Abstract

Objectives

To define inpatient care of obese children with or without an obesity diagnosis.

Study design

A total of 29 352 inpatient discharges (18 459 unique inpatients) from a tertiary children's hospital were analyzed. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured height and weight. “Obesity” was defined as BMI ≥95th percentile by using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts. “Diagnosed obesity” was defined by primary, secondary or tertiary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for “obesity” or “overweight.” Analyses controlled for multiple inpatient records per individual.

Results

A total of 5989 discharges from the hospital (20.4%) were associated with obesity, but only 512 discharges (1.7%) indicated obesity as a diagnosis. An obesity diagnosis identified only 5.5% of inpatient days for obese inpatients. Obese patients with an obesity diagnosis (Ob/Dx) had fewer hospital discharges per person and shorter lengths of stay than obese patients without an obesity diagnosis (Ob/No Dx). Patients with Ob/Dx had higher odds of mental health, endocrine, and musculo-skeletal disorders than non-obese inpatients, but Ob/No Dx patients generally did not.

Conclusions

Inpatient obesity diagnoses underestimate inpatient utilization and misidentify patterns of care for obese children. Extreme caution is warranted when using obesity diagnoses to study healthcare utilization by obese children.

Childhood obesity is increasingly prevalent, with nearly 20% of 12- to 19-year-old children classified as obese.1 These children and adolescents are at risk for developing metabolic and other complications, some of which may require inpatient treatment. Overweight and obese adults experience greater inpatient utilization and health care expenditures than adults of normal weight,2,3 but limited information exists for obese children and adolescents about the utilization of inpatient care.

Existing studies of inpatient utilization associated with obesity in children frequently rely on administrative databases and a discharge diagnosis of obesity to identify obese individuals.4 However, it is unclear whether this provides an accurate reflection of actual inpatient utilization of resources by obese children. At Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, the patient's height and weight are recorded in the electronic medical record for each inpatient stay, enabling the calculation of body mass index (BMI) for all individuals, regardless of inpatient diagnosis. The goal of this study was to determine total and diagnosis-specific inpatient utilization patterns for patients who have a measured BMI that identifies them as obese compared with patients with a clinician-assigned diagnosis of obesity.

METHODS

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a 468-bed facility including 251 general medical/surgical, 109 intensive care unit, 62 psychiatry, and 46 rehabilitation/long-term care beds. It is the only provider of tertiary pediatric medical and psychiatric care within a 50-mile radius of Cincinnati, Ohio.

CCHMC inpatient data from July 1, 2003, until April 30, 2007 (fiscal years 2004-partial 2007; n = 63 657 inpatient records), were obtained from the hospital data center, after obtaining approval for the study from the CCHMC Institutional Review Board. Data included unique medical record number, sex, race, date of birth, date of admission, height, weight, length of stay, and primary, secondary, and tertiary discharge diagnosis International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Beginning in October 2003, the hospital implemented an automated system to prompt the entry of patient height at each inpatient stay, enabling the calculation of BMI. Patient age was calculated from date of birth and date of admission.

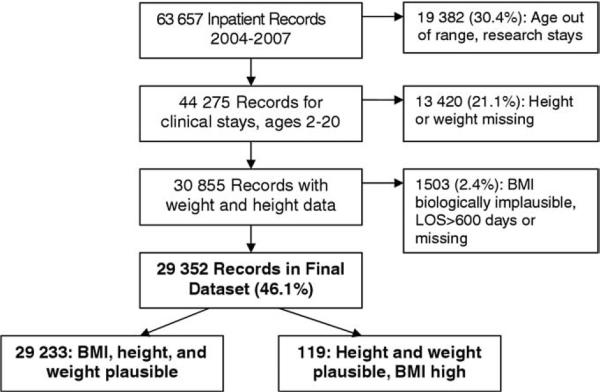

Inpatient stays for individuals <2 years or >20 years old were excluded, as were admissions designated as research (rather than clinical) discharges or discharges without a recorded length of stay. In addition, 1 visit for a child with an obesity diagnosis was excluded, with an outlier length of stay of 607 days. A flowchart depicting data cleaning for the final analysis set (n = 29 352 inpatient records; 18 459 unique individuals) is found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Compilation of final dataset.

BMI was calculated from patient height and weight, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 Growth Charts were used to determine age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles.5 To identify and eliminate obvious data entry errors, biologic plausibility of height, weight, and BMI data were determined by using World Health Organization standards for identifying outliers in anthropometric data.6

Four mutually exclusive classifications of inpatient obesity were considered, on the basis of the presence or absence of diagnosed obesity or measured obesity. Diagnosed obesity was identified as inpatient records with a primary, secondary, or tertiary discharge ICD-9 code of 278.00, 278.01, or 278.02, corresponding to “obesity not otherwise specified,” “morbid obesity,” or “overweight,” regardless of BMI. Obesity7 was identified as inpatient records with a valid, measured BMI ≥95th percentile, regardless of discharge diagnosis. Four groups could then be identified: neither measured nor diagnosed obesity (Non-Ob reference group), diagnosed obesity without obesity (Dx/Non-Ob), obesity without an obesity diagnosis (Ob/No Dx), and obesity with an obesity diagnosis (Ob/Dx).

The Clinical Classification System (CCS) was used to classify diagnosis-specific care, using discharge ICD-9-CM codes.8 This multi-level classification system developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project8 identifies 18 broad (level-1) categories of care, on the basis of systems of the body and defined with sets of ICD-9-CM codes. Each level-1 category of care can then be subdivided into more refined level-2 classifications, which include more limited sets of diagnoses. Data are reported for all CCS level-1 categories with at least 500 primary diagnoses (approximately 2% of all discharge records) in the analysis set. In addition, 5 mental health level-2 categories with at least 350 primary diagnoses are reported (eg, affective disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, preadult disorders, and other mental conditions).

Statistical Analysis

All data analysis was conducted with SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Unadjusted pair-wise differences in clinical characteristics by obesity category were determined by using χ2 analysis, unpaired t tests or analysis of variance, as appropriate. Discharges per person were calculated for each unique medical record number, and then analyzed by obesity category using general linear modeling, with adjusted least squares means plus or minus 95% CI reported. Because the same unique individual may contribute multiple inpatient discharges to the dataset (range, 1-57 discharges), the remaining data were analyzed using repeated measures analyses to allow for correlations in the inpatient discharges for the same individual. Differences in average length of stay by obesity category, accounting for multiple inpatient discharges per individual, were determined using adjusted least squares means from repeated measures analysis of variance using PROC MIXED. The adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% CI of having a primary diagnosis within a specific CCS category of care (versus all other categories) were calculated using generalized estimating equations with PROC GENMOD. All adjusted models included patient age, sex, and fiscal year of hospital discharge. Data are presented as means plus or minus SD, AOR (95% CI), or adjusted mean (95% CI). P values ≤.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Children aged 2 to 20 years with a BMI ≥95th percentile accounted for 5989 inpatient hospital discharges (20.4%) from 2004 to 2007 (Table I). However, only 512 inpatient stays (1.7%) were associated with any diagnosis of obesity. Of these, 42 (8.2%), 175 (34.2%), and 295 (57.6%) stays had a primary, secondary, or tertiary diagnosis of obesity, respectively. Four hundred seventy-five (92.8%) of these stays were for individuals classified as obese at the time of the stay.

Table I.

Characteristics of inpatient discharges by obesity category

| BMI <95th percentile |

BMI ≥95th percentile |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Non-Ob | Dx/Non-Ob | Ob/No Dx | Ob/Dx |

| N (%) inpatient discharges | 23 326 (79.5) | 37 (0.1) | 5514 (18.8) | 475 (1.6) |

| N unique individuals* | 15 228 | 36 | 3732 | 429 |

| Total inpatient days | 146 750 | 305 | 43 116 | 2523 |

| Age (years ± SD)† | 10.8 ± 5.2 | 13.3 ± 3.5§ | 11.4 ± 4.9§ | 14.4 ± 3.1§¶ |

| Sex (% female)† | 49.7 | 81.1§ | 49.3 | 59.2§¶ |

| Race (% white)† | 72.3 | 56.8 | 66.3§ | 61.5§¶ |

| BMI percentile (mean ± SD)b | 52.6 ± 30.9 | 84.3 ± 15.0§ | 97.9 ± 1.4§ | 98.9 ± 0.98§ |

| Primary Dx obesity, N (%) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 0 | 41 (8.6) |

| Secondary Dx obesity, N (%) | 0 | 10 (27.0) | 0 | 165 (34.7) |

| Tertiary Dx obesity, N (%) | 0 | 26 (70.3) | 0 | 269 (56.6) |

| Average discharges per individual‡ | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.03 ± 0.2§ | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4§ |

| Average length of stay, days (mean ± SD)‡ | 5.3 ± 10.4 | 8.4 ± 17.5§ | 6.8 ± 17.1 | 5.0 ± 7.8 |

Total number of unique inpatients by group (n = 19 425) does not equal total unique inpatients in dataset (n = 18 459) because some unique individuals have inpatient discharges classified in >1 group.

Calculated on the basis of average of all discharges.

Calculated on the basis of average of unique individuals' data.

Significantly different from Non-Ob reference group (P ≤ .05).

Significantly different from Ob/No Dx (P ≤ .05).

A diagnosis of obesity had only an 8% sensitivity rate to detect patients who were obese according to their BMI; however, the specificity rate was very high, at 99.8%. In addition, patients who were diagnosed with obesity very often were also obese (positive predictive value, 92.8%), but lack of a diagnosis of obesity did not predict BMI classification well (negative predictive value, 80.9%). Overall accuracy of an obesity diagnosis was 81.1%.

Total Inpatient Utilization

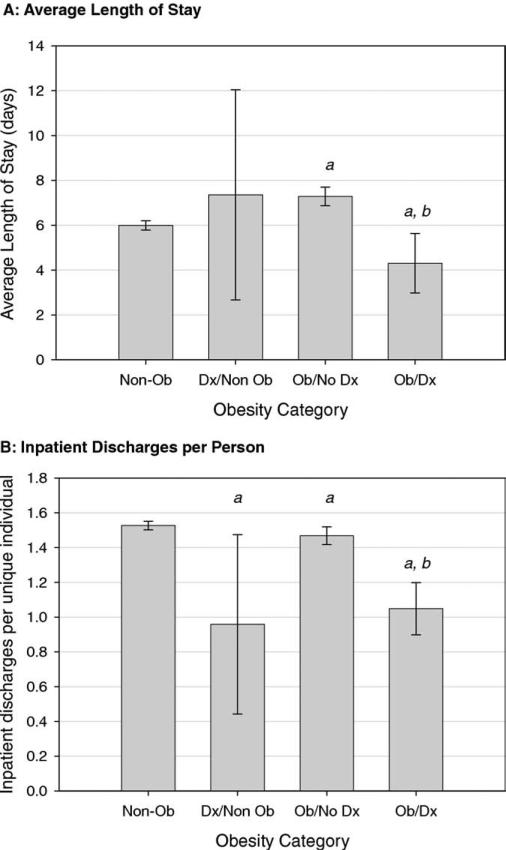

As expected, the low sensitivity of an obesity diagnosis resulted in many fewer inpatient stays (475 versus 5514), unique inpatients identified (429 versus 3732), and total in-patient days (2523 versus 43 116) in the Ob/Dx group than in the Ob/No Dx group (Table I). However, both the number of inpatient stays per unique individual and the average inpatient length of stay also differed depending on obesity classification (Figure 2). Hospital discharges per unique individual were significantly lower for all obesity categories compared with those for the Non-Ob reference (all P < .05), and hospital discharges per person for the Ob/Dx group were significantly lower than those of the Ob/No Dx group (P < .0001). The Ob/Dx group also had significantly shorter inpatient stays than the Non-Ob group (P < .0001), but the Ob/No Dx group had longer lengths of stay than the Non-Ob group (P = .01).

Figure 2.

Inpatient utilization by obesity category. A, Adjusted mean length of stay ± 95% CI from mixed models, adjusted for sex, age, and fiscal year and accounting for multiple inpatient stays per unique individual. a: significantly different from Non-Ob (P ≤ .01), b: significantly different from Ob/No Dx (P < .0001). B, Number of inpatient stays per unique individual. Adjusted means ± 95% CI from general linear modeling, adjusted for sex, age, and fiscal year. a: significantly different from Non-Ob (P ≤ .05), b: significantly different from Ob/No Dx (P < .0001).

Diagnosis-specific Utilization

Table II highlights important differences in utilization patterns between obese inpatients with a diagnosis of obesity (Ob/Dx) and obese patients without a diagnosis of obesity (Ob/No Dx). Because the number of hospital discharges in the Dx/Non-Ob category was small, this group was not analyzed for disease-specific utilization. Endocrine disorders were significantly under-represented in inpatients with Ob/No Dx (AOR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91). However, in the Ob/Dx group, endocrine diagnoses appeared to be significantly over-represented (AOR, 2.99; 95% CI, 2.36-3.78), even when excluding obesity as a primary diagnosis (AOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.20-2.29). In addition, no significant differences existed between the Ob/No Dx group and Non-Ob inpatients for nervous system, injury/poisoning, genitouri-nary, or signs/symptoms primary diagnoses. However, the Ob/Dx group appeared to be significantly protected from these primary diagnosis categories. Finally, skin/subcutaneous disorders were 30% more common in the Ob/No Dx group versus Non-Ob inpatients, but this difference was not evident for the Ob/Dx group.

Table II.

Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for specific primary diagnosis categories, by obesity category compared with non-obese reference group

| Total inpatient discharges (%) | Ob/No Dx* |

Ob/Dx* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 5514 | n = 475 | ||

| Mental health | 7635 (26.2) | 1.06 (0.98-1.13) | 1.35 (1.16-1.56) |

| Respiratory system | 3790 (13.0) | 0.97 (0.89-1.07) | 0.93 (0.68-1.27) |

| Nervous system | 2508 (8.6) | 1.03 (0.92-1.14) | 0.45 (0.27-0.76) |

| Injury and poisoning | 2422 (8.3) | 1.03 (0.92-1.15) | 0.22 (0.11-0.42) |

| Digestive system | 2376 (8.2) | 0.80 (0.71-0.90) | 0.68 (0.48-0.96) |

| Endocrine/Metabolic | 2015 (6.9) | 0.80 (0.69-0.91) | 2.99 (2.36-3.78) |

| Neoplasm | 1508 (5.2) | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) | -† |

| Blood and blood-forming organs | 1110 (3.8) | 1.04 (0.83-1.30) | -† |

| Genitourinary system | 1107 (3.8) | 0.92 (0.77-1.09) | 0.42 (0.25-0.72)† |

| Symptoms/Signs | 1002 (3.4) | 0.93 (0.78-1.12) | 0.06 (0.01-0.43)† |

| Musculoskeletal system | 851 (2.9) | 1.32 (1.12-1.56) | 1.98 (1.33-2.95) |

| Congenital anomalies | 832 (2.9) | 0.64 (0.52-0.79) | 0.20 (0.05-0.76)† |

| Skin/Subcutaneous tissue | 731 (2.5) | 1.30 (1.09-1.55) | 0.70 (0.33-1.49)† |

Compared with Non-Ob reference population, from models adjusted for sex, age, and fiscal year, and accounting for multiple inpatient discharges per unique individual.

Estimates may be unstable: on the basis of <10 inpatient discharges for Ob/Dx group (-indicates not estimable).

Because mental health diagnoses represented the largest category of discharges, we also examined the odds of specific categories of mental health care. The Ob/Dx group had significantly higher odds of a primary diagnosis of affective disorders (AOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.31-2.11) and schizophrenia (AOR, 4.19; 95% CI, 2.65-6.60) compared with Non-Ob discharges. The Ob/No Dx group experienced higher odds of affective disorders (AOR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.31) and anxiety disorders (AOR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.10-1.53) than Non-Ob discharges. Other primary diagnoses were not different from the Non-Ob group.

DISCUSSION

This report critically analyzed and characterized inpatient pediatric populations by existence of measured obesity using BMI compared with diagnosed obesity using ICD-9 codes. We report that an inpatient diagnosis of obesity severely underestimates the healthcare utilization and misrep-resents the disease-specific utilization of patients with measured obesity (eg, BMI ≥95th percentile). Our estimate of 1.7% of inpatient stays with any discharge diagnosis of obesity is consistent with earlier studies based on administrative data.4,9 However, 20.4% of pediatric inpatient stays at our institution were associated with measured obesity, a >10-fold higher prevalence. Our prevalence of inpatient obesity is consistent with measured obesity rates reported in pediatric out-patient treatment settings (20.2%-21.9%),10,11 but higher than an Australian pediatric inpatient study (11%).12 Thus, only 8% of the obese inpatients in this study were associated with any diagnosis of obesity, highlighting the very infrequent inpatient use of obesity diagnoses, and low sensitivity of obesity diagnosis for identifying children with obesity. Indeed, obese inpatients with an obesity diagnosis were the distinct minority in this study. This suggests that research with a diagnosis of obesity using ICD-9 codes to identify obese inpatients may significantly underestimate the magnitude of utilization and economic impact of inpatients with BMI ≥95th percentile.

This study also demonstrates utilization differences between cohorts of inpatients with a diagnosis of obesity and patients identified as obese with measured BMI. The average length of stay associated with measured (but not diagnosed) obesity (Ob/No Dx) was longer than the non-obese reference, without an increase in discharges per unique individual, suggesting that pediatric obesity may increase general complexity or severity of inpatient care. By contrast, obese patients with a diagnosis of obesity (Ob/Dx) have significantly shorter lengths of stay and fewer hospital discharges per person than the non-obese inpatient population. Thus, the diagnosis of pediatric inpatient obesity is more likely to identify sporadic, potentially non-representative, hospital discharges with shorter lengths of stay.

In addition, we report that analyzing only those hospital discharges with a diagnosis of obesity (Ob/Dx) would result in an overestimation of the risk of mental health, endocrine, and musculoskeletal primary diagnoses and an underestimate of risk of most other diagnosis categories. In particular, our data suggest that concern about excessive inpatient endocrine consequences of pediatric obesity may be exaggerated. In contrast to earlier studies,4,13 we report that Ob/No Dx is actually associated with lower odds of endocrine disorders compared with a non-obese inpatient population. Therefore extreme caution should be exercised when using administrative datasets to characterize disease-specific inpatient utilization in obese pediatric populations.

The predominance of behavioral and psychosocial diagnoses in obese children highlights an important area of concern. Obese inpatients in this study were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of mental health problems than non-obese inpatients, particularly for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Whether this reflects psychiatric issues deriving from patients’ obesity status14,15 or weight gain in response to psychiatric medications16 is unclear. Our data are consistent with nationally representative data indicating that pediatric patients with a secondary diagnosis of obesity were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of affective disorder9 or various conduct disorders.4 Another study reported higher Medicaid mental health expenditures for overweight than normal-weight adolescents, despite similar utilization of mental health services.13 Further research may be needed to identify specific mental health needs of obese pediatric inpatients.

The strengths of this study include a large, current, regionally representative view of pediatric inpatient care with measured BMI. In addition, our analysis controlled for multiple admissions from the same unique individual, reducing the impact of highly influential individuals with multiple discharges. Such analysis is not possible with large administrative datasets, but results in a more accurate estimate of the effects of BMI on inpatient utilization. Some limitations should also be acknowledged. It is possible that using clinical data may result in inaccuracies in calculating BMI. We inspected records of all obese individuals with at least 2 hospital discharges to compare BMI percentiles and found no instances of outlier BMIs that would have resulted in misclassification. We also examined all records for the Dx/Non-Ob group. Most of these discharges were for overweight individuals (eg, BMI 85th-95th percentile), suggesting potential misclassification by clinicians rather than significant errors in measurement. BMI values out of range of biologic plausibility were also excluded without a compelling reason to retain them (eg, plausible height plus an obesity diagnosis or known patient in bariatric clinic). Thus, we feel confident that the BMI values in this analysis are valid.

Using inpatient diagnoses of obesity in children greatly underestimates the total health care utilization by obese children and misidentifies patterns of specific inpatient care in this population. In light of the growing childhood obesity epidemic in the United States, these findings should be taken into account when interpreting data derived from diagnosis-based identification of obese inpatients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the authors’ divisions at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- CCHMC

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

- CCS

Clinical Classification System

- Dx/Non-Ob

Diagnosed obesity without obesity

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- Non-Ob

Neither measured nor diagnosed obesity

- Ob/Dx

Obesity with an obesity diagnosis

- Ob/No Dx

Obesity without an obesity diagnosis

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heithoff KA, Cuffel BJ, Kennedy S, Peters J. The association between body mass and health care expenditures. Clin Ther. 1997;19:811–20. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quesenberry CP, Jr, Caan B, Jacobson A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:466–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G, Dietz WH. Economic burden of obesity in youths aged 6 to 17 years: 1979-1999. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e81. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Dec 3, 2002];A SAS program for the CDC Growth Charts. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/sas.htm.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Jan 13, 2007];Cut-offs to define outliers in the 2000 CDC Growth Charts. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/00binaries/BIV-cutoffs.pdf.

- 7.Institute of Medicine [Jul 26, 2007];Expert Committee Recommendations on the Assessment, Prevention and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/ped_obesity_recs.pdf.

- 8.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) [May 5, 2007];Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. 2007 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 9.Woolford SJ, Gebremariam A, Clark SJ, Davis MM. Incremental hospital charges associated with obesity as a secondary diagnosis in children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1895–901. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampl SE, Carroll CA, Simon SD, Sharma V. Resource utilization and expenditures for overweight and obese children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:11–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorsey KB, Wells C, Krumholz HM, Concato JC. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of childhood obesity in pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:632–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor J, Youde LS, Allen JR, Baur LA. Obesity and under-nutrition in a tertiary paediatric hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buescher PA, Whitmire JT, Plescia M. Relationship between body mass index and medical care expenditures for North Carolina adolescents enrolled in Medicaid in 2004. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janicke DM, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ, Zhang J. Psychiatric diagnosis in children and adolescents with obesity-related health conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:276–84. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817102f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janicke DM, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ, Zhang J. The association of psychiatric diagnoses, health service use, and expenditures in children with obesity-related health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 Jun 3; doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn051. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel NC, Hariparsad M, Matias-Akthar M, Sorter MT, Barzman DH, Morrison JA, et al. Body mass indexes and lipid profiles in hospitalized children and adolescents exposed to atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:303–11. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]