Significance

A large number of genetic alterations have been found in the cancer genome of lung adenocarcinoma. However, they need experimental validation to determine their tumorigenic potential, as well as the therapeutic utility of individual alterations. Here, we provide an shRNA-mediated screen to validate a large set of genes for their tumor suppressor efficacy in vivo in a mouse lung adenocarcinoma model. We identified several tumor suppressors, including ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2) loss of which promotes adenocarcinoma in the context of oncogenic mutant KRas mutation. EphA2 loss promotes cell proliferation by activating ERK MAP kinase signaling and hedgehog signaling pathways, leading to tumorigenesis. Identification of these pathways provides important therapeutic targets for lung adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: lung adenocarcinoma, KrasG12D, in vivo shRNA screen, EphA2, Hedgehog signaling

Abstract

Lung adenocarcinoma, a major form of non-small cell lung cancer, is the leading cause of cancer deaths. The Cancer Genome Atlas analysis of lung adenocarcinoma has identified a large number of previously unknown copy number alterations and mutations, requiring experimental validation before use in therapeutics. Here, we describe an shRNA-mediated high-throughput approach to test a set of genes for their ability to function as tumor suppressors in the background of mutant KRas and WT Tp53. We identified several candidate genes from tumors originated from lentiviral delivery of shRNAs along with Cre recombinase into lungs of Loxp-stop-Loxp-KRas mice. Ephrin receptorA2 (EphA2) is among the top candidate genes and was reconfirmed by two distinct shRNAs. By generating knockdown, inducible knockdown and knockout cell lines for loss of EphA2, we showed that negating its expression activates a transcriptional program for cell proliferation. Loss of EPHA2 releases feedback inhibition of KRAS, resulting in activation of ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling, leading to enhanced cell proliferation. Intriguingly, loss of EPHA2 induces activation of GLI1 transcription factor and hedgehog signaling that further contributes to cell proliferation. Small molecules targeting MEK1/2 and Smoothened hamper proliferation in EphA2-deficient cells. Additionally, in EphA2 WT cells, activation of EPHA2 by its ligand, EFNA1, affects KRAS–RAF interaction, leading to inhibition of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and cell proliferation. Together, our studies have identified that (i) EphA2 acts as a KRas cooperative tumor suppressor by in vivo screen and (ii) reactivation of the EphA2 signal may serve as a potential therapeutic for KRas-induced human lung cancers.

Lung cancer is a lethal disease causing the most cancer-related mortalities (1). Comprehensive genomic analysis of lung adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer, revealed mutations, copy number variations, and altered transcriptional profiles of both known tumor-causing genes and a large number of previously unknown alterations (2–4). These gene alterations result in loss or gain of function affecting key pathways, including cell survival, proliferation, stemness, angiogenesis, etc. (2–4). Among these pathways were receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/RAS/RAF pathway activation, PI3-kinase–mTOR pathway activation, p53 pathway mutations, alterations of cell cycle regulators, alterations of oxidative stress pathways, and mutations of various chromatin and RNA splicing factors (2). Even though several of the known oncogenes have been characterized for their role in tumorigenesis using mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma (5–7), large numbers of alterations have not yet been experimentally validated. It is essential to characterize the role of novel genetic alterations to explore their potential therapeutic value. High-throughput screens in vivo are pivotal to determine tumorigenicity of genes although these screens have been largely limited to orthotopic or s.c. xenograft models using cultured cells (8–10). In vivo high-throughput approaches to determine the oncogenic potential of genes have been performed using transposon-mediated mutagenesis (11–13). Direct in vivo shRNA screens using lentiviral injections in embryonic skin cells identified several potential tumorigenic factors (14–16). None of the reported studies have performed direct shRNA-mediated high-throughput approaches in adult mice recapitulating the mode of tumorigenesis in humans.

Activating mutations at positions 12, 13, and 61 amino acids in Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRas) contributes to tumorigenesis in 32% of lung adenocarcinoma patients (2) by activating downstream signaling cascades. Mice with the KRasG12D allele develop benign adenomatous lesions with long latency to develop adenocarcinoma (17, 18). A combination of Tp53 deletion and KRasG12D activation leads to significant reduction in latency and generates aggressive lung adenocarcinoma (7, 18, 19). Further, KRasG12D cooperates with deletion of other tumor suppressors (5) to develop lung adenocarcinoma, such as Lkb1 (20), Pten (21), and P19Arf (22) in genetic mouse models. However, cancer genomic studies have discovered a large number of unknown mutations or copy number alterations that coexisted with KRAS mutations in human patients, and experimental validation of all of the other mutations or copy number alterations by conventional genetic mouse models would be arduous. In this report, we implement a direct in vivo shRNA screen in KRasG12D mice to validate a set of signal transduction genes for their function as tumor suppressors in developing lung adenocarcinoma.

Ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2) was one of the genes we found from our approach that accelerates KRasG12D-mediated lung adenocarcinoma. EphA2 belongs to the Ephrin receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinases that bind to cell surface ephrin ligands and initiate a relay of signal transduction events bidirectionally from both receptor and ligand (23). Binding of Ephrin A1 (EFNA1) to EPHA2 results in phosphorylation of EPHA2 and activation of a downstream signaling cascade that regulates various cellular processes, including cell shape, movement, angiogenesis, survival, and proliferation (23, 24). In cancer, EphA2 has been reported to be both tumor-promoting and tumor-inhibiting although a large amount of evidence points to its tumor suppressor activity (23, 24). EphA2 knockout mice were shown to be very susceptible to DMBA/TPA-induced skin carcinogenesis (25). Further, activation of EPHA2 by its ligand EFNA1 or small molecule induced activation of EPHA2 reduces cell proliferation and cell motility and suppresses integrin function, suggesting its tumor-suppressive function (26–28). Our high-throughput approach identified EphA2 as a prime tumor suppressor candidate, and we hypothesized that, if deleted in a tumor cell-specific manner, EphA2 would function as a KRasG12D-cooperative tumor suppressor in lung adenocarcinoma. Loss of EphA2 enhances cell proliferation by activating the ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling pathway that leads to release of EPHA2-mediated feedback inhibition. Furthermore, we show that Gli transcription factor and Hedgehog signaling are activated in cells that are deficient for EphA2, contributing to cell proliferation. We also show that ligand-activated EPHA2 affects RAS–RAF interaction and inhibits the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and cell proliferation.

Results

An in Vivo shRNA High-Throughput Approach to Identify KRasG12D Cooperative Tumor Suppressors.

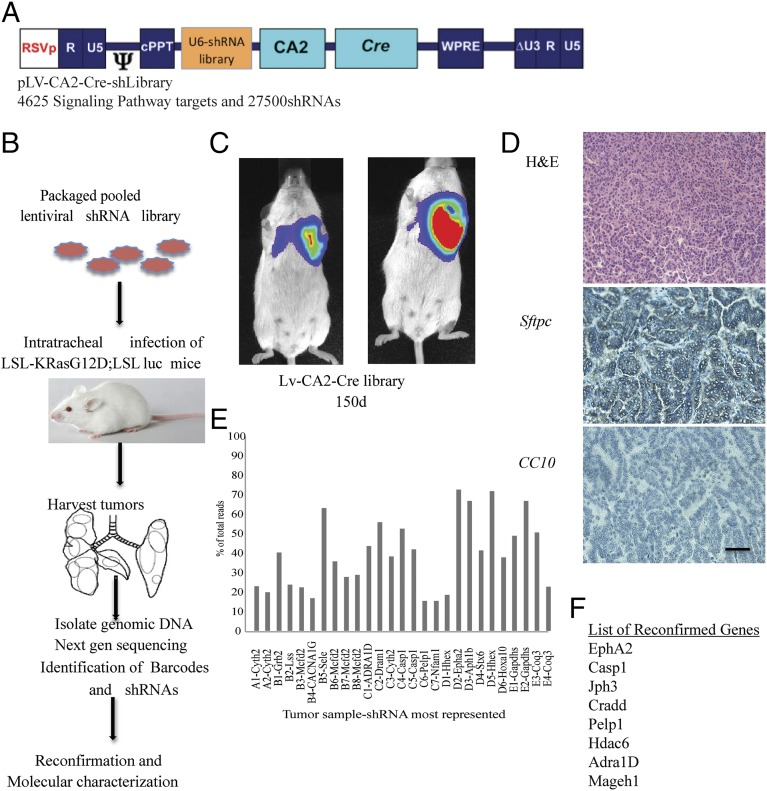

We have previously developed a mouse model of lung cancer by lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase, activating the KRasG12D mutant allele in Loxp-Stop-Loxp-KRasG12D (LSL-KRas) mice in a lung epithelium-specific manner (18). These mice also contain the LSL-luciferase allele and express Cre-dependent luciferase expression. The intratracheal instillation of the CA2-Cre lentivirus, at a dose of 105 lentiviral particles, into LSL-KRas mice generated adenomas and adenocarcinoma with a latency of up to 12 mo (Fig. S1A) (17, 18). When combined with knockdown of Tp53 by shRNA (pLV-CA2-Cre-shP53), generation of lung adenocarcinoma was significantly accelerated (3–4 mo) and led to decreased survival (4–6 mo) (Fig. S1A). Owing to the long latency in KRasG12D activation-dependent development of lung adenocarcinoma, we hypothesized that using an shRNA-mediated high-throughput approach in LSL-KRas mice using a shRNA library might identify putative tumor suppressors in the context of KRasG12D activation (Fig. 1 A and B). Knockdown of the targeted genes would cooperate with KRasG12D and accelerate generation of lung adenocarcinoma analogous to TP53 shRNA, but in the Tp53 WT genetic background. A pooled lentiviral library (pLV-CA2-Cre-shLibrary) of shRNAs targeting 4,725 signal transduction genes was generated using the lenti-CA2-Cre vector. Each gene was targeted by 5–6 shRNAs, and the library comprised ∼27,000 shRNA vectors (Fig. 1A). Pooled lentivirus was intratracheally transduced into LSL-KRas mice. Bioluminescent imaging revealed development of several tumors as early as 4–7 mo (Fig. 1C). Histologically, these tumors exhibit typical features of adenocarcinoma (H&E), with surfactin staining (prosurfactant protein C) positive and CC10 (Clara cell-specific antigen) negative staining patterns (Fig. 1D). To investigate shRNA representation in tumors in comparison with the original library and in early stages of infection in tumor-initiating cells, deep sequencing and identification of barcodes were performed. Samples from the input plasmid library, transduced 293T cells, samples from lungs of the second day or tenth day after infection in mice, and tumor nodules that are generated 4–7 mo postinfection were deep sequenced to identify barcodes. Comparisons of overall distributions of all detected shRNAs from all samples showed samples clustered tightly with each other and the plasmid (Fig. S1B). The library representation in transduced 293T cells and second day-infected lungs was nearly equal to the input plasmid library (Fig. S1C). Ten days postinfection, the library representation was reduced to 70–80% of the input library. In the endpoint tumors, only 5–15% of the total shRNAs were detected. The list of all shRNAs that are represented in each tumor is shown in Dataset S1. Analysis of genes that are targeted by different shRNA (Fig. S1D) shows that 68 genes were represented by two shRNAs and 3 genes were represented by three shRNAs. Some shRNAs are represented in more than one tumor, and multiple occurrences of each shRNA are presented in Fig. S1E. Fig. S1F shows the pie chart of shRNAs that are detected in independent tumor nodules. The genes that were targeted by the shRNAs were prioritized based on (i) whether the barcodes for particular shRNAs were represented in more than 70% of the sequence reads in one tumor nodule (Fig. 1E), (ii) whether the barcode of a particular shRNA appeared in multiple tumors, (iii) whether more than one shRNA targeted the same gene, and (iv) whether the genes showed copy number variations or mutations in human tumors (Fig. S2A). A secondary reconfirmation screen with selected 16 genes was then performed. The shRNAs representing each of the selected 16 genes were cloned into the CA2-Cre vector, and pooled lentiviruses of the 16 shRNAs were intratracheally instilled into LSL-KRas mice, followed by IVIS imaging. Large tumor nodules were collected at 125 d postinfection, and shRNAs were determined by sequencing the amplicons of the genome-integrated shRNAs (Fig. S2B). The genes that were highly represented were determined as validated by the secondary screen for the tumor suppressor activity (Fig. 1F).

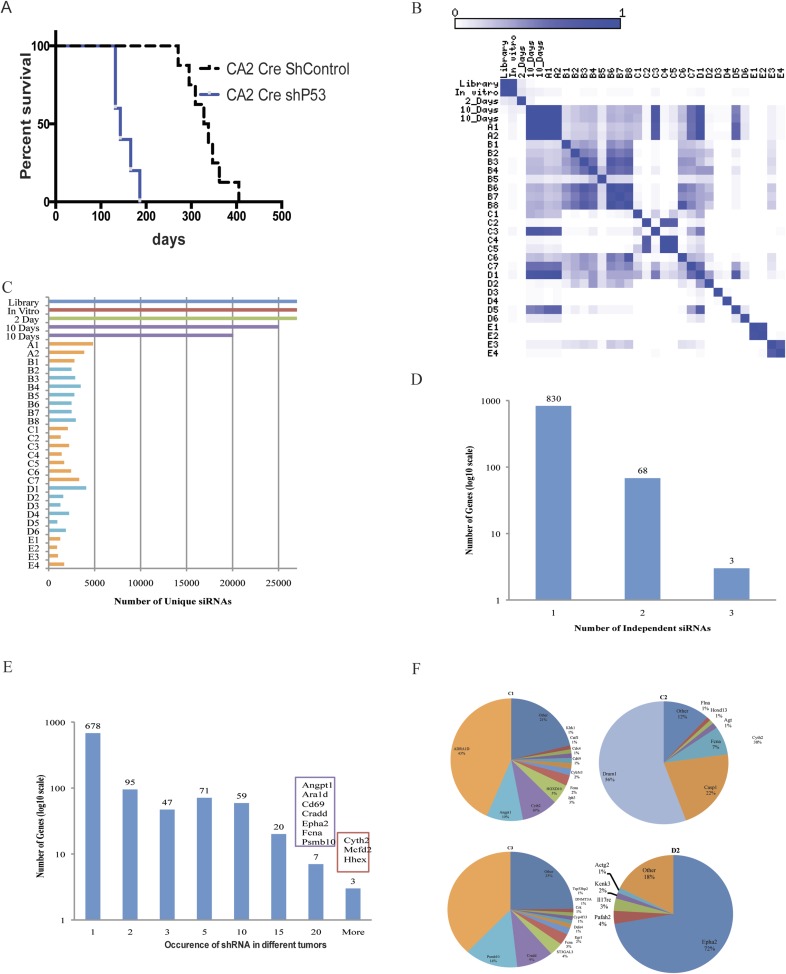

Fig. S1.

An in vivo high-throughput screen to identify tumor suppressors in the context of KRasG12D activation. (A) Survival curve of LSL-KRas mice intratracheally injected with lentiviruses CA2-Cre-shControl (n = 8) or CA2-Cre-shP53 (n = 6). (B) Pearson correlation showing overall distribution of the normalized shRNA read counts from the shRNA plasmid library, transduced 293T cells, and infected lungs on second-day and 10-d and endpoint tumors. (C) Number of unique shRNAs in the deconvoluted barcodes in plasmid, cells in vitro, infected early mouse lungs, and endpoint tumors as in B. (D) Number of genes with one, two, or three significantly enriched (mean + 2 SD > 0.2% of total sequence reads) shRNAs targeting that gene. For genes with two or more enriched shRNAs, genes are categorized by how many shRNAs targeted that gene. (E) The shRNA barcodes identified after sequencing were represented as the number of times each shRNA was represented in independent tumors. (F) Pie charts of the most abundant shRNAs in representative endpoint tumors. The area for each shRNA corresponds to the percentage of total reads from the tumor for the shRNA.

Fig. 1.

An in vivo high-throughput screen identified tumor suppressors in the context of KRasG12D activation. (A) Diagram of the lentiviral vector that was used to generate the library. (B) Schematic of the screen performed in the study. (C) Lentiviral shRNA library in LV-CA2-Cre vector were intratracheally delivered into LSL-KRas mice and imaged after 150 d before collection of tumors. (D) Paraffin sections of the tumor are stained with hematoxylin and eosin and immunostained with surfactant protein C (SFTPC) or CC10 antibodies. (E) The genomic DNA isolated from tumors was sequenced to identify barcodes, and barcodes representing the most in each of the tumors are shown. (F) A subpool of 16 individually cloned shRNAs in the LV-CA2-Cre vector was generated to reconfirm the tumor suppressor potential of the selected genes. The list shows only reconfirmed genes after secondary confirmation in mice. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

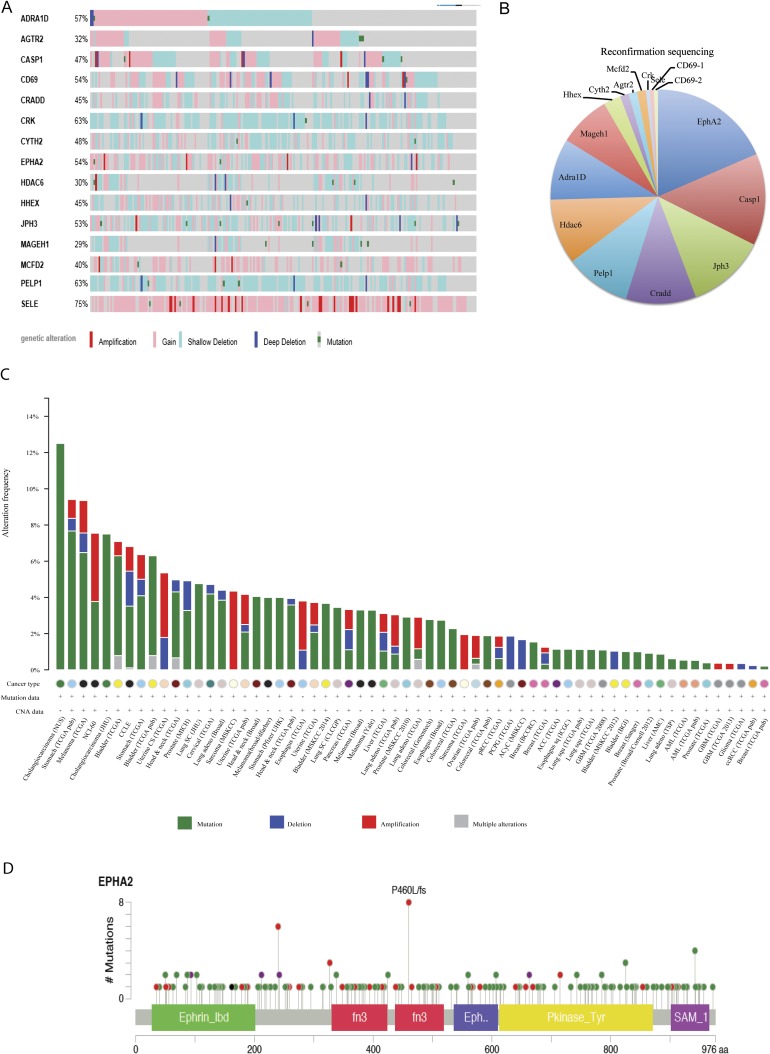

Fig. S2.

The cancer genome analysis of EphA2 alterations. (A) The Cancer Genome Atlas analysis of 16 genes that were used for reconfirmation secondary screen in lung adenocarcinoma patients. (B) The secondary screen with small subpool of 16 candidate shRNAs was done. Cloning and sequencing of PCR-amplified genome-integrated shRNAs was performed, and the pie chart represents sequences detected, plotted as the percentage of total sequences. (C) Cbioportal analysis of EphA2 across all cancers. Green, mutations; blue, deletions; red, amplifications. (D) Cbioportal analysis of mutations of EphA2 across all cancers.

Knockdown of Ephrin Receptor A2 Cooperates with KRasG12D to Generate Lung Adenocarcinoma in Mice.

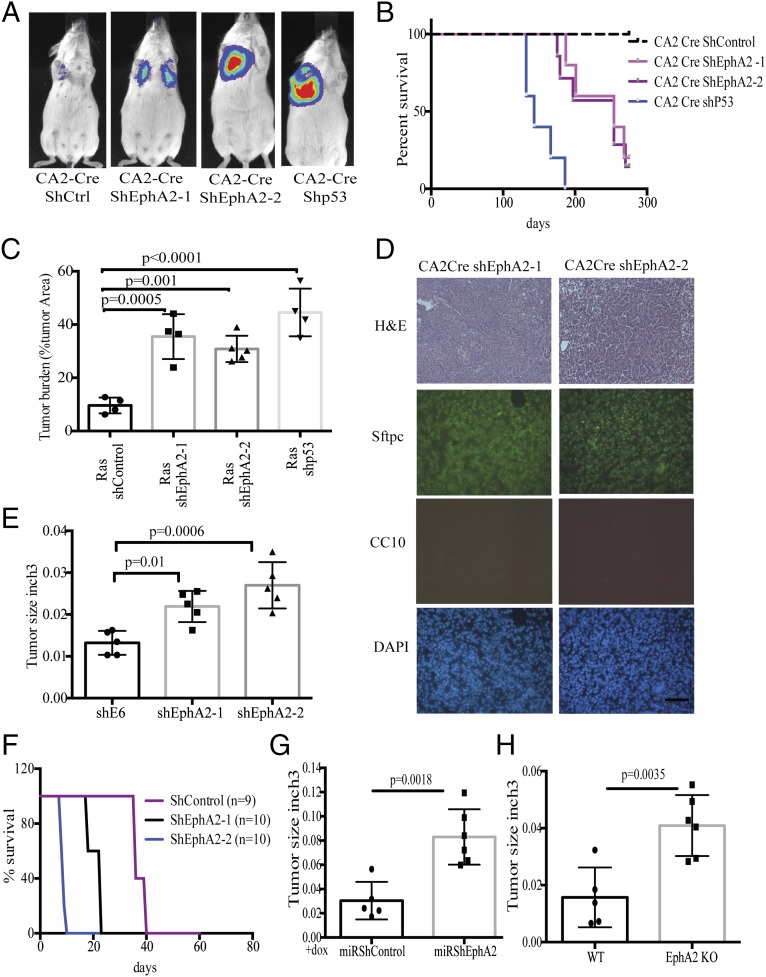

Ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2) was chosen for further functional characterization of its tumor suppressor activity. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data indicated that EphA2 is frequently altered across all human cancers (Fig. S2C). The majority of these alterations include frameshift or truncating mutations indicating loss of function (Fig. S2D). In lung adenocarcinoma patients, shallow or single allele deletions of Epha2 were observed in a large number of patients (23%, 54 of 230 patients), again emphasizing its possible tumor suppressor function (Fig. S2A). Altogether, these observations suggest a potential tumor suppressor function for EphA2. In addition, the barcode representing EphA2 is enriched in sequences from multiple tumors (Fig. S1E), and two independent shRNAs were detected in the sequencing. To test the hypothesis that loss of EphA2 contributes to KRasG12D-induced tumorigenesis, we generated two different shRNAs targeting EphA2—one that is represented highly in the tumors, and an additional independent shRNA. Knockdown of EphA2 was confirmed both at the RNA and protein level (Fig. S3 A and B). Lentiviruses expressing both the EphA2 shRNAs and a nontargeting control shRNA in the CA2-Cre vector were intratracheally delivered into LSL-KRas mice. Luciferase imaging analysis showed the development of tumors by 4–6 mo in EphA2 knockdown mice compared with control knockdown mice (8–10 mo) (Fig. 2A). Survival of the mice transduced with shEphA2 was intermediate between shControl and shP53 mice (Fig. 2B). EphA2 knockdown mice showed high tumor burden compared with control knockdown mice (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3C). Histological features (H&E), positive immunostaining for Sftpc, and negative staining for CC10 demonstrated that these tumors are adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2D). Analyses of EphA2 expression in the tumor showed that KRasG12D alone (shControl) tumors have increased EphA2 levels compared with normal lung whereas shEphA2 tumors had reduced EphA2 (Fig. S3 D and E). Further, these tumors also exhibited a typical oncogenic KRas signature similar to the studies as described previously (29). Together, these observations indicated that knockdown of EphA2 cooperated with KRasG12D in promoting tumorigenesis in lung adenocarcinoma. The paradoxical increase in EphA2 in the context of KRasG12D alone suggests that EphA2 functions as negative regulators (30) of KRasG12D-mediated tumorigenesis.

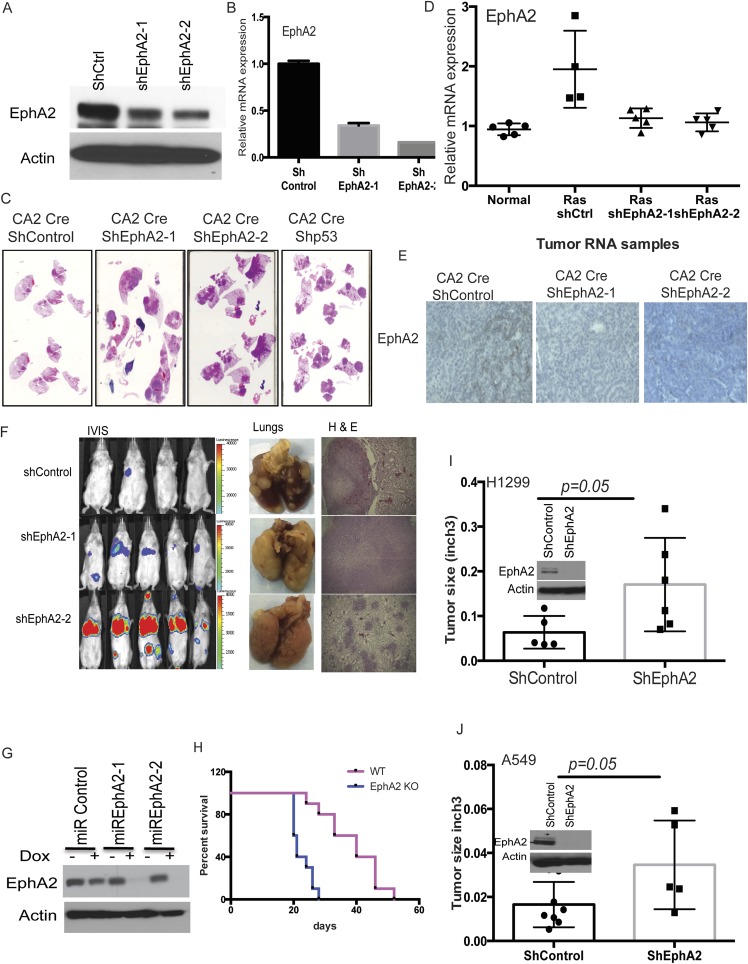

Fig. S3.

Loss of EphA2 promotes tumorigenesis in mice in the context of KRasG12D. (A) M3L2 cells that were stably transduced with lentiviruses expressing shControl, shEphA2-1, or shEphA2-2 were analyzed for expression of EphA2 mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR and (B) EPHA2 protein by Western blotting. (C) H&E-stained paraffin sections of shControl, shEphA2-1, shEphA2-2, and shP53 tumors showing tumor burden. (D) Expression of EphA2 mRNA and (E) EPHA2 protein in tumors from shControl, shEphA2-1, and shEphA2-2 mice compared with normal lung. (F) Luciferase imaging, lungs, and H&E staining of tumor sections from mice i.v. injected with shControl, shEphA2-1, or shEphA2-2 stable M3L2 cells. (G) M3L2 cells that were stable cells with miR30-based dox-inducible shEphA2-1, shEphA2-2, or shControl were treated with doxycycline (1 μg/mL), and lysates were prepared after 72 h. The lysates were immunoblotted for EPHA2. (H) Survival curve of FVB mice i.v. administered with WT or EphA2 knockout cell lines (n = 5 for each group). (I) H1299 cells or (J) A549 cells were transduced with Lenti-shControl or Lenti-shEphA2, the stable cells were s.c. transplanted into NSG mice, and tumor size was assessed after 8 wk for H1299 and 12 wk for A549 (n = 5 for each group).

Fig. 2.

Loss of EphA2 promotes tumorigenesis in mice in the context of KRasG12D. (A) Luciferase imaging of LSL-KRas mice at 150 d after intratracheal transduction with lentiviruses expressing Cre and shControl, shEphA2-1, shEphA2-2, and shP53. (B) The Kaplan–Myer survival curve of mice after intratracheal transduction with lentiviruses expressing Cre and shControl (n = 10), shEphA2-1 (n = 8), shEphA2-2 (n = 10), and shP53 (n = 5). (C) Tumor burden in different groups was calculated using H&E-stained whole sections and expressed as the ratio of tumor area to total area. (D) The tumor sections were stained with H&E, SFTPC, CC10, and DAPI to show features of adenocarcinoma. (E) Stable cell lines expressing shControl, shEphA2-1, and shEphA2-2 were generated and s.c. injected into NSG mice, and tumor size was calculated after 8 wk at the time of collection (n = 5 for each group). (F) Survival curve of FVB mice i.v. administered with shControl or shEphA2 stable cell lines (n = 5 for each group). (G) Stable cell lines with dox-inducible shEphA2 in miR30-based construct were generated and treated with dox before s.c. injection in NSG mice, and tumor size was calculated after 8 wk at the time of collection. Mice were given dox chow for the entire period until collection (n = 5 for miRshControl and n = 6 for miRshEphA2). (H) CRISPR/Cas9-generated EphA2 knockout cells and isogenic WT control cells that were s.c. injected in NSG mice (n = 5 for WT and n = 6 for KO). Tumor volumes were measured after 8 wk postinjection. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Knockdown of EphA2 Promotes Tumorigenesis in Tumor Cell Xenografts in Mice.

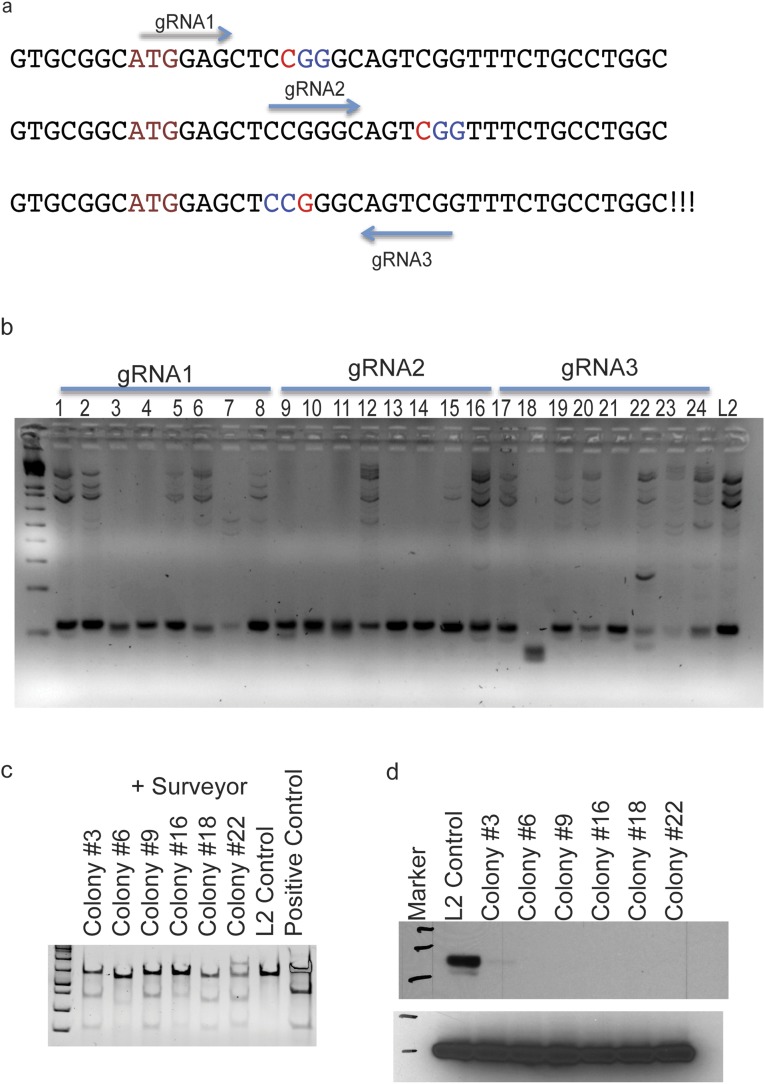

To further test the effect of the silencing of EphA2, we generated shEphA2 or shControl stable cell lines in a mouse lung adenocarcinoma cell line that was derived previously (18) (Fig. S3 A and B). Subcutaneous xenografts or i.v. lung colonization experiments indicated that knocking down EphA2 enhances tumor development in immunocompromised mice or immunocompetent syngeneic mice (NSG and FVB mice) (Methods) (Fig. 2 E and F and Fig. S3F). Next, we generated doxycycline-inducible shRNA stable lines, which, upon doxycycline treatment, showed down-regulation of EphA2 expression (Fig. S3G). s.c. xenograft of dox induced control shRNA or EphA2 shRNA lines showed enhanced tumor development in immunocompromised mice (Fig. 2G). To further confirm that loss of EphA2 promotes tumor development, we generated a CRISPR/cas9-mediated knockout cell line (Fig. S4). Subcutaneous xenograft (Fig. 2H) or i.v. transplantation (Fig. S3H) of EphA2 KO cells promoted tumor development compared with their isogenic WT cells. Further, we knocked down EphA2 in human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, H1299 and A549, both of which harbor mutant Ras and are WT for EphA2 (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia). Subcutaneous xenografts of these stable cell lines in immunodeficient mice resulted in enhanced tumor development (Fig. S3 I and J). Together, these experiments indicated that tumor cell-specific knockdown or knockout of EphA2 promotes tumor development in vivo in mice.

Fig. S4.

Generation of EphA2 knockout M3L2 cells. (A) Guide RNAs designed to target EphA2 locus. (B) M3L2 cells were transiently transfected with pX458 vector with guide RNAs and individual GFP positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry to generate individual clones. Genomic DNA from each clone was PCR amplified with primers surrounding the guide RNA target site. WT cells give an ∼110-bp amplicon, and knockout cells with indels give a variable amplicon size. (C) Six colonies that were positive in the PCR-based assay were further analyzed by Surveyor assay and compared with WT control cells. (D) Western blotting of EPHA2 in knockout cells compared with isogenic WT cells (colonies 3 and 6 were from guide RNA1; 9 and 16 from guide RNA2; and 18 and 22 from guide RNA3).

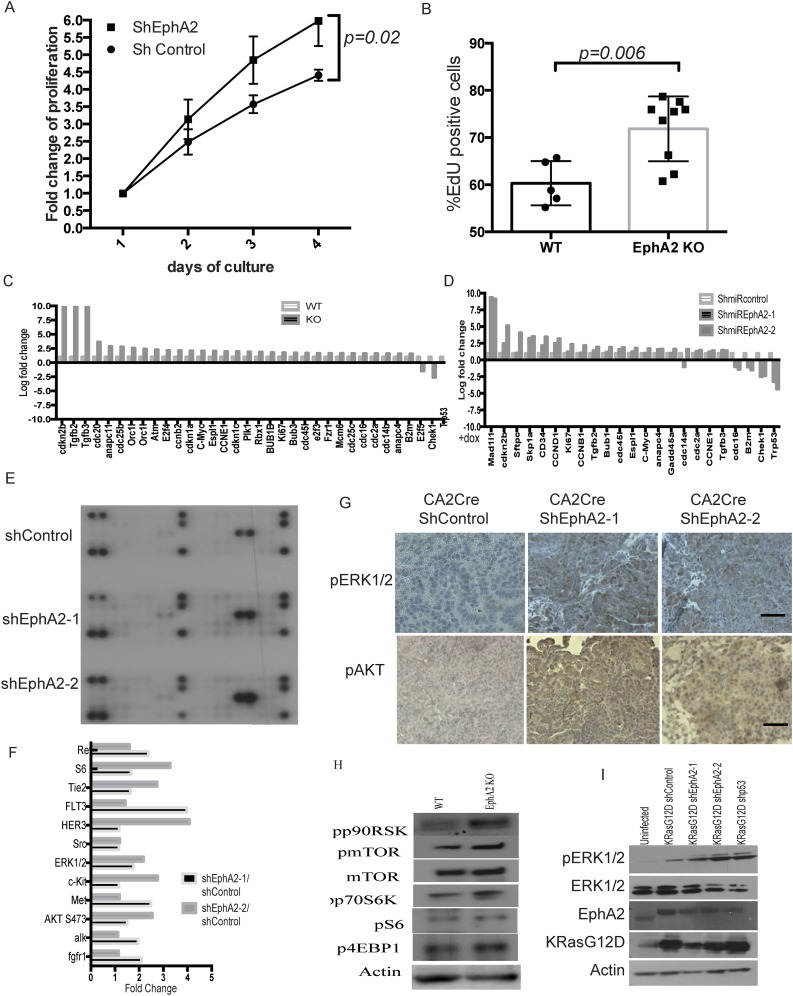

Loss of EphA2 Activates Cell Proliferation in Vivo and in Vitro.

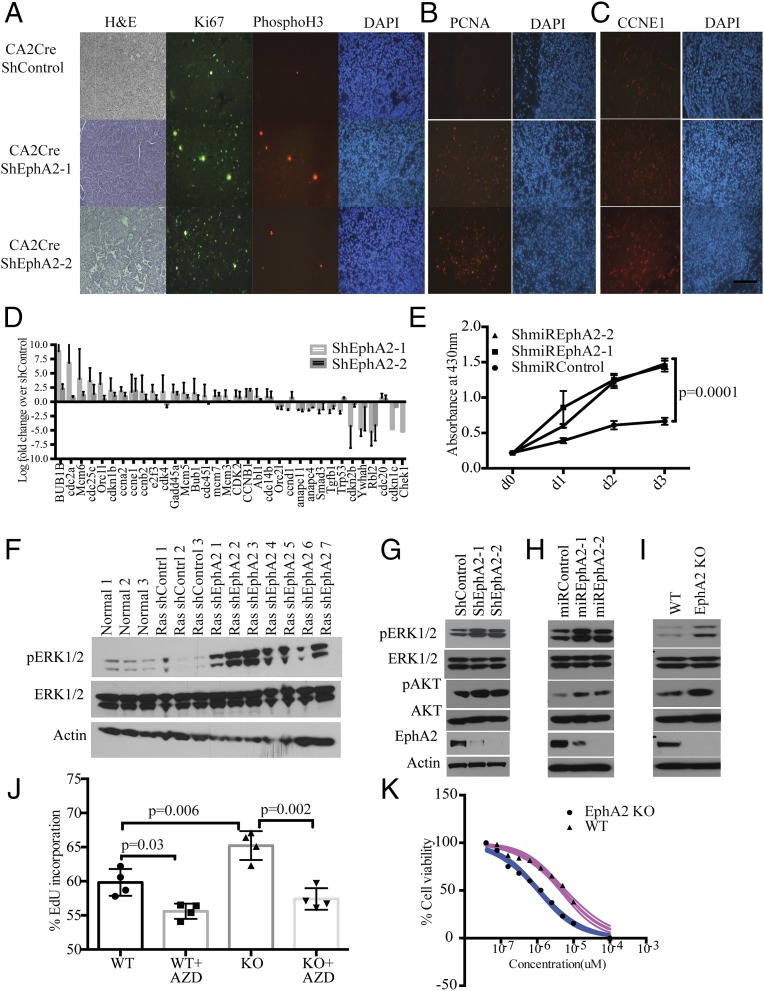

Ephrin receptor A2 has been shown to be involved in various cellular processes, including cell proliferation. To analyze proliferation in the background of loss of EphA2, tumor tissue sections were immunostained with cell proliferation and cell cycle markers Ki67, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), CyclinE1 (CCNE1), and the mitotic marker Phospho H3 (Fig. 3 A–C). Enhanced positive staining of these markers was observed in shEphA2 tumors compared with shControl tumors, suggesting augmented proliferation. In EphA2 silenced tumors, 10–20% of cells were positive for Ki67 (quantitation of Ki67-positive cells to total number of cells), comparable with p53 knockdown tumors (18), implying active cycling of cells and increased cell proliferation. Further, gene expression analysis by quantitative RT-PCR array for cell cycle regulating genes (Fig. 3D) indicated an increase in cell proliferation-associated genes, such as cyclins and Mcm genes, and decreased expression of cell cycle/cell proliferation inhibiting genes (Tp53, Chek1). Next, we analyzed proliferation in vitro in stable cell lines that were generated previously. Cell proliferation assays (WST1 assay and EdU incorporation assay) indicated that constitutive EphA2 knockdown cells (Fig. S5A) or inducible EphA2 knockdown cells (Fig. 3E) proliferate faster than control knockdown cells. Similarly, EphA2 knockout cells exhibited increased proliferative capacity (Fig. S5B). In addition, a quantitative RT-PCR array for cell cycle-regulating genes revealed changes in the cell proliferation signature in EphA2 knockdown cells or knockout cells similar to tumor tissues (Fig. S5 C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that EphA2 loss enhances cell proliferation and thereby tumorigenesis.

Fig. 3.

Loss of EphA2 augments cell proliferation through enhanced ERK1/2 pathway activation. (A) The tumor sections from KRasG12D-shControl or KRasG12D-shEphA2 lentivirally transduced mice were stained with H&E, Ki67, Phospho H3, (B) PCNA, and (C) CCNE1 by immunofluorescence. (D) qPCR array of cell cycle/proliferation genes was done with RNA isolated from tumors, and the genes significantly changed are represented over shControl tumor levels. (E) Cell survival assay with M3L2 cells that are stably transduced with dox-inducible shControl and shEphA2-1 and shEphA2-2. Cells with dox-inducible shEphA2 show enhanced growth compared with cells with dox-inducible shControl. The experiment is the average of three biological replicates. (F) The tumor lysates prepared using individual tumor nodules from shControl or shEphA2 were immunoblotted for phospho ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 and actin. (G) Cell lysates from shControl or shEphA2 transduced cells, or (H) dox-induced miRshEphA2 or miRshControl cells and (I) M3L2 WT and isogenic EphA2 knockout cells were prepared and immunoblotted for Phospho ERK1/2, ERK1/2, Phospho AKT, AKT, and EPHA2. (J) WT and EphA2 knockout isogenic cell lines were treated with MEK inhibitor, AZD 6244 at 500 nM concentration for 24 h, and cell proliferation was measured by EdU incorporation assay. The data are average of three biological replicates. (K) IC50 of the EphA2 knockout and WT cells was determined, and the cells were treated with AZD6244 for different concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.3125, 0.15625, and 0 μM) and assayed for cell survival using WST-1. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Fig. S5.

Loss of EphA2 augments cell proliferation through enhanced ERK1/2 pathway activation. (A) M3L2 shControl or shEphA2 stable cells were analyzed for cell proliferation by cell viability assay. (B) EphA2 knockout (no. 16) or WT cells were analyzed for cell proliferation by EdU incorporation assay. (C) Quantitative PCR array for cell cycle genes in EphA2KO cells compared with WT cells or (D) dox-inducible EphA2 knockdown cells compared with shControl cells. (E) Tumor lysates from shControl, shEphA2-1, and shEphA2-2 mice were analyzed by phosphoprotein array. (F) Quantitation of phosphoprotein array picture using ImageJ. (G) Phospho ERK1/2 and phospho AKT staining in paraffin tumor sections from shControl, shEphA2-1, and shEphA2-2 tumors. (H) WT or EphA2 KO cell lysates were immunoblotted for phospho p90RSK, phospho mTOR, mTOR, phospho p70S6K, phospho S6, phospho 4EBP1, and ACTIN. (I) U2OS cells transiently transfected with KRasG12D-shControl, KRasG12D-shEphA2, or KRasG12D-shP53 constructs and cell lysates collected after 48 h were analyzed for expression of EPHA2, Phospho ERK1/2, ERK1/2, and actin by Western blotting.

Loss of EphA2 Activates ERK1/2 in the Context of KRasG12D.

Taking into account that EphA2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and to delineate signaling mechanisms downstream of loss of Ep-induced cell proliferation, we first tested the status of activation of several RTKs and RTK-dependent kinases. We performed a phosphoprotein profiling on EphA2 knockdown tumor lysates and compared with control tumor lysates. Quantification of the data indicates that loss of EphA2 significantly increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2, c-KIT, and AKT and SRC kinases, suggesting activation of multiple signaling pathways (Fig. S5 E and F). It has been known that activation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase is a crucial downstream event following KRas-activating mutations in lung adenocarcinoma (18, 31). So we first tested whether increased phosphorylation of ERK can be observed in vivo in EphA2 knockdown tumors compared with control tumors. As shown in Fig. S5G, increased ERK phosphorylation was observed in the tumor sections of EphA2 knockdown tumors as opposed to control shRNA tumor sections. Increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation was observed in tumor lysates prepared from tumor nodules of EphA2 knockdown tumors compared with control tumors (Fig. 3F). Similarly, increased AKT phosphorylation was also observed in EphA2 knockout tumors (Fig. S5G). Interestingly, shControl tumors showed down-regulated ERK1/2 and AKT phosphorylation, indicating negative feedback mechanisms downstream of KRasG12D activation. These results were further confirmed in EphA2-deficient cells. In constitutive shEphA2 stable cells or inducible shEphA2 cells and in EphA2 knockout cells, increased levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation were observed compared with respective control cells (Fig. 3 G–I). Further, downstream signaling molecules of ERK1/2 and AKT pathways, including p90RSK, mTOR, S6K, and 4EBP1, were also activated (Fig. S5H). Together, these results indicated that loss of EphA2 augments ERK1/2 and AKT activation in the background of mutant KRas. Because loss of EphA2 can augment ERK1/2 activation in the context of mutant KRAS, it is likely that EphA2 limits tumor growth by posing a negative feedback on the RAS-ERK pathway (30). Further, in U2OS cells, where KRas and EphA2 are WT, expression of KRASG12D resulted in enhanced ERK phosphorylation, which is augmented by loss of EphA2 (Fig. S5I). Moreover, EphA2 expression was increased in U2OS cells where only KRASG12D was overexpressed (Fig. S5I). These observations further corroborate previously reported observations (30) that oncogenic RAS signaling is kept in check by feedback inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by EPHA2. Given the increase of ERK1/2 activation due to loss of EphA2, we next assessed the effect of ERK1/2 inhibition by MEK inhibitors AZD6244 and PD0325901 and assessed the survival of cells. MEK inhibition significantly affected cell proliferation as assessed by EdU incorporation (Fig. 3 J and K) in both WT and knockout cells. However, knockout cells exhibited lower IC50 [IC50 1.07 μM ± 0.17 (SD) for AZD6244 and 67 nM ± 12 (SD) for PD0325901] compared with isogenic WT cells [IC50 5.15 M ± 0.95 (SD) for AZD6244 and 231 nM ± 52 (SD) for PD0325901] (Fig. 3K), indicating enhanced constitutive activation of ERK probably leading to increased sensitivity to ERK inhibition. Overall, these results suggest that loss of EPHA2 enhances ERK activation, which is critical for cell proliferation.

EphA2 Loss Activates the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway.

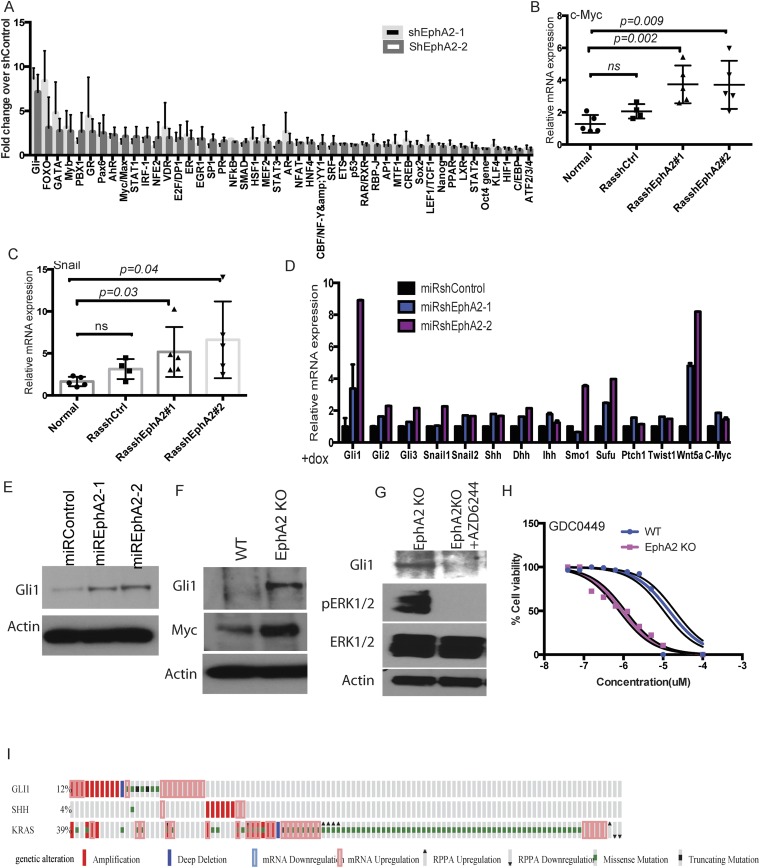

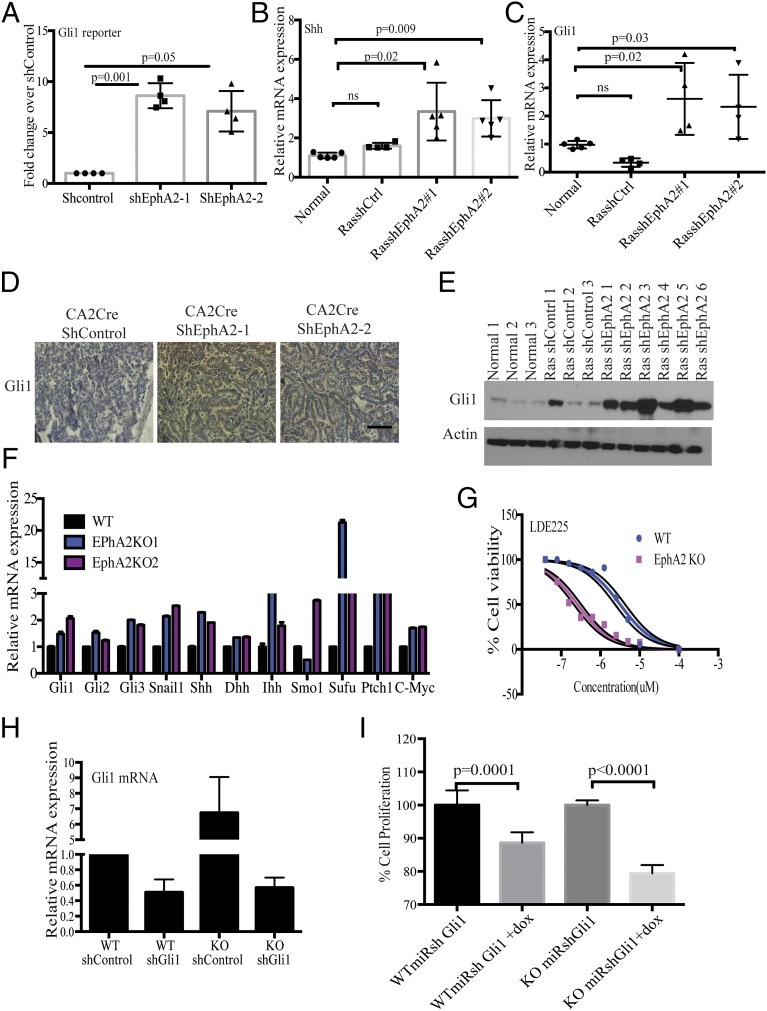

To further decipher the downstream signaling cascades following EphA2 loss, we next performed transcription factor profiling using 48 different transcription factor reporter assays. Multiple transcription factors, including GLI, GATA, MYC, and STAT1/3, were enhanced in shEphA2 cells compared with shControl cells (Fig. S6A). GATA (32) and MYC (33) transcription have been shown to be activated downstream of mutant KRAS, and probably loss of EPHA2 further enhances these transcription factors. Interestingly, GLI transcription factor reporter was increased significantly in EphA2 silenced cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6A). GLI transcription factors are important downstream transcription factors of Hedgehog signaling, which plays key roles in embryonic development and maintenance of adult tissues (34) and is known to be altered in multiple cancers (35). To investigate whether Hedgehog signaling activated in lung adenocarcinoma, we first analyzed mRNA expression of genes involved in Hedgehog signaling in tumors in vivo. Loss of EphA2 significantly augmented mRNA expression of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), a ligand for Hedgehog signaling, and the Gli1 transcription factor and its transcriptional targets (34) c-Myc and Snail (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S6 B and C). Immunohistochemical staining of tumor sections (Fig. 4D) and immunoblotting of tumor lysates (Fig. 4E) revealed increased expression of the GLI1 protein level in shEphA2 tumors compared with shControl tumors. Further, we have previously shown an increase in several cell proliferation genes, such as cyclins, that are also targets for Hedgehog signaling. The increase in Hedgehog signaling genes was more pronounced in vitro in EphA2-deficient cells. EphA2 silenced or EphA2 knockout cells showed a significant increase in mRNA expression of Shh, desert Hedgehog (Dhh), Gli1, and several targets including Snail, c-Myc, Ptch1 (Fig. 4F and Fig. S6D), and GLI1 protein levels (Fig. S6 E and F). Because we observed increased ERK1/2 signaling upon loss of EphA2, we tested whether increased GLI1 expression is dependent on ERK1/2 activation. Inhibition of MEK1/2 by AZD6244 in EphA2 knockout cells significantly decreased GLI1 expression, suggesting that ERK1/2 activation is required for GLI1 expression (Fig. S6G). Because Hedgehog signaling is known to be involved in various cellular processes, including proliferation and tumorigenesis, we tested the effect of modulation of Hedgehog signaling on cell proliferation. Interaction of Hedgehog ligands with negative regulator Patched1 (34) releases suppression and activates Smoothened, finally leading to GLI activation. Inhibition of Smoothened by small molecule inhibitors, such as LDE225 (Sonidegib), and GDC0449 (vismodegib), inhibits the Hedgehog pathway (35). Experiments with LDE225 and GDC0449 showed that EphA2 knockout cells were more sensitive to Hedgehog pathway inhibition compared with isogenic WT control cells (Fig. 4G and Fig. S6H). EphA2 KO cells show lower IC50 of 0.9 ± 0.2 μM (SD) for GDC0449 and 162 ± 42 nM (SD) for LDE225 than isogenic WT cells with IC50 of 15 ± 4.7 μM (SD) for GDC0449 and 3.2 ± 0.9 μM (SD) for LDE225. Further, we generated Gli1-inducible shRNA that down-regulated Gli1 expression (Fig. 4H). Down-regulation of Gli1 reduced cell proliferation in both WT and EphA2 KO cells, but the effect was more distinct in knockout cells (Fig. 4I). These results indicate that, like ERK1/2, Hedgehog signaling is activated upon loss of EphA2 and is important for cell survival and proliferation.

Fig. S6.

Loss of EphA2 increases Hedgehog signaling and is required for cell proliferation. (A) Reporters of 48 different transcription factors were cotransfected with shControl or ShEphA2-1 or shEphA2-2 in LAB6 cells, and luciferase activity was measured after 72 h. The fold change over shControl is represented. The data are a representation of three biological replicates. (B) mRNA expression of c-Myc and (C) Snail in tumor RNAs from shControl or shEphA2-1 or shEphA2-2 mice. (D) mRNA expression of Hedgehog signaling components and targets in dox-inducible EphA2 knockdown cells. (E) GLI1 protein expression in EphA2 inducible knockdown cells or (F) EphA2 knockout cells compared with WT cells. (G) GLI1 protein levels after treatment of knockout cells with AZD6244 (500 nM). (H) EphA2 KO and WT cells were treated with LDE225 at different concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.3125, 0.15625, and 0 μM), and cell survival was performed using WST1. The data were statistically analyzed to determine IC50. (I) cBioportal analysis of KRas, Gli1, and Shh in lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Fig. 4.

Loss of EphA2 increases Hedgehog signaling and is required for cell proliferation. (A) GLI reporter assay in cells transiently cotransfected with GLI reporter and shControl or shEphA2-1 or shEphA2-2. Quantitative RT-PCR for expression of (B) Shh and (C) Gli1 in RNA isolated from ShControl, ShEphA2-1, and shEphA2-2 tumors and compared with normal lung. (D) GLI1 immunostaining in paraffin sections of ShControl or ShEphA2 tumors. (E) Western blotting of GLI1 in lysates of shControl and shEphA2 tumor nodules. (F) mRNA expression of Hedgehog signaling components and targets in EphA2 knockout cells compared with respective controls. (G) WT and EphA2 KO cells were treated with GDC0449 for different concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.3125, 0.15625, and 0 μM) and assayed for cell survival by WST-1. (H) WT and EphA2 KO cells were transfected with shControl or shGli1, and the mRNA levels of Gli1 were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. (I) Cell proliferation by WST1 was assessed in cells that were stably expressing dox-inducible Gli1shRNA expression in WT and EphA2 KO cells. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Ligand-Activated EPHA2 Reduces Cell Proliferation and ERK Activation.

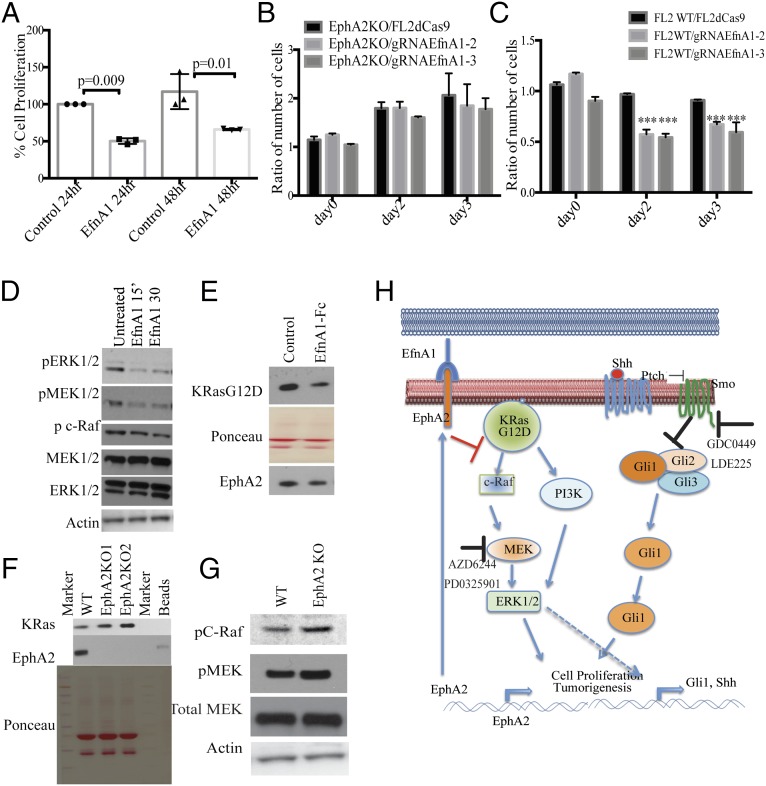

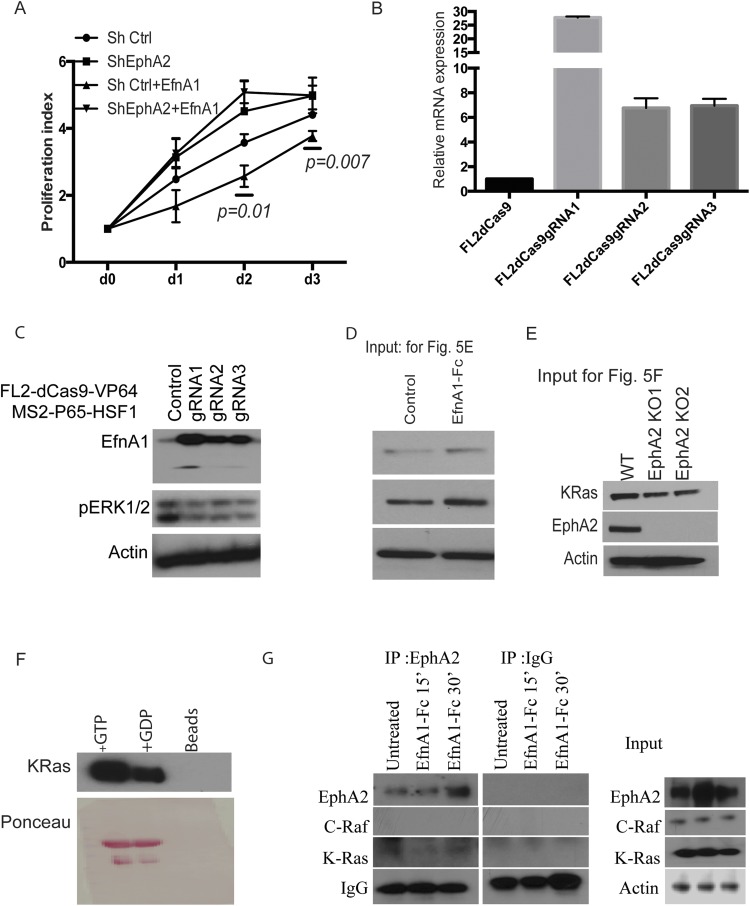

EPHA2 is a receptor kinase that interacts with Ephrin ligands to activate downstream signaling cascades and inhibits growth-promoting signaling (23, 26). We therefore assessed whether activation of EPHA2 can inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell proliferation. Treatment of cells with Fc-conjugated EFNA1 leads to decreased cell proliferation in M3L2 cells or shControl cells but not shEphA2 cells, as assessed by a cell survival assay (Fig. 5A and Fig. S7A). Further, by using the CRISPR/dCas9 system, we generated EFNA1 overexpression from its endogenous locus. We generated three different guide RNAs that achieved varying levels of ligand expression, as shown by mRNA and protein levels (Fig. S7 B and C). Coculture experiments of these individual guide RNA-expressing cells with either EphA2 WT or knockout cells were carried out, and cell numbers were assessed by flow cytometry. Knockout cells (Fig. 5B) showed increased cell numbers and had no effect of ligand on cell growth, but WT cells (Fig. 5C) were inhibited for their proliferation and showed decreased cell numbers. These results suggested that activation of EPHA2 by its ligand promotes its tumor suppressor function and results in decreased cell viability and cell proliferation. Because we have shown that loss of EphA2 can stimulate ERK phosphorylation, we analyzed whether binding of EFNA1 with the EPHA2 receptor can affect ERK1/2 activation. Immunoblotting analyses demonstrated that EFNA1–EPHA2 interaction results in decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5D). To further assess the mechanism of ligand-induced inhibition of the ERK1/2 pathway, we evaluated the activation status of ERK upstream kinases MEK1/2 and c-RAF and binding of c-RAF to KRAS. Both MEK1/2 and c-RAF decreased upon EFNA1-Fc treatment (Fig. 5D). Immunoprecipitation with GST-tagged RAS binding domain (RBD) of RAF indicated that RAS-RAF binding was reduced upon EFNA1-induced EPHA2 activation (Fig. 5E and Fig. S7D). Immunoblotting of these GST-RBD–immunoprecipitated lysates for EPHA2 revealed that EPHA2 was pulled down along with RAS, suggesting a plausible interaction of EPHA2 with RAS-RAF. Further, immunoprecipitation with the EPHA2 antibody pulled down detectable KRAS, albeit at low levels that are not altered by treatment with EfnA1-Fc treatment (Fig. S7G). However, the role of this interaction remains elusive. Additionally, immunoprecipitation of KRAS in knockout cells showed an increased level of RAS–RAF interaction (Fig. 5F and Fig. S7E) that resulted in increased RAF and MEK phosphorylation (Fig. 5G). Overall, our results demonstrate that ligand-activated EPHA2 functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting ERK1/2 pathway and proliferation, suggesting that activation of EPHA2 can be an important therapeutic target.

Fig. 5.

Ligand-mediated activation of EPHA2 inhibits cell proliferation. (A) M3L2 cells were treated with EFNA1-Fc (1μg/mL) for 24 or 48 h, and cell survival was assayed. (B) M3L2-dCas9-VP64-GFP control cells or EfnA1 guide RNA 1 or guide RNA2 transduced cells were cocultured with EphA2 KO cells or WT cells (C), and the cell numbers were assessed by flow cytometry for GFP+ or GFP− populations. The data are expressed as the ratio of cell numbers from da y0 to day 2 or day 3. (D) M3L2 cells were treated with EFNA1-Fc at 1 μg/mL for time points as indicated, and lysates were immunoblotted with pEPHA2, EPHA2, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, pMEK, and pC-RAF. (E) EFNA1-Fc (1 μg/mL) treated M3L2 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GST-Ras binding domain of c-RAF and immunoblotted for KRAS and EPHA2. The PVDF membranes were ponceau stained as a control for loading. (F) EphA2 KO and WT cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GST-RAF1RBD and immunoblotted for KRAS and EPHA2. Ponceau-stained membrane is shown for loading control. (G) Phospho RAF and PhosphoMEK1/2 in EphA2 KO or WT cells. (H) Mechanistic model of EphA2-mediated tumor suppression in the context of KRasG12D activation.

Fig. S7.

Ligand-mediated activation of EPHA2 inhibits cell proliferation. (A) Cell survival assay of ShControl cells or shEphA2 cells that were treated with EFNA1-Fc after time points as indicated. (B) M3L2-dCas9VP64-GFP cells were transduced with EfnA1 guide RNA expressing lentiviruses, and the EfnA1 mRNA or (C) protein levels of EFNA1 were analyzed. Protein levels of phospho ERK1/2 and Actin were also analyzed. (D) Input lysates from Fig. 5E were analyzed for KRAS, EPHA2, and ACTIN. (E) Input lysates from Fig. 5F were analyzed for KRAS, EPHA2, and ACTIN. (F) Western blotting of KRAS in immunoprecipitates from the lysates that were treated with GTP or GDP. (G) EFNA1-Fc (1 μg/mL) treated M3L2 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with EPHA2 antibody, and lysates were immunoblotted for c-RAF, K-RAS, EPHA2, and ACTIN. Input lysates were used as controls.

Discussion

Lentiviral vector-mediated high-throughput screens can be used to rapidly test the role of a large number of copy number alterations or mutations that are found in integrated genome sequencing of cancer by The Cancer Genome Atlas consortium. Here, we describe an shRNA-mediated screen to identify genes with tumor suppressor function and validate a large set of genes in a relatively short timeframe. Screens mediated by shRNA are a useful approach to validate genes that are down-regulated or haploinsufficient tumor suppressors where deletion of one allele leads to loss of tumor suppression. Mining TCGA data revealed a large number of shallow deletions or single allelic deletions but not homozygous deletions, which are remarkably infrequent. Recently, using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome-editing technology, some of the known alterations in the background of KRasG12D have been studied (36). Nevertheless, a knockdown approach is promising to recapitulate and model down-regulation of gene expression and single allelic deletion that results in haploinsufficiency. Our study found several genes with potential tumor suppressor-like properties, including EphA2, Casp1, Cradd, Hdac6, Pelp1, Jph3, Adra1d, and Mageh1. Several of these genes are altered in human lung adenocarcinoma patients, but their role in lung adenocarcinoma remains elusive. In addition to testing for possible tumor suppressors, lentiviral delivery further would be vital to test a diverse array of mutations observed in genes for their role in tumorigenesis. Mining the data from The Cancer Genome Atlas is possible to define the gene lists and may be targeted by lentiviral delivery of shRNAs, guide RNAs, or cDNAs of mutant genes.

In this study, we identified and verified EphA2 as a tumor suppressor that cooperates with KRasG12D in promoting lung adenocarcinoma. Previous studies have described paradoxical observations indicating both tumor suppressive and oncogenic properties of EphA2. In the background of these observations, our studies show that lung tumor-specific knockdown of EphA2 exacerbates adenocarcinoma development similar to knockdown of Tp53. In contrast to EphA2 whole body knockout combined with KRasG12Dla2 transgenic mice studies (37), our experiments caused loss of EphA2 specifically in tumor cells and this deletion promoted tumor development in the context of tumor cell-specific expression of oncogenic KRasG12D. These observations suggest that EphA2 has different tumor cell autonomous and nonautonomous roles in tumor development. These results also corroborate previous studies showing that impaired EphA2 expression in the tumor microenvironment severely affects angiogenesis and tumor development (38). Together, these observations suggest that, whereas tumor-specific deletion of EphA2 promotes tumorigenesis, the contribution of EphA2 from tumor stroma and endothelial cells might be important for tumor development. Some human lung adenocarcinoma patients show increased expression of EphA2, and it is correlated with poor prognosis (39), whereas coexpression of high EphA2 and EfnA1 has favorable survival (40). Interestingly, TCGA data analysis revealed that EphA2 and EfnA1 alterations occur independently, and it is intriguing to hypothesize that tumors with EphA2 and EfnA1 coexpression might be negatively selected in the early stages of tumor development. However, the overexpressed EphA2, in the absence of cognate ligands (23, 24, 30, 41), can function to promote tumorigenesis in a ligand-independent manner. Overexpressed EPHA2 can be phosphorylated at S897 by activated AKT and can function in a ligand-independent manner to promote cell growth, xenograft tumor development, anoikos resistance (42), and migration of tumor cells (43–46). Additionally, overexpressed EPHA2 is cleaved at the membrane by MT1-MMP metalloprotease and switches its function from ligand-dependent tumor suppressor to ligand-independent tumor-promoting factor (47, 48).

Constitutive activation of KRAS alone is not sufficient to develop tumorigenesis in multiple cancers, including lung adenocarcinoma development (49–51). Negative feedback mechanisms inhibit downstream ERK1/2 and PI3K signaling cascades to cause senescence and to prevent transformation (52–54). Concomitant cooperative mutations in tumor suppressor proteins such as Tp53 help release this negative feedback in addition to affecting the genome stability (18, 31). Further, cooperative loss of these feedback mechanisms was shown to promote Ras-induced leukemogenesis (50). EphA2 has been suggested to be one such negative feedback regulator inhibiting KRAS downstream signaling pathways (30, 55). Our results show that loss of EphA2 promotes cell proliferation by activating proliferative signaling and transcription programs. The gene expression of positive modulators of cell cycle and proliferation is increased upon loss of EphA2. Our studies are in agreement with previous reports regarding ligand-dependent inhibition of ERK1/2 by EPHA2 (56). Therefore, loss of EPHA2 possibly releases this repression of proliferative signaling, leading to proliferation, which otherwise, through interaction with EFNA1 ligand, contributes to tumor suppression. Also, among the various ligands tested for their expression in normal mouse lungs, EfnA1 expression seems to be highly expressed (the average cycle threshold values in qPCR (quantitative RT-PCR) across eight different mouse lungs is ∼21 for EfnA1). In light of these observations, increased expression of EphA2 in Ras-shControl tumors supports this negative feedback regulation and delays tumor development in shControl lungs. Reduced ERK activation and dampened positive staining proliferative markers (Ki67, PCNA, PhosphoH3, and CCNE1) in shControl tumor sections further supports this negative feedback regulation. This regulation is particularly important early in the tumor development because ligand-independent mechanisms of EPHA2-mediated tumor promotion, such as cross talk with AKT, might evolve to subdue the tumor suppressor effects (42, 57). Even though the contribution of EfnA1 ligand in tumor suppression in vivo is challenging to capture in the tumor microenvironment, in vitro treatment of cells with EFNA1 ligand or CRISPR/dCas9-mediated transcriptional activation of EfnA1 or EPHA2 agonist doxazosin (26) inhibited both growth-signaling pathways and proliferation. Intriguingly, the inhibition of the EPHA2-mediated ERK pathway occurs at the level of RAS–RAF interaction, as shown by immunoprecipitation studies (Fig. 5). The presence of EPHA2 in RAF-RBD immunoprecipitates and also the presence of KRAS in EPHA2 antibody immunoprecipitates suggest a plausible association of these proteins at the membrane, probably independent of EFNA1 ligand. Activation of EPHA2 by EFNA1 decreases interaction of active RAS with RAF, thereby inhibiting the downstream RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway. How EPHA2 influences RAS-RAF interaction warrants further investigation. Accordingly, in EPHA2-deficient cells, this RAS–RAF interaction is restored, leading to activation of the downstream ERK1/2 proliferative signaling pathway and contributing to enhanced tumorigenesis. Consequently, chemical inhibition of the ERK1/2 pathway enhances the susceptibility of EphA2 knockout cells, which further highlight the importance of ERK1/2 activation. (Figs. 4 and 5H). Further, it is worth noting that loss of EphA2 appears to have a synergistic effect, with loss of Tp53 during the development of lung adenocarcinoma. The M3L2 cell line, derived from primary tumors harboring KRas and Tp53 alterations, showed enhanced cell proliferation and tumor growth in mouse xenografts when EphA2 receptor was deleted (Figs. 2 and 3). However, tumorigenic cooperation between these alterations in genetic or lentiviral-mediated mouse models remains to be investigated.

Transcription factor analysis in EphA2 knockdown cells revealed activation of the Hedgehog-signaling pathway, which plays central roles in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis (58). Oncogenic KRas or Egfr were shown to cooperate with dominant active Gli2 activation in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (59). In human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines, knockdown of Gli1 and Gli2 affects proliferation, migration, and invasion (60). Moreover, TCGA data analysis of lung adenocarcinoma patients showed that GLI1 and KRAS copy number alterations coexist in a subset of patients (Fig. S6I). In agreement with the published observations, EphA2 loss-induced Hedgehog signaling is critical to cell proliferation. We show increased Shh and Gli1 expression and downstream GLI1 targets both in vivo in tumors and in vitro in cell lines. The increased GLI1 expression in EphA2-deleted cells seems to be dependent on ERK pathway activation because the MEK inhibitor decreased the expression of GLI1. Further targeting the Hedgehog pathway in EphA2 knockout cells either by shRNA to Gli1 or with Smoothened antagonists GDC0449 (Vismodegib) or LDE225 (Sonidegib) reveals increased susceptibility of knockout cells compared with isogenic controls. These observations suggest that loss of EphA2 results in Hedgehog pathway activation and probably provide a therapeutic target for oncogenic KRas-dependent lung cancer (Fig. 5H). Testing the therapeutic efficacy of these inhibitors in our mouse models warrants future research.

In summary, we describe a high-throughput shRNA screen to identify tumor suppressor genes, and, as a proof of principle, we demonstrate EphA2 as a tumor suppressor in the context of KRasG12D activation. This method can be used to test the vast majority of copy number alterations and mutations found in the cancer genome studies. Fig. 5H summarizes the mechanistic model for the role of EphA2 in KRasG12D-mediated lung cancer. In addition to releasing the negative feedback inhibition of EphA2, its loss also induces the Hedgehog-signaling pathway to promote cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Based on our findings, activation of EPHA2 by EFNA1 or inhibition of the Hedgehog signaling pathway might serve as therapeutic targets for KRas-dependent lung adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Mice and Cell Lines.

The LSL-KrasG12D mouse was originally generated in the Tyler Jacks laboratory (20). LSL-Rosa26luc and NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. LSL-Rosa26luc was crossed with the LSL-KrasG12D mouse to get KrasG12DRosa26luc for live animal tumor imaging. FVBN/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred at the Salk animal facility. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Salk Institute approved all of the animal protocols before conducting experiments. A549, H1299, and U2OS cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The M3L2 (FVB background, Luciferase-positive) and LAB6 (B6 background, no luciferase) cell line was derived from the tumors generated previously as described (18), and both these cell lines were derived from LSL-KRas mice infected with CA2-Cre-shP53. The cell lines listed are not part of the contaminated cell line database from the iclac.org/databases/cross-contaminations/ website.

Lentiviral shRNA Library Production, Mice Infection, and IVIS Imaging.

Lentiviruses were produced as described previously (61). pLV-CA2-Cre vector was described previously (18). Lentiviruses were prepared using standard protocols as described. The pooled shRNA library was generated in the pLV-CA2-Cre vector with the help of Cellecta Inc. The DECIPHER mouse module 1 with 4,825 signaling pathway targets and 27,500 shRNAs was used to generate a pooled shRNA library. All of the sequences of shRNAs and their corresponding barcodes are presented in Dataset S1. Genomic DNA from tumors was isolated using the Qiagen Genomic DNA isolation kit. Next Generation sequencing of barcodes was performed by using Illumina hiSeq2.0 (Illumina), and barcodes were deconvoluted to reveal shRNA identity. The primer sequences used for PCR amplification of barcodes are listed in Table S1. All of the bioinformatics analysis was performed using similar methods described by Chen et al. (9). Detailed software and analysis related information is available upon request. The 8-wk-old LSL-KRas mice were intratracheally transduced with 5 × 104 lentiviral particles by using the protocol as described previously (17, 18). A subpool of shRNAs was generated by individually cloning selected shRNAs into the pLV-CA2-Cre vector, and the virus was prepared as a single pool. All of the selected shRNA sequences including both shRNAs against EphA2 are listed in Dataset S1. Live animal tumor imaging was carried out at time points as described in Results using the IVIS 100 imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences).

Table S1.

List of all primer used in the study

| Primers used for sequencing barcodes | |

| Gex Forward | 5’-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCAUACGAGA-3’ |

| Gex SeqN Reverse | 5’-ACAGTCCGAAACCCCAAACGCACGAA-3’ |

| ShRNA cloning primers | |

| Control Non targetin shRNA U6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGCGCGATAGCGCTAATAATTTTCTCTTGAAAAATTATTAGCGCTATCGCGCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| CD69-mU6-sh1 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACCATGTTGTTACCTGTAAGAATCTCTTGAATTCTTGCAGGTAGCAACATGGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| CD69-mU6-sh2 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACCATTCAAGTTTCTATTCCTTTCTCTTGAAAAGGGATAGAAACTTGAATGGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Mageh1-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGCTGAAGAGAATCGCAATAATTCTCTTGAAATTGTTGCGATTCTCTTCAGCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Hhex-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACTTTGGATTGTTCGTAGTGTTTCTCTTGAAAACACTGCGAACGATCCAAAGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Cyth2-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAAGAAGAGCTAAGTGAAGTTATTCTCTTGAAATAGCTTCACTTAGCTCTTCTAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| PELP1-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGCATTGGTGAATCTTAGTAATTCTCTTGAAATTACTGAGATTCACCAATGCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Agtr2-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACTTAGAGAAATGGACATCTTTTCTCTTGAAAAAGGTGTCCATTTCTCTAAGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Adra1D-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACAACTATTTCATCGTGAATCTTCTCTTGAAAGGTTCACGATGAAATAGTTGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Cradd-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACACCTTCCTAAGCTTATACAATCTCTTGAATTGTGTAAGCTTAGGAAGGTGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Crk-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACTGGATCAATAGAATCCTGATTCTCTTGAAATCGGGATTCTGTTGATCCAGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Mcfd2-mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACAGGAGGGAAACTTTGAGTTGTCTCTTGAACAATTCAAGGTTTCCCTCCTGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| JPH3 mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGCCTTCTTTACTAGGGTTGTTTCTCTTGAAAACAACCCTGGTAGAGAAGGCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| HDAC6 mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACCAAGTAATACTGGAAGGTTATCTCTTGAATAACCTTCCGGTGTTACTTGGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| CASP1 mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGATTTCTTAACGGATGCAATTTCTCTTGAAAATTGCATCCGTTAAGAAATCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| SEL-E mU6 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAACTACCTTAACTCCAATTTGAATCTCTTGAATTCAGATTGGAGTTAAGGTAGAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| shmepha2-1 | 5'CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGACCCAGCTAAGTACTTAGTATCTCTTGAATGCTAAGTGCTTAGCTGGGTCGGGGATCTGTGGTCTCATACA |

| shmepha2-2 | 5'CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGCACAGGGAAAGGAAGTTGTTTCTCTTGAAAACAACTTCCTTTCCCTGTGC GGGGATCTGTGGTCTCATACA |

| sihepha2 | 5’CTGTCTAGACAAAAAGATAAGTTTCTATTCTGTCAGTCTCTTGAACTGACAGAATAGAAACTTATCAAACAAGGCTTTTCTCCAAGG-3’ |

| Dox inducible shRNA cloning primers | |

| EphA2 mir30E 1 Forward | CGGCTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAACCCAGCTAAGCACTTAGCATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATG |

| EphA2 mir30E 1 Reverse | CTCGAATTCTAGCCCCTTGAAGTCCGAGGCAGTAGGCAGACCCAGCTAAGCACTTAGCATACATCTGTGGCTTCACTA |

| EphA2 mir30E 2 Forward | CGGCTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGACACAGGGAAAGGAAGTTGTTTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAAA |

| EphA2 mir30E 2 Reverse | CTCGAATTCTAGCCCCTTGAAGTCCGAGGCAGTAGGCAGCACAGGGAAAGGAAGTTGTTTACATCTGTGGCTTCACTA |

| Gli1miR30Esh Forward | CGGCTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGACATGGGAACAGAAGGACTTTTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAAA |

| Gli1miR30Esh Reverse | CTCGAATTCTAGCCCCTTGAAGTCCGAGGCAGTAGGCAGCATGGGAACAGAAGGACTTTTACATCTGTGGCTTCACTA |

| QPCR primers | |

| CCND1 Forward | GCGTACCCTGACACCAATCTC |

| CCND1 Reverse | CTCCTCTTCGCACTTCTGCTC |

| CCNE1 Forward | GTGGCTCCGACCTTTCAGTC |

| CCNE1 Reverse | CACAGTCTTGTCAATCTTGGCA |

| CCNB1 Forward | GCGTGTGCCTGTGACAGTTA |

| CCNB1 Reverse | CCTAGCGTTTTTGCTTCCCTT |

| PTCH1 Forward | AAAGAACTGCGGCAAGTTTTTG |

| PTCH1 Reverse | CTTCTCCTATCTTCTGACGGGT |

| PTCH2 Forward | CTTCTCCTATCTTCTGACGGGT |

| PTCH2 Reverse | TCCCAGGAAGAGCACTTTGC |

| GLI1 Forward | CCAAGCCAACTTTATGTCAGGG |

| GLI1 Reverse | AGCCCGCTTCTTTGTTAATTTGA |

| FOXL1 Forward | GAGCAGAGGGTCACACTGAAC |

| FOXL1 Reverse | CTTCCTGCGCCGATAATTGC |

| TWIST1 Forward | GGACAAGCTGAGCAAGATTCA |

| TWIST1 Reverse | CGGAGAAGGCGTAGCTGAG |

| SNAI1 Forward | CACACGCTGCCTTGTGTCT |

| SNAI1 Reverse | GGTCAGCAAAAGCACGGTT |

| SNAI2 Forward | TGGTCAAGAAACATTTCAACGCC |

| SNAI2 Reverse | GGTGAGGATCTCTGGTTTTGGTA |

| SNAI3 Forward | GGTCCCCAACTACGGGAAAC |

| SNAI3 Reverse | CTGTAGGGGGTCACTGGGATT |

| WNT5A Forward | CAACTGGCAGGACTTTCTCAA |

| WNT5A Reverse | CATCTCCGATGCCGGAACT |

| CDH1 Forward | CAGGTCTCCTCATGGCTTTGC |

| CDH1 Reverse | CTTCCGAAAAGAAGGCTGTCC |

| EphA2 Forward | GCACAGGGAAAGGAAGTTGTT |

| EphA2 Reverse | CATGTAGATAGGCATGTCGTCC |

| EfnA1 Forward | CTTCACGCCTTTTATCTTGGGC |

| EfnA1 Reverse | TGGGGATTATGAGTGATTTTGCC |

| Ssh Forward | AAAGCTGACCCCTTTAGCCTA |

| Ssh Reverse | TTCGGAGTTTCTTGTGATCTTCC |

| Ihh Forward | CTCTTGCCTACAAGCAGTTCA |

| Ihh Reverse | CCGTGTTCTCCTCGTCCTT |

| Dhh Forward | CTTGGCACTCTTGGCACTATC |

| Dhh Reverse | GACCCCCTTGTTACCCTCC |

| Ptch1 Forward | AAAGAACTGCGGCAAGTTTTTG |

| Ptch1 Reverse | CTTCTCCTATCTTCTGACGGGT |

| Smo Forward | GAGCGTAGCTTCCGGGACTA |

| Smo Reverse | CTGGGCCGATTCTTGATCTCA |

| GLI1 Forward | CCAAGCCAACTTTATGTCAGGG |

| GLI1 Reverse | AGCCCGCTTCTTTGTTAATTTGA |

| GLI2 Forward | CAACGCCTACTCTCCCAGAC |

| GLI2 Reverse | GAGCCTTGATGTACTGTACCAC |

| GLI3 Forward | CACAGCTCTACGGCGACTG |

| GLI3 Reverse | CTGCATAGTGATTGCGTTTCTTC |

| Snail1 Forward | CACACGCTGCCTTGTGTCT |

| Snail1 Reverse | GGTCAGCAAAAGCACGGTT |

| Sufu Forward | GGGACTGCACGCCATCTAC |

| Sufu Reverse | TTGACGATAGCGGTAACCTGG |

| Cyclophilin Forward | GGCCGATGACGAGCCC |

| Cyclophilin Reverse | TGTCTTTGGAACTTTGTCTGCAAAT |

| GAPDH Forward | TGACCACAGTCCATGCCATC |

| GAPDH Reverse | GACGGACACATTGGGGGTAG |

| P53 Forward | GTCACAGCACATGACGGAGG |

| P53 Reverse | TCTTCCAGATGCTCGGGATAC |

| EphA2 guide RNA primers | |

| EphA2-284 Forward | CACCGAGGGGTGCGGCATGGAGCTC |

| EphA2-293 Forward | CACCGGCATGGAGCTCCGGGCAGT |

| EphA2-307 Forward | CACCGCCAGGCAGAAACCGACTGCC |

| EphA2-284 Reverse | AAACGAGCTCCATGCCGCACCCCTC |

| EphA2-293 Reverse | AAACACTGCCCGGAGCTCCATGCC |

| EphA2-307 Reverse | AAACGGCAGTCGGTTTCTGCCTGGC |

| EphA2 Surveyor Forward | AAGGGCAAAAGGGGAGAGTA |

| EphA2 Surveyor Reverse | AGGGTATGGATCCCCAAGAT |

| EfnA1 guide RNA primers | |

| Efna1gRNA1 Forward | CACCGGGGGCAGCGCGCGTCGGGCG |

| Efna1gRNA1 Reverse | AAACCGCCCGACGCGCGCTGCCCCC |

| Efna1gRNA2 Forward | CACCGGAGGGCGGGGCTGGTGTTGG |

| Efna1gRNA2 Reverse | AAACCCAACACCAGCCCCGCCCTCC |

| Efna1gRNA3 Forward | CACCGGGAGGAAGGGAAAAAGACTC |

| Efna1gRNA3 Reverse | AAACGAGTCTTTTTCCCTTCCTCCC |

| KRas mice Genotyping primers | |

| K004 : | 5'-GTC GAC AAG CTC ATG CGG GTG -3' |

| K006 : | 5'-CCT TTA CAA GCG CAC GCA GAC TGT AGA -3' |

| K005 : | 5'-AGC TAG CCA CCA TGG CTT GAG TAA GTC TGC A -3' |

Cell cycle proliferation qPCR array was obtained from Takara Inc. KRas mice genotyping primers from Jackson Laboratory. The underline indicates the shRNA targeting sequence.

Stable Cell Lines, Knockout Cell Lines, Overexpression Cell Lines, and Mouse Xenografts.

M3L2 cells were derived in our laboratory from lung tumors originated in KrasG12DRosa26luc mice transduced with the CA2-Cre-shP53 lentivirus (18). Various stable cell lines were generated by transducing cells with lentiviruses expressing shControl, shEphA2-1, shEphA2-2, dox-shControl, dox-shEphA2-1, and dox-shEphA2-2. The dox-inducible cells were treated with 1 μg/mL doxycycline to induce expression of shRNA. The CRISPR/cas9 system was used to generate EphA2 knockout cells. Guide RNA targeting EphA2 was cloned using sense sequence CACCggcatggagctccgggcagt and antisense sequence AAACactgcccggagctccatgcc. The oligos were annealed and ligated to BbsI (NEB) digested pX458GFP vector (Addgene). The M3L2 cells were transiently transfected with the vector and sorted for GFP-positive cells. Individual colonies obtained from sorted cells were analyzed for expression of EphA2. Deletion of both alleles of EphA2 was further confirmed by cloning and sequencing the targeted genomic region. Knockdown or knockout cells (106 tumor cells or otherwise specified) were s.c. transplanted into NSG mice or FVB mice. Tumor sizes were measured at the time of collection and processed for histology. Intravenous transplantation was performed by injecting 5 × 105 cells into the tail vein of the FVB mice. Only the mice that were positive for lung-specific luciferase imaging after a week postinjection were further used to generate a survival curve. The CRISPR/mutant cas9 system was used to achieve endogenous transcriptional activation of EfnA1 as reported (62). Briefly, Lenti-dCas9 (D10A, N863A) VP64, Lenti-MS2-P65-HSF1, and Lenti-hU6-sgRNA (MS2) constructs were obtained from Addgene. Guide RNAs targeting the first ∼100-bp region of the first exon of EfnA1 locus (taken from sam.genome-engineering.org/database/) were cloned into the Lenti-hU6-sgRNA (MS2) vector. Triple lentiviral stables in the M3L2 cell line were generated, and qPCR and Western blotting confirmed the expression of EfnA1.

Histology, Immunohistochemical Staining, Immunofluorescence Staining, and Immunoblotting.

Mouse lung samples were inflated using 10% (vol/vol) formalin and fixed overnight. The lung samples were then transferred to 70%(vol/vol) ethanol, paraffin embedded, and sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) and immunohistochemical or immunofluorescence staining. Paraffin sections were immunohistochemically stained using the Elite ABC system (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Immunofluorescent staining and immunoblotting were performed according to standard protocols. Antibodies were purchased from Millipore (SFTPC, CC10, PCNA, and Phospho H3), Cell Signaling (EphA2, Phospho EphA2 Y594, phospho-Erk, total Erk, phospho-Akt, total Akt, phospho-MEK, phospho-cRaf, and Cleaved Caspase 3), and Novus Biologicals (Gli1). The RTK phosphoprotein profiler array was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, and the assay was performed using tumor lysates as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoprecipitation, Active Ras Detection, and Phosphoprotein Profiling.

An active Ras detection kit was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and immunoprecipitation experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein G agarose beads were used to perform EphA2 immunoprecipitation using EphA2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). The pulled down lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti K-Ras antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). The proteome profiler mouse phospho-RTK array kit was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, and the assay was performed using the manufacturer’s instructions using mouse tumor lysates.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

A Qiagen RNeasy kit was used to prepare total RNA isolated from homogenized tumor samples or cell lines. RNA was reverse transcribed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems) with random primers. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate using the SYBR green method, and samples were run on an SDS 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Results were analyzed for the relative expression of mRNAs normalized against GAPDH and cyclophilin. The data are represented and analyzed for statistical significance using Prism 6.0 software. The cell cycle/cell proliferation PCR array was purchased from Takara Inc. All of the other primers are listed in Table S1.

Reporter Assays.

A pathway scan multipathway reporter kit was purchased from GM Biosciences. The kit contains 48 different transcription factor reporters with firefly luciferase combined with Renilla luciferase construct as control. LAB6 cells were cotransfected with the reporter constructs and either of shControl, shEphA2-1, or shEphA2-2. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were lysed in reporter lysis buffer, and both firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were assayed using luminometer (Perkin-Elmer). A dual luciferase kit was used from Promega. The Gli1 reporter was also assayed similarly and was purchased from GM Biosciences.

Chemical Inhibitors, Cell Survival Assay, and EdU Cell Proliferation Assays.

Chemical inhibitors for MEK1 (PD0325901, AZD6244) and Smoothened inhibitors (GDC0449, LDE225) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. The cells were treated with inhibitors, and DMSO was used as solvent control. The cell survival/cell proliferation assay was performed using WST-1 reagent (Roche). An EdU incorporation assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a Click-it EdU incorporation kit (Life Technologies).

Statistics.

All of the statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism software. A Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences of gene expression or tumor size or differences in proliferation assays. The differences between multiple groups was analyzed by ANOVA. The Kaplan–Meier curves were analyzed by Log-rank test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dinorah Friedmann-Morvinski, Gerald Pao, Quan Zhu, and all the I.M.V. laboratory members for sharing reagents, for constructive discussions, and for critical reading of the manuscript. Mark Schmitt and Gabriela Estepa are greatly appreciated for help with animal protocols and animal experiments. We appreciate the technical help of the members core facilities at the Salk Institute: Next Generation Sequencing, Integrated Genomics and Bioinformatics, Functional Genomics, Flow Cytometry, and Advanced Biophotonics. We appreciate the help of the Sanford Consortium Histology and Imaging Core facility for all tissue processing. N.Y. is currently supported by a training grant from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine and was supported by a Nomis Foundation fellowship and a Helmsley Foundation fellowship for nutritional genomics. I.M.V is an American Cancer Society Professor of Molecular Biology and holds the Irwin and Joan Jacobs Chair in Exemplary Life Science. This work was supported in part by NIH Grant R37AI048034, Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA014195-38, Ipsen, the H. N. and Frances C. Berger Foundation, and Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust Grant 2012-PG-MED002.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520110112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511(7511):543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding L, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imielinski M, et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150(6):1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon MC, Berns A. Mouse models for lung cancer. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(2):165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meuwissen R, Berns A. Mouse models for human lung cancer. Genes Dev. 2005;19(6):643–664. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim CF, et al. Mouse models of human non-small-cell lung cancer: Raising the bar. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:241–250. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gargiulo G, Serresi M, Cesaroni M, Hulsman D, van Lohuizen M. In vivo shRNA screens in solid tumors. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(12):2880–2902. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015;160(6):1246–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicent S, et al. Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) regulates KRAS-driven oncogenesis and senescence in mouse and human models. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3940–3952. doi: 10.1172/JCI44165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kool J, Berns A. High-throughput insertional mutagenesis screens in mice to identify oncogenic networks. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(6):389–399. doi: 10.1038/nrc2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann MB, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Mann KM. Sleeping Beauty mutagenesis: Exploiting forward genetic screens for cancer gene discovery. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;24:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudalska R, et al. In vivo RNAi screening identifies a mechanism of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20(10):1138–1146. doi: 10.1038/nm.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schramek D, et al. Direct in vivo RNAi screen unveils myosin IIa as a tumor suppressor of squamous cell carcinomas. Science. 2014;343(6168):309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1248627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondylis V, Tang Y, Fuchs F, Boutros M, Rabouille C. Identification of ER proteins involved in the functional organisation of the early secretory pathway in Drosophila cells by a targeted RNAi screen. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beronja S, et al. RNAi screens in mice identify physiological regulators of oncogenic growth. Nature. 2013;501(7466):185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(7):1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Y, et al. Reduced cell proliferation by IKK2 depletion in a mouse lung-cancer model. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(3):257–265, and erratum (2015) 17(4):532. doi: 10.1038/ncb2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15(24):3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji H, et al. LKB1 modulates lung cancer differentiation and metastasis. Nature. 2007;448(7155):807–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwanaga K, et al. Pten inactivation accelerates oncogenic K-ras-initiated tumorigenesis in a mouse model of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):1119–1127. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher GH, et al. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15(24):3249–3262. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: Bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(3):165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barquilla A, Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins: Therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo H, et al. Disruption of EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase leads to increased susceptibility to carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Cancer Res. 2006;66(14):7050–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petty A, et al. A small molecule agonist of EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits tumor cell migration in vitro and prostate cancer metastasis in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao H, Burnett E, Kinch M, Simon E, Wang B. Activation of EphA2 kinase suppresses integrin function and causes focal-adhesion-kinase dephosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(2):62–69. doi: 10.1038/35000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen AB, et al. Activation of the EGFR gene target EphA2 inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced cancer cell motility. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(3):283–293. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweet-Cordero A, et al. An oncogenic KRAS2 expression signature identified by cross-species gene-expression analysis. Nat Genet. 2005;37(1):48–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macrae M, et al. A conditional feedback loop regulates Ras activity through EphA2. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldser DM, et al. Stage-specific sensitivity to p53 restoration during lung cancer progression. Nature. 2010;468(7323):572–575. doi: 10.1038/nature09535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar MS, et al. The GATA2 transcriptional network is requisite for RAS oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. 2012;149(3):642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watnick RS, Cheng YN, Rangarajan A, Ince TA, Weinberg RA. Ras modulates Myc activity to repress thrombospondin-1 expression and increase tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):219–231. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amakye D, Jagani Z, Dorsch M. Unraveling the therapeutic potential of the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng JM, Curran T. The Hedgehog’s tale: Developing strategies for targeting cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(7):493–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sánchez-Rivera FJ, et al. Rapid modelling of cooperating genetic events in cancer through somatic genome editing. Nature. 2014;516(7531):428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature13906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amato KR, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of EPHA2 promotes apoptosis in NSCLC. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):2037–2049. doi: 10.1172/JCI72522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brantley-Sieders DM, et al. Impaired tumor microenvironment in EphA2-deficient mice inhibits tumor angiogenesis and metastatic progression. FASEB J. 2005;19(13):1884–1886. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4038fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brannan JM, et al. Expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 is increased in smokers and predicts poor survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(13):4423–4430. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishikawa M, et al. Higher expression of EphA2 and ephrin-A1 is related to favorable clinicopathological features in pathological stage I non-small cell lung carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(3):431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hafner C, et al. Differential gene expression of Eph receptors and ephrins in benign human tissues and cancers. Clin Chem. 2004;50(3):490–499. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miao H, et al. EphA2 mediates ligand-dependent inhibition and ligand-independent promotion of cell migration and invasion via a reciprocal regulatory loop with Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akada M, Harada K, Negishi M, Katoh H. EphB6 promotes anoikis by modulating EphA2 signaling. Cell Signal. 2014;26(12):2879–2884. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hiramoto-Yamaki N, et al. Ephexin4 and EphA2 mediate cell migration through a RhoG-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(3):461–477. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201005141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harada K, Hiramoto-Yamaki N, Negishi M, Katoh H. Ephexin4 and EphA2 mediate resistance to anoikis through RhoG and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(12):1701–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawai H, et al. Ephexin4-mediated promotion of cell migration and anoikis resistance is regulated by serine 897 phosphorylation of EphA2. FEBS Open Bio. 2013;3:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koshikawa N, et al. Proteolysis of EphA2 converts it from a tumor suppressor to an oncoprotein. Cancer Res. 2015;75(16):3327–3339. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugiyama N, et al. EphA2 cleavage by MT1-MMP triggers single cancer cell invasion via homotypic cell repulsion. J Cell Biol. 2013;201(3):467–484. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]