Abstract

Objective:

We undertook a population-based, case-control study to examine a dose-response relationship between alcohol intake and risk of ischemic stroke in Koreans who had different alcoholic beverage type preferences than Western populations and to examine the effect modifications by sex and ischemic stroke subtypes.

Methods:

Cases (n = 1,848) were recruited from patients aged 20 years or older with first-ever ischemic stroke. Stroke-free controls (n = 3,589) were from the fourth and fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and were matched to the cases by age (±3 years), sex, and education level. All participants completed an interview using a structured questionnaire about alcohol intake.

Results:

Light to moderate alcohol intake, 3 or 4 drinks (1 drink = 10 g ethanol) per day, was significantly associated with a lower odds of ischemic stroke after adjusting for potential confounders (no drinks: reference; <1 drink: odds ratio 0.38, 95% confidence interval 0.32–0.45; 1–2 drinks: 0.45, 0.36–0.57; and 3–4 drinks: 0.54, 0.39–0.74). The threshold of alcohol effect in women was slightly lower than that in men (up to 1–2 drinks in women vs up to 3–4 drinks in men), but this difference was not statistically significant. There was no statistical interaction between alcohol intake and the subtypes of ischemic stroke (p = 0.50). The most frequently used alcoholic beverage was one native to Korea, soju (78% of the cases), a distilled beverage with 20% ethanol by volume.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that light to moderate distilled alcohol consumption may reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in Koreans.

Previous studies, including recent meta-analyses, have consistently reported that heavy alcohol intake increases the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.1,2 However, the effect of light to moderate drinking remains controversial and is less clearly defined.3–8 These controversies may be attributed to heterogeneity of stroke subtypes, potential differential effects across sex and race/ethnic groups, and different beverage types and amounts of alcohol consumed.9

A J-shaped relationship between ischemic stroke and alcohol consumption was reported in Western countries, especially in Caucasians, but this relationship was shown to be inconclusive in Asians.10,11 Regarding beverage types, it was suggested that wine drinkers might have a lower stroke risk than do beer or liquor drinkers.6,12 Types of alcoholic beverages and amounts of alcohol consumed may be different among races and between men and women.13

To overcome the aforementioned limitations of previous studies in relation to Asian populations, we performed a case-control study based on a prospective multicenter stroke registry (Clinical Research Center for Stroke [CRCS]) database14 and a nationally representative health survey (Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [KNHANES]) database.15

By using these large databases, we aimed to estimate thresholds of alcohol dose that may be protective or harmful for ischemic stroke and examine the effect modifications by sex and ischemic stroke subtypes in a Korean population.

METHODS

Nine CRCS-affiliated hospitals in South Korea (from 7 cities: Seoul, Seongnam, Ilsan, Daejeon, Daegu, Gwangju, and Busan) participated in this population-based, case-control study. The fifth section of the CRCS project (CRCS-5) is dedicated to epidemiologic studies for characterizing the epidemiology of stroke and the status of stroke care in Korea.16 In April 2008, 9 centers of CRCS-5, including both university hospitals and regional centers, began to construct a Web-based, prospective registry for acute stroke and the number of participating centers increased to 15 in 2014. Registered patients could be assumed to come from a representative sample of the entire stroke population since the distribution of age and sex in the CRCS-5 registry database was almost identical to that of a report from the National Health Insurance Review Board in Korea, which was published elsewhere.16

During a similar period, the fourth (2007–2009) and fifth (2010–2012) KNHANES was conducted by the Korean Center for Disease Control to investigate the health status of the Korean population through a multistage clustered probability sampling; the target population comprises noninstitutionalized Korean citizens residing in Korea.15 We developed a case-control study about alcohol intake as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Case patients came from the CRCS-5 registry database and control subjects were selected from the fourth and fifth KNHANES database.

Selection of cases and controls, standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Cases were recruited from patients admitted to study hospitals for first-ever ischemic stroke between January 2011 and February 2013. Diffusion-weighted MRI in each patient confirmed the presence of acute infarction. If patients had altered consciousness or severe aphasia due to acute stroke, we interviewed family members or persons who lived with the patient and were knowledgeable about the patient's medical history and drinking habit. Patients who could not be interviewed and did not have a proper informant were excluded. All cases had given informed consent to participate in this study, and the local institutional review boards of the participating centers approved the study protocol. Controls were selected among those who were recruited to the KNHANES between 2007 and 2012. Cases and controls that were younger than 20 years and had history of stroke were excluded from the study. One case patient was matched to 2 control subjects for age (±3 years), sex, and education years (0–6 years vs >6 years).

Alcohol consumption assessment.

All participants including cases and controls completed an interview using the same structured questionnaire about alcohol intake. To estimate alcohol exposure, we questioned all cases and controls about the frequency of drinking, amount of alcohol consumed on each occasion, and the preferred type of alcoholic beverage during the past 12 months. The frequency of drinking was classified into 5 categories: 4 times or more a week, 2–3 times a week, 2–4 times a month, once a month, and less than once a month. The amount of alcohol intake and the type of alcoholic beverage in each occasion were recorded. Daily amount of alcohol intake was calculated according to the following formula: 1 drink = 10 g ethanol, regardless of beverage type.

For Koreans, 2 native, popular alcoholic beverages are soju and makkoli. Soju is a distilled alcoholic beverage that contains 20% alcohol by volume. A glass of soju was 60 mL and a bottle of soju was 360 mL by container volume. The amount of pure alcohol was 9.6 g in a glass of soju using specific gravity of 0.8 to estimate the grams of ethanol. Makkoli is an unfiltered alcoholic beverage with 6% alcohol by volume.

Risk factors and adjustment.

Risk factors were chosen for adjustment based on their relative importance in the primary prevention guidelines17 and the comparability of their definitions between the CRCS-5 and KNHANES. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking, coronary artery disease, and obesity were selected risk factors, and the definition of each has been described in our previous study.16 Despite its importance as a stroke risk factor, atrial fibrillation was not included because the KNHANES did not gather this information. For cases, smoking was defined as a current smoker who had smoked at least one or more cigarettes in the last month, whereas for controls, a current smoker was defined as a person with a lifetime history of smoking ≥100 cigarettes and who smoked almost every day or occasionally. Body mass index was calculated from height and weight measured or self-reported. Education level was expressed as years of education completed.

Statistical analysis.

Risk factors based on a prior study reporting a minimum odds ratio (OR) for ischemic stroke at 1 to 2 drinks,5 a total of 1,200 cases and 2,400 controls was estimated to be needed to ensure a 90% of power of detecting an OR of 0.51 with a 2-tailed 5% level of significance and a ratio of controls to cases of 2 to 1. To ensure a sufficient number of control subjects to identify a dose-response relationship and to determine a threshold dose that may be protective for stroke, we extended control enrollment from 2012 (the latest year when the information about alcohol intake was available in the KNHANES database) to 2007.

Average daily alcohol consumption during the past 12 months was used as a main exposure variable. It was divided into 6 categories: (1) reference: no drink during the past 12 months; (2) light: less than 1 drink per day; (3) light to moderate: 1–2 drinks per day; (4) moderate: 3–4 drinks per day; and (5) heavy: 5 or more drinks per day.5

A conditional logistic regression model was applied to this case-control study matched for age, sex, and education level, and adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for the frequency of alcohol consumption, the amount of alcohol consumed each time, and the average daily alcohol consumption (drinks). Those who had abstained from drinking during the past 12 months were used as a reference group.

To examine a nonlinear association between an amount of alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke, a χ2 test for trend for a quadratic effect was performed.

Analyses were performed for all participants as well as for men and women, separately. Adjustments were made for conventional stroke risk factors such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, body mass index, and current smoking. We examined whether the threshold dose may differ by subtype of ischemic stroke. Three subtypes, large artery atherosclerosis, small vessel occlusion, and cardioembolism, were chosen for the analysis based on the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification with some modifications.18

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC), and statistical significance was declared when a 2-tailed p value was <0.05.

RESULTS

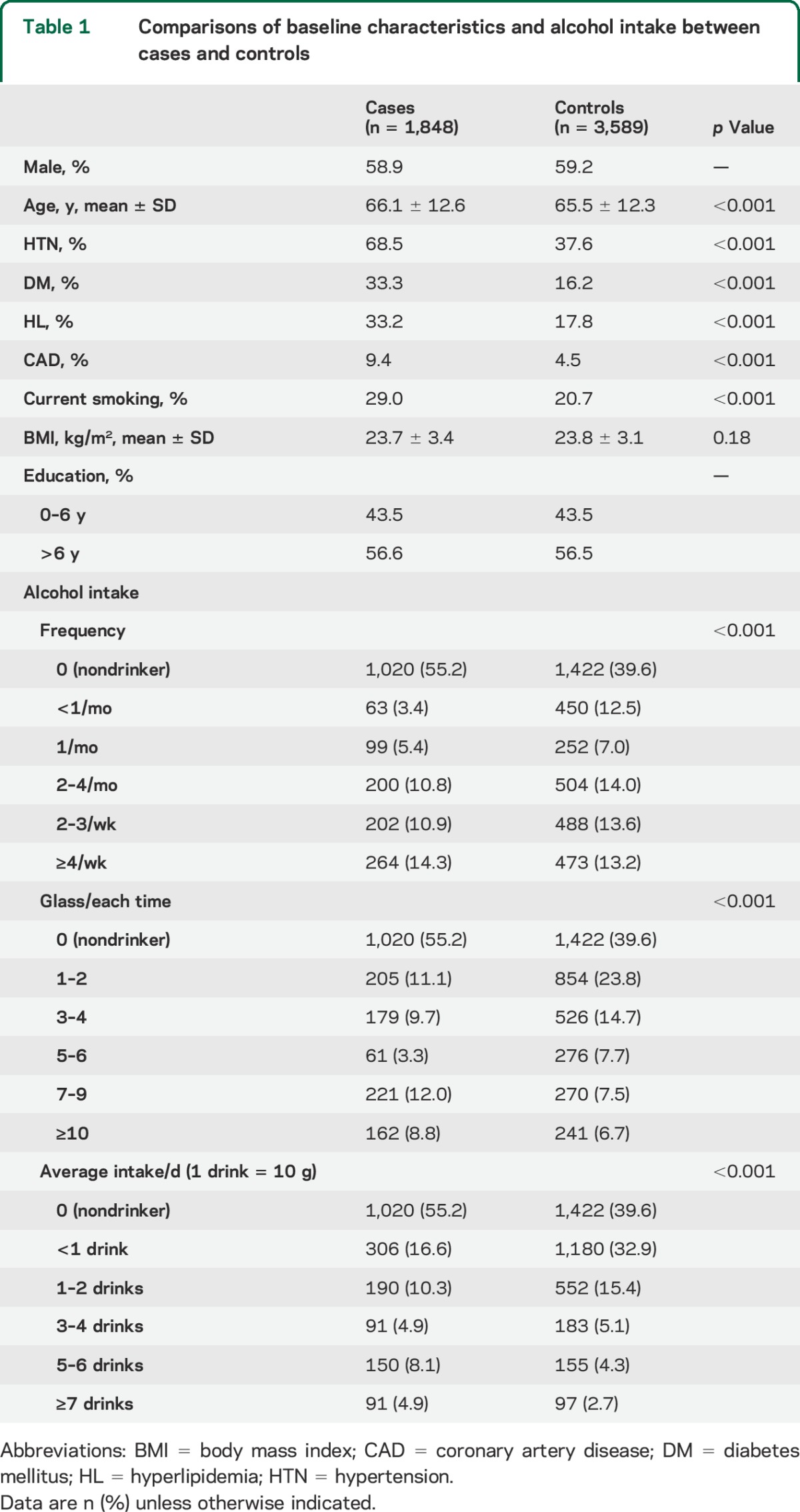

During 25 months, 1,848 cases (mean age, 66.1 years; men, 58.9%) were enrolled and matched to 3,589 controls (figure 1). Among the 1,848 cases, 1,295 patients (70.1%) and 553 other informants (29.9%) completed the questionnaire about alcohol intake. The cases had a higher frequency of stroke risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and current smoking) than controls (table 1). The mean age of the cases was slightly higher than that of the controls (66.1 vs 65.5 years).

Figure 1. Flowchart of enrollment of study participants.

*Matching of controls to case for age (±3 years), sex, and years of education (0–6 years vs >6 years). Cases (n = 107) were matched to one control subject (1:1). BMI = body mass index.

Table 1.

Comparisons of baseline characteristics and alcohol intake between cases and controls

Nondrinkers were more common in the case group than in the control group (55.2% vs 39.6%), but cases, if they drank, did so more frequently and in larger amounts. Average alcohol consumption was higher in cases than controls. In the cases, about a third of drinkers had less than 1 drink per day and 40% of drinkers had 3 drinks or more per day, but in the controls, more than half of drinkers had less than 1 drink per day and only 20% of drinkers had 3 or more drinks per day.

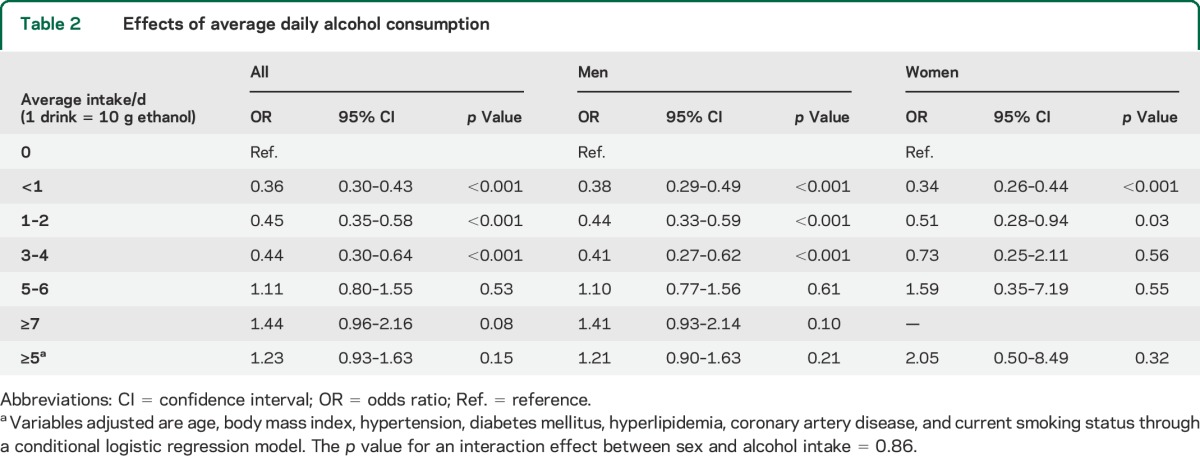

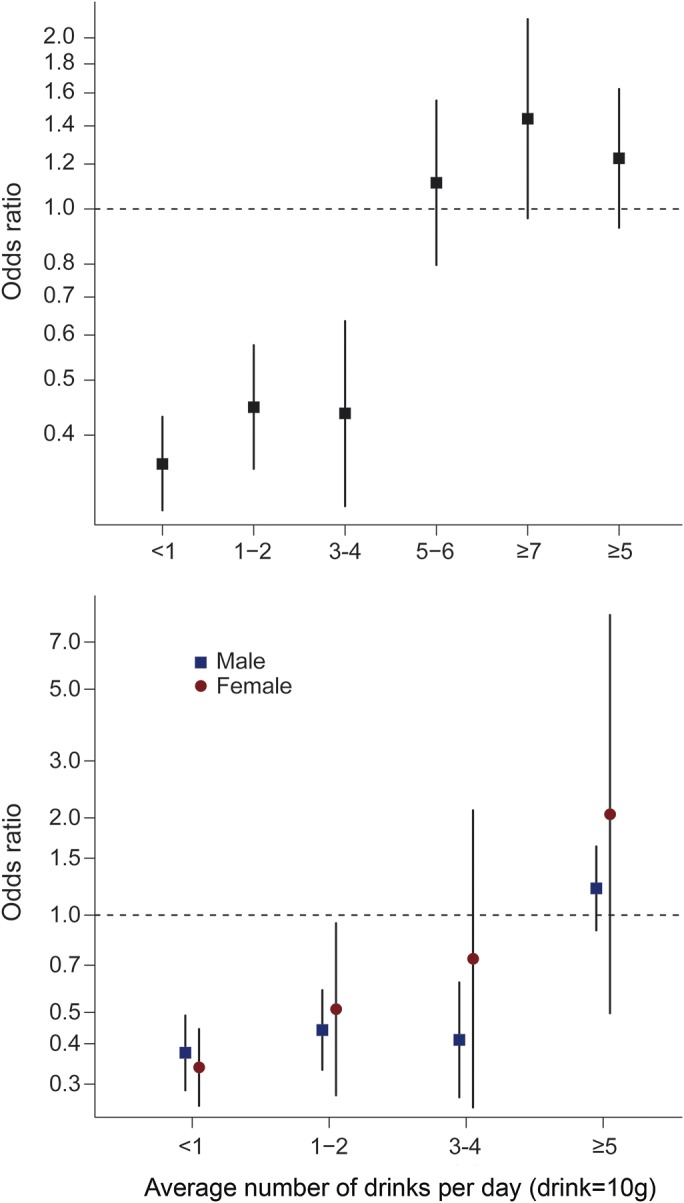

The effect of lowering the odds of ischemic stroke by alcohol intake was observed up to 3–4 drinks (1 drink = 10 g ethanol) per day independent of traditional stroke risk factors (table 2 and figure 2). The adjusted ORs (95% CIs) were 0.36 (0.30–0.43) for <1 drink, 0.45 (0.35–0.58) for 1–2 drinks, 0.44 (0.30–0.64) for 3–4 drinks, and 1.23 (0.93–1.63) for ≥5 drinks compared with nondrinkers.

Table 2.

Effects of average daily alcohol consumption

Figure 2. Relationship between alcohol intake and ischemic stroke in a logit scale.

In men, the effect by alcohol intake persisted up through 3–4 drinks per day, whereas in women, it persisted up through 1–2 drinks per day (table 2 and figure 2). However, the interaction between sex and alcohol intake was not statistically significant (p = 0.86). Graphic analysis for dose-response relationships between average alcohol intake and ischemic stroke reveals an overt threshold effect with narrow CIs for all subjects and men and a weak effect with wide CIs for women (figure 2). A nonlinear association between alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke was observed for all (p for a quadratic effect <0.0001), for men (p < 0.0001), and for women (p = 0.0050).

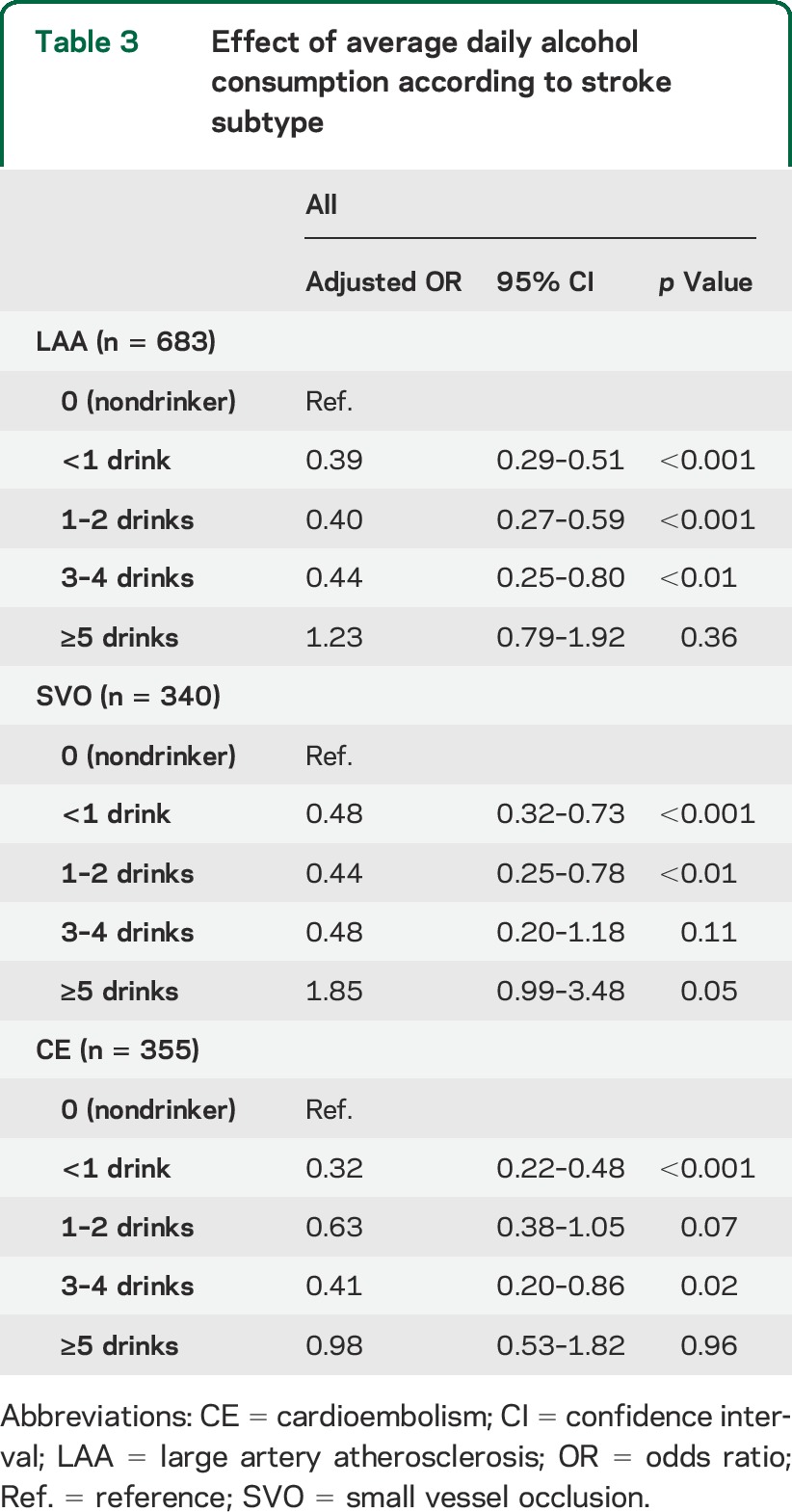

The effect of lowering the odds of ischemic stroke by alcohol intake did not seem to be different among the 3 subtypes of ischemic stroke (table 3), and there was no statistical interaction between alcohol intake and stroke subtype (p = 0.50). Beverage type in the case group of drinkers is presented in table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org. Information on preferred alcoholic beverage was not available from the KNHANES database, and consequently in the controls. The most popular beverage type in the cases was soju (78.1%), a distilled alcoholic beverage with 20% ethanol by volume and similar to liquor, followed by makkoli (9.5%), an unfiltered wine made of rice or wheat with 6% ethanol by volume. Both beverages are native to Korea. Only 1.3% favored wine.

Table 3.

Effect of average daily alcohol consumption according to stroke subtype

As a post hoc analysis, the effect of drinking pattern according to average alcohol consumption was examined. Drinking pattern was dichotomized into regular (4 times per week or more) and irregular (less than 4 times per week) among those drinking less than 5 times per week. In light or light to moderate drinkers, both regular and irregular drinking lowered the odds of ischemic stroke significantly, while in moderate drinkers with 3–4 drinks per day, regular drinking showed an adjusted OR (95% CI) of 0.20 (0.10–0.38) but irregular drinking did not lower the odds (OR 0.77 [95% CI 0.53–1.12]).

DISCUSSION

We found that alcohol intake of 3 or 4 drinks per day decreased the odds of ischemic stroke compared to no drinking, independent of conventional stroke risk factors. Heavy drinking (≥5 drinks per day) tended to increase the odds, although the trend was not statistically significant mainly because of a small number of heavy drinkers in the study population. The results suggested a nonlinear association between alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study reported a similar J-shaped association in a multiethnic population, and there was no significant interaction between race/ethnicity and alcohol consumption.9

However, in large cohort studies in China and Japan, light drinking was associated with slightly lower stroke risk that did not reach statistical significance in the subgroup with ischemic stroke.19–21 The inconclusive results may be attributable to inaccurate diagnosis of stroke types (ischemia vs hemorrhage). Imaging such as CT or MRI could not be performed in all participants. To avoid this limitation, we adopted a case-control study design and prospectively enrolled a large number of patients with infarction confirmed by diffusion-weighted imaging.

The type of alcoholic beverage may be a confounder. The components of wine, in addition to ethanol, are presumed to be responsible for the protective effect on risk of stroke.6,12,22 However, this possible differential effect among the different types of alcoholic beverages was not confirmed in a multiethnic population.5 In our study, Koreans favored drinking soju and makkoli, beverages native to Korea.23 Soju is highly distilled ethanol made from sweet potatoes and tapioca, mixed with water, flavoring, and sweetener. It does not contain any other component, such as resveratrol or other antioxidants, that would have positive health effects. Makkoli is traditionally made from rice, although variations are made from wheat, and some brands are flavored with corn, chestnut, apple, or other produce. Its potential health effects have not been well studied. Japanese have an alcoholic beverage type similar to that used in Korean. In a middle-aged cohort of Japanese men, drinking up to 2 drinks per day was associated with a reduced risk of ischemic stroke.24 Our results suggest that alcohol types other than wine could have protective effects on the risk of ischemic stroke in light to moderate drinkers.

Sex may also be a confounder in the relationship of alcohol consumption and stroke. Women are more likely to die at moderate to high levels of alcohol consumption, probably because of an increased risk of cancer.25 Furthermore, women have lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity than men, resulting in higher blood ethanol levels.26

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline recommends alcohol intake of no more than 2 drinks per day in men and no more than 1 drink per day in nonpregnant women.17 Our study shows a dose-response curve similar for both women and men when alcohol intake is light, but the curves differ with heavier alcohol intake. Furthermore, the effect of lowering the odds of ischemic stroke by alcohol intake disappears at lower doses in women than in men. In our study, although the interaction between sex and alcohol intake was not statistically significant, the threshold of alcohol intake differed by sex for risk of ischemic stroke.

Our results show that the effect of light to moderate drinking was consistently observed regardless of ischemic stroke subtype (table 3). However, prior studies have shown inconsistencies. The protective effect of moderate alcohol intake was not different between superficial and deep cerebral infarctions in a case-control study from Spain.27 In the Northern Manhattan Study, reduction of risk was not evident for atherosclerotic stroke but was for nonatherosclerotic stroke.28 In Japanese middle-aged men, a lower risk of ischemic stroke, more specifically lacunar infarcts, was observed among light to moderate drinkers.24 These inconsistent findings may be attributable to a limited number of patients according to ischemic stroke subtype, weakening possible associations in underpowered studies. Applying different criteria for subtype classification could be another explanation. A further confirmative study with a sufficient sample size is warranted.

This study has several limitations. Cohort studies provide stronger evidence about strength of association between an exposure of interest and a disease. Case-control studies are usually less robust at showing an association, as they are more prone to bias than cohort studies. In our study, a large proportion of patients with severe stroke and aphasia were excluded because of lack of information on alcohol intake. However, if a well-informed family member or other informant could provide valid information, the patient was enrolled.

We matched controls to cases by age, sex, and education level. Some of the oldest cases (>80 years) were not successfully matched; therefore, cases who were too old to match were excluded from the study. A relatively small number of heavy alcohol consumers (≥7 drinks per day, less than 5%) were enrolled in this study. Therefore, we were not able to find an association with stroke when there was high alcohol consumption. The issue of binge drinking was not addressed in our study.23

We also explored the relationship between regular, more moderate daily alcohol consumption and heavier drinking during a circumscribed period (e.g., weekends) because drinking patterns may differ among individuals with the same average weekly alcohol consumption. From a physiologic perspective, one might expect a lower risk of stroke associated with regular daily light or moderate intake than with binge drinking.29 Our post hoc analysis showed that in moderate drinkers who had an average of 3 or 4 drinks per day, the beneficial association of alcohol intake on ischemic stroke disappeared if the drinking pattern was irregular, whereas at lower or more modest alcohol consumption levels, whether regular or irregular, there was a lower risk.

We defined nondrinker status during the past 12 months as the reference drinking level. It has been suggested that combining lifetime abstainers with former heavy drinkers who became abstinent for health reasons might bias the results of protection conferred by abstinence.

Finally, it should be noted that there were some discrepancies in definitions of certain risk factors for adjustment between cases and controls. Especially for smoking, the discrepancy might lead to overestimation of the prevalence of current smoking in controls, followed by weakening of the strength of association between smoking and ischemic stroke, and eventually inadequate adjustment as a confounder if we assume the significant dose-dependent relationship between alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking.8

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that light to moderate alcohol intake may be associated with a reduced risk of ischemic stroke in a Korean population with a different favored type of alcoholic beverage than in most countries.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- CI

confidence interval

- CRCS

Clinical Research Center for Stroke

- KNHANES

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Soo Joo Lee: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, statistical analysis. Yong-Jin Cho: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision. Jae Guk Kim: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Youngchai Ko: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Keun-Sik Hong: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Jong-Moo Park: study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data, study supervision. Kyusik Kang: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Tai Hwan Park: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Sang-Soon Park: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Kyung Bok Lee: study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Jae Kwan Cha: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Dae-Hyun Kim: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Jun Lee: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data. Joon-Tae Kim: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Juneyoung Lee: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, statistical analysis. Ji Sung Lee: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, statistical analysis. Myung Suk Jang: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Moon-Ku Han: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Philip B. Gorelick: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Hee-Joon Bae: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision, obtaining funding.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

DISCLOSURE

S. Lee, Y. Cho, J.G. Kim, Y. Ko, K. Hong, J. Park, K. Kang, T. Park, S. Park, K. Lee, J. Cha, D. Kim, Jun Lee, J.-T. Kim, Juneyoung Lee, J.S. Lee, M. Jang, M. Han, and P. Gorelick report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. H. Bae is the principal investigator, a member of steering committee, and/or a site investigator of multicenter clinical trials or clinical studies sponsored by Otsuka Korea, Bayer Korea, Handok Pharmaceutical Company, SK Chemicals, ESAI-Korea, Daewoong Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis Korea, AstraZeneca Korea, Dong-A Pharmaceutical, and Yuhan Corporation; served as the consultant or on the scientific advisory board for Bayer Korea, Boehringer Ingelheim Korea, BMS Korea, and Pfizer Korea; and received lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca Korea, Bayer Korea, BMS Korea, Covidien Korea, Novartis Korea, Otsuka Korea, Pfizer Korea, and Daiichi Sankyo Korea (modest). Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reynolds K, Lewis B, Nolen JD, Kinney GL, Sathya B, He J. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2003;289:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2010;10:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill JS, Shipley MJ, Tsementzis SA, et al. Alcohol consumption: a risk factor for hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Med 1991;90:489–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamrozik K, Broadhurst RJ, Anderson CS, Stewart-Wynne EG. The role of lifestyle factors in the etiology of stroke: a population-based case-control study in Perth, Western Australia. Stroke 1994;25:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacco RL, Elkind M, Boden-Albala B, et al. The protective effect of moderate alcohol consumption on ischemic stroke. JAMA 1999;281:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malarcher AM, Giles WH, Croft JB, et al. Alcohol intake, type of beverage, and the risk of cerebral infarction in young women. Stroke 2001;32:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donahue RP, Abbott RD, Reed DM, Yano K. Alcohol and hemorrhagic stroke. The Honolulu Heart Program. JAMA 1986;255:2311–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorelick PB, Rodin MB, Langenberg P, Hier DB, Costigan J. Weekly alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and the risk of ischemic stroke: results of a case-control study at three urban medical centers in Chicago, Illinois. Neurology 1989;39:339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacco RL. Alcohol and stroke risk: an elusive dose-response relationship. Ann Neurol 2007;62:551–552. Letter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzaglia G, Britton AR, Altmann DR, Chenet L. Exploring the relationship between alcohol consumption and non-fatal or fatal stroke: a systematic review. Addiction 2001;96:1743–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camargo CA., Jr Moderate alcohol consumption and stroke: the epidemiologic evidence. Stroke 1989;20:1611–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truelsen T, Grønbaek M, Schnohr P, Boysen G. Intake of beer, wine, and spirits and risk of stroke: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Stroke 1998;29:2467–2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klatsky AL, Siegelaub AB, Landy C, Friedman GD. Racial patterns of alcoholic beverage use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1983;7:372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim BJ, Han MK, Park TH, et al. Current status of acute stroke management in Korea: a report on a multicenter, comprehensive acute stroke registry. Int J Stroke 2014;9:514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park TH, Ko Y, Lee SJ, et al. Gender differences in the age-stratified prevalence of risk factors in Korean ischemic stroke patients: a nationwide stroke registry-based cross-sectional study. Int J Stroke 2014;9:759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:517–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko Y, Lee S, Chung JW, et al. MRI-based algorithm for acute ischemic stroke subtype classification. J Stroke 2014;16:161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazzano LA, Gu D, Reynolds K, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk for stroke among Chinese men. Ann Neurol 2007;62:569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikehara S, Iso H, Yamagishi K, Yamamoto S, Inoue M, Tsugane S; JPHC Study Group. Alcohol consumption, social support, and risk of stroke and coronary heart disease among Japanese men: the JPHC Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:1025–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikehara S, Iso H, Yamagishi K, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke and coronary heart disease among Japanese women: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Prev Med 2013;57:505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Djoussé L, Ellison RC, Beiser A, Scaramucci A, D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA. Alcohol consumption and risk of ischemic stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 2002;33:907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sull JW, Yi SW, Nam CM, Ohrr H. Binge drinking and mortality from all causes and cerebrovascular diseases in Korean men and women: a Kangwha cohort study. Stroke 2009;40:2953–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iso H, Baba S, Mannami T, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among middle-aged men: the JPHC Study Cohort I. Stroke 2004;35:1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004;38:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely M, Hardy R, Longford NT, Wadsworth ME. Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol consumption and drink problems are largely accounted for by body water. Alcohol Alcohol 1999;34:894–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caicoya M, Rodriguez T, Corrales C, Cuello R, Lasheras C. Alcohol and stroke: a community case-control study in Asturias, Spain. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkind MS, Sciacca R, Boden-Albala B, Rundek T, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Moderate alcohol consumption reduces risk of ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 2006;37:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palomäki H, Kaste M. Regular light-to-moderate intake of alcohol and the risk of ischemic stroke: is there a beneficial effect? Stroke 1993;24:1828–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.