Abstract

We report a case of a retired soldier who was severely injured by an explosion in 1993 during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Among other wounds, he suffered an explosive wound in the lumbosacral spine with steel foreign body (shrapnel). A year after primary wound treatment, a purulent fistula appeared which was treated and stopped with antimicrobial therapy. Subsequently, the fistula was activated several times after the antibiotic therapy was discontinued, but in the last eight years, the fistula had been continuously present so the patient decided on surgery. During surgery, the shrapnel was removed from the lumbosacral spine and there was debridement of necrotic bone. During two weeks of peri-operative and postoperative period, chronic osteomyelitis was treated by intravenous ciprofloxacin and gen-tamycin, and after that by a combination of rifampicin and trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole orally, for six months. The patient did not show any signs of infection after two years of follow-up.

Keywords: Chronic osteomyelitis, lumbosacral spine, shrapnel

Abstract

Reportamos el caso de un soldado retirado que fue gravemente herido por una explosión en 1993 durante la guerra en Bosnia y Herzegovina. Entre otras lesiones, sufrió una herida en la columna lumbosacra producida por un cuerpo extraño de acero (metralla) proveniente de un explosivo. Un año después del tratamiento primario de la herida, apareció una fístula purulenta que fue detenida con terapia antimicrobiana. Posteriormente, la fístula se activó varias veces después de que la terapia antibiótica fue descontinuada, pero en los últimos ocho años, la fístula ha estado continuamente presente, así que el paciente se decidió por someterse a cirugía. Durante la cirugía, la metralla fue extraída de la columna lumbosacra, con desbridamiento de hueso necrótico. Durante las dos semanas del período perioperatoria y postoperatorio, la osteomielitis crónica fue tratada con ciprofloxacina intravenosa y gentamicina, y luego con una combinación de rifampicina y trimetoprim-sulfametoxazol por vía oral, durante seis meses. El paciente no mostró ningún signo de infección después de dos años de seguimiento.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral fracture from an explosive injury is often treated by operation [spine stabilization] (1, 2) while penetrating explosive spine wounds are not. In a smaller number of patients with penetrating injury of the thoracolumbar spine and unstable fracture, debridement and fusion with or without spinal decompression are indicated (3). World literature and experience from the Croatian Patriotic War (1–4) have shown that projectile instruments can be removed when possible.

The index patient was suffering from chronic osteomyelitis of the lumbosacral spine with a purulent fistula for sixteen years, with few remissions, until he decided to have surgery.

CASE REPORT

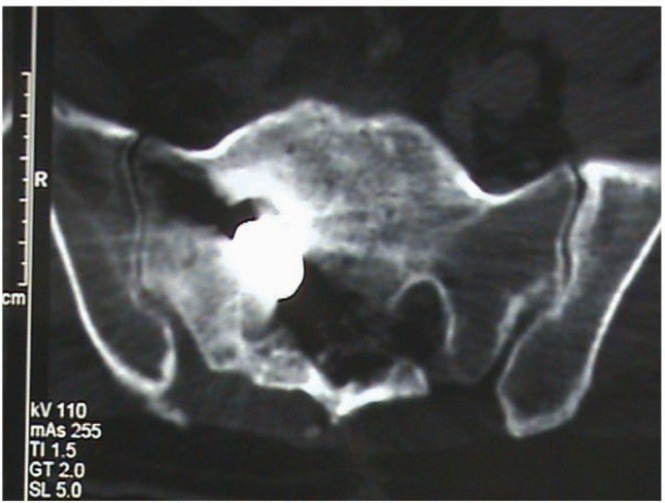

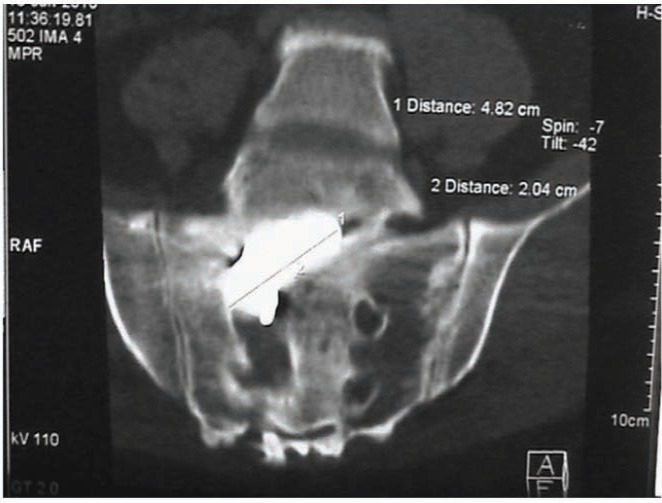

A retired 44-year old soldier was admitted in the Clinical Department of Neurosurgery because of a purulent fistula due to an explosive wound to his lumbosacral spine, 17 years ago (1993) during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was wounded during the military action when he stepped on anti-personnel mine. He suffered the traumatic amputation of the right leg, an explosive wound to the medial side of the left thigh and the traumatic amputation of the distal phalanx of the index finger of the right hand. His lumbosacral spine was also injured by the penetration of steel foreign body [shrapnel 4 × 2 cm] (Figs. 1–3).

Fig. 1. Lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine, showing the metallic foreign body (shrapnel) after an explosive wound.

Fig. 3. Computed tomography scan and axial view, the same as Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 2. Computed tomography scan and anteroposterior view, showing the same shrapnel as Fig. 1.

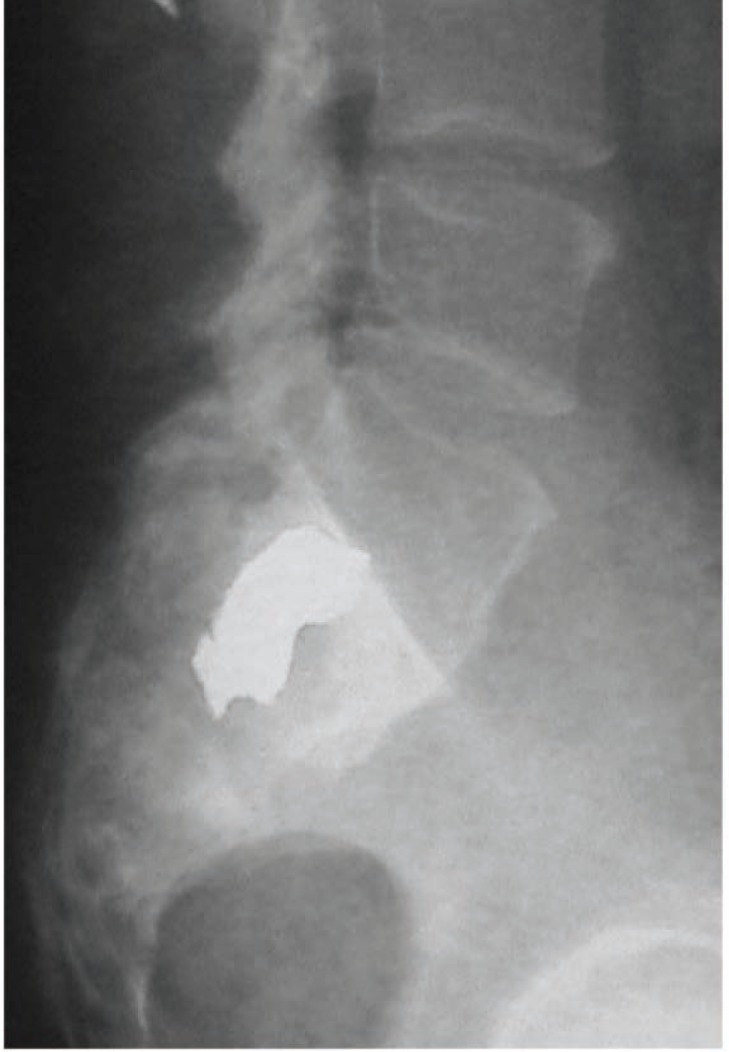

In 1993, his wounds were treated by several operations and antibiotic therapy during prolonged hospitalization but the shrapnel had not been removed. After that, he was discharged from the hospital for physical and social rehabilitation. After one year, a purulent fistula appeared for the first time, close to the scar above the lumbosacral spine. It was treated conservatively with antibiotic therapy in a local hospital in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the purulent secretion stopped. The same situation repeated itself several times – every time after the antibiotic therapy was discontinued. In the last eight years before admission to the clinical department, the purulent fistula was continuous (Fig. 4) so the patient decided to have an operation to remove the metallic foreign body from his lumbosacral spine. Throughout the 17 years, there was no sign of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula or meningitis.

Fig. 4. Preoperative local status.

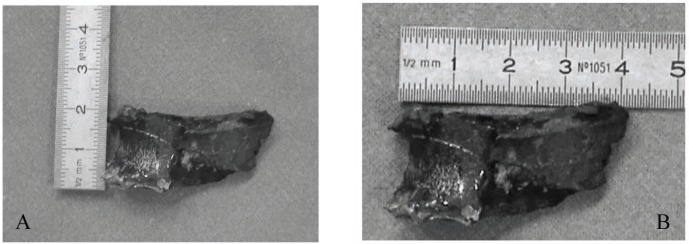

Preoperatively, the patient was in good condition, afebrile, haemodynamically stable and eupnoic. He had surgery under general anaesthesia in the prone position. Necrotic tissue in all layers was excised. Necrotic bone was removed by high speed drilling and the shrapnel extracted (Fig. 5A-B). Near to the shrapnel, burned pieces of military uniform and fibrous tissue reaction were seen.

Fig. 5A-B. The extracted shrapnel.

For the first two postoperative days, there was no sign of purulent drainage but it appeared on the third day. It was eliminated by aggressive rinsing of the surgical wound with the usual antiseptic solutions (hydrogen peroxide, saline and betadine) for a week. During the surgery, a sample of pus was sent for microbiological analysis and methicillinsensitive Staphylo-coccus aureus (MSSA) was cultured. This was susceptible to ciprofloxacin and gentamycin so the patient was treated by the intravenous route for the next two weeks.

Microbiological analysis also demonstrated susceptibility to cloxacillin, azithromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, mupirocin and cotrimoxazole and resistance to benzylpenicillin.

The patient was discharged from hospital to continue oral treatment for chronic osteomyelitis with trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole 960 mg twice a day and rifampicin 300 mg twice a day for the next six months. After four months of oral therapy, the control examination showed the following results: sedimentation rate was 4 mm, C-reactive protein was normal, and bone scintigraphy showed no accumulation of the isotope in the lumbosacral spine. After two years of the follow-up period, the patient remains without infection and is doing well.

DISCUSSION

We reported a case of a patient, a former soldier who was wounded by an explosive injury, with residual shrapnel in the lumbosacral spine which caused chronic osteomyelitis. It recurred several times after discontinuation of antibiotic therapy. Some authors report the possibility of reactivation of osteomyelitis after the initial antibiotic treatment (5, 6).

Tissues surrounding a missile wound are in a state of constant change (7). It is therefore advisable to extract shrapnel and bone fragments in order to prevent infection.

A chronic fistulous osteomyelitis after explosive injuries was also reported during the Vietnam War (8). After an explosive penetrating wound, a metallic foreign body should be extracted if it is possible because it is well known that even after the antibiotic treatment of the open fracture, staphylococci can remain resistant in injured tissue and cause chronic osteomyelitis (9). On the other hand, the optimal length of the oral antibiotic therapy had not been established (10). However, therapy with rifampicin alone is not advisable because it induces resistance in staphylococci within 24 hours if administered alone (11). Consequently, dual systematic antimicrobial therapy with chinolones such as ciprofloxacin and rifampicin, carried out for three to six months is recommended (12). It is believed that after the initial intravenous therapy, prolonged oral dual therapy (rifampicin + fluoroquinolone, clindamycin or trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole) can achieve a good clinical result (13). After surgery and removal of the shrapnel, there was initial intravenous therapy for two weeks with ciprofloxacin and gentamycin. After that, treatment was by the combination of rifampicin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole orally, for six months. The patient remained clinically well at two years.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell RS, Vo AH, Neal CJ, Tigno J, Roberts R, Mossop C, et al. Military traumatic brain and spinal column injury: a 5-year study of the impact blast and other military grade weaponry on the central nervous system. J Trauma. 2009;4:104–111. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d88c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ragel BT, Allred CD, Brevard S, Davis RT, Frank EH. Fractures of the thoracolumbar spine sustained by soldiers in vehicles attacked by improvised explosive devices. Spine. 2009;22:2400–2405. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b7e585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter BK, Groth AT, Kuklo TR. Penetrating thoracolumbar spine injuries. Curr Opin Orthop. 2005;3:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rukovanjski M. Spinal cord injuries caused by missile weapons in the Croatian war. J Trauma. 1996;35:1895–1925. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603001-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens QEJ, Seibly JM, Chen YH, Dickerman RD, Noel J, Kattner KA. Reactivation of dormant lumbar methicillin-resistant Staphylo-coccus aureus osteomyelitis after 12 years. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eylon S, Mosheiff R, Liebergall M, Wolf E, Brocke L, Peyser A. Delayed reaction to shrapnel retained in soft tissue. Injury. 2005;36:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakorafas GH, Peros G. Principles of war surgery: current concepts and future perspectives. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witschi T, Omer G. The treatment of open tibial shaft fractures from Vietnam war. J Trauma. 1970;10:105–105. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson NE. Infections associated with war: the American forces experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2008;30:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munoz P, Bouza E. Acute and chronic adult osteomyelitis and prosthesis-related infections. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:129–147. doi: 10.1053/berh.1999.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frommelt L. Principles of systematic antimicrobial therapy in foreign material associated infection in bone tissue, with special focus on periprosthetic infection. Injury. 2006;37:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daver NG, Shelburne SA, Atmar RL, Giordano TP, Stager CE, Reitman CA, et al. Oral step-down therapy is comparable to intravenous therapy for Staphylococcus aureus osteomylitis. J Infect. 2007;54:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]