Abstract

Development of a cost effective quality vaccine is a key issue in rabies control programme in developing countries. With this perspective, in the present study, challenge virus standard (CVS)-11 strain of rabies virus was adapted to grow in BHK-21 cells, characterized, compared with other viruses including global vaccine strains and field isolates from Indian subcontinent and China at molecular level. This cell adapted virus was evaluated for the production of cost effective veterinary vaccine. The maximum virus titre achieved was 107 fluorescent focus unit (FFU)/mL at 10th passage level. There was no nucleotide difference in the nucleoprotein (N) and glycoprotein (G) genes after adaptation in cell line. Phylogenetic analysis showed that adapted virus was grouped with global vaccine strains, closest being with other CVS strains but distinct from the Indian field isolates. Global vaccine strains including cell adapted CVS-11 virus have 83–87 % identity at nucleotide level of G gene with Indian field viruses. Growth kinetics of cell culture adapted virus showed that the optimum virus titer (around 107 FFU/mL) could be obtained at around 48 h post infection by co-cultivation method using 0.1 multiplicity of infection inoculums at 37 °C. These findings can be used for up scaling of vaccine production. The protective efficacy of test vaccine produced using 106.95 FFU/mL cell culture harvest showed 1.17 IU/mL relative potency by NIH test. Further, adapted virus was found to be suitable for use in rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test.

Keywords: Rabies virus, CVS, BHK-21, Adaptation, Vaccine, NIH test

Introduction

Rabies is an important disease of developing countries. Globally it causes about 8.6 billion USD economic loss annually and the largest component of this loss is shared by developing countries [7]. India alone accounts for over 35 % of the global rabies burden (approximately 20,800 deaths every year). Economic loss due to rabies can be minimized by effective control of canine rabies and by production of cost effective rabies vaccine for veterinary use. Availability of cost effective quality cell culture based rabies vaccine to end user in developing countries may contribute in reduction of high prevalence rate of this disease.

New possibilities became available after successful adaptation of rabies virus in cell culture. Reports of successful replication of various fixed and street strains in variety of cells have become more popular nowadays [5, 16]. However, this adaptation has not helped much in manufacturing of effective vaccines and diagnostics. It is still considered as knowledge governing and technology demanding method due to high expertise, bio-safety and specialized infrastructure requirements. During the past two decades, there have been numerous attempts to develop alternatives like vector vaccine, recombinant vaccine based on G protein expression in a range of systems which led to a number of alternative approaches with the potential for new vaccines against rabies. However, because of the production cost and efficacy issues, tissue culture vaccines are still ranked as the most commonly used and recommended rabies vaccines.

High cost of cell culture rabies vaccine may be one of the factors which limit its use in developing countries. To lower the cost of tissue culture vaccines, several studies were under taken to modify the traditional five-dose regimen and evaluation of intra-dermal route of vaccination [4, 27]. Optimizing virus yield and application of alternative approaches for in–process quality control of vaccine are alternative strategies for the development of a low cost rabies cell-culture vaccine [12, 25]. Such strategy improves the productivity of the upstream process and therefore increases the number of vaccine doses produced per run. Even though, BHK-21 adapted viruses from CVS-11 strain, is being used as vaccine candidate by some of the industries like Indian Immunologicals Limited in India. Availability of the virus along with full characteristics in a public good laboratory like ours will speed up the research and development activities and will open doors for vaccine up-scaling in government laboratories such as State Veterinary Biological Units in India.

Human and veterinary vaccines have difference only in terms of purity and potency. However, in both the cases vaccine should protect host against field rabies virus. An ideal vaccine strain candidate must have been characterized at full length genome or for G and N genes [35]. Genetic difference between field strain and vaccine strain may be one of the reasons for rabies vaccine failure under field conditions. Therefore, any difference in G gene between vaccine strain and field viruses should be critically studied and analysed. It may give an idea that how effective is a vaccine against the field viruses in animal and human beings [16, 18].

Various vaccine strains globally have been approved and recommended by international organizations for rabies vaccine production. Challenge virus standard (CVS-11) strain of rabies is one of such strains approved for vaccine production, recommended for use in RFFIT and internationally used as a challenge virus. It is well characterized strain, developed from the original Pasteur rabies virus (isolated in 1882) by adaptation in mice. The present study was aimed to adapt mice origin CVS-11 strain of rabies virus in BHK-21 cell line and to study the kinetics of the replication in the course of its adaptation, and determination of the optimal harvesting time for subsequent vaccine preparation. The study also aimed to characterize the adapted virus at molecular and immunogenic level. The study may help in evaluating the adapted virus as vaccine candidate for cost effective animal rabies vaccine production and for use in RFFIT, an alternative to mouse neutralization test (MNT). Such efforts are important for resource poor laboratories and countries, for quality vaccine production.

Materials and methods

Cell line and virus

Baby Hamster Kidney cell line (BHK-21 clone13), and mice passaged CVS-11 strain of rabies virus (passage-2) used in the present study were maintained at Division of Biological Products, Indian Veterinary Research Institute. BHK-21 cells were grown in Glasgow’s Minimum Essential Medium (GMEM; Invitrogen, UK) supplemented with fetal calf serum (FCS; 2–10 %; Gibco, Invitrogen, UK).

Laboratory animals

Swiss albino mice of either sex, weighing 12–16 g were procured from Laboratory Animal Resources (LAR) Section, Izatnagar, IVRI and used in the current study. Protocols of the animal experimentation were approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) with approval no. F.1-53/2012-13/JD(R) dated 16 August 2014.

Primers and FITC conjugate

Details of primer pairs used in conventional and real time PCR are as per the details published before [6, 29]. FITC anti-rabies monoclonal globulin conjugate (Catal # REF 800-092, FDI, Fujirebio Diagnostic, Inc, USA) was used in fluorescent antibody test (FAT) and rapid fluorescent foci inhibition test (RFFIT).

Adaptation of CVS-11 strain of rabies virus in BHK-21 cell line

CVS-11 strain of rabies virus infected mice brain suspension (10 % in CVS diluent) was used for infection of BHK-21 cell line by co-cultivation method. After about 24 h post infection (hpi) growth medium (GMEM supplemented with 10 % FCS, pH 7.2) was replaced by maintenance medium (GMEM supplemented with 2 % FCS, pH 7.8 ± 0.2) and the virus was harvested at about 48 hpi. Harvested material was thawed and used as inoculum for next passage. Aforementioned procedure was repeated for every passage until adaptation i.e. optimum virus titre (>106 FFU/mL in this study). At each passage, cultured virus were harvested, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. Virus was detected between passages by techniques viz. FAT, MIT, PCR and real time PCR [12, 25, 29].

Identity confirmation by VNT and mice pathogenicity test

In order to confirm the identity of cell adapted virus, fixed quantity (100 FFU) of cell adapted virus was mixed with serially diluted known anti-rabies antibodies (Vinrig, Hyderabad) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Virus-antibody mixture was used to infect BHK-21 cells and subsequently detected by FAT at 48 hpi. Pathogenicity of cell line adapted virus (10th passage) and parental virus (before adaptation) were studied in mice by intra-cranial inoculation and compared. Each virus sample (40 MICLD50/mice) was inoculated in a group of mice (n = 6) through intra-cranial route, whereas control mice were injected with PBS. All test and control groups of mice were observed for 14 days. From the dead mice, few brain samples were randomly collected and presence of virus was confirmed using FAT.

Molecular characterization

Nucleoprotein and glycoprotein genes from cell adapted virus (10th passage) were amplified using KOD DNA polymerase and sequenced commercially (GCC Biotech, India). Obtained sequences were assembled and analyzed using sequencher version 5.2.4 and MegAlign of Lasergene package (DNASTAR, USA). Sequences of various vaccine strains and field isolates were downloaded from GenBank (NCBI) and used for phylogenetic analysis by MEGA 6.0 software with 1000 bootstrap replicates [32].

Growth kinetics study

Growth pattern of cell adapted virus was studied in BHK-21 cells using 1, 0.1 and 0.01 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of virus. Virus was harvested at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpi followed by titration using FAT.

Rapid fluorescent foci inhibition test (RFFIT)

To assess the suitability of cell adapted CVS virus for use in RFFIT, tenfold serial dilutions of known anti-rabies serum (Vinrig, Hyderabad) was prepared. Virus neutralization test with the uniform quantity of virus (100 FFU/well of Terasaki micro titration plate) at 37 °C for 1 h was performed. Virus antibody mixture was subsequently propagated in BHK-21 cells and growth of virus was detected using FAT.

Preparation and potency estimation of test vaccine

Cell culture harvest showing optimum virus titer was produced in bulk using virus from 10th passage. Inactivated vaccine was prepared using β-propiolactone (1:4000) and inactivation of virus was confirmed by FAT and MIT [10, 12]. Vaccine potency was determined by using standard NIH test [17] wherein four five-fold dilutions of test vaccine (undiluted, 1:5, 1:25, and 1:125) and international reference vaccine standard (1:10, 1:50, 1:250 and 1:1250) were prepared. Groups of 16 Swiss albino mice of 13–16 g weight were given two 0.5 mL doses of different vaccine dilutions by intra-peritoneal route of inoculation on days 0 and 7. After 14th day of the first vaccine inoculation, all mice were challenged with mice origin CVS-11 strain (0.03 ml, containing 45 mice LD50) and observed for 14 days. The median effective dose (ED50) value for test and reference vaccine were calculated and used to determine the relative potency of test vaccine and expressed in International Units.

Results

Adaptation of virus in BHK-21 cell line, its confirmation and quantification

Adaptation of CVS-11 strain of rabies virus in BHK-21 cell line was confirmed by fluorescent antibody test (FAT) after three blind passages. The same sample (3rd passage) was further confirmed by MIT, PCR and real time PCR. Identity of adapted virus was confirmed by VNT and it showed that the adapted virus is efficiently neutralized with known anti-rabies antibodies. In order to stabilize and to increase the virus titre, adapted virus was further passaged up to ten passages and intermittently confirmed by various tests (Table 1). Virus harvest generated at different passage levels were quantified using FAT. The virus titer was found to be increased gradually with serial passages and attained maximum of 107 FFU/mL titre by 10th passage. Similar trends were also observed on assessing virus quantity using qRT-PCR (unpublished data).

Table 1.

The passage wise results of various diagnostic tests used to detect cell adapted CVS-11 virus

| Passage number | Confirmation of virus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAT | MIT | PCR | VNT | Real time PCR | |

| Passage-1 | Blind passages | ||||

| Passage-2 | |||||

| Passage-3 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Passage-4 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Passage-5 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Passage-6 | + | − | + | − | − |

| Passage-7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Passage-8 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Passage-9 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Passage-10 | + | + | + | + | + |

+, showed specific result; −, not done

In-vivo pathogenicity test of BHK-21 adapted virus

Cell adapted virus inoculated intra-cranially in Swiss albino mice (weighing 13–15 g) showed signs specific to rabies after 5 days of inoculation and all the mice died at day 8 post inoculation. As for the mice origin CVS-11 strain, signs were observed at day 6 post inoculation, and all the mice died on day 9 post inoculation. These observations revealed that cell adapted virus is equally pathogenic to mice when inoculated intra-cranially as compared to parental virus.

Molecular characterization of virus

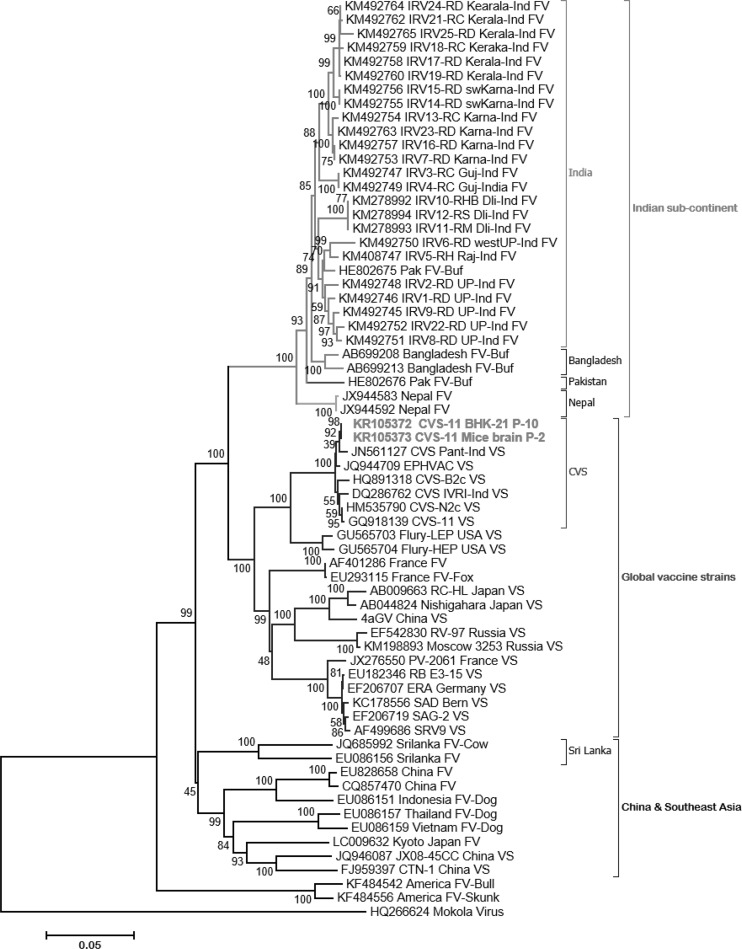

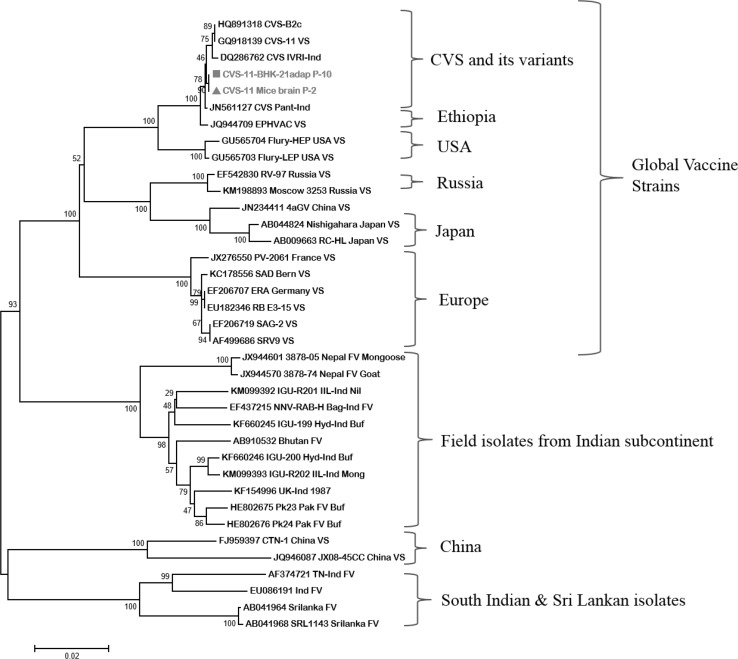

By sequencing, full length of G and N protein genes i.e. 1585 and 1353 nts, respectively were obtained (KR105372-KR105375). Multiple sequence alignment analysis of nucleotide sequences of N and G genes of cell adapted virus showed 100 % identity with original virus. G gene based phylogenetic analysis revealed that the adapted virus was grouped with other CVS and its variants which showed more than 99 % identity. Cell culture adapted virus formed a group along with global vaccine strains yet distinct from the Indian field isolates (Fig. 1) and showed about 83–87 % identity. N gene based phylogenetic analysis revealed the similar findings except for few isolates from Tamil Nadu (southern part of India) which were clustered with various Sri Lankan isolates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on full length G gene nucleotide sequence of reference vaccine strains and recent Indian isolates of rabies virus. Phylogenetic analysis of G gene nucleotide sequence of mice origin (Accession No. KR105373) and BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 strain (Accession No. KR105372) of rabies, rabies vaccine strains used worldwide and recent Indian field isolates were used. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbour-joining program of MEGA version-6. The numbers below the branches are bootstrap values for 1000 replicates. Note that most of the global vaccine strains clustered together, whereas Indian field isolates form a separate group

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on full length N gene nucleotide sequence of reference vaccine strains and various Indian isolates of rabies virus. Phylogenetic analysis of N gene nucleotide sequence of mice origin (Accession No. KR105375) and BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 strain (Accession No. KR105374) of rabies virus along with other vaccine strains and Indian field isolates available in GenBank were used. The tree was constructed using neighbour-joining program of MEGA version-6. The numbers below the branches are bootstrap values for 1000 replicates. Note that both sequences together clustered close to the other sequences of same strain, and also close to other vaccine strains. Whereas these stand entirely different and away from the Indian isolates

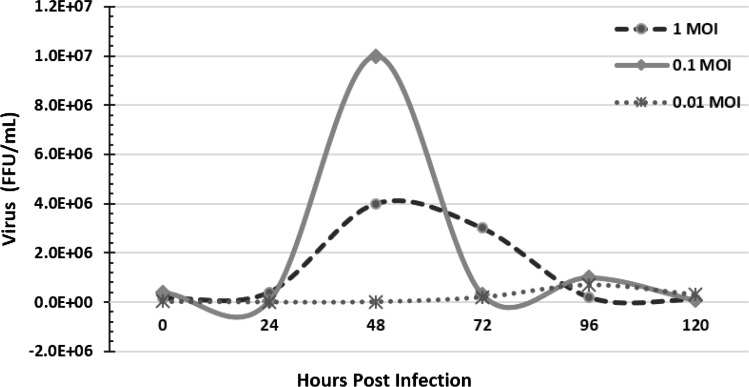

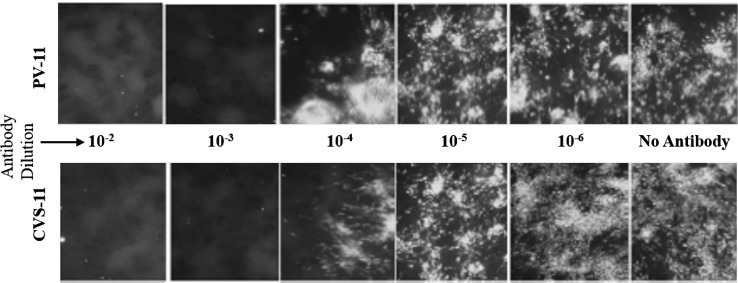

Growth kinetics of virus, its utility in RFFIT and as vaccine candidate

Growth kinetics study indicated that the newly adapted virus yielded optimum virus titre at around 48 hpi, when inoculated with 0.1 MOI (Fig. 3). Use of newly adapted CVS-11 virus in RFFIT showed identical results when compared with PV-11 virus (Fig. 4). A gradual increase in fluorescence (bright intra-cytoplasmic fluorescence) with the decrease in concentration of antibody was observed, which shows the suitability of cell adapted CVS-11 virus for use in RFFIT. Inoculation of mice using cell culture adapted virus (passage-10) proved its pathogenicity, similar to mice origin CVS-11 virus. The results of the NIH test illustrated that the test vaccines prepared using the BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 strain (passage 10) harvest of 106.95 FFU/mL titre without any concentration have a potency equivalent to 1.17 IU/mL, which is more than the OIE recommended standard of 1.0 IU/mL for veterinary rabies vaccine.

Fig. 3.

Growth kinetics of BHK-21 adapted virus using different MOI. Growth kinetics of BHK-21 cell adapted CVS-11 rabies virus using 1, 0.1 and 0.01 MOI of virus by co-cultivation technique. Note that 0.1 MOI of virus is most suitable for optimum virus titre (about 107), at around 48 h post infection

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 strain of rabies for rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT). BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 and PV-11 strain of rabies virus (100 FFU/mL) were incubated with variable dilution (tenfold) of anti-rabies antibody. Virus neutralization was assessed by FAT, after propagation of un-neutralized virus in BHK-21 cells. Note that, wells with higher dilution of antibody show poor or no neutralization and therefore positive by FAT; whereas, lower dilution of antibody show complete neutralization and therefore negative by FAT (Photographs were taken at × 200)

Discussion

Even though the present study was initiated with two cell lines viz vero cells and BHK-21 cells. BHK-21 cells were selected due to quick and early adaptation of the virus and ease of up-scaling through fermenter technology. We successfully adapted CVS-11 strain of rabies virus in BHK-21 cell line through serial passages. The increase in the virus titer indicated that the CVS-11 strain was adapted to BHK-21 cell line. Maximum virus titre obtained was 107 FFU/mL. According to WHO recommendations, virus strains having titre greater than or equal to 106 TCID50/mL and fixed in its growth pattern can be used as vaccine strain [16, 34]. Newly adapted virus was found to be fit on all such parameters. Data on infectivity titre of cell line adapted virus is considered to be sufficient enough for antigen/vaccine production without concentration [25]. During virus adaptation process, it was noticed that the cell adapted virus did not show any distinct cytopathic changes except slow cell growth with more cytoplasmic granulations as observed by other workers using different viral strains and cell lines [2, 23, 25]. This may be because of the nature of rabies virus to cause persistent infection without much cellular lysis [36].

No difference at nucleotide level of N and G genes of cell line adapted CVS-11 strain, implies the genomic stability of cell culture adapted virus even after ten passages in BHK-21 cell line. The findings indicate that it may be equally efficient to induce virus neutralizing antibodies and the principles of quasispecies of RNA viruses could not be defined in this case. Based on the observations, no changes at molecular level and retention of pathogenicity for mice, we may presume that neurotropic variant might be the dominant type present in both mice brain and cell line derived viruses. None of the virulence-associated amino acid residues mutated during the adaptation which shows that the adapted virus is equally sensitive to mice and also to BHK-21 cell line. Therefore, use of cell adapted CVS-11 virus for RFFIT could be most ideal translation of the same virus in mouse neutralization test. Further, it may be possible to use cell culture derived virus for standard challenge study using NIH test with a known infectivity titer.

Glycoprotein gene based phylogenetic analysis revealed that the cell culture adapted virus grouped with global vaccine strains said to be originated from different countries except few Chinese strains (CTN-1 and JX08-45CC). This indicates that the changes in G gene during in vitro passages for fixation of virus are relatively identical in nature and therefore results in close grouping of vaccine viruses. It is also possible that some global vaccine strains said to be originated from different geographical locations might have common original source. WHO laboratories have been source of rabies virus to different laboratories for research and development; due to poor record keeping system and an adoption of different host and methods might be the possible reason for different names given by these laboratories for same virus over a period of time. Further, phylogenetic analysis of various global vaccine strains based on G gene showed about 85–87 % identity with the Indian field isolates. This could be possible because majority of global vaccine strains have originated from the original Pasteur virus (isolated in the year 1882). But, viruses of arctic like lineage which are supposed to be originated somewhere around 1951 are presently circulating in major part of the Indian subcontinent [15, 20, 26]. Within Indian field isolates, geographic location wise sub-grouping was prominently observed for viruses from northern (Uttar Pradesh, Delhi), western (Gujarat), and southern (Karnataka, Kerala) part of the country, which formed a distinct sub-groups. Under Indian scenario, it is clear that the spatial spread of rabies viruses is limited by geographical boundaries or topographical barriers and not by political boundaries. Similar findings on grouping of viruses based on geography was previously reported for isolates from Indian sub-continent [20–22, 28] and also other part of the world [11, 13, 19]. This finding indicates that rough idea for place of origin of rabies virus can be made using G gene based sequence analysis.

In order to be acceptable, rabies vaccine strain candidate virus must be characterized at genetic level and should be capable to elicit more than minimum prescribed potency by NIH test. WHO recommends genetic characterization of vaccine strain at complete genome level or more particularly for G and N genes [35]. The G protein has role in cell attachment, induction of neutralizing antibodies and cell mediated immune response [31]. Therefore, any difference in this gene between vaccine strain and wild viruses should be critically studied and analysed. Further, this may also give an idea that how effective is the vaccine against the field viruses [16, 18]. In the present study we observed identity below 90 % between various global vaccine strains used in India and Indian field viruses. Thus, there is a need to have local isolates having more identity for vaccine preparation. It is reported that the rabies vaccine failure may occur due to genetic difference between local virus isolates and vaccine strains in use and it could be overcome by developing vaccine strains from locally circulating viruses [1, 16]. Therefore, the best vaccine strain is one that is as closely related as possible to the street viruses circulating within the specific geographical location [3, 16, 19].

Nucleoprotein gene based phylogenetic analysis revealed the similar findings as for G gene. It shows close grouping of few isolates from Tamil Nadu (southern part of India) with Sri Lankan isolates. This observation suggests that there might be two distinct rabies virus lineages circulating in India, one in south India (especially Tamil Nadu) and another in rest of the Indian states including neighbouring countries for which the borders are porous [30] in nature as rabies is a trans-boundary animal disease. South Indian viruses might be originated from the Sri Lankan viruses or vice versa over the time because of close geographical location.

Findings of growth pattern of cell adapted virus indicated that the cell culture adapted virus yielded optimum virus titer at around 48 h post infection, when inoculated with 0.1 MOI. This finding is in agreement on growth kinetics of Pasteur virus (PV-11) using similar growth parameters [25]. Findings were also in agreement with OIE recommendation for production of CVS virus [24]. Time for optimum harvest was reported to vary from 2 to 7 days depending on strain of virus, level of adaptation, temperature of propagation (33–37 °C) and MOI [5, 16]. It was observed in our study that the time of optimum harvest gets delayed (48–96 h) with the reduction in initial inoculum (0.1–0.01 MOI). Similar observations were also reported by Hurisa et al., [8] for Evelyn Rokitniki Abelseth (ERA) of rabies virus strain using vero cell line. In line with earlier findings we also observed an eclipse phase of virus which was less than 24 h, and the virus yield was found highest at around 48 h post infection. Several workers also observed an eclipse period of 6–12 h in BHK-21 cells and production of virus for several days without appreciable inhibition of cellular synthesis or appreciable cellular changes in the form of cytopathic effects [9, 14, 33]. Relatively a flat growth curve was observed at 1.0 MOI in the present study. This could be possible because almost all the cells are infected simultaneously after infection. This may affect the growth rate of the cells during co-cultivation method and may have only one virus replication cycle thereby causing low virus titre throughout the investigation period [25]. Also, there might be two or more virus replication cycles possible when infected with low MOI (0.01–0.1).

The findings of RFFIT indicated that the virus can be used for standard potency assay as an alternate tool to VNT. This may help in reducing the use of large number of mice for antibody detection from serum. RFFIT using CVS-11 virus may also have more acceptance internationally, as mouse adapted CVS-11 strain is considered as the most important international challenge virus used globally [35]. Further, the cell adapted virus is identical to mice brain derived virus based on G and N gene sequence. Thus, we may replace the currently in-use virus (PV-11) with the cell line adapted CVS-11 virus without compromising the sensitivity, specificity and reproducibility.

The potency of inactivated test vaccine produced using 106.95 FFU/mL harvest without concentration was determined as 1.17 IU/mL using NIH test, which is above the OIE recommendation (1.0 IU/dose) for veterinary vaccine. This indicates that the cell adapted virus can be used for production of inactivated rabies vaccine without concentrating the crude harvest, which may help to produce cost effective vaccine for veterinary use.

Results of the present study indicated clearly that the BHK-21 adapted CVS-11 strain could induce a strong protective immune response in animals and has potential for use as a virus seed for inactivated vaccine production for veterinary use. However, based on phylogenetic analysis of local field isolates from India and global vaccine strains, it seems that the vaccines developed from well characterized local isolates might be the better choice for vaccine production in India.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to Dr V. K. Chaturvedi and Dr A. K. Tiwari and Director, IVRI for providing the necessary facilities. This work was in part funded by ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute under the Project Code IXX08803.

References

- 1.Aga AM, Mekonnen Y, Hurisa B, Tesfaye T, Lemma H, Kebede G, Niguse D, Gwold G, Urga K. In vivo and in vitro cross neutralization studies of local rabies virus isolates with ERA based cell culture anti-rabies vaccine produced in Ethiopia. J Vaccines Vaccin. 2014;5:256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chavez JH, Yokosawa L, Oliveira TFM, Simoes CMO, Zanetti CR. No association between viral cytopathic effect in McCoy cells and MTT colorimetric assay for the in vitro anti-rabies evaluation. Virus Rev Res. 2013;1:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faber M, Pulmanausahakul R, Nagao K, Prosniak M, Rice AB, Koprowski H, Schnell MJ, Dietzschold B. Identification of viral genomic elements responsible for rabies virus neuroinvasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16328–16332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407289101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goswami A, Plun-Favreau J, Nicoloyannis N, Sampath G, Siddiqui MN, Zinsou JA. The real cost of rabies postexposure treatments. Vaccine. 2005;23:2970–2976. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo C, Wang C, Luo S, Zhu S, Li H, Liu Y, Zhou L, Zhang P, Zhang X, Ding Y, Huang W, Wu K, Zhang Y, Rong W, Tian H. The adaptation of a CTN-1 rabies virus strain to high-titered growth in chick embryo cells for vaccine development. Virol J. 2014;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta PK, Rai A, Rai N, Saini M. Immunogenicity of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding glycoprotein gene of rabies virus CVS in mice and dogs. J Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;7:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, Barrat J, Blanton JD, Briggs DJ, Cleaveland S, Costa P, Freuling CM, Hiby E, Knopf L, Leanes F, Meslin FX, Metlin A, Miranda ME, Muller T, Nel LH, Recuenco S, Rupprecht CE, Schumacher C, Taylor L, Vigilato MAN, Zinsstag J, Dushoff J. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurisa B, Mengeshaa A, Newayesilassiea B, Kergaa S, Kebedea G, Bankoviskyb D, Metlinc A, Urgaa K. Production of cell culture based anti-rabies vaccine in Ethiopia. Procedia Vaccinol. 2013;7:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.provac.2013.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki Y, Wiktor TJ, Koprowski H. Early events of rabies virus replication in tissue cultures. An electron microscopic study. Lab Invest. 1973;28:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagannatha S, Gandhi PR, Vijayakumar R. Kinetics analysis of beta-propiolactone with tangential flow filtration (TFF) concentrated vero cell derived rabies viral protein. J Biol Sci. 2013;13:521–527. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2013.521.527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao W, Yin X, Li Z, Lan X, Li X, Tian X, Li B, Yang B, Zhang Y, Liu J. Molecular characterization of China rabies virus vaccine strain. Virol J. 2011;8:2–11. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar M, Singh RP, Mishra B, Singh R, Reddy GBM, Patel A, Saravanan R, Gupta PK. Development of alternative approaches for in process quality control of rabies vaccine. Adv Anim Vet Sci. 2014;2:164–170. doi: 10.14737/journal.aavs/2014/2.3.164.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, Xiong Y, Luo TR, Wei YC, Nan SJ, Liu F, Pan Y, Feng L, Zhu W, Liu K, Guo JG, Li HM. Molecular epidemiology of rabies in Guangxi Province, South of China. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto S. Morphology of rabies virion and cytopathology of virus infected cells. Symp Ser Immunobiol Handb. 1974;21:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto T, Ahmed K, Karunanayake D, Wimalaratne O, Nanayakkara S. Molecular epidemiology of human rabies viruses in Sri Lanka. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;18:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mengesha AA, Hurisa B, Tesfaye T, Lemma H, Niguse D, Wold GG, Kebede A, Mesele T, Urga K. Adaptation of local rabies virus isolates to high growth titer and determination of pathogenicity to develop canine vaccine in Ethiopia. J Vaccines Vaccin. 2014;5:245. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meslin M, Koprowski H, Kaplan MM. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4. Geneva: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metlin A, Paulin L, Suomalainen S, Neuvonen E, Rybakov S, Mikhalishin V, Huovilainen A. Characterization of Russian rabies virus vaccine strain RV-97. Virus Res. 2008;132:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ming P, Dua J, Tanga Q, Yanb J, Nadin-Davis SA, Li H, Taoa X, Huangd Y, Hud R, Liange G. Molecular characterization of the complete genome of a street rabies virus isolated in China. Virus Res. 2009;143:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadin-Davis SA, Sheen M, Wandeler AI. Recent emergence of the arctic rabies virus lineage. Virus Res. 2012;163:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadin-Davis SA, Turner G, Paul JPV, Madhusudana SN, Wandeler AI. Emergence of arctic-like rabies lineage in India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:111–116. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaraja T, Madhusudana T, Desai A. Molecular characterization of the full length genome of a rabies virus isolate from India. Virus Genes. 2008;36:449–459. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nogueira YL. Rabies in McCoy cell line. Part I. Cytopathic effect and replication. Rev Inst Adolfo Lutz. 1992;52:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.OIE (World Organization for Animal Health). Rabies. In: OIE-Terrestrial Manual. 2013, pp. 1–28.

- 25.Paldurai A, Singh RP, Gupta PK, Sharma B, Pandey KD. Growth Kinetics of Rabies Virus in BHK-21 Cells using fluorescent activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis and a monoclonal antibody based cell-ELISA. J Immunol Vaccine Technol. 2014;1:103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pant GR, Lavenir R, Wong FYK, Certoma A, Larrous F, Bhatta DR, Bourhy H, Stevens V, Dacheux L. Recent emergence and spread of an arctic-related phylogenetic lineage of rabies virus in Nepal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quiambo BP, Dimaano EM, Ambas C, Davis R, Banzhoff A, Malerczyk C. Reducing the cost of post-exposure rabies prophylaxis: efficacy of 0.1 ml PCEC rabies vaccine administrated intra-dermally using the Thai Red cross post-exposure regimen in patients severely exposed to laboratory-confirmed rabid animals. Vaccine. 2005;23:1709–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy GBM, Singh R, Singh RP, Singh KP, Gupta PK, Desai A, Shankar SK, Ramakrishnan MA, Verma R. Molecular characterization of Indian rabies virus isolates by partial sequencing of nucleoprotein (N) and phosphoprotein (P) genes. Virus Genes. 2011;43:13–17. doi: 10.1007/s11262-011-0601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh NK, Meshram CD, Sonwane AA, Dahiya SS, Pawar SS, Chaturvedi VK, Saini M, Singh RP, Gupta PK. Protection of mice against lethal rabies virus challenge using short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) delivered through lentiviral vector. Mol Biotechnol. 2014;56:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s12033-013-9685-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh RP. Control strategies for peste des petits ruminants in small ruminants of India. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot. 2011;30:879–887. doi: 10.20506/rst.30.3.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayama-Ito M, Ito N, Yamada K, Sugiyama M, Minamoto N. Multiple amino acids in the glycoprotein of rabies virus are responsible for pathogenicity in adult mice. Virus Res. 2006;115:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsiang H, Atanasiu P. Replication du virus rabique fixe en suspension cellular. CR Acad Sci. 1971;272:897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. WHO technical report series no. 931. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. pp. 1–87.

- 35.WHO. WHO technical report series no. 941. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. pp. 1–96. [PubMed]

- 36.Wiktor TJ, Clark HF. Chronic rabies virus infection of cell cultures. Infect Immun. 1972;6:988–995. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.6.988-995.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]