Abstract

Objective

To compare reported birth weight (BW) information in school health records with BW from medical birth records, and to investigate if maternal and offspring characteristics were associated with any discrepancies.

Design

Register-based cohort study.

Setting

Denmark, 1973–1991.

Participants

The study was based on BW recorded in the Copenhagen School Health Records Register (CSHRR) and in The Medical Birth Register (MBR). The registers were linked via the Danish personal identification number.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Statistical comparisons of BW in the registers were performed using t tests, Pearson's correlation coefficients, Bland-Altman plots and κ coefficients. Odds of BW discrepancies >100 g were examined by logistic regressions.

Results

The study population included 47 534 children. From 1973 to 1979 when BW was grouped in 500 g intervals in the MBR, mean BW differed significantly between the registers. During 1979–1991 when BW was recorded in 10 and 1 g intervals, mean BW did not significantly differ between the two registers. BW from both registers was highly correlated (0.93–0.97). Odds of a BW discrepancy significantly increased with parity, the child's age at recall and by marital status (children of married women had the highest odds).

Conclusions

Overall, BW information in school health records agreed very well with BW from medical birth records, suggesting that reports of BWs in school health records in Copenhagen, Denmark generally are valid.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, OBSTETRICS, PAEDIATRICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large register-based study population.

Medical birth records are not always available but other sources of information might exist. Validation studies like the present one are useful in such circumstances.

Limited information on maternal and offspring characteristics was available.

Introduction

Birth weight (BW) has been identified as an important indicator of health for the child at birth, during infancy and also later in adult life.1–3 Officially recorded BW information is not always available to support current research into adult onset diseases, and it is therefore important to obtain valid information on BW collected retrospectively.

Owing to the identified associations between BW and later disease outcomes,4 information on BW is often included in epidemiological research. In many cases, BW information can be retrieved from birth or medical records; however, this is not always possible and the use of recalled information may be the only option.

In general, mothers recall the BW of their children with a high degree of accuracy;5–9 however, the accuracy varies between studies, possibly depending on the recall period (ranging from days to decades) and maternal characteristics. In one study, 58% of the mothers recalled their child's BW to within 100 g of the recorded BW 6 years after birth9 versus in two other studies where the rate was 92% at 9 months5 and 8–18 years after birth.6 As such, it is possible that parents recall their children's BWs very well, or that there is publication bias in this area as studies demonstrating low correlations or poor agreement were not identified in the literature.

Therefore, in this study, we compared reports of BW obtained at the first school examination and recorded in health records with the recorded BW from medical birth records, and we investigated if maternal and offspring characteristics predicted the discrepancies between BW values in the two registers.

Methods

Study population

The Copenhagen School Health Records Register (CSHRR) is a population-based register that includes virtually every schoolchild in Copenhagen born between 1930 and 1991 and includes 381 110 records. The register has been established in collaboration between the Institute of Preventive Medicine, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, The Capital Region and the Copenhagen City Archives. The computerised register contains basic information about each child (name, sex, date of birth, personal identification number), along with annual measures of height and weight throughout school ages. From the birth year of 1936 onwards, information on BW was obtained at the time of the school entry examination which typically occurred when the children were aged 5–7 years. During the years included in this study (1973–1991), BW was either obtained at the first school examination or via a returned health questionnaire. The source of the BW information contained in the school health records, however, was not noted. The CSHRR is described in greater detail elsewhere.10

The Medical Birth Register (MBR) is a national medical register that contains computerised information on all births in Denmark since 1973. Information on births was reported to the Danish Health Authorities on a form filled out by the midwife shortly after delivery. From 1973 to 1977, BW was recorded in 500 g units in the MBR; however, the rounding procedure was not documented. From 1978 to 1990, BW was recorded in 10 g units, and from 1991 onwards it was recorded in 1 g units. The MBR also contains information on gestational age which was measured in weeks from 1973 to 1978 and in days from 1978 onwards. The mother's age, parity and civil status were also registered in the MBR. Further details of the register can be obtained elsewhere.11

The Danish personal identification number was used to link the two registers during the overlapping period from 1973 to 1991, and children with BW information in the CSHRR and the MBR were identified.

An access and linkage permission was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2012-4-1156). This type of research based on pre-existing routinely collected data does not require ethical permission in Denmark.

We excluded children with BW values below 500 g, as these were likely to be erroneous on the basis of the chance of survival of very small children during the study period (O Pryds, personal communication 2014). On the basis of the highest BW reported in Denmark of 6 150 g, values above this level were excluded.12

BW was analysed as a continuous variable (in grams) and divided into categories of 500–1 499, 1 500–1 999, 2 000–2 750, 2 751–3 250, 3 251–3 750, 3 751–4 250, 4 251–5 500, 5 501–6 150 g, which were chosen to minimise the effects of digit preference.13

Information on gestational age is recorded in the MBR but not in the CSHRR. BW is strongly associated with gestational age, and we wanted to explore if reported BW varied by gestational age. We grouped gestational age into term categories (preterm: before 37 weeks, early term: 37 0/7 weeks to 38 6/7 weeks, full term: 39 0/7 weeks to 40 6/7 weeks, late term: 41 0/7 weeks to 41 6/7 weeks, post-term: 42 0/7 weeks and beyond).14

On the basis of measured values of height and weight taken at the examination when the BW value was reported, we calculated a body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) for each child. Each child's weight status (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obesity and morbid obesity) was classified using age-specific and sex-specific BMI cut-offs issued by the International Obesity Task Force.15

Statistical analyses

To assess if children who were missing BW information differed from those who had it in regard to sex and BW (from the other register), comparisons were made using t tests and χ2 tests. Likelihood ratio tests were used to evaluate if the association between BW in the two registers could be described linearly or exponentially.

Scatter plots were generated to compare BW values between the two registers. Comparisons of mean (SD) BWs within each register within categories of overall sex-specific time periods (1973–1978, 1979–1990, 1991) and gestational age were made using t tests. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated by time period. To graphically illustrate the agreement in BW values between the two registers, Bland-Altman plots were generated also by time period. Within the Bland-Altman plots, the limits of agreement were drawn at ±1.96SDs. To test the agreement between the two registers, we used κ coefficients for categories. The κ coefficient was not calculated for the period 1973–1978 because of the 500 g rounding in the MBR.

Using a distribution plot of differences in BW between the two registers, we identified outlying values with large discrepancies (>500 g). To examine if these participants differed from the overall population, comparisons by sex and year of birth were performed with χ2 tests.

Logistic regressions were performed to examine if differences of >100 g in BW between the two registers were associated with maternal characteristics (maternal age, civil status and parity) from the MBR and offspring characteristics (age and BMI categories at the time of recall and year of birth) obtained from the CSHRR. Interactions between parity, age at BW recall and civil status were assessed.

Results

Of 381 110 children in the CSHRR, 63 438 (16.6%) were born during 1973–1991 where the two registers overlapped and had a personal identification number. 11 971 (18.9%) children did not have information on BW in the CSHRR, and 3 832 (6.0%) did not have information on BW in the MBR. In the CSHRR, there were no statistically significant differences between children with and without BW information in regard to sex and BW (from the MBR) (all p>0.05). In the MBR, there were no statistically significant differences in BW (from the CSHRR) between children with and without BW information, but more boys (53% vs 51%, p=0.003) and fewer girls (47% vs 49%, p=0.003) had missing BW information. The final study population consisted of 47 534 children (74.9% of the eligible population) after the exclusion of children with BWs below 500 g or above 6150 g (see online supplementary figure S1).

The BW distribution was approximately normal in the MBR and the CSHRR. Digit preference was present in both registers for all time periods. Unsurprisingly, it was more apparent in the MBR than in the CSHRR during 1973–1979 when BW in the MBR was categorised in 500 g units (see online supplementary figure S2). Descriptive statistics can be seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for BW in the CSHRR and the MBR by birth year groups according to MBR procedural changes

| Birth weight (grams) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information source and period | N | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

| CSHRR | ||||||

| 1973–1991 | 47 534 | 3342 | 564 | 3350 | 500 | 6000 |

| MBR* | ||||||

| 1973–1977 | 15 807 | 3036 | 558 | 3000 | 500 | 6000 |

| 1979–1990 | 28 708 | 3346 | 555 | 3350 | 730 | 5750 |

| 1991 | 3019 | 3391 | 564 | 3416 | 634 | 5600 |

*From 1973 to 1977, BW was recorded in 500 g units in the MBR. From 1978 to 1990, BW was recorded in 10 g units, and from 1991 onwards in 1 g units.

BW, birth weight; CSHRR, Copenhagen School Health Records Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register.

Mean BW was significantly different only in the first period of the MBR (1973–1979) where the mean BW was ∼300 g higher in the CSHRR than in the MBR, most likely due to rounding procedures used in the MBR. During the two later periods (1979–1990 and 1991), mean BW was not significantly different in the two registers (table 2). We combined the two later periods in the remaining analyses because there were no notable differences between these periods and because the last period consisted of only one birth year and 3 019 children. There were no statistically significant differences between BW from the two registers when examined by maternal and offspring characteristics (all p>0.1) in the period 1979–1991 (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of BW from the CSHRR and the MBR stratified by birth year groups according to MBR procedural changes and by maternal and offspring characteristics

| N | Birth weight (grams) |

p Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSHRR |

MBR |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| 1973–1978 | ||||||

| All | 15 807 | 3323 | 555 | 3036 | 558 | <0.0001 |

| Boys | 7980 | 3382 | 568 | 3092 | 569 | <0.0001 |

| Girls | 7827 | 3263 | 535 | 2980 | 540 | <0.0001 |

| 1979–1990 | ||||||

| All | 28 708 | 3348 | 568 | 3346 | 555 | 0.67 |

| Boys | 14 782 | 3409 | 580 | 3407 | 566 | 0.67 |

| Girls | 13 926 | 3283 | 547 | 3282 | 535 | 0.86 |

| 1991 | ||||||

| All | 3 019 | 3389 | 577 | 3391 | 564 | 0.67 |

| Boys | 1540 | 3446 | 587 | 3446 | 578 | 0.98 |

| Girls | 1479 | 3330 | 560 | 3332 | 542 | 0.90 |

| Maternal characteristics† | ||||||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

| <20 | 1187 | 3252 | 543 | 3244 | 518 | 0.69 |

| 20–30 | 19 183 | 3337 | 554 | 3334 | 542 | 0.58 |

| 30–40 | 10 772 | 3387 | 592 | 3388 | 579 | 0.87 |

| 40–50 | 582 | 3401 | 603 | 3406 | 587 | 0.89 |

| ≥50 | 3 | 3292 | 525 | 3290 | 524 | 0.99 |

| Civil status | ||||||

| Married | 16 533 | 3369 | 576 | 3367 | 559 | 0.68 |

| Divorced | 1 970 | 3320 | 593 | 3321 | 584 | 0.98 |

| Not married | 13 224 | 3335 | 555 | 3334 | 547 | 0.90 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1 | 17 219 | 3308 | 555 | 3304 | 544 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 10 101 | 3400 | 575 | 3402 | 561 | 0.84 |

| 3 | 2976 | 3403 | 582 | 3402 | 559 | 0.99 |

| 4 | 892 | 3439 | 623 | 3430 | 604 | 0.76 |

| 5 | 332 | 3422 | 589 | 3441 | 566 | 0.68 |

| ≥6 | 207 | 3436 | 626 | 3453 | 614 | 0.78 |

| Offspring characteristics† | ||||||

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 1979–81 | 6607 | 3322 | 565 | 3322 | 552 | 0.99 |

| 1982–84 | 6248 | 3306 | 577 | 3305 | 565 | 0.91 |

| 1985–87 | 7591 | 3344 | 566 | 3341 | 550 | 0.75 |

| 1988–91 | 11 281 | 3401 | 565 | 3399 | 554 | 0.78 |

| Age at recall (years) | ||||||

| 5–6 | 2984 | 3381 | 556 | 3379 | 541 | 0.87 |

| 6–6.5 | 9662 | 3363 | 563 | 3362 | 550 | 0.90 |

| 6.5–7 | 10 410 | 3355 | 564 | 3354 | 554 | 0.93 |

| 7–8 | 7245 | 3327 | 582 | 3323 | 565 | 0.65 |

| >8 | 1316 | 3326 | 598 | 3328 | 579 | 0.94 |

| BMI classification at BW recall | ||||||

| Underweight | 2384 | 3100 | 592 | 3097 | 576 | 0.88 |

| Normal weight | 25 186 | 3358 | 558 | 3357 | 545 | 0.88 |

| Overweight | 3104 | 3468 | 560 | 3462 | 541 | 0.68 |

| Obese | 542 | 3514 | 614 | 3507 | 598 | 0.84 |

| Morbidly obese | 401 | 3378 | 622 | 3360 | 597 | 0.68 |

*Comparisons made by paired t tests.

†Comparisons of mean BW by maternal and offspring characteristics are only presented for the period 1979–1991.

BMI, body mass index; BW, birth weight; CSHRR, Copenhagen School Health Records Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register.

BWs in the CSHRR and the MBR were highly correlated. The lowest correlation coefficient was seen in the earliest period (0.93 (95% CI 0.92 to 0.93)) compared to the later period (0.97 (95% CI 0.97 to 0.97)); however, the correlations were still high in all periods.

From online supplementary figure S3, it can be seen that the rounding of BW in 500 g intervals in the MBR from 1973 to 1978 was very obvious. The association between BW in the two registers was linear in both periods.

The distribution of the discrepancies in BWs from the two registers can be seen in online supplementary figure S4. In the first period (1973–1978), most discrepancies were <0 g (98%), meaning that BW in the CSHRR was generally higher than BW in the MBR. A total of 95% of the discrepancies were distributed within the interval −500 to 0 g. Four-hundred and sixty six observations were distributed outside this interval with a maximal difference of 3 300 g. In the second period (1979–1991), the discrepancies were distributed almost equally around zero with 95% within the interval of ±500 g. Four-hundred and thirty eight observations were distributed outside this interval with a maximal difference of 3 514 g. For both periods, we found no differences with respect to sex (all p>0.6) among the outliers than in the rest of the population, but there was a difference in the distribution according to the year of birth (all p<0.001). However, there were no obvious patterns in the yearly distribution.

Within each register, BW was categorised into eight groups and we compared if each child was assigned to the same BW category by both registers. This was only done for the period 1979–1991 due to the rounding procedures in the MBR during 1973–1978. 94.5% of BWs were placed in the same BW category by both registers, 4.7% were placed in adjacent BW categories and only 0.1% were placed more than two BW categories apart. The κ coefficient (0.93) showed very high agreement between the two registers (table 3).

Table 3.

Cross tabulation of observations in BW categories by the CSHRR and the MBR for birth years 1979–1991

| MBR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight groups (grams) | <1500 | 1500–1999 | 2000–2750 | 2751–3250 | 3251–3750 | 3751–4250 | 4251–5500 | >5500 | Total |

| CSHRR | |||||||||

| <1500 | 181 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 212 (0.7%) |

| 1500–1999 | 8 | 332 | 26 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 372 (1.3%) |

| 2000–2750 | 1 | 18 | 2 943 | 133 | 30 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3129 (10.6%) |

| 2751–3250 | 2 | 0 | 99 | 7 954 | 317 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 8402 (28.4%) |

| 3251–3750 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 307 | 10 272 | 140 | 6 | 0 | 10 740 (36.3%) |

| 3751–4250 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 49 | 226 | 5 085 | 35 | 0 | 5397 (18.2%) |

| 4251–5500 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 28 | 79 | 1 231 | 0 | 1351 (4.6%) |

| >5500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 10 (0%) |

| Total | 192 (0.6%) | 357 (1.2%) | 3 094 (10.4%) | 8 464 (28.6%) | 10 885 (36.8%) | 5343 (18.0%) | 1 279 (4.3%) | 3 (0%) | 29 613 |

| κ | 0.93 | ||||||||

| Agreement | 94.6% | ||||||||

| Expected agreement | 26.1% | ||||||||

BW, birth weight; CSHRR, Copenhagen School Health Records Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register.

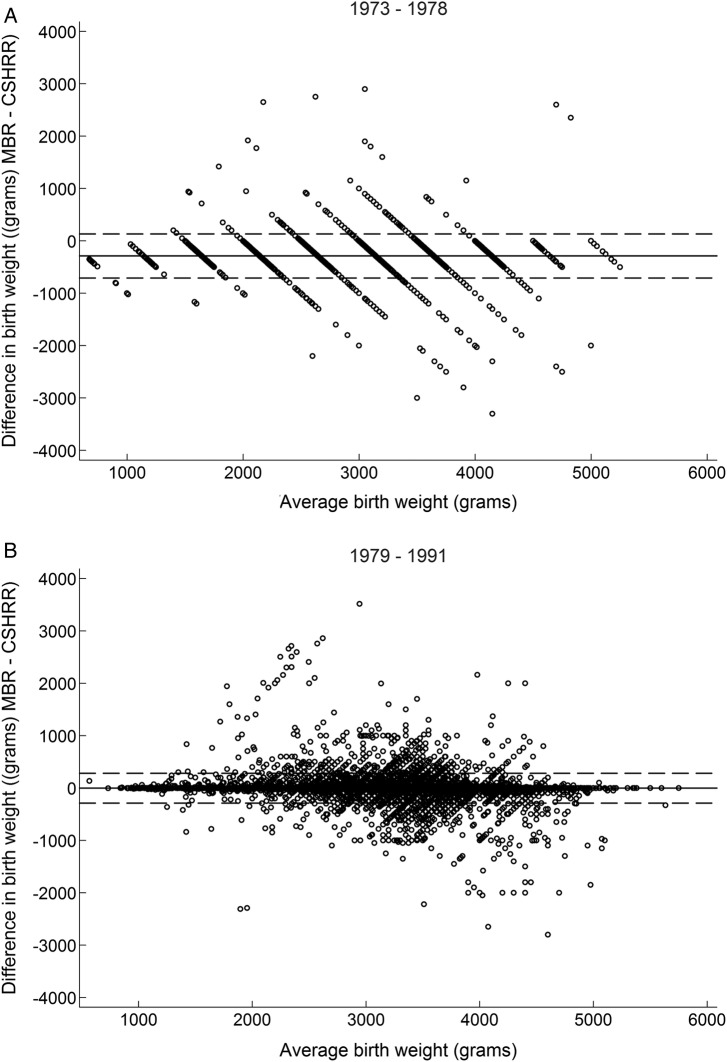

The Bland-Altman plots of the differences in BW between the two registers per average BW generally showed good agreement (figure 1). In the 1973–1978 period, the rounding procedures in the MBR were apparent. In this period, the plot illustrates that the BW reports in the MBR were, on average, lower than the ones in the CSHRR.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plots of birth weight (grams) in the CSHRR and the MBR according to MBR procedural changes. The solid line illustrates the mean difference and the dashed lines represent the ±1.96SDs. In the 1973–1978 plot, the mean difference was −287 g, with an SD of 215 g. In the 1979–1991 plot, the mean difference was −2 g, with an SD of 146 g. CSHRR, Copenhagen School Health Records Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register.

In the 1979–1991 period, the Bland-Altman plot did not reveal any systematic patterns of deviations between BWs in the two registers. For the majority of BWs (n=30 528, 96.2%), the difference between the two registers fell within the range of −287 to 284 g (corresponding to±1.96 SDs, indicated by the dashed lines in figure 1). Few values fell above these limits (n=584, 1.8%) and few fell below (n=615, 1.9%).

In the period 1973–1978, the mean BW within term categories was significantly different in the two registers (see online supplementary table S1). In the period 1979–1991, none of the BWs were significantly different by gestational age categories. There was a statistically significant increasing trend in BW by term status; however, the SDs within each of these categories overlapped.

Results from the bivariate logistic regressions of differences in BW of >100 g showed that the odds of a discrepancy increased with younger maternal age and higher parity (table 4). Compared with married women, divorced and non-married women had lower odds of a discrepancy. The odds of a discrepancy did not show a discernible pattern by year of the child's birth. Compared with children who had their BW reported at 6.5–7 years of age, those who had it reported at the youngest ages (5–6 years) and older ages had a higher odds of a discrepancy. Results from the multivariate logistic regressions showed the same associations for maternal age, civil status, parity and the child's age when the BW was reported. No statistically significant interactions among these characteristics were identified.

Table 4.

OR (95% CI) of BW discrepancy >100 g between BW from the CSHRR and the MBR stratified by maternal and offspring characteristics for the birth years 1979–1991

| OR of BW difference >100 g |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate model |

Multivariable model |

|||||||

| N | OR | 95% CI |

N | OR | 95% CI |

|||

| Maternal age | ||||||||

| <20 years | 1187 | 1.22 | 0.91 | 1.63 | 1 185 | 1.64 | 1.21 | 2.20 |

| 20 ≤years <30 | 19 183 | Reference | 19 114 | Reference | ||||

| 30 ≤years <40 | 10 772 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.37 | 10 736 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 1.04 |

| 40 ≤years <50 | 582 | 1.74 | 1.22 | 2.47 | 579 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.34 |

| ≥50 years | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Civil status | ||||||||

| Married | 16 533 | Reference | 16 469 | Reference | ||||

| Divorced | 1970 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 1.01 | 1 965 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| Not married | 13 224 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 13 180 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.89 |

| Parity | ||||||||

| 1 | 17 219 | Reference | 17 154 | Reference | ||||

| 2 | 10 101 | 1.85 | 1.62 | 2.11 | 10 073 | 1.84 | 1.60 | 2.12 |

| 3 | 2976 | 2.62 | 2.20 | 3.11 | 2 963 | 2.60 | 2.15 | 3.14 |

| 4 | 892 | 3.05 | 2.33 | 3.98 | 890 | 2.92 | 2.19 | 3.88 |

| 5 | 332 | 4.64 | 3.24 | 6.64 | 329 | 4.44 | 3.05 | 6.47 |

| ≥6 | 207 | 5.97 | 3.96 | 8.98 | 205 | 5.73 | 3.73 | 8.82 |

| Offspring characteristics* | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boy | 16 322 | Reference | 16 257 | Reference | ||||

| Girl | 15 405 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 15 357 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 1.21 |

| Year of birth | ||||||||

| 1979–81 | 6607 | Reference | 6 598 | Reference | ||||

| 1982–84 | 6248 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 1.03 | 6 228 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.07 |

| 1985–87 | 7591 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 7 566 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.95 |

| 1988–91 | 11 281 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 11 222 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 1.04 |

| Age at BW recall (years) | ||||||||

| 5–6 | 2984 | 1.55 | 1.28 | 1.88 | 2 984 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.67 |

| 6–6.5 | 9662 | 1.0 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 9 660 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.13 |

| 6.5–7 | 10 410 | Reference | 10 410 | Reference | ||||

| 7–8 | 7245 | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.38 | 7 245 | 1.21 | 1.03 | 1.42 |

| >8 | 1316 | 1.81 | 1.41 | 2.33 | 1 315 | 1.68 | 1.30 | 2.16 |

| BMI category at BW recall | ||||||||

| Underweight | 2 384 | 1.0 | 0.80 | 1.24 | 2 384 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.19 |

| Normal weight | 25 186 | Reference | 25 185 | Reference | ||||

| Overweight | 3 104 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 1.19 | 3 103 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 1.25 |

| Obese | 542 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 1.31 | 541 | 1.08 | 0.68 | 1.74 |

| Morbidly obese | 401 | 1.23 | 0.77 | 1.96 | 401 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.19 |

*Information obtained from the CSHRR. BW, birth weight; CSHRR, Copenhagen School Health Records Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register.

Discussion

We found that reports of BWs in the CSHRR agreed very well with the recorded BWs in the MBR. The MBR recorded BW in 500 g units from 1973 to 1978, which was obvious in our results and made the agreement between the two registers poorer than in the remaining study period.

We used several different methods to compare BW in the two registers. Whether BW was compared continuously or categorically, the message was the same—there was a high degree of agreement between the two. We found a high correlation between the MBR and the CSHRR, especially in the period after 1978 (0.97), which is similar to what other validation studies have found (0.97–0.98).6–8 In total, 94.5% of BWs were placed in the same BW category by the two registers and there were no discernible patterns in the misclassifications.

Other studies have also reported agreement of BW in categories, but there are large differences in the range of the BW categories, the methods used and the nationalities of the populations. The definition of BW groups influences the degree of agreement whereby smaller groups increase the likelihood of misclassification. However, the agreement was high irrespective of the BW groups used. In another Danish study, the BW was categorised as low, normal and high, and the agreement of classification was 98%.6 Among Israeli mothers, approximately 80% recalled their children's BW correctly within 500 g BW categories.9 In a study of American and Canadian mothers, the agreement was 93% using four BW categories of <3, 3–3.5, 3.5–4 and >4 kg.7 Another study of American mothers showed that the sensitivity ranged from 90.3 to 93.6% and that the specificity ranged from 97.8% to 99.3% when BW groups were defined as above and below different BW values (1.5, 2, 2.5, 3.5 and 4 kg).8

One of the major strengths of this study is that the MBR and the CSHRR are based on large unselected populations that minimise the risk of selection bias. One limitation of the CSHRR is the lack of information on child characteristics like socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors that could have been included in the analyses and potentially could have predicted discrepancies.10 The major limitation of the MBR is the rounding procedure used from 1973 to 1978.11 The analyses were restricted to BW values from 500 to 6150 g to avoid overtly erroneous values. A comparison of BW values based on gestational age categories (taken from the MBR) did not reveal any significant differences in the 1978–1991 period, suggesting that these BW values are reasonable given the infant's gestational age.

Although BW was most likely reported by the mother in the CSHRR during the years included in this study, it is a possibility that it was reported by the father or another adult with parental responsibility. In Copenhagen, each child was issued an infancy health book in which BW was recorded by the visiting health nurse shortly after delivery. These books were commonly used as a continuous health record for children, so it is possible that some parents either used this book when filling in the questionnaire or brought it with them to the examination, thus contributing to the high agreement between BW values in the CSHRR and the MBR. In the CSHRR, we have no indications of the source of the BW, and therefore we do not know if it was the majority of parents who brought the book or not. Another possible explanation is that parents (and mothers in particular) remember their children's BW very well. BW is typically reported to family and friends after the birth of the child and this might aid memorisation. BW may also have a special psychological importance that enables parents to accurately remember their child's BW.

In the present study, BWs were obtained at the school entry examination, which occurred when the children were aged 5–7 years with a few exceptions of older children who entered the register when they transferred from other schools. Other studies had other time frames ranging from 9–18 months to 6–18 years from birth to recall, but the overall conclusion has been that mothers seem to recall their children's BW very well irrespective of how much time has passed since.5–9 Our results fit well with these findings, even though we cannot be certain of whether a mother or other adult with parental responsibility reported the BW.

We found that parity and maternal civil status influenced the odds of having a discrepancy between BW in the two registers, where the odds increased with parity and were reduced among non-married women. The pattern we observe for marital status most likely reflects that many of the unmarried mothers did have partners, and that in the Danish population it is not always an indicator of a low socioeconomic position. The child's age at recall was also associated with a discrepancy; the odds of a discrepancy were the lowest when the age at recall was between 6 and 8 years compared to <6 or >8 years.

Other studies have also investigated the ability to recall BW according to various maternal characteristics.5–8 Two studies showed higher risks of a discrepancy >100 g among non-Caucasian women and women who have given birth previously compared with Caucasian and primiparous women, respectively.5 6 One of these studies also found that unemployed women remembered their child's BW less well as compared with working women, and that the lower the BW of the child, the higher was the risk of a discrepancy.5 Another study showed that mothers with less than a high school education had a higher risk of discrepancy between recalled and recorded BW.8 In contrast, another study investigated the ability to recall BW by maternal education, age and race, household income, time from delivery to maternal recall, and birth order of the child, and found no significant differences across any of these demographic subgroups.7

We examined BW recall during the birth years of 1973–1991 among Danes, and it is a possibility that recall may have changed since then or that it differs depending on which population is being investigated. In our study, we only had the possibility to look into recall ability according to maternal age, parity, civil status, offspring age and body size at recall and year of birth. Nonetheless, we had an unselected population where all socioeconomic groups were represented; the generalisability of our results should apply to a general Danish population.

Medical birth records are not always available because of the studied time period or because retrieving records is too labour demanding; as such, recalled information might be the only source of BW. In such cases, a validation study like the present one is useful for demonstrating the accuracy of the BW data. Previous and future research based on the CSHRR will gain from the present conclusion that reports of BW in the CSHRR agreed very well with BW records in the MBR. Other cohorts or registers from similar populations can, however, also draw on the present conclusion that maternal reports of BWs are accurate and can be used as a reasonable substitute when medical birth records are unavailable.

Conclusion

Overall, reported BWs in the CSHRR agreed very well and accurately with recorded values from medical birth records, suggesting that these values are valid. Discrepancies in BW were more often seen among married women, women with several children, and among children who were below 6 or above 8 years at recall. These results suggest that research on associations between BW and adult onset diseases will not be biased by the use of information on BW that is obtained during childhood from school health records.

Footnotes

Contributors: TIAS and JLB conceived the research idea; CBJ and JLB designed the research; CBJ performed statistical analysis; CBJ, MG, BH, TIAS and JLB interpreted the results, CBJ drafted the manuscript and MG, BH, TIAS and JLB commented on it; CBJ and JLB had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The project was funded by the Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation, the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Higher Education, under the instrument “Strategic research projects” and by a research grant from the Danish PhD School of Molecular Metabolism funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. This research was financially supported by the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement no. 281 419, childgrowth2cancer awarded to JLB. The supporting bodies for this project had no role in the design, implementation, analysis and interpretation of the data presented.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Access and linkage permission was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2012-41-1156).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Risnes KR, Vatten LJ, Baker JL et al. Birthweight and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:647–61. 10.1093/ije/dyq267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG. From the cradle to the labor market? The effect of birth weight on adult outcomes. Q J Econ 2007;122:409–39. 10.1162/qjec.122.1.409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers I. The influence of birthweight and intrauterine environment on adiposity and fat distribution in later life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:755–77. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology or pathophysiology? Physiol Rev 2014;94:1027–76. 10.1152/physrev.00029.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tate AR, Dezateux C, Cole TJ et al. Factors affecting a mother's recall of her baby's birth weight. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:688–95. 10.1093/ije/dyi029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adegboye AR, Heitmann B. Accuracy and correlates of maternal recall of birthweight and gestational age. BJOG 2008;115:886–93. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2438372&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed 14 Aug 2014). 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01717.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson JE, Shu XO, Ross JA et al. Medical record validation of maternally reported birth characteristics and pregnancy-related events: a report from the Children's Cancer Group. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:58–67. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8982023 (accessed 14 Aug 2014). 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucia VC, Luo Z, Gardiner JC et al. Reports of birthweight by adolescents and their mothers: comparing accuracy and identifying correlates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2006;20: 520–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gofin R, Neumark YD, Adler B. Birthweight recall by mothers of Israeli children. Public Health 2000;114:161–3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10878741 (accessed 14 Aug 2014). 10.1016/S0033-3506(00)00328-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Andersen I et al. Cohort profile: the Copenhagen School Health Records Register. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:656–62. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2722813&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed 20 Mar 2014). 10.1093/ije/dyn164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knudsen LB, Olsen J. The Danish Medical Birth Registry. Dan Med Bull 1998;45:320–3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9675544 (accessed 13 May 2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milsgaard M.2013. Ny rekord på fødestuen. Fødte en gigantisk baby. [New record in the delivery room. Gave birth to a gigantic baby.]. Ude og Hjemme. http://www.udeoghjemme.dk/Artikler/Kaerlighed-og-sorg/2013/07/31-foedte-en-gigantisk-baby.aspx.

- 13.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sørensen TI. Weight at birth and all-cause mortality in adulthood. Epidemiology 2008;19:197–203. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816339c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.No authors listed]. ACOG Committee Opinion No 579: definition of term pregnancy. Obs Gynecol 2013;122:1139–40. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437385.88715.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:284–94. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]