Abstract

Objectives:

The study examined the prevalence of stress, burnout, and coping, and the relationship between these variables among emergency physicians at a teaching hospital in Kingston, Jamaica.

Methods:

Thirty out of 41 physicians in the Emergency Department completed the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Perceived Stress Scale, Ways of Coping Questionnaire, and a background questionnaire. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted.

Results:

Fifty per cent of study participants scored highly on emotional exhaustion; the scores of 53.3% also indicated that they were highly stressed. Stress correlated significantly with the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization components of burnout. Depersonalization was significantly correlated with two coping strategies: escape-avoidance and accepting responsibility; emotional exhaustion was also significantly correlated with escape-avoidance.

Conclusion:

Emergency physicians at the hospital scored high on stress and components of burnout. Interventions aimed at reducing the occupational contributors to stress and improving levels of coping will reduce the risk of burnout and enhance psychological well-being among emergency physicians.

Keywords: Burnout, coping, emergency physicians, stress

Abstract

Objetivos:

El estudio examinó la prevalencia del estrés, el desgaste profesional (burnout), y el afrontamiento, así como la relación de estas variables entre los médicos de emergencia en un hospital de Kingston, Jamaica.

Métodos:

Treinta de 41 médicos en el área de emergencias respondieron el denominado Maslach Burnout Inventory, la Escala de Estrés Percibido, el Cuestionario de Formas de Afrontamiento, y un cuestionario de antecedentes. Se realizaron análisis estadísticos descriptivos.

Resultados:

El cincuenta por ciento de los participantes en el estudio alcanzó una alta puntuación en agotamiento emocional; las puntuaciones de 53.3% también indican que estaban extremadamente estresados. El estrés guardaba una correlación significativa con los componentes de agotamiento emocional y despersonalización del burnout. La despersonalización guardaba una correlación significativa con dos estrategias de afrontamiento: huida-evitación y aceptación de la responsabilidad. El agotamiento emocional tuvo también una correlación significativa con la huida-evitación.

Conclusión:

Los médicos de emergencias en el hospital tuvieron una elevada puntuación en relación con el estrés y los componentes del burnout. Las intervenciones estuvieron dirigidas a reducir los factores ocupacionales que contribuyen al estrés. Mejorar los niveles de afrontamiento reducirá el riesgo de burnout y mejorará el estado de bienestar psicológico entre los médicos de emergencias.

INTRODUCTION

Burnout is a psychological concept used to refer to maladaptive reactions occurring over time in response to work-related stressors (1, 2). Burnout has three components: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA). Emotional exhaustion refers to feelings of being emotionally over-extended and exhausted; depersonalization is characterized by an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one's service, care, treatment, or to one's institution; personal accomplishment refers to one's feelings of competence and achievement. Having high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and low levels of personal accomplishment is indicative of burnout, which is prevalent in human-service professions where workers have to constantly interact with other people and serve their needs (1).

Emergency physicians are among those who are at greatest risk of experiencing burnout within the medical profession (3). Job demands generally characteristic of emergency medical practice include unpredictable workload, high patient attendances, limited resources, repeated exposure to traumatic events, potentially violent situations, and critical decision-making (4). In particular, physicians working in academic health centres reported higher levels of burnout than those working in non-academic health centres, being more exposed to certain factors such as more indigent patients, job insecurity and competition for research funding (5). In the Jamaican urban context, emergency physicians face these challenges in addition to social stressors such as community violence, under-resourced work facilities and high patient volume due to the generally low availability of affordable healthcare, which may increase their susceptibility to burnout (6). These job and environmental features of the local work environment indicate the importance of investigating levels of stress, burnout and coping among emergency physicians at an urban academic health centre in Kingston, Jamaica.

Stress can be defined as the emotional and physiological reactions to stressors (7, 8). According to Carter (9), the difference between stress and burnout is a matter of degree, in that stress precedes burnout and, therefore, burnout is often recognized as the end-product of prolonged stress. It must be noted that stress, in itself, does not cause burnout; however, burnout cannot exist without stress (10).

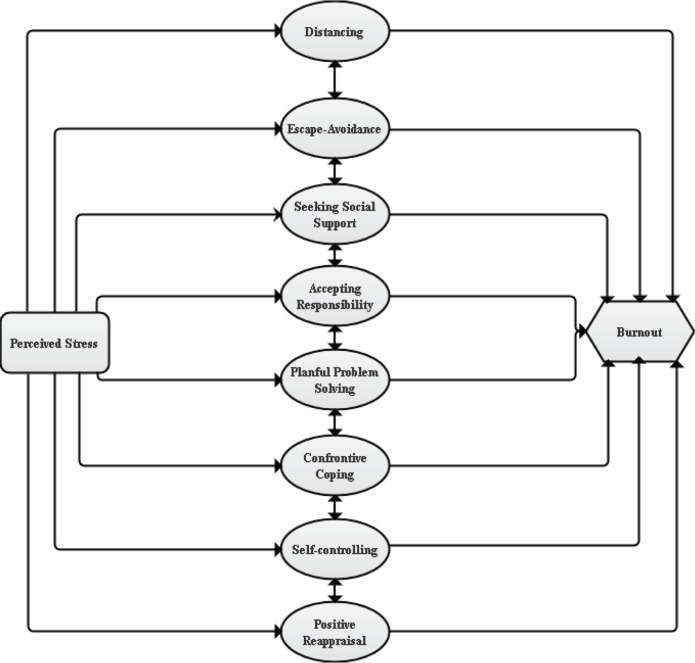

Coping has the potential to mediate the relationship between stress and burnout (Model). Coping, a person's conscious effort to deal with stressful events, may be either adaptive or maladaptive. According to Folkman and Lazarus (11), adaptive coping strategies (eg planful problem-solving and positive reappraisal) can be linked to an increase in positive emotions while maladaptive strategies (such as confrontive coping and distancing) can be linked to an increase in negative emotions.

Model 1. The stress, coping and burnout process. The model highlights a mediational relationship among the variables, suggesting that coping strategies can affect the relationship between stress and burnout, thereby resulting in either higher or lower burnout, despite the existence of stress.

Note: The coping mechanisms identified in the centre of the model are based on those that were assessed using the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (11).

Despite the positive effects of coping, the high prevalence of burnout among emergency physicians (2) suggests that they may not be engaging their coping resources or they might be using maladaptive coping strategies. It is important to investigate the experience of local emergency physicians, who may be exposed to high levels of stress, to identify the psychological effects of this exposure. Data were collected to explore the following research questions:

What is the prevalence of stress among emergency physicians?

What is the extent to which the group is experiencing burnout?

What is the relationship between stress, burnout and coping strategies?

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Thirty-seven of the 41 emergency physicians met the criteria for participating in the study (employment in the hospital's emergency department for at least one year). Of these, 30 emergency physicians participated in the study – a response rate of 81%. Questionnaires were administered to all 30 physicians.

Burnout was assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (7), a 22-item questionnaire with three subscales: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA). Each response was measured on a six-point Likert-type scale. A high degree of burnout is reflected in high scores on EE and DP and low scores on PA. Internal consistency reliability estimates for the EE, DP and PA subscales were 0.93, 0.75 and 0.68, respectively, for this study.

Stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (12), a 10-item questionnaire measuring the degree to which individuals feel events in their lives are stressful. Responses were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale. Possible scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater stress. Internal consistency reliability for the scale was 0.77.

Coping was assessed using the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (13), which measures eight commonly used coping styles: confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, planful problem solving and positive reappraisal. Responses for each item were scored on a four-point Likert-type scale, which indicates the frequency with which each strategy was used. Internal consistency reliability estimates ranged from 0.50 (accepting responsibility) to 0.80 (escape-avoidance and positive appraisal).

Data on demographic characteristics, namely: gender, level of education, the number of patients per week, the number of years working at the institution, year of graduation from medical school, job position, and type of shift were collected. Ethical approval for conducting the study was obtained from the University Hospital of the West Indies/ University of the West Indies/Faculty of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee. Data collection ensued over a period of 10 weeks during low-peak work hours and included informed consent procedures and structured interviews. Descriptive statistical analyses (percentages, means, standard deviations and correlations) were conducted using SPSS 18 for Windows.

RESULTS

Fifty-six per cent of the respondents were female while 44% were male. Most had been employed there for five years or less (59%) and 52% held a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MB BS) degree. Additionally, 66.7% were residents, 74% worked day shifts only, and for 88%, the patient load ranged from 11 to more than 30 patients per shift (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of emergency physicians.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 44.4 |

| Female | 15 | 55.6 |

| Total | 27 | |

| Level of education | ||

| MB BS | 14 | 51.9 |

| Enrolled in programme* | 7 | 25.9 |

| Graduate of programme* | 6 | 22.2 |

| Total | 27 | |

| Number of years working in Emergency Department at the hospital | ||

| 1-5 years | 16 | 59.3 |

| 6-10 years | 8 | 29.6 |

| 11-15 years | 3 | 11.1 |

| Total | 27 | |

| Job position | ||

| Consultant | 3 | 11.1 |

| Chief resident | 6 | 22.2 |

| Resident | 18 | 66.7 |

| Total | 27 | |

| Shift most frequently worked | ||

| Day shift | 20 | 74.1 |

| Night shift | 1 | 3.7 |

| Both | 6 | 22.2 |

| Total | 27 | |

| Year of graduation from medical school | ||

| 1995-1999 | 2 | 7.7 |

| 2000-2004 | 5 | 19.2 |

| 2005-2009 | 13 | 50.0 |

| 2010-2012 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Total | 26 | |

| Average daily patient responsibilities | ||

| 0-10 | 3 | 12.0 |

| 11-20 | 16 | 64.0 |

| 21-30 | 5 | 20.0 |

| More than 30 | 1 | 4.0 |

| Total | 25 | |

Postgraduate DM Emergency Medicine Programme

Stress scores ranged from three to 29, with an average perceived stress score of 15.53 (SD = 5.70). More than half (53%) of the participants reported levels of perceived stress that were above the average reported perceived stress for the group and 44% reported stress levels below the average score.

Analysis of burnout component scores showed that 70% of emergency physicians reported moderate to high levels of EE, 43% reported moderate to high levels of DP and 73% reported low to moderate levels of PA (Table 2). However, none of the physicians' scores reflected high burnout (ie high EE and DP with low PA).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of burnout components.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion (EE) | ||

| High | 15 | 50.0 |

| Moderate | 6 | 20.0 |

| Low | 9 | 30.0 |

| Depersonalization (DP) | ||

| High | 6 | 20.0 |

| Moderate | 7 | 23.3 |

| Low | 17 | 56.7 |

| Personal accomplishment (PA) | ||

| High | 8 | 26.7 |

| Moderate | 17 | 56.7 |

| Low | 5 | 16.7 |

n = 30

More adaptive coping strategies (self-controlling, seeking social support, planful problem-solving and positive reappraisal) were employed than maladaptive ones (confrontive coping, distancing and escape-avoidance). Planful problem-solving was the most frequently used strategy [M = 11.63, SD = 3.08] (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean scores for physicians on coping strategies measured by the Ways of Coping.

| Coping strategy | Mean (standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Planful problem-solving | 11.63 (3.08) |

| Self controlling | 10.97 (3.29) |

| Positive reappraisal | 9.23 (4.44) |

| Seeking social support | 8.83 (3.53) |

| Escape-avoidance | 7.80 (5.26) |

| Distancing | 7.37 (3.11) |

| Confrontive coping | 6.43 (3.65) |

| Accepting responsibility | 5.57 (2.33) |

n = 30

Bivariate correlational analyses found stress was significantly correlated with two components of burnout: emotional exhaustion (r (28) = 0.60, p < 0.01) and depersonalization (r (28) = 0.38, p < 0.05); however, there was no significant relationship between stress and personal accomplishment. Similarly, two components of burnout were significantly related to two coping strategies: depersonalization was significantly correlated with escape-avoidance (r (28) = 0.46, p < 0.05) and accepting responsibility (r (28) = 0.40, p < 0.05); emotional exhaustion was significantly correlated with escape-avoidance (r (28) = 0.40, p < 0.05).

Regression analyses failed to support a mediational relationship among stress, coping and burnout. Only stress remained significantly related to EE (p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The findings confirm high levels of perceived stress among a significant number of emergency physicians at a teaching hospital in urban Jamaica. This stress exposure is consistent with high levels of stress reported among emergency physicians elsewhere (4–6). The prevalence of high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization among the group indicates that emergency physicians are vulnerable to the effects of stress. The job demands being experienced by these emergency physicians (heavy workload, role conflict, interpersonal conflicts and demanding work hours) are similar to those found to be predictive of emotional exhaustion (4). In addition, previous work on the stress-burnout relationship is supported by the current findings; the fact that stress was most strongly correlated with EE, out of all the components of burnout, supports previous work indicating that EE is the central component of burnout and the most prevalent consequence of stress (4, 10).

The results may indicate that emergency physicians are not consistently engaging adaptive coping resources, which may explain the high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization among the group. Furthermore, the significant correlation between escape-avoidance and these two components of burnout supports what previous studies have shown, which is that the use of maladaptive coping strategies, like escape-avoidance, are associated with negative emotions (11). Similarly, the significant and positive correlation between accepting responsibility and depersonalization showed that the physicians who used this coping strategy were more likely to distance themselves from the human and individuating features of their patients, perhaps in an effort to minimize their own anxiety.

These results confirm the importance of examining the risk and protective factors influencing well-being among emergency physicians. However, the small sample size of the current inquiry precluded a test of the conceptual model to determine the precise mechanisms whereby the levels of stress, coping and burnout may be related. Future research should examine pathways of effect as well as context-specific stressful job demands and their relationship to levels of stress and burnout among a larger group.

It is important to determine if there are coping resources not assessed in the current study that are being used by emergency physicians to facilitate their resistance to the potentially debilitating effects of stress. The inclusion of local and culturally specific coping resources in future assessment could aid in achieving this. Also, due to the cross-sectional design of the current study, it is impossible to determine the long-term effects of their stressful work environment on this relatively highly educated and mostly recently-hired group of emergency physicians who mostly work on day shifts. A prospective longitudinal assessment would be useful to establish if the vulnerabilities identified here worsen over time.

Overall, this study underscores the urgent need for policy-driven structural modifications to reduce occupational stressors facing emergency physicians, as well as the value of group and personal interventions to enhance their stress management and coping efforts. Such responses will reduce emergency physicians' susceptibility to the effects of stress and their risk of burnout, proving invaluable for their personal well-being, as well as for the enhanced quality of healthcare delivery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maslach C, Schaulefi BW, Leiter PM. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murat K, Ozcan K. Burnout syndrome at the emergency service. Scand J Trauma Resusc. 2006;14:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical-care health workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:482–488. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole TR, Carlin N. The suffering of physicians. Lancet. 2009;374:1414–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindo JLM, McCaw-Binns A, LaGrenade J, Jackson M, Eldemire-Shearer D. Mental wellbeing of doctors and nurses in two hospitals in Kingston, Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:153–159. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychology Press, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd C, King R, Chenoweth L. Social work, stress and burnout: a review. J Ment Health. 2002;11:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter S. Where do you fall on the burnout continuum? [Internet] Psychology Today 2012. [cited 2013 Nov]. Available from: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/high-octane-women/201205/where-do-you-fall-the-burnout-continuum.

- 10.Evans-Turner T, Milner P, Mirfin-Veitch B, Gates S, Higgins N. The Maslach Burn-out Inventory and its relationship with staff transition in and out of the intellectual disability workforce; Paper presented at the Seventh New Zealand Association for the Study of Intellectual Disability Conference; 2010 Aug 24-26; Dunedin, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:466–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of coping questionnaire sampler set: manual, test booklet, scoring key. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]