Abstract

Objective:

Suicide is one of the major social issues in Japan. According to a report of the National Policy Agency, there were approximately 22 000 to 24 000 annual suicides between 1994 and 1997 and there have been over 30 000 annual suicides in Japan since 1998. For these reasons, we think it is important to discuss the economic factor related to suicides in recent years.

Method:

In this study, we examined suicide rates and the average disposable income per household in Japan in the last 15 years (ie 1994–2008) and discussed the statistical analysis of the average disposable income per household and the associated suicide rates.

Results and Discussion:

During the research period, annual suicide rates per 100 000 population in Japan ranged from 16.9 to 25.5 among the total population, from 23.1 to 38.0 among men, and from 10.9 to 14.7 among women. The annual average disposable income per household (ten thousand yen) ranged from 424.0 to 549.9. The average disposable income per household was related to the suicide rate among the total population and among men. The average disposable income per household was not related to the suicide rate among women.

Conclusion:

We believe that this discussion will be useful in developing specific suicide preventive measures.

Keywords: Average disposable income, Japan, slump, suicide

Abstract

Objetivo:

El suicidio es uno de los principales problemas sociales en Japón. Según un informe de la Agencia Nacional de Políticas, hubo aproximadamente de 22000 a 24000 suicidios anuales entre 1994 y 1997, y ha habido más de 30000 suicidios anuales en Japón desde 1998. Por estas razones, creemos que es importante analizar el factor económico relacionado con suicidios en los últimos años.

Método:

En este estudio, examinamos las tasas de suicidio y el ingreso disponible promedio por hogar en Japón en los últimos 15 años (es decir, 1994 – 2008), y discutimos el análisis estadístico del ingreso disponible promedio por hogar y las tasas de suicidio asociadas.

Resultados y discusión:

Durante el período de investigación, las tasas de suicidio anual por 100000 habitantes en Japón, se extendieron de 16.9 a 25.5 entre la población total, de 23.1 a 38.0 entre los hombres y de 10.9 a 14.7 entre las mujeres. El ingreso disponible promedio anual por hogar (10 mil yenes) varió de 424.0 a 549.9. El ingreso disponible promedio por hogar guardó relación con la tasa de suicidio entre la población total y entre los hombres. El ingreso disponible promedio por hogar no estuvo relacionado con la tasa de suicidio entre las mujeres.

Conclusión:

Creemos que esta discusión será útil en el desarrollo de medidas preventivas específicas contra el suicidio.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a problem in many parts of the world, and studies have examined the issue from various viewpoints (1–3). According to a report of the National Police Agency as edited by the Cabinet Office (4), the annual number of suicides in Japan from 1994 to 1997 ranged from 21 679 to 24 391 among the total population, from 14 560 to 16 416 among men, and from 7119 to 7975 among women. Further, the average number of suicides during that four-year period was approximately 22 905 among the total population, approximately 15 311 among men, and 7594 among women. The number of suicides in 1998 was 32 863, comprising 23 013 and 9850 suicides among men and women, respectively. The annual suicide rates in Japan have been over 30 000 since then.

In Japan, trends in the number of suicides and traffic fatalities are often compared. The annual number of traffic fatalities within 24 hours of a traffic accident was fewer than 10 000 in 1996 and approximately 4000 in 2010 (5). The annual number of traffic accidents was approximately 950 000 in 2004 and fewer than 700 000 in 2011 (5). In recent years, both the number of traffic accidents and fatalities have decreased, indicating the effectiveness of recent traffic safety measures (5). In the discussion of these numbers, suicide is one of the major social issues in Japan, and effective suicide prevention programmes are being sought to decrease the number of suicides. For that purpose, the suicidal risk factors have been clarified and it is important that specific suicide prevention measures for the factors be determined. A discussion of the present suicide prevention programme in New Zealand was also one of the planned prevention measures (6).

The causes of suicides vary, however, the most common causative factor of suicide among the elderly in Japan is “suffering from physical illness” (7). Ono also described that “health problems” accounted for nearly half of the suicides in Japan (8). One of the authors of the studies on the biological and climate factors contributing to suicide (9, 10) noted that not only psychosocial factors but also genetic and biological factors may contribute to suicide. A decrease in serotonin, a neurotransmitter in the brain, was indicated in suicidal high-risk patients with unusual levels of the noradrenalinα2A receptor and the resulting changes in the information-communication system were indicated in suicides in many studies (9). This report also described that some studies showed a relationship between low cholesterol and suicide and between malfunction of the hypothalamushypophysis-adrenal cortex (HPA) system and suicide but there have also been reports by authors who disagreed with these opinions. In the study about the relationship between suicide and climate issues (10), we discussed the correlation between the age-adjusted suicide rate and five climate issues (mean air temperature, mean sea level air pressure, mean relative humidity, total of sunshine duration, and total of precipi-tation) in Japan as a whole, and in each of the five prefectures with the highest and lowest suicide rates. We found that age-adjusted suicide rates had a significant inverse correlation with mean air temperature in all prefectures with the highest suicide rates and in the three prefectures with the lowest suicide rates among women, that age-adjusted suicide rates had a significant correlation with mean relative humidity in the three prefectures with the highest suicide rates among women, and that age-adjusted suicide rates had a significant correlation with total of sunshine duration in the three prefectures with the highest suicide rates among women. One report described that the rapid increase of the number of suicides in Japan among middle-aged men was influenced by the economic slump in 1998 (11). There are also reports that the economic problem has influenced the rapid increase in the number of suicides in recent years (8, 12). Abe et al reported on the result of correlation of economic slump and suicide method (13). There are also reports about the relationship between unemployment and suicide (8, 14). We reported that stock prices may be related to suicide rates among men (15), and there are other reports discussing this issue from a socio-economic viewpoint (16, 17). We believe that it is necessary to examine economic factors as they relate to suicide. Therefore, we examined the relationship between suicide and disposable income in Japan.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

In the present study, we examined the annual rate of suicides in Japan from 1994 to 2008 as reported in the vital statistics of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as edited by the Cabinet Office (4) and the average disposable income per household in Japan during the same period as detailed in the National Livelihood Survey of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (18). The relationship between the average disposable income per household and the suicide rate during the period was assessed using single regression analysis in an Excel spreadsheet. Disposable income refers to what remains after statutory deductions such as income, residence and fixed property taxes as well as social insurance payments have been deducted from income (19).

RESULTS

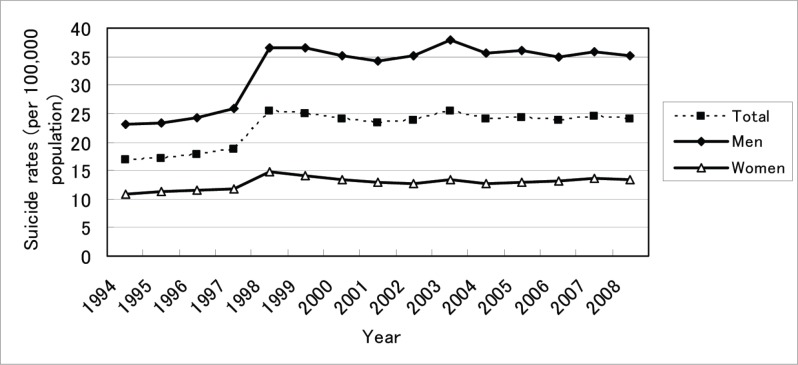

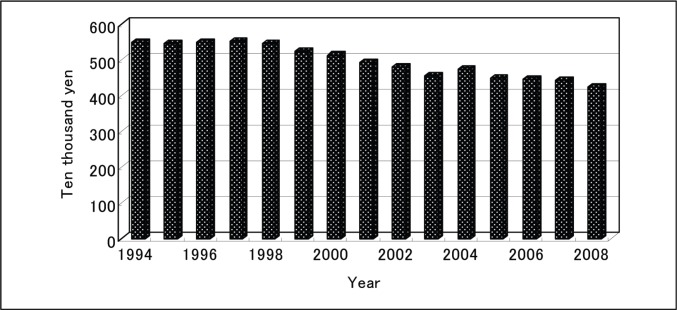

The annual rate of suicides in Japan during the research period is shown in Fig. 1. The rate per 100 000 population during the research period ranged from 16.9 to 25.5 among the total population, from 23.1 to 38.0 among men and from 10.9 to 14.7 among women. The annual average disposable income per household in Japan during the research period is shown in Fig. 2 and the disposable income (ten thousand yen) ranged from 424.0 to 549.9.

Fig. 1. The annual rate of suicides in Japan from 1994 to 2008.

Fig. 2. The annual average disposable income per household in Japan from 1994 to 2008.

The correlation coefficient between the suicide rate and the average disposable income per household was r = -0.642 among the total population, r = -0.681 among men, and r = -0.437 among women. The result of the relationship between the average disposable income per household and the suicide rate was R2 = 0.4122, p = 0.010, and y = -0.0438x + 44.246 among the total population, R2 = 0.4632, p = 0.005, and y = -0.0802x + 72.358 among men, and R2 = 0.1908, p = 0.104, and y = -0.0102x + 17.921 among women.

DISCUSSION

In the present discussion, the average disposable income per household was related to the suicide rate among the total population and among men while the average disposable income per household was not related to the suicide rate among women. The focus, therefore, was on the relationship between the average disposable income per household and the increase of suicide among men. Fujioka et al reported that the social stress factors of suicide among men were occupational and economic problems, whereas problems of human relationships including families were shown by the research of one prefecture of Japan (20) to be the social stress factors of suicide among women.

A study of one Japanese town showed that the main stressors were ‘economic matters' and ‘job' among men and ‘interpersonal relations' among women (21). Another report noted that economic and life problems among middle-aged men were a serious matter in the trend of increasing suicides in Japan since 1998 and that there must be honesty in sharing of information as part of the support programmes in suicide prevention (22).

Matsuki et al described that the features of economic problems among patients attempting suicide were “among slightly advanced age group and men”, “the psychiatry consultation rate was low in the group”, and “heterogeneity was high among the other factors” (23). Hitomi et al reported that the features of suicide attempting persons with economic reason as the causative factors in their research were ‘men', ‘middle-aged' and ‘mood disorders or adjustment disorders' (24), and they concluded that it was necessary to carry out early detection and treatment continuously for depression during an economic slump, and it was important to educate coworkers and family members about the pre-depressive state that such a slump can cause. We think that economic slump and unemployment increase stress. Lack of social support raises the suicidal risk of people with economic problems (25). Therefore, support systems and the concrete preventive measures in organizations promoting suicide prevention are important (25, 26).

We conclude that citizens and organizations devoted to suicide prevention including administration and medicine should discuss prevention measures for suicide based on economic items, including those described here.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nowers MP. Suicide by drowning in the bath. Med Sci Law. 1999;39:349–353. doi: 10.1177/002580249903900414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindqvist P, Johansson L, Karlsson U. In the aftermath of teenage suicide: a qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:26–26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Suicide attempts after psychiatric care. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63:132–139. doi: 10.1080/08039480802422677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabinet Office Heisei22nenban jisatsutaisakuhakusho. 2010:185–185. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue K, Fukunaga T, Okazaki Y, Nishimura M, Fujita Y. A study on the effectiveness of recent traffic accident prevention measures based on trends in the number of traffic accidents in Japan: specific measures for the future based on recent conditions. West Indian Med J. 2013;62:571–571. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2012.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi Y. Suicide prevention strategies overseas. Jpn J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;33:1591–1595. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshioka N. Epidemiological study of suicide in Japan: is it possible to reduce committing suicide? Jpn J Legal Med. 1998;52:286–293. [in Japanese, English abstract] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono Y. Suicide prevention program in Japan. Psychiatry. 2006;8:365–368. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirakawa O. Biological factors associated with suicide. Psychiatry. 2006;8:359–364. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue K, Nishimura Y, Fujita Y, Ono Y, Fukunaga T. The relationship between suicide and five climate issues in a large-scale and long term study in Japan. West Indian Med J. 2012;61:532–537. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2010.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho Y. Psychopathology of middle-aged suicide. Bessatsuigakunoayumi. 2003:19–22. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Fukunaga T, Okazaki Y, Fujita Y, Abe S, Ono Y. Causes of suicide in middle-aged men in prefectures in Japan during the recent spike in suicides. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:342–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe R, Shioiri T, Nishimura A, Nushida H, Ueno Y, Kojima M, et al. Economic slump and suicide method: preliminary study in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:213–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2003.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki A, Sakai R, Shirakawa T. Low income, unemployment, and suicide mortality rates for middle-age persons in Japan. Psychol Rep. 2005;96:337–348. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.2.337-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue K, Fukunaga T, Okazaki Y. Study of an economic issue as a possible indicator of suicide risk: a discussion of stock prices and suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57:783–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagendra Gouda M, Rao SM. Factors related to attempted suicide in davanagere. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:15–18. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talala KM, Huurre TM, Laatikainen TK, Martelin TP, Ostamo AI, Prättälä RS. The contribution of psychological distress to socio-economic differences in cause-specific mortality: a population-based follow-up of 28 years. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:138–138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.E-Stat. [[cited 2011 Nov 16]]. Available from http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL02010101.do [in Japanese]

- 19.Health and Welfare Statistics Association J Health Welfare Stat. 2008;55:132–132. [Sekaitoukeino nenjisuii] [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujioka K, Abe S, Hiraiwa K. Life time social, psychological and physical background of suicides: research on the number of suicides during a year in Fukushima prefecture. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2004;106:17–31. [in Japanese, English abstract] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto Y, Shimoji A, Sakamoto K, Yoshida T, Takizawa T, Watanabe N. A research study of the mental health literacy for suicide prevention in Asagiri-cho, Kumamoto pref. Jpn J Ment Health. 2010;25:75–87. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto T, Katsumata Y, Kitani M, Takeshima T. Raifusutejiniokeru topikkusu Chuunenno jisatsu. Seisinkarinshousarbisu. 2008;8:276–279. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuki M, Matsuki H, Horikawa N. Clinical examinations about suicide attempts prompted by “economic problems”. Jpn J Psychiatric Treatment. 2011;26:633–642. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitomi Y, Tamura Y, Mukai T, Hitomi K, Sakata I. Investigation about suicide attempts following economical reasons. Jpn J Gen Hos Psychiatry. 2004;16:250–256. [in Japanese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otsuka K, Sakai A, Yambe T, Endo J, Iwato S, Koeda A, et al. Aftercare for suicide attempts. Jpn J Psychiatric Treatment. 2011;26:1247–1254. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue K, Nishimura Y, Nishida A, Fukunaga T, Masaki M, Fujita Y, et al. Relationships between suicide and three economic factors in South Korea. Leg Med. 2010;12:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]