $7,854,154,816 |

| 2006 | $32,355 | $6,684,530,895 | $7,612,739,019 |

| 2007 | $37,094 | $7,698,349,247 | $8,524,538,188 |

| 2008 | $43,984 | $9,770,589,440 | $10,419,124,266 |

| 2009 | $45,558 | $10,120,566,475 | $10,830,865,255 |

| 2010 | $46,466 | $10,780,950,651 | $11,351,455,292 |

| 2011 | $48,599 | $11,388,653,380 | $11,624,335,861 |

| 2012 | $49,611 | $12,063,851,846 | $12,063,851,846 |

Footnotes

Author Contributions: – AFP, ASB, SDC, ESD, SE, LMG, ETJ, JLL, SP, TR, MS, NJS, RSS - data collection, data analysis, conception and study design, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation. No conflicts of interest exist for any author.

References

- 1.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–87. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools. National Institutes of Health; Feb 5, 2015. Estimates of Funding for Various Research C, and Disease Categories. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. < http://report.nih.gov/categorical_spending.aspx%3E. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–11. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, et al. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1448–53. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, et al. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and upper gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:376–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States Part III: Liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1134–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howlader N NA, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/, based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.http://www.census.gov/popclock/data_tables.php?component=growth.

- 11.Ortman J, Velkoff V, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States Population. 2014 May 1; Retrieved June 1, 2015, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf.

- 12.Smith BD PN, Beckett GA, Ward JW. Hepatitis C virus antibody prevalence, correlates and predictors among persons born from 1945 through 1965, United States, 1999–2008. Hepatology. 2011;54(4 Suppl):554A–555A. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR. 2012;61(RR-04):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanyal AJ, Governing Board the Public Policy CPMcotA The Institute of Medicine report on viral hepatitis: a call to action. Hepatology. 2010;51:727–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velazquez RF, Rodriguez M, Navascues CA, et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:520–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Weinbaum CM, et al. Forecasting the morbidity and mortality associated with prevalent cases of pre-cirrhotic chronic hepatitis C in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17–22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang DX, Gross CP, Soulos PR, et al. Estimating the magnitude of colorectal cancers prevented during the era of screening: 1976 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120:2893–901. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Thompson TD, et al. Patterns of colorectal cancer test use, including CT colonography, in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:895–904. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tools & Resources – 80% by 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, from http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/.

- 24.Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, et al. Public health impact of achieving 80% colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States by 2018. Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonnenberg A. Hospitalization for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States between 1970 and 2004. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:297–300. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31816244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bewtra M, Su C, Lewis JD. Trends in hospitalization rates for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asrani SK, Larson JJ, Yawn B, et al. Underestimation of liver-related mortality in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:375–82. e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:825–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]