Abstract

The nutritional benefits of pomegranate have attracted great scientific interest. The pomegranate, including the pomegranate peel, has been used worldwide for many years as a fruit with medicinal activity, mostly antioxidant properties. Among chronic diseases, osteoporosis, which is associated with bone remodelling impairment leading to progressive bone loss, could eventually benefit from antioxidant compounds because of the involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of osteopenia. In this study, with in vivo and ex vivo experiments, we investigated whether the consumption of pomegranate peel extract (PGPE) could limit the process of osteopenia. We demonstrated that in ovariectomized (OVX) C57BL/6J mice, PGPE consumption was able to significantly prevent the decrease in bone mineral density (−31.9%; p < 0.001 vs. OVX mice) and bone microarchitecture impairment. Moreover, the exposure of RAW264.7 cells to serum harvested from mice that had been given a PGPE-enriched diet elicited reduced osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption, as shown by the inhibition of the major osteoclast markers. In addition, PGPE appeared to substantially stimulate osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity at day 7, mineralization at day 21 and the transcription level of osteogenic markers. PGPE may be effective in preventing the bone loss associated with ovariectomy in mice, and offers a promising alternative for the nutritional management of this disease.

Keywords: pomegranate peel extract, nutritional prevention, bone health, cell lines, animal model

1. Introduction

Bone is a dynamic organ that is continuously and precisely remodelled by the combined roles of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Imbalance in bone remodelling is usually caused by a deregulated coupling between the main bone cells due to an increase in osteoclast resorption activity over the bone-formation rate by osteoblasts or by low bone turnover where both formation and resorption are reduced. This process leads to a common adult bone disease, i.e., osteoporosis [1], which is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and the structural deterioration of the microarchitecture, leading to bone fragility [2]. Many attempts have been made to develop drugs for the prevention and treatment of this disease. Regarding nutritional prevention, despite the traditional focus on calcium and vitamin D, recent preclinical approaches have identified a multitude of nutrients endowed with bone sparing properties [3]. Indeed, it has been shown that polyphenolic compounds such as flavonoids, more precisely, genistein, daidzein, oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and others, exert an effect on osteoporosis [4,5,6,7,8,9], inhibit osteoclast differentiation [10,11,12] and stimulate osteoblast formation [13,14,15,16] in vitro and in vivo.

Among the main dietary sources of such micronutrients, pomegranate (Punica granatum, Punicaceae) has been used extensively in the folk medicine of many cultures [17]. While the relationship between pomegranate composition and its biological effects is not clearly elucidated, many recent advances have been made in the effort to discover the mechanisms involved and to identify the molecules responsible for these actions [18,19]. Various parts of the fruit have been shown to exert antioxidant [20,21], anti-inflammatory [22,23], anticarcigogenic [24,25,26], antiatherosclerotic [27,28], hypolipidemic [29,30], antidiabetic [31,32], antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal activities [33,34,35], on cell lines, in preclinical models and in few human studies [36]. Indeed, the main properties of the pomegranate actually identified thus far are associated with its antioxidant capacity (three times higher than extracts of red wine and tea), and its composition including anthocyanins and tannins [37,38,39]. Actually, it has been reported that reactive oxygen species and low-grade inflammation, both of which contribute to the aging process [40,41,42,43,44,45], are involved in the aetiology of various degenerative diseases, such as osteoporosis [46,47,48,49,50].

The peel of the pomegranate represents almost 26%–30% of the fruit. This part of the fruit has the highest antioxidant capacity (92% of the total antioxidant activity of the fruit [51]) because of its large content of polyphenols such as punicalagin [52], flavonoids (anthocyanins, catechins and other complex flavonoids) and hydrolysable tannins (punicalin, pedunculagin, punicalagin, gallic and ellagic acid) [53]. Pomegranate peel tannins have been widely recognized and used traditionally for their medicinal properties, and several common ailments such as inflammation, diarrhoea, intestinal worms, cough, and infertility have been treated by exploiting pomegranate peel extract [17,54]. Consequently, the exceptional antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of pomegranate peel (together with a long history of use in folk medicine), associated with the need to develop new and innovative strategies for the management of osteoporosis, led us to investigate its role in the issue of bone health. In this study, using a pomegranate peel extract rich in tannins, we hypothesized that the consumption of pomegranate peel extract as a dietary supplement could exert a beneficial effect on bone biology. Moreover, using an in vitro cell culture model with osteoblasts and osteoclasts, we studied the cellular and molecular mechanisms of action that could be involved, and thanks to a murine model of osteoporosis we attempted to confirm observations at the cellular level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pomegranate Peel Extract

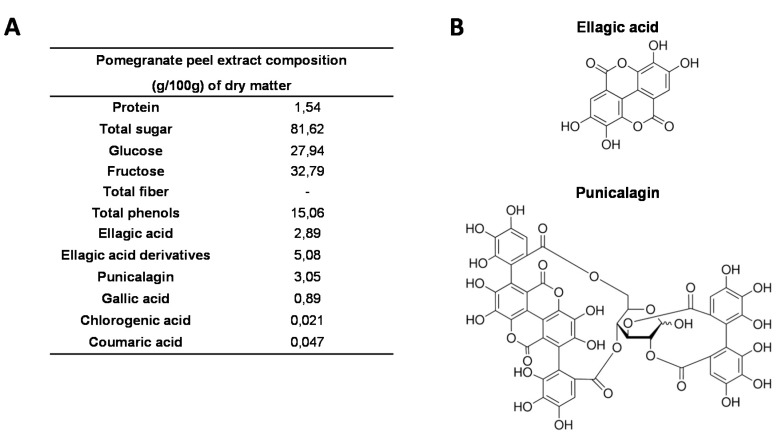

Throughout the study, we used the pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Wonderful cultivar, which is cultured in Israel and was purchased from POMONA (Clermont-Ferrand, France). It has sweet-tart taste, deep purple-red fruits with soft seeds and delicious vinous flavour. For all the in vitro and in vivo studies, we used the same batch of pomegranates that were stored at 4 °C. A careful sampling was performed for the analyses. Fresh fruits were peeled manually, and the peel was squeezed using a commercial turnmix blender (Philips HR2084, France) to obtain a homogenous puree. Pomegranate peel extract (PGPE) was obtained by hydro-alcoholic (ethanol/water* (mass/mass) 70/30 (*water from pomegranate peel)) extraction from peel puree, with a pomegranate/solvent ratio of 1/15 (w/w), at 90 °C, for 3 h. The extract was then filtrated through a 0.2 μm filter, the ethanol was evaporated and the extract was frozen at −20 °C, directly after preparation and until analysis and diet formulation. The administrated dose of 10 mg polyphenols/kg body weight/day on mice corresponds to a consumption of approximately 93 mg polyphenol/day in human (it is estimated that the spontaneous daily intake of polyphenols is approximately 1 g) [55]. Chemical characterization of PGPE composition was performed by AGROBIO (Rennes, France) and VEGEPOLYS INNOVATION (Angers, France) (see PGPE composition on Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Composition of pomegranate peel extract (PGPE). (A) Chemical composition of PGPE (g/100 g dry matter). (B) Chemical structure of ellagic acid and punicalagin, the two major polyphenolic compounds of PGPE.

2.2. Animals Ethics

All animal procedures were approved by the institution’s animal welfare committee (Comité d’Ethique en Matière d’Expérimentation Animale Auvergne: CEMEAA) and were conducted in accordance with the European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (2010-63UE). The animals were housed in the animal facilities of the Human Nutrition Unit at INRA Research Centre [56], Agreement N°: C6334514).

2.3. In Vitro Study Design: Serum Production

Fifty 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from JANVIER (St Berthevin, France). After an acclimatization period of one week, the mice were randomly divided into 2 groups (n = 25 per group) denoted as the PGPE and control (CT) groups. Both groups were fed a control diet (AIN-93G). PGPE (50 mg polyphenol/kg body weight/day ellagic acid equivalent) was given to each animal in the PGPE group by forced oral administration, while the control group received the same amount of physiological saline, using the same procedure. After 10 days, venous blood from all the animals was collected under anaesthesia and centrifuged (3000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature). Serum supernatant was subsequently harvested. Then, serum from the same animal group was pooled, filtered at 45 μm, divided into aliquots and stored at −80 °C until use in the cell culture medium.

2.3.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Murine MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells (ATCC, Washington, DC, USA) were seeded on collagen-1-coated plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2. The cells were maintained in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM; GIBCO, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Paisley, UK) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonza, Levallois-Perret, France) (minimal medium). At 80% confluence, the cells were exposed to different conditions: minimal medium (C−) or minimal medium containing 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (C+; differentiation medium), in the presence of 10% heat-inactivated FBS (FBS) or 7.5% heat-inactivated FBS + 2.5% serum from mice that received physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE), for 21 days.

In addition, RAW264.7, a murine monocytic cell line (ATCC, Washington, DC, USA), was used as an osteoclast model. The cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cell/cm2 and maintained in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM; GIBCO, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Paisley, UK) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (minimal medium). At 80% confluence, the cells were exposed to different conditions: minimal medium (C−) or minimal medium containing 50 ng/mL receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANK-L) (R&D Systems) (C+; differentiation medium), in the presence of 10% heat-inactivated FBS (FBS) or 7.5% heat-inactivated FBS + 2.5% serum from mice that received physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE) for 4 days.

The replacement proportion of FBS by mice serum in these studies was determined by preliminary studies employing RAW264.7 and MC3T3-E1 cells to ensure that no modification of cell differentiation (cell viability, proliferation, specific activity, expression of major makers of cell type) was induced.

Both cell types were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The medium was replaced every 2 days. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times and reproduced 2 times.

2.3.2. Cell Proliferation

RAW264.7 and MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 3.5 × 103 cells per well and then cultured for 48 h or 7 days with 2% serum (2% FBS or 1.25% FBS + 0.75% CT or PGPE mice serum). Cell viability was determined by an XTT-based method using Cell Proliferation Kit II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The OD was determined at 450 nm.

2.3.3. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Measurement

The enzymatic activity of ALP was measured in osteoblasts at days 0, 2, 7 and 14, according to previously published methods [57], adapted to our experimental conditions. Briefly, the osteoblast cultures were rinsed twice with PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, 38297 Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France) prior to freezing at −20 °C. The cells were then lysed by freeze–thaw cycles and homogenized in diethanolamine/magnesium chloride hexahydrate buffer (pH 9.8; Sigma-Aldrich). The cell lysates (10 μL) were added to 200 μL of p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution (6 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Absorbance was assessed at 405 nm, 30 °C, every 150 s for 30 min, using an ELX808 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT, USA). Protein measurement was performed using a BioRad protein assay (BioRad, Munich, Germany). ALP activity was expressed as micromoles of p-nitrophenol per hour per milligram of protein [58].

2.3.4. Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Activity Measurement

TRAP activity was assayed according to the standard method using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate [59]. The medium was removed from osteoclasts cultured in 24-well plates after 3 days, and cell lysates were prepared using NP40 lysis buffer. The samples were incubated in assay buffer (125 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2), 100 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 1 mM L(+) sodium tartrate). The production of p-nitrophenol was determined at 405 nm, 37 °C and expressed as the mean OD per minute per milligram protein.

2.3.5. Mineralization

Osteoblasts seeded in 12-well plates were cultured for 21 days in minimal medium containing 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate to investigate bone nodule formation. Extracellular matrix calcium deposits were stained using Alizarin red dye, as previously described [58]. Osteoblasts were fixed with ice-cold 70% (v/v) ethanol and then stained with Alizarin Red S (40 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min. Mineralization was evaluated by the light microscopy and image processing software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.4. In Vivo Study Design

Thirty 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from JANVIER (St Berthevin, France). After an acclimatization period of one week, the mice were randomly divided into 3 groups (n = 10 per group). Two groups were surgically ovariectomized (OVX), under ketamine/xylazine anaesthesia, while the other animals were sham operated (SH). Paracetamol was added to the water for 24 h post-surgery for pain limitation [60,61].

Control mice (SH Control and OVX Control) were fed a standard AIN-93G diet, while the last group (OVX PGPE) received the standard diet enriched with 2 g/kg of PGPE (i.e., 10 mg polyphenols (ellagic acid equivalents)/kg body weight/day). The diets were purchased from SAFE (Scientific Animal Food and Engineering, Augy, France).

The animals were housed in a controlled environment (12:12 h light-dark cycle, at 20–22 °C, with 50%–60% relative humidity, 1 mouse per plastic cage), with free access to water. Body weight was measured every two days during the study period. Body composition was assessed at the beginning and at the end of the study, using a QMR (Quantitative magnetic resonance) EchoMRI-900™ system (EchoMRI LLC, Houston, TX, USA), without any anaesthesia or sedation. After the 30-day treatment, the mice were sacrificed. The liver, spleen and uterus were weighted. Femurs and tibias were harvested and stored at −80 °C prior to investigation.

2.4.1. Bone Mineral Density (BMD) Analysis

Bone morphological analysis was performed using an eXplore CT 120 scanner (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). After the removal of soft tissues, the left femurs were placed in PBS buffer with 10% formaldehyde at 4 °C for one week and scanned. Acquisition consisted of 360 views acquired in 1 soft tissues, the left femurs were placed in PBS buffer with 1 millisecond exposure/view and X-ray tube settings of 100 kV and 50 mA. CT images were reconstructed using a modified conebeam algorithm with an isotropic voxel of 0.045 x 0.045 x 0.045 mm3. CT scans were analysed using MicroViewH version 2.3 software (General Electric Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). A hydroxyapatite calibration phantom (SB3, Gamex RMI, WI, USA) was used to convert grey-scale levels to hydroxyapatite density values. The trabecular bone of the distal femur was selected for bone mineral density and bone volume fraction (BVF = Bone Volume/Total volume) analyses by fitting a cylindrical region (r = 0.7 mm) of interest in the center of the femur, starting 0.1 mm proximally from the growth plate and extending a further 0.32 mm in the proximal direction. Bone mineral density was estimated as the mean converted grey-scale level within the region of interest.

2.4.2. Bone Micro-Architecture Analysis

To perform a measurement, the specimen was mounted on a turntable that could be shifted automatically in the axial direction (angular step: 0.675 /reconstruction angular range: 186.30). An aluminium filter (0.5 mm thick) was placed between the X-ray source and the sample. The micro-architecture (secondary spongiosa) was analysed using X-ray radiation provided by a micro-CT SkyScan 1072 (BRUKERMICROCT, Kontich, Belgium). Pictures of 1024 × 1024 pixels were obtained using 37 kV and 215 mA. According to the camera settings, the final pixels measured 5.664 mm, leading to a voxel of 1.817 × 1027 mm3. The calculation of histomorphometric parameters was performed using the CTAn H version 1.11 (BRUKER MICROCT, Kontich, Belgium), and NreconH software version 1.6.1.7 [62] (BRUKER MICROCT, Kontich, Belgium).

2.5. Taqman Low Density Arrays (TLDA)

For each experimental group, four sets of extractions were performed with two tibias pooled in each. Frozen bones were ground in liquid nitrogen to obtain a fine powder. Then, total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions from either bone powder for the in vivo experiment or cell culture, using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). RNA was converted to cDNA using the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystems). The resulting cDNA was used for TaqMan® low-density arrays (TLDAs) (Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time PCR system). Relative expression values were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) according to the Data Assist software (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). 18S, GAPDH and actin served as housekeeping genes.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed in the form of mean with standard error (SEM). All the data were analysed using XLSTAT Pro software [63] (Addinsoft, 40 rue Damrémont, Paris, France). In vitro data were analysed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for differences among groups. If the result was found to be significant (p < 0.05), the fisher multiple comparison test was then performed to determine the specific difference between means. TLDA data and in vivo data were analysed using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance, which allows testing for differences among groups. If the result was found to be significant (p < 0.05), the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine the specific difference between means.

3. Results

To determine the accurate potential effect of pomegranate peel extract (PGPE) on bone metabolism, we first developed an in vitro model relevant to nutritional conditions. This model allowed us to consider plasma modifications elicited by PGPE consumption (including both production of metabolites from the pomegranate polyphenols and any systemic effects of those molecules) and to study the impact of pomegranate on bone cell cultures in vitro. For that purpose, serum from mice that had been given PGPE or physiological saline (control) was introduced into the medium of bone cell cultures (in which 25% of FBS was replaced by mouse serum: 7.5% heat-inactivated FBS + 2.5% serum from mice).

3.1. nPGPE Promoted Osteoblast Differentiation

3.1.1. Cell Viability

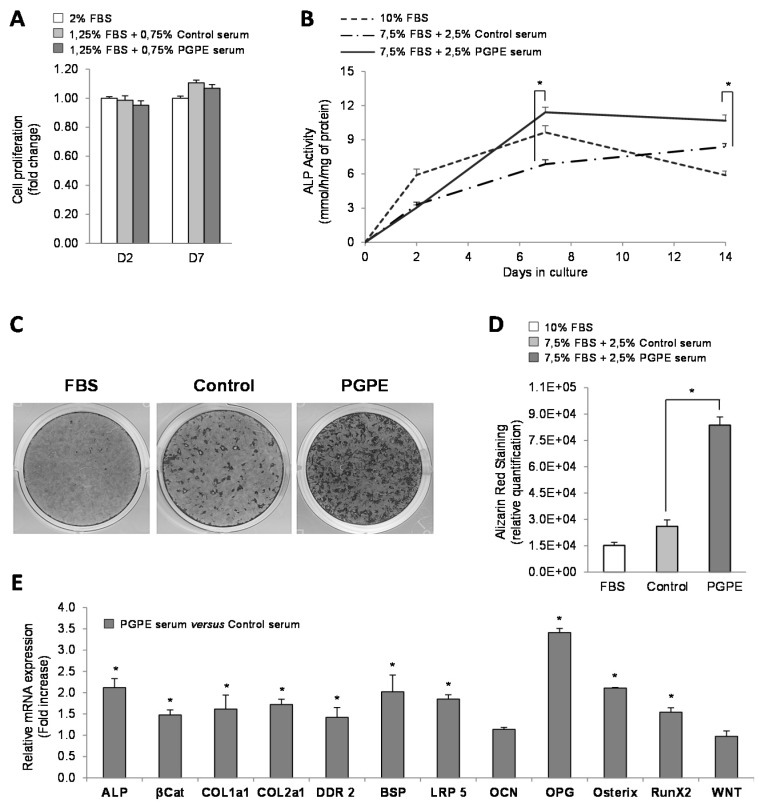

To insure that mouse sera (harvested from mice fed either a standard diet (Control) or the control diet enriched with PGPE) were not deleterious for MC3T3-E1 cells, a cell viability test was performed. Incubation with serum from PGPE animals did not modify the proliferation of the MC3T3-E1 cells, on days 2 and 7, in comparison with cells cultured with serum from CT mice (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Osteoblast viability, differentiation and transcription in culture, after exposure to serum harvested from mice raised either under control conditions or treated with pomegranate peel extract. * p < 0.05 PGPE versus Control condition. (A) Cell proliferation test performed on MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in minimal medium (2% Fetal Bovine Serum, FBS), supplemented with serum from mice given either physiological serum (1.25% FBS + 0.75 Control mice serum) or pomegranate peel extract, PGPE (1.25% FBS + 0.75 PGPE mice serum), after 2 and 7 days of treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 6). (B) Alkaline phosphatase, ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in optimized medium with 10% FBS or with 7.5% FBS + 2.5% serum from mice fed either physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE), after 0, 2, 7 and 14 days of treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). (C,D) Mineralized nodules stained with alizarin red S on Day 21 in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in optimized (C+) medium with 10% FBS or with 7.5% FBS + 2.5% serum from mice exposed to either physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE). (C) Representative image of alizarin red staining for each condition. (D) Relative quantification of alizarin red staining with picture analyser software ImageJ. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, SD (n = 6). (E) Transcriptomic analysis of the main osteoblast markers in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in optimized medium after 7 days of treatment with serum from mice exposed to either physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE). Transcriptomic analysis of MC3T3-E1 mRNA levels determined by Taqman Low-Density Arrays are presented as fold change compared to the Control condition (fold change = 1) as mean ± SD (n = 6). Genes: ALP: alkaline phosphatase; βCat: β-catenin;Coll1a1: collagen 1a1; Coll2a1: collagen 2a1; DDR2: discoidin domain receptor 2; BSP: bone sialoprotein; Lrp5; OCN: osteocalcin; OPG: osteoprotegerin; osteri RunX2 and Wnt.

3.1.2. Effect of PGPE on ALP Activity and Mineralization of MC3T3-E1 Cells

The kinetic measurement of ALP activity in cells treated with mice serum raised in either Control or PGPE conditions on days 2, 7 and 14 was first assessed to investigate the effect of the tested diets on osteoblast differentiation. With regard to the Control condition (FBS), as expected, the osteoblasts treated with optimized medium (C+) exhibited higher ALP activity compared to osteoblasts exposed to a minimal medium (C−), as of day 2 (+72%), day 7 (+374%; p < 0.01) and day 14 (+139%) (data not shown). The cells that had been exposed to PGPE mice serum exhibited higher values compared to the Control condition (+46% at day 7 and +16% at day 14; p < 0.05). (Figure 2B).

In addition to this ALP activity and to target the effect of PGPE on bone mineralization, we analysed calcium deposition by MC3T3-E1 cells under differentiated conditions (C+) and when treated with either PGPE mouse serum or Control mouse serum for 21 days. As shown in Figure 2C, and as expected, the osteoblasts treated with PGPE mouse serum were able to produce many more calcium nodules after 21 days of culture than osteoblasts treated with Control mouse serum (Figure 2D).

3.1.3. Effect of PGPE on transcriptional activity of MC3T3-E1 cells

To better understand the effect of PGPE on osteoblasts, transcriptional analyses of major differentiation and transcription factors were performed. Due to the large number of targets, only the most relevant and significant ones are presented. The expression level of mRNA extracted from MC3T3-E1 cells after 7 days of culture with serum from PGPE mice was compared to the expression level of mRNA from cells treated with serum from Control mice at the same culture time (Fold increase value = 1). As shown in Figure 2E, PGPE led to a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the expression of the major osteogenic markers such as ALP (2.12-fold), collagen 1a1 and 2a1 (Coll1a1 and Coll2a1) (1.62-fold and 1.72-fold respectively), bone sialoprotein (BSP) (2.02-fold), osteocalcin (1.14-fold; not significant) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) (3.41-fold). In addition, discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), a cell surface receptor that plays critical roles in the collagen control of osteoblast differentiation, was up-regulated by PGPE (1.42-fold; p < 0.05). Two members of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway that regulate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation were also up-regulated by PGPE: β-catenin (1.47-fold; p < 0.05) and LRP5 (1.85-fold; p < 0.05), but not Wnt (0.97 fold). Finally, PGPE stimulated the expression of the two master osteoblastic transcription factors: osterix and runX2 (2.11- and 1.54-fold respectively; p < 0.05).

3.2. PGPE Did Not Affect Osteoclast Activity but Impaired Transcription

3.2.1. Cell Viability

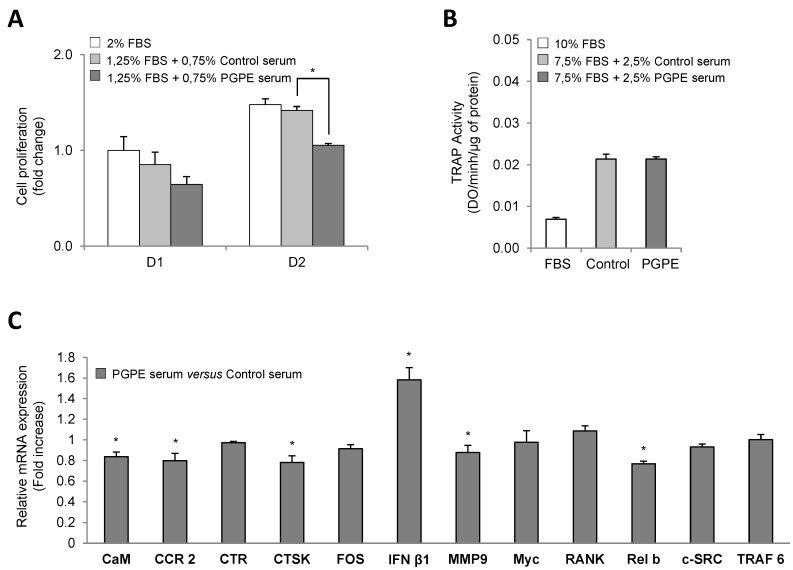

With regard to the osteoclast model (RAW264.7 cells), proliferation was significantly increased at day 2 in all conditions, in comparison to day 1. However, mouse serum induced a slight decrease in osteoclast proliferation on the first culture day compared to what was observed in the FBS condition. No significant difference was noticed between the PGPE and Control serum conditions (−36% and −21% respectively; p < 0.5) (Figure 3A). Then, on day 2, we observed that in the PGPE condition, osteoclast proliferation was reduced compared to the Control mouse serum condition (−26%, p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Osteoclast viability, differentiation and transcription in culture after exposure to serum harvested from mice either raised under control conditions or treated with pomegranate peel extract. * p < 0.05 PGPE versus Control condition. (A) Cell proliferation test performed on RAW264.7 cell line cultured in minimal medium (2% Fetal Bovine Serum, FBS), supplemented with serum from mice exposed to either physiological serum (1.25% FBS + 0.75% Control mice serum) or pomegranate peel extract, PGPE (1.25% FBS + 0.75 PGPE mice serum) after 1 and 2 days of treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 6). (B) Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase, TRAP activity of RAW264.7 cells cultured in optimized medium with 10% FBS or with 7.5% FBS + 2.5% mice serum from animals fed either physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE), after 3 days of treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). (C) Transcriptomic analysis of the main osteoclast markers in RAW264.7 cells cultured in optimized medium after 2 days of treatment with serum from mice exposed to either physiological serum (Control) or pomegranate peel extract (PGPE). Transcriptomic analysis of the Raw264.7 mRNA levels determined by Taqman Low density Arrays are presented as fold change compared to Control condition (fold change = 1) as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). Gene: CaM: calmodulin; CCR2: chemokine receptor 2; CTR: calcitonin receptor; CTSK: cathepsin K; FOS; IFN β1: interferon β1; MMP9: metalloproteinase 9; Myc, RANK: receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB; Relb; c-SRC: and TRAF6.

3.2.2. Effect of PGPE on TRAP Activity of RAW264.7 Cells

We assessed the TRAP activity in RAW264.7 cells after three days of culture to determine whether serum from PGPE mice was able to reduce osteoclast differentiation. As described in Figure 3B, exposure to mouse serum was associated with an increase of such a parameter. However, PGPE did not elicit any change compared to observations using serum from control mice.

3.2.3. Effect of PGPE on Transcriptional Activity of RAW264.7 Cells

To further investigate the effect of PGPE on bone resorption, the expression levels of specific differentiation markers and transcription factors were assessed. A TLDA analysis was therefore performed on mRNA extracted from RAW264.7 cells treated with mouse serum (Control or PGPE) under the differentiated condition (C+) after three days of culture. The expression of the most relevant targets is shown in Figure 3C. The exposure to serum from PGPE mice was compared to the results of Control treated cells (Fold increase value = 1). The TLDA data indicate that the exposure of RAW264.7 differentiated cells to serum from PGPE mice was associated with a slight, but significant (p < 0.05), decrease in the mRNA levels of many crucial osteoclast-specific markers, such as calmodulin (CaM) (0.84-fold), chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) (0.80-fold), cathepsin K (CTSK) (0.78-fold) and metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) (0.88-fold) (Figure 3C). Consistently with this effect, down-regulated expression of a downstream NF-κB subunit, RelB, was observed in the PGPE condition (0.77-fold; p < 0.05). Moreover, the expression of interferon β1 (INFβ1), an osteoclastogenesis inhibitor, was induced (1.58-fold; p < 0.05) in the PGPE condition.

3.3. Confirmation of Cell Culture Results Using a Physiological in Vivo Approach

These ex vivo results were completed by an in vivo investigation of the possible effect of pomegranate using a well-described model of osteoporosis induction by ovariectomy on mice.

3.3.1. Validation of the Animal Model

During this study, the mean body and uterine weights, as well as the lean and fat mass, were measured to ensure that our model conformed to published data. In Table 1, we observed that anthropometric parameters (total weight, fat and lean mass) increased in all the experimental groups throughout the experiment. No significant difference was observed between groups, SH Control vs. OVX Control or OVX PGPE vs. OVX Control. As expected, ovariectomy significantly induced marked uterine atrophy in the OVX Control group (Table 1). This effect on the uterus was not prevented by pomegranate peel extract consumption.

Table 1.

Effect of ovariectomy and pomegranate peel extract consumption for 30 days on physiological parameters in mice.

| Sham | Ovariectomized | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diet | Normal Diet | PGPE Diet | |

| (SH) | (OVX) | (OVX+PGPE) | |

| Initial body weight (g) | 18.9 ± 0.6 | 19.4 ± 0.6 | 19.0 ± 0.5 |

| Initial lean mass (% body weight) | 87.6 ± 3.8 | 87.1 ± 1.2 | 87.1 ± 0.9 |

| Initial fat mass (% body weight) | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 7.9 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 1.2 |

| Final body weight (g) | 19.3 ± 0.8 | 20.3 ± 1.2 | 19.9 ± 0.9 |

| Final lean mass (% body weight) | 88.9 ± 7.3 | 92.3 ± 3.0 | 91.6 ± 2.7 |

| Final fat mass (% body weight) | 9.8 ± 2.2 | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 9.0 ± 2.0 |

| Uterine weight (mg) | 84.4 ± 3.2 | 23.1 ± 2.8 # | 23.7 ± 2.8 |

Mice were sham-operated, SH or ovariectomized, OVX and fed standard diet AIN-93 (Control) or standard diet enriched with 2g/kg of pomegranate peel extract, PGPE representing a dose of 10 mg polyphenols/kg body weight/day (ellagic acid equivalent) for 30 days. Each group contained 10 mice. Values are presented as means ± standard error of the mean, SEM. # p < 0.005 OVX Control versus SH Control group.

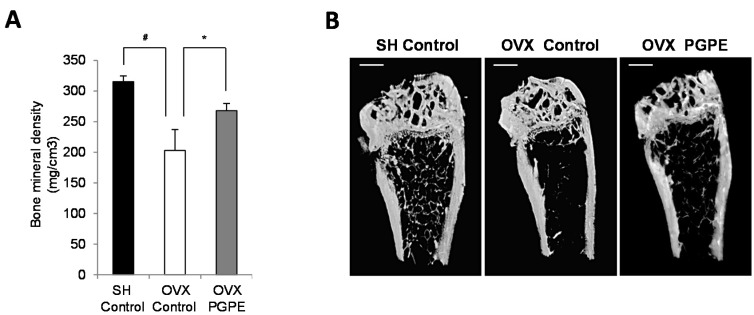

3.3.2. PGPE Consumption Improved Bone Mineral Density in Ovariectomized Mice

Bone morphological parameters using micro-CT analysis were first assessed to evaluate the respective effects of ovariectomy and PGPE consumption on mice. We confirmed the acknowledged effect of oestrogen deficiency on femoral BMD by comparing the OVX Control animals and the SH Control group. Indeed, the OVX Control mice had a significant lower BMD (p < 0.001) than the SH Control mice (−35.6%) (Figure 4A). PGPE consumption was associated with the prevention of such a bone decrease in OVX animals (+31.9%; p < 0.001 compared to the OVX Control animals).

Figure 4.

Effect of ovariectomy and pomegranate peel extract consumption for 30 days on bone parameters in mice. (A) Bone mineral density analysis of left femur by X-ray radiation micro-CT. Mice were sham-operated, SH or ovariectomized, OVX and fed standard diet AIN-93 (Control) or standard diet enriched with 2g/kg of pomegranate peel extract, PGPE representing a dose of 10 mg polyphenols/kg body weight/day (ellagic acid equivalent) for 30 days. Each group contained 10 mice. Results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean, SEM. # p < 0.005 OVX Control versus SH Control group. * p < 0.05 OVX PGPE versus OVX Control. (B) Representative microCT images of the distal left femur for each group: SH Control, OVX Control and OVX PGPE. Scale bars, 1 mm.

3.3.3. PGPE Preserved Bone Microarchitecture in Ovariectomized Mice

We also observed a significant effect on the trabecular bone microarchitecture of the distal femur, as shown in Figure 4B. Again, as expected, bone microarchitecture was significantly impaired by ovariectomy, with an increase in trabecular separation (TbSP +26.1%; p < 0.001) as well as total porosity (Po tot +3.5%; p < 0.01) in comparison with the SH Control group (Table 2). Significant decreases in trabecular number (TbN: −25.0%; p < 0.05), bone per cent volume (BV/TV: −23.6%; p < 0.01), connectivity density (Conn Dn: −19.7%; p < 0.01) and bone surface density (BS/TV: −23.9%; p < 0.05) were also observed. In addition, the consumption of PGPE exhibited a protective effect on bone microarchitecture, as PGPE consumption improved significantly (p < 0.01): BV/TV (+23.1%), TbN (+22.6%), structure model index (SMI: −7.3%), Po tot (−2.52%) and BS/TV (+17.1%) compared to the values measured in the OVX Control animals.

Table 2.

Effect of ovariectomy and pomegranate peel extract consumption for 30 days on bone micro-architectural parameters in mice.

| Sham | Ovariectomized | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diet | Normal Diet | PGPE Diet | |

| (SH) | (OVX) | (OVX+PGPE) | |

| BV/TV (%) | 12.7 ± 0.9 | 9.7 ± 0.6 # | 11.9 ± 0.76 * |

| TbTh (mm) | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| TbN (mm−1) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 # | 1.8 ± 0.07 * |

| TbSP (mm) | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 9.97E-03 # | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| SMI | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.04 * |

| Conn Dn (mm−3) | 278.4 ± 26.5 | 223.5 ± 8.8 | 224.3 ± 12.7 |

| Tb Pf (mm−1) | 25.5 ± 1.1 | 27.7 ± 1.0 | 23.2 ± 1.2 |

| Po tot (%) | 87.3 ± 1.0 | 90.3 ± 0.61 # | 88.1 ± 0.76 * |

| BS/TV (mm−1) | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 0.32 # | 7.9 ± 0.31 * |

Mice were sham-operated, SH or ovariectomized, OVX and fed standard diet AIN-93 (Control) or standard diet enriched with 2g/kg of pomegranate peel extract, PGPE representing a dose of 10 mg polyphenols/kg body weight/day (ellagic acid equivalent) for 30 days. Each group contained 10 mice. Values represent means ± standard error of the mean, SEM. # p < 0.005 OVX Control versus SH Control group. * p < 0.05 OVX PGPE versus OVX Control. Abbreviations: BV/TV: Per cent bone volume; TbTh: trabecular thickness; TbN: trabecular number; TbSP: trabecular spacing; SMI: structure model index; ConnDn: connectivity density; Tb Pf: trabecular pattern factor; Po tot: total porosity; BS/TV: bone surface density.

3.3.4. Pomegranate Intake Was Associated with an Improved Expression Profile of Specific Bone Markers

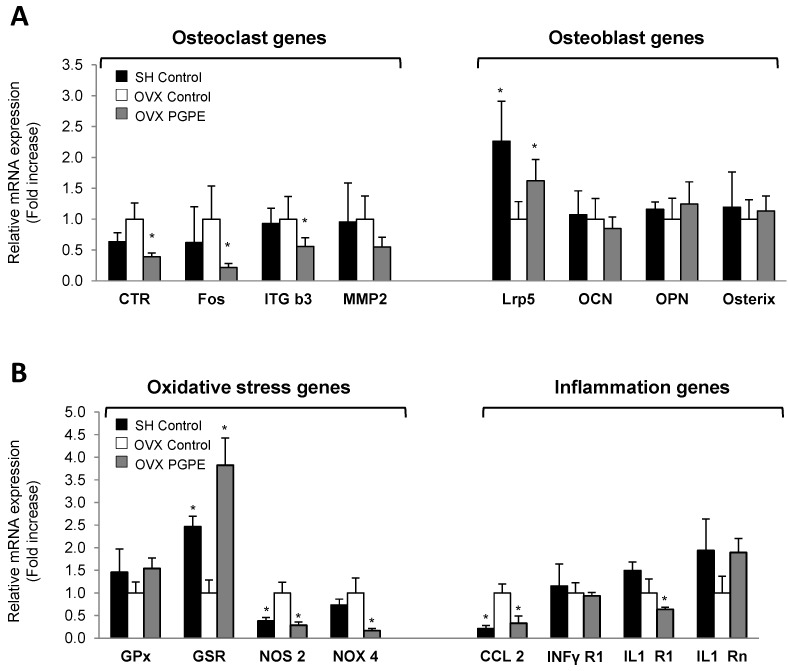

To elucidate the possible molecular mechanisms involved in this effect on bone morphology and to confirm the in vitro findings, we performed a transcriptomic analysis on bone tissue samples using Taqman Low Density Arrays (TLDA, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). Because of the large number of genes modulated, only the most important bone markers are presented. Data on the OVX PGPE group were compared to the data measured for the OVX Control group. The TLDA data on osteoclasts are shown in Figure 5A. Accordingly, PGPE consumption significantly (p < 0.05) down-regulated the mRNA levels of some of the major osteoclast-specific markers: define (0.39 fold) and integrin β3 (ITG b3: 0.56 fold). Fos, a crucial transcription factor for osteoclast differentiation, was also inhibited in the PGPE group (0.22 fold; p < 0.05). Finally, we observed a trend toward down-regulated expression in the OVX PGPE group of a key enzyme for osteoclast activity involved in collagen degradation: the metallo-proteinase 2 (MMP2) (PGt: 0.55; not significant). In addition, regarding the expression of osteoblast-specific markers, the TLDA data presented in Figure 5A show that PGPE consumption by ovariectomized mice was able to significantly improve the expression of a co-receptor implied in Wnt/β-catenin signalling in the osteoblast, LRP5 (1.62 fold; p < 0.05), in comparison with the OVX Control group. However, the other osteoblast markers investigated were not significantly modulated by dietary PGPE.

Figure 5.

Expression profile analysis of bone (A), oxidative stress and inflammation (B) markers in femoral bone from mice fed the control diet (Sham-operated, SH Control. Ovariectomized, OVX Control) or exposed to pomegranate peel extract (OVX PGPE, diet containing 2 g/kg of PGPE), for 30 days. Transcriptomic analysis of bone tissue mRNA levels determined by Taqman Low density Arrays are presented as fold change compared to OVX Control group (fold change = 1). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, SD (n = 8). * p < 0.05. (A) Osteoclast genes: CTR: calcitonin receptor; Fos; ITG b3: integrin β3; MMP2: metalloproteinase 2. Osteoblast genes: Lrp5; OCN: osteocalcin; OPN: osteopontin; RunX2. (B) Oxidative stress genes: GPx: glutathione peroxidase; GSR: glutathione reductase; NOS2: nitric oxide synthase 2; NOX4: NADPH oxidase 4. Inflammation genes: CCL2: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; INFγR1: interferon gamma receptor 1; IL1-R1: interleukin 1 receptor 1; IL1-Rn: interleukin 1 receptor antagonist.

3.3.5. PGPE Enhanced Bone Inflammatory and Oxidative Status Marker Expression in Ovariectomized Mice

To obtain further conclusions regarding the potent bone-sparing effect of pomegranate consumption, we investigated the expression of major inflammation and oxidation markers, which are known to exacerbate bone resorption. We therefore analysed the transcription of some inflammatory and oxidation markers in bone tissue samples using Taqman Low Density Arrays (TLDA, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). Regarding the expression of oxidation markers in the bone microenvironment, dietary PGPE enhanced bone oxidative stress in ovariectomized mice compared to mice given the standard diet, as shown in Figure 5B. PGPE consumption up-regulated the expressions of antioxidant enzymes (GPx (1.54-fold; trend) and GSR (3.82-fold; p < 0.05)), while the expression of the ROS synthesis enzyme NOS2 was down-regulated (0.16-fold; p < 0.001). In addition, PGPE consumption by ovariectomized mice was able to prevent the instigation of a low-grade inflammatory status compared to OVX Control animals, through the down-regulated expression of CCL2 (0.33-fold; p < 0.05) and IL1-R1 (0.64-fold; p < 0.001) and the up-regulated expression of IL1-Rn (1.89-fold; p < 0.001), again supporting our previous results.

4. Discussion

Taken together, these results outline the potential effect of pomegranate peel extract consumption on bone health. Indeed, using an ex vivo investigation that makes it possible to address the overall physiological conditions (by considering the specific metabolism of pomegranate peel extract polyphenols and the possible systemic effects of the consumption of such ingredients) coupled with a well-described preclinical model, we demonstrated that dietary PGPE could improve bone mass and microarchitecture with transcriptional changes in bone tissue during osteoporosis establishment.

Our PGPE is composed of free glucose and fructose (~80%) and polyphenols (~15%) comprising mostly ellagitannins: ellagic acid (~2.9%), derivatives (~5.1%) and punicalagin (~3.1%). In the body, the native ellagitannin forms of PGPE are converted to ellagic acid through a (non-enzymatic) reaction due to acid hydrolysis, which occurs in the caecum at a pH of 8. Punicalagin catabolism leads to the release of ellagic acid, which is largely absorbed and converted by the bacterial microflora in the intestinal lumen to produce the main metabolites of punicalagin, urolithins (mainly forms A and B in humans). While ellagitannins are not found in either the plasma or the urine after the ingestion of pomegranate, their metabolites (ellagic acid and urolithins) are present [23,64,65]. In our studies, the maximal doses of PGPE administered were 10 (in vivo study) or 50 (in vitro study) mg ellagic acid equivalents/kg body weight/day. These doses were safe, as it has been reported that the oral administration of 600 mg/kg/day of pomegranate extract to rats, corresponding to a dose of 180 mg punicalagin/kg/day for 90 days, was devoid of any observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) [66]. Thus, using serum from mice fed with PGPE or physiological serum (Control) on in vitro bone cell culture, we attempted to reproduce the bone nutritive microenvironment induced by PGPE nutritional supplementation in the animals. Indeed, in physiological conditions, bone cells are never in direct contact with the native form of those molecules.

Using our ex vivo MC3T3-E1 cell line model, we found that PGPE significantly stimulated osteoblastogenesis, as demonstrated by increased ALP activity and calcium nodule formation. The transcriptional analysis of major osteoblast lineage markers was consistent with those two markers of osteoblast activity: ALP, BSP, Coll1a1, Coll2a1, DDR2, OCN, OPG were all significantly up-regulated by PGPE. Similarly, an increase in the expression of the two main osteoblastic transcription factors, osterix and runx2, allowed us to hypothesize that transcriptional changes might contribute to the improved osteoblast function [67,68]. Previous works conducted using MC3T3-E1 cells have suggested an osteogenic role of a pomegranate ethanolic extract [20] or pomegranate concentrate powder extract [69] underlined by increased ALP activity, even though the authors did not consider the particular metabolism of pomegranate micronutrients.

We also investigated, for the first time, the effects of PGPE on bone cell resorption based on an in vitro concept using RAW264.7. We found that serum from PGPE mice was able to inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation, as shown by the down-regulation of the expression of specific osteoclast markers (calmodulin, CCR2, calcitonin receptor, cathepsin K, MMP-9) [70]. We observed a consistent decreased expression of relB, the downstream NF-κB subunit responsible for osteoclast differentiation [71]. In addition, the expression of interferon β1, an inhibitor of osteoclastogenesis [72], was up-regulated, thus providing a potential explanation for the PGPE-related inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Consistently with our data, an in vitro anti-resorptive activity of pomegranate pericarp extract has also been suggested, as it was shown to inhibit the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) expression in MG-63 human osteosarcoma cells [73]. To date, except for the work conducted with ellagitannin (furosin, extracted from Euphorbia helioscopia) on osteoclasts [74], showing the suppression of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and function through the inhibition of MAP kinase activation, no data have targeted the role of pomegranate polyphenols on RAW264.7 osteoclasts.

In agreement with those results, in vivo investigation here also demonstrated that PGPE consumption was associated with the decrease of pro-resorption marker expression using Taqman Low density Arrays.

In addition to the direct effects on bone demonstrated by our in vitro data, PGPE could modulate bone physiology through other mechanisms. Native ellagitannin forms of PGPE are hydrolysed by intestinal microflora into punicalagins and ellagic acid, which act as prebiotics. These molecules might contribute to the positive effect on bone [75,76]. They are known to enhance the growth of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli in the intestine, leading to increased production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [77]. SCFAs contribute directly to the enhancement of Ca absorption via a cation exchange mechanism (increased exchange of cellular H+ for luminal Ca2+) [78,79]. The extract of pomegranate pericarp could act as selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs ) on bone as well, as it has an antioestrogenic effect in the mammary gland, without compromising the beneficial effects of oestrogen in the cardiovascular and skeletal system [80]. This SERM-like effect could be attributed to ellagic acid. In vivo, this compound prevents bone loss after tooth extraction in normal [81] or diabetic rats [82] with an increase of ALP expression. In ovariectomized (OVX) rats, an extract of Punica granatum peel has been shown to induce a simultaneous, dose-dependent increase in femoral BMD and uterine weight, suggesting a potent oestrogenic activity of the ellagic acid present in the extract [83]. These effects were equivalent to the effects of Tamoxifen in increasing femoral mineral content and osteoblast number [84]. Moreover, OVX rats fed with dried pomegranate concentrate powder (PCP) extracts containing 0.90 mg/g of ellagic acid show increased serum estradiol and bALP levels with decreased serum osteocalcin compared with OVX control rats [85]. The failure load of the femur was also significantly increased, suggesting that the PCP treatment activates osteoblast differentiation and inhibits bone mineralization and turnover. In vitro, ellagic acid induces nodule mineralization in an osteoblastic cell line (KS483) through a pathway involving the oestrogen receptor [86,87]. However in our in vivo experiment, we did not observe any difference in uterine weight between the OVX control and the OVX PGPE groups. This result could be explained by the lower dose [83].

In addition, looking beyond the traditional bone perspective, because inflammation and oxidative stress play a major role in the modulation of bone remodelling, [47,88], we investigated the expression of major markers of such processes using Taqman Low density Arrays. We showed that PGPE consumption lowers pro-inflammatory markers and enzymes implicated in reactive oxygen species, ROS synthesis expression (Chemokine ligand 2, CCL2; Interleukin 1 receptor 1, IL1-R1; nitric oxide synthase 2, NOS2 and NADPH oxidase 4, NOX4) and enhances the expression of anti-inflammatory markers and the enzymes implicated in the anti-oxidant process (Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, IL1-Rn; glutathione peroxidase, GPx; glutathione reductase, GSR). The flavonoid content and their derivatives (rutin, gallic acid, ellagic acid and punicalagin) of the peel fraction of pomegranate have been frequently utilized as antioxidants in various dietary supplements [76,89]. In vivo, a pomegranate extract diet rich in ellagitannins has been acknowledged to suppress inflammation by decreasing the IL-6 level in the joints of collagen-induced arthritis in mice [90], while the consumption of pomegranate decreases oxidative status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [91]. In vitro, it has been shown that the hydrolysable tannin punicalagin from dried pomegranate peels may have an anti-inflammatory effect on bone metabolism by inhibiting PGE2 production and cyclooxygenase 2, COX-2 expression in lipopolysaccharide, LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells [92] and/or repressing osteoclast differentiation through the downregulation of Nuclear Factor Of Activated T-Cells, NFATc1 expression and decreased phosphorylation of the Akt and JNK pathways [93]. Likewise, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of urolithins have been extensively demonstrated in vitro [94,95].

In summary, our study demonstrates that PGPE metabolites can directly modulate bone cell differentiation, leading to an improved resorption/formation ratio together with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects in the bone microenvironment. This ability can explain the improvement in bone mass and microarchitecture in our model of osteoporosis. These encouraging data suggest that pomegranate consumption could be a promising alternative and complementary therapeutic agent for the prevention of osteoporosis. Nevertheless, more studies are still warranted to further determine the molecular mechanisms involved and to investigate whether these ex vivo and preclinical data can be extrapolated to the human situation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by Greentech and INRA, UMR 1019, UNH, Clermont-Ferrand. The authors are also grateful to the staff from the Animal Facilities (Installation Experimentale de Nutrition, Saint Genès Champanelle, France [56]) who provided everyday care to the mice.

Author Contributions

M.S., L.R., Y.W. and V.C. contributed to the study conception and design. M.S., L.L., M.J.D. and P.L. collected data and performed analysis. P.P. and E.M.N. performed the μCt analysis. M.S., Y.W. and V.C. interpreted the data. M.S., L.L., M.J.D., Y.W. and V.C. drafted the manuscript. All the authors critically revised and approved its final version.

Conflict of Interest

Mélanie Spilmont was a PhD student funded by Greentech. Laurent Rios worked for Greentech during this project and is now a university professor. Laurent Léotoing, Marie-Jeanne Davicco, Patrice Lebecque, Elisabeth Miot-Noirault, Paul Pilet, Yohann Wittrant, and Véronique Coxam declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rachner T.D., Khosla S., Hofbauer L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet. 2011;377:1276–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62349-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandhu S.K., Hampson G. The pathogenesis, diagnosis, investigation and management of osteoporosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011;64:1042–1050. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.077842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulman R.C., Weiss A.J., Mechanick J.I. Nutrition, bone, and aging: An integrative physiology approach. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2011;9:184–195. doi: 10.1007/s11914-011-0079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scalbert A., Manach C., Morand C., Remesy C., Jimenez L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005;45:287–306. doi: 10.1080/1040869059096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonseca D., Ward W.E. Detection of isoflavones in mouse tibia after feeding daidzein. J. Med. Food. 2006;9:436–439. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagiwara K., Goto T., Araki M., Miyazaki H., Hagiwara H. Olive polyphenol hydroxytyrosol prevents bone loss. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;662:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishimi Y., Yoshida M., Wakimoto S., Wu J., Chiba H., Wang X., Takeda K., Miyaura C. Genistein, a soybean isoflavone, affects bone marrow lymphopoiesis and prevents bone loss in castrated male mice. Bone. 2002;31:180–185. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puel C., Mathey J., Agalias A., Kati-Coulibaly S., Mardon J., Obled C., Davicco M.J., Lebecque P., Horcajada M.N., Skaltsounis A.L., et al. Dose-response study of effect of oleuropein, an olive oil polyphenol, in an ovariectomy/inflammation experimental model of bone loss in the rat. Clin. Nutr. 2006;25:859–868. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J., Wang X.X., Chiba H., Higuchi M., Takasaki M., Ohta A., Ishimi Y. Combined intervention of exercise and genistein prevented androgen deficiency-induced bone loss in mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;94:335–342. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00498.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horcajada M.N., Offord E. Naturally plant-derived compounds: Role in bone anabolism. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012;5:205–218. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B., Yu S. Genistein prevents bone resorption diseases by inhibiting bone resorption and stimulating bone formation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:780–786. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rassi C.M., Lieberherr M., Chaumaz G., Pointillart A., Cournot G. Down-regulation of osteoclast differentiation by daidzein via caspase 3. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17:630–638. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trzeciakiewicz A., Habauzit V., Horcajada M.N. When nutrition interacts with osteoblast function: Molecular mechanisms of polyphenols. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2009;22:68–81. doi: 10.1017/S095442240926402X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wilde A., Lieberherr M., Colin C., Pointillart A. A low dose of daidzein acts as an erbeta-selective agonist in trabecular osteoblasts of young female piglets. J. Cell Physiol. 2004;200:253–262. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santiago-Mora R., Casado-Diaz A., de Castro M.D., Quesada-Gomez J.M. Oleuropein enhances osteoblastogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis: The effect on differentiation in stem cells derived from bone marrow. Osteoporos. Int. 2011;22:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto E., Yamaguchi M. Anabolic effect of genistein in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2000;5:515–520. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.5.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lansky E.P., Newman R.A. Punica granatum (pomegranate) and its potential for prevention and treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:177–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viuda-Martos M., Fernández-López J., Pérez-Álvarez J.A. Pomegranate and its many functional components as related to human health: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010;9:635–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahimi H.R., Arastoo M., Ostad S.N. A comprehensive review of punica granatum (pomegranate) properties in toxicological, pharmacological, cellular and molecular biology researches. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2012;11:385–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y.H., Choi E.M. Stimulation of osteoblastic differentiation and inhibition of interleukin-6 and nitric oxide in Mc3t3-E1 cells by pomegranate ethanol extract. Phytother. Res. 2009;23:737–739. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenblat M., Volkova N., Aviram M. Pomegranate juice (PJ) consumption antioxidative properties on mouse macrophages, but not pj beneficial effects on macrophage cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism, are mediated via pj-induced stimulation of macrophage pon2. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollebeeck S., Winand J., Herent M.F., During A., Leclercq J., Larondelle Y., Schneider Y.J. Anti-inflammatory effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) husk ellagitannins in Caco-2 cells, an in vitro model of human intestine. Food Funct. 2012;3:875–885. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10258g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larrosa M., Gonzalez-Sarrias A., Yanez-Gascon M.J., Selma M.V., Azorin-Ortuno M., Toti S., Tomas-Barberan F., Dolara P., Espin J.C. Anti-inflammatory properties of a pomegranate extract and its metabolite urolithin-A in a colitis rat model and the effect of colon inflammation on phenolic metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010;21:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasimsetty S.G., Bialonska D., Reddy M.K., Ma G., Khan S.I., Ferreira D. Colon cancer chemopreventive activities of pomegranate ellagitannins and urolithins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:2180–2187. doi: 10.1021/jf903762h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larrosa M., Tomas-Barberan F.A., Espin J.C. The dietary hydrolysable tannin punicalagin releases ellagic acid that induces apoptosis in human colon adenocarcinoma Caco-2 cells by using the mitochondrial pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006;17:611–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syed D.N., Chamcheu J.C., Mukhtar V.M. Pomegranate extracts and cancer prevention: Molecular and cellular activities. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012;13:1149–1161. doi: 10.2174/1871520611313080003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aviram M., Volkova N., Coleman R., Dreher M., Reddy M.K., Ferreira D., Rosenblat M. Pomegranate phenolics from the peels, arils, and flowers are antiatherogenic: Studies in vivo in atherosclerotic apolipoprotein e-deficient (e 0) mice and in vitro in cultured macrophages and lipoproteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:1148–1157. doi: 10.1021/jf071811q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenblat M., Volkova N., Coleman R., Aviram M. Pomegranate byproduct administration to apolipoprotein e-deficient mice attenuates atherosclerosis development as a result of decreased macrophage oxidative stress and reduced cellular uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:1928–1935. doi: 10.1021/jf0528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuhrman B., Volkova N., Aviram M. Pomegranate juice inhibits oxidized LDL uptake and cholesterol biosynthesis in macrophages. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005;16:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esmaillzadeh A., Tahbaz F., Gaieni I., Alavi-Majd H., Azadbakht L. Concentrated pomegranate juice improves lipid profiles in diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. J. Med. Food. 2004;7:305–308. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Ortiz M., Martinez-Abundis E., Espinel-Bermudez M.C., Perez-Rubio K.G. Effect of pomegranate juice on insulin secretion and sensitivity in patients with obesity. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2011;58:220–223. doi: 10.1159/000330116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagri P., Ali M., Aeri V., Bhowmik M., Sultana S. Antidiabetic effect of punica granatum flowers: Effect on hyperlipidemia, pancreatic cells lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in experimental diabetes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fawole O.A., Makunga N.P., Opara U.L. Antibacterial, antioxidant and tyrosinase-inhibition activities of pomegranate fruit peel methanolic extract. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2012;12:200. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdollahzadeh S., Mashouf R., Mortazavi H., Moghaddam M., Roozbahani N., Vahedi M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of Punica granatum peel extracts against oral pathogens. J. Dent. 2011;8:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haidari M., Ali M., Ward Casscells S., 3rd, Madjid M. Pomegranate (punica granatum) purified polyphenol extract inhibits influenza virus and has a synergistic effect with oseltamivir. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:1127–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johanningsmeier S.D., Harris G.K. Pomegranate as a functional food and nutraceutical source. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;2:181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030810-153709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haber S.L., Joy J.K., Largent R. Antioxidant and antiatherogenic effects of pomegranate. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2011;68:1302–1305. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo C., Yang J., Wei J., Li Y., Xu J., Jiang Y. Antioxidant activities of peel, pulp and seed fractions of common fruits as determined by frap assay. Nutr. Res. 2003;23:1719–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2003.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noda Y., Kaneyuki T., Mori A., Packer L. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: Delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:166–171. doi: 10.1021/jf0108765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause K.H. Aging: A revisited theory based on free radicals generated by NOX family NADPH oxidases. Exp. Gerontol. 2007;42:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probst-Hensch N.M. Chronic age-related diseases share risk factors: Do they share pathophysiological mechanisms and why does that matter? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010 doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Syslova K., Bohmova A., Mikoska M., Kuzma M., Pelclova D., Kacer P. Multimarker screening of oxidative stress in aging. Oxid. Med Cell. Longev. 2014;2014:562–860. doi: 10.1155/2014/562860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balcerczyk A., Gajewska A., Macierzynska-Piotrowska E., Pawelczyk T., Bartosz G., Szemraj J. Enhanced antioxidant capacity and anti-ageing biomarkers after diet micronutrient supplementation. Molecules. 2014;19:14794–14808. doi: 10.3390/molecules190914794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howcroft T.K., Campisi J., Louis G.B., Smith M.T., Wise B., Wyss-Coray T., Augustine A.D., McElhaney J.E., Kohanski R., Sierra F. The role of inflammation in age-related disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:84–93. doi: 10.18632/aging.100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wauquier F., Barquissau V., Leotoing L., Davicco M.J., Lebecque P., Mercier S., Philippe C., Miot-Noirault E., Chardigny J.M., Morio B., et al. Borage and fish oils lifelong supplementation decreases inflammation and improves bone health in a murine model of senile osteoporosis. Bone. 2012;50:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lacativa P.G., Farias M.L. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Arq Bras Endocrinol. Metabol. 2010;54:123–132. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302010000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wauquier F., Leotoing L., Coxam V., Guicheux J., Wittrant Y. Oxidative stress in bone remodelling and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manolagas S.C., Parfitt A.M. What old means to bone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;21:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koh J.M., Lee Y.S., Kim Y.S., Kim D.J., Kim H.H., Park J.Y., Lee K.U., Kim G.S. Homocysteine enhances bone resorption by stimulation of osteoclast formation and activity through increased intracellular ros generation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1003–1011. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozgocmen S., Kaya H., Fadillioglu E., Aydogan R., Yilmaz Z. Role of antioxidant systems, lipid peroxidation, and nitric oxide in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2007;295:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zahin M., Aqil F., Ahmad I. Broad spectrum antimutagenic activity of antioxidant active fraction of Punica granatum L. Peel extracts. Mutat. Res. 2010;703:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzulker R., Glazer I., Bar-Ilan I., Holland D., Aviram M., Amir R. Antioxidant activity, polyphenol content, and related compounds in different fruit juices and homogenates prepared from 29 different pomegranate accessions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:9559–9570. doi: 10.1021/jf071413n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ismail T., Sestili P., Akhtar S. Pomegranate peel and fruit extracts: A review of potential anti-inflammatory and anti-infective effects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mousavinejad G., Emam-Djomeh Z., Rezaei K., Khodaparast M.H.H. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds and their effects on antioxidant activity in pomegranate juices of eight iranian cultivars. Food Chem. 2009;115:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manach C., Scalbert A., Morand C., Remesy C., Jimenez L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Installation expérimentale de nutrition. [(accessed on 26 October 2015)]. Available online: https://www6.clermont.inra.fr/unh/PlateauTechniques/Installation-Experimentale-de-Nutrition.

- 57.Sabokbar A., Millett P.J., Myer B., Rushton N. A rapid, quantitative assay for measuring alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblastic cells in vitro. Bone Miner. 1994;27:57–67. doi: 10.1016/S0169-6009(08)80187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trzeciakiewicz A., Habauzit V., Mercier S., Barron D., Urpi-Sarda M., Manach C., Offord E., Horcajada M.N. Molecular mechanism of hesperetin-7-O-glucuronide, the main circulating metabolite of hesperidin, involved in osteoblast differentiation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:668–675. doi: 10.1021/jf902680n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wittrant Y., Gorin Y., Woodruff K., Horn D., Abboud H.E., Mohan S., Abboud-Werner S.L. High D(+)glucose concentration inhibits rankl-induced osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 2008;42:1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalu D.N. The ovariectomized rat model of postmenopausal bone loss. Bone Miner. 1991;15:175–191. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(91)90124-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lei Z., Xiaoying Z., Xingguo L. Ovariectomy-associated changes in bone mineral density and bone marrow haematopoiesis in rats. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2009;90:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruker. [(accessed on 26 October 2015)]. Available online: http://bruker-microct.com/products/downloads.htm.

- 63.XLSTAT. [(accessed on 26 October 2015)]. Available online: https://www.xlstat.com/fr/

- 64.Espin J.C., Gonzalez-Barrio R., Cerda B., Lopez-Bote C., Rey A.I., Tomas-Barberan F.A. Iberian pig as a model to clarify obscure points in the bioavailability and metabolism of ellagitannins in humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:10476–10485. doi: 10.1021/jf0723864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez-Sarrias A., Gimenez-Bastida J.A., Garcia-Conesa M.T., Gomez-Sanchez M.B., Garcia-Talavera N.V., Gil-Izquierdo A., Sanchez-Alvarez C., Fontana-Compiano L.O., Morga-Egea J.P., Pastor-Quirante F.A., et al. Occurrence of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acid metabolites and proliferation markers expression response in the human prostate gland upon consumption of walnuts and pomegranate juice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010;54:311–322. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel C., Dadhaniya P., Hingorani L., Soni M.G. Safety assessment of pomegranate fruit extract: Acute and subchronic toxicity studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:2728–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang C. Molecular mechanisms of osteoblast-specific transcription factor osterix effect on bone formation. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2012;44:659–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y., Su J., Yu J., Bu X., Ren T., Liu X., Yao L. An essential role of discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2) in osteoblast differentiation and chondrocyte maturation via modulation of Runx2 activation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:604–617. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sreekumar S., Sithul H., Muraleedharan P., Azeez J.M., Sreeharshan S. Pomegranate fruit as a rich source of biologically active compounds. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:686921. doi: 10.1155/2014/686921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boyle W.J., Simonet W.S., Lacey D.L. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vaira S., Johnson T., Hirbe A.C., Alhawagri M., Anwisye I., Sammut B., O'Neal J., Zou W., Weilbaecher K.N., Faccio R., et al. RelB is the NF-kB subunit downstream of nik responsible for osteoclast differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3897–3902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708576105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coelho L.F., Magno de Freitas Almeida G., Mennechet F.J., Blangy A., Uze G. Interferon-alpha and -beta differentially regulate osteoclastogenesis: Role of differential induction of chemokine cxcl11 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11917–11922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502188102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin Y., Murray M.A., Garrett I.R., Gutierrez G.E., Nyman J.S., Mundy G., Fast D., Gellenbeck K.W., Chandra A., Ramakrishnan S. A targeted approach for evaluating preclinical activity of botanical extracts for support of bone health. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014;3:e13. doi: 10.1017/jns.2014.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park E.K., Kim M.S., Lee S.H., Kim K.H., Park J.Y., Kim T.H., Lee I.S., Woo J.T., Jung J.C., Shin H.I., et al. Furosin, an ellagitannin, suppresses rankl-induced osteoclast differentiation and function through inhibition of map kinase activation and actin ring formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;325:1472–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Z., Summanen P.H., Komoriya T., Henning S.M., Lee R.P., Carlson E., Heber D., Finegold S.M. Pomegranate ellagitannins stimulate growth of gut bacteria in vitro: Implications for prebiotic and metabolic effects. Anaerobe. 2015;34:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akhtar S., Ismail T., Fraternale D., Sestili P. Pomegranate peel and peel extracts: Chemistry and food features. Food Chem. 2015;174:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bialonska D., Ramnani P., Kasimsetty S.G., Muntha K.R., Gibson G.R., Ferreira D. The influence of pomegranate by-product and punicalagins on selected groups of human intestinal microbiota. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010;140:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lutz T., Scharrer E. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on calcium absorption by the rat colon. Exp. Physiol. 1991;76:615–618. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberfroid M., Gibson G.R., Hoyles L., McCartney A.L., Rastall R., Rowland I., Wolvers D., Watzl B., Szajewska H., Stahl B., et al. Prebiotic effects: Metabolic and health benefits. Br. J. Nutr. 2010;104:S1–S63. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sreeja S., Santhosh Kumar T.R., Lakshmi B.S. Pomegranate extract demonstrate a selective estrogen receptor modulator profile in human tumor cell lines and in vivo models of estrogen deprivation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23:725–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Al-Obaidi M.M., Al-Bayaty F.H., Al Batran R., Hassandarvish P., Rouhollahi E. Protective effect of ellagic acid on healing alveolar bone after tooth extraction in rat—A histological and immunohistochemical study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014;59:987–999. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Al-Obaidi M.M., Al-Bayaty F.H., Al Batran R., Hussaini J., Khor G.H. Impact of ellagic acid in bone formation after tooth extraction: An experimental study on diabetic rats. Sci. World J. 2014;2014:908098. doi: 10.1155/2014/908098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Satpathy S., Patra A., Purohit A.P. Estrogenic activity of Punica granatum L. Pell estract. Asian Pac. J. Reprod. 2013;2:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S2305-0500(13)60109-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bahtiar A., Arifin S., Razalifha A., Qomariah N., Wuyung P., Arsianti A. Polar fraction of Punica granatum L. Peel extract increased osteoblast number on ovariectomized rat bone. Int. J. Herbal Med. 2014;2:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kang S.J., Choi B.R., Kim S.H., Yi H.Y., Park H.R., Kim D.C., Choi S.H., Han C.H., Park S.J., Song C.H., et al. Dried pomegranate potentiates anti-osteoporotic and anti-obesity activities of red clover dry extracts in ovariectomized rats. Nutrients. 2015;7:2622–2647. doi: 10.3390/nu7042622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Papoutsi Z., Kassi E., Chinou I., Halabalaki M., Skaltsounis L.A., Moutsatsou P. Walnut extract (juglans regia l.) and its component ellagic acid exhibit anti-inflammatory activity in human aorta endothelial cells and osteoblastic activity in the cell line ks483. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;99:715–722. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507837421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Papoutsi Z., Kassi E., Tsiapara A., Fokialakis N., Chrousos G.P., Moutsatsou P. Evaluation of estrogenic/antiestrogenic activity of ellagic acid via the estrogen receptor subtypes eralpha and erbeta. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:7715–7720. doi: 10.1021/jf0510539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mundy G.R. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Nutr. Rev. 2007;65:S147–S151. doi: 10.1301/nr.2007.dec.S147-S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Middha S.K., Usha T., Pande V. HPLC evaluation of phenolic profile, nutritive content, and antioxidant capacity of extracts obtained from punica granatum fruit peel. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013;2013:296236. doi: 10.1155/2013/296236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shukla M., Gupta K., Rasheed Z., Khan K.A., Haqqi T.M. Consumption of hydrolyzable tannins-rich pomegranate extract suppresses inflammation and joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2008;24:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Balbir-Gurman A., Fuhrman B., Braun-Moscovici Y., Markovits D., Aviram M. Consumption of pomegranate decreases serum oxidative stress and reduces disease activity in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot study. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2011;13:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee C.J., Chen L.G., Liang W.L., Wanga C. Anti-inflammatory effects of punica granatum linne in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem. 2010;118:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iwatake M., Okamoto K., Tanaka T., Tsukuba T. Punicalagin attenuates osteoclast differentiation by impairing nfatc1 expression and blocking AKT- and JNK-dependent pathways. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015;407:161–172. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bialonska D., Kasimsetty S.G., Khan S.I., Ferreira D. Urolithins, intestinal microbial metabolites of pomegranate ellagitannins, exhibit potent antioxidant activity in a cell-based assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:10181–10186. doi: 10.1021/jf9025794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gonzalez-Sarrias A., Larrosa M., Tomas-Barberan F.A., Dolara P., Espin J.C. NF-κB-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acid-derived metabolites, in human colonic fibroblasts. Br. J. Nutr. 2010;104:503–512. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]