Abstract

Background

Substance use and depression often co-occur, complicating treatment of both substance use and depression. Despite research documenting age-related trends in both substance use and depression, little research has examined how the associations between substance use behaviors and depression changes across the lifespan.

Methods

This study examines how the associations between substance use behaviors (daily smoking, regular heavy episodic drinking (HED), and marijuana use) and depressive symptoms vary from adolescence into young adulthood (ages 12 to 31), and how these associations differ by gender. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), we implemented time-varying effect models (TVEM), an analytic approach that estimates how the associations between predictors (e.g., substance use measures) and an outcome (e.g., depressive symptoms) vary across age.

Results

Marijuana use and daily smoking were significantly associated with depressive symptoms at most ages from 12 to 31. Regular HED was significantly associated with depressive symptoms during adolescence only. In bivariate analyses, the association with depressive symptoms for each substance use behavior was significantly stronger for females at certain ages; when adjusting for concurrent substance use in a multivariate analysis, no gender differences were observed.

Conclusions

While the associations between depressive symptoms and both marijuana and daily smoking were relatively stable across ages 12 to 31, regular HED was only significantly associated with depressive symptoms during adolescence. Understanding age and gender trends in these associations can help tailor prevention efforts and joint treatment methods in order to maximize public health benefit.

Keywords: Depression, Substance use, Comorbidity, Adolescence, Young adulthood, Age-varying effects

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders and depression are highly correlated in the general population (Hasin et al., 2012; Regier et al., 1990). Population-based surveys estimate that the rate of lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) among individuals with nicotine dependence is 17%, with alcohol dependence is 38%, and with other drug dependence is 49% (Conway et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2004). Conversely, among individuals with lifetime MDD, 30% have nicotine dependence, 21% have alcohol dependence, and 6% have other drug dependence (Hasin et al., 2005). The comorbidity with depression has been found to be robust across substances, with the link between smoking and depression being particularly well-documented (Dierker et al., 2015; Kassel et al., 2003). The smoking – depression association holds for various classifications of smokers (e.g., ever, regular, and heavy smokers; Husky et al., 2008; Payne et al., 2013) as well as various stages of the smoking trajectory (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2011; Dierker and Donny, 2008; McKenzie et al., 2010; Leventhal et al., 2012). Smokers experience more depressive symptoms, a higher prevalence of lifetime MDD, and more depressive episodes than non-smokers (Wiesbeck et al., 2008; Wilhelm et al. 2006; Ziedonis et al., 2008). Alcohol use has also been linked to depression. A recent study suggests a dose-response relationship between alcohol disorder severity and depression: incidence of depressive disorders was 4% in individuals who met none of the DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria and increased to 45% in individuals who met all ten criteria (Boschloo et al., 2012). Similarly, marijuana use has been shown to co-occur with depression. National epidemiologic data indicate 29% of those with lifetime marijuana abuse and 47% of those with marijuana dependence met lifetime criteria for MDD (Conway, 2006). Additionally, marijuana use, especially heavy use, has been shown to be associated with depression among adolescents in the general population (Fergusson et al., 2002; Patton et al., 2002; Rey et al., 2002).

Although the co-occurrence of substance use behaviors and depression is well-established, little research has investigated age trends in these associations. Rates of substance use and depression both show notable age trends and both peak in adolescence. It is plausible that the associations between substance use behaviors and depression are also stronger during adolescence, as the profound physiological and social developmental processes occurring during adolescence may heighten vulnerability. Substance use in early adolescence is less normative and typically occurs among youth who face a myriad of risk factors, including adverse early life events, lack of parental involvement, or family and peer substance use (Green et al., 2012); substance use becomes more normative with age (SAMHSA, 2014). Thus, age-varying associations between substance use and depression may reflect age-varying risk profiles of substance users due to changes in the meaning and context of substance use over time. Alternatively, stronger associations in adolescence may reflect the imbalance in arousal and regulation that characterizes the developing adolescent brain: pubertal maturation increases emotional arousal, sensation-seeking, and reward orientation, yet adolescents do not have fully formed executive functioning to help regulate and inhibit behavior (Crews et al., 2007; Guerri and Pascual, 2010; Steinberg, 2005). In the absence of well-developed executive functioning, adolescents may have fewer cognitive and emotional resources to cope with life stressors, so they may be more likely than individuals at other ages to engage in substance use to relieve depressive symptoms (e.g., self-medicate). Furthermore, social acceptance and peer norms are extremely salient during adolescence (Christie and Viner 2005; Eisenberg et al., 2014); youth who use substances due to these external social motivations may experience greater cognitive dissonance and distress, potentially heightening their risk for depressive symptoms. Finally, neuroscience research has shown heavy substance use to be associated with decreased neural plasticity and structural abnormalities in the brain, which may result in both short- and long-term behavioral impairments. Specifically, youth with an alcohol use disorder show structural deficits in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex compared to youth without an alcohol use disorder (De Bellis et al., 2000; Nagel et al. 2005; Medina et al., 2008). Given that these regions are central to emotion regulation, these deficits may heighten vulnerability for depression.

The few studies to date investigating age trends have yielded mixed findings. While studies among adults typically focus on clinical definitions of substance use disorders and MDD, studies of adolescents and young adults often define these constructs more broadly as substance use and depressive symptoms, as younger individuals may be in earlier stages of substance use and depression onset and not yet meet clinical definitions. Early studies found that substance use disorders were more strongly associated with depression for those over age 30 compared to those under age 30 (Grant, 1995), and that comorbid mental health problems and alcohol dependence were more common at older ages, whereas comorbidity with alcohol abuse was more common at younger ages (Grant and Harford, 1995). Fergusson et al. (2002) found that marijuana use is more strongly associated with suicidal ideation for adolescents compared to young adults, while Pedersen (2008) found that the association may be stronger for young adults. Poulin et al. (2005) found that the association between heavy episodic drinking (HED) and depression varied by age for females but not males. A recent study regarding nicotine dependence and depression found that this association was constant across adolescence and young adulthood (Dierker et al., 2015).

Furthermore, despite notable gender differences in the prevalence of alcohol and substance use disorders, which are more common among men (Conway et al., 2006), and depression, which is more common among women (Hasin et al., 2005), few studies have examined gender differences in the associations between substance use and depression. Existing studies that have stratified on gender provide some evidence that these associations are stronger among women. Specifically, Acierno et al. (2000) reported a significant association between heavy smoking and depressive disorder among female adolescents but not male adolescents. Tu et al. (2008) found that poor mental health was associated with marijuana use among adolescent females but not males; similarly, Patton et al. (2002) found that marijuana use was associated with depression both cross-sectionally and longitudinally among adolescent females but not males. Poulin et al. (2005) reported that alcohol use and smoking were associated with elevated depressive symptoms in adolescent females, but not males, whereas marijuana use was associated with depressive symptoms for both genders. In adults, the association between marijuana dependence and MDD was nearly twice as strong for women than men (Conway, 2006), and among those with lifetime alcohol dependence, women had nearly twice the rate of lifetime depression as men (Kessler et al., 1997). Potential mechanisms that may explain these gender differences include greater neurotoxicity of substances (particularly alcohol) in females due to smaller body size (Guerri and Pascual, 2010), differences in timing of brain development and effects of substances on the brain arising from hormonal differences (Medina et al., 2008), and differential salience of social support and peer norms by gender (Gutman and Eccles, 2007).

Despite previous studies examining the associations between substance use and depression, gaps in the literature persist. In particular, little is known about how the strength of the associations between substance use behaviors and depression change by age, as most studies of this topic examined only adolescents or only adults. This study was designed to elucidate how the associations between substance use behaviors (daily smoking, marijuana use, and HED) and depressive symptoms change from early adolescence into young adulthood (age 12 to 31), using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). We define substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms more broadly for two reasons: (1) to assess whether the associations previously observed between substance use disorders and MDD generalize to substance use and depressive symptoms and (2) to facilitate examination of these associations in younger individuals, who may be in earlier stages of substance use and depression onset. We implement time-varying effect modeling (TVEM), an analytic approach that estimates the associations between predictors (e.g., smoking, marijuana use, and HED) and an outcome (e.g., depressive symptoms) as functions of continuous age. In all analyses, we examine whether gender moderates these age-varying associations. Given the increasing recognition of substance use and depression comorbidity and interest in concurrent treatment, this study was designed to elucidate critical age windows in which these associations are strongest and concurrent treatment may be most beneficial.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study uses public-use data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; Harris et al., 2009). Add Health is a nationally representative, longitudinal study of adolescents that focused on how behaviors and social environments during adolescence are linked to adult outcomes (Harris, 2011). Wave I of Add Health was conducted as in-school and in-home interviews while participants were in the 7th - 12th grades (1994-1995). Three follow-up surveys were conducted: Wave II during 1995-1996 (participants in the 12th grade during Wave I were excluded); Wave III during 2001-2002; and Wave IV during 2007-2008. Individuals who provided substance use and depressive symptoms data during at least one Add Health wave were eligible for inclusion in our analysis. We restricted our sample to measurement occasions at which individuals were ages 12 to 31, due to data sparseness outside of this age range. Of the original 6,504 individuals in the public use data, our sample included 6,070 individuals (93%) and 19,893 measurement occasions (an average of 3.3 per individual). Fifty one percent (51%) of individuals were female; 70% identified as White, 19% identified as Black, and 11% as other race; 12% were of Hispanic ethnicity.

2.2 Measures

Depressive symptoms during the past seven days were measured at each wave with a subset of nine items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). This short form of the CES-D has good reliability and has been used widely in studies of adolescent depression (Dunn et al., 2013). In our overall sample, the Cronbach's α=0.80; internal consistency was invariant across age. The items included “bothered by things that usually don't bother you,” “could not shake off the blues,” “felt that you were just as good as other people [reverse coded],” “had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing,” “were depressed,” “were too tired to do things,” “enjoyed life [reverse coded],” “were sad,” and “felt that people disliked you.” Each item was rated on a scale of 0-3, representing whether an individual experienced the symptom “never/rarely” to “most/all of the time.”

We examined three substance use behaviors: daily smoking, past-month marijuana use, and regular HED. Smoking was assessed as days smoked out of the past 30 days; this was dichotomized to indicate whether individuals smoked on all of the past 30 days. Marijuana use was assessed as times used during the past month; this was dichotomized into any/no past month marijuana use. Frequency of HED (Wave I-III definition: 5+ drinks; Wave IV definition: 4+ drinks for females, 5+ drinks for males) during the past year was assessed; this was dichotomized into any/no regular past year HED, where regular HED was defined as at least one time per month for the past 12 months.

2.3 Analysis

Analyses were conducted using time-varying effect modeling, a type of non-parametric spline regression that estimates the associations between predictors and an outcome as continuous functions of time (Hastie and Tibshirani, 1993; Tan et al., 2012). In these analyses, our time metric was age (coded to the nearest month). By using data from all 4 waves of Add Health, our sample comprehensively spanned the age range from 12 to 31.

Standard longitudinal models (e.g., mixed models, growth curve models, etc.) are often specified with a regression term for time, and thus yield a single point estimate for the time effect. In contrast, TVEM estimates a function that represents the regression coefficient between the predictor and outcome across continuous time. Thus, unlike in more traditional models, time effects are not forced to adhere to a parametric function, but rather are flexibly estimated as nonparametric. This regression coefficient function, along with the corresponding 95% confidence interval, is best presented graphically. TVEM is particularly well-suited to investigate dynamic associations across developmental age, as demonstrated in recent studies by Evans-Polce et al. (2015) and Vasilenko and Lanza (2014). Additional technical details on TVEM, including differences between TVEM and other longitudinal models, are available elsewhere (Lanza et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2012; Vasilenko et al., 2014).

We first modeled the age trends in mean depressive symptoms and prevalence of daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular HED, using a separate intercept-only TVEM for each. These models were estimated separately for males and females. To examine the age-varying associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms, we implemented TVEM in which daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular HED predicted depressive symptoms. We first estimated the independent age-varying association with depressive symptoms for each substance use behavior. We also estimated the adjusted age-varying associations using all three substance use behaviors as simultaneous predictors. To determine whether gender modified these complex associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms at any point across the age span, all analyses were stratified by gender. In all models, we controlled for race (White, Black, other) and Hispanic ethnicity by specifying these as time-invariant covariates. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 and TVEM was implemented using the SAS macros %normal_TVEM and %logistic_TVEM; these macros are available for download at methodology.psu.edu (Li et al., 2014). All TVEM models used the p-spline estimation method.

3. Results

3.1 Depressive symptoms and substance use across adolescence and early adulthood

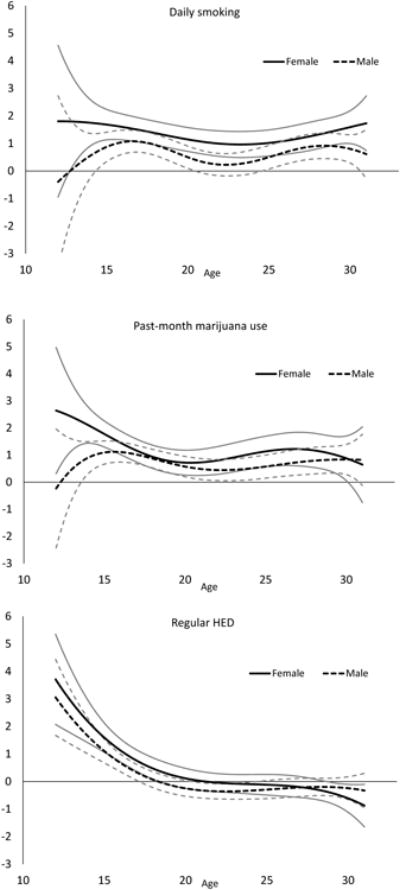

Although males and females had similar levels of depressive symptoms at age 12 (mean scores of approximately 4.5), females consistently reported greater symptoms than males during most of adolescence and early adulthood (Fig. 1). Depressive symptoms peaked for females at approximately age 16, with a mean score of 6.8 (95% CI = [6.7, 7.0]). Males peaked slightly later at age 17.5, with a mean score of 5.3 (95% CI = [5.2, 5.5]).

Fig. 1.

Past-week mean score on the 9-item CESD across ages 12 to 31 for males and females.

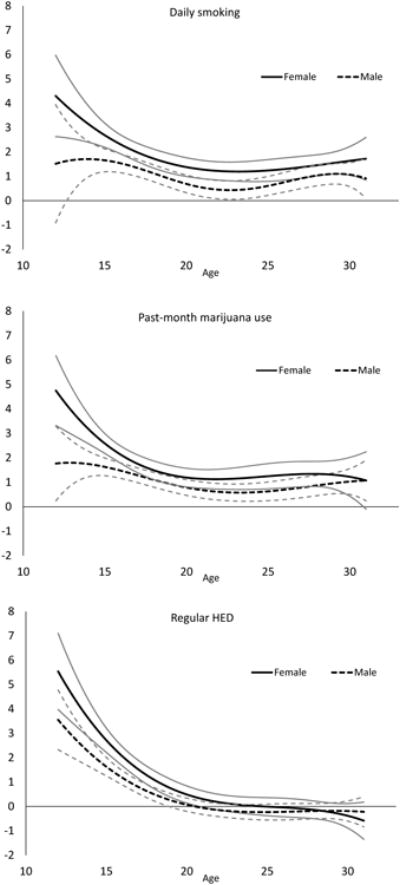

Fig. 2 shows the rates of daily smoking, regular HED and past-month marijuana use as continuous functions of age from 12 to 31, stratified by gender. Daily smoking rates were very similar between males and females throughout adolescence, rising steadily until approximately age 20 (females: 20%; males: 23%). In early adulthood, female rates remained fairly stable; male rates continued to rise and were significantly higher than female rates until the late 20s, when male rates declined slightly. The rate of marijuana use was similar between genders in early adolescence; by age 17, male and female rates had diverged, with males reporting significantly higher use at all ages 17 to 31. Marijuana use peaked around age 20 for both genders (females: 19%; males: 27%), and then declined for both genders from age 20 to age 31. By age 31, the rate of use among males was twice as high as among females (18% versus 9%). Rates of regular HED also showed notable gender differences across age, with females reporting significantly lower rates of regular HED than males at all ages 16 to 31. Furthermore, the trajectories for males and females were notably different. Among males, regular HED increased from age 12 to a peak prevalence of 56% at approximately age 22 and then steadily decreased to age 31. In contrast, females showed a more variable HED trajectory, with a plateau near 10% from age 15 to 17 and two peaks during their 20s (43% prevalence at ages 21 and 27).

Fig. 2.

Estimated prevalence of daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular heavy episodic drinking across ages 12 to 31 for males and females. Gray lines represent 95% confidence interval bounds.

3.2 Age-varying associations between substance use and depressive symptoms

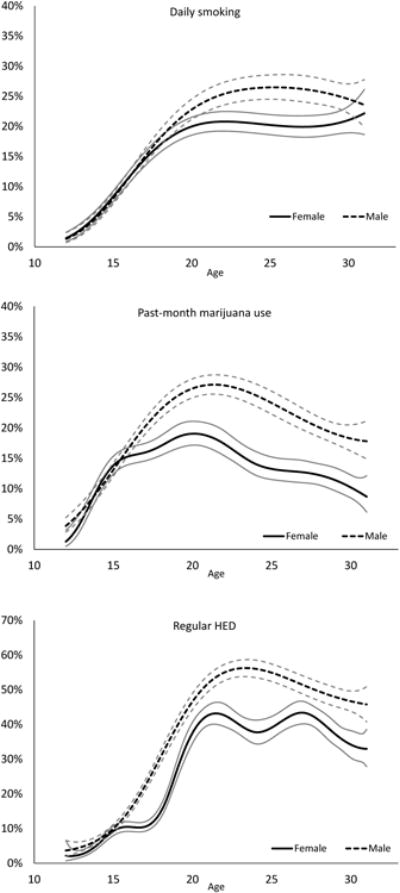

We first examined bivariate age-varying associations between depressive symptoms and, respectively, daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular HED (Fig. 3). To this end, we implemented separate models in which each substance use behavior predicted depressive symptoms; models were estimated separately for males and females. For each substance use behavior, we observed a significant positive association with depressive symptoms during adolescence; this association persisted into early adulthood for daily smoking and marijuana use. Specifically, daily smoking was significantly associated with elevated depression scores from ages 12 to 31 for females and from ages 12.5 to 31 for males, with the strongest associations during early adolescence. Among 12-year old females, daily smokers had mean depression scores 4.3 points higher than non-daily smokers (95% CI = [2.6, 5.9]). This relationship peaked at age 13.5 for males: daily smokers reported mean depression scores 1.7 points higher than non-daily smokers (95% CI = [0.7, 2.8]). Some gender effects were observed, as the association among females was significantly stronger than the association for males from approximately age 14.5 to 16 and from 21 to 23. Marijuana use was also significantly associated with depressive symptoms from ages 12 to 31 for both genders; again, this association was strongest during adolescence. Among 12-year old females, marijuana users had mean depression scores 4.7 points higher than non-users (95% CI = [3.3, 6.2]); 12-year old male marijuana users reported mean depression scores 1.8 points higher than non-users (95% CI = [0.2, 3.3]). The association among females was significantly stronger than the association among males during ages 12 to 16. In contrast, regular HED was only significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms during adolescence – this association was not significant after age 19 for males and age 21 for females. During adolescence, regular HED had a stronger association with depressive symptoms than either marijuana use or daily smoking. Among 12-year old females, those with regular HED reported mean depression scores 5.5 points higher than non-users (95% CI = [4.0, 7.1]); 12-year old males with regular HED reported mean depression scores 3.6 points higher than non-users (95% CI = [2.3, 4.8]). Again, gender effects were observed, with the association significantly stronger for females than males during ages 14 to 17.

Fig. 3.

Age-varying coefficient functions depicting the bivariate associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms for males and females. Gray lines represent 95% confidence interval bounds.

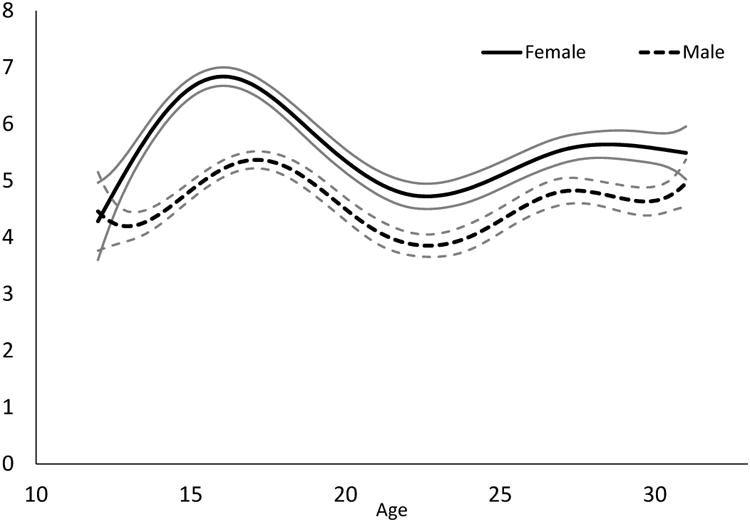

Since individuals often use multiple substances simultaneously, the bivariate association between a given substance use behavior and depressive symptoms may be confounded by concurrent substance use behaviors. Therefore, we also estimated a multivariate TVEM in which daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular HED simultaneously predicted depressive symptoms in order to estimate age-varying associations while adjusting for concurrent substance use behaviors (Fig. 4). Generally, the results from the multivariate model were similar to the results from the bivariate models, with the adjusted associations somewhat attenuated. However, in the adjusted analysis, there were no significant gender differences at any age for any of the three substance use behaviors. When adjusting for marijuana use and regular HED, daily smoking was significantly associated with higher depression scores for females during ages 12.5 to 31, and for males during ages 14.5 to 20.5 and 24.5 to 30.5. As in the bivariate model, this association was strongest during adolescence for both males and females, peaking at age 12.5 for females (1.8 point higher mean depression score, 95% CI = [0.05, 3.5]) and at age 16.5 for males (1.1 point higher mean depression score, 95% CI = [0.7, 1.5]). After adjusting for daily smoking and regular HED, marijuana use was significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms among females during ages 12 to 30 and among males during ages 13.5 to 30.5. This association peaked in adolescence for both genders, at age 12 for females (2.6 point higher mean depression score, 95% CI = [0.3, 4.9]) and at age 15.5 for males (1.1 point higher mean depression score, 95% CI = [0.7, 1.5]). After adjusting for daily smoking and marijuana use, regular HED was associated with elevated depressive symptoms only during adolescence for both females (until age 18.5) and males (until age 17). For both genders, this association was strongest at age 12: females with regular HED had mean depression scores 3.7 points higher than non-users (95% CI = [2.1, 5.3]), and males reporting regular HED had mean depression scores 3.1 points higher (95% CI = [1.7, 4.4]).

Fig. 4.

Age-varying coefficient functions depicting the multivariate associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms for males and females. Gray lines represent 95% confidence interval bounds.

4. Discussion

Although many prior studies have investigated the associations between substance use disorders and depression, this study is novel in that we examined how the broader associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms varied with age and by gender across adolescence and young adulthood (ages 12-31) using national data. We implemented both bivariate analyses of depressive symptoms with, respectively, daily smoking, marijuana use, and regular HED, as well as a multivariate analysis that accounted for concurrent substance use. Our results demonstrated significant positive associations between depressive symptoms and all three substance use behaviors during adolescence, with regular HED showing the strongest association, confirming that the associations observed between substance use disorders and MDD do generalize. Marijuana use and daily smoking both exhibited a relatively stable association with depressive symptoms throughout adolescence and early adulthood for both genders. For both daily smoking and marijuana use, the magnitude of the associations in adolescence was not statistically different from the magnitude of the association in adulthood, suggesting that age does not significantly moderate these associations. These results, which suggest a chronic comorbidity, are consistent with recent studies that found that the association between smoking and depression is established early and persists (Dierker et al., 2015; Leventhal and Zvolenksy, 2015). In contrast, the magnitude of association between regular HED and depressive symptoms was age-dependent. For both genders, the association was strong during early adolescence, decreased steadily during adolescence, and was no longer significant for either gender after age 18. These observed age trends may reflect that alcohol consumption and HED becomes normative and highly prevalent with age, unlike marijuana or cigarette use; 23% of individuals age 12 or older and 43% of adults 21 to 25 report past-month HED (SAMHSA, 2013). Several potential mechanisms could explain the age-varying association for HED. Selection bias may be at play such that the relatively few individuals engaging in regular HED in early adolescence have a higher risk for depression due to behavioral, familial, and environmental risk factors. Alternatively, adolescents at-risk for depression may be more likely to use alcohol for self-medication than adults, potentially because their executive functioning abilities are not fully developed. Finally, heavy alcohol use during early adolescence may lead to an elevated risk for depressive symptoms by engendering short-term impairment in executive functioning; the diminished association in adulthood might suggest that any impairment is not long-term.

When considering the bivariate associations, significant gender differences were observed at various ages; these gender effects were not observed in the multivariate analysis. Additionally, the associations between depressive symptoms and all three substance use behaviors were somewhat attenuated in the multivariate analyses, particularly during adolescence. One potential explanation is that the bivariate analyses were partially confounded by concurrent substance use. It is possible that the stronger associations among females in the bivariate analyses reflects higher rates of co-occurring substance use behaviors among females, rather than an inherently stronger association between a specific substance use behavior and depression. Notably, many previous studies, including those finding gender effects, have typically examined the relationship between depression and a single substance use behavior, without controlling for other substance use behaviors. Alternatively, the effect of multiple substance use behaviors may not strictly be additive, but rather, polysubstance use may represent a phenotypically distinct phenomenon, with a unique risk for depression. Future research focused specifically on the associations between polysubstance use and depression would shed light on this.

Several limitations of our analyses merit consideration. First, all data in Add Health were self-reported and thus may be subject to recall bias or social desirability bias. Second, during the first 3 waves of Add Health, HED was defined as 5+ drinks, whereas at Wave 4, the modern gender-specific definition of HED was implemented (4+ drinks for females, 5+ drinks for males). Thus, changes in the association with HED over time may partially reflect this change in measurement. Third, it is possible that cohort effects may be present; yet, given the relatively small age range (approximately 6 years) of individuals enrolled at Wave 1, these effects should be minimal. Fourth, we considered dichotomous measures of substance use behaviors in order to increase our statistical power at young ages when substance use is rare; however, use of categorical or continuous measures could provide more nuanced information regarding these associations. Fifth, lower base rates of behavior and lower variances at younger ages may limit statistical power during this age period; however, both the large sample sizes and the numerous significant associations we observed at younger ages mitigates concerns regarding power. Finally, our analyses estimate associations, rather than causal effects or directional relationships between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms.

The co-occurrence of substance use and depression has important implications for the treatment both of substance use and mental health problems, as individuals with co-occurring disorders often have more severe substance use and mental health problems compared to individuals with standalone disorders (Couwenberg et al., 2006; Grella et al., 2001; Rowe et al., 2004). Comorbidity is associated with worse alcohol and drug treatment outcomes among both adults (Brown et al., 2004; Compton et al., 2003; Timko et al., 2010) and adolescents (Cornelius et al., 2004; Vourakis, 2005; White et al., 2004), as well as higher rates of suicide (Davis et al., 2008). Our results demonstrate significant associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms throughout adolescence and young adulthood and allude to a role of polysubstance use in depression. Thus, it is critical that prevention and treatment efforts focus jointly on substance use behaviors and depression among this population. A similar recommendation was made by Brook et al. (2014), who advised that treatment for depression should particularly emphasize tobacco prevention and cessation. The chronicity of the associations between depressive symptoms and daily smoking and marijuana use, particularly among females, highlight that prevention and treatment efforts during adolescence could markedly disrupt this comorbidity. With regard to alcohol, the crucial window for intervention appears to be early adolescence, when the comorbidity association is the strongest. While treatment modalities that jointly address depression and substance use have not been well-developed, particularly for adolescents, one promising approach is integrated CBT that focuses on both substance use and depression (Curry et al., 2003). Additionally, a recent study comparing sequential and simultaneous substance use and depression treatment found both to be efficacious (Rohde et al., 2014). Overall, our results highlight notable variation in the association between depressive symptoms and substance use by age, and potentially by gender, suggest that tailoring of prevention and treatment efforts to particular age-gender combinations may produce the greatest public health benefit.

Age trends in comorbid substance use behaviors and depression are poorly understood

We used time-varying effect modeling to examine these age-varying associations

Marijuana use was associated with depressive symptoms at most ages 12-31

Daily cigarette use was associated with depressive symptoms at most ages 12-31

Regular heavy episodic drinking (HED) was associated with depressive symptoms only during adolescence

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources: Development of this article was funded by awards P50DA010075 and T32DA017629 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and award R01 CA168676 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health. This study's funding source had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to study conception and analysis plan. Schuler analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Megan S. Schuler, Email: schuler@hcp.med.harvard.edu, msschuler@gmail.com.

Sara A. Vasilenko, Email: sav141@psu.edu.

Stephanie T. Lanza, Email: slanza@psu.edu.

References

- Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Saunders B, De Arellano M, Best C. Assault, PTSD, family substance use, and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:381–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1007772905696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J. Declining alternative reinforcers link depression to young adult smoking. Addiction. 2011;106:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschloo L, van den Brink W, Penninx BW, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Alcohol-use disorder severity predicts first-incidence of depressive disorders. Psychol Med. 2012;42:695–703. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C. Joint trajectories of smoking and depressive mood: Associations with later low perceived self-control and low well-being. J Addict Dis. 2014;33:53–64. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.882717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, O'Grady K, Battjes RJ, Farrell EV. Factors associated with treatment outcomes in an aftercare population. Am J Addict. 2004;13:447–460. doi: 10.1080/10550490490512780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie D, Viner R. ABC of adolescence: Adolescent development. Br Med J. 2005;330:301–304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:890–895. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Maisto SA, Martin CS, Bukstein OG, Salloum IM, Daley DC, Wood DS, Clark DB. Major depression associated with earlier alcohol relapse in treated teens with AUD. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couwenbergh C, Brink W, Zwart K, Vreugdenhill C, van Wijngaarden-Cremers P, van der Gaag RJ. Comorbid psychopathology in adolescents and young adults treated for substance use disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:319–328. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:189–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry JF, Wells KC, Lochman JE, Craighead WE, Nagy PD. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for depressed, substance-abusing adolescents: development and pilot testing. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:656–65. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046861.56865.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Uezato A, Newell JM, Frazier E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:14–18. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Clark DB, Beers SR, Soloff PH, Boring AM, Hall J, Kersh A, Keshavan MS. Hippocampal volume in adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:737–744. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Rose J, Selya A, Piasecki TM, Hedeker D, Mermelstein R. Depression and nicotine dependence from adolescence to young adulthood. Addict Behav. 2015;41:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E. The role of psychiatric disorders in the relationship between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:439–446. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N, Rosand J, Smoller JW. Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:955–964. doi: 10.1002/da.22102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Hemphill SA. Social norms in the development of adolescent substance use: a longitudinal analysis of the International Youth Development Study. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1486–97. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0111-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: ages 14 to 32. Addict Behav. 2015;41:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:481–497. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Zebrak KA, Fothergill KE, Robertson JA, Ensminger ME. Childhood and adolescent risk factors for comorbid depression and substance use disorders in adulthood. Addict Behav. 2012;b37:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Hser Y, Joshi V, Rounds-Bryant J. Drug treatment outcomes for adolescents with comorbid mental and substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:384–392. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerri C, Pascual M. Mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral effects of alcohol consumption during adolescence. Alcohol. 2010;44:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman L, Eccles J. Stage-environment fit during adolescence: trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:522–537. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health: Research Design. 2009 [WWW document] URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Harris KM. Design Features Of Add Health. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Chapel Hill, NC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Kilcoynea B. Comorbidity of psychiatric and substance use disorders in the United States: current issues and findings from the NESARC. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:165–171. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283523dcc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Varying-coefficient models. J Roy Stat Soc. 1993;B55:757–779. [Google Scholar]

- Husky MM, Mazure CM, Paliwal P, McKee SA. Gender differences in the comorbidity of smoking behavior and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Liu X, Li R, Piper ME. Advancing the understanding of craving during smoking cessation attempts: a demonstration of the time-varying effect model. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:S127–134. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Ray LA, Rhee SH, Unger JB. Genetic and environmental influences on the association between depressive symptom dimensions and smoking initiation among Chinese adolescent twins. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:559–568. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion–smoking comorbidity. Psychol Bull. 2015;141:176–212. doi: 10.1037/bul0000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Tan X, Huang L, Wagner A, Yang J. The Methodology Center; Penn State, University Park, PA: 2014. TVEM (Time-varying effect model) SAS macro suite users' guide (Version 2.1.1) Retrieved from http://methodology.psu.edu. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Olsson CA, Jorm AF, Romaniuk H, Patton GC. Association of adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety with daily smoking and nicotine dependence in young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:1652–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, McQueeny T, Nagel BJ, Hanson KL, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. Prefrontal cortex volumes in adolescents with alcohol use disorders: unique gender effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel BJ, Schweinsburg AD, Phan V, Tapert SF. Reduced hippocampal volume among adolescents with alcohol use disorders without psychiatric comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. Br J Psychiat. 2002;325:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TJ, Ma JZ, Crews KM, Li MD. Depressive symptoms among heavy cigarette smokers: the influence of daily rate, gender, and race. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1714–1721. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W. Does cannabis use lead to depression and suicidal behaviours? A population-based longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin C, Hand D, Boudreau B, Santor D. Gender differences in the association between substance use and elevated depressive symptoms in a general adolescent population. Addiction. 2005;100:525–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Sawyer MG, Raphael B, Patton GC, Lynskey MT. The mental health of teenagers who use marijuana. Br J Psychiat. 2002;180:216–221. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Waldron HB, Turner CW, Brody J, Jorgensen J. Sequenced versus coordinated treatment for adolescents with comorbid depressive and substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0035808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL, Liddle HA, Greenbaum PE, Henderson CE. Impact of comorbidity on treatment of adolescent drug abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:129–140. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychol. Methods. 2012;17:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Sutkowi A, Moos R. Patients with dual diagnoses or substance use disorders only: 12-step group participation and 1-year outcomes. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:613–627. doi: 10.3109/10826080903452421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu AW, Ratner PA, Johnson JL. Gender differences in the correlates of adolescents' cannabis use. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1438–1463. doi: 10.1080/10826080802238140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Predictors of multiple sexual partners from adolescence through young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2014;56:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, Piper ME, Lanza ST, Liu X, Yang J, Li R. Time-varying processes involved in smoking lapse in a randomized trial of smoking cessation therapies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:S135–S143. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vourakis C. Admission variables as predictors of completion in an adolescent residential drug treatment program. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2005;18:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2005.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jordan JD, Schroeder KM, Acheson SK, Georgi BD, Sauls G, Ellington RR, Swartzwelder HS. Predictors of relapse during treatment and treatment completion among marijuana-dependent adolescents in an intensive outpatient substance abuse program. Subst Abuse. 2004;25:53–59. doi: 10.1300/J465v25n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesbeck GA, Kuhl HC, Yaldizli O, Wurst FM. Tobacco smoking and depression--results from the WHO/ISBRA study. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57:26–31. doi: 10.1159/000123119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Wedgwood L, Niven H, Kay-Lambkin F. Smoking cessation and depression: current knowledge and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:97–107. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, Zvolensky M, Adler LE, Audrain-McGovern J, Breslau N, Brown RA, George TP, Williams J, Calhoun PS, Riley WT. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]