Abstract

Objective

Dietary supplement use has increased over past decades, resulting in reports of potentially serious adverse events. The aim of this study was to develop optimised methods to evaluate the causal relationships between adverse events and dietary supplements, and to test these methods using case reports.

Design

Causal relationship assessment using prospectively collected data.

Setting and participants

4 dietary supplement experts, 4 pharmacists and 11 registered dietitians (5 men and 14 women) examined 200 case reports of suspected adverse events using the modified Naranjo scale and the modified Food and Drug Administration (FDA) algorithm.

Primary outcome measures

The distribution of evaluation results was analysed and inter-rater reliability was evaluated for the two modified methods employed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and Fleiss’ κ.

Results

Using these two methods, most of the 200 case reports were categorised as ‘lack of information’ or ‘possible’ adverse events. Inter-rater reliability among entire assessors ratings for the two modified methods, based on ICC and Fleiss’ κ, were classified as more than substantial (modified Naranjo scale: ICC (95% CI) 0.873 (0.850 to 0.895); Fleiss’ κ (95% CI) 0.615 (0.615 to 0.615). Modified FDA algorithm: Fleiss’ κ (95% CI) 0.622 (0.622 to 0.622).

Conclusions

These methods may help to assess the causal relationships between adverse events and dietary supplements. By conducting additional studies of these methods in different populations, researchers can expand the possibilities for the application of our methods.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, NUTRITION & DIETETICS, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There is no optimised method for evaluating these adverse events.

We developed two methods for assessing adverse events associated with dietary supplements and inter-rater reliability among entire assessors was classified as more than substantial.

Our methods may be useful for assessing adverse events caused by dietary supplements in clinical settings.

This simple and easy method for evaluating causal relationships can contribute to prompt issue evaluation, signal detection and regulatory updating.

Additional studies with different populations are needed to expand the possibilities for application of our methods.

Introduction

The entire functional food market is estimated to be worth over US$80 billion.1 This market reached US$32.5 billion in the USA in 2012,2 with more than half of the adults reporting use of one or more dietary supplements. Sales of dietary supplements have also increased in Japan, with an estimated market size second only to that of the USA.1 In fact, one study indicated that over 50% of the Japanese population consumes dietary supplements.3 With the increased use of dietary supplements, a number of adverse events have been reported.4–8 Some of these adverse events can lead to severe disability or death, so managing risk and safety is essential in order to protect consumers. Several legal systems have been developed to regulate labelling and manufacturing standards for dietary supplements, but there are no clear systems in place to detect and report adverse events.9–11

Evaluation of the causality of adverse events is essential in order to determine the risk and safety of supplements. It can also help with issue evaluation, signal detection and regulatory updating. Several methods exist for evaluating causality, including the Naranjo scale,12 13 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) algorithm,14–16 the Kramer scale,13 17 the Liverpool scale18 and the WHO scale.19 However, these methods are primarily used to assess adverse events associated with medications. They are not optimised for application to dietary supplements. The information available from consumers taking dietary supplements differs from information provided by patients taking medications. Therefore, the development and optimisation of methods to evaluate the causal relationship between adverse events and dietary supplements is essential in order to improve the quality of risk management.

In the present study, we modified the Naranjo scale and the FDA algorithm and then used these to assess 200 case reports of suspected adverse reactions to dietary supplements. The main objective of this study was to test these modified methods using case reports.

Methods

Study design

The Naranjo12 13 scale and the FDA algorithm14–16 were modified for use with dietary supplements. Two hundred case reports were randomly sampled from a database of adverse event reports associated with dietary supplements. Case reports in the database were based on consumers’ voluntary reports through telephone calls to the consumer information centre in Japan and were not standardised for the evaluation of causal relationships. We recruited assessors from six institutions in Japan (University of Shizuoka, Keio University, Kikugawa General Hospital, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital, Shizuoka City Public Health Center and Hamamatsu Institute of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics) by announcement. Nineteen assessors (4 dietary supplement experts, 4 pharmacists and 11 registered dietitians; 5 men and 14 women) enrolled and evaluated the case reports by alternately using the modified Naranjo scale and the modified FDA algorithm. The characteristics of the 19 assessors are shown in table 1. Three dietary supplement experts worked at a general hospital and one worked at a university as a full professor. All four of the pharmacists worked at a general hospital. Four of the registered dietitians worked at a general hospital, and seven worked at a city healthcare centre. None of the assessors received any training in the use of the two scales, and they were not familiar with causal assessment of adverse drug reactions since earlier.

Table 1.

Assessor characteristics

| Dietary supplement expert | Pharmacist | Registered dietitian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n | 4 | 4 | 11 |

| Age, mean±SD | 65.8±11.5 | 37.8±7.8 | 42.2±12.4 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 1 (9) |

| Women | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 10 (91) |

| Career length, mean years±SD | 33.5±2.4 | 8.6±13.8 | 13.9±17.4 |

Assessment scale design

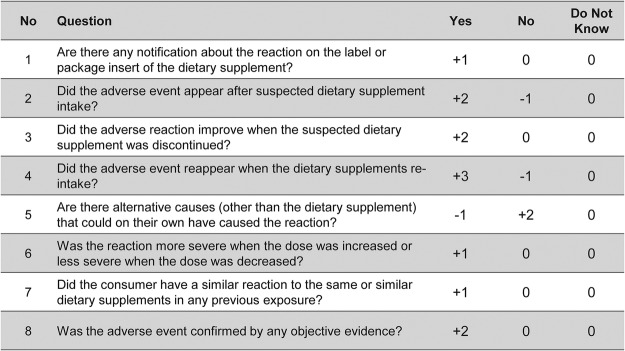

Modified Naranjo scale

The modified Naranjo scale is shown in figure 1. The phrase ‘drug’ in the Naranjo scale was changed to ‘dietary supplement’. The section in question 3 of the Naranjo scale pertaining to a specific antagonist was deleted. Questions regarding placebo and blood (or other fluid) concentrations were excluded. In addition to these changes, the scoring for questions pertaining to readministration and confirmation by objective evidence was changed by adding one point for positive answers to the original version of the Naranjo scale. The adverse event reports were assigned to a probability category using the total scores as follows: ≥9 highly probable, 5–8 probable, 3–4 highly possible, 1–2 possible, ≤0 unlikely. Case reports lacking information about time relationships were excluded and categorised as ‘lack of information’.

Figure 1.

Modified Naranjo scale.

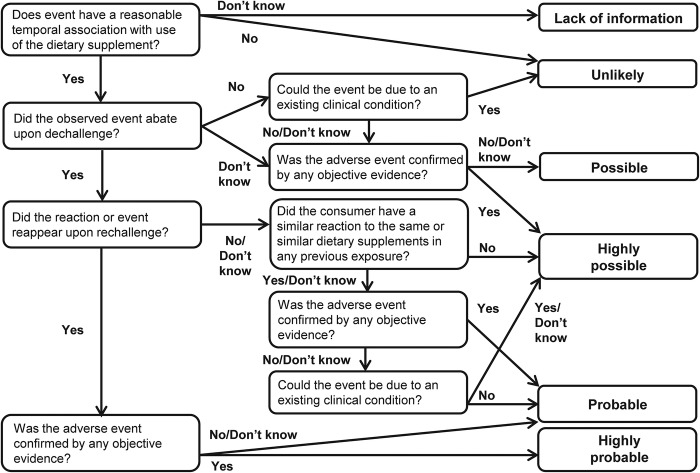

Modified FDA algorithm

Details of the FDA algorithm have been described previously.16 The modified FDA algorithm is shown in figure 2. There was limited information included in the dietary supplement case reports, so the number of options for questions was changed from 2 to 3: ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Don't know’. The scale was structured with 4 primary questions and 5 branch questions. The contents of the main questions were as follows: (1) the temporal relationship; (2) changes in symptoms due to the dietary supplement being discontinued; (3) rechallenges and (4) objective evidence from laboratory tests such as a drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test or patch test. Each of these questions had branch questions relating to: (1) existing clinical conditions; (2) objective evidence from laboratory tests such as a drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test or patch test and (3) previous experiences of adverse events after taking the same or similar (eg, including the same ingredient) dietary supplement. Adverse event reports were assigned to one of the following probability categories on the basis of the answers to these questions: lack of information, unlikely, possible, highly possible, probable and highly probable.

Figure 2.

Modified Food and Drug Administration (FDA) algorithm.

Statistical analysis

In order to quantify the level of agreement in the modified Naranjo scale, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) with a 95% CI were calculated using the methods described by Shrout and Fleiss.20 ICCs were interpreted according to the following criteria:<0.40, poor agreement; 0.40–0.75, moderate agreement and >0.75, excellent agreement.21

Inter-rater (multirater) reliability for the modified Naranjo scale and the modified FDA algorithm was analysed using Fleiss’ κ with a SE.22 Fleiss’ κ values were also calculated for each question of the modified Naranjo scale. The 95% CI of Fleiss’ κ was calculated from its SE. Fleiss’ κ values were interpreted according to the criteria defined by Landis and Koch23: −1.00, total disagreement; 0.00, no agreement; 0.01–0.20, slight agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement; 0.81–0.99 almost perfect agreement and 1.00, perfect agreement. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

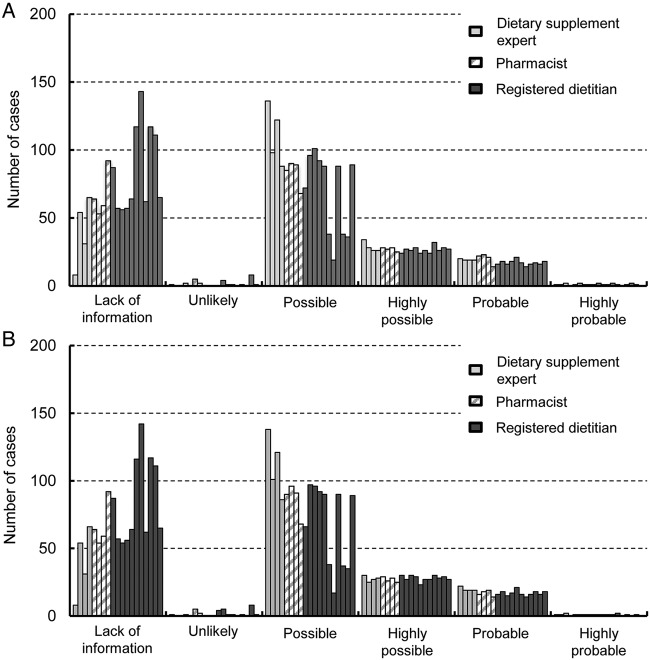

The modified Naranjo scale and the modified FDA algorithm are shown in figures 1 and 2. All assessors evaluated 200 case reports using the modified Naranjo scale and the modified FDA algorithm. No results were missing from the case report evaluations. The distribution of evaluation results is shown in figure 3A, B. These case reports were based on voluntary consumer reports, included incomplete reporting and were not standardised for the evaluation of causal relationships. Most of the 200 case reports were categorised as ‘lack of information’ or ‘possible’. The median (range) of cases in ‘lack of information’ using the modified Naranjo scale was 64 (8-143) and the corresponding values using the modified FDA scale were 64 (8-142) cases. The ‘possible’ category included a median (range) of 88 (19-136) cases using the modified Naranjo scale and 90 (17-138) cases using the modified FDA scale. The information on dosage, previous similar events and objective evidence was particularly poorly reported in these case reports. A large proportion of the cases were mild. Skin symptoms such as pruritus (n=56) and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal discomfort (n=62) were the most common. However, two serious adverse events related to hepatic dysfunction were reported. In one serious case, a woman started to take a dietary supplement for weight loss. Two weeks after commencing this treatment, her health deteriorated and she presented at a general hospital. Laboratory analyses revealed abnormal hepatic enzyme results and she was diagnosed with liver dysfunction. This condition resolved after over 2 weeks of hospitalisation. The attending doctor considered that the patient's dietary supplement had caused her liver dysfunction. In another case, a woman had been taking a dietary supplement for weight control for several months and had experienced fatigue for several weeks. She presented at a general hospital, where laboratory analyses revealed abnormal hepatic enzyme results and she was diagnosed with hepatitis. Her attending doctor considered that this was due to the dietary supplement. The patient's hepatitis improved after around 2 weeks’ hospitalisation.

Figure 3.

(A) Distribution of results for the modified Naranjo scale. (B) Distribution of results for the modified Food and Drug Administration (FDA) algorithm.

Modified Naranjo scale

The ICCs and Fleiss’ κ coefficient (Fleiss’ κ) values for the modified Naranjo scale are shown in table 2. The ICCs (95% CI) for each assessor group were as follows: dietary supplement experts, 0.865 (0.836 to 0.891); pharmacists, 0.890 (0.865 to 0.911) and registered dietitians, 0.882 (0.859 to 0.903). For the entire group of assessors, this value was 0.873 (0.850 to 0.895). Fleiss’ κ values (95% CI) for each assessor group were as follows: dietary supplement experts, 0.598 (0.596 to 0.599); pharmacists, 0.791 (0.790 to 0.792) and registered dietitians, 0.610 (0.609 to 0.610). For the entire group of assessors, this value was 0.615 (0.615 to 0.615). The levels of agreement based on the ICCs for each assessor group and all assessors combined were excellent. Inter-rater (multirater) reliability classifications based on Fleiss’ κ were as follows: fair agreement among dietary supplement experts and substantial agreement among pharmacists, registered dietitians and the entire group as a whole.

Table 2.

ICC and Fleiss’ κ coefficient values for the modified Naranjo scale and the modified FDA algorithm

| Modified Naranjo scale |

Modified FDA algorithm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| κ Coefficient (95% CI) | ICC (95% CI) | κ Coefficient (95% CI) | |

| Dietary supplement expert (n=4) | 0.598 (0.596 to 0.599) | 0.865 (0.836 to 0.891) | 0.596 (0.594 to 0.598) |

| Pharmacist (n=4) | 0.791 (0.790 to 0.792) | 0.890 (0.865 to 0.911) | 0.780 (0.779 to 0.781) |

| Registered dietitian (n=11) | 0.610 (0.609 to 0.610) | 0.882 (0.859 to 0.903) | 0.624 (0.623 to 0.624) |

| Total (n=19) | 0.615 (0.615 to 0.615) | 0.873 (0.850 to 0.895) | 0.622 (0.622 to 0.622) |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

Fleiss’ κ values (95% CI) for each question of the modified Naranjo scale were as follows: item 1 (product labelling), 0.048 (−0.169 to 0.264); item 2 (temporal relationship), 0.530 (0.530 to 0.531); item 3 (changes in adverse event after discontinuation), 0.944 (0.943 to 0.945); item 4 (rechallenges), 0.861 (0.857 to 0.866); item 5 (other factors related to the adverse event), 0.585 (0.584 to 0.585); item 6 (dose dependency), 0.797 (0.754 to 0.840); item 7 (adverse event history), 0.057 (0.022 to 0.093) and item 8 (objective evidence from laboratory tests), 0.561 (0.519 to 0.603). Items 1 and 7 showed the two lowest levels of agreement.

Modified FDA algorithm

Fleiss’ κ values for the modified FDA algorithm are shown in table 2. Fleiss’ κ values (95% CI) for each assessor group were as follows: dietary supplement experts, 0.596 (0.594 to 0.598); pharmacists, 0.780 (0.779 to 0.781) and registered dietitians, 0.624 (0.623 to 0.624). For all 19 assessors, this value was 0.622 (0.622 to 0.622). Inter-rater (multirater) reliability based on Fleiss’ κ values were as follows: fair agreement among dietary supplement experts; substantial agreement among pharmacists, registered dietitians and the entire group of assessors as a whole.

Discussion

In this study, we modified the Naranjo scale and the FDA algorithm and used them to evaluate case reports of adverse reactions to dietary supplements. These reports were assessed by dietary supplement experts, pharmacists and registered dietitians.

Agreement levels for the Naranjo scale, based on ICCs for each individual group and the assessor group as a whole, were classified as ‘excellent’. Fleiss’ κ values for each assessor group and for the group as a whole also demonstrated more than fair agreement. These results indicated that the modified Naranjo scale would be useful for evaluating the causal relationships between adverse events and dietary supplements. It may also have broad utility among different professions. The only concerns were items 1 and 7 (product labelling and adverse event history, respectively), which produced the two lowest levels of agreement. To remedy this, assessors might easily obtain the information from consumers as they are reporting the adverse events. Revising these two items and also recording consumers’ reports as they occur may improve the inter-rater (multirater) reliability and usability of the modified Naranjo scale.

The modified FDA algorithm showed more than fair agreement between each assessor group and within the entire group. Like the Naranjo scale, it has broad utility and would be useful for assessing the causality of adverse events.

For both methods, the inter-rater (multirater) reliability ratings determined using ICCs and Fleiss’ κ analyses showed more than substantial agreement in the entire group of assessors. In fact, the Fleiss’ κ values were very similar (0.615 for the modified Naranjo scale vs 0.622 for the modified FDA algorithm). Between them, scientists could select the one that best suits their purpose.

A large proportion of the 200 cases assessed in this study reported mild symptoms, although two serious cases with hepatic dysfunction were included. Although mild symptoms are not life-threatening, they do affect the quality of life. Therefore, analysis of causal relationships and the provision of information can improve the safety of dietary supplement usage. The number of serious adverse events was limited but these can lead to severe disability; the analysis of causality using this method can lead to prompt diagnosis and treatment, as well as regulatory actions.

There were several limitations to this study. The main limitation was the distribution of evaluation results. For both evaluation methods, most of the 200 case reports were categorised as ‘lack of information’ or ‘possible’. This may reflect the limited information included in the case reports used in this study. Case reports were based on voluntary consumer telephone calls and were not structured to facilitate evaluation of causal relationships. This might have affected the inter-rater (multirater) reliability ratings. In fact, most of the disagreements among assessors related to classification as either ‘lack of information’ or ‘possible’, while there was fairly good agreement concerning ‘highly possible’, ‘probable’ and ‘highly probable’ cases. This may be due to the evaluation based on speculation of each assessor in the cases categorised as ‘lack of information’ or ‘possible’. Structured or semistructured standardised interviews of consumers can improve the quality of information in case reports. When designing a structured or semistructured interview form, information on dosage, previous similar events and objective evidence should be requested, in addition to the essential information regarding temporal association and discontinuation. Even in the cases categorised as ‘probable’, some of these items of information were absent. For example, a man started to take a dietary supplement for health enhancement, and then developed oral inflammation. After discontinuation of the supplement, his oral inflammation resolved. When he started to take the dietary supplement again, oral inflammation recurred and he then stopped taking the supplement. This case included information on temporal association, discontinuation and rechallenge, but lacked information on dosage, previous similar events and objective evidence. Validity of the methods may also be a limitation. We estimated inter-rater (multirater) reliability using ICCs and Fleiss’ κ. However, these methods were not validated. Future studies could validate these methods in different populations in order to address this limitation and expand the potential for application of our methods in other clinical and regulatory settings. For example, medical institutions and regulatory agencies might use these modified methods to screen for adverse effects associated with dietary supplements, which may accelerate the detection of harmful events.

The FDA currently operates the Safety Reporting Portal24 for organisations, professionals and consumers. The Safety Reporting Portal is the electronic version of MedWatch 3500, 3500A and 3500B,25 which are voluntary reporting forms for adverse events, tailored to dietary supplements. However, researchers point out that these data sets contain many incomplete reports. Other national or local health departments are often the first to detect harm,9 because these forms are detailed and possibly too complicated for people to use.26 Combining a screening tool with detailed surveillance will make the reporting system more user friendly. This may promote voluntary reporting and lead to more rapid detection of harmful events.

In summary, we present a modified Naranjo scale and a modified FDA algorithm that may be used to assess the causal relationships between adverse events and dietary supplements. These tools might also be used by regulatory agencies to screen for adverse supplement events, but additional studies are needed to expand the possibilities for application of our methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assessors in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: KI, HY and M Kitagawa designed the study. KI, HY, YB, M Kitagawa, KM, M Kaji and KU performed the research and collected the data. YK, KI and YB analysed the data. KI, HY and YK wrote the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the contents of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (No. 24220501 to HY and KU), and a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (No.15J10190 to KI).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Shizuoka (No. 26-6, 2014).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.5ts48.

References

- 1.Vergari F, Tibuzzi A, Basile G. An overview of the functional food market: from marketing issues and commercial players to future demand from life in space. Adv Exp Med Biol 2010;698:308–21. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7347-4_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Cazarin ML, Wambogo EA, Regan KS et al. Dietary supplement research portfolio at the NIH, 2009–2011. J Nutr 2014;144:414–18. 10.3945/jn.113.189803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imai T, Nakamura M, Ando F et al. Dietary supplement use by community-living population in Japan: Data from the National Institute for Longevity Sciences Longitudinal Study of Aging (NILS-LSA). J Epidemiol 2006;16:249–60. 10.2188/jea.16.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stickel F, Shouval D. Hepatotoxicity of herbal and dietary supplements: an update. Arch Toxicol 2015;89:851–65. 10.1007/s00204-015-1471-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel DN, Low WL, Tan LL et al. Adverse events associated with the use of complementary medicine and health supplements: An analysis of reports in the Singapore Pharmacovigilance database from 1998 to 2009. Clin Toxicol 2012;50:481–9. 10.3109/15563650.2012.700402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haller C, Kearney T, Bent S et al. Dietary supplement adverse events: report of a one-year poison center surveillance project. J Med Toxicol 2008;4:84–92. 10.1007/BF03160960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV et al. Dietary supplements in a national survey: prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:1966–74. 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittler MH, Schmidt K, Ernst E. Adverse events of herbal food supplements for body weight reduction: systematic review. Obes Rev 2005;6:93–111. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen PA. Hazards of hindsight—monitoring the safety of nutritional supplements. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1277–80. 10.1056/NEJMp1315559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankos VH, Street DA, O'Neill RK. FDA regulation of dietary supplements and requirements regarding adverse event reporting. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;87:239–44. 10.1038/clpt.2009.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiba T, Sato Y, Nakanishi T et al. Inappropriate usage of dietary supplements in patients by miscommunication with physicians in Japan. Nutrients 2014;6:5392–404. 10.3390/nu6125392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busto U, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Comparison of two recently published algorithms for assessing the probability of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1982;13:223–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01361.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irey NS. Adverse drug reactions and death. A review of 827 cases. JAMA 1976;236:575–8. 10.1001/jama.1976.03270060025021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karch FE, Lasagna L. Toward the operational identification of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1977;21:247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones JK. Adverse drug reactions in the community health setting: approaches to recognizing, counseling, and reporting. Fam Community Health 1982;5:58–67. 10.1097/00003727-198208000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer MS, Leventhal JM, Hutchinson TA et al. An algorithm for the operational assessment of adverse drug reactions. I. Background, description, and instructions for use. JAMA 1979;242:623–32. 10.1001/jama.1979.03300070019017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallagher RM, Kirkham JJ, Mason JR et al. Development and inter-rater reliability of the Liverpool adverse drug reaction causality assessment tool. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e28096 10.1371/journal.pone.0028096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on safety monitoring of herbal medicines in pharmacovigilance systems. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s7148e/s7148e.pdf (accessed 5 Jun 2015).

- 20.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosner B. Fundamentals of biostatistics. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull 1971;76:378 10.1037/h0031619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safety Reporting Portal. https://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov/ (accessed 5 Jun 2015).

- 25.Kessler DA. Introducing MEDWatch. A new approach to reporting medication and device adverse effects and product problems. JAMA 1993;269:2765–8. 10.1001/jama.1993.03500210065033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Getz KA, Stergiopoulos S, Kaitin KI. Evaluating the completeness and accuracy of MedWatch data. Am J Ther 2014;21:442–6. 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318262316f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]