Abstract

Aims

This study investigated which ethyl glucuronide immunoassay (EtG-I) cutoff best detects heavy versus light drinking over five days in alcohol dependent outpatients.

Methods

A total of 121 adults with alcohol use disorders and co-occurring psychiatric disorders taking part in an alcohol treatment study. Participants provided self-reported drinking data and urine samples three time per week for 16-weeks (total samples = 2761). Agreement between low (100 ng/mL, 200 ng/mL), and moderate (500 ng/mL) EtG-I cutoffs and light (women ≤3 standard drinks, men ≤ 4 standard drinks) and heavy drinking (women >3, men >4 standard drinks) were calculated over one to five days.

Results

The 100 ng/mL cutoff detected >76% of light drinking for two days, and 66% at five days. The 100 ng/mL cutoff detected 84% (1 day) to 79% (5 days) of heavy drinking. The 200 ng/mL cutoff detected >55% of light drinking across five days and >66% of heavy drinking across five days. A 500 ng/mL cutoff identified 68% of light drinking and 78% of heavy drinking for one day, with detection of light (2–5 days <58%) and heavy drinking (2–5 days <71%) decreasing thereafter. Relative to 100 ng/mL, the 200 ng/mL and 500 ng/mL cutoffs were less likely to result in false positives.

Conclusions

An EtG-I cutoff of 100 ng/mL is most likely to detect heavy drinking for up to five days and any drinking during the previous two days. Cutoffs of ≥ 500 ng/mL are likely to only detect heavy drinking during the previous day.

Keywords: ethyl glucuronide in urine, alcohol biomarkers, assessment of cut-off, heavy drinking

1. INTRODUCTION

Absence of heavy drinking is approved by The Federal Drug Administration as an endpoint for evaluating the efficacy of new pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorders (FDA, 2015). A heavy drinking day is defined as over three standard drinks for women and over four standard drinks for men (FDA, 2015). Self-report instruments such as the Alcohol Timeline FollowBack (TLFB) are typically used in clinical research to determine whether light or heavy drinking has occurred (Sobell and Sobell, 2000). However, the validity of self-reported alcohol use varies (Babor et al., 2000; Del Boca and Noll, 2000), particularly when respondents face social, treatment, or legal contingencies for alcohol use (Langenbucher and Merrill, 2001).

In illicit drug use research, point-of-care drug urine tests capable of detecting use for two or more days are used to supplement self-report data (Donovan et al., 2012; Jatlow and O’Malley, 2010). A number of alcohol biomarkers detectable within urine samples are available to supplement self-report (Litten et al., 2010). Several studies have observed that when assessed in urine, ethyl glucuronide (EtG), a minor non-oxidative hepatic metabolite of ethanol (Wurst et al., 2000), can detect alcohol use for up to five days depending on the cutoff level used and the amount of alcohol consumed (Jatlow et al., 2014; Lowe et al., 2015). Our work has demonstrated that a commercially-available EtG-immunoassay (EtG-I; Diagnostic Reagents Incorporated, Sunnyvale, CA) can be accurately conducted by non-technical staff within 20 minutes using a bench-top analyzer (Indiko, ThermoFisher, Fremont, CA) that delivers results of a semi-quantitative EtG concentration in urine (Leickly et al., 2015). This process allows for the use of varying cutoff levels for identifying alcohol consumption. In the United States many commercial laboratories utilize a 500 ng/mL cutoff due to concerns about over-detection of alcohol use based on incidental non-beverage alcohol exposure (i.e. hand sanitizer; SAMHSA, 2012). However, research suggests that a much lower cutoff is needed to detect any level of drinking over the past two to five days (Jatlow and O’Malley, 2010; Jatlow et al., 2014; Lowe et al., 2015).

Little information exists regarding the ability of EtG to detect heavy versus light drinking in those receiving alcohol use disorder treatment. The present study investigated if low (100 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL) or moderate (500 ng/mL) EtG-I cutoffs are most suitable for identifying heavy versus light drinking for up to five days in alcohol dependent outpatients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHOD

Participants were 121 adults with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnoses of alcohol dependence and co-occurring mood (72%, n = 87) or psychotic (28%, n = 34) disorders. The average age was 46.9 years (SD = 10.3), and 65% (n = 79) of participants were male. Reported ethnicities were 52% (n = 63) Caucasian, 28% (n = 34) African-American, 10% (n = 12) Hispanic, 3% (n = 4) American Indian/Alaskan Native, 2% (n = 2) Asian/Pacific, and 5% (n = 6) multiracial or other ethnicities. Participants reported drinking on an average 15.8 days (SD = 8.5) of the previous 30 days.

Study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a contingency management intervention for alcohol dependence (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01567943). After enrollment they took part in a four-week pre-randomization period where they received reimbursement for submitting urine samples and providing self-reported alcohol use data. Those who completed this phase were randomized to 12-weeks of contingency management where they provided data and received prizes for submitting urine samples that tested negative for alcohol using EtG-I, or a non-contingent control group where they received prizes for providing urine samples regardless of EtG-I result. Participants received intensive outpatient addiction treatment at a treatment center in Seattle, WA. Urine samples and self-report data were collected three times each week for 16-weeks, and monthly during a 3-month follow-up period. Participants submitted up to 52 urine samples (M = 21.2, SD = 16.3) for EtG-I testing for a total of 2761 samples.

EtG immunoassays were conducted at the addiction clinic by research staff using spectrophotometry on a ThermoFisher Indiko analyzer (Fremont, CA). EtG enzyme immunoassay tests were conducted using EtG 100 ng/mL, 500 ng/mL, 1000 ng/mL, 2000 ng/mL, and Negative calibrators and EtG 100 ng/mL and 375 ng/mL controls. Antibody/Substrate and Enzyme Conjugate reagents were used and the analyzer was calibrated weekly. Samples were analyzed on the day of collection, and stored until analysis at 4°C with all calibrators, controls, and reagents. The immunoassay is linear up to 2000 ng/mL, with a reportable range of 0 ng/mL to 2000 ng/mL (the range of the lowest and highest calibrators). Dilution procedures were conducted when EtG-I concentrations displayed an error message indicating high absorbance. Fifty samples (2%) required dilution. Participants were advised to avoid non-beverage sources of ethanol. Creatinine was not measured, as recent research has shown these adjustments to be unnecessary (Jatlow et al., 2014; Stewart et al., 2013).

A measure based on the Alcohol Timeline FollowBack (Sobell and Sobell, 2000) was created to assess the hours since the last drinking episode, and the number of standard drinks consumed at the last drinking episode, variables which have the greatest impact on EtG test results. Self-reported hours since last alcohol use (up to 120 hours/5 days) and standard drinks consumed were assessed as continuous integers when each urine sample was collected. These data were recoded into no drinking, light drinking (women ≤3 standard drinks, men ≤ 4 standard drinks) or heavy drinking (women > 3 standard drinks, men > 4 standard drinks) over the prior one to five days.

Rates of light and heavy drinking were calculated and reported as frequencies and percentages. For each of the five assessment periods (i.e., 1 day to 5 days) the number and percent of light and heavy drinking detected by each EtG-I cutoff was calculated. The rate of positive EtG-I samples when no alcohol use was reported in the last 5 days was calculated. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of heavy drinking was not conducted because light drinking, when present, would confound the results of this analysis. Analyses were conducted in SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, 2010).

3. RESULTS

Heavy drinking during the previous five days was reported in 29% (810/2761) of study visits, while light drinking was reported in 17% of (478/2761) visits. The mean number of standard drinks reported during the last drinking episode was 3.7 (SD = 6.4). EtG-I results were positive in 48% (1312/2761) of the samples at 100 ng/mL, 37% (1022/2761) of the samples at 200 ng/mL, and 31% (842/2761 at 500 ng/mL. The mean EtG-I value was 596.7 ng/mL (SD = 824.7 ng/mL); the median value was 89.2 ng/mL.

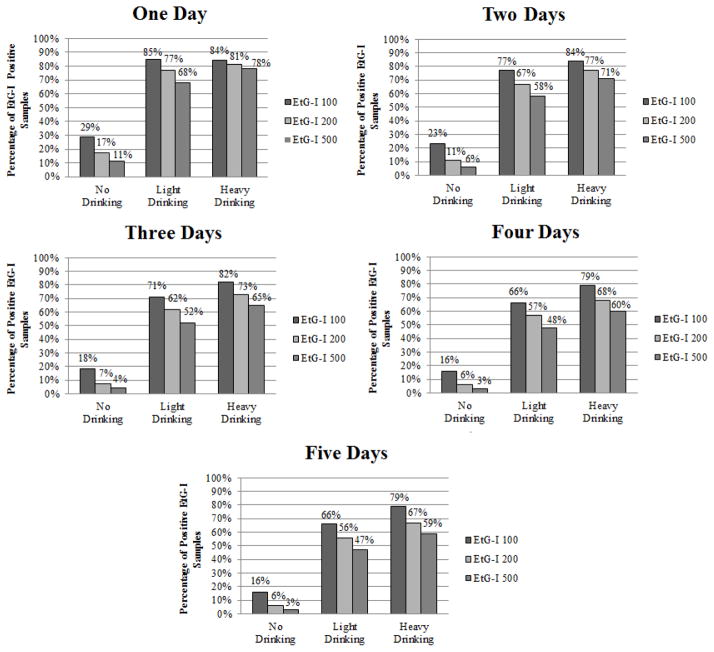

Figure 1 displays the percentage of EtG-I positive results from one to five days prior, as well as the percentage of these results that indicate no drinking, light, or heavy drinking at the 100 ng/mL, 200 ng/mL, and 500 ng/mL EtG-I cutoff levels. The 100 ng/mL cutoff level had the highest rate of detection for light and heavy drinking across the five day assessment period. The 100 ng/mL cutoff identified 85% of light drinking for one day, with rates of detection of light drinking declining to 66% over five days. The 100 ng/mL cutoff detected 84% (day 1) to 79% (day 5) of heavy drinking. The 200 ng/mL cutoff identified 77% of light and 81% of heavy drinking for one day, with identification of light and heavy drinking decreasing thereafter. The 500 ng/mL cutoff identified 68% of light drinking for one day, with detection of < 58% for two through five days. The 500ng/mL cutoff identified 78% of heavy drinking for one day and < 71% of heavy drinking for two to five days. False positives were highest for 100 ng/mL (1 day = 29% to 5 days = 16%), relative to higher cutoffs.

Figure 1.

Percentage of positive ethyl glucuronide immunoassay samples at each time point, and percentage of drinking that was considered light drinking (women ≤3 standard drinks, men ≤ 4 standard drinks) heavy drinking (women >3 standard drinks, men >4 standard drinks) at each time point. A total of 2,761 urine samples analyzed at each time point.

4. DISCUSSION

This study builds upon the growing literature suggesting that relatively low EtG cutoff levels are needed to detect alcohol use for more than two days (Dahl et al., 2011; Hegstad et al., 2013; Jatlow et al., 2014; Lowe et al., 2015; Stewart et al., 2013). In fact, results suggest that the relatively low cutoff of 100 ng/mL is able to identify 79% of heavy drinking over the previous five days. Therefore, when attempting to detect heavy drinking, a cutoff of 100 ng/mL is recommended. Importantly, even at this relatively low cutoff, EtG-I detected relatively low levels of light drinking after two days.

The 500 ng/mL cutoff used by many commercial laboratories leads to a precipitous decline in detection of light and heavy drinking across all time periods relative to 100 ng/mL. The only benefit of utilizing the 200 and 500 ng/mL cutoffs versus 100 ng/mL cutoff was the lower frequency of false positives observed using these higher cutoffs (500 ng/mL = 3%, 200 ng/mL = 6%, 100 ng/mL = 16% over 5 days). The differential rates of false positives could be due to several factors including the 100 ng/mL cutoff being more likely to identify drinking beyond five days and the possibility of inaccurate self-report.

Other methodologies, such as controlled drinking paradigms, provide standardized methods for assessing biomarkers such as EtG-I (Jatlow et al., 2014). Nevertheless, use of self-reported drinking as a validity outcome provides an opportunity to evaluate the accuracy of EtG-I in samples where controlled drinking experiments are inappropriate.

Despite these potential limitations, results of this study suggest that the 100 ng/mL EtG-I cutoff of is most likely to detect heavy drinking over five days. In contrast, the 500 ng/mL cutoff used by most drug testing laboratories and a recently released point-of-service EtG-I (Premier Biotech, Excelsior, MN) exhibits low levels of detection for heavy drinking for more than one day. Therefore, cutoffs of 200 ng/mL and above are recommended for use in settings where minimizing false positives is essential. When used in clinical and research settings, a 100 ng/mL cutoff is recommended to maximize detection of heavy drinking. These results support the appropriateness of EtG-I as a measure of recent heavy drinking.

Highlights.

Multiple cutoffs for ethyl glucuronide immunoassay (EtG-I) were compared with drinking self-report.

The 100 ng/mL cutoff is most likely to detect heavy drinking up to five days.

The 500 ng/mL cutoff is likely to only detect heavy drinking during the previous day.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institue on Alochol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA02024801A1; PI McDonell); the NIAAA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Michael G. McDonell designed the study, assisted in conceptualization, conducted data analyses and wrote the manuscript. Jordan Skalisky conducted study procedures, data analyses and assisted in writing the manuscript. Emily Leickly conducted study procedures and assisted in writing the manuscript. Sterling McPherson provided input into study design, data analyses and manuscript review. Samuel Battalio conducted study procedures and reviewed the manuscript. Jenny R. Nepom provided consultation in writing the manuscript. Debra Srebnik, John Roll, and Richard K. Ries provided input into study design and manuscript review.

Conflict of Interest

Michael G. McDonell, Jordan Skalisky, Emily Leickly, Samuel Battalio, Jenny R. Nepom, and Debra Srebnik have no disclosures to report.

Sterling McPherson and John Roll have received research funding from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. This funding is in no way related to the investigation reported here. Sterling McPherson and John Roll have no disclosures to report.

Rick Ries has been on the speaker of bureaus of Janssen, Alkermes, and Reckitt Benckiser in the past three years but has no disclosures to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR : Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Press Inc; Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton R, Del Boca F. Talk is cheap: measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl H, Carlsson AV, Hillgren K, Helander A. Urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate testing for detection of recent drinking in an outpatient treatment program for alcohol and drug dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:278–282. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Noll JA. Truth or consequences: the validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 3):S347–360. doi: 10.1080/09652140020004278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bigelow GE, Brigham GS, Carroll KM, Cohen AJ, Gardin JG, Hamilton JA, Huestis MA, Hughes JR, Lindblad R, Marlatt GA, Preston KL, Selzer JA, Somoza EC, Wells EA. Primary outcome indices in illicit drug dependence treatment research: systematic approach to selection and measurement of drug use end-points in clinical trials. Addiction. 2012;107:694–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA. Alcoholism: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm433618.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hegstad S, Helland A, Hagemann C, Michelsen L, Spigset O. EtG/EtS in urine from sexual assault victims determined by UPLC-MS-MS. J Anal Toxicol. 2013;37:227–232. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkt008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 19.0) IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jatlow P, O’Malley SS. Clinical (nonforensic) application of ethyl glucuronide measurement: are we ready? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:968–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatlow PI, Agro A, Wu R, Nadim H, Toll BA, Ralevski E, Nogueira C, Shi J, Dziura JD, Perakis IL, O’Malley SS. Ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate assays in clinical trials, interpretation, and limitations: results of a dose ranging alcohol challenge study and 2 clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acer.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher J, Merrill J. The validity of self-reported cost events by substance abusers. Limits, liabilities, and future directions. Eval Rev. 2001;25:184–210. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leickly E, McDonell MG, Vilardaga R, Angelo FA, Lowe JM, McPherson S, Srebnik s, Roll JM, Ries RK. High levels of agreement between clinic-based ethyl glucuronide (EtG) immunoassays and laboratory-based mass spectrometry. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41:246–250. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1011743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Bradley AM, Moss HB. Alcohol biomarkers in applied settings: recent advances and future research opportunities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:955–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, McDonell M, Leickly E, Angelo F, Vilardaga R, McPherson S, Srebnik D, Roll J, Ries R. Determining ethyl glucuronide cutoffs when detecting self-reported alcohol use in addiction treatment patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:905–910. doi: 10.1111/Acer.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. The Role of Biomarkers in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders, 2012 Revision. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2000. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Koch DG, Burgess DM, Willner IR, Reuben A. Sensitivity and specificity of urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate in liver disease patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Kempter C, Metzger J, Seidl S, Alt A. Ethyl glucuronide: a marker of recent alcohol consumption with clinical and forensic implications. Alcohol. 2000;20:111–116. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]