Abstract

This paper presents a simple procedure for clinical trials comparing several arms to control. Demand for streamlining the evaluation of new treatments has led to Phase III clinical trials with more arms than would have been used in the past. In such a setting, it is reasonable that some arms may not perform as well as an active control. We introduce a simple procedure that takes advantage of negative results in some comparisons to lessen the required strength of evidence for other comparisons. We evaluate properties analytically, and use them to support claims made about multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) designs.

Keywords: Comparisons with control; Multi-arm, multi-stage (MAMS) design; Multiple comparisons; Family-wise error rate (FWE); Sequentially rejective methods; Estimation bias

1 Introduction

1.1 A Simple Proposal

Imagine a clinical trial comparing, say, 4 active arms to a control with respect to a continuous outcome for which large values are good. The Bonferroni method requires a given p-value to be α/4 to declare significance. Is it valid instead to eliminate arms whose z-scores with control are negative, and then adjust for the number of positive z-scores with control? For instance, if only 2 of the 4 comparisons with control result in positive z-scores, can we drop the poorly performing arms and use α/2 for the two promising comparisons? The proposal seems reasonable, yet if it were valid, would it not be used all of the time?

1.2 Background

It is not new to use results of some comparisons to reduce the degree of evidence required for other comparisons. For example, Holm’s sequentially rejective Bonferroni method [1] first orders the p-values from different comparisons and sequentially reduces the evidence required according to the following algorithm. If the smallest of m p-values, p(1), is larger than the Bonferroni value α/m, no comparisons are declared significant. However, if p(1) < α/m, that comparison is declared significant and the second smallest p-value is compared to α/(m – 1). Loosely speaking, the reasoning is that either a mistake was made in rejecting the hypothesis corresponding to p(1) or not; if there was a mistake, then, in terms of the family-wise error rate, the error has been made and the next decision is irrelevant. On the other hand, if no mistake was made, then at most m – 1 null hypotheses could be true. Similarly, if p(2) < α/(m – 1), then p(3) is compared to α/(m – 2), etc. This method reduces the level of evidence required for some comparisons provided that the best performing arms are doing very well. In other words, the strong showing of the best performing arms allows reduction of the threshold for lesser performing arms. Holm’s method is one example of a chain procedure that redistributes alpha from statistically significant comparisons to the remaining comparisons [2-3]. The procedure described in Section 1.1 approaches this concept from the other direction: the poor performance of some arms might allow use of a less stringent threshold for the best performing arms.

The proposal in Section 1.1 is simply a single-stage version of multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) designs for phase II testing with multiple potential treatment regimens or doses. Some of these modify boundaries for remaining arms after dropping inferior arms, while others do not. Magirr et al’s [4] (see also [5]) extension of the Dunnett procedure to accommodate monitoring and early stopping for efficacy or futility does not lessen the evidence required after dropping inferior arms. They provide expressions for power and expected sample size, and show that the familywise error rate is strongly controlled. References [6-10] lessen the evidence once inferior arms are dropped for failing to meet a specified minimum threshold. They argue that using a fixed threshold is fundamentally different from selecting the best among a set of arms, and requires less onerous adjustment for multiplicity at the end. Their focus has often been in phase II development in which strict control of the family-wise error rate is less of a concern than missing potentially promising treatments. Nonetheless, it begs the question of whether a similar methodology can be used in phase III trials requiring careful attention to multiplicity adjustment.

1.3 Goal of This Paper

The focus of our paper is two-fold. First, we believe the simple approach described in Section 1.1 offers advantages over commonly used methods of comparing multiple arms with control. Second, the mathematics behind the simple procedure is easier than that behind MAMS designs that lessen the evidence for remaining comparisons after dropping inferior arms. Simulation is often used to evaluate operating characteristics of MAMS designs because of their complexity. Analytic results from the simple design can be used to corroborate and help understand the claims of MAMS proponents that less adjustment is needed when one uses a fixed threshold rather than picking the best among a set of arms.

We use the following notation throughout.

m is the number of active arms that are compared to control with respect to a continuous, normally distributed outcome with common variance σ2 across arms.

Unless otherwise stated, n is the common sample size in each arm, which we take to be large enough to treat the standard deviation as known. Section 7 discusses the setting in which the control sample size is R times an active arm sample size.

b is the z-score threshold for retaining arms; arms with Zi > b are retained, where b = 0 for most of the paper.

k is the number of z-scores comparing active arms with control that exceed b.

2 Attempt to Justify The Procedure

It is instructive to scrutinize an attempt to justify the proposed procedure on mathematical grounds because it illustrates that there can be subtle errors in reasoning even for relatively simple arguments. This underscores the need to corroborate theoretical justifications with simulation results.

The following reasoning seems to show that the family-wise error rate (FWE), the probability of at least one false positive, is protected by the procedure in Section 1.1 applied in a two-tailed testing setting. For known standard deviation σ and constant c, consider the event that ∣Zi∣ > c, where is the z-score comparing arm i to control. When we discard the negative z-scores, the conditional distribution of each remaining z-score is that of (∣Zi∣ ∣Zi > 0). The null distribution of Zi is symmetric about 0, so the distribution of ∣Zi∣ is unaltered by knowing that Zi > 0. Therefore, the conditional probability that ∣Zi∣ > c given that Zi > 0 is just its unconditional probability Pr(∣Zi∣ > c) = 2{1 – Φ(c)}. If k of the z-scores are positive, it seems that we could test each at α/k and the Bonferroni inequality would imply that the conditional type I error rate given k positive z-scores is controlled at level α. That is, we set c = ck, where ck solves 2{1 – Φ(ck)} = α/k. That is, ck = Φ−1{1– α/(2k)}. If the conditional type I error rate is controlled at level α, so is the unconditional type I error rate. Two problems with this reasoning are 1) the fact that the procedure transfers all of the conditional type I error rate from two tails to one tail and 2) the procedure does not control the conditional type I error rate at level α. We elaborate on each of these problems below.

The transfer of α from a 2-tail to 1-tail test comes from the fact that by throwing out negative z-scores, we have no possibility of rejecting the null hypothesis for harm. Therefore, even if the conditional type I error rate were α = 0.05, the test would have conditional error rates of 0 and 0.05 in the left and right tails instead of the conventional 0.025 in each tail.

The more serious problem is that the conditional type I error rate is not controlled at level α. For example, with m = 5 active arms and a placebo, suppose that all 5 z-scores are positive. The conditional type I error rate given 5 positive z-scores is approximately 0.10 instead of 0.05. How could such a seemingly simple argument that the distribution of ∣Zi∣ is unaffected by Zi > 0 be wrong? Although the conditional distribution of ∣Zi∣ is unaffected by the knowledge that Zi > 0, it is affected by knowledge that Zj > 0 for j ≠ i. When all 5 of the z-scores are positive, the control arm probably has a much smaller than usual sample mean, which affects all comparisons. If the different z-scores were independent, then the above reasoning would have been correct.

Although the attempt to justify the procedure revealed some flaws, we can modify the method to protect the family-wise error rate at level α, as discussed in the next section.

3 Improving the Procedure

3.1 Adjusting the Bonferroni Alpha Level

Because of the alpha transfer issue, we restrict ourselves from now on to one-tailed tests. Consider first the following hypotheses.

| (1) |

where δi = μi – μ0. Note that this null hypothesis assumes that no treatment is actually harmful. We will modify this later. We are interested in whether the use of the critical value

| (2) |

the upper α/k quantile of the standard normal distribution, controls the one-tailed FWE at level α. Unlike the two-tailed error rate, the one-tailed error rate is not controlled using (2) even for independent comparisons because the distribution of Zi is affected by knowledge that Zi > 0. This does not necessarily mean that the FWE is not controlled for our correlated z-scores. Also, the fact that the conditional type I error rate can be large does not preclude the unconditional error rate from being controlled. After all, the conditional error rate can sometimes be very small as well. For instance, if no z-score is positive, the conditional type I error rate is 0. Thus, the unconditional type I error rate, which is the conditional type I error rate averaged over the distribution of the number of positive z-scores, might still be controlled at level α.

Under the assumption that no treatment is harmful, the worst case null configuration of means is the global null hypothesis that none of the m active population means differ from control. The appendix shows that the FWE under the global null hypothesis is

| (3) |

The resulting FWEs are shown in Table 1. Notwithstanding the failed attempt to justify the procedure on theoretical grounds, the FWEs are all either less than or very close to the targeted values. For any given m, we can determine the alpha level α’ to use to control the FWE under the global null hypothesis. Table 1 implies that when m = 2, we must use a slightly more stringent alpha level α’ < α, whereas when m = 5, we can use a less stringent alpha level α’ > α and still control the FWE under any null configuration of means.

Table 1.

FWE for the one-tailed procedure using (2) under the global null hypothesis that the m active means equal the control mean.

| m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α = 025 | .0261 | .0253 | .0244 | .0237 |

| α = .050 | .0529 | .0513 | .0493 | .0474 |

Alternatively, we can determine the level such that the use of level on the k positive z-scores controls the FWE under the global null hypothesis that all m active means equal the control mean. We used a grid search as follows. For each potential alpha value in the grid, we used Expression (3), where , to find the FWE. We then determined as the value whose FWE was closest to .025 or .05. Table 2 shows the results. For example, suppose we want to control the FWE at level 0.025, and there are k positive z-scores. Then we would use level 0.0240/k for the positive z-scores if m = 2, but 0.0264/k if m = 5.

Table 2.

such that applying level to the k positive z-scores controls the FWE when the total number of active arms is m.

| m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α = 025 | .0240 | .0247 | .0256 | .0264 |

| α = .050 | .0473 | .0488 | .0507 | .0527 |

It is preferable to consider hypotheses of the form

| (4) |

rather than of the form (1) to allow the possibility of a harmful treatment. In that case we would not be able to use a less stringent value α’ > α when m = 5. To see this, suppose that all but the first two active arms are actually so harmful that their sample means are virtually guaranteed to be less than the control sample mean. Then the FWE under δ1 = 0, δ2 = 0, δ3 = δ4 = δ5 = −∞ corresponds to the m = 2 entry of Table 1. Therefore, if we are to have any hope of controlling the FWE strongly, meaning that the probability of at least one false rejection is α or less irrespective of the true mean configuration, we must use level α’/k, where α’ is the most conservative value, . Table 2 shows that for m ≤ 5,

| (5) |

to achieve an FWE of at most .025 or .05, respectively. That is, for a one-tailed test at FWE 0.025 or 0.050, reject a null hypothesis if its p-value is less than or equal to α’/k = 0.0240/k or 0.0473/k, respectively, where k is the number of positive z-scores with control. Given that appears to be a decreasing function of m when the sample sizes in the different arms are equal, the values in (5) would be expected to work for larger m as well. However, this should be verified for the given m before using the procedure.

An open question is whether the procedure controls the FWE strongly under hypothesis (4). We evaluated the FWE by simulation of a million trials for m = 2, 3, 4, 5 (and by numerical integration for m = 2), and found using a grid search that the FWE is maximized when δi = 0 for all i. Unfortunately, a proof of strong control under hypothesis (4) eludes us. The logical attempt to prove strong control is to show that the probability of at least one rejection increases in δi for fixed values of other δs. Proving this is difficult because increasing δi increases the probability that the arm i mean will exceed control, which makes it harder to declare other means significant.

3.2 Sequentially Rejective Version

We can improve the procedure by using a sequentially rejective version as follows. Suppose that there are k positive z-scores with control. Let p(1) < p(2) < … < p(k) be their ordered p-values.

If p(1) > α’/k, stop and declare no arm different from control. If p(1) < α’/k, declare the arm associated with p(1) to be different from control and proceed to step 2.

Compare p(2) to α’/(k – 1). If p(2) > α’/(k – 1), stop, whereas if p(2) ≤ α’/(k – 1), declare the arm associated with p(2) to be different from control and proceed to step 3.

Compare p(3) to α’/(k – 2), etc.

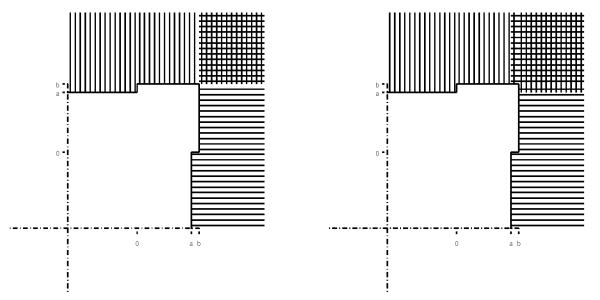

Figure 1 shows the rejection region for the original version (left) and sequentially rejective version (right) of our procedure for m = 2. Clearly, the sequentially rejective version is always at least as powerful as the original version for any m. The appendix contains a proof of the fact that the sequentially rejective version strongly controls the FWE under hypothesis (1).

Figure 1.

Rejection region for m = 2 for the original method without sequential rejection (left) and the sequentially rejective method (right). Horizontal (vertical) lines indicate rejection of hypothesis 1 (hypothesis 2), and a = Φ−1(1 – .024) = 1.98 and b = Φ−1(1 – .024/2) = 2.26.

A referee pointed out that power can be improved even further by using instead of α’. For instance, with m = 5, suppose that 4 z-scores are positive (i.e., k = 4). We can compare the smallest p-value to (from Table 2) instead of α’/4 = .0240/4. If the smallest p-value is significant, we compare the second smallest to .0247/3 instead of .0240/3, etc. The improvement is small when m ≤ 5, but is more substantial for larger m.

4 Power

Consider two different scenarios. Under Scenario 1, only one of the active population means differs from control, while under Scenario 2, all of the active population means are greater than control by the same amount. Our procedure should enjoy a power advantage over the ordinary Bonferroni procedure under Scenario 1. The rationale is as follows. Under Scenario 1, the number of positive z-scores with control among the m – 1 ineffective active arms is k if and only if the control arm is the m – kth order statistic among the m arms whose population means are the same (including the control). Because the control is equally likely to be any of the m order statistics among the arms with equal population means, the number k of positive z-scores among the ineffective non-control arms is equally likely to be 0, 1, … , m–1. If k is small, our method will require much less adjustment than Bonferroni, resulting in a considerable power advantage.

Our procedure should have a very slight disadvantage under Scenario 2 if all active population means are much greater than control. In this case we are likely to have to adjust for all m comparisons, so we lose a small amount of power because we use level α’/m instead of α/m for the ordinary Bonferroni. The slight loss of power is a small price to pay for a potentially large gain in power under the more realistic scenario that only one of several alternative active regimens is effective.

The above intuition is confirmed by simulation and numerical integration results. The appendix derives the following power formulas for our procedure under Scenarios 1 and 2, respectively:

| (6) |

| (7) |

In these formulas, θ is the expected z-score comparing an active arm to control. In equation (6), θ is the expected z-score for the one active arm that has an effect, while in equation (7), it is the common expected z-score for all active arms. Also, ck is the critical value Φ−1(1 – α/k) corresponding to adjustment for the k arms whose z-scores with control are positive.

Table 3 compares the power of our original and sequentially-rejective procedures to Bonferroni, Dunnett [11], and Hochberg [12] procedures when the power for a two-arm trial would have been approximately 0.85. As expected, our method outperforms the others when there is a single good arm, whereas Hochberg performs better if all arms are equally effective.

Table 3.

Power of different procedures that strongly control the FWE. In Scenario 1, only one arm has a treatment effect. In Scenario 2, each arm has the same effect. The size of the effect is selected to make the power for an unadjusted two-group comparison approximately 85%.

| m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | ||||

| Bonferroni | .776 | .728 | .692 | .664 |

| Dunnett | .785 | .742 | .712 | .688 |

| Hochberg | .774 | .726 | .692 | .663 |

| Our original | .824 | .803 | .783 | .766 |

| Our seq. rej. | .824 | .803 | .783 | .765 |

| Scenario 2 | ||||

| Bonferroni | .776 | .728 | .692 | .664 |

| Dunnett | .785 | .742 | .712 | .688 |

| Hochberg | .831 | .813 | .797 | .781 |

| Our original | .771 | .723 | .687 | .659 |

| Our seq. rej. | .819 | .796 | .776 | .757 |

5 Bias in Estimation

There is a question about whether one must worry about bias in treatment effect estimates. In phase I-II settings, some authors have argued against the need for bias adjustment for multi-arm multi-stage designs (MAMS) [10]. One reason is that treatment effects in all arms will be reported, so the focus is not just on the arms that meet the threshold. Nonetheless, it is natural in a phase III setting to emphasize results in the arms that meet the threshold. In such a case, the question of how much bias might be present if we consider only the arms whose z-scores with control exceed 0 is relevant. Clearly Z > 0 gives information about the treatment effect, so it is strange to condition on this information; we usually condition on ancillary statistics, not informative statistics. Nonetheless, it would be reassuring if the amount of bias is small.

Unfortunately, bias depends not just on the population mean in the selected arm, but on the population means in the other arms as well. For instance, in a trial with m = 5 active arms, suppose that all 5 z-scores are positive. If we knew that most of the arms were truly ineffective, 5 positive z-scores would suggest that the control sample mean is lower than average. On the other hand, under Scenario 2, it would be expected to see most or all z-scores positive, so there might be very little bias. Given that we will not know the population means of other arms, it is reasonable to calculate bias by conditioning only on the comparison in question. That is, we calculate . The appendix shows that this bias is given by

where δ is the treatment effect relative to control. Suppose that δ is such that a two-armed trial has power 1 – β. This means that δ/(2σ2/n)1/2 ≈ zα + zβ, where zτ denotes the 100(1–τ)th percentile of a standard normal distribution. Then bias and relative bias are

| (8) |

The relative biases assuming that the true δ corresponds to different powers for a two-armed trial are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relative bias (percent) in estimating δi = μi – μ0 if arm i meets the threshold Zi > 0; the true δi is such that the power for a two-armed trial is as shown in row 1.

| Power | .50 | .55 | .60 | .65 | .70 | .75 | .80 | .85 | .90 |

| Bias (%) | 9.1 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

Thus, if the true treatment effect is such that the power is approximately 85%, the relative bias is only about 0.6%

6 Example

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial compared three diets with respect to blood pressure changes from baseline among approximately 150 participants per arm. The diets were: 1) Fruits and Vegetables: rich in fruits and vegetables 2) Combination: rich in fruits and vegetables and low-fat dairy products, and reduced in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol, and 3) Control diet thought to be similar to what many Americans eat. The primary outcome of DASH was change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to the end of the eight week diet period. However, there was secondary interest in the effects of the diets on triglycerides and other factors.

We use our procedure to compare the diets with respect to the change in triglycerides from baseline to the end of the study at a one-tailed alpha of 0.05. The means and standard deviations of changes in the three diets are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Baseline minus end of study triglycerides for each of the three diets in the DASH trial.

| n | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 145 | −3.255 | 35.343 |

| Fruits and Vegetables | 146 | 5.082 | 38.634 |

| Combination | 146 | −6.808 | 35.713 |

Positive values indicate higher triglycerides at baseline than at the end of the study, and are therefore good. The t-statistics for fruits and vegetables versus control and combination versus control were +1.920 and −0.853, respectively. We treat these as if they were z-scores because the numbers of degrees of freedom for the t-statistics are very large (nearly 300). Because only one t-statistic was positive, our procedure uses α/1 = 0.05 for the test comparing the fruits and vegetables diet versus control. The one-tailed p-value of 0.028 is statistically significant. If we had used the ordinary Bonferroni, Holm sequentially rejective Bonferroni, or Hochberg procedures, we would not have been able to declare a benefit with respect to triglycerides at the one-tailed 0.05 level.

7 A Warning About Different Thresholds or Sample Size Ratios

The procedure of adjusting only for the number of comparisons that are promising works well despite the fact that that attempts to justify it on theoretical grounds fail. Eliminating z-scores that are less than 0 just happens to work out for the equal sample size case. Other possible thresholds may not work. For instance, Table 6 shows the FWE if we use a Bonferroni adjustment for the number of z-scores that exceed b for different choices of b. We see that when b > 0, the FWE can be considerably higher than the intended rate of 0.025.

Table 6.

FWE for Bonferroni adjusting for the number of z-scores that exceed b. The intended level is α = .025.

| b | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | .0232 | .0223 | .0216 | .0210 |

| −2 | .0232 | .0223 | .0216 | .0210 |

| −1.00 | .0235 | .0224 | .0217 | .0211 |

| −0.75 | .0237 | .0227 | .0219 | .0213 |

| −0.50 | .0242 | .0231 | .0223 | .0217 |

| −0.25 | .0249 | .0239 | .0230 | .0224 |

| 0 | .0261 | .0253 | .0244 | .0237 |

| 0.25 | .0277 | .0275 | .0268 | .0260 |

| 0.50 | .0299 | .0307 | .0305 | .0299 |

| 0.75 | .0324 | .0350 | .0358 | .0359 |

| 1.00 | .0352 | .0402 | .0428 | .0441 |

| 2.00 | .0409 | .0561 | .0691 | .0806 |

| 3.00 | .0026 | .0038 | .0050 | .0061 |

Thus far we have considered equal sample sizes, but power for comparisons with control is maximized when the sample size ratio R of control to an active arm is m1/2 [13]. Enlarging the control sample size decreases the correlation between z-statistics, which necessitates using a smaller value of α’ than shown in (5) to maintain an α level procedure. For instance, for m = 5, we must use α’ = .0200/k to achieve a one-sided FWE of .025 or less. Note also that α’ decreases as a function of m, in contrast to the equal sample size case. In practice we have found that even though a ratio of m1/2 to 1 maximizes power, trialists often prefer less extreme ratios for at least two reasons: 1) comparisons among active arms are also of interest, so reducing active arm sample sizes too much is undesirable, and 2) patients may prefer to have a reasonably high probability of being assigned to a new therapy rather than the standard. Whatever ratio R is used, one can use Formula (10) to determine ck = Φ−1(1 – α’/k), and therefore .

8 Discussion

There is an increased emphasis on conserving resources and speeding up the process of finding good treatments by evaluating multiple regimens in a single Phase III trial. This is likely to result in some treatments performing worse than the control, particularly when the control is an active comparator. The procedure of adjusting only for comparisons whose z-scores are in the intended direction is simple and has desirable properties in such a setting. Another appealing setting is that of secondary endpoints for which there is less of an expectation of benefit. Whenever there is a reasonable expectation of negative results for some comparisons, one can parlay those negative results into higher power for remaining comparisons while maintaining control of the family-wise error rate. We showed when only one arm is truly effective relative to control, there are power advantages over other procedures such as Bonferroni, Holm’s sequentially rejective Bonferroni, and Hochberg’s procedure. These sequentially rejective methods bank on positive results from certain comparisons to lower the degree of evidence required in other comparisons, and perform well when multiple arms are truly effective. In contrast, our method banks on negative results of certain comparisons to lower the degree of evidence required in other comparisons.

Our method is simple enough to permit closed form expressions for the FWE and power, and therefore allow easy verification of some claims about more complicated multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) designs. Some proponents of such designs have claimed that because they are eliminating arms that fail to meet a fixed threshold rather than picking the best among a set of treatments, much less adjustment is needed to account for multiplicity. We can verify using numerical integration the veracity of this claim for a single-stage procedure using a threshold of Z > 0 and equally sized arms. The conservatism of Bonferroni balances out the anti-conservatism of eliminating negative z-scores, so the FWE is almost controlled with no further adjustment. The fact that it is not completely controlled without a slight further adjustment highlights that seemingly correct arguments like those in Section 2 can be flawed and should be verified by simulation. It is important to note that when the control arm is larger than other arms, the correlation among z-scores decreases, and more of an adjustment for multiplicity is needed.

Bias in estimation is a more difficult issue because bias for a given comparison depends on the population means of all arms. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to compute bias from being among the arms meeting the threshold Z > 0. We showed with a closed form expression that the bias is ignorably small in realistic cases.

One peculiarity of the procedure is that adjusting for the number of positive z-score mean that Z = −0.001 requires adjustment, whereas Z = 0.001 does not. This is an unavoidable consequence of using a threshold.

Because our procedure is simple, has small bias, and enjoys a power advantage over competitors when several arms are expected to be ineffective, we recommend its use in such settings.

Table 7.

α’ required for allocation ratio .

| m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α = 025 | .0224 | .0212 | .0205 | .0200 |

| α = .050 | .0441 | .0416 | .0402 | .0393 |

A Appendix

A.1 FWE under the Global Null

Consider the case where an arm is retained if its z-score exceeds b. Let ck = Φ−1(1 – α’)/k be the critical value corresponding to k z-scores with control that exceed b. We compute the null probability P(k) that k arms pass through the b-threshold and at least one is statistically significant. Assume first equal sample size n in each arm. Without loss, we take the common true means to be 0 and the standard error of to be 1 for each i. We calculate the probability that the first k, and only the first k, of the m active sample means pass the b-threshold, and at least one is significant. We then multiply by to account for the fact that the means passing the b-threshold could have been any set of k from the m to write P(k) as

where Maxk and Maxm–k are the maxima of and , respectively, and Mink is the minimum of . Now condition on the control sample mean and integrate over its distribution to see that P(k) is:

where , , and .

Now use the fact that , and is the probability that are all between and . Therefore P(k) is

To get the FWE we must now sum over k:

| (9) |

Similar calculations show that when each active arm sample size is R times the control sample size, the formula for FWE is

| (10) |

A.2 Power

We can compute power under Scenario 1 that all but one active mean is null as follows. Assume again, without loss, that the standard error of is 1, and that the control population mean is 0. Let the lone nonzero active population mean be , where θ is the expected z-score comparing that arm, which we can take to be arm 1, to control.

Consider first the event that exactly k – 1 of the z-scores comparing arms 2, … , m to control pass the b-threshold, and the arm 1 z-score exceeds ck. Using similar reasoning as above, we can show that the probability of this event is

Therefore, power is obtained by summing over k:

| (11) |

Similarly, we can compute power under Scenario 2 that all active population means equal as follows. We compute the power to declare a given arm, say arm 1, significant.

Consider first the event that exactly k – 1 of the z-scores comparing arms 2, … , m to control pass the b-threshold, and the arm 1 z-score exceeds ck. Using similar reasoning as above, we can show that the probability of this event is

Therefore, power is obtained by summing over k:

We have defined power as the probability of correctly declaring a difference for a given pairwise comparison, but also of interest is the probability of at least one correct rejection. Under Scenario 1, this definition agrees with the first definition because only one arm is truly effective. Under Scenario 2, each arm is equally effective, in which case we can compute this second definition of power as follows. The distribution of the z-scores under the hypothesis that each has mean θ is the distribution of Z1 + θ, … , Zm + θ, where Z1, … , Zm are the corresponding z-scores when E(Zi) = 0. The probability that exactly k of Z1 + θ, … , Zm + θ exceed b is the probability that exactly k of Z1, … , Zm exceed b – θ. Conditioned on , this probability is

| (12) |

Given this event, the probability that at least one of Z1, … , Zk exceeds ck is the probability that at least one of exceeds given that all exceed . This probability is

| (13) |

Multiplying Expressions (12) and (13) and integrating over the distribution of gives an expression for the probability of at least one rejection under the alternative hypothesis that all z-scores have mean θ:

| (14) |

A.3 Bias in Estimation

The bias of our procedure that requires Zi > b to retain arm i is as follows.

| (15) |

When b = 0, this expression simplifies to

A.4 Proof of Strong Control of FWE with Sequentially Rejective Version When No Treatment is Harmful

Without loss, assume that the active population means that are equal to the control are in arms 1, 2, … r; i.e., μ1 = μ0, … μr = μ0, whereas μr+1 > μ0, … , μm > μ0. We will prove that the sequentially rejective version of our procedure satisfies Pr(at least one of arms 1, 2, … , r is rejected) ≤ α.

Assume first that r = m. Given k positive z-scores, the original and sequentially rejective procedures both declare at least one arm significant iff p(1) < α’/k. Thus, they have the same conditional type I error rate. It follows that they both have the same unconditional FWE as well.

Now suppose that r < m. If arms r + 1, … , m had not been included in the trial, the FWE would have been controlled by the argument above. But inclusion of arms r + 1, … , m can only make the critical values for Z1, … , Zr larger. Therefore, the FWE among arms 1, … , r must be controlled as well.

The same argument works for the improved version using instead of (see discussion at the end of Section 3.2). As long as is decreasing in k, the procedure is a shortcut for the closed test, which is known to control the FWE strongly [14].

References

- 1.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretz F, Maurer W, Brannath W, Posch M. A graphical approach to sequentially rejective multiple test procedures. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:586–604. doi: 10.1002/sim.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burman CF, Sonesson C, Guilbaud O. A recycling framework for the construction of Bonferroni-based multiple tests. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:739–761. doi: 10.1002/sim.3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magirr D, Jaki T, Whitehead J. A generalized Dunnett test for multi-arm multi-stage clinical studies with treatment selection. Biometrika. 2012;99:494–501. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wason JM, Jaki T. Optimal design of multi-arm multi-stage trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31:4269–4279. doi: 10.1002/sim.5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royston P, Parmar MK, Qian W. Novel designs for multi-arm clinical trials with survival outcomes with an application in ovarian cancer. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:2239–2256. doi: 10.1002/sim.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parmar MK, Barthel F, Sydes M, Langley R, Kaplan R, Eisenhauer E, Brady M, James N, Bookman MA, Swart A, Qian W, Royston P. Speeding up the evaluation of new agents in cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1204–1214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sydes MR, Parmar MK, James ND, Clarke NW, Dearnaley DP, Mason MD, Morgan RC, Sanders K, Royston P. Issues in applying multi-arm multi-stage methodology to a clinical trial in prostate cancer: the MRC STAMPEDE trial. Trials. 2009;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royston P, Barthel F, Parmar MK, Choodari-Oskoooei B, Isham V. Designs for clinical trials with time-to-event outcomes based on stopping guidelines for lack of benefit. Trials. 2011;12:81. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips PJ, Gillespie SH, Boercee M, Heinrich N, Arnoutse R, McHugh T, Pletschette M, Lienhardt C, Hafner R, Mgone C, Zumla A, Nunn A, J., Hoelscher M. Innovative trial designs are practical solutions for improving the treatment of tuberculosis. Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205:S250–S257. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunnett CW. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1955;50:1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunnett CW. New tables for multiple comparisons with a control. Biometrics. 1964;20:482–491. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hommel G, Bretz F, Maurer W. Powerful short-cuts for multiple testing procedures with special reference to gatekeeping strategies. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26:4063–4073. doi: 10.1002/sim.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]