Abstract

Corneal injury can produce an aversive sensitivity to light, photophobia. Using topical application of lidocaine, a local anesthetic, and tetrodotoxin (TTX), a selective voltage-sensitive sodium channel blocker, we assessed whether enhanced aversiveness to light induced by corneal injury was due to the enhanced activity in corneal afferents. Eye closure induced by 30 s exposure to bright light (460–485 nm) was increased 24 h after corneal injury induced by de-epithelialization. While the topical application of lidocaine did not affect the baseline eye closure response to bright light in control rats, it eliminated the enhancement of the response to the light stimulus following corneal injury (photophobia). Similarly, topical application of TTX had no effect on the eye closure response to bright light in rats with intact corneas, but markedly attenuated photophobia in rats with corneal injury. Given the well-established corneal toxicity of local anesthetics, we suggest TTX as a therapeutic option to treat photophobia, and possibly other symptoms that occur in clinical diseases that involve corneal nociceptor sensitization.

Keywords: Eye pain, photophobia, tetrodotoxin, lidocaine, corneal nociceptor

Introduction

Photophobia, an aversive sensation induced by bright visual stimuli 26, is markedly enhanced in many patients that experience corneal injury, such as occurs following corneal refractive surgery 4, corneal abrasion 32, chemical injury 13, Dry Eye Syndrome (DES) 33 or in long-term contact lens wearers 29. While even bright light does not activate corneal afferents, it does excite photosensitive melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells that activate neurons in the superficial laminae of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Vc/C1) (possibly by increasing ocular blood flow 26), a site in the central nervous system that is involved in transmitting pain signals. The melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells also project to the thalamic relay nuclei that also receive nociceptive inputs 19, 24. Since the cornea is innervated by nociceptors that encode mechanical, thermal and chemical stimuli 1, which also project to Vc/C1 14, 27, as well as to the rostral ventrolateral pole of the trigeminal interpolaris/caudalis, the convergence could occur proximally either in the trigeminal nuclear complex and/or at higher levels (e.g. in thalamic relay nuclei).

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) inhibits a subset of voltage-gated sodium channels that play a key role in inflammatory and neuropathic pain, in particular Na(V) 1.7 9, which is inhibited by an extremely low, sub-nanomolar concentration of TTX 16. Of note, we have observed that TTX can reverse mechanical hyperalgesia in sensitized muscle nociceptors without eliminating protective nociceptive behaviors (P. Alvarez, unpublished observations). This is important with respect to treatment of corneal symptoms, as elimination of protective nociceptive reflexes (e.g. eyelid closure) in response to noxious stimulation of the corneal surface, allows continued corneal injury. Chronic use of local anesthetics to treat ocular pain is contraindicated due to major dose- and time-dependent corneal toxicity 11, 28. Since TTX has a much lower corneal toxicity, it might be useful for symptoms that are dependent on enhanced input from nociceptive corneal afferents 36. Therefore, in the present study we evaluated if topical application of TTX attenuates photophobia in the setting of nociceptor sensitization induced by traumatic injury to the cornea.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on adult male Sprague Dawley rats, (200–250 g; Charles River, Hollister, CA). Animals were housed 3 per cage, under a 12 h light/dark cycle, in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment. Food and water were available ad libitum. All behavioral testing was performed between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM. Rats were acclimatized to the testing environment, by bringing them to the experimental environment, in their home cages, where they were left for 30–60 min, after which they were placed in cylindrical clear acrylic restrainers for evaluation of their response to stimulation with a bright light.

All experimental protocols were approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Animal Research and conformed to National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were designed to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Measuring photophobia

Bright light stimulates eye closure even in normal control animals 31, 38. We measured this response to bright light in awake rats after they had been acclimated to being in a restrainer (10 min/day for 3 days). Some rats underwent corneal de-epithelialization injury, as previously described 41. Briefly, in rats anesthetized with 3% isoflurane, a defect in the central part of the cornea in one eye of each rat was made by placing a ~3.5 x 3.5 mm square of filter paper (Whatman Grade 40, GE Health care, Buckinghamshire, UK), saturated with n-heptanol, on the cornea for 90 s. After removing the filter paper, the eye was irrigated with 0.9% saline, and the n-heptanol-treated epithelial surface removed with a sclerotome (Katena Products Inc., Denville, NJ, USA). 24 h after de-epithelialization, the magnitude of eye closure in response to 30-s exposure to high intensity (48 lumens), 460–485 nm wavelength (LXML-PB01-0023 Luxeon® Rebel high power LED) light 26 was again assessed. Of note, the maximal absorbance for melanopsin is ~480 nm 2 and therefore the wavelength of light we used maximally activates the intrinsically photosensitive melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells. Video recordings were made and played back in real-time to grade magnitude of maximal eye closure using the scale illustrated in Figure 1. Bright light induced eye closure was evaluated before and 10 min after topical corneal application of the local anesthetic, lidocaine, or TTX (5 μl volume for each) in awake, lightly restrained rats.

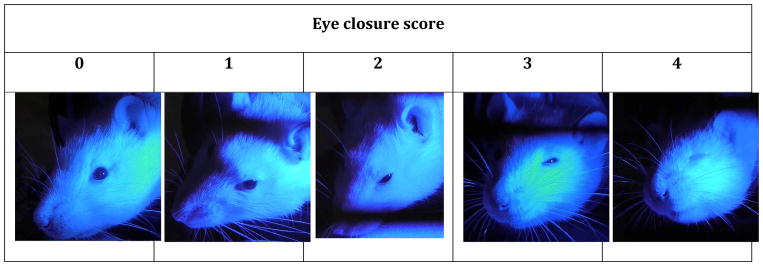

Figure 1. Scale for quantification of eye closure response to bright light in the rat.

Eye closure was scored according to its magnitude: no closure = 0, ~25% closure = 1, ~50% closure = 2, ~75% closure = 3, full closure = 4.

Drugs

Tetrodotoxin citrate (TTX) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), and lidocaine hydrochloride and n-heptanol were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). TTX and lidocaine were dissolved in 0.9% saline. The n-heptanol was used undiluted.

Statistical analyses

Group data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by one- or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

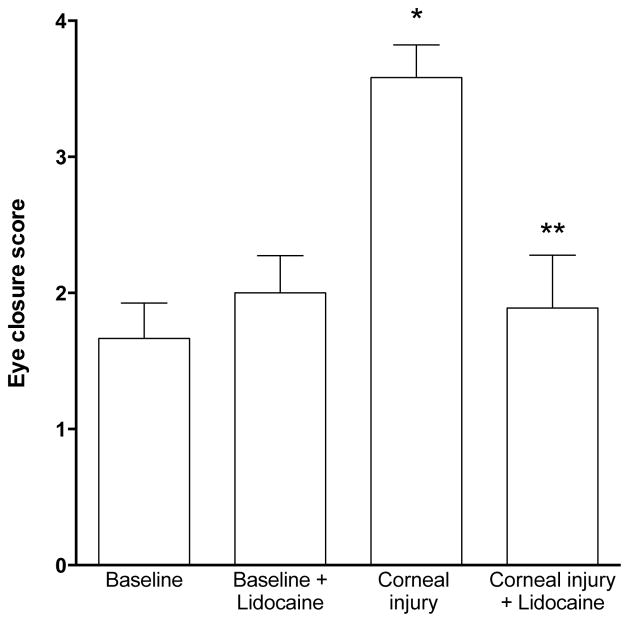

To test the hypothesis that corneal injury enhances aversion to bright light, we compared the eye closure score in response to bright light in control rats and in those that had undergone corneal de-epithelialization injury. Photophobia was significantly increased when measured 24 h following corneal injury (Figure 2). To explore the possibility that enhanced activity in nociceptors, caused by corneal injury, contributes to the enhanced response to bright light (photophobia), we evaluated the effect of the topical application of a local anesthetic to the cornea on injury-induced photophobia. Compatible with the hypothesis that enhanced activity in corneal afferents contributes to the photophobia observed in rats with de-epithelialized corneas, the enhanced closure response in rats with a corneal injury was completely eliminated 10 min after topical application of lidocaine (2%, 10 μl) to the corneal surface (Figure 2, baseline (n=18) vs. corneal injury (n=6) P<0.05; corneal injury (n=6) vs. corneal injury + lidocaine (n=9), P<0.05; baseline (n=18) vs. + lidocaine (n=5), P=N.S., one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test). Thus, our data support the hypothesis that increased activity in corneal nociceptors is responsible for the enhanced aversion to bright light observed in the setting of corneal injury.

Figure 2. Lidocaine attenuates the increase in the eye closure response induced by corneal injury.

Lidocaine (2%, 10 μl) did not significantly affect the magnitude of eye closure produced by exposure to bright light (~48 lumens, 465–480 nm) for 30 s in control eyes. However, the enhanced response, photophobia, following de-epithelialization injury was significantly attenuated by lidocaine (*P<0.05 baseline vs. corneal injury and **P<0.05, corneal injury vs. corneal injury + lidocaine).

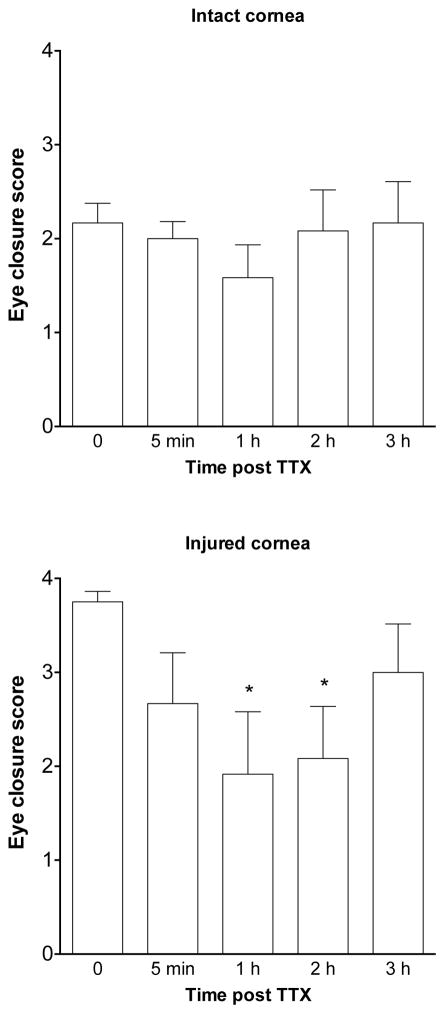

Since repeated use of lidocaine is toxic to corneal stroma 20, we next tested if the enhanced photophobia in the setting of an injured cornea can be attenuated by TTX. Bright light induced eye closure in control rats (intact corneas, n=6) was not affected by application of TTX (1 KM, 10 μl) to the cornea. In contrast, in rats with a corneal injury (n=6), photophobia was significantly attenuated by application of TTX (1 mM, 10 μl) to the corneal surface, when measured 1 and 2 hours after application of TTX (Figure 3, repeated-measures one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post-hoc test). These results suggest that TTX-sensitive sodium channels play an important role in the photophobia observed in the setting of corneal injury.

Figure 3. TTX attenuates photophobia induced by corneal injury.

The magnitude of eye closure response produced by bright light was not significantly affected by TTX (1 mM, 10 μl) applied to rats with uninjured corneas, but was significantly attenuated 1 and 2 h after application TTX to rats with injured corneas (*P<0.001).

Discussion

The topical application of TTX or lidocaine to the cornea similarly attenuated the photophobia induced by corneal injury, while neither TTX nor lidocaine affected the eye closure response to bright light in control rats, in the absence of corneal injury. Of note, the reduction in eye closure in rats with the corneal injury produced by both TTX and lidocaine was to a level similar to that observed in cornea-intact control rats, whose response to bright light was not affected by either TTX or lidocaine, supporting the suggestion that they are eliminating the sensitization state. In addition to eliciting a local inflammatory response, de-epithelialization injures corneal sensory nerve fiber terminals, decreasing neural density in the corneal epithelium within the area of the wound, but doubling it at the wound periphery 7. Thus, abnormal activity in corneal afferents in our model may reflect neuropathic as well as inflammatory mechanisms. Injured afferent sensory fibers have altered expression of membrane ion channels, including the TTX-sensitive Na(V) 1.7 sodium channel 22, 39, which is upregulated by inflammation and nerve injury 17. The altered expression of ion channels in the regenerating nerve terminals is believed to be the origin of the marked increase in spontaneous firing of injured corneal nociceptors 12 and the hyperalgesia that occurs following corneal injury 1. Injury-induced axotomy and sprouting of nerve terminals, and local inflammatory response in the cornea, likely also contribute to the generation of the nerve impulses that contributes to eye pain as well as to photophobia.

Corneal nociceptors stimulate neurons in Vc/C1 superficial laminae of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis 24, 25; and bright light, which activates intrinsically photosensitive melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells, also increases activity of neurons in Vc/C1 and thalamic relay nuclei, enhancing activity in central pain pathways 10. Thus, the photophobia observed following de-epithelialization is likely to be due to a convergence of input from sensitized corneal afferent nociceptors with retinally connected thalamic neurons that respond to noxious stimulation as well as bright light. Similar mechanisms may explain the moderate-to-severe photophobia that can occur when nociceptors in non-corneal cranial structures may contribute, for example, migraine headache 19, meningitis 21, subarachnoid hemorrhage 6, as well as other ophthalmological conditions such as uveitis 37.

While TTX produced a significant attenuation of photophobia in de-epithelialized cornea, its application to the intact cornea had no effect on eye closure in response to bright light. This difference in the effect of TTX on the response to a bright light in normal control versus injured corneas might be due to TTX only being effective in reducing firing of neurons in an inflammatory or neuropathic state. In fact, while TTX appears not to be anesthetic with thermal and mechanical stimuli in non-neuropathic rats 15, it is antinociceptive in rodent neuropathic pain models, such as spinal nerve ligation 18, chronic constriction injury, and spared nerve injury 42, as well as in chemotherapy-induced neuropathy models (see Nieto et al., 23 for review). Importantly, TTX inhibits the Na(V) 1.7 sodium channel, which is upregulated in the setting of nerve injury and inflammation 3, 22, 39, at low nanomolar concentrations 9. While it is also possible that the lack of effect of TTX on the photophobia in intact corneas is related to the form of TTX used, the citrate salt that is polar and therefore may have more limited corneal penetration, in the present experiments we applied TTX at a very high (1 mM) concentration. Therefore, it is likely at high enough concentrations to reach corneal nociceptor terminals at effective (nanomolar 9) concentrations. Furthermore, a similar distinction was seen for the effect of lidocaine in rats with control and injured corneas.

Photophobia is a common disabling symptom that can occur following corneal damage (e.g. in corneal refractive surgery 4, corneal abrasion 32 or chemical injury 13). Corneal damage is also associated with other symptoms, most notably ocular pain, which is dependent, at least in part, on corneal nociceptor sensitization and ongoing nociceptor activity. Since the inhibition of photophobia by TTX is likely to be due to a decrease in corneal nociceptor activity, TTX may also be useful for the treatment of pain and other ocular symptoms associated with corneal injury of diverse etiologies. Although local anesthetics, such as lidocaine, can attenuate eye pain and photophobia, their corneal toxicity is well documented 20, impairing corneal re-epithelialization 5 and producing caspase-dependent corneal endothelial cell apoptosis 43. Thus due to the dose- and time-dependent corneal epithelial toxicity lidocaine and other local anesthetic use is contraindicated for chronic treatment of persistent ocular pain 11, 28. This is of particular importance since ocular pain after photorefractive keratectomy is one of the most important limitations of this surgery (most patients experience moderate to severe pain), with transition from physiological to neuropathic pain occurring in ~50% of patients within 1 month post-LASIK surgery 8, 40 (LASIK differs from photorefractive keratectomy in that the former uses a blade or laser to create a corneal flap, whereas in photorefractive keratectomy only the epithelium is removed and the layer just below the epithelium is then treated with a laser). While high dose TTX applied topically to the cornea has previously been shown to be able to produce long-lasting corneal anesthesia, in contrast to lidocaine, TTX does not produce in vitro cell toxicity and cell death 30, and in vivo TTX does not produce corneal or systemic toxicity at anesthetic concentrations 35, 36. Therefore TTX may be an effective therapeutic option to reduce the symptoms of photophobia that occurs after photorefractive keratectomy, as well as photophobia associated with other clinical diseases that involve corneal nociceptor sensitization (e.g. ocular inflammation 34, optic or trigeminal neuropathies 33, DES 33).

Perspective.

We show that lidocaine and tetrodotoxin (TTX) attenuate photophobia induced by corneal injury. While corneal toxicity limits use of local anesthetics, TTX may be a safer therapeutic option to reduce the symptom of photophobia associated with corneal injury.

Highlights.

Corneal injury produced an increased sensitivity to light (photophobia)

Tetrodotoxin and lidocaine had no effect on light aversive behavior in normal control rats

Tetrodotoxin and lidocaine both eliminated photophobia in rats with corneal injury

Because of lidocaine corneal toxicity, topical TTX may be a safer therapeutic option

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the UCSF Academic Senate Committee on Research and NIH grant NS085831.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Belmonte C, Acosta MC, Gallar J. Neural basis of sensation in intact and injured corneas. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berson DM. Phototransduction in ganglion-cell photoreceptors. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:849–855. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi RY, Kou XX, Meng Z, Wang XD, Ding Y, Gan YH. Involvement of trigeminal ganglionic Nav 1.7 in hyperalgesia of inflamed temporomandibular joint is dependent on ERK1/2 phosphorylation of glial cells in rats. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:983–994. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder PS. Optical problems following refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:739–745. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisla K, Tanelian DL. Concentration-dependent effects of lidocaine on corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:3029–3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Çavuş UY, Avci S, Sönmez E, Doğan MS, Gürer B. Isolated photophobia as a presenting symptom of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;122:138–139. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KY, Jones RR, Bark DH, Swift J, Parker JAJ, Haschke RH. Release of neuronotrophic factor from rabbit corneal epithelium during wound healing and nerve regeneration. Exp Eye Res. 1987;45:633–646. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao C, Golebiowski B, Stapleton F. The role of corneal innervation in LASIK-induced neuropathic dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2014;12:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dib-Hajj SD, Yang Y, Black JA, Waxman SG. The Na(V)1.7 sodium channel: from molecule to man. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Digre KB, Brennan KC. Shedding light on photophobia. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32:68–81. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3182474548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erdem E, Undar IH, Esen E, Yar K, Yagmur M, Ersoz R. Topical anesthetic eye drops abuse: are we aware of the danger? Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:189–193. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.744758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallar J, Acosta MC, Gutierrez AR, Belmonte C. Impulse activity in corneal sensory nerve fibers after photorefractive keratectomy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4033–4037. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham JS, Schoneboom BA. Historical perspective on effects and treatment of sulfur mustard injuries. Chem Biol Interact. 2013;206:512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katagiri A, Thompson R, Rahman M, Okamoto K, Bereiter DA. Evidence for TRPA1 involvement in central neural mechanisms in a rat model of dry eye. Neuroscience. 2015;290:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayser V, Viguier F, Ioannidi M, Bernard JF, Latremoliere A, Michot B, Vela JM, Buschmann H, Hamon M, Bourgoin S. Differential anti-neuropathic pain effects of tetrodotoxin in sciatic nerve- versus infraorbital nerve-ligated rats--behavioral, pharmacological and immunohistochemical investigations. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klugbauer N, Lacinova L, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Structure and functional expression of a new member of the tetrodotoxin-sensitive voltage-activated sodium channel family from human neuroendocrine cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:1084–1090. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampert A, O’Reilly AO, Reeh P, Leffler A. Sodium channelopathies and pain. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:249–263. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyu YS, Park SK, Chung K, Chung JM. Low dose of tetrodotoxin reduces neuropathic pain behaviors in an animal model. Brain Res. 2000;871:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maleki N, Becerra L, Upadhyay J, Burstein R, Borsook D. Direct optic nerve pulvinar connections defined by diffusion MR tractography in humans: implications for photophobia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:75–88. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGee HT, Fraunfelder FW. Toxicities of topical ophthalmic anesthetics. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:637–640. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller S, Mateen FJ, Aksamit AJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 meningitis: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurovirol. 2013;19:166–171. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukai M, Sakuma Y, Suzuki M, Orita S, Yamauchi K, Inoue G, Aoki Y, Ishikawa T, Miyagi M, Kamoda H, Kubota G, Oikawa Y, Inage K, Sainoh T, Sato J, Nakamura J, Takaso M, Toyone T, Takahashi K, Ohtori S. Evaluation of behavior and expression of NaV1.7 in dorsal root ganglia after sciatic nerve compression and application of nucleus pulposus in rats. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:463–468. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-3076-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieto FR, Cobos EJ, Tejada MA, Sanchez-Fernandez C, Gonzalez-Cano R, Cendan CM. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) as a therapeutic agent for pain. Mar Drugs. 2012;10:281–305. doi: 10.3390/md10020281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noseda R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, Gooley JJ, Saper CB, Digre K, Burstein R. A neural mechanism for exacerbation of headache by light. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:239–245. doi: 10.1038/nn.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okamoto K, Tashiro A, Chang Z, Bereiter DA. Bright light activates a trigeminal nociceptive pathway. Pain. 2010;149:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamoto K, Tashiro A, Thompson R, Nishida Y, Bereiter DA. Trigeminal interpolaris/caudalis transition neurons mediate reflex lacrimation evoked by bright light in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:3492–3499. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panneton WM, Hsu H, Gan Q. Distinct central representations for sensory fibers innervating either the conjunctiva or cornea of the rat. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel M, Fraunfelder FW. Toxicity of topical ophthalmic anesthetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:983–988. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.794219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearlman E, Sun Y, Roy S, Karmakar M, Hise AG, Szczotka-Flynn L, Ghannoum M, Chinnery HR, McMenamin PG, Rietsch A. Host defense at the ocular surface. Int Rev Immunol. 2013;32:4–18. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.749400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Castro R, Patel S, Garavito-Aguilar ZV, Rosenberg A, Recio-Pinto E, Zhang J, Blanck TJ, Xu F. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics in human neuronal cells. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:997–1007. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819385e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plainis S, Murray IJ, Carden D. The dazzle reflex: electrophysiological signals from ocular muscles reveal strong binocular summation effects. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26:318–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2006.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rittichier KK, Roback MG, Bassett KE. Are signs and symptoms associated with persistent corneal abrasions in children? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:370–374. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal P, Borsook D. The corneal pain system. Part I: the missing piece of the dry eye puzzle. Ocul Surf. 2012;10:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Doctor PP, Tauber J, Foster CS. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz DM, Duncan KG, Fields HL, Jones MR. Tetrodotoxin: anesthetic activity in the de-epithelialized cornea. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:790–794. doi: 10.1007/s004170050160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz DM, Fields HL, Duncan KG, Duncan JL, Jones MR. Experimental study of tetrodotoxin, a long-acting topical anesthetic. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selmi C. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheedy JE, Truong SD, Hayes JR. What are the visual benefits of eyelid squinting? Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:740–744. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shields SD, Cheng X, Uceyler N, Sommer C, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Sodium channel Na(v)1.7 is essential for lowering heat pain threshold after burn injury. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10819–10832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0304-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shtein RM. Post-LASIK dry eye. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2011;6:575–582. doi: 10.1586/eop.11.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang XL, Elgjo K, Haaskjold E. Regeneration of rat corneal epithelium is delayed by the inhibitory epidermal pentapeptide (EPP) Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996;74:361–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie W, Strong JA, Meij JT, Zhang JM, Yu L. Neuropathic pain: early spontaneous afferent activity is the trigger. Pain. 2005;116:243–256. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu HZ, Li YH, Wang RX, Zhou X, Yu MM, Ge Y, Zhao J, Fan TJ. Cytotoxicity of lidocaine to human corneal endothelial cells in vitro. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;114:352–359. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]