Abstract

Objective

To assess the 1 year clinical outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism using a 500 kHz femtosecond laser system.

Methods

This prospective study evaluated 52 eyes of 39 consecutive patients (31.8±6.9 years, mean age±SD) with spherical equivalents of −4.11±1.73 D (range, −1.25 to −8.25 D) who underwent SMILE for myopia and myopic astigmatism. Preoperatively, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively, we assessed the safety, efficacy, predictability, stability, corneal endothelial cell loss and the adverse events of the surgery.

Results

The logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) uncorrected distance visual acuity and LogMAR corrected distance visual acuity were −0.16±0.11 and −0.22±0.07, respectively, 1 year postoperatively. At 1 year, all eyes were within±0.5 D of the targeted correction. Manifest refraction changes of −0.05±0.32 D occurred from 1 week to 1 year postoperatively (p=0.20, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The endothelial cell density was not significantly changed from 2804±267 cells/mm2 preoperatively to 2743±308 cells/mm2 1 year postoperatively (p=0.12). No vision-threatening complications occurred during the observation period.

Conclusions

SMILE performed well in the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism, and no significant change in endothelial cell density or any other serious complications occurred throughout the 1-year follow-up period, suggesting its viability as a surgical option for the treatment of such eyes.

Keywords: OPHTHALMOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Early visual and refractive outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) are encouraging, but most of these postoperative follow-ups are spanning 3–6 months. Moreover, the endothelial cell loss after this surgical procedure, which is a major concern in the prognosis of the patient, has not so far been fully elucidated.

Although we did not assess corneal biomechanics and ocular surface parameters in this study, this is long-term study did assess the safety, efficacy, predictability, stability and adverse events of SMILE.

SMILE was beneficial in terms of safety, efficacy, predictability and stability for the correction of myopic refractive errors, and neither significant endothelial cell loss nor vision-threatening complications occurred throughout the 1 year follow-up period.

Introduction

The femtosecond laser allows very precise cuts with less thermal damage to the tissues than seen with other lasers, and it is therefore one of the most revolutionary technologies to be seen in medical care in recent years. In ophthalmology, it has been utilised mainly for making corneal flaps for laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) with high precision, instead of using a microkeratome. This technology has enabled us to develop a novel surgical technique called refractive lenticule extraction (ReLEx), which does not require a microkeratome or an excimer laser, but requires only the femtosecond laser system. Laser-induced extraction of a refractive lenticule was first applied in highly myopic eyes1 and in blind or amblyopic eyes.2 Additionally, the ReLEx technique can be utilised not only for femtosecond lenticule extraction (FLEx)3–6 by lifting the flap, but also for small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE)4 6–21 without lifting the flap, and has been proposed as a new surgical approach for the correction of myopic refractive errors.

Early clinical outcomes of SMILE are encouraging, but most of these postoperative follow-ups span 3–6 months,6–14 16–19 except in a few studies.15 20 21 In consideration of the prevalence of this novel technique, more studies of long duration using different groups are necessary for confirmation of these preliminary findings. The purpose of this study is to prospectively assess the 1 year clinical outcomes, including endothelial cell loss, of SMILE for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism.

Materials and methods

Study population

This prospective study comprised 52 eyes of 39 patients (10 men and 29 women) who underwent SMILE for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism, using the VisuMax femtosecond laser system (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) with a 500 kHz repetition rate, at the Kitasato University Hospital. The patients were recruited in a continuous cohort. The mean patient age at the time of surgery was 31.8±6.9 years (range, 20–49 years). The sample size in this study offered 94% statistical power at the 5% level in order to detect a 0.10 difference in logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) of visual acuity, when the SD of the mean difference was 0.20, and offered 81% statistical power at the 5% level in order to detect a 80 cells/mm2 difference in the endothelial cell density before and after surgery, when the SD of the mean difference was 200 cells/mm2. The inclusion criteria for this surgical technique in our institution were as follows: dissatisfaction with spectacle or contact lens correction, manifest spherical equivalent of −1.25 to −9 diopters (D), manifest cylinder of 0–4 D, sufficient corneal thickness (estimated total postoperative corneal thickness >400 μm and estimated residual thickness of the stromal bed >250 μm), endothelial cell density ≥1800 cells/mm2, no history of ocular surgery, severe dry eye, progressive corneal degeneration, cataract or uveitis. Eyes with keratoconus were excluded from the study by using a Placido disk videokeratography (TMS-2, Tomey, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan) keratoconus screening test. We aimed to fully correct the preoperative manifest refraction in all eyes. Routine postoperative examinations were performed at 1 day, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery. Preoperatively, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively, we determined the following: logMAR of uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA), logMAR of corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), manifest spherical equivalent refraction and endothelial cell density (preoperatively and 1 year postoperatively), in addition to the usual slit-lamp biomicroscopic and funduscopic examinations. Before surgery, the mean keratometric readings and the central corneal thickness were measured using an autorefractometer (ARK-700A, Nidek, Gamagori, Japan) and an ultrasound pachymeter (DGH-500, DGH Technologies, Exton, Pennsylvania, USA), respectively. The endothelial cell density was determined with a non-contact specular microscope (SP-8800, Konan Medical, Nishinomiya, Japan). The manufacturer’s software automatically produced an endothelial cell density measurement by visually comparing the cell size in the image with the predefined patterns on the screen. Each measurement was repeated at least three times, and the average value was used for analysis. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study.

Surgical procedure

SMILE was performed using the VisuMax femtosecond laser system with a 500 kHz repetition rate as described previously.6 The laser was visually centred on the pupil. A small (S) curved interface cone was used in all eyes. In order, the femtosecond incisions were performed as follows: the posterior surface of the lenticule (spiral in pattern), the anterior surface of the lenticule (spiral out pattern), followed by a side cut of cap. The femtosecond laser parameters were as follows: 120 μm cap thickness, 7.5 mm cap diameter, 6.5 mm lenticule diameter, 140 nJ power for lenticule making a 3 mm side cut for access to the lenticule, with angles of 90°. A spatula was inserted through the side cut over the top of the lenticule dissecting this plane, followed by the bottom of the lenticule. The lenticule was subsequently grasped with modified McPherson forceps (Geuder, GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), and removed. The intrastromal space was flushed with balanced salt solution using a cannula. No adjustments to the manufacturer's nomograms were made. Postoperatively, steroidal (0.1% betamethasone, Rinderon, Shionogi, Osaka, Japan) and antibiotic (0.3% levofloxacin, Cravit, Santen, Osaka, Japan) medications were topically administered four times per day for 2 weeks, with the dose being reduced gradually thereafter.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using commercially available statistical software (Ekuseru-Toukei 2010, Social Survey Research Information Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The normality of all data samples was first checked by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since the data did not fulfil the criteria for normal distribution, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for statistical analysis to compare the presurgical and postsurgical data. The relationship between two sets of data was analysed by Spearman’s rank correlation test. Unless otherwise indicated, the results are expressed as mean±SD, and a value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient population

Preoperative patient demographics of the study population are summarised in table 1. No eyes were lost during the 1 year follow-up in this study population.

Table 1.

Preoperative demographics of the study population

| Demographic data | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.8±6.9 (range 20–49) |

| Gender (% female) | 74 |

| LogMAR UDVA | 1.12±0.11 (range 0.52–1.52) |

| LogMAR CDVA | −0.22±0.08 (range, −0.30 to −0.18) |

| Manifest spherical equivalent (D) | −4.11±1.73 D (range −1.25 to −8.25 D) |

| Manifest cylinder (D) | −0.51±0.65 D (range 0.00 to −2.25 D) |

| Mean keratometric reading (D) | 43.3±1.33 D (range 40.4–46.0 D) |

| Central corneal thickness (μm) | 546.1±32.9 μm (range 471–614 μm) |

| Endothelial cell density (cells/mm2) | 2804±267 cells/mm2 (range 2275–3362 cells/mm2) |

CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; D, dioptre; LogMAR, logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; UDVA, uncorrected distance visual acuity.

Safety

LogMAR CDVA was −0.15±0.07, −0.19±0.07, −0.20±0.08, −0.20±0.07 and −0.22±0.07, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, respectively. We found no significant difference between preoperative CDVA and 1 year postoperative CDVA (p=0.48, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The safety index was 0.86±0.17, 0.95±0.24, 0.97±0.21, 0.97±0.21 and 1.00±0.20, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively, respectively. Thirty-three eyes (63.5%) showed no change in CDVA, eight eyes (15.4%) gained one line, while nine eyes (17.3%) lost one line and two eyes (3.8%) lost two lines 1 year postoperatively (figure 1). Although two eyes lost two lines, possibly because of a very mild interface haze formation and/or irregular astigmatism, these eyes had a CDVA of 20/20 or better.

Figure 1.

Changes in corrected distance visual acuity 3 months and 1 year after small incision lenticule extraction (postop, postoperative).

Effectiveness

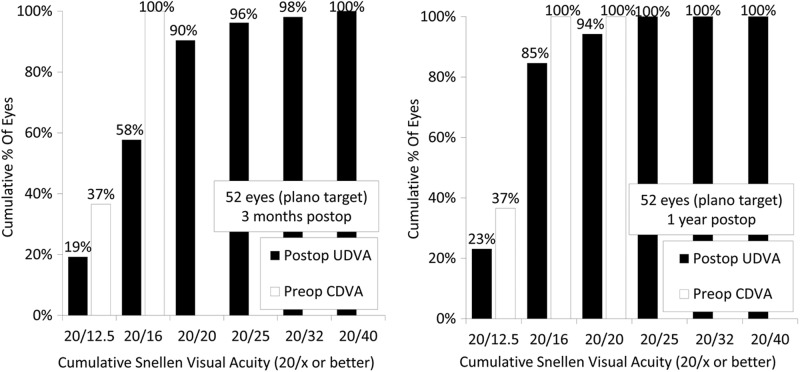

LogMAR UDVA was −0.08±0.13, −0.12±0.11, −0.13±0.13, −0.14±0.12 and −0.16±0.11, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, respectively. We found a significant difference between preoperative UDVA and 1 year postoperative UDVA (p<0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The efficacy index was 0.75±0.21, 0.83±0.24, 0.84±0.25, 0.86±0.25 and 0.91±0.25, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively, respectively. The cumulative percentages of eyes attaining specified cumulative levels of UDVA 1 year postoperatively are shown in figure 2. One week and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, 100%, 100%, 100%, 100% and 100% of eyes, and 81%, 85%, 90%, 92% and 94% of eyes had a UDVA of 20/40, and of 20/20 or better, respectively.

Figure 2.

Cumulative percentages of eyes attaining specified cumulative levels of UDVA 3 months and 1 year after SMILE (CDVA, corrected distance visual acuity; SMILE, small incision lenticule extraction; UDVA, uncorrected distance visual acuity) (postop, postoperative; preop, preoperative).

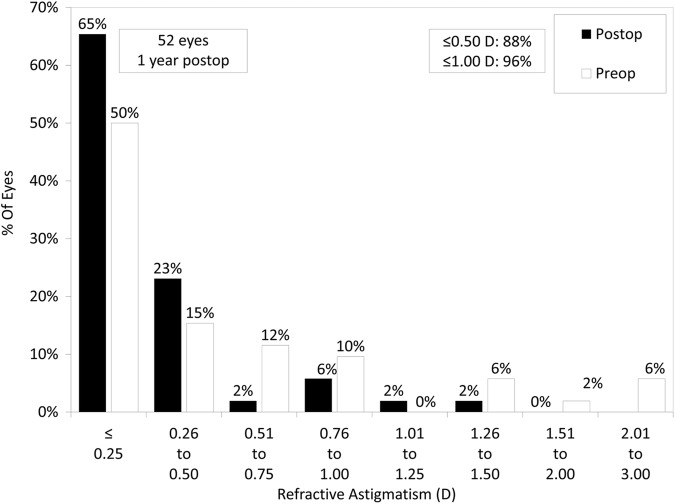

Predictability

A scatter plot of the attempted versus the achieved manifest spherical equivalent correction at 1 year postoperatively is shown in figure 3. The percentages of eyes within different dioptre ranges of the attempted correction and refractive astigmatism are shown in figures 4 and 5, respectively. One week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, 94%, 98%, 96%, 96% and 100% of eyes, and 98%, 100%, 100%, 100% and 100% of eyes were within±0.5, and ±1.0 D of the attempted spherical equivalent correction, respectively.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of the attempted versus the achieved manifest spherical equivalent correction 1 year after small incision lenticule extraction (postop, postoperative).

Figure 4.

Percentages of eyes within different dioptre ranges of the attempted correction (spherical equivalent) 3 months and 1 year after small incision lenticule extraction (postop, postoperative).

Figure 5.

Percentages of eyes within different dioptre ranges of refractive astigmatism before and 1 year after small incision lenticule extraction (postop, postoperative).

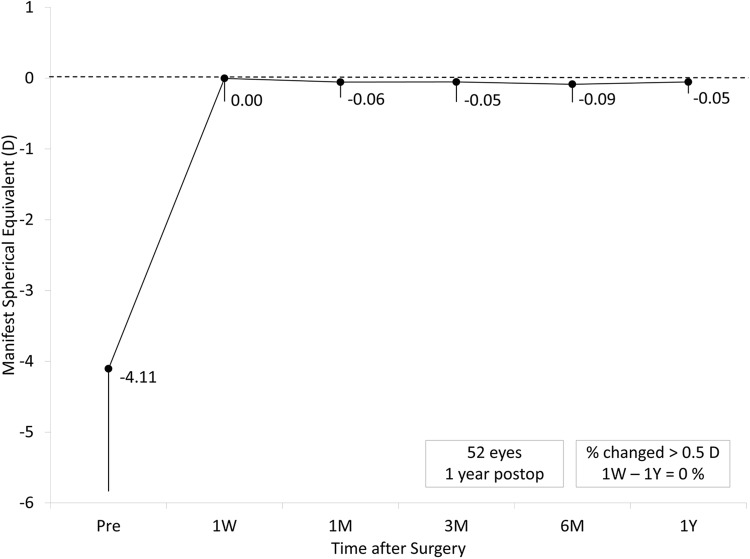

Stability

The change in the manifest spherical equivalent is shown in figure 6. One week, and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, the mean manifest spherical equivalent was 0.00±0.32, −0.06±0.21, −0.05±0.28, −0.09±0.25 and −0.05±0.16 D, respectively. Manifest spherical equivalent was decreased, but not significantly, from 0.00±0.35 D 1 week postoperatively, to −0.05±0.16 D 1 year postoperatively (p=0.201, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Figure 6.

Time course of manifest spherical equivalent after small incision lenticule extraction (postop, postoperative).

Endothelial cell density

The endothelial cell density was decreased, but not significantly, from 2804±267 cells/mm2 preoperatively to 2743±308 cells/mm2 1 year postoperatively (p=0.12, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The preoperative and postoperative endothelial cell density and the lenticule thickness according to the degree of myopia are shown in table 2. The mean percentage of endothelial cell loss was 2.0% 1 year after surgery. We found no significant correlation of the endothelial cell loss, with the amount of spherical equivalent correction (Spearman correlation coefficient r=0.14, p=0.34), or with the lenticule thickness (r=0.12, p=0.38).

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative endothelial cell density and lenticule thickness according to the degree of myopia in eyes undergoing SMILE

| Low myopia | Moderate myopia | High Myopia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (≥−3 D) | (−3 D>, ≥−6 D) | (<−6 D) | |

| Number of eyes (%) | 14 (27%) | 32 (62%) | 6 (12%) |

| Lenticule thickness (µm) | 48.6±10.2 | 91.0±13.1 | 128.3±8.6 |

| Preoperative ECD (cells/mm2) | 2859±191 | 2804±300 | 2676±215 |

| Postoperative ECD (1 year)(cells/mm2) | 2834±229 | 2736±332 | 2564±289 |

| Endothelial cell loss (%) | 0.8±5.9 | 2.1±10.1 | 4.3±6.1 |

ECD, endothelial cell density; SMILE, small incision lenticule extraction.

Secondary surgeries/adverse events

A suction loss occurred in one eye (2%), but we successfully completed the procedure after the contact glass was immediately reattached. This eye had UDVA and CDVA of 20/16 1 year postoperatively. Otherwise, no significant intraoperative complication was found. Transient interface haze and optically insignificant peripheral microstriae developed in six eyes (12%) and two eyes (4%), respectively, during the first postoperative month. All these eyes were followed without additional surgical intervention, and gradually resolved thereafter. No epithelial ingrowth, diffuse lamellar keratitis, keratectasia, or other vision-threatening complications were seen at any time during the 1 year observation period.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that SMILE was beneficial in terms of safety, efficacy, predictability and stability, for the correction of myopic refractive errors, throughout the 1 year observation period. Previous studies on the visual and refractive outcomes of SMILE are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Previous studies on visual and refractive outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE)

| Author | Year | Repetition rate | Eyes | Follow-up | Age | Spherical equivalent | Astigmatism | Safety | Efficacy | Predictability |

Stability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kHz) | (months) | (years) | (D) | (D) | (logMAR CDVA) | (logMAR UDVA) | Within±0.5 D (%) | within±1.0 D (%) | (D) | |||

| Shah et al7 | 2011 | 200 | 51 | 6 | 26.0±5.55 | −4.87±2.16 | −0.76±0.98 | 70% unchanged | 79% ≤0.16 logMAR | 91 | 100 | −0.06 |

| 25% gained 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| 6% lost 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| Sekundo et al8 | 2011 | 200 | 91 | 6 | 35.6 | −4.75±1.56 | −0.78±0.79 | 49% unchanged | 83.5% ≤0.00 logMAR | 80.2 | 95.6 | 0.05 |

| 35.6% gained 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| 11% lost 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| Vestergaard et al10 | 2012 | 500 | 279 | 3 | 38.1±8.7 | −7.18±1.57 | −0.71±0.50 | −0.03±0.07 | 95% ≤0.30 logMAR | 77 | 95 | −0.18 |

| Hjortdal et al11 | 2012 | 500 | 670 | 3 | 38.3±8.3 | −7.19±1.30 | −0.60±0.46 | −0.049±0.097 | 84% ≤0.16 logMAR | 80.1 | 94.2 | −0.25±0.44 (undercorrection) |

| Kamiya et al6 | 2014 | 500 | 26 | 6 | 31.5±6.2 | −4.21±2.63 | −0.54±0.74 | −0.19±0.07 | −0.15±0.20 | 100 | 100 | 0.00±0.30 |

| Sekundo et al15 | 2014 | 500 | 53 | 12 | 29 | −4.68±1.29 | −0.41±0.51 | 47% unchanged | 88% ≤0.00 logMAR | 92 | 100 | −0.08 |

| 42% gained 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| 11% lost 1 line | ||||||||||||

| Vestergaard et al16 | 2014 | 500 | 34 | 6 | 35±7 | −7.56±1.11 | – | −0.08±0.08 | −0.04±0.06 | 88 | 97 | −0.17±0.34 |

| Ivarsen et al17 | 2014 | 500 | 1574 | 3 | 38±8 | −7.25±1.84 | −0.93±0.90 | −0.05±0.10 | – | – | – | −0.15±0.50 |

| Lin et al18 | 2014 | – | 60 | 3 | 25.9±6.4 | −5.13±1.75 | −0.57±0.47 | 96.7% unchanged | 85% ≤0.00 logMAR | – | 98.3 | −0.09±0.38 |

| 3.3% lost 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| Ganesh and Gupta19 | 2014 | – | 50 | 3 | 27.4±5.6 | −4.95±2.09 | −0.53±0.93 | 88% unchanged | 84% ≤0.00 logMAR | – | – | −0.14±0.28 |

| 12% gained 1 line | ||||||||||||

| Reinstein et al20 | 2014 | 500 | 110 | 12 | 32.4±5.7 | −2.61±0.54 | −0.55±0.38 | 66% unchanged | 96% ≤0.00 logMAR | 84 | 99 | −0.05±0.36 |

| 25% gained 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| 9% lost 1 line | ||||||||||||

| Xu and Yang21 | 2015 | – | 52 | 12 | 24.5±6.0 | −5.53±1.70 | −0.64±0.51 | 67% unchanged | 83% ≤0.00 logMAR | 90.4 | 98.1 | −0.06±0.37 |

| 32% gained 1 line or more | ||||||||||||

| 1% lost 1 line | ||||||||||||

| Current | 500 | 52 | 12 | 31.8±6.9 | −4.11±1.73 | −0.51±0.65 | −0.22±0.07 | −0.16±0.11 | 100 | 100 | −0.05±0.32 | |

With regard to the safety and efficacy of the procedure, Shah et al7 demonstrated that 70%, 25% and 6% of eyes had an unchanged CDVA, gained one line or more and lost one line or more, respectively, and that 79% of eyes in which the targeted refraction was emmetropia had a UDVA of 20/25 or better. Sekundo et al8 reported that 53% of eyes remained unchanged, 32.3% gained one line, 3.3% gained two lines, 8.8% lost one line and 1.1% lost two lines of CDVA, and that 97.6% and 83.5% of eyes had a UCVA of 20/40 and 20/20 or better 6 months postoperatively. In a different study, they stated that the safety and efficacy indices were 1.08 and 0.99, respectively.15 Vestergaard et al10 reported that logMAR CDVA was −0.03±0.07, and that 95% of eyes had a UDVA of 10/20 or more 3 months postoperatively. Hjortdal et al11 also demonstrated that the safety and efficacy indices were 1.07±0.22 and 0.90±0.25 3 months postoperatively, respectively. In another study, we reported that logMAR CDVA and UDVA were −0.19±0.22 and −0.15±0.20 6 months postoperatively, respectively.6 Reinstein et al20 and Xu and Yang21 reported that 91% and 99% of eyes had an unchanged CDVA or had gained lines, and that 96% and 83% of eyes had a UDVA of 20/20 1 year postoperatively, respectively. Our current findings were comparable with the results of these previous studies in terms of safety, but the efficacy achieved in the current study was somewhat better than that of previous studies, presumably due to the slightly lower refractive correction and/or the use of the femtosecond laser with its higher repetition rate, in this study. We found a tendency for a slight delay in UDVA recovery in the early postoperative period after SMILE, which was in line with that after FLEx.5 6 Kunert et al22 showed that the surface regularity index decreased as pulse energy increased and that cases of interface haze were uncommon since they began applying lower energies. Further optimisation of the laser settings is necessary to improve visual outcomes not only after FLEx,5 6 but also after SMILE.

With regard to predictability, 77–100% and 94.2–100% of eyes have been reported to be within±0.5 and 1.0 D of the targeted correction, respectively.6–8 10 11 15–21

Hjortdal et al11 stated that the average difference between achieved correction and attempted correction was 0.25 D of undercorrection, which may be added when planning SMILE. The predictability achieved in this study was comparable to, or slightly higher than, that in other previous studies.6–8 10 11 15–21 The discrepancy may also be explained by the slightly lower refractive correction and the use of the femtosecond laser with its higher repetition rate, in the current study.

With regard to stability, Shah et al7 stated that the mean change in refraction from 1 month postoperatively was −0.02±0.18 and −0.06±0.27 D at 3 and 6 months postoperatively, respectively. Sekundo et al8 demonstrated that the mean refraction was 0.05, 0.14 and 0.10 D, 1 week, and 1 and 6 months after surgery, respectively. They also stated that the mean spherical equivalent gradually regressed by 0.08 D, from −0.11 D at 1 month postoperatively to −0.19 D at 1 year postoperatively.15 Vestergaard et al10 found a slight, but significant, regression from 1 week to 1 month, but no significant regression from 1 month to 3 months after SMILE. In another study, we demonstrated that changes of 0.00±0.30 D occurred in refraction from 1 week to 6 months after SMILE.6 Reinstein et al20 reported that the mean spherical equivalent was 0.10, −0.05 and −0.05 D, 1, 3 and 12 months postoperatively, respectively. Xu and Yang21 showed that the change in manifest refraction from 1 day to 1 year was −0.06±0.37 D. We found no significant refractive regression from 1 week to 1 year after SMILE in the current study. A careful long-term follow-up is still necessary for confirming whether refractive regression occurs in the late postoperative period.

After this surgical technique, we found no significant cell loss, which was comparable with the outcomes after excimer laser surgery such as LASIK and photorefractive keratectomy,23 24 or after FLEx.5 Ganesh and Brar25 recently reported that the endothelial cell density was changed, but not significantly, from 2695.13±222.8 cells/mm2 preoperatively to 2682.5±231.8 cells/mm2 1 year postoperatively, in eyes undergoing SMILE with accelerated cross-linking. Neither photodisruption for thinner cap making nor photodisruption for deeper lenticule manufacture induced a significant change in the endothelial cell density of the cornea, and the depth of photodisruption does not significantly affect the endothelial cell loss, both after FLEx7 and also after SMILE.

There are at least two limitations to this study. One is that we included both eyes of the same patient in the current study, although only one eye should be used for statistical analysis. We confirmed the similar outcomes of SMILE, even when only one eye was randomly chosen from each patient, and thus we enrolled both eyes of the same patient as described in many published studies on refractive surgery. Another limitation is that we did not evaluate corneal biomechanics or ocular surface parameters in all eyes. Since SMILE does not require flap making, it may have advantages over LASIK in terms of better biomechanical stability, better flap strength, reduced risk of flap dislocation, and milder dry eye symptoms. We are currently conducting a new study on corneal biomechanics and the ocular surface parameters after SMILE.

In conclusion, our results support the view that SMILE is beneficial for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism, and show that neither significant endothelial cell loss nor vision-threatening complications occurred throughout the 1 year follow-up period. This novel surgical approach appears to hold promise as an alternative to LASIK for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism.

Footnotes

Contributors: KK and KS were involved in the design and conduct of the study. KK, AI and HK were involved in collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data. KK, KS, AI and HK were involved in preparation, review and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kitasato University and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Krueger RR, Juhasz T, Gualano A et al. . The picosecond laser for nonmechanical laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg 1998;14:467–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratkay-Traub I, Ferincz IE, Juhasz T et al. . First clinical results with the femtosecond neodynium-glass laser in refractive surgery. J Refract Surg 2003;19:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekundo W, Kunert K, Russmann C et al. . First efficacy and safety study of femtosecond lenticule extraction for the correction of myopia: six-month results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:1513–20. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah R, Shah S. Effect of scanning patterns on the results of femtosecond laser lenticule extraction refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:1636–47. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamiya K, Igarashi A, Ishii R et al. . Early clinical outcomes, including efficacy and endothelial cell loss, of refractive lenticule extraction using a 500 kHz femtosecond laser to correct myopia. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38:1996–2002. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamiya K, Shimizu K, Igarashi A et al. . Visual and refractive outcomes of femtosecond lenticule extraction and small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:128–34. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah R, Shah S, Sengupta S. Results of small incision lenticule extraction: all-in-one femtosecond laser refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:127–37. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekundo W, Kunert KS, Blum M. Small incision corneal refractive surgery using the small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) procedure for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism: results of a 6 month prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:335–9. 10.1136/bjo.2009.174284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ang M, Tan D, Mehta JS. Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) versus laser in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK): study protocol for a randomized, non-inferiority trial. Trials 2012;13:75 10.1186/1745-6215-13-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vestergaard A, Ivarsen AR, Asp S et al. . Small-incision lenticule extraction for moderate to high myopia: predictability, safety, and patient satisfaction. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38:2003–10. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjortdal JØ, Vestergaard AH, Ivarsen A et al. . Predictors for the outcome of small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia. J Refract Surg 2012;28:865–71. 10.3928/1081597X-20121115-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riau AK, Ang HP, Lwin NC et al. . Comparison of four different VisuMax circle patterns for flap creation after small incision lenticule extraction. J Refract Surg 2013;29:236–44. 10.3928/1081597X-20130318-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozgurhan EB, Agca A, Bozkurt E et al. . Accuracy and precision of cap thickness in small incision lenticule extraction. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:923–6. 10.2147/OPTH.S45227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agca A, Ozgurhan EB, Demirok A et al. . Comparison of corneal hysteresis and corneal resistance factor after small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK: a prospective fellow eye study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2014;37:77–80. 10.1016/j.clae.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sekundo W, Gertnere J, Bertelmann T et al. . One-year refractive results, contrast sensitivity, high-order aberrations and complications after myopic small-incision lenticule extraction (ReLEx SMILE). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;252:837–43. 10.1007/s00417-014-2608-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vestergaard AH, Grauslund J, Ivarsen AR et al. . Efficacy, safety, predictability, contrast sensitivity, and aberrations after femtosecond laser lenticule extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014;40:403–11. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.07.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivarsen A, Asp S, Hjortdal J. Safety and complications of more than 1500 small-incision lenticule extraction procedures. Ophthalmology 2014;121:822–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin F, Xu Y, Yang Y. Comparison of the visual results after SMILE and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK for myopia. J Refract Surg 2014;30:248–54. 10.3928/1081597X-20140320-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesh S, Gupta R. Comparison of visual and refractive outcomes following femtosecond laser-assisted lasik with smile in patients with myopia or myopic astigmatism. J Refract Surg 2014;30:590–6. 10.3928/1081597X-20140814-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinstein DZ, Carp GI, Archer TJ et al. . Outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) in low myopia. J Refract Surg 2014;30:812–18. 10.3928/1081597X-20141113-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y, Yang Y. Small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia: results of a 12-month prospective study. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:123–31. 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunert KS, Blum M, Duncker GI et al. . Surface quality of human corneal lenticules after femtosecond laser surgery for myopia comparing different laser parameters. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:1417–24. 10.1007/s00417-010-1578-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SV, Bourne WM. Corneal endothelial cell loss 9 years after excimer laser keratorefractive surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:1423–7. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RT, Waring GO IV, Durrie DS et al. . Corneal endothelial cell density after femtosecond thin-flap LASIK and PRK for myopia: a contralateral eye study. J Refract Surg 2009;25:1098–102. 10.3928/1081597X-20091117-09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganesh S, Brar S. Clinical outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction with accelerated cross-linking (ReLEx SMILE Xtra) in patients with thin corneas and borderline topography. J Ophthalmol 2015;2015:263412 10.1155/2015/263412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]