Significance

Guanine-rich nucleic acids fold into a four-stranded structure named G-quadruplex that has implications in essential cellular processes, pharmaceutical applications, and nanodevices. We found a unique type of G-quadruplex that contains a G-vacancy and is stabilized by guanine derivatives such as te physiological concentration of GTP by fill-in at the G-vacancy of a guanine base. In response to changes in the concentration of guanine derivatives, this type of G-quadruplex is able to manipulate the tracking activity of protein on DNA as exemplified by a DNA polymerase-catalyzed DNA synthesis. Because guanine derivatives are natural metabolites in cells, such G-quadruplexes may potentially play an environment-responsive regulation in cellular processes, a functional property not found in the canonical G-quadruplexes.

Keywords: G-quadruplex, guanine-responsive, G-vacancy, nucleic acids

Abstract

G-quadruplex structures formed by guanine-rich nucleic acids are implicated in essential physiological and pathological processes and nanodevices. G-quadruplexes are normally composed of four Gn (n ≥ 3) tracts assembled into a core of multiple stacked G-quartet layers. By dimethyl sulfate footprinting, circular dichroism spectroscopy, thermal melting, and photo-cross-linking, here we describe a unique type of intramolecular G-quadruplex that forms with one G2 and three G3 tracts and bears a guanine vacancy (G-vacancy) in one of the G-quartet layers. The G-vacancy can be filled up by a guanine base from GTP or GMP to complete an intact G-quartet by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding, resulting in significant G-quadruplex stabilization that can effectively alter DNA replication in vitro at physiological concentration of GTP and Mg2+. A bioinformatic survey shows motifs of such G-quadruplexes are evolutionally selected in genes with unique distribution pattern in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms, implying such G-vacancy–bearing G-quadruplexes are present and play a role in gene regulation. Because guanine derivatives are natural metabolites in cells, the formation of such G-quadruplexes and guanine fill-in (G-fill-in) may grant an environment-responsive regulation in cellular processes. Our findings thus not only expand the sequence definition of G-quadruplex formation, but more importantly, reveal a structural and functional property not seen in the standard canonical G-quadruplexes.

G-quadruplexes are four-stranded structures formed in guanine-rich nucleic acids (1–3). Canonical G-quadruplexes are composed of four tracts of consecutive guanines connected by three loops. The guanines in the guanine tracts (G tracts) are packed in a core unit (Fig. 1A) of a stack of multiple G-quartet layers, each with four guanine bases connected by eight Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds (Fig. 1B). G-quadruplex–forming sequences are not randomly distributed in the mammalian genomes but concentrated at physiologically relevant positions (4): for instance, promoters, telomeres, and immuno-globulin switch regions. These facts suggest G-quadruplex structures have implications in physiological processes. Indeed, experimental investigations have demonstrated the physiological function of G-quadruplexes in many aspects (5–8).

Fig. 1.

Scheme of a stacked core unit (A) of a parallel G-quadruplex with three G-quartet layers. Each G-quartet (B) consists of four guanine bases (dashed polygon) connected by eight Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds (hashed bonds). The N7 in each guanine base is indicated in green. Removing one guanine from a G-quartet exposes the corresponding N7 (C, red circle).

Studies on G-quadruplexes have mostly focused on sequences described by a consensus of G≥3(N1–7G≥3)≥3, which can potentially form G-quadruplexes of three or more G-quartet layers with three loops of one to seven nucleotides (Fig. 1A) (9, 10). In recent years, the definition describing the capability of G-quadruplex formation has been broadened. Sequences with a loop up to 11 or 15 nucleotides were found capable of forming stable G-quadruplexes when the other two loops are sufficiently short (11, 12). The continuity of guanines in G tracts was also relaxed by the finding of G-quadruplexes with broken (13, 14) or bulged (15, 16) G tracts. Besides these intramolecular G-quadruplexes in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), we recently found a hybrid type of G-quadruplexes involving G tracts from both DNA and RNA transcript can form during transcription in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (16–19). In this case, a G-quadruplex may form with as few as two G tracts defined by G≥3(N1–7G≥3)≥1 on the nontemplate DNA strand instead of four. Although the DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplexes of three or more G-quartets are very stable, less stable hybrid G-quadruplexes of two G-quartets can also form in transcription (19). Moreover, our study showed a DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex could form in transcribed mitochondrial DNA in competition with a bulge-bearing G-quadruplex, which may participate in priming the initiation of DNA replication (16). This example demonstrates that the structural polymorphism of G-quadruplexes has implications in physiological processes.

In this work, we describe a unique type of G-quadruplex bearing a guanine vacancy (G-vacancy) in a G-quartet layer. Such structures can form with one G2 and three G3 tracts in ssDNA and in transcribed dsDNA as well. By accepting a guanine base from guanine derivatives, such as GMP or GTP in solution, the G-vacancy is filled up to form an intact core unit, resulting in an enhanced thermal stability of the G-quadruplexes in a concentration- and charge-dependent manner. At physiological concentration of GTP and Mg2+, the stability enhancement can significantly affect in vitro DNA replication. In supporting the formation and functional role of the G-vacancy–bearing G-quadruplexes (GVBQ) in cells, we found that sequences with potential to form GVBQ are preferentially selected at the 5′ end of genes in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms. Because guanine derivatives are natural metabolites in cells, we speculate the GVBQs may provide regulation in response to intracellular level of guanine derivatives, making them distinctive from the canonical G-quadruplex structures.

Results

G-Quadruplex Formation in G2/3G3 ssDNA and G-Quartet Completion by G Fill-In.

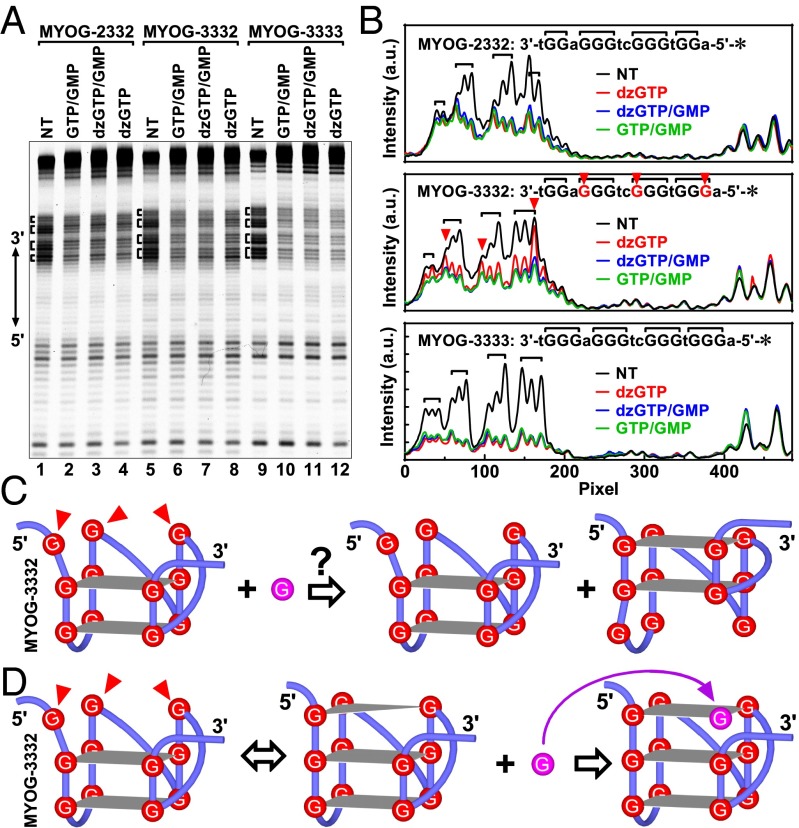

Previous studies in our laboratory suggested that GMP or GTP might affect the structure of the G-quadruplex. To perform a systematic investigation, we first studied three ssDNAs containing a native (MYOG-3332) or modified G-core (MYOG-2332 and MYOG-3333) sequence from the MYOG (Myogenin) gene of human in 50 mM K+ solution containing PEG 200. The three MYOG DNAs effectively formed intramolecular G-quadruplex as judged from a native gel electrophoresis (Fig. S1). Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy showed, with a characteristic positive peak at 295 and 265 nm, the MYOG-2332 might form an antiparallel G-quadruplex, whereas the other two DNAs might form a parallel G-quadruplex according to the positive peak at 265 and negative peak at 245 nm (Fig. 2A).

Fig. S1.

G-quadruplexes of DNAs resolved by native gel electrophoresis. The intramolecular nature of the G-quadruplexes is indicated by their faster migration in comparison with that of the M-21 random oligomer. Sequence and size of each DNA are listed below the gel. DNA (0.5 μM) was prepared in the same way as for the CD analysis and electrophoresed at pH 7.4 in the presence of 50 mM K+ and 40% (wt/vol) PEG 200.

Fig. 2.

G-quadruplex formation in MYOG G-core ssDNAs detected by (A) CD spectroscopy and (B and C) DMS footprinting. (A) CD spectra of MYOG G-quadruplexes. (B) DNA cleavage fragments resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (C) Digitization of the gel in B. (D) Scheme of G-quartet completion by G fill-in in the GVBQ of MYOG-3332. (E) Structure of MYOG-3333 G-quadruplex. Red arrowhead in B–D indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by a G fill-in with GMP in MYOG-3332.

The effect of GMP on G-quadruplex formation was analyzed by dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprinting (20) (Fig. 2 B and C), in which guanine residues in a G-quadruplex were protected from methylation and subsequent cleavage by the Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds at the N7s (Fig. 1B). DNAs in Li+ solution without PEG were used as structure-less references because PEG can promote G-quadruplex formation under salt-deficient conditions (21). It was anticipated that the Gs in a G tract would be better protected in K+ than in Li+ solution. In principle, the MYOG-2332, with a G2-G3-G3-G2 arrangement of G tracts, is able to form a G-quadruplex of two G-quartet layers. In agreement with this, greater protection to two Gs in each G tract was observed in K+ than in Li+ solution, with an exception that the first G in the G3 tract immediately downstream of the first G2 tract from the 5′ end was heavily cleaved in K+ solution with a magnitude greater than that in the Li+ solution (Fig. 2C, Top, red arrowhead). Previous studies showed that such hyper-cleavages could occur at the Gs in the terminal G-quartet of a G-quadruplex, and the reason for that was not clear (22). Addition of GMP to the DNA did not alter the cleavage (blue vs. green peak).

For the MYOG-3332, which had a G3-G3-G3-G2 arrangement, the two G3 tracts in the middle of the sequence were well protected in K+ solution without GMP (Fig. 2C, Middle, green curve). Like the MYOG-2332, hyper-cleavage was also observed at the last G in the first G3 tract from the 5′ end (Fig. 2C, Middle, red arrowhead). Given the parallel folding topology of this DNA suggested by the CD spectrum (Fig. 2A), a preferable structure was deduced to fit this particular protection pattern (Fig. 2D, left scheme). This structure consisted of two intact G-quartets and one G-vacancy–bearing G-quartet or G-triad in which two guanine residues would be protected by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds and one be exposed to cleavage (Fig. 1C). The hyper-cleaved G became protected once GMP was added (blue vs. green peak), suggesting that the exposed N7 formed a Hoogsteen hydrogen bond. This fact implied that the G-vacancy was filled up with a guanine from GMP, resulting in an intact G-quartet to protect the G in the G-triad (Fig. 2D, right scheme). Such a G fill-in made the DMS profile of MYOG-3332 with GMP resemble that of the MYOG-3333. In the MYOG-3333, a G-vacancy was not present or, in other word, was filled up by an endogenous guanine (Fig. 2E); therefore, no hyper-cleavage and corresponding protection were seen in the absence or presence of GMP (Fig. 2C, Bottom). We also analyzed another set of DNAs derived from the HIF1α (hypoxia inducible factor 1, alpha subunit) gene (Fig. 3) that had a reversed G-tract arrangement of G2-G3-G3-G3 and different loops. Similar results were obtained with respect to the CD spectrum, hyper-cleavage, and its protection by G fill-in. In both sets of DNA, the protection mediated by G fill-in was G-vacancy specific because it was not seen with the 3-3-3-3 G tract arrangement (Figs. 2C and 3C, Bottom). The protection was also G-quadruplex specific because protection was not seen for the orphan G (black arrowhead in Fig. 3B, lane 5, and 3C, Middle).

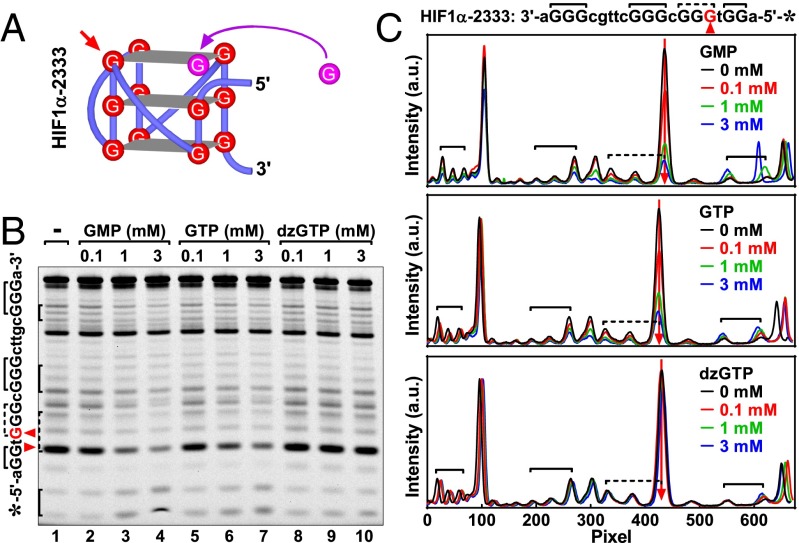

Fig. 3.

G-quadruplex formation in HIF1α G-core ssDNAs detected by (A) CD spectroscopy and (B and C) DMS footprinting. (A) CD spectra of HIF1α-2333 G-quadruplexes. (B) DNA cleavage fragments resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (C) Digitization of the gel in B. (D) Scheme of G-quartet completion by G fill-in in the GVBQ of HIF1α-2333. (E) Structure of HIF1α-3333 G-quadruplex. Red arrowhead in B–D indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by a G fill-in with GMP in HIF1α-2333. Black arrowhead indicates the orphan guanine that was not assembled in the G-quadruplex and hence not protected by GMP from cleavage in the HIF1α-2333 (blue vs. green peak).

G Fill-In Requires N7 and Depends on Guanine Derivative Concentration and Charge.

We further compared 7-deaza-GTP (dzGTP), GTP, and GMP for their ability to fill-in the G-vacancy in the GVBQ of the MYOG-3332, which was assessed by the protection to the corresponding G residue prone to hyper-cleavage (Fig. 4A, red arrow) in DMS footprinting. With its N7 being replaced by a carbon, dzGTP is unable to form a Hoogsteen hydrogen bond; as a result, dzGTP brought little protection to the hyper-cleavage (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–4; 4C, Top, red arrow). With a N7, G fill-in was detected with both GTP and GMP as judged from the suppression of the hyper-cleavage (Fig. 4B, lanes 5–12, and 4C, Middle and Bottom, red arrow). The protection to the hyper-cleaved G with GTP/GMP and the requirement of the N7 in the GTP implied that the interaction of a guanine derivative with the GVBQ involved a formation of a Hoogsteen hydrogen bond, which could only be implemented by a G fill-in at the G-vacancy.

Fig. 4.

Protection of the hyper-cleave prone guanine in the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 by G fill-in with different guanine derivatives in DMS footprinting. (A) Structure of the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 with a G fill-in (B) DNA cleavage fragments resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (C) Digitization of the gel in B. Red arrowhead indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by G fill-in with a guanine derivative.

Similar protection to the hyper-cleavage and a requirement of N7 was also observed for the HIF1α-2333 DNA (Fig. 5). For both MYOG-3332 and HIF1α-2333, the protection was concentration dependent, with a higher concentration leading to greater protection (Figs. 4 and 5 and Fig. S2). The G fill-in had to overcome the repulsion between the negative charges in the DNA and GTP/GMP. In correlation with this, a better protection was seen with GMP than with GTP.

Fig. 5.

Protection of the hyper-cleave-prone guanine in the GVBQ of HIF1α-2333 by G fill-in with different guanine derivatives in DMS footprinting. (A) Structure of the GVBQ of HIF1α-2333 with a G fill-in. (B) DNA cleavage fragments resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (C) Digitization of the gel in B. Red arrowhead indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by G-fill-in with a guanine derivative.

Fig. S2.

Quantitation of protection of hyper-cleavages in (A and B) MYOG-3332 and (C and D) HIF1α-2333 by GTP and GMP. Guanine hyper-cleavage in DMS footprinting was assayed as in Figs. 4 and 5. Intensity ratio of the hyper-cleavage (HC) band over full-length (FL) band (top band on gel) with SD was obtained from three independent experiments.

G Fill-In Stabilizes GVBQs.

G-quadruplexes of two G-quartets are much less stable than those of three G-quartets (19). We examined the thermal stability of the structures formed by the MYOG DNAs (Fig. 6A) by thermal melting monitored by FRET (23) in 50 mM K+ solution. Among them, the two G-quartet G-quadruplex formed by MYOG-2332 showed the lowest stability with a T1/2 of 51 °C. On the other hand, the G-quadruplex of three G-quartets formed by MYOG-3333 was too stable, such that a top plateau could not be obtained in the melting curve and so was the T1/2. For this reason, we lowered the K+ to 1 mM and obtained an intact melting curve, which yielded a T1/2 of 78 °C. With an additional G-triad at one side of a two G-quartet G-quadruplex, the GVBQs of MYOG-3332 showed stability (T1/2 = 68 °C) between that of the MYOG-2332 and MYOG-3333.

Fig. 6.

G fill-in stabilized the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 in FRET melting. (A) Melting of MYOG GVBQ in the absence of guanine derivatives. Curves were obtained in a solution containing 50 mM K+ (solid) or in 1 mM K+ plus 49 mM Li+ (dashed). T1/2 gives the temperature for the fluorescence to reach the midvalue between the minimum and maximum values. (B) Effect of guanine derivatives on the T1/2 of G-quadruplex from MYOG-2332, MYOG-2333, and MYOG-3333. Assay was carried out in a solution containing 1 mM K+ plus 49 mM Li+ for MYOG-3333 and 50 mM K+ for the others at various concentrations of guanine derivatives.

Completion of an intact G-quartet by G fill-in enhanced the stability of the MYOG-3332 GVBQ in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). GTP and GMP at 5 mM enhanced the T1/2 of the GVBQ by 3 and 5 °C, respectively (Table S1). A smaller increment in the T1/2 for the GTP than for the GMP reflected a charge dependence, which was fully in agreement with the protection to the hyper-cleaved guanine in the DMS footprinting (Fig. 4). dzGTP failed to stabilize the MYOG-3332 GVBQ because of its inability to form the required Hoogsteen hydrogen bond in the G fill-in. Again the G-vacancy dependence was also indicated by the fact that the G-quadruplex of MYOG-3333 was not stabilized by the two compounds. Similarly, the GVBQ formed by the HIF1α-2333 was also stabilized by GMP and GTP but not by dzGTP (Fig. S3A).

Table S1.

Increase in T1/2 (°C) of G-quadruplexes induced by 5 mM GMP or GTP in the absence or presence of 2 mM Mg2+

| Condition | MYOG-3332 | LRRC42 | ABTB2 | TSC22D3 | HIF1α-2333 |

| GMP | 5 | 7 | 12 | 10 | 7 |

| GTP | 3 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 5 |

| GMP + Mg2+ | 10 | ND | ND | 12 | ND |

| GTP + Mg2+ | 10 | ND | ND | 10 | ND |

ND, not determined.

Fig. S3.

G fill-in enhanced the stability of the GVBQ of (A) HIF1α-2333, (B) LRRC42, (C) ABTB2, and (D) TSC22D3 in FRET melting. Assay was carried out in a solution containing 50 mM K+ at various concentrations of guanine derivatives as in Fig. 6B. T1/2 indicates the temperature for the fluorescence to reach midvalue between the minimum and maximum values.

Confirmation of G Fill-In in GVBQ by Photo-Cross-Linking.

The requirement of G-vacancy and Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding in our aforementioned results strongly supported a G fill-in in the G-triad-to-G-quartet conversion. To further confirm this, we synthesized a trifunctional compound sulfosuccinimidyl-2-[6-(biotinamido)-2-(p-azidobenzamido) hexanoamido]ethyl-1,3′-dithiopropionate (SBED)-GMP (Fig. 7A and Fig. S4). The molecule carried a guanine base that can fill-in a G-vacancy, a phenyl azide group that can react with the primary amine in adenine, guanine, and cytosine to covalently cross-link a DNA, and a biotin moiety that can bind a streptavidin. We incubated the three MYOG DNAs separately with the SBED-GMP and induced cross-linking by UV light. The DNAs were then resolved by denaturing electrophoresis. Cross-linking occurred in the MYOG-3332 as indicated by an extra band migrating behind the original DNA (Fig. 7B, lane 6). In contrast, little cross-linking was seen in the other two DNAs. Because the SBED-GMP had a biotin, the cross-linked MYOG-3332 could be further shifted by streptavidin in a native gel electrophoresis (Fig. 7C, lane 6). These results therefore confirmed the G fill-in in the GVBQ of MYOG-3332. Cross-linking and mobility shift was also observed with the HIF1α-2333 GVBQ (Fig. S5).

Fig. 7.

Confirmation of G fill-in in the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 by photo-cross-linking and subsequent electrophoretic mobility shift. (A) Trifunctional SBED-GMP used for cross-linking. (B) Cross-linking between SBED-GMP and MYOG-3332 DNA detected by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (C) Mobility shift of cross-linked MYOG-3332 DNA by streptavidin (SA) detected by native gel electrophoresis. Schemes at the left side of gel indicate the structure of the corresponding DNA bands. Open triangle indicates cross-linked DNA.

Fig. S4.

(A) Synthesis of SBED-GMP from Sulfo-SBED and 5′-amino-GMP and full MS scan of the synthesized SBED-GMP. m/z 1,125.4 represents the precursor ion of SBED-GMP. Sulfo-SBED reacts with the amine (-NH2) residue on 5′-amino-GMP, resulting in a trifunctional SBED-GMP. (B) Mass spectrum of the fragment ions of SBED-GMP.

Fig. S5.

Confirmation of G fill-in the GVBQ of HIF1α-2333 by photo-cross-linking and subsequent electrophoretic mobility shift. (A) Cross-linking between SBED-GMP and HIF1α-2333 DNA detected by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (B) Mobility shift of cross-linked HIF1α-2333 DNA by streptavidin (SA) detected by native gel electrophoresis. Schemes at the left side of gel indicate the structure of the corresponding DNA bands. Open triangle indicates cross-linked DNA.

GVBQ Formation, G Fill-In, and Stability Enhancement in Other G2/3G3 Combinations.

Our aforementioned results used DNA with a G3-G3-G3-G2 or G2-G3-G3-G3 G-tract arrangement. In general, the G2 tract can be placed at four different positions. To find out the generality of G fill-in, we tested three additional native sequences from human genes, namely, LRRC42 (leucine rich repeat containing 42), ABTB2 [ankyrin repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 2], and TSC22D3 (TSC22 domain family, member 3), which had an arrangement of G3-G3-G2-G3, G3-G2-G3-G3 and G2-G3-G3-G3, respectively (Fig. S1). Similar to the MYOG-3332, the three DNAs all featured a positive peak at 265 nm and a negative peak at 245 nm in their CD spectrum, suggesting they formed parallel G-quadruplexes (Fig. S6A).

Fig. S6.

Formation of GVBQ in LRRC42, ABTB2, and TSC22D3 ssDNA detected by (A) CD spectroscopy and (B–G) DMS footprinting. (B–D) DNA was incubated in a solution containing 50 mM of the indicated cation in the absence or presence of GMP before DMS treatment. (E–G) Digitization of the gels in B–D). Schemes at the right side of E–G indicate the structure of the G-quadruplexes based on the CD and footprinting results. Red arrowhead indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by a G fill-in with GMP. Black arrowhead indicates the orphan guanine that was not assembled in the G-quadruplex and hence not protected by GMP from cleavage (blue vs. green peak).

In DMS footprinting, the G tracts in all DNAs were better protected in K+ than in Li+ solution (Fig. S6 B–G), except the hyper-cleavage in the G3 immediately downstream of the G2 tract as we saw in the MYOG-3332. Unlike the MYOG-3332, which showed only one hyper-cleavage peak, the LRRC42 and ABTB2 displayed two hyper-cleavage peaks at both the 5′ and 3′ G in the G3 tract, which were all prevented by GMP (Fig. S6 B, C, E, and F, red arrowhead). This particular cleavage/protection pattern could be explained by an alternative G fill-in to the two ends of the G3 tract (schemes on the right side of the panels). In TSC22D3, the cleavage/protection more or less resembled that in the MYOG-3332 in that the Gs in the G tracts were all protected except the first G in the G3 tract immediately downstream of the G2 tract (Fig. S6 D and G, red arrowhead). The hyper-cleavage seems to be a common feature in all of the DNAs, implying that the unprotected guanine in the G-triad (Fig. 1C, red circle) was highly exposed to chemical attack in the DMS footprinting and rescued by the G fill-in. Again, the orphan Gs was not protected in the three DNAs (Fig. S6 B–G, black arrowhead), further confirming that the G fill-in was specific to G-vacancy.

The GVBQs formed in these DNAs were also stabilized by a G fill-in with GTP and GMP (Fig. S3 B–D). At 5 mM, GMP led to an increment in T1/2 of 7, 12, and 10 °C, respectively, for LRRC42, ABTB2, and TSC22D3, whereas GTP was less effective. Similarly, dzGTP failed to stabilize any GVBQ, indicating a requirement of Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding. For comparison, the melting data were summarized in Table S1. Again, the G fill-in for the three DNAs was also confirmed by cross-linking with SBED-GMP and subsequent mobility shift with streptavidin (Fig. S7).

Fig. S7.

Confirmation of G fill-in in the GVBQ of LRRC42, ABTB2, and TSC22D3 by photo-cross-linking and subsequent electrophoretic mobility shift. (A) Cross-linking between SBED-GMP and DNAs detected by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (B) Mobility shift of cross-linked DNA by streptavidin (SA) detected by native gel electrophoresis. Schemes at the left side of gel indicate the structure of the corresponding DNA bands. Open triangle indicates cross-linked DNA.

GVBQ Formation and G Fill-In in G2/3G3 ssDNA in Solution Without PEG.

Our aforementioned experiments were carried out in a K+ solution containing PEG. PEG stabilizes G-quadruplexes (21, 24), thus benefiting their detection in vitro. We also assessed the formation of GVBQs and G fill-in in PEG-free K+ solution. CD spectroscopy showed that MYOG-3332, LRRC42, ABTB2, and TSC22D3 ssDNA might all form parallel G-quadruplexes (Fig. S8A). In DMS footprinting, the four DNAs all displayed hyper-cleavage and protection pattern (Fig. S8 B–F) similar to those obtained in the K+ solution containing PEG (Figs. 2C and 3C and Fig. S6 E–G). G fill-in was also detected by photo-cross-linking and mobility shift with SBED-GMP (Fig. S8G). All these results showed that the formation of GVBQ and G fill-in also occurred in the absence of PEG.

Fig. S8.

(A) Formation of GVBQ in MYOG-3332, LRRC42, ABTB2, and TSC22D3 ssDNA detected by (A) CD spectroscopy, (B–F) DMS footprinting, and (G) photo-cross-linking and electrophoretic mobility shift with streptavidin (SA). (A) CD spectra were obtained in a solution containing 150 mM K+ without PEG. (B–F) DNA was incubated in a solution containing 150 mM of the indicated cation in the absence or presence of GMP without PEG before DMS treatment. Red arrowhead indicates hyper-cleaved guanine residue that was protected by a G fill-in with GMP. (G) DNA was incubated in a solution containing 150 mM K+ without PEG before cross-linking. Open triangle indicates cross-linked DNA.

G-Quadruplex Formation in Transcribed G2/3G3 dsDNA.

Here we show that GVBQ can also form in dsDNA in transcription. Three dsDNAs containing the MYOG-3332, MYOG-2332, and MYOG-3333 G-core were transcribed in the presence of dzGTP, GTP, and GMP. G-quadruplex formation was analyzed by DMS footprinting. For the MYOG-2332 (Fig. 8A, lanes 1–4), transcriptions in the presence of different guanine derivatives all led to a protection to two Gs in each G tract (Fig. 8B, Top), indicating that G-quadruplexes of two G-quartets formed. For the MYOG-3332 (Fig. 8A, lanes 5–8), transcription with dzGTP resulted in a protection to only two Gs in each G3 tract (Fig. 8B, Middle). Because dzGTP lacked the N7 and thus prevented the RNA transcript from forming G-quadruplex, the protection pattern indicated that an intramolecular DNA G-quadruplex of two G-quartets formed (Fig. 8C, left scheme). However, when we supplied GMP with dzGTP or conducted the transcription with GTP and GMP, the previously cleaved Gs in each G3 tract became protected. The magnitude of protection in these two cases was similar to but less than that to the G3 tracts in the MYOG-3333 (Fig. 8B, Bottom), which was capable of forming a G-quadruplex of three intact G-quartets.

Fig. 8.

G-quadruplex formation in transcribed MYOG dsDNAs detected by DMS footprinting. (A) DNA cleavage fragments resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis. (B) Digitization of the gel in A. (C) Possible alternative G2 tract alignment that could lead to G3 tracts protection. (D) G fill-in at the G-vacancy by GMP/GTP that could lead to G3 tracts protection. DNA was not transcribed (NT) or transcribed in the presence of the indicated guanine derivative(s). Red arrowhead in B–D indicates the guanine residue attacked in the absence and protected in the presence of GMP/GTP. Blue curves in B largely overlap with the green ones such that they are barely visible.

The protection of all of the Gs in the G3 tracts in the MYOG-3332 brought by GMP/GTP suggested a formation of new forms of G-quadruplexes in which all of the Gs in all of the G3 tracts participated in G-quadruplex assembly. In principle, there were two possibilities. First, the new G-quadruplexes might involve an alternative alignment of the G2 to the 5′ or 3′ side of the G3 tracts (Fig. 8C). However, it is difficult to imagine how GMP/GTP in solution would drive such a change in the alignment. The fact that the protection was seen with GMP/GTP and not with dzGTP implied formation of a Hoogsteen hydrogen bond at the N7 was required for the protection. Given this, then a plausible interpretation would be a formation of GVBQ of three G-quartets with a G-vacancy in a terminal G-quartet (Fig. 8D, center scheme). The guanine base from GMP or GTP then filled up the G-vacancy to complete a G-quartet (Fig. 8D, right scheme), and thus, protect all of the Gs in the G3 tracts from cleavage. dzGTP failed to do so because it lacked the N7 to form the required Hoogsteen hydrogen bond in the G-quartet.

Effect of GVBQ and G Fill-In on in Vitro DNA Replication.

We examined the effect of GVBQ stabilization by GMP/GTP on an in vitro DNA replication in which primer extension was catalyzed by DNA polymerase through a GVBQ-containing DNA template. The GVBQ caused premature termination (PT) of replication, which was significantly enhanced by both GMP and GTP (Fig. 9 A and B). For MYOG-3332, the PT at the GVBQ increased by more than threefold at 1 mM GMP/GTP. Because GMP/GTP at 1 mM increased the T1/2 of the MYOG-3332 GVBQ by only 1–2 °C (Fig. 6B), we reasoned that the interaction between the GVBQ and GMP/GTP might be reinforced by the Mg2+ in the reaction buffer. Indeed, a more dramatic increase in the T1/2 of the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 and TSC22D3 was observed in the presence of physiological concentration of 2 mM Mg2+ (25, 26) (Fig. 9C). Particularly, GTP became as effective as GMP in stabilizing the GVBQs. The effect of GMP/GTP was GVBQ specific because they had little effect on the random DNA without a GVBQ and MYOG-3332 and TSC22D3 when they were replicated in Li+ solution that does not stabilize G-quadruplex (Fig. 9A). We attempted to examine the effect of GVBQ on in vitro transcription by T7 RNA polymerase but did not succeed because efficient RNA synthesis requires starting with a guanine residue such that GMP or GTP had to be used in all samples.

Fig. 9.

Effect of G fill-in in GVBQ on in vitro DNA replication and stability in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+. (A) Inhibition of DNA primer extension by stabilization of GVBQ of MYOG-3332 and TSC22D3 with GMP/GTP, assayed by DNA-templated primer extension. Marker was made by a same extension reaction with a template without the G-core and its 3′ flanking sequence. (B) Ratio of premature termination (PT) over full-length (FL) replicon (±SD) in three independent experiments in K+ solution demonstrated in A. (C) Stabilization of the GVBQ of MYOG-3332 and TSC22D3 as a function of GMP/GTP concentration assayed by FRET melting.

Occurrence of GVBQ-Forming Motifs in Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Genes.

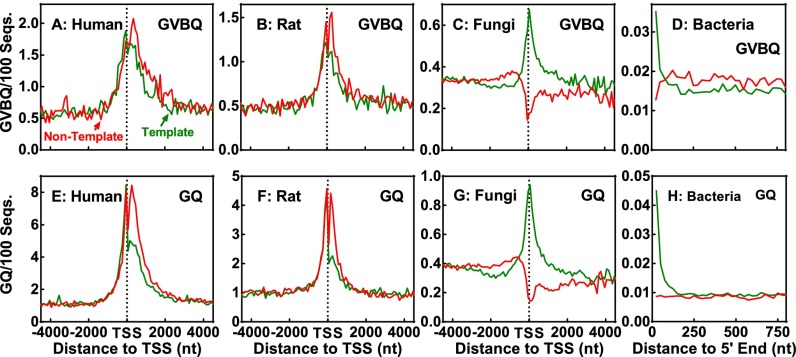

To seek information regarding the potential formation and function of GVBQ in cells, we conducted bioinformatic surveys on the distribution of GVBQ-forming motifs in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic genes. The results show that such motifs are enriched near the transcription start site (TSS) in mammalian genes (Fig. 10 A and B), suggesting that GVBQ may form and play a functional role in cells. A survey of the whole human genome (hg19) found a total of ∼220,000 potential GVBQ-forming motifs with a G-tract combination of G2/3G3–4, which is in the same order of that of the canonical G-quadruplex forming motifs (360,000) found in this survey.

Fig. 10.

Distribution of potential GVBQ-forming motifs in comparison with the canonical G-quadruplex–forming sequences (GQ) in prokaryotic and eukaryotic genes. Motifs bearing one G2 and three G3–4 tracts, with loop sizes from one to seven nucleotides, are counted on both the nontemplate (red) and template (green) DNA strands. Survey on fungi and bacteria covered genes from 53 strains and 4,222 chromosomes, respectively, whose sequences were available in the Ensembl and NCBI database. Frequency was normalized to the number of sequences and expressed as the number of occurrences in 100 sequences in a 100- (human, rat, and fungi) or 25-nt (bacteria) window.

Although a survey on a single lower species, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, did not result in a clear occurrence pattern (27) because of limited number of genes, we were able to obtain one when 53 fungi species available in the Ensembl genome database, including S. cerevisiae, were analyzed. The results showed a positive selection of GVBQ-forming motifs on the template DNA strand and a small negative selection on the nontemplate DNA strand around TSS (Fig. 10C). Because TSS coordinates are not available for bacteria, we only surveyed within bacteria genes. The results from 4,222 chromosomes available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database showed a strong positive selection of such motifs on the template DNA strand near the 5′ end of genes, but not on the nontemplate DNA strand (Fig. 10D). The distribution of GVBQ-forming motifs in all of the analyzed organisms closely resembled that of the canonical G-quadruplexes (Fig. 10 E–H) except in a lower frequency. All these results are supportive of the existence and functional role of GVBQs in the eukaryotic and prokaryotic kingdoms.

Discussion

In this work, we found a different type of intramolecular G-quadruplexes that can form in sequences not following the consensus of G≥3(N1–7G≥3)≥3. Using one G2 and three G3 tracts, the G-quadruplexes contained a G-triad layer or, in other words, an incomplete G-quartet with a G-vacancy at one corner. The G-vacancy can be filled up by a guanine base when it is available from solution to complete a G-quartet. The G fill-in was indicated by the requirement of N7 in the guanine base needed for the formation of a Hoogsteen hydrogen bond in a G-quartet, supported by protection to guanine hyper-cleavage and G-quadruplex stabilization, and further confirmed by photo-cross-linking, all in a G-vacancy– and N7-dependent manner. This finding expands not only the possibility of G-quadruplex formation in guanine-rich nucleic acids, but also the structural diversity of G-quadruplexes.

One unique characteristic of the GVBQs distinctive from the canonical G-quadruplexes is their capability to interact with guanine derivatives. By a G fill-in of a G-vacancy, the G-quartet completion doubles the number of Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds from 4 to 8 in the G-quartet (Fig. 1C), resulting in a full stacking with the neighboring G-quartet. Therefore, the GVBQ is dramatically stabilized by GMP/GTP and the stabilization is further enhanced by physiological concentration of Mg2+. In the presence of 2 mM Mg2+, GTP is as effective as GMP in stabilizing GVBQs (Table S1) and affecting replication (Fig. 9). Guanine derivatives, such as GMP, GDP, and GTP, are natural metabolites in cells. As the most dominant species, free GTP content is ∼0.5 mM in animal (28) and ∼5 mM (29) in bacterial cells. Free Mg2+ content ranges from 0.15 to 6 mM in animal (25) and 2–3 mM in bacterial cells (26). The stability and the replication of GVBQ-containing DNA could be effectively manipulated by submillimolar and millimolar GTP (Fig. 9). This fact implies that the intracellular GTP level in both animal and bacterial cells is able to influence the stability of GVBQs and likely the related cellular processes.

The in vitro formation of GVBQ and G fill-in with physiological concentration of GTP, as well as the enrichment of GVBQ-forming motifs near the 5′ end of genes, support the formation of GVBQ in cells. The ability of the GVBQs to response to changes in the concentration of guanine derivatives suggests a possibility for the GVBQs to play environment-responsive regulation in cellular processes. On the other hand, the G fill-in may also constitute a unique pathway for drug targeting toward such regulations. Because their number in the human genome is comparable to that of the canonical G-quadruplexes, the GVBQs represent a unique category of G-quadruplex structures distinctive from the canonical G-quadruplexes.

In our current study, only G2/3G3 DNAs were used. Sequences with potential to form GVBQs may go beyond this rule. For instance, a G2 tract may combine with three G tracts with three to four consecutive guanines (G2/3G3–4). GVBQs may also form with a G tract format of Gn-1/3Gn (n ≥ 3) with n − 1 intact G-quartet layers. We also expect that a GVBQ may accommodate more than one G-vacancy when having sufficient number of intact G-quartets. These possibilities may further diversify the formation of GVBQs and their physiological implications.

Materials and Methods

Details are in SI Materials and Methods, including chemicals and oligonucleotides, preparation of DNAs, in vitro transcription, DMS footprinting, CD spectroscopy, photo-cross-linking, EMSA, thermal melting, DNA polymerase stop assay, and computational survey.

SI Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Oligonucleotides.

SBED was purchased from Thermo Scientific. 5′-Amino-GMP was purchased from Trilink Biotechnologies. Custom synthesis of SBED-GMP using Sulfo-SBED and 5′-amino-GMP was purchased from Takara Biotechnology. Oligonucleotides used in transcription and CD spectroscopy were purchased from Sangon Biotechnology. Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides were purchased from Takara Biotechnology.

Preparation of dsDNA and ssDNA.

dsDNA (5′-GGCTTCGGAGTCCCCTGCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAGACTACTCAACCTTTACAXTCTACTCTTCTTCACTCGCCGCAGGCTGG-3′, where X was GGTGGGCTGGGAGG, GGGTGGGCTGGGAGG, or GGGTGGGCTGGGAGGG) with a T7 promoter at the 5′ side was made by heating oligonucleotides at 95 °C in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 30 mM LiCl for 5 min and then cooling down to room temperature at a rate of 0.03 °C/s. For ssDNA, oligonucleotides were dissolved in 50 mM Lithium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 40% (wt/vol) PEG 200 and 50 mM KCl unless otherwise indicated, heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and then cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 0.03 °C/s.

DMS Footprinting.

Footprinting of transcribed dsDNA was performed as we described previously (17). For ssDNA, 0.1 μM oligonucleotide was incubated on ice with dzGTP, GTP, and GMP, respectively, at the indicated concentration for 15 min. The mixture was then treated with 0.2% DMS for 5 min on ice, in a 200-μL volume, and the reaction was stopped by adding 150 μL stop buffer (2.5 M NH4OAc, 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mg/mL sperm DNA). After phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the DNA was dissolved in 100 μL of 10% (vol/vol) piperidine in water. It was then heated at 90 °C for 30 min, followed by chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The precipitated DNA was dissolved in 80% (vol/vol) deionized formamide in water, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and resolved on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. DNA fragments were visualized by a FAM dye covalently labeled at their 5′ end of the DNA on a Typhoon 9400 Imager (GE Healthcare) and digitized using the ImageQuant 5.2 software.

CD Spectroscopy.

DNA (0.5 μM) was dissolved in 50 mM lithium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 40% (wt/vol) PEG 200 and 50 mM KCl, heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and then cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 0.03 °C/s. CD spectrum was collected from 320 to 220 nm at 1-nm bandwidth on a Chirascan Plus CD spectropolarimeter (Applied Photophysics) with a 10-mm path length. Buffer blank correction was made for all samples.

Thermal Melting Profiling by FRET.

Oligonucleotide labeled at the 5′ end with a fluorescent donor FAM and 3′ with an accepter TAMRA was dissolved at 0.1 μM in 50 mM lithium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mM KCl and 40% (wt/vol) PEG 200, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and slowly cooled down to 25 °C. Then GTP, GMP, or dzGTP was added at the desired concentration, and the sample was incubation on ice for 15 min in the absence or presence of 2 mM Mg2+. After an initial equilibration at 25 °C for 10 min, FRET melting was carried out as prevously described (23) by monitoring FAM fluorescence on a QuantStudio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) with the temperature increasing at a rate of 0.02 °C/s to 99 °C.

Photo-Cross-Linking.

Oligonucleotides at 0.1 μM were incubated with 0.5 mM SBED-GMP and 1 mg/mL fish sperm DNA on ice for 15 min and then transferred to a 24-well microtiter plate (Costar), placed on ice in a UVP CL-1000 UV Cross-linker (UVP), and irradiated for 30 min with 365-nm UV light at a distance of 4–5 cm. DNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation, dissolved in water, resolved on a denaturing gel, and visualized on a Typhoon 9400 Imager (GE Healthcare).

EMSA.

Two pmoles cross-linked oligonucleotides in water was mixed with 1 μg streptavidin (Promega) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a total volume of 10 μL of 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 30 mM LiCl and 1 mg/mL fish sperm DNA. The oligonucleotides were resolved on a native 16% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by the TAMRA dye covalently labeled at their 3′ end of the DNA on a Typhoon 9400 Imager (GE Healthcare).

Identification of SBED-GMP by MS.

The identification of SBED-GMP was performed on an AB 3200 QTRAP mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (Turbo Ionspray) under positive mode. The ion source parameters were as follows: nebulizer (GS1), 20 psi; curtain gas (CUR), 10 psi; ion-spray needle voltage (IS), 5000 V. The AB Sciex Analyst software package (Version 1.5) was used for the whole ESI-MS/MS system control, data acquisition and processing. Q1 scan was applied initially with declustering potential (DP) of 20 V and entrance potential of 10 V. Product ion scan of m/z 1,125.4 ([M+H]+ of SBED-GMP) was introduced to identify the fragment ion products. The collision energy of product ion scan was set at 30 eV, with a collision cell exit potential of 5 V and an entrance potential of 10 V.

DNA Polymerase Stop Assay.

The assays were carried out as previously described with modifications (30). Briefly, 0.12 μM FAM-labeled primer were mixed with 0.1 μM template DNA in 100 μL of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mM K+ and 40% (wt/vol) PEG 200, denatured by heating at 95 °C for 5 min, cooled down to 20 °C at a rate of 0.03 °C/s, and then incubated with various concentrations of GTP or GMP on ice for 15 min. Primer extension was initiated by adding 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM dTTP, dATP, dCTP, 7-deaza-dGTP (NEB) each, and 7.5 U Bsu DNA Polymerase, Large Fragment (NEB). The reactions were kept at 37 °C for 15 min and then stopped by adding 25 mM EDTA, followed by chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The precipitated DNA was dissolved in 80% (vol/vol) deionized formamide in water, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and resolved on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. DNA fragments were visualized by scanning on a Typhoon 9400 Imager (GE Healthcare) and digitized using the Image Quant 5.2 software.

Computational Survey of Motif Occurrence.

Sequences of protein-coding genes of human (GRCh38.p3), rat (Rnor_6.0), and 53 fungi strains (Release 28) crossing transcription start site (TSS) were downloaded from the Ensembl database at www.ensembl.org and fungi.ensembl.org, respectively, using the BioMart tool. GenBank files of 4,222 bacterial chromosomes were downloaded from the NCBI website (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) on 22 September 2015, and gene sequences were extracted using a home-made Perl script. Chromosome sequences (hg19) were downloaded from the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser database (ftp://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/chromosomes/). The searching of sequences with potential to form intramolecular G-quadruplexes of three G-quartets with a G-vacancy was carried out using the home-made Perl script we previously described (27) with modifications. Briefly, motifs matching G≥2(N1–7G≥2)≥3, where G denoted guanine and N any nucleotide including G, were first identified using a pattern-matching code G{2,}(.{1,7}?G{2,}){3,}. Among the identified motifs, any that had G tracts other than one G2 and three G3 or G3–4 was discarded. Tracts of G>4 were not counted because they may break into two G tracts. The searching of sequences with potential to form the canonical intramolecular G-quadruplexes was carried out using a pattern-matching code G{3,}(.{1,7}?G{3,}){3,} as previously described (27).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grants 2013CB530802 and 2012CB720601 and National Science Foundation of China Grants 31470783 and 21432008.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1516925112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S. Quadruplex DNA: Sequence, topology and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(19):5402–5415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian S, Hurley LH, Neidle S. Targeting G-quadruplexes in gene promoters: A novel anticancer strategy? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(4):261–275. doi: 10.1038/nrd3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel DJ, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V. Human telomere, oncogenic promoter and 5′-UTR G-quadruplexes: Diverse higher order DNA and RNA targets for cancer therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(22):7429–7455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarsounas M, Tijsterman M. Genomes and G-quadruplexes: For better or for worse. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(23):4782–4789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahoon LA, Seifert HS. An alternative DNA structure is necessary for pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Science. 2009;325(5941):764–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1175653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez R, et al. Small-molecule-induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(3):301–310. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray LT, Vallur AC, Eddy J, Maizels N. G quadruplexes are genomewide targets of transcriptional helicases XPB and XPD. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(4):313–318. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen GH, et al. Regulation of gene expression by the BLM helicase correlates with the presence of G-quadruplex DNA motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(27):9905–9910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404807111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd AK, Johnston M, Neidle S. Highly prevalent putative quadruplex sequence motifs in human DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(9):2901–2907. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S. Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(9):2908–2916. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal P, Lin C, Mathad RI, Carver M, Yang D. The major G-quadruplex formed in the human BCL-2 proximal promoter adopts a parallel structure with a 13-nt loop in K+ solution. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(5):1750–1753. doi: 10.1021/ja4118945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guédin A, Gros J, Alberti P, Mergny JL. How long is too long? Effects of loop size on G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(21):7858–7868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Burge S, Neidle S, Patel DJ. Structure of an unprecedented G-quadruplex scaffold in the human c-kit promoter. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(14):4386–4392. doi: 10.1021/ja068739h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, et al. The major G-quadruplex formed in the human platelet-derived growth factor receptor β promoter adopts a novel broken-strand structure in K+ solution. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(32):13220–13223. doi: 10.1021/ja305764d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukundan VT, Phan AT. Bulges in G-quadruplexes: Broadening the definition of G-quadruplex-forming sequences. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(13):5017–5028. doi: 10.1021/ja310251r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng KW, et al. A competitive formation of DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex is responsible to the mitochondrial transcription termination at the DNA replication priming site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(16):10832–10844. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng KW, et al. Co-transcriptional formation of DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex and potential function as constitutional cis element for transcription control. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(10):5533–5541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu RY, Zheng KW, Zhang JY, Hao YH, Tan Z. Formation of DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex in bacterial cells and its dominance over the intramolecular DNA G-quadruplex in mediating transcription termination. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(8):2447–2451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao S, et al. Formation of DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplexes of two G-quartet layers in transcription: Expansion of the prevalence and diversity of G-quadruplexes in genomes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(48):13110–13114. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun D, Hurley LH. Biochemical techniques for the characterization of G-quadruplex structures: EMSA, DMS footprinting, and DNA polymerase stop assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;608:65–79. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-363-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kan ZY, et al. Molecular crowding induces telomere G-quadruplex formation under salt-deficient conditions and enhances its competition with duplex formation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(10):1629–1632. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo K, Gokhale V, Hurley LH, Sun D. Intramolecularly folded G-quadruplex and i-motif structures in the proximal promoter of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(14):4598–4608. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Cian A, et al. Fluorescence-based melting assays for studying quadruplex ligands. Methods. 2007;42(2):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng KW, Chen Z, Hao YH, Tan Z. Molecular crowding creates an essential environment for the formation of stable G-quadruplexes in long double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(1):327–338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romani A, Scarpa A. Regulation of cell magnesium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90086-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cayley S, Lewis BA, Guttman HJ, Record MT., Jr Characterization of the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli K-12 as a function of external osmolarity. Implications for protein-DNA interactions in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1991;222(2):281–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90212-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao S, Zhang JY, Zheng KW, Hao YH, Tan Z. Bioinformatic analysis reveals an evolutional selection for DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex structures as putative transcription regulatory elements in warm-blooded animals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(22):10379–10390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traut TW. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;140(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00928361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett BD, et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(8):593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han H, Hurley LH, Salazar M. A DNA polymerase stop assay for G-quadruplex-interactive compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):537–542. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]