Abstract

Objectives

Indigenous Australians have a disproportionately high burden of chronic illness, and relatively poor access to healthcare. This paper examines how a national multicomponent programme aimed at improving prevention and management of chronic disease among Australian Indigenous people addressed various dimensions of access.

Design

Data from a place-based, mixed-methods formative evaluation were analysed against a framework that defines supply and demand-side dimensions to access. The evaluation included 24 geographically bounded ‘sentinel sites’ that included a range of primary care service organisations. It drew on administrative data on service utilisation, focus group and interview data on community members’ and service providers’ perceptions of chronic illness care between 2010 and 2013.

Setting

Urban, regional and remote areas of Australia that have relatively large Indigenous populations.

Participants

670 community members participated in focus groups; 374 practitioners and representatives of regional primary care support organisations participated in in-depth interviews.

Results

The programme largely addressed supply-side dimensions of access with less focus or impact on demand-side dimensions. Application of the access framework highlighted the complex inter-relationships between dimensions of access. Key ongoing challenges are achieving population coverage through a national programme, reaching high-need groups and ensuring provision of ongoing care.

Conclusions

Strategies to improve access to chronic illness care for this population need to be tailored to local circumstances and address the range of dimensions of access on both the demand and supply sides. These findings highlight the importance of flexibility in national programme guidelines to support locally determined strategies.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Mixed-methods approach, with a large number and diverse range of interviewees, and long-term repeated engagement with stakeholders, including feedback and member checking of data and interpretation.

Wide geographic scope and diversity of study sites, reflecting a broad range of sites with relatively early and intense investment, but not necessarily representative of service settings across Australia.

Use of a widely cited framework to gain a broad understanding across various dimensions of access to care, with sensitivity to the possibility of the access framework being overly Western-centric.

Introduction

Minority groups around the world experience profound barriers to accessing healthcare,1 including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia (respectfully referred to hereafter as Indigenous Australians). Similar to Indigenous populations of other colonised countries, chronic disease contributes to two-thirds of the health gap between Indigenous and other Australians,1–3 with the requirements of good quality chronic illness care making access to such care especially difficult.1 3–7

Recently a number of Australian Government policy initiatives have been directed at addressing access and improving care for Indigenous Australians, including the unprecedented funding of $A805.5 million for the multifaceted Indigenous Chronic Disease Package (ICDP) from 2009 to 2013.8–10 However, there is a general lack of research into, and evaluations of, interventions that aim to improve access to healthcare on which such interventions can be based.4 7 11

Defining access to healthcare

Internationally, there is ongoing debate about how to define access to healthcare and the factors that influence access.11–13 A recent review defined access as ‘the opportunity to have healthcare needs fulfilled’.11 Various authors point to access being reliant on how well healthcare resources (supply side) interact with a patient's ability to seek and obtain care (demand side).4 11–15

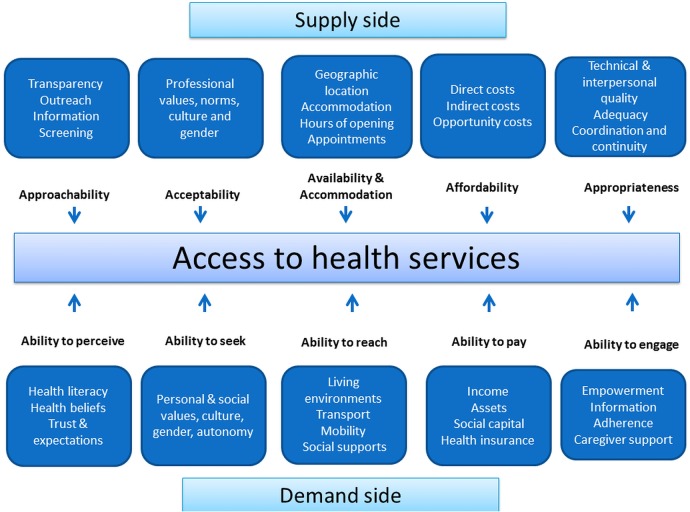

Levesque et al recently proposed a framework where access is achieved through interaction between five corresponding dimensions identified on the supply (service providers) and demand (service seeking) sides (figure 1). It is the interactions between patients and providers that enable access. This comprehensive conceptualisation of access is consistent with recent literature emphasising the need to take an ecological approach to Indigenous health16 and a people-centred approach to healthcare.17

Figure 1.

Adapted conceptual framework of access to health care.11

Delivery of primary healthcare to Indigenous Australians—the Australian context

Inequitable access to healthcare for Indigenous Australians occurs despite access to a universal health insurance scheme, Medicare.3 5 18 Indigenous peoples access primary healthcare (PHC) through private general practice and services specifically established to meet the needs of Indigenous Australians—both community-controlled health services and government-managed Indigenous-specific services (here referred to as Indigenous Health Services).3 19 Access barriers to PHC by Indigenous Australians include economic considerations, transport, cultural attitudes or beliefs, language and communication barriers, the cultural appropriateness of services and paucity of Indigenous staff.5 7 8 19 20

Intervention to improve access for Indigenous Australians to PHC

The ICDP was a national intervention implemented through regional PHC support organisations such as Medicare Locals, private general practices, and Indigenous Health Services.8–10 The ICDP included mainstream services that in many cases have not been proactive in providing PHC to Indigenous Australians. This is an important issue, as not all Indigenous Australians are able, or choose, to access Indigenous-specific services.20 A key aim of the ICDP was to improve access to PHC, and funding was provided for a new workforce to enhance the capacity of PHC services to more effectively prevent and manage chronic disease (table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the indigenous chronic disease package

| Priority area: tackling chronic disease risk factors | Priority area: improving chronic disease management | Priority area: workforce expansion and support |

|---|---|---|

Measures/strategies to:

|

Measures/strategies to:

|

Measures/strategies to:

|

Source: Department of Health, 2010.

This paper assists in addressing the gap in research and evaluation of interventions to improve access to healthcare through providing an analysis of the ICDP against a framework that defines various dimensions of access.11 We describe how aspects of the ICDP have been operationalised in relation to improving access to chronic illness care, and identify key gaps in how determinants of access have been addressed.

Methods

We draw on the mixed-methods Sentinel Sites Evaluation (SSE) of the ICDP—methods are described in detail elsewhere.8 In summary, the SSE was a multisite, place-based, formative evaluation spanning 24 urban, regional and remote locations in all Australian States and Territories. The evaluation was intended to inform ongoing implementation of the ICDP. Sites were selected where there was early and relatively intense ICDP investment. Data were collected, analysed and reported in six monthly intervals over five evaluation cycles between 2010 and 2013.

Administrative data

Administrative billing data on uptake of specific government subsidised items of healthcare (Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) Co-payment, Practice Incentives Program (PIP) Indigenous Health Incentive (PIP-IHI) and health assessments billing data) were provided by the Commonwealth Government Department of Health from May 2009 to May 2012. The PBS Co-payment and PIP-IHI were introduced in May 2010. May 2009 to April 2010 was used as a ‘baseline’ period for health assessments, which were introduced before the ICDP.

Data are presented as uptake per 100 Indigenous Australians aged 15 years or over. Population data are based on Australian Bureau of Statistics projections from the 2006 Census according to the statistical boundaries used to define the sites.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data on access to healthcare were obtained from community focus groups and semistructured individual or group interviews with a range of key informants from Indigenous Health Services and the private general practice sector—including employees of Medicare Locals (table 2). Key informants were purposively sampled for their knowledge and experience with the ICDP, and included general practitioners, nursing staff, practice managers, ICDP workforce such as Outreach Workers (OWs), programme managers, management staff and pharmacists. Most ICDP workers were members of local Indigenous communities and could speak from the perspective of consumers of healthcare as well as from the perspective of health workers.

Table 2.

Individual interview participant characteristics by interview type, rurality, sector and position; community focus group characteristics by rurality and gender

| Urban | Regional | Remote | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | ||||

| Participants* | 138 | 157 | 79 | 374 |

| Individual interview | 123 | 108 | 65 | 296 |

| Individuals participating in a group interview | 15 | 49 | 14 | 78 |

| Sector† | ||||

| Indigenous health | 67 | 64 | 55 | 186 |

| General practice | 56 | 74 | 20 | 150 |

| Position | ||||

| Clinician (GP) | 32 (21) | 37 (14) | 19 (8) | 88 (43) |

| Managers | 35 | 42 | 30 | 107 |

| Practice managers | 13 | 23 | 7 | 43 |

| ICDP-funded workforce | 43 | 35 | 19 | 97 |

| Pharmacist | 15 | 20 | 4 | 39 |

| Community focus groups | ||||

| Participants | 261 | 259 | 150 | 670 (31% male; 69% female) |

Indigenous health sector includes: Indigenous Health Services and National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation State and Territory Affiliates.

General practice sector includes: general practice, Medicare locals, divisions of general practice, state-based organisations.

Manager category includes interviews with programme managers, programme officers and CEOs.

ICDP-funded category includes interviews with ICDP-funded positions such as Indigenous Health Project Officer, Care Coordinator and Outreach Worker.

Clinician category includes interviews with GPs, nurses, Aboriginal health workers and allied health professionals.

*Interviewees may have been interviewed more than once throughout the evaluation period. This represents the number of individuals interviewed or contributed to a group session at least once during the evaluation period.

†Sector numbers do not add up with the interview numbers as it excludes pharmacists not employed by Indigenous Health Service and workforce agency interviews.

CEO, chief executive officer; ICDP, Indigenous Chronic Disease Package; GP, general practitioner.

Community focus groups explored consumer and community perceptions of change in accessibility and quality of services, and the extent to which any change may have been due to the ICDP. Key stakeholder organisations such as the local Indigenous Health Service assisted with convening these groups and identifying participants who met recruitment criteria (member of the local Indigenous community, at risk of or have a chronic conditions, experience using health services in the site). Group interviews with providers and community focus groups were conducted by a trained facilitator and an observer from the SSE team to support equitable input by participants. Repeated six monthly cycles of interviews, focus groups and feedback of data between November 2010 and December 2012 allowed review and refinement of our understanding of issues in accessing chronic illness care services.

Data analysis

We analysed the SSE qualitative data using a conceptual framework of access to healthcare (figure 1).11 Data analysis and extraction were iterative. During the initial analysis of the SSE data, the lead author (JB) coded the primary data in NVIVO V.9,21 with specific coding of access from a broad perspective. The data were then further coded in relation to the specific dimensions of supply and demand-side determinants of access relevant to the framework (figure 1)11 and by ICDP measures (table 1).

In order to ensure the reliability of results, three authors (JB, AL, TM) individually reviewed and then conferred on the categorisation. Any differences in categorisation or perceptions of the relevance were discussed and resolved. In the final stage of analysis, the same three authors (JB, AL, TM) reviewed the full SSE Final Report8 in order to identify any additional information relating to access. This information was reviewed and where relevant was also categorised within the access framework. Emergent themes not encompassed in the Levesque framework were also identified through this iterative process. For each dimension, we considered the ways in which the ICDP influenced (or failed to influence) the fit between the features of the health service, and features of communities and people with or at risk of chronic disease, to improve access.

All authors checked if the results were consistent with their perceptions and understanding, based on their experience as SSE team members. Only minor adjustments were required to achieve good concordance between authors in the categorisation, analysis and interpretation of the data.

This paper focuses on those aspects of the ICDP that were strongly orientated to improving access to health services (rather than detailing all aspects with any relevance to access). The identified dimensions to access were not independent of each other; some findings were relevant to more than one access dimension. We have therefore described the ICDP programmes of work according to the predominant dimension of access and the most important influence.

Results

In total, 374 key informants participated in individual or group interviews, many in multiple evaluation cycles that aimed to assess changes in perceptions and experiences over time (table 2). Interviewees represented a broad cross-section of health service sectors, settings and roles, including clinicians, ICDP-funded workforce, programme managers and practice managers from the general practice and Indigenous health sector across urban, regional and remote locations. The 72 community focus groups involved 670 participants from urban, regional and remote settings (table 2).

Implementation of the ICDP was slower than anticipated, but health services, particularly those with a history of providing PHC to Indigenous people, welcomed the availability of resources to improve services.

Quantitative measures

Uptake of the PIP-IHI, PBS Co-payment and health assessments were a result of a combination of determinants of access working simultaneously. There was wide variation between urban, regional and remote sites but more variation at the site level. Since both ‘quantity’ and ‘quality’ are important, caution should be used when considering quantitative measures of uptake alone as measures of success.

PIP Indigenous health initiative

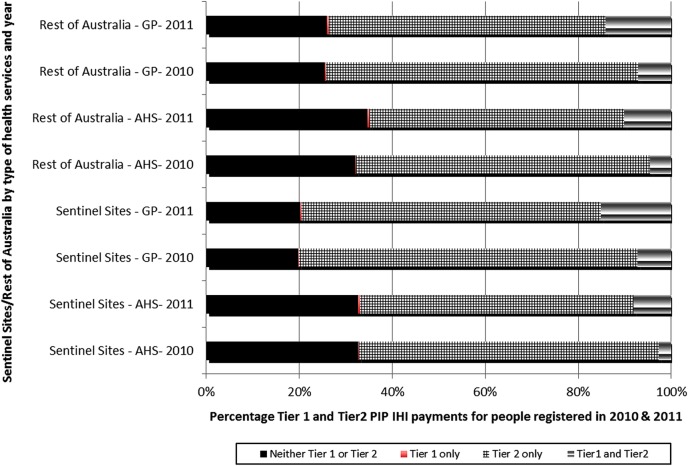

The PIP-IHI was intended to bring about systematic changes in service delivery such as encouraging improvements in chronic illness care, enhancing capacity, access and health outcomes for patients through culturally appropriate and coordinated care (table 1). The number of health services registered with the PIP-IHI per 1000 people is to some extent an indicator of accessibility, or at least provider choice for Indigenous people. By November 2011, 40% of health services registered for the incentive had not yet registered patients; many general practices had few or no Indigenous patients.

Patients registered for the PIP-IHI were expected to have a diagnosed chronic disease; therefore, it is notable that additional payments reflecting continuity of care and planned review (tier 1 or 2 payments) were not triggered for around 30% of patients (figure 2). This indicates a substantial proportion of patients registered for the PIP-IHI were not attending health services regularly, or health services were not billing for care in a way that triggered payments. There was a higher percentage of PIP-IHI registered patients for whom no payments were made in Indigenous Health Services than in the general practice sector.

Figure 2.

Percentage of tiers 1 and 2 payments for people registered for the PIP Indigenous Health Incentive for sentinel sites and the rest of Australia, by sector and year 2010–2011. GP, general practice; AHS, Aboriginal Health Service; PIP-IHI, Practice Incentives Program Indigenous Health Incentive.

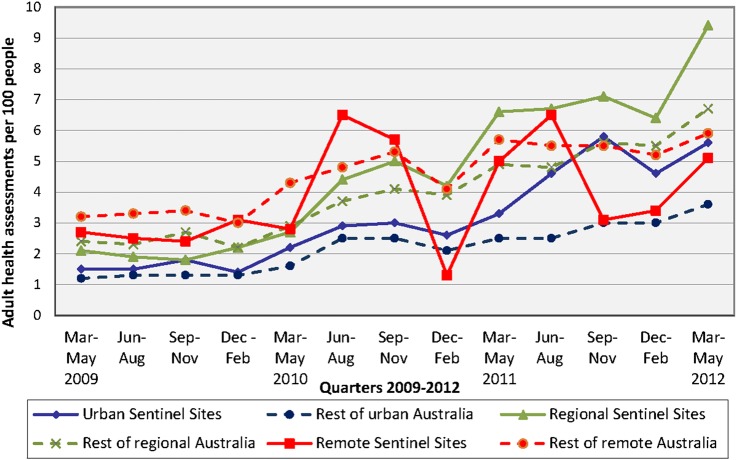

Indigenous-specific health assessments

Uptake of health assessments (which are primarily preventive and diagnostic) increased almost fourfold over the evaluation period in the sentinel sites, and around twofold in the rest of Australia (figure 3). This may reflect increased autonomy and knowledge about healthcare options, and greater ‘ability to seek care’ and ‘acceptability’.

Figure 3.

Adult health assessments (Medicare Benefits Schedule items 704, 706, 710 to 1 May 2010 thereafter 715) claimed per 100 Indigenous people aged ≥15 years in sentinel sites and the rest of Australia, by quarter and rurality, March 2009 to May 2012.

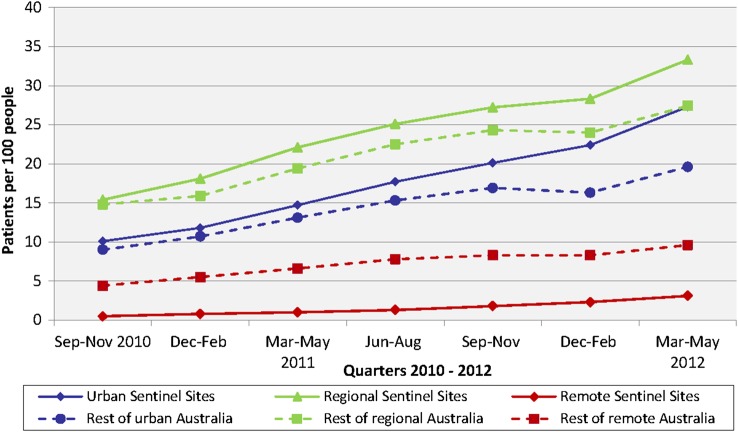

PBS copayment

The PBS Co-payment initiative provided subsidised or free prescription medicines. It worked as a patient incentive to access other health services offered as part of the ICDP, and, as reported in the interviews and community focus groups, resulted in improved medication adherence. Uptake was higher than expected (27 per 100 eligible Indigenous patients across the evaluation sites in March to May 2012) and was promoted by the ICDP workforce (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of Indigenous people accessing the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) Co-payment measure per 100 Indigenous people aged ≥15 years for sentinel sites and the rest of Australia, by rurality, quarter, September 2010 to May 2012.

ICDP programmes of work according to the predominant dimension of access and the most important influence.

Findings are presented according to the corresponding dimensions of access proposed by Levesque et al.11 Example quotes to illustrate the findings are presented in table 3. Online supplementary table S1 details an assessment of all of the ICDP measures against the framework.

Table 3.

Dimensions of access framework (as per the Levesque framework,11 with illustrative quotes

| Dimensions of access11 | Example quotes |

|---|---|

| ‘Approachability’ and ‘ability to perceive’ |

The IHPO and OW have been very active in community engagement and letting community know about the initiatives available at health services. They have done this by attending lots of community events and Aboriginal organisations. (Group discussion, regional site) [OW name] also does one-on-one ‘yarn’ with patients when waiting at Doctor's or in the car or in any other appointments about their health issues and gives them some options to think about their change. The direct assistance to patients attending appointment helps in maintaining regular attendance at the health services (IHPO, urban site) |

| ‘Acceptability’ and ‘ability to seek’ |

IHPO and OW have assisted with cultural awareness. Staff now ask all clients if they are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and not questioning Aboriginality or ‘looking at the colour…sometimes they may be white’ (Practice nurse, urban site) ‘The OW knows the Aboriginal people and ways of networking with the community, they can go into their house and get around them in certain ways…their communications are good they know how to communicate with the Aboriginal community and with Aboriginal people (Practice nurse, general practice, regional site) |

| ‘Availability and accommodation’ and ‘ability to reach’ |

The community often have no fixed address, no phone or changing numbers or no credit card, so the outreach worker [will] go and find that person and get them (General Practitioner, remote site) [The OW] will even bring the patients down for us. If there is a new person in the area that wants to see a doctor they will bring them down to the surgery…If I say I have got a patient I have been trying to get a hold of and can't get them [the OW] will even try for me too and with their contacts they know a lot of the family groups and they [are able to] help out (Practice nurse, urban site) |

| ‘Affordability’ and ‘ability to pay’ |

There has been increased attendance at [name of health service] as patients coming back for medications as they know they can afford them (General Practitioner, regional site) Too expensive to see a doctor [specialist], costs about $90, that's a lot of money, a lot of doctors want the money up front and some do bulk bill, some don't. Some say they are booked out and don't take on any more patients around town (Community focus group, regional site) |

| ‘Appropriateness’ and ‘ability to engage’ |

We have patients with a lot of chronic diseases who live a bit far away. [Name of OW] has been fantastic to coordinate all appointments and actually transporting patients to make sure the appointments are attended (General Practitioner, regional site) We have linked community members with services and facilitated client access, patient registration for PIP Indigenous Health Incentive and provided client follow-up services. We have helped develop relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and staff within various mainstream general practices. This has resulted in staff and clients being more comfortable talking to each other which then results in clients attending the services more often and more regularly (Outreach Worker, urban site) |

IHPO, Indigenous Health Project Officer; OW, Outreach Worker; PIP, Practice Incentives Program.

‘Approachability’ and ‘ability to perceive’

The ICDP enhanced interactions between health service ‘approachability’ and the corresponding abilities of communities and individuals to ‘perceive the need for care’. A strong focus on improving the ‘approachability’ of health services ensured that services could be identified by health service providers and Indigenous Australians.

Services offered by Indigenous Health Services tended to be known in Indigenous communities prior to the ICDP; therefore, it had a limited role in promoting community awareness about existing services. Several new and expanded services became available through the ICDP (the availability of subsidised or free medications, nicotine patches to support smoking cessation and increased availability of health assessments). Interviewees consistently highlighted the role of the ICDP workforce in promoting these new services to communities; community perception of the benefit of a new service item also played a role in uptake. Indigenous Health Project Officers (IHPO) in particular appeared to bridge gaps between communities and services not specifically set up to meet Indigenous community needs. Employed in Medicare Locals, IHPO strategies included developing and distributing lists of participating general practices—including those providing services at no direct cost to patients. Tensions over whether IHPOs should focus on supporting health services to improve approachability, or on increasing community knowledge of the need and ways to access services were overcome by adapting approaches according to local contexts. IHPOs identified as Indigenous tended to work more at a community level. Community focus groups indicated that negative past experiences of accessing care negatively influenced people's willingness to seek care. OWs acted as cultural brokers to support positive healthcare encounters and build trust.

In some sites, the ICDP workforce provided health services with information about other services to which they could confidently refer Indigenous patients.

Programme design had conceived OW positions as entry-level positions, intending they would be recruited from local communities, thus improving the ‘fit’ between health services and clients. However, resources for OW positions were utilised differently in different contexts; some health providers recruited qualified and experienced health professionals, concerned that the OW role involved supporting and transporting people with complex medical problems. A further consideration with policy and funding implications is that experienced practitioners give credibility to programmes in communities.

‘Acceptability’ and ‘ability to seek’

Interaction between ‘acceptability’ of the service and ‘ability of individuals to seek care’ was enhanced through the ICDP. Cultural awareness of general practices and related support organisations improved through organising and/or delivering cultural awareness training. Health service staff valued one-on-one interactions with OWs, which often focused on creating welcoming reception areas using Indigenous art and targeted reading matter. Community focus groups reported positive changes in service delivery as a result of general practice staff attending cultural awareness training, changes not seen to be required in Indigenous Health Services (already established as culturally appropriate services). Despite cultural awareness training, some community focus groups reported perceptions and experiences of racism when accessing some services, particularly in specialist reception rooms and pharmacies. These staff were not targeted for cultural awareness training.

The cultural brokerage role of Indigenous people employed in OW positions made services more ‘acceptable’ and assisted with access to care, providing a fit between ‘acceptability’ and ‘ability to seek’.

Prior to the ICDP, many general practices and Indigenous Health Services did not have systematic approaches to identify which of their patients were Indigenous. ICDP-funded staff worked with general practices to increase identification of Indigenous patients.

In some instances, services employed people in male and female OW roles to ensure gender sensitivity—an important cultural consideration. Some health services offered gender-specific health assessment days. In making services more culturally safe and therefore more accessible, these initiatives contributed to the ‘ability of people to seek care’.

‘Availability and accommodation’ and ‘ability to reach’

The ICDP enhanced interactions between ‘availability and accommodation’—health services being physically reachable—and the dimension ‘ability to reach’, by improving patient access to transport, outreach services and establishing additional specialised clinics.

Outreach services (specialist and allied health) were established in underserviced areas (table 1)—‘availability and accommodation’—resulting in improved access in some sites. However, low numbers of referrals and low patient attendance for many services raised questions about efficiency, and impacted on specialist retention. Capacity of host organisations (predominantly Indigenous Health Services) to manage clinics, coordinate visits, utilise recall and reminder systems, and arrange patient transport influenced attendance at appointments. Improved communication was needed to inform general practices about availability of outreach services.

Despite this investment, challenges to accessing specialist care persisted, especially for patients in small, dispersed communities, and for services contacting patients who did not have a fixed address or a mobile telephone. OWs supported contact in these circumstances.

Lack of transport to attend appointments was consistently identified as a barrier in accessing care—‘the ability to reach’. OWs played key enabling roles, including arranging transport and driving patients to appointments where vehicles (not funded through the ICDP) were available.

There were limited efforts to improve social supports, as highlighted in the framework under ‘ability to reach’. Efforts comprised of OWs linking patients to support services such as housing, recognising the need to offer support in addressing broader determinants of health and other priorities in their clients’ lives. This was reported by OWs as time-consuming and not always recognised or supported as a core part of their role.

‘Affordability’ and ‘ability to pay’

Several ICDP components were intended to reduce the cost of healthcare. ICDP workforce actively advocated for the removal of cost barriers; for example, advocating for care providers to charge fees equal to government subsidies, so patients would not incur personal costs.

ICDP-funded specialist outreach programmes were designed to be free of cost to patients. Funding was also available for medical aides and transport to a subset of clients through Care Coordinators and a ‘supplementary services’ programme (used in some sites to pay the fee differential between the government subsidy and charges by private providers). Despite these investments to address affordability, community focus groups raised concerns about the costs of consulting private specialists in particular. Private specialists sometimes ordered tests that patients were unable to pay for, and ICDP-funded specialists referred patients to private providers for further tests. Ability to pay was an enduring concern.

Activities to encourage healthy eating and exercise classes targeting Indigenous people were provided at no cost to participants. The reach of activities at a population level was variable, with those most in need not necessarily having access.

Despite the positive response to the removal of medication cost barriers through the PBS Co-payment measure, financial barriers continued to influence access to medication in particular circumstances. These included when eligible patients were prescribed medication by doctors employed in hospitals (therefore not ICDP registered); attended general practices not participating in the ICDP; and encountered pharmacy staff who were not aware of the strategy. Specialists were initially unable to prescribe under the scheme; however, this changed during ICDP implementation.

‘Appropriateness’ and ‘ability to engage’

Improving coordination and continuity—‘appropriateness’—were ICDP aims. The PIP-IHI was designed to improve the fit between chronic illness care services and Indigenous population needs. The concept of a ‘medical home’—a regular health service—for patients was encouraged but not fully realised, probably due to a focus on registering eligible people to enable immediate access to benefits, rather than on determining the most appropriate or convenient practice to provide and receive ongoing care. There was also a lack of follow-up after a health assessment.22 Effective chronic illness management involves coordination and continuity of care, and engagement by patients; therefore, the possible lack of ongoing attendance was concerning.

As outlined in ‘ability to pay’, patient attendance and adherence to medication improved with the removal of cost barriers to medication. This ‘ability to pay’ enabled an ‘ability to engage’—patients felt they could fill prescriptions and avoid the shame of being unable to afford prescribed medications.

Barriers to appropriate care continued despite utilisation of care and contact with providers. The lack of both follow-up after health assessments22 and continued cycles of care through the PIP-IHI suggests inconsistent levels of care after initial contact with the health service.

In some instances, delivery of health assessments by services appeared to be driven by a business imperative (as delivery attracted a government payment), with little evidence that patients and communities perceived the need for these checks. This is relevant to the access dimension ‘ability to perceive’—patients may want a health assessment if their understanding of health risk factors is increased.

Despite multifaceted strategies to improve access to chronic illness care, data showed minimal evidence of systematic processes being applied to ensure that most vulnerable, for example, those with the least formal education and financially poorest were benefiting from the ICDP. There was an opportunity to improve population coverage generally and direct activities and resources to target population subgroups most in need. The ICDP workforce often had responsibility for covering large populations or geographic areas, with limited capacity to reach those who might benefit most from the programme.

Discussion

There is considerable evidence that the ICDP resulted in improved access to chronic illness prevention and management. Qualitative evidence indicated an increase in access related to ICDP activities such as the removal of cost barriers to medicines; removal of transport barriers to attend services; improved cultural safety in general practices; support and assistance from ICDP workforce for Indigenous people to access healthcare services; and more community programmes/resources to support healthy lifestyle choices and health-seeking behaviours. While quantitative evidence also showed more Indigenous Australians were registering for the PIP-IHI, having health assessments and obtaining subsidised prescription medications through a PBS Co-payment, it is not clear to what extent these data reflect an actual increase in access to high-quality PHC services. They may reflect greater recording of access to these services.

On the whole, the removal of cost barriers and the creation of welcoming, culturally safe spaces appeared to make the greatest contribution to increased access to chronic illness prevention and management services by Indigenous people. Use of the access framework for analysis shows how the ICDP focused predominantly on supply-side aspects to improving access to healthcare. This is consistent with literature, which suggests that internationally there is a focus on supply-side aspects to access rather than demand side.4 11 The ICDP mostly targeted service providers and to a lesser extent, patients. Continued work is needed to address the demand-side dimensions to access, together with ongoing strategies to address supply-side dimensions. Influencing behaviour of Indigenous people in seeking healthcare will in part rely on ongoing social reforms to address social and other determinants of health and access to care.4 23

The use of this access framework for analysis highlighted a gap in the ICDP implementation—a lack of complementary programmes in relevant sectors other than health and insufficient attention to social determinants of health, through programmes to address people's ‘ability to pay’ by addressing social and economic disadvantage. Work was being undertaken through other Commonwealth-funded programmes to address issues in housing and education, for example, but there were no clear or explicit linkages with the ICDP and, on the ground, insufficient understanding by service providers that some ICDP workforce roles required a more holistic approach.

While the access framework11 has been well cited,13 23–26 we have been unable to identify any previous work where it has been used to analyse how well programmes have addressed access—as we have done in this paper. We found the access framework11 useful for analysing access across various dimensions and identifying gaps in ICDP investment or implementation. However, the original presentation of the access framework11 is vague on the extent to which dimensions are expected to be discrete, and the extent to which demand-side and supply-side ‘pairs’ are expected to directly correspond with each other. In applying this framework for our analysis, we found that the dimensions of access are not discrete, and in some instances it was difficult to clearly align ICDP-related activities with specific dimensions. In many cases, activities related to more than one dimension. The strong links and inter-relationships between themes needed to be recognised when interpreting the data—in some instances, themes related to other dimensions rather than the directly corresponding pair.

The framework is presented as a ‘pathway of utilisation’ from perception of need to healthcare utilisation. It is not clear if the dimensions are expected to reflect points along a continuum. Our analysis of data suggests the different dimensions may be relevant to a number of points along the ‘pathway of utilisation’.

There was wide variation in uptake of the ICDP at the local site level. Local context influences the implementation of health interventions, and also affects the relative importance of each dimension and the interaction between different dimensions. For example, in some sites, there was a perceived need to focus more on approachability of the health service than on affordability.

Barriers to access identified in our analysis are consistent with research on barriers to healthcare for Indigenous Australians.5 18 21 27 Key emerging challenges include achieving general population coverage and reaching high-need groups. The diversity of contexts in which PHC services operate, the wide variation in uptake of the ICDP between sites, and the relevance of different contextual factors to barriers to access, mean that strategies will need to be tailored to local circumstances and address all aspects of access on both the demand and supply sides. ICDP workforce role definitions and guidelines may be better served by building more flexibility into the role definition for local adaptation.

Strengths of the analysis include the mixed-methods approach, the number and diversity of interviewees, the geographic scope and diversity of study sites, and long-term repeated engagement with stakeholders, including feedback and member checking of data and interpretation. More general limitations of the SSE have been described elsewhere,8 and include the selection of sites on the basis of early and relatively intense ICDP investment and selection of interviewees based on their knowledge and interest in Indigenous health. The data provide a broad perspective of service settings across Australia, but this perspective may not necessarily be representative of PHC settings in general. We were aware in the analysis process that categorisation of themes into the analytical framework may be overly Western-centric,28 and endeavoured to limit this through an iterative review process involving Indigenous team members.

Improving access to PHC for marginalised and vulnerable populations is a complex challenge, requiring multifaceted solutions. This paper teases out some of these complexities, and the findings are relevant to policymakers developing programmes that intend to improve access to healthcare for at-risk populations. Our findings reinforce the need to consider the range of determinants that may need to be addressed, increased efforts to engage Indigenous community members and to ensure appropriate care is continued beyond initial contact with the health service in order to improve access to health services.

Conclusions

This major government-funded package of interventions has had some success in overcoming barriers to accessing healthcare by supplying services that are more approachable, acceptable and affordable for Indigenous Australians. There is now a need to confront important challenges to address demand-side dimensions of access that have not been adequately addressed, such as ‘ability to pay’. Changing the way services are sought by Indigenous Australians will rely in part on ongoing social reforms to address social and other determinants of health and access to care.

Acknowledgments

The Sentinel Sites Evaluation was conceived and funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Successful conduct of the evaluation was made possible through the active support and commitment of key stakeholder organisations, community members, individuals who participated in the evaluation, and the contributions made by the broader evaluation team and the Department staff. RB is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship (#FT100 100 087).

Footnotes

Contributors: JB played the lead role in the conceptualisation, data analysis, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript—with support from RB and GS. MK contributed to the conceptualisation of the paper, and conducted the analysis for the administrative data. All authors contributed to refinement of the paper, based on their close involvement with the evaluation, and all approved the final manuscript. RB led the overall Sentinel Sites Evaluation.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The Sentinel Sites Evaluation was conducted by Menzies School of Health Research under contract to the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the SSE was granted through the Commonwealth Government Department of Health Ethics Committee, project number 10/2012.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ring I, Brown N. The health status of indigenous peoples and others: the gap is narrowing in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand, but a lot more is needed. BMJ 2003;327:404 10.1136/bmj.327.7412.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Contribution of chronic disease to the gap in adult mortality between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australians. Cat.No.IHW48 Canberra: AIHW, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2014—in brief. Cat.No.AUS181 Canberra: AIHW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comino E, Davies G, Krastev Y et al. . A systematic review of interventions to enhance access to best practice primary healthcare for chronic disease management, prevention and episodic care. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:415 10.1186/1472-6963-12-415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Medical Association. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health report card 2010-11: best practice in primary health care for Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders. Canberra: Australian Medical Association, 2011.

- 6.Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2012 Report Canberra: AHMAC, 2102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware VA. Improving the accessibility of health services in urban and regional settings for Indigenous people. Resource sheet no. 27. Produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Melbourne, Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailie R, Griffin J, Kelaher M et al. . Sentinel Sites Evaluation: final report. Prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Canberra: Menzies School of Health Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health. Closing the gap information for General Practice, Aboriginal community-controlled health services and Indigenous health services. Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health [website]. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/irhd-chronic-disease (accessed 24 Jan 2015).

- 11.Levesque J, Harris M, Russell G. Patient-centred access to healthcare: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:18 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver A, Mossialos E. Equity of access to health care: outlining the foundations for action. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:655–8. 10.1136/jech.2003.017731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edusei J, Amoah P. Appreciating the complexities in accessing health care among urban poor: the case of street children in Kumasi Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Dev Country Stud 2014; 4:69–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frenk J. The concept and measurement of accessibility. In: White KL, Frenk J, Ordonez C, Paganini JM, Starfield B, eds, et al. Health services research: an anthology. Washington: Pan American Health Organization, 1992:858–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooney G. Equity in health care: confronting the confusion. Eff Health Care 1983;1:179–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arabena K. Future initiatives to improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Med J Aust 2013;199:22–22. 10.5694/mja13.10816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirzaei M, Aspin C, Essue B et al. . A patient-centred approach to health service delivery: improving health outcomes for people with chronic illness. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:251 10.1186/1472-6963-13-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Access to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cat.No.IHW46 Canberra: AIHW, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baba JT, Brolan CE, Hill PS. Aboriginal medical services cure more than illness: a qualitative study of how Indigenous services address the health impacts of discrimination in Brisbane communities. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:56 10.1186/1475-9276-13-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayman N, White N, Spurling G. Improving Indigenous patients access to mainstream health services: the Inala experience. Med J Aust 2009;190:640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012.

- 22.Bailie J, Schierhout G, Kelaher M et al. . Follow-up of Indigenous-specific health assessments-a socioecological analysis. Med J Aust 2014;200:653–7. 10.5694/mja13.00256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward B, Humphreys J, McGrail M et al. . Which dimensions of access are most important when rural residents decide to visit a general practitioner for non-emergency care? Aust Health Rev 2015;39:121–6. 10.1071/AH14030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duckett S, Breadon P, Ginnivan L. Access all areas: new solutions for GP shortages in rural Australia. Melbourne: Grattan Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breton M, Brousselle A, Boivin A et al. . Evaluation of the implementation of centralized waiting lists for patients without a family physician and their effects across the province of Quebec. Implement Sci 2014;9:117 10.1186/s13012-014-0117-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westlake C, Sethares K, Davidson P. How can health literacy influence outcomes in heart failure patients? Mechanisms and interventions. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2013;10:232–43. 10.1007/s11897-013-0147-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau P, Pyett P, Burchill M et al. . Factors influencing access to urban general practices and primary health care by Aboriginal Australians-a qualitative study. Alternative 2012;8:66–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston L, Doyle J, Morgan B et al. . A review of programs that targeted environmental determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:3518–42. 10.3390/ijerph10083518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]