Abstract

Fusarium goolgardi, isolated from the grass tree Xanthorrhoea glauca in natural ecosystems of Australia, is closely related to fusaria that produce a subgroup of trichothecene (type A) mycotoxins that lack a carbonyl group at carbon atom 8 (C-8). Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that F. goolgardi isolates produce type A trichothecenes, but exhibited one of two chemotypes. Some isolates (50%) produced multiple type A trichothecenes, including 4,15-diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS), neosolaniol (NEO), 8-acetylneosolaniol (Ac-NEO) and T-2 toxin (DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype). Other isolates (50%) produced only DAS (DAS chemotype). In the phylogenies inferred from DNA sequences of genes encoding the RNA polymerase II largest (RPB1) and second largest (RPB2) subunits as well as the trichothecene biosynthetic genes (TRI), F. goolgardi isolates were resolved as a monophyletic clade, distinct from other type A trichothecene-producing species. However, the relationships of F. goolgardi to the other species varied depending on whether phylogenies were inferred from RPB1 and RPB2, the 12-gene TRI cluster, the two-gene TRI1-TRI16 locus, or the single-gene TRI101 locus. Phylogenies based on different TRI loci resolved isolates with different chemotypes into distinct clades, even though only the TRI1-TRI16 locus is responsible for structural variation at C-8. Sequence analysis indicated that TRI1 and TRI16 are functional in F. goolgardi isolates with the DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype, but non-functional in isolates with DAS chemotype due to the presence of premature stop codons caused by a point mutation.

Keywords: DNA sequence, phylogenetics, evolution, mycotoxins metabolite profile

1. Introduction

Fusarium is an economically significant fungal genus with many species that cause crop disease and mycotoxin contamination. Agriculturally important Fusarium species have also been isolated from non-cultivated ecosystems, often associated with asymptomatic plants [1,2,3]. Fusarium goolgardi is a recently described species isolated from Xanthorrhoea glauca (grass tree) in natural ecosystems of New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Isolates were recovered from both asymptomatic (Khancoban, Tumut and Yass regions) and symptomatic plants (Bungonia State Conservation Area) [4], suggesting the possible involvement of F. goolgardi in the observed disease symptoms.

A closely related species, F. palustre, has been implicated in sudden dieback of smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) in natural ecosystems in North America [5]. Fusarium palustre and F. goolgardi are both members of the F. sambucinum species complex (FSAMSC), a lineage of Fusarium that produces trichothecene mycotoxins. Trichothecenes are known to cause contamination of cereal crops and contribute to plant pathogenesis [6,7,8]. Whether F. goolgardi is a trichothecene producer has yet to be investigated.

Trichothecenes are products of sesquiterpenoid metabolism, produced by some species of Fusarium and other genera in the order Hypocreales [9]. All trichothecenes have the core 12, 13-epoxytrichothec-9-ene (EPT) structure. However, different trichothecene analogues have different patterns of substitution around this core structure. Fusarium trichothecenes are often categorised as either type A or type B. Type A trichothecenes have a hydroxyl group (e.g., neosolaniol, NEO), an ester function (e.g., T-2 toxin) at carbon atom 8 (C-8) of the EPT molecule, or no functional group (e.g., 4, 15-diacetoxyscirpenol, DAS) [10,11]. By contrast, all type B trichothecenes have a carbonyl group at C-8. Type A trichothecenes are highly toxic to animals, causing immune disorders, growth retardation, weight loss, pathological changes in liver cells, and death [12]. Furthermore, these toxins can inhibit mitosis and synthesis of nucleic acids and proteins, as well as induce apoptosis [13,14]. In plants, DAS and T-2 toxin can cause chlorosis and inhibit coleoptile and root elongation [15].

In addition to F. palustre, F. goolgardi is closely related to the type A trichothecene-producing species F. armeniacum, F. langsethiae, F. sibiricum and F. sporotrichioides [4]. Molecular genetics and biochemical analyses have revealed that in F. sporotrichioides, type A trichothecene biosynthetic genes (TRI) occur at three loci [10,11]. The first locus is the 12-gene TRI cluster that includes the terpene synthase gene (TRI5), P450 monooxygenase genes (TRI4, TRI11, and TRI13), acyl transferase genes (TRI3 and TRI7), and an esterase gene (TRI8). Collectively, TRI cluster genes are responsible for synthesis of the EPT molecule and one or two structural modifications at C-3, C-4 and C-15 [11,16]. The second locus consists of the acetyl transferase gene TRI101, which is responsible for acetylation of the hydroxyl group at C-3 [9,11]. The third locus consists of the P450 monooxygenase gene TRI1 and the acyl transferase gene TRI16, which are responsible for hydroxylation and acylation of C-8 respectively. Together, TRI1 and TRI16 are responsible for structural variation at C-8 of type A trichothecenes [11].

Studies of both type A and B trichothecene-producing species indicate that the evolutionary history of the TRI loci is complex and does not always reflect the evolution of species in which the loci occur [17,18]. Analysis of the F. graminearum species complex (FGSC) indicates that the lack of correlation between species phylogenies and phylogenies based on some TRI cluster genes is a result of balancing selection of ancestral TRI cluster alleles that confer different type B trichothecene production phenotypes (chemotypes) [17,18,19,20]. Another study revealed a lack of correlation between species phylogenies and TRI1-TRI16-based phylogenies [9]. Furthermore, the organization of TRI genes in a second lineage of trichothecene-producing fusaria, the F. incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC), suggests a complex evolutionary history of these genes that includes loss, non-functionalization, and translocation within and between TRI loci [9].

The objective of this study was to determine whether F. goolgardi could produce trichothecenes and to assess the phylogenetic relationships of its TRI gene sequences to those in closely related type A trichothecene-producing species. The results revealed two trichothecene chemotypes, provided evidence for the genetic basis of the chemotypes, and suggested that chemotype differences could be representative of different populations within F. goolgardi.

2. Results

2.1. Mycotoxin Analysis

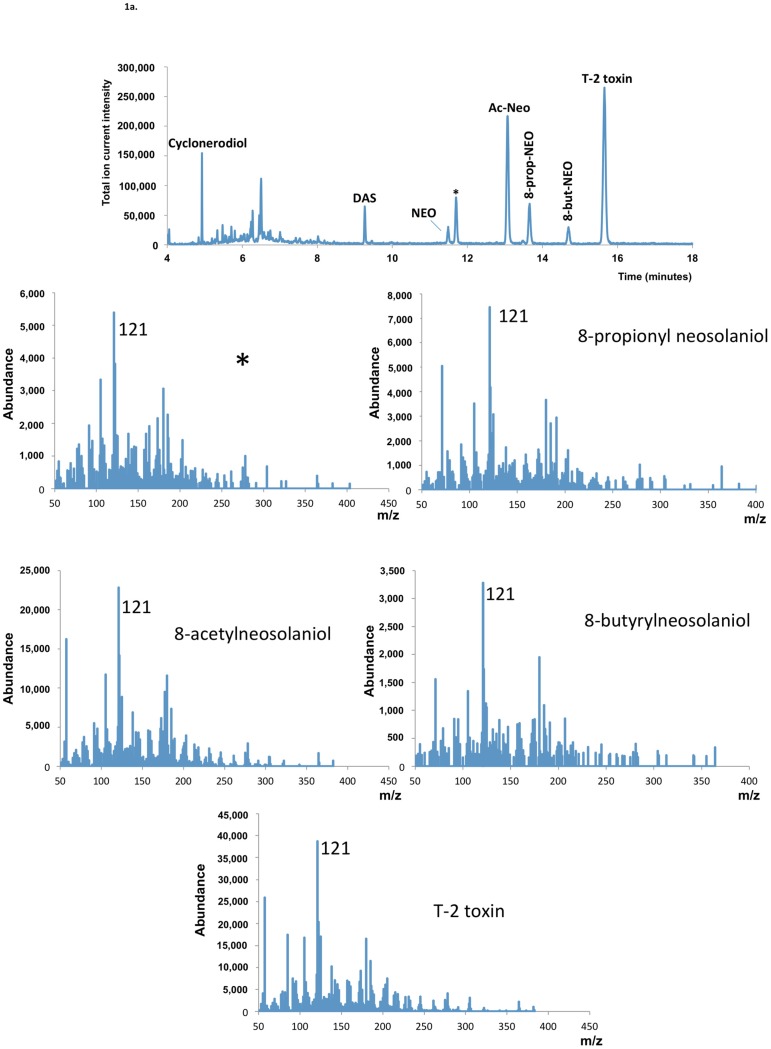

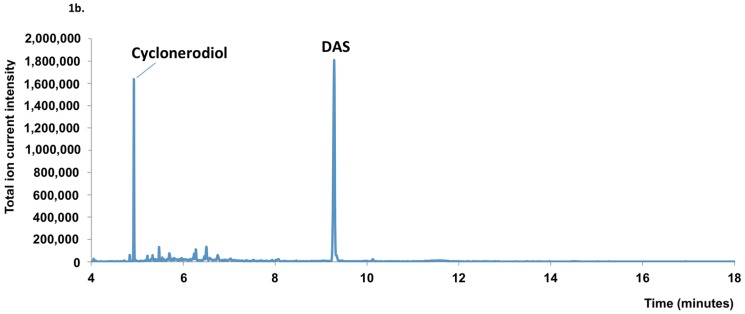

GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of trichothecenes in GYEP culture extracts of all F. goolgardi strains examined. The analysis indicated that strains RBG5411, RBG5417, RBG5419, and RBG5420 produced the type A trichothecenes DAS, NEO, 8-acetylneosolaniol and T-2 toxin (=8-isovaleryl neosolaniol) (DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype), whereas isolates RBG5421, RBG5422, RBG6914, and RBG6915 produced only DAS (DAS chemotype) (Figure 1). Neither trichothecenes with a carbonyl group at C-8 (i.e., type B trichothecenes such as deoxynivalenol or nivalenol) nor HT-2 toxin were detected in cultures of any of the F. goolgardi isolates. The four isolates with the DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype were from the Bungonia, Khancoban or Tumut region, whereas the four isolates with the DAS chemotype were all from the Yass region (Table S1). Isolates with the DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype also produced 8-propionylneosolaniol, 8-butyrylneosolaniol, and an additional metabolite, which was another type A 8-acylneosolaniol derivative. The other Fusarium species used in this study, including F. palustre, produced DAS, NEO, Ac-NEO, and T-2 toxin (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Representative Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS) data generated of F. goolgardi culture extracts. (a) GC/MS of the F. goolgardi RBG5420, representing 4,15-diacetoxyscirpenol-neosolaniol-T-2 toxin (DAS-NEO-T2) chemotype; (b) GC/MS of the F. goolgardi RBG5421, representing DAS chemotype. * indicates putative 8-acylneosolaniol with MS spectrum similar to those of 8-acetylneosolaniol, 8-propionylneosolaniol, 8-butyrylneosolaniol and T-2 toxin (= 8-isovalerylneosolaniol), i.e., m/z 121 base peak, and m/z 364 and 382 ions).

2.2. Sequence Analysis

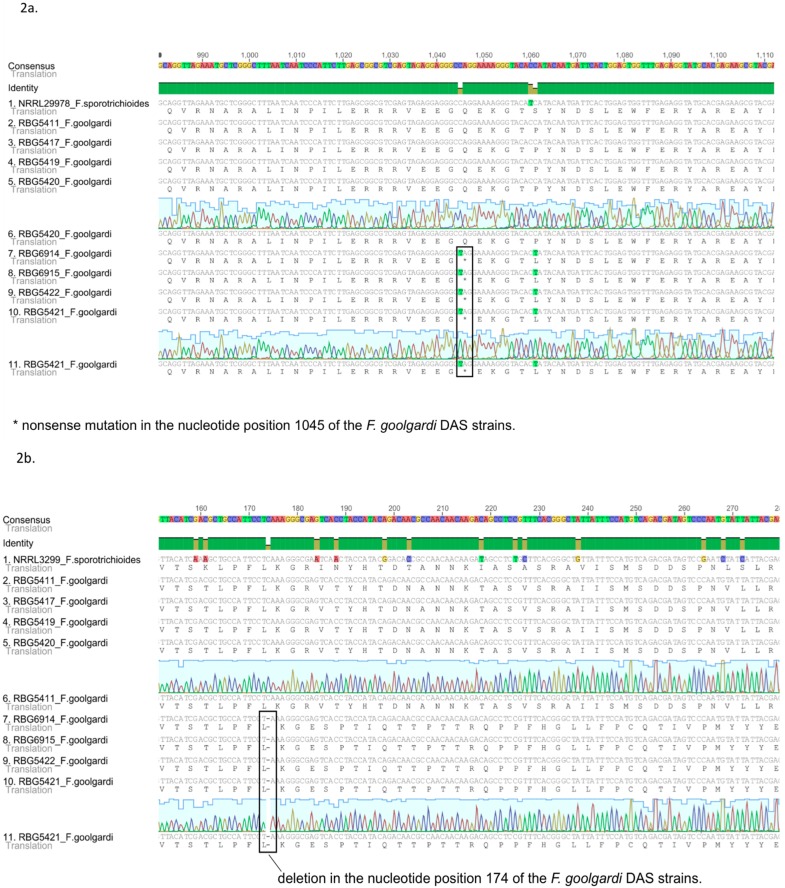

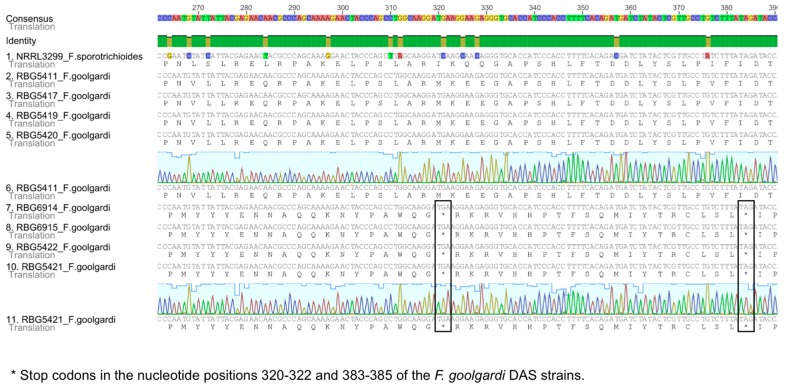

Nucleotide sequence data generated in this study for selected TRI genes from F. goolgardi were aligned against reference sequences from F. sporotrichioides strains NRRL 3299 and NRRL 29978. No major differences were observed in the coding region sequences of the two species for the cluster genes TRI3, TRI4, TRI5, TRI7, TRI8, TRI11, and TRI13 or for TRI101. However, sequences of TRI1, and TRI16 in F. goolgardi isolates with the DAS chemotype exhibited significant differences from the F. sporotrichioides sequences. These isolates exhibited a C-to-T transition that resulted in a premature stop codon (nonsense mutation) in the fourth exon at position 1045 of the TRI1 coding region (Figure 2). The TRI16 coding region of DAS-chemotype isolates exhibited a single-nucleotide deletion at position 174, which caused a frame shift mutation and introduced premature stop codons at positions 320–322 and 383–385 of this gene (Figure 2). TRI1 and TRI16 orthologs from the other Fusarium species examined, including the F. goolgardi DAS-NEO-T2 strains, did not exhibit these or any other nonsense or frame shift mutations.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the nucleotides and the predicted amino acid sequences of TRI1 and TRI16 for F. goolgardi. (a) Alignment of the nucleotide and the predicted amino acid sequences of TRI1 from F. goolgardi DAS-NEO-T2 and DAS lineages and F. sporotrichioides NRRL 29978; (b) Alignment of the nucleotide and the predicted amino acid sequences of TRI16 from F. goolgardi DAS-NEO-T2 and DAS lineages and F. sporotrichioides NRRL 3299.

Divergence was observed between isolates of F. goolgardi with the DAS or DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype in the sequences of the TRI cluster genes, TRI1, TRI16, and TRI101. The number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) observed in the two groups of isolates was 23 for the combined sequences of the TRI cluster genes examined, four for TRI101 and two for TRI1. TRI16 had a single deletion, with no evidence of SNPs.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.3.1. RNA Polymerase II Largest (RPB1) and Second Largest (RPB2) Subunits

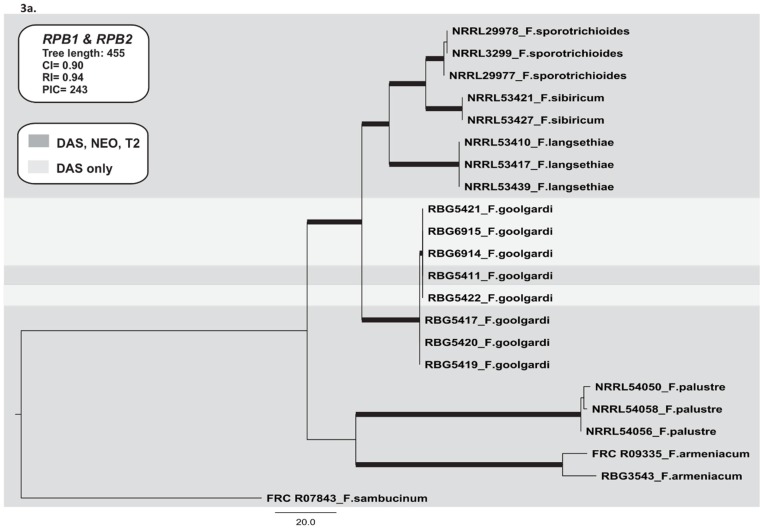

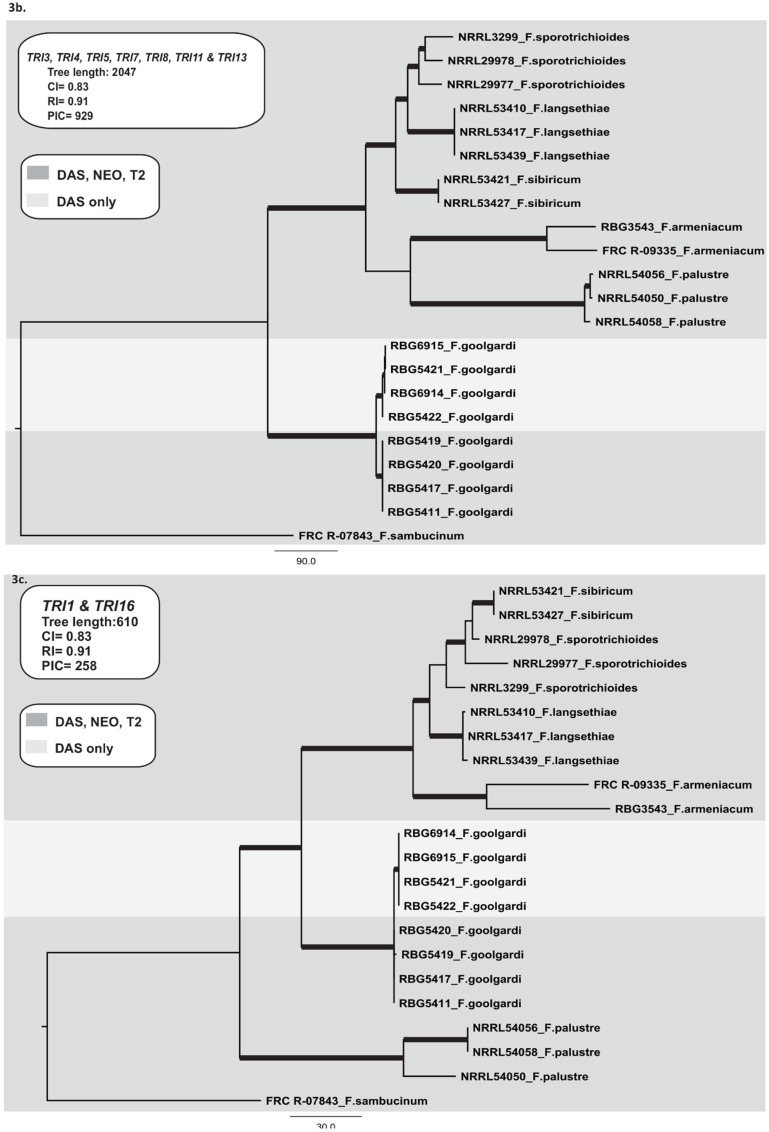

We used sequences of the RNA polymerase genes RPB1 and RPB2 to infer a species phylogeny of Type A trichothecene-producing fusaria. The RPB1 and RPB2 data set consisted of 22 taxa and 3260 nucleotides with 243 parsimony informative characters (PICs). The analysis resulted in two most parsimonious trees (CI = 0.90, RI = 0.94) (Figure 3a). No major topological variations were detected between trees derived from Neighbour-Joining, Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. The species phylogeny was composed of four main lineages: (i) F. armeniacum, (ii) F. goolgardi, (iii) F. langsethiae-F. sibiricum-F. sporotrichioides and (iv) F. palustre. The closest relative of F. goolgardi was the F. langsethiae-F. sibiricum-F. sporotrichioides lineage. Within the F. goolgardi clade, a lineage was resolved that consisted of the four isolates with the DAS chemotype and a single isolate with a DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype (Figure 3a). The monophyly of this lineage was not rejected by the SH test (p > 0.05) and each lineage was supported by both BPP and MPBS.

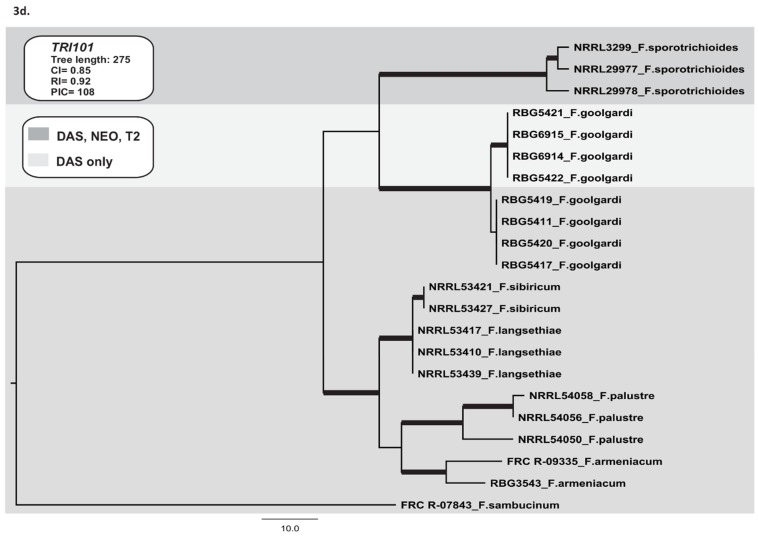

Figure 3.

Maximum parsimony trees inferred in this study. (a) One of two most-parsimonious trees for the combined RPB1 and RPB2 data sets, including 22 isolates with F. sambucinum as the outgroup; (b) The most parsimonious tree for the combined TRI core gene cluster (TRI3, TRI4, TRI5, TRI7, TRI8, TRI11, and TRI13), including 22 isolates with F. sambucinum as the outgroup; (c) The most parsimonious tree for the combined TRI1 and TRI16 data set, including 22 isolates with F. sambucinum as the outgroup; (d) One of ten most-parsimonious trees for TRI101. Bootstrap intervals (10,000 replications) greater than 70% and Bayesian posterior probabilities greater than 0.90 are indicated as branches in bold in the phylogenetic trees. The type A trichothecene chemotypes (DAS and DAS-NEO-T2) are indicated by light grey (DAS lineage) and dark grey (DAS-NEO-T2 lineages).

2.3.2. TRI Gene Cluster

For analysis of TRI cluster genes, sequence data for individual genes were concatenated. The resulting data set consisted of 22 taxa and 6750 nucleotides with 929 PICs. The analysis resulted in one most parsimonious tree (CI = 0.83, RI = 0.91) (Figure 3b). No major topological variation was detected between trees derived from Neighbour-Joining, Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. The phylogeny included the four main lineages observed in the species phylogeny. However, in contrast to the species phylogeny, the TRI cluster phylogeny included a well-supported clade consisting of F. armeniacum, F. palustre and the F. langsethiae-F. sibiricum-F. sporotrichioides lineage, but excluded F. goolgardi. Two lineages were resolved within F. goolgardi: one consisting of only DAS-NEO-T2 strains, and the other consisting of only DAS strains. There were no major topological differences among trees generated with individual TRI cluster genes (TRI3, TRI4, TRI5, TRI7, TRI8, TRI11, and TRI13). For the combined data set, SH test did not reject the monophyly of the lineages (p > 0.05) for each phylogeny, and all lineages were supported by either BPP or MPBS.

2.3.3. TRI1 and TRI16

The TRI1–TRI16 data set consisted of 22 taxa and 1933 nucleotides with 258 PICs. The analysis resulted in one most parsimonious tree (CI = 0.83, RI = 0.91) (Figure 3c). No major topological variation was detected between trees derived from Neighbour-Joining, Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. The phylogeny consisted of three major lineages: (i) F. armeniacum-F. langsethiae-F. sibiricum-F. sporotrichioides; (ii) F. goolgardi and (iii) F. palustre. In this phylogeny, F. goolgardi was resolved as a sister lineage to the F. armeniacum-F. langsethiae-F. sibiricum-F. sporotrichioides lineage. In contrast to the other phylogenies, there was no clear separation of F. sporotrichioides and F. sibiricum, and F. armeniacum was closely related to F. sporotrichioides, F. langsethiae, and F. sibiricum with both BPP and MPBS branch support (Figure 3c). A well-supported clade consisting of the four isolates with the DAS chemotype was resolved within F. goolgardi (Figure 3c). There were no major topological differences between the TRI1 and TRI16 phylogenies. The monophyly of each lineage was not rejected by the SH test (p > 0.05), and each lineage was supported by both BPP and MPBS.

2.3.4. TRI101

The TRI101 data set consisted of 22 taxa and 926 nucleotides with 108 PICs. The analysis resulted in ten most parsimonious trees (CI = 0.85, RI = 0.92) (Figure 3d). No major topological variation was detected between trees derived from Neighbour-Joining, Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. The phylogeny consisted of five lineages: (i) F. armeniacum; (ii) F. goolgardi; (iii) F. langsethiae–F. sibiricum; (iv) F. palustre, and (v) F. sporotrichioides (Figure 3d). F. langsethiae and F. sibiricum were more closely related to F. armeniacum and F. palustre, instead of F. sporotrichioides with both BPP and MPBS branch support (Figure 3d). A well-supported clade consisting of the four isolates with the DAS chemotype was resolved within F. goolgardi. In TRI101 phylogeny, the monophyly of each lineage was not rejected by the SH test (p > 0.05).

3. Discussion

A previous phylogenetic analysis resolved F. goolgardi into a lineage within the FSAMSC that includes F. armeniacum, F. langsenthiae, F. sibiricum, and F. sporotrichioides, which are among the few Fusarium species that produce the C-8 acylated, type A trichothecene T-2 toxin [4]. The results of the current study demonstrate that some isolates of F. goolgardi can produce T-2 toxin, as well as other type A trichothecenes. None of the isolates examined produced type B trichothecenes. Thus, trichothecene production in F. goolgardi is similar to its closest relatives for which data is available. The identification of the two chemotypes (DAS and DAS-NEO-T2) among isolates of F. goolgardi is unusual among T-2 toxin-producing species of the FSAMSC. Only a single chemotype has been reported for F. armeniacum, F. langsethiae, F. sibiricum and F. sporotrichioides [21,22,23,24]. However, in the more distantly related type species F. sambucinum, chemotype variation similar to that of F. goolgardi was previously reported [25]. Moreover, the F. goolgardi DAS-NEO-T2 strains also produced other compounds with mass spectra that indicate that they are other 8-acyl derivatives of NEO. Further investigation is required for complete chemical and characterization of these derivatives.

The presence of premature stop codons within the coding regions of TRI1 and TRI16 from F. goolgardi isolates with the DAS chemotype almost certainly renders the two genes nonfunctional and is consistent with the lack of production of trichothecenes with modifications at C-8. In F. sporotrichioides, TRI1 and TRI16 are responsible for hydroxylation and acylation, respectively, of type A trichothecenes at C-8 [26,27,28]. Thus a nonfunctional TRI16 in F. goolgardi should prevent acylation of the C-8 hydroxyl of trichothecenes, and a non-functional TRI1 should prevent hydroxylation of the C-8. Although a laboratory-induced point mutation responsible for alteration of a type A trichothecene chemotype in Fusarium has been reported previously [26], to our knowledge, this is the first report of a naturally occurring point mutation responsible for such an altered chemotype.

The TRI cluster, TRI-TRI16 and TRI101 phylogenies resolved isolates with the DAS chemotype into a distinct clade within F. goolgardi. A similar lineage was resolved in the RPB1 and RPB2 phylogeny, but it included one isolate with the DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype. A previous study showed that phylogenies inferred from TRI cluster genes and TRI101 are correlated with the species phylogeny, but the TRI1 and TRI16 are not correlated to the species phylogeny [9]. In the current investigation, the TRI1-TRI16, and TRI101 phylogenies differed from the species phylogeny. Proctor et al. [9] have also suggested that the TRI1-TRI16 locus was the ancestral character state, with at least four different alleles for TRI1 in the ancestral trichothecene-producing Fusarium species [9]. Furthermore, TRI16 was probably functional in the ancestral Fusarium species [9], as it is more likely for a gene to lose functionality than for a gene with multiple deletions and nonsense mutations to become functional [9]. If this is the case, the TRI1-TRI16 locus in F. goolgardi isolates with the DAS-NEO-T2 chemotype is ancestral to the locus in isolates with the DAS chemotype. The results also suggest that further polymorphisms have occurred in the DAS lineage, possibly causing loss of functionality in TRI1 and TRI16. Interestingly, both genes had deleterious mutations within the DAS lineage of F. goolgardi. The likely scenario that caused these mutations within TRI1-TRI16 locus is difficult to determine; however, genome sequencing of F. goolgardi may shed more light on this observation.

The F. goolgardi DAS lineage was recovered from the Yass region, whilst the DAS-NEO-T2 isolates were recovered from the Bungonia, Khancoban and Tumut regions. Despite the proximity among these regions (about 100 km distance between each region), two chemotypes were observed. This could be indicative of a population subdivision associated with chemotype differences in F. goolgardi; however, further surveys in NSW and other regions of Australia where X. glauca occurs are required for a better understanding of F. goolgardi chemotype and population diversity. In Bungonia, F. goolgardi was associated with decline symptoms of X. glauca [4]. Considering that fungal toxins contribute to plant pathogenesis [29] and that trichothecene production contributes to the virulence of some fusaria on wheat and maize [30,31], studies should be conducted to evaluate if F. goolgardi and type A trichothecenes are involved in X. glauca decline in Bungonia National Park. However, it is important to highlight that several environmental factors may influence mycotoxin biosynthesis [32] and various molecules can be involved in Fusarium pathogenicity [33,34]. Consequently, pathogenicity tests in X. glauca and the characterization of patterns of directional selection in the TRI genes would aid in answering these questions.

The findings from this study provide evidence for the genetic basis of trichothecene chemotype variation in F. goolgardi, but further investigations are required to verify whether the two chemotypes represent two distinct populations of the fungus. Furthermore, analysis of the pathogenicity and trichothecene production of F. goolgardi in planta is warranted to determine whether the fungus and its ability to produce trichothecenes contribute to decline of X. glauca in natural ecosystems.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Fusarium Isolates

A total of 22 Fusarium strains representing the species F. armeniacum, F. goolgardi, F. langsethiae, F. palustre, F. sambucinum, F. sibiricum, and F. sporotrichioides of the FSAMSC were selected for analysis (Table S1). The species were selected based on their ability to produce type A trichothecenes [20] and their phylogenetic affinities to F. goolgardi [4]. The isolates were obtained from the Fusarium Research Centre (FRC); the culture collection at the Pennsylvania State University (State College, PA, USA); the Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL, Peoria, IL, USA); Agricultural Research Service culture collection (Peoria, IL, USA); and the Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG) and Domain Trust collection (Sydney, Australia).

4.2. Mycotoxin Analysis

Trichothecene production was analysed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Fusarium strains were initially grown on V-8 juice agar for seven days at 25 °C prior to GC-MS analysis. Strains were then transferred to GYEP liquid medium (5% dextrose, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.1% peptone; 20 mL in 50-mL Erlenmeyer flask) and cultivated at 28 °C in the dark at 200 rpm [35]. After seven days, 5 mL culture aliquots were extracted with 2 mL ethyl acetate, dried under nitrogen stream and re-suspended in 200 μL ethyl acetate. GC-MS analysis was performed on a Hewlett Packard 6890 gas chromatograph fitted with a HP-5MS column (30 m length × 0.25 mm internal diameter × 0.25 μm film thickness) and a 5973 mass detector. The carrier gas was helium with 20:1 split ratio and a 20 mL min−1 split flow. The column was held at 120 °C at injection, heated to 260 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min and held for 13.4 min [35]. The presence of T-2 toxin, DAS, NEO and other trichothecenes in culture extracts was determined by comparison of retention times and mass spectra of purified toxin standards.

4.3. Locus Selection

The housekeeping genes RPB1 and RPB2 were selected based on the ability to resolve inter/intra-species nodes within Fusarium using the nucleic acid sequences of these genes [4,20,36,37]. TRI genes were selected based on the trichothecene biosynthetic pathway and on the previous study by Proctor et al. [9]. Hence, the following genes were selected for this study: cluster genes (TRI3, TRI4, TRI5, TRI7, TRI8, TRI11, TRI13); as well as TRI1-TRI16 and TRI101.

4.4. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequence Analysis

Fusarium cultures were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) for 5 days at 25 °C. DNA was extracted using the FastDNA kit (Q-Biogene Inc., Irvine, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sets are shown in supplementary Table S2. PCR conditions for amplifying the partial sequences of RPB1, RPB2 [36,37] and TRI genes [9] were followed according to their respective protocols. The purified amplicons were sent to the Ramaciotti Centre for Gene Function Analysis at the University of New South Wales where DNA sequences were determined using an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences were aligned for each isolate using the multiple alignment program ClustalX v. 1.83 plug-in [38] in the software Geneious v. 5.3.6 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) [39]. The alignments were edited using the sequence alignment-editing program Geneious v. 1.83 [39] and polymorphisms were confirmed by re-examining the chromatograms.

Similarities of gene sequences detected in this study were verified against the current nucleotide sequences available in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [40]. The coding regions of the generated sequences were aligned against the annotated reference of TRI gene sequences downloaded from NCBI for verifying the presence of nonsense mutations. The sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table S1).

4.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

The combined RPB1 and RPB2 data sets were used to infer a species phylogeny. The TRI gene phylogenies for species in the FSAMSC were generated from the following combined data sets: combined TRI cluster genes TRI3, TRI4, TRI5, TRI7, TRI8, TRI11 and TRI13; combined TRI1 and TRI16 and TRI101. The data sets were combined based on gene location within the three previously described TRI loci in F. sporotrichioides [9,11] and if the monophyly at the lineage level was not rejected by the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH) test [41].

Unweighted Parsimony analysis was conducted by using heuristic search option with 1000 random addition sequences and tree bisection reconnection branch swapping in PAUP 4.0b10 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, USA) [42]. Gaps were treated as missing data. The Consistency Index (CI) and the Retention Index (RI) were calculated to indicate the amount of homoplasy present. Neighbour-Joining analysis was performed in PAUP 4.0b10 using an appropriate nucleotide substitution model determined by JModelTest (University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland) [43]. Clade stability was assessed via Maximum Parsimony Bootstrap Proportions (MPBS) in PAUP 4.0b10, using 1000 heuristic search replications with random sequence addition. The data sets were rooted with F. sambucinum as it is considered a suitable out-group [9,20]. Bayesian Likelihood analysis was used to generate Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (BPP) for consensus nodes using Mr Bayes 3.1 [44], run with a 2,000,000-generation Monte Carlo Markov chain method with a burn-in of 10,000 trees. JModelTest was used to determine the substitution evolution model for each gene data sets. The phylogenetic trees were visualised using FigTree v.1.4 (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) [45]. The SH tests performed with PAUP 4.0b10 [41,42] were used to assess the concordance between gene phylogenies [18,46]. Data sets were combined if the different type A trichothecene producing lineages were well supported with MPBS and BPP and if the monophyly at the lineage level was not rejected by the SH test. Monophyly was rejected if the constrained tree log likelihood score was significantly different from the unconstrained topology with 95% confidence level (p < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, for funding, Marcie L. Moore from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-ARS, Peoria, IL, USA) for technical support, Candice Cherk Lim and Victor I. Puno for advice and assistance.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be accessed at: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/7/11/4577/s1.

Author Contributions

Liliana O. Rocha, Matthew H. Laurence and Edward C. Y. Liew conceived the study. Liliana O. Rocha designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. Matthew H. Laurence contributed with manuscript editing and supervision of the study. Robert H. Proctor and Susan P. McCormick performed mycotoxin and sequencing data analyses, and also contributed ideas, manuscript editing and information. Brett A. Summerell and Edward C. Y. Liew supervised the overall study and edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang B., Brubaker C.L., Burdon J.J. Fusarium species and Fusarium wilt pathogens associated with native Gossypium populations in Australia. Mycol. Res. 2004;108:35–44. doi: 10.1017/S0953756203008803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley A.R., Petrovic T., Griffiths S.P., Burgess L.W., Summerell B.A. Crop pathogens and other Fusarium species associated with Austrostipa aristiglumis. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2007;36:434–438. doi: 10.1071/AP07047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrovic T., Burgess L.W., Cowie I., Warren R.A., Harvey P.R. Diversity and fertility of Fusarium sacchari from wild rice (Oryza australiensis) in Northern Australia, and pathogenicity tests with wild rice, rice, sorghum and maize. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013;136:773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0206-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurence M.H., Walsh J.L., Shuttleworth L.A., Robinson D.M., Johansen R.M., Petrovic T., Vu T.T.H., Burgess L.W., Summerell B.A., Liew E.C.Y. Six novel species of Fusarium from natural ecosystems in Australia. Fungal Divers. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0337-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmer W.H., Marra R.E. New species of Fusarium associated with dieback of Spartina alterniflora in Atlantic salt marshes. Mycologia. 2011;103:806–819. doi: 10.3852/10-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eudes F., Comeau A., Rioux S., Collin J. Impact of trichothecenes on Fusarium head blight (Fusarium graminearum) development in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum) Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2001;23:318–322. doi: 10.1080/07060660109506948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desjardins A.E., Hohn T.M. Mycotoxins in plant pathogenesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:147–152. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.2.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuzick A., Urban M., Hammond-Kosack K. Fusarium graminearum gene deletion mutants map1 and tri5 reveal similarities and differences in the pathogenicity requirements to cause disease on Arabidopsis and wheat floral tissue. New Phytol. 2008;177:990–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proctor R.H., McCormick S.P., Alexander N.J., Desjardins A.E. Evidence that a secondary metabolic biosynthetic gene cluster has grown by gene relocation during evolution of the filamentous fungus Fusarium. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;74:1128–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura M., Tokai T., Takahashi-Ando N., Ohsato S., Fujimura M. Molecular and genetic studies of Fusarium trichothecene biosynthesis: Pathways, genes, and evolution. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:2105–2123. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormick S.P., Stanley A.M., Stover N.A., Alexander N.J. Trichothecenes: From simple to complex mycotoxins. Toxins. 2011;3:802–814. doi: 10.3390/toxins3070802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J., Jing L., Yuan H., Peng S. T-2 toxin induces apoptosis in ovarian granulosa cells of rats through reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Toxicol. Lett. 2011;202:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torp M., Langseth W. Production of T-2 toxin by a Fusarium resembling Fusarium poae. Mycopathologia. 1999;147:89–96. doi: 10.1023/A:1007060108935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha O., Ansari K., Doohan F.M. Effects of trichothecene mycotoxins on eukaryotic cells: A review. Food Addit. Contam. 2015;22:369–378. doi: 10.1080/02652030500058403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuda D., Ishida M., Yamaguchi K., Yamaguchi I., Kimura M., Nishiuchi T. Phytotoxic effects of trichothecenes on the growth and morphology of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:1617–1626. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desjardins A.E. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics and Biology. APS Press; St. Paul, MN, USA: 2006. pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell K., Kistler H.C., Tacke B.K., Casper H.H. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7905–7910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130193297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward T.J., Bielawski J.P., Kistler H.C., Sullivan E., O’Donnell K. Ancestral polymorphism and adaptive evolution in the trichothecene mycotoxin gene cluster of phytopathogenic Fusarium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9278–9283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142307199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoki T., Ward T.J., Kistler H.C., O’Donnell K. Systematics, phylogeny and trichothecene mycotoxin potential of Fusarium Head Blight cereal pathogens. Mycotoxins. 2012;62:91–102. doi: 10.2520/myco.62.91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell K., Rooney A.P., Proctor R.H., Brown D.W., McCormick S.P., Ward T.J., Frandsen R.J.N., Lysøe E., Rehner S.A., Aoki T., et al. Phylogenetic analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 support a middle Cretaceous origin for a clade comprising all agriculturally and medically important fusaria. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013;52:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marasas W.F.O., Yagen B., Sydenham E.W., Combrinck S., Thiel P.G. Comparative yields of T-2 toxin and related trichothecenes from five toxicologically important strains of Fusarium sporotrichioides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987;53:693–696. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.693-696.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langseth W., Bernhoft A., Rundberget T., Kosiak B., Gareis M. Mycotoxin production and cytotoxicity of Fusarium strains isolated from Norwegian cereals. Mycopathologia. 1999;144:103–113. doi: 10.1023/A:1007016820879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thrane U., Adler A., Clasen P.E., Galvano F., Langseth W., Lew H., Logrieco A., Nielsen K.F., Ritieni A. Diversity in metabolite production by Fusarium langsethiae, Fusarium poae, and Fusarium sporotrichioides. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004;95:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yli-Mattila T., Ward T.J., O’Donnell K., Proctor R.H., Burkin A.A., Kononenko G.P., Gavrilova O.P., Aoki T., McCormick S.P., Gagkaeva T.Y. Fusarium sibiricum sp. nov, a novel type A trichothecene-producing Fusarium from northern Asia closely related to F. sporotrichioides and F. langsethiae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011;147:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beremand M.N., Desjardins A.E. Trichothecene biosynthesis in Gibberella pulicaris: Inheritance of C-8 hydroxylation. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1988;3:167–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01569523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown D.W., Proctor R.H., Dyer R.B., Plattner R.D. Characterization of a Fusarium 2-gene cluster involved in trichothecene C-8 modification. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:7936–7944. doi: 10.1021/jf030607+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meek I.B., Peplow A.W., Ake C., Phillips T.D., Beremand M.N. Tri1 encodes the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase for C-8 hydroxylation during trichothecene biosynthesis in Fusarium sporotrichioides and resides upstream of another new Tri gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:1607–1613. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1607-1613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peplow A.W., Meek I.B., Wiles M.C., Phillips T.D., Beremand M.N. Tri16 is required for esterification of position C-8 during trichothecene mycotoxin production by Fusarium sporotrichioides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:5935–5940. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5935-5940.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L.J., Geiser D.M., Proctor R.H., Rooney A.P., O’Donnell K., Trail F., Gardiner D.M., Manners M., Kazan K. Fusarium pathogenomics. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;67:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proctor R.H., Hohn T.M., McCormick S.P. Reduced virulence of Gibberella zeae caused by disruption of a trichothecene toxin biosynthetic gene. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:593–601. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-8-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bai G.H., Desjardins A.E., Plattner R.D. Deoxynivalenol-nonproducing Fusarium graminearum causes initial infection but does not cause disease spread in wheat spikes. Mycopathologia. 2002;153:91–98. doi: 10.1023/A:1014419323550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woloshuk C.P., Shim W.B. Aflatoxins, fumonisins and trichothecenes: A convergence of knowledge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013;37:94–109. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogenhout S.A., van der Hoorn R.A.L., Terauchi R., Kamoun S. Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:115–122. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idnurm A., Howlett B. Pathogenicity genes of phytopathogenic fungi. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2001;2:241–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-6722.2001.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick S.P., Alexander N.J. Fusarium Tri8 encodes a trichothecene C-3 esterase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:2959–2964. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2959-2964.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Donnell K., Sarver B.A.J., Brandt M., Chang D.C., Noble-Wang J., Park B.J., Sutton D.A., Benjamin L., Lindsley M., Padhye A., et al. Phylogenetic diversity and microsphere array-based genotyping of human pathogenic fusaria, including from the multistate contact lens-associated U.S. keratitis outbreaks of 2005 and 2006. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2235–2248. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00533-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell K., Sutton D.A., Rinaldi M.G., Sarver B.A., Balajee S.A., Schroers H.J., Summerbell R.C., Robert V.A., Crous P.W., Zhang N., et al. Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying fusaria from human and animal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:3708–3718. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00989-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D.G. The CLUSTALX windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucl. Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drummond A.J., Ashton B., Buxton S., Cheung M., Cooper A., Duran C., Field M., Heled J., Kearse M., Markowitz S., et al. Geneious v5.4. 2011. [(accessed on 10 January 2015)]. Available online: http://www.geneious.com/

- 40.National Centre for Biotechnology Information. [(accessed on 10 January 2015)]; Available online: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

- 41.Shimodaira H., Hasegawa M. Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1114–1116. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swofford D.L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA, USA: 2002. pp. 24–206. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posada D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rambaut A. FigTree. 2013. [(accessed on 10 January 2015)]. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- 46.Planet P.J. Tree disagreement: Measuring and testing incongruence in phylogenies. J. Biomed. Inform. 2006;39:86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.