Abstract

Medicaid churning - the constant exit and re-entry of beneficiaries as their eligibility changes - has long been a problem for both Medicaid administrators and recipients. Churning will continue under the Affordable Care Act, because despite new federal rules, Medicaid eligibility will continue to be based on current monthly income. We developed a longitudinal simulation model to evaluate four policy options for modifying or extending Medicaid eligibility to reduce churning. The simulations suggest that two options, extending Medicaid eligibility either to the end of a calendar year or for twelve months after enrollment, would be far more effective in reducing churning than the other options of a three-month extension or eligibility based on projected annual income. States should consider implementation of the option that best balances costs, including both administration and services, with improved health of Medicaid enrollees.

Medicaid “churning” - the constant exit and re-entry of beneficiaries as their eligibility changes - has long frustrated Medicaid administrators concerned with providing continuity of medical care while reducing unnecessary administrative costs.1,2,3,4,5 Recent research estimating the numbers of people whose Medicaid eligibility might change from year to year due to changes in income or family size has underscored how churning will continue under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).6,7,8 Estimates based on data from 2004–2008 indicate that more than 30 percent of Medicaid eligibles lose eligibility within six months of enrollment and about half lose eligibility within twelve months.7,8 These estimates should remain valid, as the ACA does not change the requirement that current monthly income serve as the basis for Medicaid eligibility.9 The estimates also align with ACA provisions by assuming eligibility ends when a person’s monthly income increases above 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).7,8

In part to address Medicaid churning caused by fluctuating income or enrollees not providing documents required to recertify eligibility, the ACA provided substantial federal funding to states to modernize the computer systems that determine Medicaid eligibility. This modernization should increase efficiencies in eligibility determination, particularly by enabling verification of income with electronic data from other federal and state agencies. Moreover, eligibility will be renewed administratively (without enrollees needing to provide documentation) if enrollees’ Medicaid records match electronically with other agencies’ verification data that indicate continuing eligibility.

However, even with greater use of electronic data linkages, failed matches and data inconsistencies will sometimes trigger dis-enrollments of eligible people. Moreover, because monthly income changes frequently in lower-income households, states’ ability to electronically verify income every quarter will lead to churning unless states choose to develop mitigating procedures.

We developed a longitudinal simulation model to evaluate four options to reduce Medicaid churning under the ACA by modifying or extending Medicaid eligibility. Two are substantially more effective in reducing churning but they have different impacts on average monthly caseloads and the number of people covered all year. Choosing between the options illustrates the trade-offs policymakers face when considering Medicaid program costs and costs to Medicaid enrollees who might churn.

Background

Medicaid churning involves a pattern of short-term enrollment, dis-enrollment, and re-enrollment that often occurs year after year. The typical causes are seasonal employment or overtime that increase earnings so a person loses eligibility for some months, only to become eligible again and re-enroll when the extra income ends. Churning is distinct from transitions to other insurance coverage associated with longer-lasting changes in income or employment or marital status. Churning and more permanent transitions have different cost implications for society and individuals.

Churning creates substantial administrative costs for Medicaid and Medicaid managed care plans. From 2005 to 2010, estimated administrative costs per enrollment or disenrollment ranged between $180 and $280.3,10,11 In 2015, the administrative cost of one person churning once (dis-enrolling and re-enrolling) could be from $400 to $600 (accounting for cost increases since 2005). To put this estimate in perspective, in fiscal year 2011 (the most recent year available) average Medicaid expenditures for a non-aged, non-disabled adult were $4,141.12 Churning-related administrative costs, multiplied by the number of people who churn in a year, generate a significant share of Medicaid expenses.

Churning also contributes to increased Medicaid expenditures for medical care. People who experience lapses in coverage often re-enroll in Medicaid when, for example, they obtain high-cost care in hospitals that could have been avoided with better ongoing care.13,14,15

Churning-related administrative costs and costs of avoidable medical care fall on taxpayers. Other costs fall on individuals who experience churning. In order to re-enroll they have to provide documentation to re-establish eligibility, and may have to change health care providers, a process that disrupts medical care and contributes to health problems. Research also has shown that people with short episodes of coverage have poorer quality of health care than people enrolled for longer episodes.11,16,17 In short, costs to taxpayers and to eligible individuals would be substantially lower if Medicaid churning were reduced.

Churning and the Affordable Care Act

In issuing two final federal rules in 2012 regarding income calculations for Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, the Department of Health and Human Services recognized that monthly income changes can cause churning.9 Federal rule §435.603(h)(2) allows states to use projected annual income for the remainder of the calendar year when evaluating a person’s eligibility for Medicaid. The projection is in contrast to the previous rule requiring people to enroll and then disenroll from Medicaid if their current monthly income qualifies them for Medicaid but their projected annual income for the entire calendar year (including previous months) exceeds the Medicaid limit. The new rule enables someone in these circumstances to remain in a marketplace plan with a premium subsidy. The other federal rule, §435.603(h)(3), allows states to include or exclude a prorated portion of a predictable income change when determining current eligibility. This rule aims to reduce churning among people expecting income changes due to seasonal employment or overtime.

Options for Reducing Churning

Many strategies have been proposed to reduce Medicaid churning and provide continuity of coverage for beneficiaries.1,6, 8,18 We focus on four policy options intended to minimize churning: (1) annualize income when determining Medicaid eligibility (similar to federal rule §435.603(h)(2)); (2) if a quarterly income verification check indicates an enrollee is no longer eligible, extend Medicaid coverage by three months or (3) extend coverage to the end of the calendar year; and (4) grant initial coverage for 12 continuous months. The options involve procedures that could simplify the recertification of Medicaid eligibility and avoid disruptions in coverage commonly caused by income fluctuations, administrative errors, and enrollees’ not fulfilling re-certification requirements.

We discuss the options in more detail after describing the model used to simulate the effects of each option.

Simulation Model and Data

The longitudinal simulation model uses monthly income data in the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to create spells of Medicaid eligibility under current ACA rules. SIPP is a nationally representative survey, and our simulations use all the data on monthly changes in income and family structure in the SIPP. The simulations estimate the effects of the four policy options under the circumstances originally envisioned by the ACA; we assume all states opted to expand Medicaid eligibility for adults to 138 percent FPL.

Our simulation year is calendar year 2006, the last calendar year in the 2004–2007 SIPP panel with 12 months of data for all sampled individuals. We use the 2004–2007 SIPP panel rather than the 2008–2012 panel because 2006 was a year of relative economic prosperity, and we do not want to confound our simulation results with the Great Recession’s impact on Medicaid enrollment.

Our simulations are for adults 19 to 64 years of age at the end of 2006. Our SIPP sample consists of adults with data for the entire panel (48 months). We use the longitudinal weights provided by SIPP to make national estimates from this sample. However, to better correct for any attrition bias associated with health insurance status, we revised the longitudinal weights to match estimates of the distribution of health insurance status in the last month of SIPP using the cross-sectional SIPP weight for that month.6

Estimates of policy outcomes were simulated with two different assumptions about monthly participation rates (85 and 50 percent) after a year of eligibility. Two different administrative disruption rates (35 and 15 percent) were assumed to simulate the dis-enrollment at the annual redetermination of continuing eligibility. The online Appendix provides further details on the longitudinal simulation model and the rationale for our choices of participation and administrative disruption rates.19

Outcomes Simulated

The simulation model allows us to estimate the number of people ever covered by Medicaid in the calendar year and the number covered throughout the calendar year, as well as the number of transitions into and out of Medicaid and the number of people with at least one churning episode (that is, who exit and re-enroll) during the calendar year.

We also estimate the average monthly caseload for each option. The average monthly caseload is defined as total person-months of enrollment in the calendar year divided by 12. Thus, differences in monthly caseloads among the four options reflect differences both in the number of enrollees and length of enrollment per enrollee. Average monthly caseload is a good indicator of predictable spending on Medicaid covered medical services, assuming that such expenditures are roughly proportional to the number of people enrolled each month.

Baseline Scenario

A counterfactual comparison is needed to quantify the effects of the policy options so we first simulated coverage in a “baseline” scenario. The scenario assumes that people do not report changes in their income or family size affecting their monthly eligibility. Enrollees leave Medicaid only when a quarterly check of administrative data or the annual redetermination of eligibility reveals that they are no longer eligible. The simulation model also assumes administrative disruptions occur during annual eligibility redeterminations; causes of such disruptions include clerical errors or enrollees not providing documentation after discrepancies between electronic records generate a disenrollment notice. Disruptions cause a percentage of enrollees to be dis-enrolled, despite their continuing eligibility for Medicaid.

Four Policy Options Simulated

Option 1: Annualize Income When Determining Medicaid Eligibility

Annualizing income when determining eligibility would reduce churning that predictably occurs each year. This option is similar in spirit to the previously discussed federal rules §435.603(h)(2) and §435.603)h)(3), ACA provisions designed to address income fluctuation. In simulating this option, income is annualized by assuming that monthly income in each of the remaining months of the calendar year will continue at the current monthly level and then adding actual income from the previous months. If either current monthly income or the projection of average monthly calendar-year income is less than the eligibility limit in any month, then the person is considered eligible for Medicaid in that month.

Option 2: Extend Medicaid Coverage by Three Months

When a change in income or life-circumstances causes loss of eligibility, Medicaid beneficiaries must be given ten-days advance notice that they are no longer eligible. Coverage generally stops at the end of the month in which the eleventh day occurs. An exception to this general rule is a program known as Transitional Medicaid Assistance (TMA), which provides between 4 and 12 months of additional Medicaid coverage to families who otherwise would lose eligibility because an adult family member has higher earned income from more work hours or because spousal or child support payments increased.18,20 TMA sets a precedent for extending Medicaid eligibility by three months if an income verification check indicates that a Medicaid enrollee has lost eligibility. In our simulation of this option, someone loses coverage only if a second verification check confirms a continuing lack of eligibility.

Option 3: Extend Medicaid Coverage to End of Calendar Year

This option extends coverage until the end of the calendar year for those newly enrolled or anyone for whom a quarterly check of administrative data confirmed eligibility earlier in the year. It effectively causes annual redeterminations of eligibility to coincide with the open enrollment period for the ACA health insurance marketplace. This makes it easier for people losing Medicaid eligibility because of increased income to enroll in a marketplace health plan without a gap in coverage.

Option 4: Grant Coverage for Twelve Continuous Months

Twelve months of continuous eligibility is now a state option for children covered by either CHIP or Medicaid.21 Adults can be given twelve months of continuous coverage if a state requests an 1115 waiver to do so; so far, only New York has obtained such a waiver for parents.22 Option 4 eliminates the need for a state to request an 1115 waiver. Adults would be granted Medicaid for twelve months from the date of their initial or annual eligibility determination and would retain Medicaid for twelve months even if a change in income or life-circumstances would otherwise make them ineligible.

Limitations

As with results of all simulation models, our estimates have several limitations that should be kept in mind. First, the SIPP monthly income data are self-reported, and might not match perfectly with income as assessed by state Medicaid programs. Second, as we noted, our sample is limited to people who remained in the SIPP for the full panel. We revised the longitudinal weights supplied by SIPP to better correct for any attrition bias associated with health insurance status. Nonetheless, we may still be underestimating churning if people who left the SIPP sample were particularly likely to cycle on and off of Medicaid. Third, by using all the respondents in the nationally representative SIPP sample who met our selection criteria, the simulations implicitly assume that all states expanded Medicaid eligibility. Given our desire for greater statistical power with a larger sample and the strong financial incentives for states to expand Medicaid, we made the simplifying assumption that all states would expand Medicaid eligibility to 138 FPL. Finally, we focus just on Medicaid churning, rather than other pathways people might take out of Medicaid. Thus we simulate only the effects of policy options that might reduce churning; we do not consider other strategies to improve continuity of coverage, such as the participation of managed care plans in both Medicaid and the insurance marketplaces.18

Results

Exhibit 1 shows the simulation results for the baseline scenario and the four policy options when we assume that 85 percent of unenrolled Medicaid eligible adults enroll (participate) each month and the administrative disruption rate is 15 percent. Exhibits 2, 3, and 4 illustrate, respectively, how each of the four policy options changes our three outcomes of interest: the number of adults re-enrolling in Medicaid (churning), the number covered by Medicaid all year, and the average monthly Medicaid caseload. The changes are shown as percentage changes relative to the baseline.

Exhibit 1.

Simulated Medicaid Coverage in 2006 (in Millions) for Baseline Scenario and Four Policy Options, Assuming 85% Participation Rate and 15% Administrative Disruption

| Scenario | Covered any time in 2006 | Average monthly caseload in 2006 | Covered all months in 2006 | Churning: Leaving and re-entering in 2006* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | Number | Number | |

| Baseline Scenario | ||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 41.2 | 25.6 | 7.6 |

| Policy Options | ||||

| (1) Annualized income | ||||

| Persons covered | 58.4 | 42.9 | 27.3 | 8.1 |

| Change from baseline | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| (2) 3-month Extension | ||||

| Persons covered | 57.4 | 42.4 | 26.6 | 7.6 |

| Change from baseline | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0 |

| (3)End-of Calendar Year Extension | ||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 46.8 | 38.5 | 1.8 |

| Change from baseline | 0 | 5.6 | 12.9 | −5.9 |

| (4) 12-month Continuous Eligibility | ||||

| Persons covered | 60.6 | 48.0 | 30.6 | 5.4 |

| Change from baseline | 3.5 | 6.8 | 5.0 | −2.3 |

Source: Authors’ simulation model using 2004–2007 Panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Notes: The weighted estimate of the U.S. population of adults under age 65 is 181.877 million.

Includes people covered in December 2005 who disenrolled in January 2006 and re-entered later in the year.

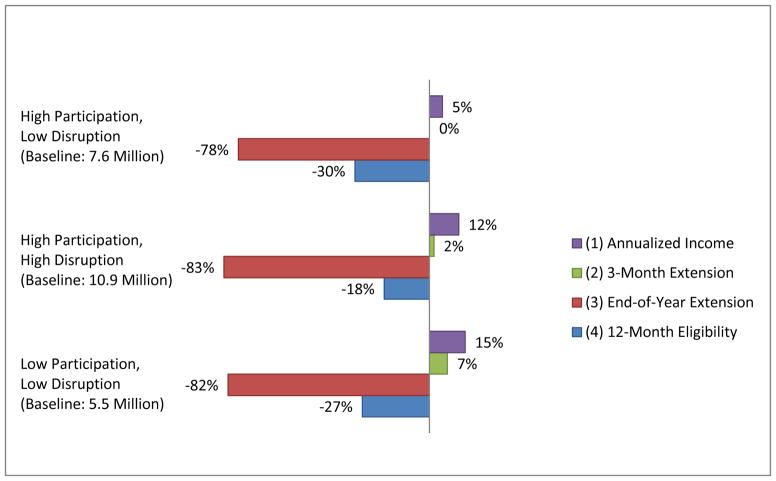

Exhibit 2.

Four Policy Options’ Estimated Effects on Percentage Change in Adults with Medicaid Churning, with Three Alternative Pairs of Simulation Assumptions

Source: Authors’ simulation model using 2004–2007 Panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Notes: High Participation and Low Participation are assumed Medicaid participation rates of 85% and 50%, respectively. High Disruption and Low Disruption are assumed administrative disruption rates of 35% and 15%, respectively.

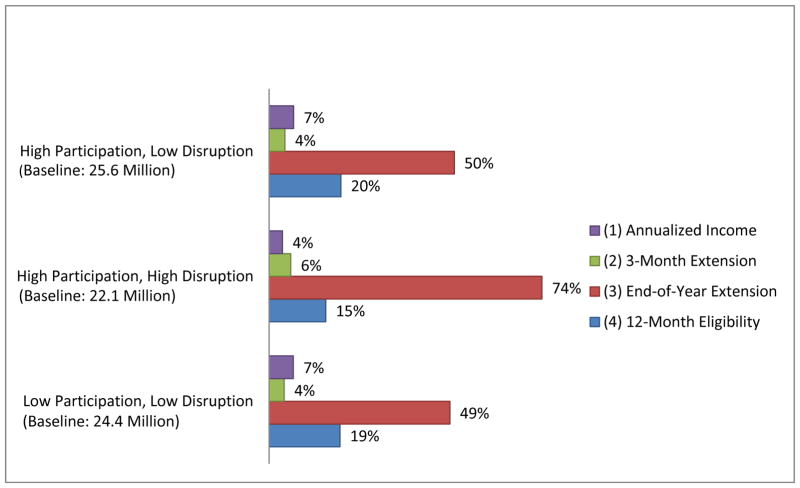

Exhibit 3.

Four Policy Options’ Estimated Effects on Percentage Change in Adults Covered All Year by Medicaid, with Three Alternative Pairs of Simulation Assumptions

Source: Authors’ simulations using 2004–2007 Panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Notes: High Participation and Low Participation are assumed Medicaid participation rates of 85% and 50%, respectively. High Disruption and Low Disruption are assumed administrative disruption rates of 35% and 15%, respectively.

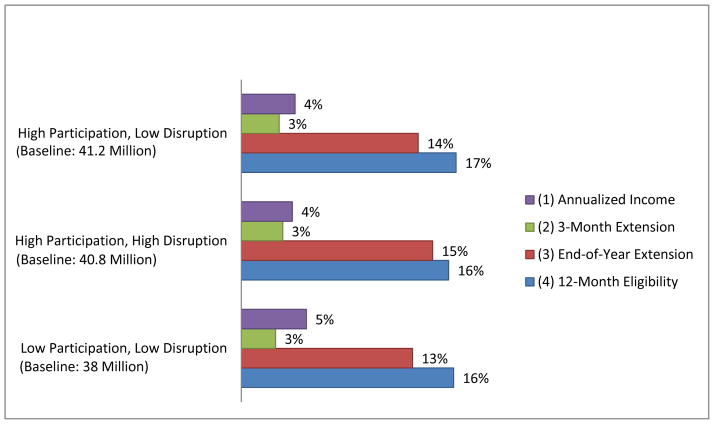

Exhibit 4.

Four Policy Options’ Estimated Effects on Percent Change in Average Monthly Medicaid Caseload, with Three Alternative Pairs of Simulation Assumptions

Source: Authors’ simulations using 2004–2007 Panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Notes: High Participation and Low Participation are assumed Medicaid participation rates of 85% and 50%, respectively. High Disruption and Low Disruption are assumed administrative disruption rates of 35% and 15%, respectively.

Exhibits 2, 3, and 4 also show how these three outcomes are affected by varying the Medicaid participation rate while holding the administrative disruption rate at 15%, and the effects of varying the disruption rate while holding the participation rate at 85%.

Our discussion of the simulated effects of the policy options focuses on the simulations when the participation rate is 85 percent and the disruption rate is 15 percent. Recall that the simulations are for calendar year 2006 and are applied to national data, as if all states expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA.

Results by Policy Option

Option 1 - annualize income

Compared to the baseline scenario, annualizing income increases the number of people re-enrolling (churning) in Medicaid by 5 percent (400,000 people; see Exhibits 1 and 2). Option 1 also is estimated to increase the number of people covered by Medicaid for the entire year by 7 percent (1.7 million more people) as well as the average monthly caseload by 4 percent (coincidentally also 1.7 million people).

Option 2 - three-month extension

Compared to the baseline scenario, extending enrollment for three months after a failed verification check has virtually no effect on the number of adults re-enrolling during the year. The number of adults covered all year increases by 4 percent (1.1 million people) and the average monthly caseload by 3 percent (1.2 million people).

Option 3 - end-of-calendar-year extension

By design, administrative disruption during the calendar year is almost eliminated with this option. Relative to the baseline scenario, churning drops by 78 percent (a decline of 5.9 million people). The number covered by Medicaid for the entire calendar year increases by 50 percent (an additional 12.9 million people) and the average monthly caseload increases by 14 percent (5.6 million people).

Option 4 - twelve months of continuous eligibility

Compared to the baseline scenario, this option reduces the number of people churning by re-enrolling in Medicaid by 30 percent (2.3 million fewer people). Twenty percent more people (5.0 million) are covered all year and the average monthly caseload increases by 17 percent (6.8 million more people). Among the four options, twelve months of continuous eligibility maximizes the number of people covered at some point in a calendar year (60.6 million).

Sensitivity of Results to Assumptions

As noted, Exhibits 2 through 4 illustrate how sensitive the estimated outcomes are to alternative assumptions about the administrative disruption and Medicaid participation rates. Option 3 (the end-of-calendar-year extension) is particularly effective in reducing churning and increasing all-year coverage in the face of a high disruption rate. This option moves the redetermination of eligibility to the end of the calendar year as soon as a person’s eligibility is verified once, so an otherwise high disruption rate contributes little to churning. Option 4 (twelve months of continuous eligibility), on the other hand, is sensitive to the disruption rate because coverage is conditioned on successful redetermination of eligibility during the calendar year. In contrast, the increase in average monthly caseload associated with each of the policy options is not particularly sensitive to the participation rate.

Discussion

Before conducting these simulations, we were unsure of the relative effects of these four options on the outcomes of interest. In particular, we did not foresee that annualizing income would have only modest effects on the number of people churning during a year and the number covered by Medicaid all year. Annualizing income has limited impact on churning largely because more people are eligible to re-enroll in Medicaid with the possibility of satisfying either of two possible income standards (current monthly income or annualized income).

Medicaid churning within a calendar year declines the most (78 percent) with Option 3 because it extends coverage through December for enrollees whose initial eligibility was verified sometime during the year. This explains why most adults who otherwise would have experienced churning during the year do not, and why Option 3 yields the greatest increase in the number of people covered throughout the year.

In the near term, Option 3 might create a greater workload for state employees in November and December by aligning eligibility redetermination for everyone already enrolled in Medicaid with the ACA’s fall open enrollment period. In time, however, the new state IT systems that permit automated enrollment and eligibility redetermination should make it possible for most Medicaid enrollees to have their eligibility redetermined in the same two-month period as the ACA open enrollment. Moreover, by enabling enrollees to remain Medicaid-eligible through the open enrollment period, Option 3 is consistent with the rationale for final rule §435.603(h)(2). It enables people to remain in a marketplace health plan rather than churn in and out of Medicaid if their current monthly income falls below the Medicaid eligibility limit.

Option 4, by guaranteeing coverage for twelve months after a person’s initial and subsequent eligibility redeterminations, eliminates churning by the person for a year. However, Option 4 is less effective than Option 3 (the end-of-calendar-year extension) in reducing churning within the calendar year. This is because a share of enrollees have their annual redeterminations of eligibility occur each month under Option 4, and some people are found to be ineligible at their redetermination. Many of these people will become eligible again and re-enroll with another twelve months of coverage, so Option 4 yields a larger increase in the average monthly Medicaid caseload than Option 3. Covering more people each month suggests that Option 4 is more costly than Option 3 in terms of Medicaid expenditures for medical care.

Implication for States: Trade-offs

The estimated outcomes of the four policy options help illuminate the trade-offs states face with respect to the issue of churning. From a state budget perspective, high rates of churning are undesirable because they increase Medicaid administrative costs and less predictable expenditures on avoidable utilization of medical care by people who churn. But churning also creates smaller monthly patient caseloads, which is attractive because budgeted Medicaid medical expenditures are lower. By reducing churning, a state gains control of the less predictable Medicaid expenses in exchange for higher predictable monthly caseload expenditures.

How a state views this cost trade-off depends on several factors that vary by state: financial well-being, willingness to extend Medicaid eligibility to low-income residents, and the extent of churning in its current Medicaid program.8 This cost trade-off calculus also might include net costs to individuals caused by interrupted medical protocols and lower quality of care due to churning.

If states were to adopt Options 3 or 4, the average monthly caseload would increase by 5.6 to 6.8 million adults, respectively (14 to 17 percent). This range is close to an estimated base case increase in Medicaid enrollment that suggested an additional 7,400 physicians would be needed to care for the newly eligible adults.23 In the short run, the increased enrollment may strain existing providers, especially if some of the newly-eligible adults have previously undiagnosed health conditions. But Medicaid managed care plans will likely increase their use of nurses and nurse practitioners to alleviate physician shortages. Over time, with less churning and more consistent, coordinated care, enrollees’ needs for care and Medicaid medical expenditures should stabilize.

States that do not try to reduce churning are likely to experience increased churning going forward. As with already eligible adults, newly-eligible adults are likely to enroll only when they have a medical problem that involves hospital care. Unless such enrollees are receiving continued care, they will let their enrollment lapse and then re-enroll when they have another health problem. Such churning will increase the costs of avoidable hospital care and the uncertainty in a state’s Medicaid budget.

Creativity in federal reimbursement of specific costs could encourage states to adopt options to reduce churning. For example, Medicaid administrative costs are generally equally shared by the state and federal governments but some administrative costs are matched at a higher federal rate than 50 percent. The federal administrative matching rate could be raised to 75 percent (or more) for states that met a threshold reduction in churning along with an increase in enrollment of adults. Similarly, the federal matching rate could be raised substantially for states that adopt more efficient IT systems to facilitate appropriate program eligibility during open enrollment or maintain Consumer Assistance Programs that help people understand their eligibility for Medicaid. Other federal funds might be made available for state efforts to locate “hot spots” where there are relatively high numbers of Medicaid enrollees with very high medical expenses – and tie such funds to a state’s reduction in churning among newly enrolled people.

Conclusion

Our simulations demonstrate that if states want to reduce Medicaid churning, extending coverage to the end of the calendar year (Option 3) and providing coverage for twelve months (Option 4) are the most effective among the four policy options we examined. Because Option 3 provides fewer months of continuous coverage than Option 4, it has a smaller impact on the average monthly caseload of enrollees during a calendar year. Lower average monthly caseloads suggest smaller Medicaid expenditures for medical services. On the other hand, higher average monthly caseloads indicate more people are covered continuously by Medicaid. Continuity of coverage is good for the enrollees’ health and reduces less predictable Medicaid spending for avoidable care that often occurs because of churning.

The federal government also has an interest in reducing churning. Creative changes in the federal matching rates could incentivize state efforts to reduce churning and improve the health of millions of Americans.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jeanne Spicer, from Penn State’s Population Research Institute, for assistance with the simulation programming; Tracy Johnson for expert assistance; Ben Sommers and John Graves for answering questions; and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. They are not responsible for any errors that may remain. The authors also are grateful to the Commonwealth Fund for financial support. Dr. Uberoi was a graduate student at Penn State University when the paper was written. The views presented here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers or staff, or the Congressional Research Service.

Appendix (for reviewers) – and to be available online

Monthly Medicaid eligibility in the simulations is based on monthly family income as a percent of the FPL, with the eligibility threshold set at the greater of 138% FPL or the state’s pre-ACA income limit for working adults, according to the presence of children.1 Family income is defined by summing all of the income reported for each family member in a given month, and then dividing by the appropriate poverty threshold according to family size and age of head. Although our simulation is limited to adults, the number of children in a family is considered when we calculate income as a percent of FPL. There are 15,073 adults in the sample. To assign people to families based on a nuclear family concept, “sub-family” identifiers in SIPP are used where applicable; otherwise family identifiers are used. In all simulations, anyone with income above the simulated Medicaid eligibility threshold who reported Medicaid coverage in SIPP is assigned Medicaid eligibility and coverage for that month. Thus, our analyses preserve all reported Medicaid coverage above the income levels where we simulate eligibility and participation.

After assigning monthly eligibility and spells of eligibility according to family income as a percent of FPL, we use a dynamic participation algorithm to assign Medicaid coverage. This algorithm assumes that the probability of not participating decreases exponentially over the first twelve months of continuous eligibility, according to the formula (1 – P)M/12, so that the monthly probability of participation increases to P (and remains there) after twelve months. We assume P equals 0.85 for our “high” participation rate and P equals 0.50 for our “low” participation rate. (These choices of high and low participation rates are based on estimates in the literature.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) Once people are simulated as deciding to enroll, they continue to participate for as long as they remain eligible, except for administrative disruptions associated with the annual redetermination of eligibility.

To account for redetermination as a factor in Medicaid churning, we define an administrative disruption rate as the probability that a person who is still eligible for Medicaid will exit at the one-year anniversary of enrollment because of errors caused by administrative problems or enrollees who delay in providing documentation of continued eligibility. Anyone who exits Medicaid in this fashion in the simulation, and remains eligible, has a high probability (equal to 0.85) of re-enrolling in each subsequent month of eligibility. We report results from simulations with a 15 percent administrative disruption rate, but we also consider the effects of increasing the administrative disruption rate to 35 percent (see Appendix Exhibits 1–3).

Our assumptions regarding low and high rates of administrative disruption are based on research related mostly to children’s disenrollment from Medicaid in the early to mid-2000s. Three different sources support the use of an administrative disruption rate on the order of 15% in our primary simulations. First, using national survey data, Sommers estimated that an average of 12.6% of children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP “dropped out” within a year, “despite apparently remaining eligible and having no other insurance.” The highest drop-out rate for children by state was 26%.8 Second, of approximately 500,000 children enrolled in Medicaid in South Carolina in 2011, 12% (60,000) disenrolled and then returned within a month and 18% (90,000) disenrolled and returned with a year.9 Third, according to a report on Medicaid churning in Massachusetts, the program closed 1.5% of its caseload each month for administrative reasons, which corresponds to 18% of annual reviews if one-twelfth of the caseload was reviewed each month. About 11,000 of the cases opened each month were active within the preceding 90 days, approximately one-third of average monthly closings (and 12% of the cases up for annual review).10 Since Sommers has reported that adults with continuing eligibility drop out of Medicaid at nearly twice the rate for children,11 as well as child drop-out rates in some states that are twice the national average, we chose 35% as a relatively high rate of administrative disruption for our sensitivity analyses.

In order to simulate spells of eligibility and coverage in progress at the start of 2006, we begin to simulate participation decisions in January 2005 and continue the simulation through December 2006. From an initial simulation that assumed everyone eligible for Medicaid in January 2005 was newly eligible, we simulated coverage for all of 2005 and determined the percentage of people who were eligible in January 2006 who were also enrolled in December 2005 (and would have automatically continued on Medicaid in January 2006). This percentage is used in assigning coverage spells in progress at the start of the dynamic simulation in January 2005. Additionally, we randomly assign anniversary months (which trigger the possibility of administrative disruption) to spells in progress in January 2005.

All simulations reflect the fall open enrollment season for the marketplaces, which has the effect of screening a high proportion of the lower-income population for Medicaid eligibility late in every calendar year. Thus, the fall open enrollment season introduces a seasonal spike in new enrollments that was not a factor in Medicaid dynamics prior to the ACA.

In projecting Medicaid enrollment under current ACA rules, we initially developed two baseline scenarios. The first baseline scenario simulates the hypothetical situation where spells of Medicaid eligibility and enrollment under the ACA are strictly determined by monthly income (as reported in SIPP). In effect, this scenario assumes “perfect enforcement” of monthly Medicaid eligibility; enrollees are only disenrolled if monthly income exceeds 138% FPL, but they are immediately disenrolled whenever their monthly income exceeds the limit. In the second baseline scenario, involving “imperfect enforcement,” changes in income or family size that affect monthly eligibility are detected with a lag, only when a state’s quarterly check of payroll data or annual redetermination of eligibility reveals that someone is no longer eligible. Only then is a person are disenrolled. In effect, imperfect enforcement unofficially extends the coverage of some people who lose monthly eligibility, adding to months of Medicaid enrollment in the second scenario. However, in the second scenario, other enrollees are mistakenly dis-enrolled when their annual redetermination occurs (“administrative disruption”), which works to reduce months of Medicaid enrollment in the imperfect enforcement scenario. In the manuscript, all of the analyses are based on the baseline scenario with lags in the detection of eligibility losses. However, outcomes from both baseline scenarios are available for comparison here (see Appendix Exhibit 1).

Appendix Exhibit 1.

Simulated Medicaid Eligibility and Coverage in 2006 (in Millions) for Two Baseline Scenarios and Four Policy Options, Assuming 85% Participation Rate and 15% Administrative Disruption

| Scenario | Covered any time in 2006 |

Average monthly caseload in 2006 |

Covered all months in 2006 |

Transitioning into Medicaid in 2006 |

Transitioning from Medicaid in 2006* |

Leaving and re- entering in 2006* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Baseline Scenarios | ||||||||||||

| (1) Perfect enforcement | ||||||||||||

| Persons eligible | 59.7 | 32.8 | 40 | 22 | ||||||||

| Persons covered | 53.1 | 29.2 | 36.1 | 19.8 | 24.6 | 13.6 | 21.1 | 11.6 | 20.1 | 11 | 5.4 | 3 |

| (2) Imperfect enforcement, with quarterly wage check and annual redetermination of eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 31.4 | 41.2 | 22.7 | 25.6 | 14.1 | 20.7 | 11.4 | 22 | 12.1 | 7.6 | 4.2 |

| Policy Options | ||||||||||||

| Annualized income | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 58.4 | 32.1 | 42.9 | 23.6 | 27.3 | 15 | 20.1 | 11.1 | 22.1 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 4.4 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.9 | −0.6 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| 3-month Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.4 | 31.6 | 42.4 | 23.3 | 26.6 | 14.7 | 20.5 | 11.3 | 21.4 | 11.8 | 7.6 | 4.2 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.6 | −0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| End-of Year Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 31.4 | 46.8 | 25.7 | 38.5 | 21.2 | 15 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 3 | 1.8 | 1 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0 | 0 | 5.6 | 3 | 12.9 | 7.1 | −5.8 | −3.2 | −16.6 | −9.1 | −5.9 | −3.2 |

| 12-month Continuous Eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 60.6 | 33.3 | 48.0 | 26.4 | 30.6 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 9.4 | 18.3 | 10.1 | 5.4 | 3 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 3.5 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 2.7 | −3.6 | −2 | −3.7 | −2 | −2.3 | −1.2 |

Source: Authors’ simulation model using 2004–2007 SIPP Panel. Notes: Denominator for all percentages is the weighted estimate of the U.S. population of adults under age 65 (181.877 million). Counts of people transitioning into Medicaid, transitioning from Medicaid, and re-entering are not mutually exclusive.

Includes people covered in December 2005 who disenrolled in January 2006.

Appendix Exhibit 2.

Simulated Medicaid Eligibility and Coverage in 2006 (in Millions) for Two Baseline Scenarios and Four Policy Options, Assuming 85% Participation Rate and 35% Administrative Disruption

| Scenario | Covered any time in 2006 |

Average monthly caseload in 2006 |

Covered all months in 2006 |

Transitioning into Medicaid in 2006 |

Transitioning from Medicaid in 2006* |

Leaving and re- entering in 2006* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Baseline Scenarios | ||||||||||||

| (1) Perfect enforcement | ||||||||||||

| Persons eligible | 59.7 | 32.8 | 40 | 22 | ||||||||

| Persons covered | 53.1 | 29.2 | 36.1 | 19.8 | 24.6 | 13.6 | 21.1 | 11.6 | 20.1 | 11 | 5.4 | 3 |

| (2) Imperfect enforcement, with quarterly wage check and annual redetermination of eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 31.4 | 40.8 | 22.4 | 22.1 | 12.2 | 24 | 13.2 | 25.5 | 14 | 10.9 | 6 |

| Policy Options | ||||||||||||

| Annualized income | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 58.4 | 32.1 | 42.4 | 23.3 | 22.9 | 12.6 | 24.3 | 13.4 | 26.5 | 14.5 | 12.2 | 6.7 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| 3-month Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.4 | 31.6 | 42.1 | 23.1 | 23.4 | 12.9 | 24 | 13.2 | 24.7 | 13.6 | 11 | 6.1 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 0 | −0.8 | −0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| End-of Year Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 57.1 | 31.4 | 46.8 | 25.7 | 38.5 | 21.1 | 15 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 3 | 1.8 | 1 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3.3 | 16.4 | 8.9 | −9 | −5 | −20.1 | −11 | −9.1 | −5 |

| 12-month Continuous Eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 60.4 | 33.2 | 47.3 | 26 | 25.5 | 14 | 21.4 | 11.8 | 22.3 | 12.3 | 8.9 | 4.9 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 3.3 | 1.8 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 1.8 | −2.7 | −1.4 | −3.2 | −1.7 | −2 | −1.1 |

Source: Authors’ simulation model using 2004–2007 SIPP Panel. Notes: Denominator for all percentages is the weighted estimate of the U.S. population of adults under age 65 (181.877 million). Counts of people transitioning into Medicaid, transitioning from Medicaid, and re-entering are not mutually exclusive.

Includes people covered in December 2005 who disenrolled in January 2006.

Appendix Exhibit 3.

Simulated Medicaid Eligibility and Coverage in 2006 (in millions) for Two Baseline Scenarios and Four Policy Options, Assuming 50% Participation Rate and 15% Administrative Disruption

| Scenario | Covered any time in 2006 |

Average monthly caseload in 2006 |

Covered all months in 2006 |

Transitioning into Medicaid in 2006 |

Transitioning from Medicaid in 2006* |

Leaving and re- entering in 2006* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Baseline Scenarios | ||||||||||||

| (1) Perfect enforcement | ||||||||||||

| Persons eligible | 59.7 | 32.8 | 40 | 22 | ||||||||

| Persons covered | 48.7 | 26.8 | 33.8 | 18.6 | 24.1 | 13.2 | 17.3 | 9.5 | 16.4 | 9 | 3.3 | 1.8 |

| (2) Imperfect enforcement, with quarterly wage check and annual redetermination of eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 52.6 | 28.9 | 38 | 20.9 | 24.4 | 13.4 | 17.5 | 9.6 | 19 | 10.4 | 5.5 | 3 |

| Policy Options | ||||||||||||

| Annualized income | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 54.3 | 29.9 | 39.9 | 21.9 | 26 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 9.5 | 19.6 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 3.5 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 1.7 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.6 | 0.9 | −0.3 | −0.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| 3-month Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 52.9 | 29.1 | 39 | 21.4 | 25.4 | 14 | 17.7 | 9.7 | 18.5 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 3.3 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| End-of Year Extension | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 52.6 | 28.9 | 43 | 23.7 | 36.4 | 20 | 12.9 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2.8 | 12 | 6.6 | −4.6 | −2.5 | −14.6 | −8 | −4.5 | −2.4 |

| 12-month Continuous Eligibility | ||||||||||||

| Persons covered | 55.8 | 30.7 | 44.2 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 16 | 14.7 | 8.1 | 16.1 | 8.8 | 4.1 | 2.2 |

| Change from baseline (2) | 3.2 | 1.8 | 6.2 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 2.6 | −2.8 | −1.5 | −2.9 | −1.6 | −1.5 | −0.8 |

Source: Authors’ simulation model using 2004–2007 SIPP Panel. Notes: Denominator for all percentages is the weighted estimate of the U.S. population of adults under age 65 (181.877 million). Counts of people transitioning into Medicaid, transitioning from Medicaid, and re-entering are not mutually exclusive.

Includes people covered in December 2005 who disenrolled in January 2006.

References for Appendix

- 1.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Holding Steady, Looking Ahead: Annual Findings of a 50-State Survey of Eligibility Rules, Enrollment and Renewal Procedures, and Cost-Sharing Practices in Medicaid and CHIP, 2010–2011. 2011 Publication #8130, Jan. Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8130.pdf.

- 2.Sommers BD, Swartz K, Epstein AM. Policy Makers Should Prepare for Major Uncertainties in Medicaid Enrollment, Costs, and Needs for Physicians Under Health Reform. Health Affairs. 2011;30(11):2186–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elmendorf DW. Testimony Statement of Douglas W. Elmendorf, Director. Congressional Budget Office, before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, “CBO’s Analysis of the Major Health Care Legislation Enacted in March 2010. 2011 Mar 30; Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/03-30-healthcarelegislation.pdf.

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State by State Results for Adults At or Below 133% FPL. 2010 May; Available at: http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/Medicaid-Coverage-and-Spending-in-Health-Reform-National-and-State-by-State-Reseults-for-Adults-at-or-Below-133-FPL.pdf.

- 5.Sommers BD, Epstein AM. Medicaid Expansion – the Soft Underbelly of Health Care Reform? New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(22):2085–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin Group. The Health Benefits Simulation Model (HBSM): Methodology and Assumptions. 2009 Available at: http://www.lewin.com/content/Files/HBSMSummary.pdf.

- 7.Congressional Budget Office. Health Insurance Simulation Model: A Technical Description. 2007 Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/87xx/doc8712/10-31-HealthInsurModel.pdf.

- 8.Sommers BD. From Medicaid to Uninsured: Drop-Out Among children in Public Insurance Programs. Health Services Research. 2005;40(1):59–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser Family Foundation. Using Data and Technology to Drive Process Improvement in Medicaid and CHIP: Lessons from South Carolina. 2012 Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/using-data-and-technology-to-drive-process/

- 10.Seifert R, Kirk G, Oakes M. Enrollment and Disenrollment in Mass Health and Commonwealth Care. Massachusetts Medicaid Policy Institute; 2010. Available at. http://www.maxenroll.org/files/maxenroll/resources/EnrollmentinMHandCC-final-april2%20%282%29.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommers BD. Loss of Medicaid Among Non-Elderly Adults in Medicaid. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Endnotes

- 1.Sommers BD. From Medicaid to uninsured: drop-out among children in public insurance programs. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):59–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD. Why millions of children eligible for Medicaid and SCHIP are uninsured: poor retention versus poor take-Up. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):w560–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairbrother G, Dutton MJ, Bachrach D, Newall KA, Boozang P, Cooper R. Costs of enrolling children in Medicaid and SCHIP. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(1):237–243. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill I, Lutzky AW. Understanding SCHIP Retention. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2003. Is there a hole in the bucket? [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry M, Kannel S, Riley T, Pernice C. What parents say: why eligible children lose SCHIP. Portland (ME): National Academy for State Health Policy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Short PF, Swartz K, Uberoi N, Graefe D. Realizing health reform’s potential: maintaining coverage, affordability, and shared responsibility when income and employment change. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2011. May, (Issue Brief) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers BD, Rosenbaum S. Issues in health reform: how changes in eligibility may move millions back and forth between Medicaid and insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):228–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommers BD, Graves JA, Swartz K, Rosenbaum S. Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility changes will occur often in all states; policy options can ease impact. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(4):700–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Register. [Internet] Washington (DC): US Government Publishing Office; 2012. Mar 23, pp. 17156–7. [Cited 2015 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-03-23/html/2012-6560.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairbrother G. How much does churning in Medi-Cal cost? Los Angeles (CA): The California Endowment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ku L, MacTaggart P, Pouvez F, Rosenbaum S. Improving Medicaid’s continuity of coverage and quality of care. Washington (DC): Association for Community Affiliated Plans; 2009. Jul, [cited 2014 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.communityplans.net/Portals/0/ACAP%20Docs/ACAP%20MCQA%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young K, Rudowitz R, Rouhani S, Garfield R. Medicaid per enrollee spending: variation across states. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Issue Brief. 2015 Jan; [cited 2015 Apr 19]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-per-enrollee-spending-variation-across-states/

- 13.Hall AG, Harman JS, Zhang J. Lapses in Medicaid coverage: impact on cost and utilization among individuals with diabetes enrolled in Medicaid. Med Care. 2008;46(12):1219–25. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d695c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindman AB, Chattopadhyay A, Auerback GM. Medicaid re-enrollment policies and children’s risk of hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Med Care. 2008;46(10):1049–54. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185ce24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bindman AB, Chattopadhyay A, Auerback GM. Interruptions in Medicaid coverage and risk for hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):854–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenney GM, Pelletier JE. Monitoring duration of coverage in Medicaid and CHIP to assess program performance and quality. Acad Pediatrics. 2011;11(3S):S34–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson LM, Tang SS, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with discontinuous health insurance coverage. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):382–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP. Washington (DC): 2014. Mar, [cited 2014 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.macpac.gov/reports. [Google Scholar]

- 19.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 20.Kaiser Family Foundation. Transitional medical assistance (TMA): Medicaid issues update. Washington (DC): Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Key Facts; 2002. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ku L, Steinmetz E, Bruen BK. Continuous-eligibility policies stabilize Medicaid coverage for children and could be extended to adults with similar results. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(9):1576–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks T, Touschner J, Artiga S, Stephens J, Gates A. Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-state survey of eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015. Kaiser Family Foundation Report. 2015 Jan; [cited 2015 Jan 23]. Available from: http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-modern-era-medicaid-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-of-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-in-medicaid-and-chip-as-of-january-2015.

- 23.Sommers BD, Swartz K, Epstein A. Policy makers should prepare for major uncertainties in Medicaid enrollment, costs, and needs for physicians under health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2186–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]