Significance

Modern contact mechanics was originally developed to describe adhesion to relatively stiff materials like rubber, but much softer sticky materials are ubiquitous in biology, medicine, engineering, and everyday consumer products. By studying adhesive contact between compliant gels and rigid objects, we demonstrate that soft materials adhere very differently than their stiffer counterparts. We find that the structure in the region of contact is governed by the same physics that sets the geometry of liquid droplets, even though the material is solid. Furthermore, adhesion can cause the local composition of a soft material to change, thus coupling to its thermodynamic properties. These findings may substantially change our understanding of the mechanics of soft contact.

Keywords: wetting, adhesion, soft matter, surface tension, phase separation

Abstract

In the classic theory of solid adhesion, surface energy drives deformation to increase contact area whereas bulk elasticity opposes it. Recently, solid surface stress has been shown also to play an important role in opposing deformation of soft materials. This suggests that the contact line in soft adhesion should mimic that of a liquid droplet, with a contact angle determined by surface tensions. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observe a contact angle of a soft silicone substrate on rigid silica spheres that depends on the surface functionalization but not the sphere size. However, to satisfy this wetting condition without a divergent elastic stress, the gel phase separates from its solvent near the contact line. This creates a four-phase contact zone with two additional contact lines hidden below the surface of the substrate. Whereas the geometries of these contact lines are independent of the size of the sphere, the volume of the phase-separated region is not, but rather depends on the indentation volume. These results indicate that theories of adhesion of soft gels need to account for both the compressibility of the gel network and a nonzero surface stress between the gel and its solvent.

Solid surfaces stick together to minimize their total surface energy. However, if the surfaces are not flat, they must conform to one another to make adhesive contact. Whether or not this contact can be made, and how effectively it can be made, are crucial questions in the study and development of solid adhesive materials (1, 2). These questions have wide-ranging technological consequence. With applications ranging from construction to medicine, and large-scale manufacturing to everyday sticky stuff, adhesive materials are ubiquitous in daily life. However, much remains unknown about the mechanics of solid adhesion, especially when the solids are very compliant (3–5). This limits our understanding and development of anything that relies on the mechanics of soft contact, including pressure-sensitive adhesives (6, 7), rubber friction (8), materials for soft robotics (9–12), and the mechanical characterization of soft materials, including living cells (13–17).

Adhesion is favorable whenever the adhesion energy, , is positive, where and are the surface energies of the free surfaces and is the interfacial energy in contact. When , the solids are driven to deform spontaneously to increase their area of contact, but at the cost of incurring elastic strain. The foundational and widely applied Johnson–Kendall–Roberts (JKR) theory of contact mechanics (18, 19) was the first to describe this competition between adhesion and elasticity. However, it was recently shown that the JKR theory does not accurately describe adhesive contact with soft materials because it does not account for an additional penalty against deformation due to solid surface stress, (4). Unlike a fluid, the surface stress of a solid is not always equal to its surface energy, γ. For solids, γ is the work required to create additional surface area by cleaving, whereas is the work needed to create additional surface area by stretching (20). In general, surface stresses overwhelm elastic response when the characteristic length scale of deformation is less than an elastocapillary length, L, given by the ratio of the surface stress to Young’s modulus, (21–25). This has an important implication for soft adhesion (4, 26–30): the geometry of the contact line between a rigid indenter and a soft substrate should be determined by a balance of surface stresses and surface energies, just as the Young–Dupré relation sets the contact angle of a fluid on a rigid solid (31). However, the structure of the contact zone in soft adhesion has not been examined experimentally.

In this article, we directly image the contact zone of rigid spheres adhered to compliant gels. Consistent with the dominance of surface stresses over bulk elastic stresses, we find that the surface of the soft substrate meets each sphere with a constant contact angle that depends on the sphere’s surface functionalization but not its size. To satisfy this wetting condition while avoiding a divergent elastic stress, the gel and its solvent phase separate near the contact line. The resulting four-phase contact zone includes two additional contact lines hidden below the liquid surface. The geometries of all three contact lines are independent of the size of the sphere and depend on the relevant surface energies and surface stresses. Surprisingly, these results demonstrate a finite surface stress between the gel and its solvent. The volume of the phase-separated contact zone depends on the indentation volume and the compressibility of the gel’s elastic network.

Structure of the Adhesive Contact Line

We study the contact between rigid glass spheres and compliant silicone gels. Glass spheres ranging in radius from 7 to 32 μm (Polysciences, 07668) are used as received or surface functionalized with 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyl-trichlorosilane (Sigma-Aldrich, 448931), as described in the Supporting Information. We prepare silicone gels by mixing liquid (1 Pa s) divinyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Gelest, DMS-V31) with a chemical cross-linker (Gelest, HMS-301) and catalyst (Gelest, SIP6831.2). The silicone mixture is degassed in vacuum, put into the appropriate experimental geometry, and cured at 68 C for 12–14 h. The resulting gel is an elastic network of cross-linked polymers swollen with free liquid of the same un- or partially-cross-linked polymer. The fraction of liquid PDMS in these gels is 62% by weight, measured by solvent extraction. The gel has a shear modulus of kPa, measured by bulk rheology. The Poisson ratio of the gel’s elastic network is , measured using a compression test in the rheometer as described in ref. 32. As this is an isotropic, elastic material, this gives a Young modulus kPa and a bulk modulus kPa. All rheology data are included in the Supporting Information.

We directly image the geometry of the contact between the gel and sphere using optical microscopy. To prepare the gel substrates, we deposit an 300-μm-thick layer of PDMS along the millimeter-wide edge of a standard microscope slide. The silicone surface is flat parallel to the edge of the slide and slightly curved in the orthogonal direction with a radius of curvature 700 μm. We distribute silica spheres sparsely on the surface of the gel and image only those spheres that adhere at the thickest part of the gel. Using an inverted optical microscope, we illuminate the sample with a low-N.A. condenser and image using a 40 (N.A. 0.60) air objective. Example images for fluorocarbon-functionalized and plain silica spheres having radii of about 18 μm are shown in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively. All of the images analyzed for this work are included in the Supporting Information. In all cases, the rigid particles spontaneously indent into the gel as they adhere. Plain silica spheres indent more deeply than fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres of the same size.

Fig. 1.

Contact angle measurements. (A and B) Side views of (A) an 18.2-μm-radius fluorocarbon-functionalized silica sphere and (B) a 17.7-μm-radius plain silica sphere, each adhered to an kPa silicone gel. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (C) Mapped profiles of the spheres in A and B overlaid, with fit circles drawn to outline each sphere’s position. The undeformed plane far from the adhered particles defines . (D) Close-up of the profiles in C superimposed on the raw data, focusing on the approach to contact. The constant curvature fits are overlaid as orange curves, as well as straight dashed lines indicating the measured contact angles. (E and F) Measured contact angle, θ, and measured curvature, , respectively, versus sphere radius for both the fluorocarbon-functionalized (blue triangles) and plain silica (red circles) spheres. Dashed lines indicate the mean values. Histograms of the measurements are shown at right, with mean and SD indicated.

To test whether surface stresses dominate over elasticity at the contact line, we measure the contact angle between the free surface of the gel and the sphere. Starting with the raw image data, we map the position of the dark edge in the images with 100-nm resolution using edge detection in MATLAB, as described in the Supporting Information. Example profiles for fluorocarbon-functionalized (blue points) and plain silica (red points) spheres are shown in Fig. 1C. We fit the central region of the profile with a circle to determine the position and radius of the sphere, indicated by the gray lines in Fig. 1C.

The approach to contact is qualitatively different for the two types of spheres: the substrate meets the plain spheres at a much shallower angle than the fluorocarbon-functionalized ones. We fit the substrate surface profile near the contact line to a surface of constant total curvature, which is the shape expected when surface stresses completely overwhelm elastic effects (31). The fitting procedure is described in the Supporting Information. Fit results for the profiles shown in Fig. 1C are plotted in Fig. 1D, zoomed in close to the contact line on one side. Note that we do not fit to the profile data within 1 μm of the contact line, because diffraction tends to round off sharp corners. The resulting contact angles and curvatures are plotted as a function of sphere size for both fluorocarbon-functionalized and plain spheres ranging in radius from 12 to 27 μm in Fig. 1 E and F.

The contact angle of the substrate on the sphere is independent of the sphere size, but depends on the sphere’s surface functionalization. The gel establishes a contact angle of with the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres, and with the plain spheres. We also see no size dependence of the curvature of the gel near the contact line, and little difference with surface functionalization: μm−1 and μm−1. Assuming that the surface tension of the solid is close to that of the liquid, 20 mN/m, these constant curvature values are comparable to the inverse of the elastocapillary length of the substrate μm−1.

For comparison, we measure the contact angle between the spheres and uncured PDMS liquid. See the Supporting Information for a description of this measurement, raw images, and a histogram of measured contact angles. In this case, the contact angles should be set by the surface energies through the classic Young–Dupré relation. We find that the plain silica spheres are completely engulfed by the silicone liquid, corresponding to a contact angle . On the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres, the uncured liquid makes a contact angle . These contact angles are also very close to what we measure for the silicone liquid on flat glass: on plain glass, and on fluorocarbon-functionalized flat glass.

The contact angles made by the silicone gel on the spheres are the same as the contact angles made by the silicone liquid. This suggests that the Young–Dupré relation governs the contact line of a soft adhesive. However, achieving the contact angle prescribed by Young–Dupré presents a serious difficulty for the gel’s elastic network, especially during contact with surfaces that demand total wetting. As the contact angle of the gel approaches zero, the tensile strain on the elastic network diverges. How does the gel satisfy the wetting condition without creating an elastic singularity?

Deformation of the Elastic Network

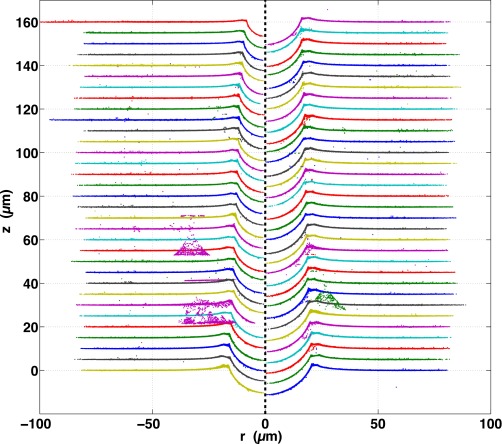

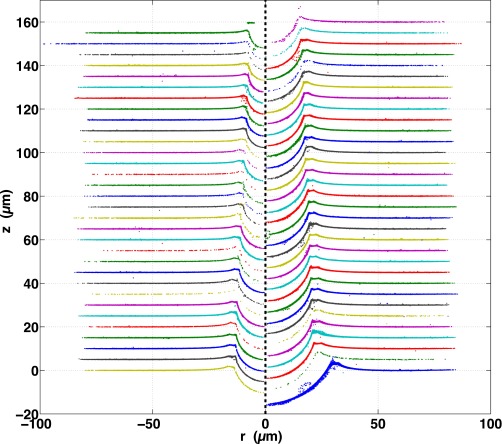

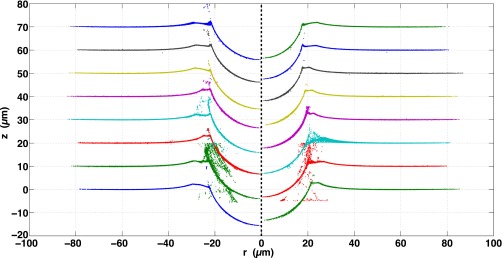

To quantify the deformation of the gel’s elastic network, we embed fluorescent tracers in the elastic network at the surface of the gel and image them using confocal microscopy. For this experiment, we prepare flat, 120-μm-thick, silicone substrates on glass coverslips by spin-coating. After curing, we adsorb 48-nm-diameter fluorescent spheres (Life Technologies, F-8795) from an aqueous suspension onto the PDMS. This procedure is identical to that described in ref. 32 except that we do not chemically modify the silicone surface. Then, following the procedure of ref. 4, we sprinkle silica spheres onto the substrates and map the surface of the deformed elastic network by locating the fluorescent makers in 3D from confocal microscope images (33). Examples of azimuthally collapsed deformation profiles for each type of sphere are shown in Fig. 2A. Confocal profiles for 146 spheres ranging from 7 to 32 μm in radius are included in the Supporting Information. We find that the dependence of indentation depth on particle size is consistent with our earlier study of the transition from elastic-dominated to capillary-dominated adhesion (4); these data and fits to theory are also included in the Supporting Information, Fig. S13.

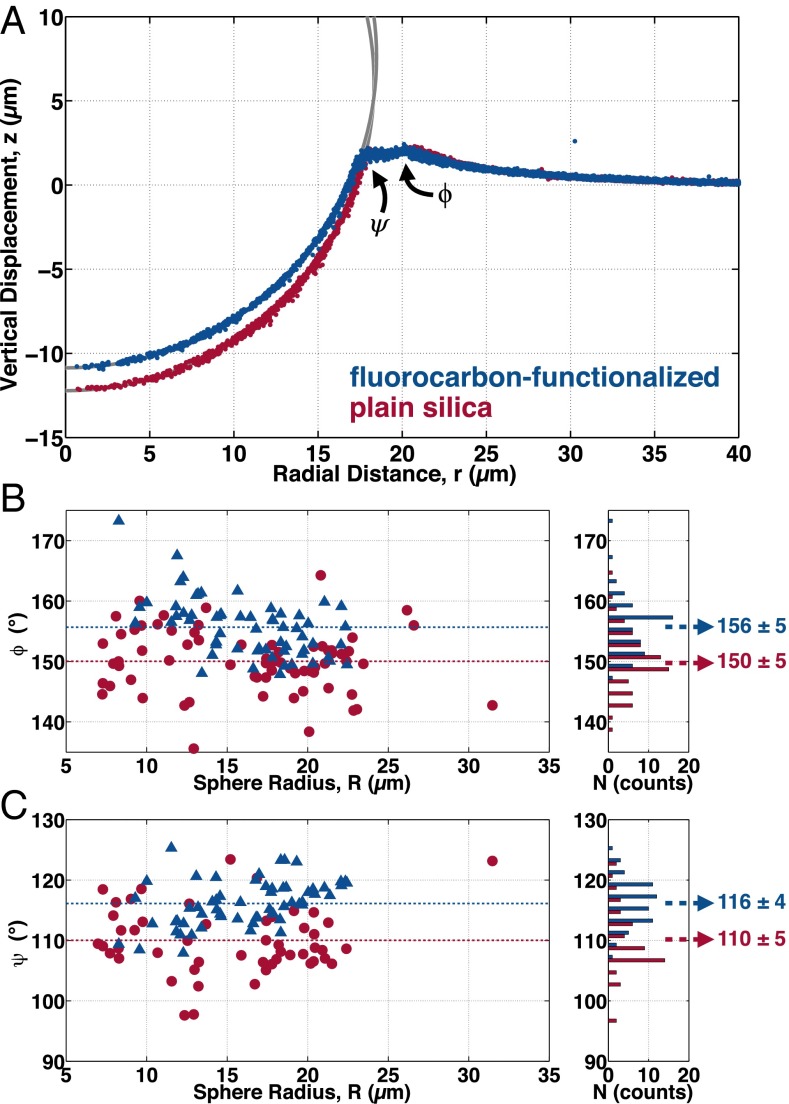

Fig. 2.

Structure of the gel’s elastic network near contact. (A) Confocal profiles of the surface of the silicone elastic network adhered to an 18.3-μm-radius plain silica sphere (red) and an 18.5-μm-radius fluorocarbon-functionalized sphere (blue). (B) Contact angle, ϕ, made by the elastic network as it abruptly changes direction during approach to contact. (C) Contact angle, ψ, made by the elastic network as it contacts the sphere. Both ϕ and ψ are plotted versus sphere radius for both the fluorocarbon-functionalized (blue triangles) and plain silica (red circles) spheres. Dashed lines indicate the mean contact angle. Histograms of the measured contact angles are shown at right, with mean and SD indicated.

As expected, the elastic network rises gradually toward contact from the far field and conforms to the surface of the spheres underneath the particles. However, the surface of elastic network in the contact zone (Fig. 2A) looks nothing like the free surface of the substrate (Fig. 1). Specifically, the elastic network does not rise smoothly to contact the sphere with the expected contact angle and curvature. Instead, it has a kink of angle ϕ a few micrometers from the sphere. Eventually the elastic network comes into contact with the sphere with an angle ψ well below the expected contact point. A series of control experiments, described in the Supporting Information, ruled out the possibility that the discrepancies between the structure of the contact zone in the bright-field and confocal experiments could be due to imaging artifacts. Just like the contact angle of the free surface θ (Fig. 1E), the angles ϕ and ψ are independent of sphere radius, as shown in Fig. 2 B and C.

Adhesion-Induced Phase Separation

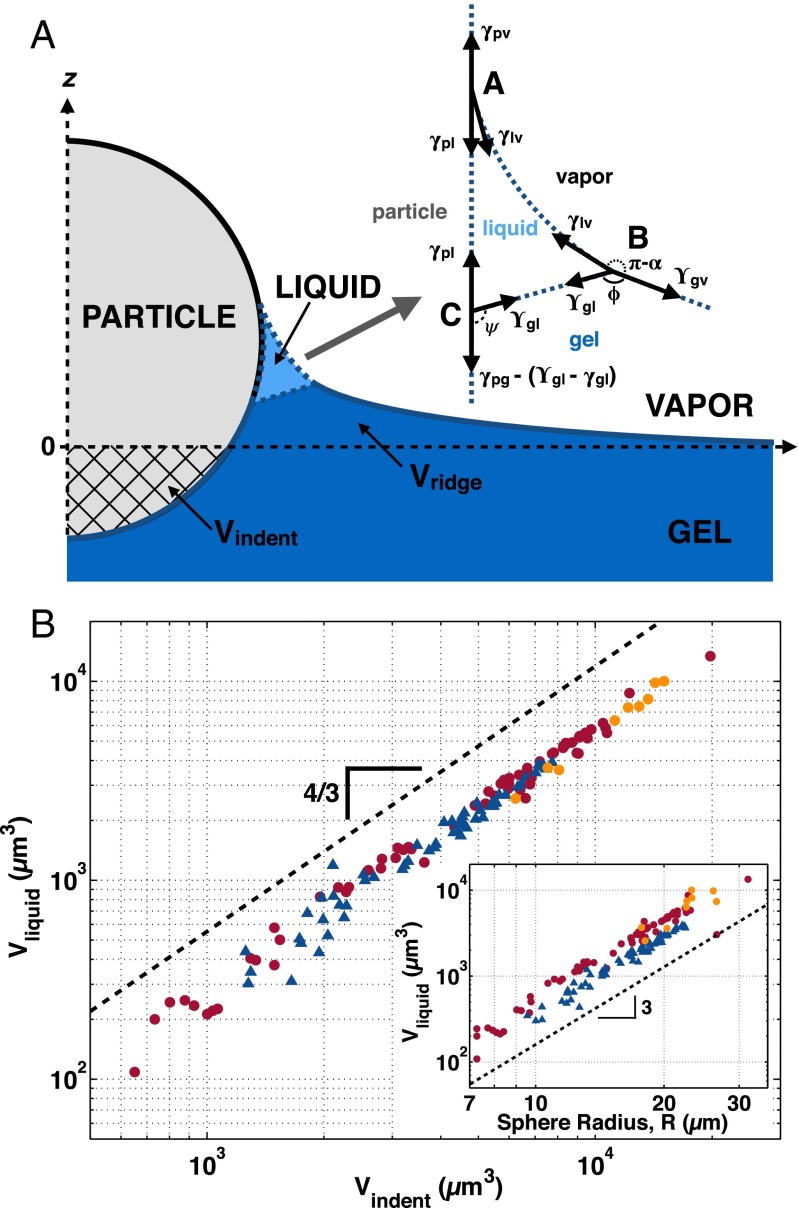

Comparison of the bright-field images in Fig. 1 A and B with the confocal images in Fig. 2A suggests that liquid PDMS fills the space between the elastic network and the free surface, as shown schematically in Fig. 3A. In this way, the fluid can satisfy the Young–Dupré wetting condition while the elastic network avoids an elastic singularity. This adhesion-induced phase separation makes the zone of adhesive contact between a soft gel and a rigid object more complex than in adhesion to stiffer single-phase solids. Instead of a single three-phase contact line, phase separation creates a four-phase contact zone in which air, silica, silicone liquid, and silicone gel meet, as shown in Fig. 3A. In addition to the standard contact line at A, the confocal experiments reveal two additional contact lines at B and C. The existence of particle-size-independent contact angles ϕ and ψ at these contact lines strongly indicates that their geometry is governed by surface stresses and/or surface energies, as indicated in Fig. 3A, Inset. The contact line at A is a conventional rigid solid–liquid–vapor contact line which satisfies the Young–Dupré relation, as discussed above. The contact line at B follows a Neumann triangle construction at this soft solid–liquid–vapor contact line, as in refs. 34, 35. Finally, we expect the contact line at C to be described by a modified Young–Dupré relation for a soft solid in contact with a rigid solid, as in ref. 4.

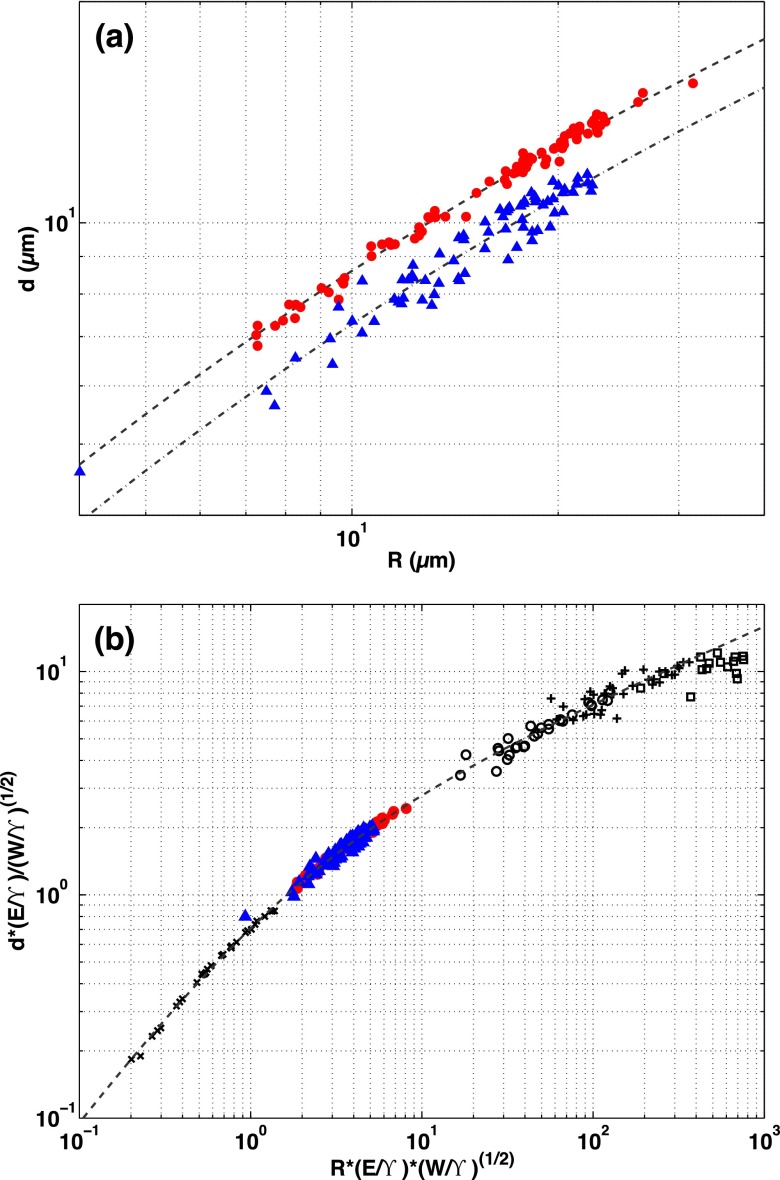

Fig. 3.

Structure and size of the four-phase contact zone. (A) Schematic of the four-phase contact zone. (Inset) Schematic of the surface tension balance at each of the contact lines A, B, and C. (B) Plot of the volume of phase-separated liquid, , vs. indented volume, , measured by integrating the confocal profiles. The data for plain spheres in air are plotted as red circles, for fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres in air as blue triangles, and for plain spheres under glycerol as orange circles. A dashed line of slope 4/3 is shown as a guide to the eye. (Inset) The same data plotted vs. sphere radius, with a dashed line of slope 3.

The structures of the contact lines at B and C therefore provide information about the relevant surface stresses and surface energies (20). For an ideal gel (36), the liquid phase dominates and the surface stress and surface energy of the gel are identical and equal to the surface tension of the solvent (36, 37). However, recent measurements of the surface stress of gels have sometimes differed significantly from the surface tension of their fluid phases (4, 34, 38, 39). If our silicone gel were ideal, we would expect the surface of the gel to be equivalent to the surface of its solvent, such that In that case, there would be no constraint on the contact angles, ψ or ϕ. However, the existence of well-defined, size-independent values of ψ and ϕ implies that . Furthermore, we observe that , implying that . This means that the particle has a preference for making contact with the pure liquid over the gel. This preference is only slightly changed by fluorocarbon functionalization of the particle surface.

At contact line B, the surface tension of the liquid must balance the surface stresses of the gel, and , through the Neumann construction. To fully determine all of the surface tensions, we also need to measure the difference in angle between the gel and the liquid free surfaces, α, as indicated in Fig. 3A, Inset. In principle, α should be measurable as a discontinuity in the free surface at B. However, our bright-field images do not reveal such a discontinuity (Fig. 1 and Supporting Information). This suggests that the angle α is small and cannot be resolved due to diffraction effects (as seen in Fig. 1D). Small values of α are expected when and/or are small. Simplifying the Neumann condition for , we obtain . Further, by expanding both the horizontal and vertical force balances at B for , we find that , which also results in small values of α for small ε.

Although we cannot measure α directly in these experiments, we can put a rough upper bound on its magnitude by combining our bright-field and confocal results for the geometry of the contact zone. These observations allow us to constrain α between 0 and 10. This bounds the values of the solid surface stresses such that and . More precise measurements of the free-surface profile at contact line B will be required for precise measurement of the solid surface stresses.

Surface stresses and energies fix the geometries of the corners of the phase-separated liquid region at A, B, and C, but this is not sufficient to determine its overall size, . Because the liquid is incompressible but the elastic network is not (40, 41), must equal the change in volume of the elastic network due to the adhesion of the sphere. We define as the volume occupied by the sphere below the plane of the undeformed silicone surface, and as the volume of the elastic network displaced above the undeformed surface, as indicated in Fig. 3A. Thus, we can measure from our confocal profiles as . We compute these volumes by numerical integration of the axisymmetric confocal profiles.

We plot vs. sphere radius in Fig. 3B, Inset. We see that the dependence of on sphere size differs for the different surface functionalizations, but scales approximately as . This suggests that may be related to volume, rather than surface effects. We find that all of the data collapse if we instead plot versus , as shown in the main panel of Fig. 3B. The volume of the phase-separated contact zone scales as a power law with exponent 4/3 over this range of indentation volumes. The more the elastic network is compressed by the spontaneous indentation of the particle, the larger the volume of incompressible liquid that phase-separates from the elastic network. This collapse is robust not only for the fluorocarbon-functionalized and plain silica spheres, but also after changing the balance of surface energies by covering the sphere and substrate with glycerol. It can even work when the system is out of equilibrium, as some of the glycerol-covered data points were not given enough time to equilibrate fully to their new indentation depth. Dimensionally, the prefactor for this power-law collapse must have dimensions of 1/[length]. Fitting to , we measure μm, which is about 10 times the elastocapillary length.

Conclusions

We have seen that during adhesion with a rigid object, a compliant gel phase-separates near the contact line to create a four-phase contact zone with three distinct contact lines. The total volume of the phase-separated region is set by the extent of indentation and the compressibility of the gel’s elastic network. The geometries of the contact lines are independent of the size of the particles and suggest that the gel–vapor–solid surface stress, , and the liquid–vapor surface tension, , are different, and that the solid surface stress between the gel and the liquid, , is nonzero.

These findings qualitatively change our understanding of the contact zone. This understanding of the geometry of contact and the balance of forces at work should inform both future theoretical work and engineering design of soft interfaces. Future studies will address adhesion-induced phase separation in different types of gels having varying compressibility of the elastic network. In many situations, a gel can be considered a single, homogeneous material. However, our results demonstrate that under extreme conditions––such as near a contact line––the nature of a gel as a multiphase material becomes important. This may have important implications not just for silicone materials, but also for materials like hydrogels, which have recently been the subject of significant research efforts (42–44). Because elastic networks in hydrogels can be much more compressible than the silicone gel studied here (40, 41), it is possible that they will be even more susceptible to phase separation during contact.

Silicone Gel Material and Characterization

We make soft, solid silicone gels from pure components to avoid any complications associated with additives that are common in commercial silicones. We combine silicone base: vinyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (DMS-V31, Gelest Inc) with a cross-linker: trimethylsiloxane terminated (25–35% methylhydrosiloxane)-dimethylsiloxane copolymer (HMS-301, Gelest Inc). The ratio of polymer to cross-linker determines the stiffness of the cured silicone gel. The reaction is catalyzed by a platinum-divinyltetramethyldisiloxane complex in xylene (SIP6831.2, Gelest Inc).

To make the silicone, we prepare two parts: Part A consists of the base with 0.05 wt % of the catalyst. Part B consists of the base with 10 wt % cross-linker. We mix parts A and B together in a ratio of 9:1 by weight. The parts are mixed together thoroughly and degassed in a vacuum. While the silicone is still liquid, we prepare the experimental substrates in the desired geometry as described in the main text, and then cure the silicone in an oven in air at 68° C for 12–14 h.

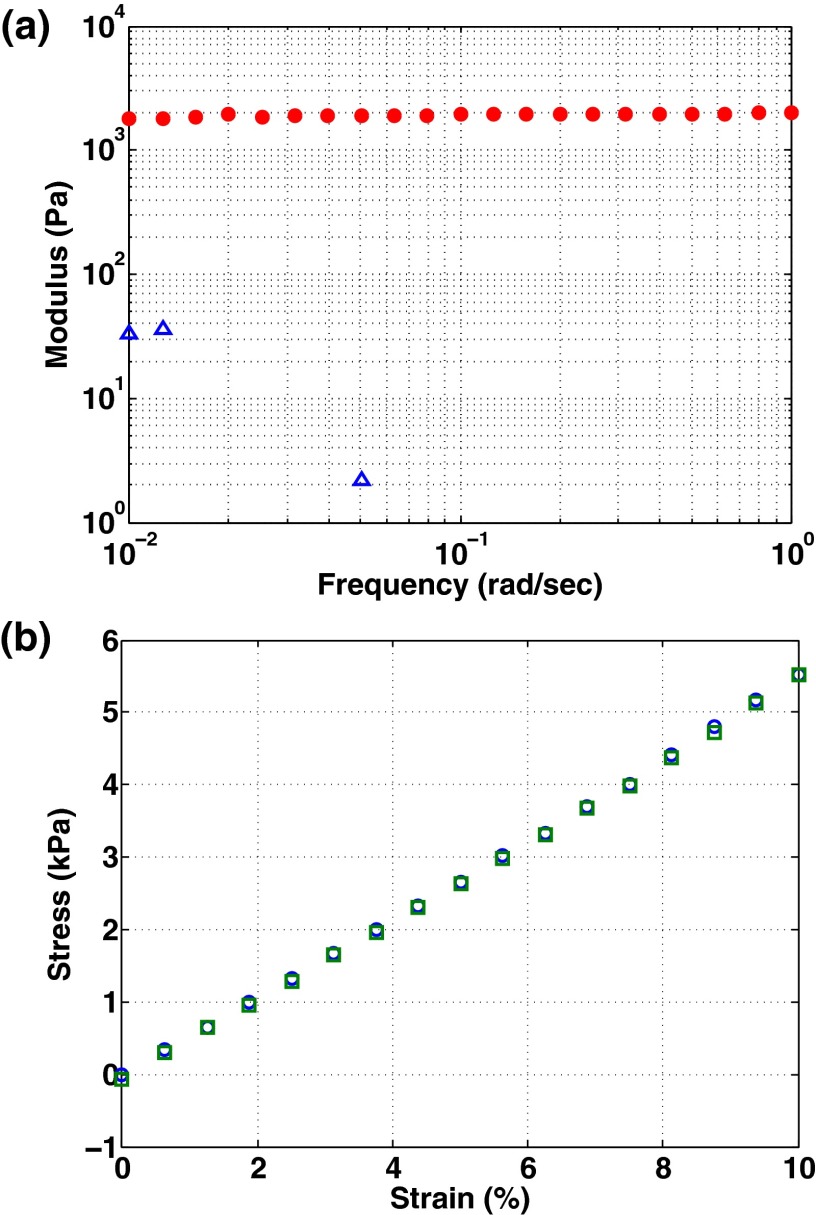

We measure the shear modulus and the Poisson ratio of the gel using bulk rheology performed on an ARES-LS1 rheometer. These data are plotted in Fig. S1. For the measurement of the Poisson ratio, we used the following relationship between compressive stress and strain, as given in ref. 32:

| [S1] |

Fig. S1.

Bulk rheology measurements of the PDMS gel. (A) Shear modulus (, red circles) and loss modulus (, blue triangles) vs. frequency. (B) Normal stress vs. applied strain, used for determining Poisson’s ratio as described in ref. 32. Blue circles and green squares represent two separate measurements on the same sample.

Because this is an isotropic, elastic material, there are only two independent elastic constants. We therefore use the standard relationships between the elastic constants to obtain the Young modulus, , and the bulk modulus, .

Fluorocarbon Functionalization of Silica Spheres

The silica spheres (Polysciences, 07668) were thoroughly cleaned by treating them in a piranha solution (70% concentrated sulfuric acid + 30% hydrogen peroxide) to remove all traces of organic residues from their surfaces. Following the piranha etch, the spheres were repeatedly washed with deionized water and dried in a hot air oven. Finally, the spheres were further cleaned with oxygen plasma.

The cleaned spheres were treated with vapors of 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane (Sigma-Aldrich, 448931) in a home-built apparatus as described below. A few drops of the silane were evenly deposited on a piece of filter paper that was placed on the perforated platform of a porcelain Büchner funnel. Dry air was used as a carrier gas that transported the vapor of the silane that reacted with the silica particles (placed inside a cone-shaped filter paper) in the upper part of the funnel for 30 min. Another filter paper was placed atop the silane-infused filter paper to capture any gel particles formed by hydrolysis and condensation of the silane in the vapor phase. During the entire process, the open end of the funnel was covered with a polystyrene lid.

Bright-Field Image Profile Mapping

We identify the edge of the sphere and/or substrate using an iterative procedure on bright-field images using intensity gradients. With this method, we can map bright/dark edges in images to a precision of about 100 nm, determined by measuring the noise floor of the map of an undeformed surface. We calibrate the camera pixel size for each experiment using a stage micrometer.

Fig. S2 shows the image processing steps used in profile mapping. Here, for consistency we show the same example sphere from Fig. 1B of the main text, cropped to show only the area close to the sphere. The full field of view is much wider than this, as shown in Fig. S3, which is essential for determining the height of the undeformed surface, described below.

Fig. S2.

Profile mapping procedure and result for the same plain silica sphere example as shown in Fig. 1B of the main text. (A) Raw bright-field image. (B) Smoothed image. (C) Gradient of smoothed image. (D) Raw image with mapped profile overlaid. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

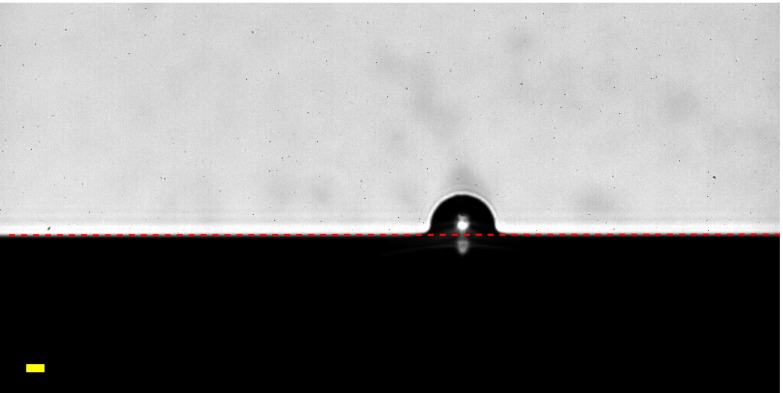

Fig. S3.

Full-field-of-view bright-field image of the same plain silica sphere example as shown in Fig. 1B of the main text, with the extrapolated position of the original, undeformed surface shown as a dashed red line. We determine the coordinates of the undeformed plane by fitting to the measured profile of the gel surface far from the sphere. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

We start by slightly smoothing the raw bright-field image, shown in Fig. S2A, using a 3-by-3 pixel averaging filter to reduce noise in the edge finding. This produces a smoothed image, as shown in Fig. S2B. We then convert this to a map of the gradient of the image using the MATLAB built-in function imgradient(), as shown in Fig. S2C.

Finally, we map the edge profile by walking the curve that represents the image gradient maximum as measured along the direction normal to the profile. Given two user-determined starting points (which are later discarded), the algorithm first extends the profile linearly in the direction of the last two profile points by n more points spaced by a step distance . It then refines the location of these extended points by sampling the gradient image a length L pixels on either side of the extended points normal to the line of those points, fitting a Gaussian to the gradient profile, and shifting each point to a new, refined location corresponding to the peak of the fit Gaussian. The process then iterates, extending the profile again based on the line between the last two refined points, and continues until the edge of the image is reached or the profile is unable to be fit for some reason. The final measured profile, superimposed on the original raw image, is shown for the example in Fig. S2D.

In principle, these profile points could be further refined by resampling the gradient normal to the derivative of the refined points, but in practice we find that by setting small n and the profile is well-mapped by a single walk of the image. For the work reported here, we used , pixels, and pixels.

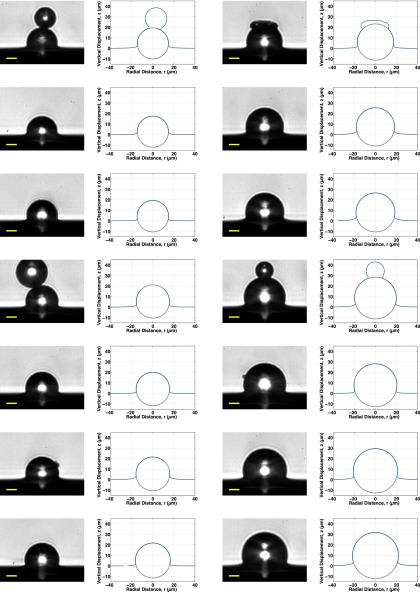

All 48 profiles measured for this work are plotted next to their corresponding raw images (both zoomed in to the region around each sphere) and shown, respectively, in Fig. S4 for the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres, Figs. S5 and S6 for the plain silica spheres, and Fig. S7 for the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres that were trapped in PDMS before curing.

Fig. S4.

All 14 bright-field raw images (Left) and measured profiles (Right) of fluorocarbon-functionalized silica spheres adhered to silicone gel substrates. Gray circles show measured sphere size and position. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Fig. S5.

Smallest 10 bright-field raw images (Left) and measured profiles (Right) of plain silica spheres adhered to silicone gel substrates. Gray circles show measured sphere size and position. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Fig. S6.

Largest nine bright-field raw images (Left) and measured profiles (Right) of plain silica spheres adhered to silicone gel substrates. Gray circles show measured sphere size and position. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Fig. S7.

All 15 bright-field raw images (Left) and measured profiles (Right) of fluorocarbon-functionalized silica spheres that were sprinkled onto liquid silicone with cross-linker, allowed to establish their equilibrium positions as prescribed by the balance of surface tensions at the contact line, and subsequently trapped as the PDMS cured. Gray circles show measured sphere size and position. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Determining the Position of the Undeformed Surface

To determine the real profile deformation height, we need to determine the position of the undeformed surface before the sphere stuck to it. We do this by assuming that the measured profile far from the sphere is in its original, undeformed position. Although the substrates are basically flat, we fit the measured profile far from the sphere to a parabola to account for any possible curvature of the surface. We then extrapolate this measurement over the entire length of the measured image profile, and subtract to zero the profile. A full-field-of-view bright-field image is shown in Fig. S3, with the fit and extrapolated undeformed surface profile plotted as a red dashed line. For consistency, this is again the same plain sphere as in the above examples and in Fig. 1B in the main text.

Measuring Contact Angles of Spheres with Uncured PDMS

To measure the contact angle between the spheres and the liquid PDMS, we prepared slide-edge substrates as described in the main text, but sprinkled the silica spheres onto the PDMS prior to curing the silicone. Because the curing time is much longer than the time for the spheres to reach their equilibrium position at the fluid–air interface, we can trap silica spheres in their equilibrium position with the liquid governed solely by Young–Dupré wetting. We cured these substrates upside down, so that any sedimentation that might occur before solidification of the PDMS would tend to cause the spheres to drift toward the peak of the PDMS ridge, the optimal position for imaging. We then image the trapped spheres in the same way we imaged the adhered spheres.

Plain spheres immediately disappeared below the liquid surface, indicating a contact angle (total wetting). Upon curing, plain spheres remained completely embedded in the cured PDMS.

The fluorocarbon-functionalized silica spheres, on the other hand, established a constant contact angle with the liquid silicone surface. A typical image of a trapped fluorocarbon-functionalized sphere is shown in Fig. S8A. All bright-field images of the embedded fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres are included in Fig. S7.

Fig. S8.

(A) Trapped fluorocarbon-functionalized silica sphere. The measured surface profile is plotted as blue dots and the fit to the undeformed surface away from the sphere is plotted as a red dashed line. We measure the sphere size and position by fitting the part of the sphere that remained above the PDMS surface to a circle, shown in orange. Because the surrounding material is flat, the contact angle is simply the angle between the undeformed surface and the sphere. (B) Histogram of contact angles established by fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres in uncured silicone, as in A, with mean and SD indicated.

To measure the contact angle of the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres, we map the deformation profile as described above and fit a circle to the spherical cap part of the profile to measure the radius, R, and position of the sphere. Because the surrounding PDMS surface is flat, the size and indentation depth of the sphere are sufficient to calculate the angle at which the plane intersects the sphere, which is the contact angle. The contact angle between the flat surface and the sphere is given by the geometric relationship , where d is the indentation depth, defined as the distance from the surface to the bottom of the sphere. We thus determine the contact angle of liquid silicone on the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres to be , as shown by the histogram in Fig. S8B.

We show a zoomed-in example of an embedded sphere in Fig. S8A, with the measured profile plotted as blue dots, the fit sphere position as an orange circle, and the fit undeformed (flat) surface as a red dashed line. In addition to providing a measurement of the equilibrium contact angle between the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres and the silicone, these profiles also reveal a limitation of the profile mapping in the case where there are sharp corners in the profile. Although the flat surface meets the sphere at a fixed, sharp angle, diffraction rounds out the transition from the silicone surface onto the sphere for about μm on either side of the intersection. This means that any time there may be a discontinuity in the actual surface profile, the measured profile may be inaccurate within about a micrometer of the intersection.

Measuring Contact Angles of Spheres with PDMS Gels by Constant-Curvature Fitting

To measure the contact angle between the adhered spheres and the PDMS surface, we fit the measured profiles in the vicinity of the contact line point with a shape that is the intersection of two surfaces of constant total curvature that meet at the contact line.

The sphere, by definition, has a surface of total curvature , although we allow this to be a fit parameter. The silicone does not necessarily have a constant curvature everywhere, but we find that the measured profile is fit well by a constant-curvature surface near the contact line. This is expected as capillary forces, which require a surface of constant total curvature, should dominate over elastic forces over short length scales.

An axially symmetric surface, , with constant total curvature κ satisfies the set of ordinary differential equations (45):

| [S2] |

| [S3] |

| [S4] |

Here θ is the angle of the surface from horizontal, and s is the arc length along the curve . We can therefore calculate a constant-curvature profile by specifying κ and the initial conditions for , , and θ at the contact line, and integrating these equations numerically.

We fit for six parameters in total: the curvature and orientation of each of the two constant curvature surfaces, and the coordinates of the contact point where the two surfaces meet. Because diffraction rounds out sharp corners, as described above, we exclude from the fit any points within 1-μm radial distance of the current-best-fit contact point. The domain of constant curvature ranges from about 2–4 μm.

We show the results of these fits for the same example spheres and profiles as in Fig. 1D of the main text. Fig. 1D (Left) shows the fit results for the fluorocarbon-functionalized sphere, with a fit contact angle of 55.3°. This example is close to the center of the measured distribution of contact angles for fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres. Note that the profile mapping rounded out this corner, as we observed with the embedded spheres.

Fig. 1D (Right) shows the fits for the plain silica sphere. This example happens to be an outlier in the distribution, with a measured contact angle of 14.1°. However, it is still apparent that the contact angle is significantly less than that of the fluorocarbon-functionalized sphere.

Control Experiments for Imaging Artifacts

It is possible that the index of refraction difference at the PDMS–air interface results in some distortion of the measured surface profile, especially as the interface tilts more steeply close to the sphere. To understand the impact of this optical effect on our observations, we conducted two important control experiments. First, we coated the surface of plain silica spheres with fluorescent markers before making adhesive contact. Thus, we were able to simultaneously image the elastic network and the sphere surface. These data clearly show that the elastic network does not conform to the sphere near the contact zone. These profiles are all shown in Fig. S11. Second, we imaged the deformation profile immediately after immersing a sphere and substrate with glycerol. This significantly reduced the index of refraction contrast at the free surface, but made no significant changes to the observed profile. These profiles are all shown in Fig. S12. Therefore, the discrepancies between the bright-field profiles of the gel surface and the confocal profiles of the elastic network are robust.

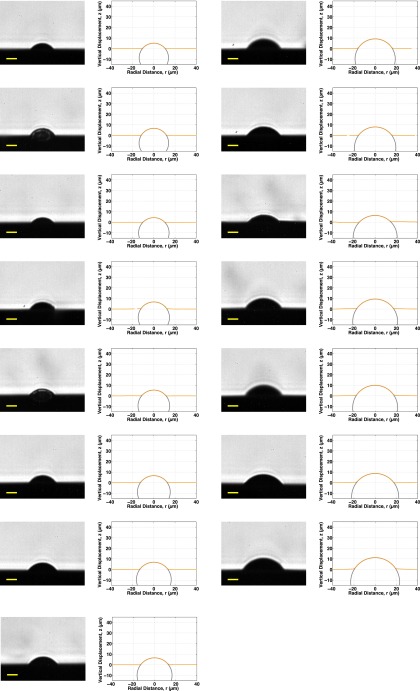

All 154 Confocal Profiles from This Work, plus 10 Repeats with Glycerol Above Instead

The Supporting Information includes all confocal profiles used in this work.

Fig. S9 shows all 66 confocal profiles for all fluorocarbon-functionalized silica spheres, ranging in size from 8.3 to 22.4 μm. All of these are included in the d vs. R plots of Fig. S13. All profiles with a sufficient density of points for numerical integration are included in the vs. plot of Fig. 3B of the main text. Some spheres had clumps of fluorescent particles on the substrate that resulted in extraneous mapped “points” below the profile; these were not included in any numerical integration.

Fig. S9.

All 66 fluorocarbon-functionalized silica sphere confocal profiles, ranging in size from 8.3 to 22.4 μm. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Fig. S10 shows all 65 confocal profiles for plain silica spheres, ranging in size from 7.0 to 31.5 μm. All of these are included in the d vs. R plots of Fig. S13. All profiles with a sufficient density of points for numerical integration are included in the vs. plot of Fig. 3B of the main text.

Fig. S10.

All 65 plain silica sphere confocal profiles, ranging in size from 7.0 to 31.5 μm. Spheres are arranged from smallest to largest, top to bottom, left to right.

Fig. S11 shows 16 confocal profiles for plain silica spheres that have been sparsely coated with the same 40-nm fluorescent beads as the silicone elastic network, ranging in size from 17.7 to 23.2 μm. All of these are included in the d vs. R plots of Fig. S13. All profiles with a sufficient density of points for numerical integration and without extraneous points from clumping are included in the vs. plot of Fig. 3B of the main text.

Fig. S11.

Confocal profiles for all 16 plain silica spheres whose surfaces were marked with the same 40-nm-diameter fluorescent beads as the PDMS elastic network, ranging in size from 17.7 to 23.2 μm. Clumping of the fluorescent spheres on some of the spheres resulted in a couple of noisy profiles.

Fig. S12 shows repeat profiles of 10 of the glowing spheres from Fig. S11, but with glycerol added on top of the sphere and surrounding PDMS where previously there had been air. The addition of glycerol changes the balance of surface energies, causing the spheres to shift toward a new equilibrium spontaneous indentation depth. However, these were not given time to fully equilibrate to their new depth, so they represent intermediate states between their initial and final positions.

Fig. S12.

Confocal profiles for 10 of the plain silica spheres from Fig. S11, whose surfaces were marked with the same 40-nm-diameter fluorescent beads as the PDMS elastic network. After adhesion to the PDMS substrates, the spheres were covered with glycerol. This substantially reduces the index mismatch compared with having air above the silicone surface, allowing us to be confident that imaging artifacts are not responsible for the measured shape of the elastic network surface. The addition of glycerol also changes the surface tension and adhesion energy, so these are not included in the d vs. R plots. These spheres range in size from 17.7 to 23.2 μm. Clumping of the fluorescent spheres on some of the spheres resulted in a couple of noisy profiles.

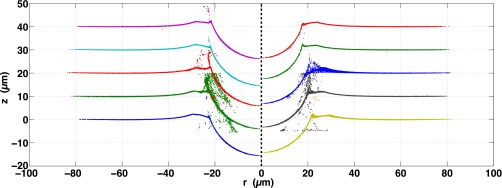

Dependence of Indentation on Particle Size

From the confocal experiments, we measure the indentation depth, d, as a function of particle radius, R, for both plain and fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres. We plot d vs. R for both sphere types in Fig. S13A. As expected, the indentation increases with particle size, and the plain spheres indent more deeply than the fluorocarbon-functionalized ones, consistent with our observation that the silicone substrates are more highly wetting on the plain spheres. There is somewhat more scatter in the data from the fluorocarbon-functionalized spheres, likely due to imperfect surface functionalization on some spheres.

Fig. S13.

(A) Indentation depth, d, vs. particle radius, R, for plain silica (red circles) and fluorocarbon-functionalized (blue triangles) spheres. Dashed and dot-dashed lines show fits to Eq. S5 for each data set. (B) Dimensionless indentation depth, , vs. dimensionless particle radius, , including all data from this work (same symbols as above) and all data from our earlier work (4) (black open symbols). Dashed line is the theory, expressed in Eq. S5.

These data can be collapsed by our previous scaling theory (4), which balances elasticity, adhesion, and surface tension to give an implicit relation for the indentation with particle size:

| [S5] |

Here, , where , and , where .

Fitting the data to this relation yields μm and for the plain spheres, and μm and for the fluorocarbon-functionalized ones. We use these fit values to collapse the d vs. R data onto the dimensionless master curve described by Eq. S5, and set these collapsed data in the context of our previous work (4) in Fig. S13B.

In the case of partial wetting, we can express the contact angle in the limit of in terms of the ratio of the adhesion energy to the surface tension, (refs. 4, 26). Using the results reported above from fitting to Eq. S5, the elastocapillary theory (4) would predict contact angles for the plain and fluorocarbon-functionalized silica spheres of and , respectively. These values are substantially larger than the contact angles we measure directly from the bright-field experiments, especially for the plain spheres. This discrepancy may be a consequence of the simplifying assumptions about the geometry of the contact zone made by the scaling argument used to derive Eq. S5 (4).

Acknowledgments

We thank Manjari Randeria and Ross Bauer for help with sample preparation, and Dominic Vella for useful discussions and for help with the MATLAB code for the constant-curvature analyses. We acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (CBET-1236086). R.W.S. also received funding from the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.A. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514378112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Johnson K. Contact Mechanics. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creton C, Papon E. Materials science of adhesives: How to bond things together. MRS Bull. 2003;28(6):419–421. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shull K, Ahn D, Chen W, Flanigan C, Crosby A. Axisymmetric adhesion tests of soft materials. Macromol Chem Phys. 1998;199(4):489–511. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Style RW, Hyland C, Boltyanskiy R, Wettlaufer JS, Dufresne ER. Surface tension and contact with soft elastic solids. Nat. 2013;4:2728. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastewka L, Robbins MO. Contact between rough surfaces and a criterion for macroscopic adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(9):3298–3303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320846111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosby A, Shull K. Adhesive failure analysis of pressure-sensitive adhesives. J Polym Sci, B, Polym Phys. 1999;37(24):3455–3472. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creton C. Pressure-sensitive adhesives: An introductory course. MRS Bull. 2003;28(6):434–439. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persson B. Theory of rubber friction and contact mechanics. J Chem Phys. 2001;115(8):3840–3861. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao I, Yang F. Stiffness and contact mechanics for soft fingers in grasping and manipulation. IEEE Trans Robot Autom. 2004;20(1):132–135. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, et al. 2007. Whole body adhesion: Hierarchical, directional and distributed control of adhesive forces for a climbing robot. 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (IEEE, Rome), pp 1268–1273.

- 11.Martinez RV, et al. Robotic tentacles with three-dimensional mobility based on flexible elastomers. Adv Mater. 2013;25(2):205–212. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Laschi C, Trimmer B. Soft robotics: A bioinspired evolution in robotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(5):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mowery C, Crosby A, Ahn D, Shull K. Adhesion of thermally reversible gels to solid surfaces. Langmuir. 1997;13(23):6101–6107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Vliet K, Bao G, Suresh S. The biomechanics toolbox: Experimental approaches for living cells and biomolecules. Acta Mater. 2003;51(19):5881–5905. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suresh S. Biomechanics and biophysics of cancer cells. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(4):413–438. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li QS, Lee GYH, Ong CN, Lim CT. AFM indentation study of breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374(4):609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Rodriguez D, Guevorkian K, Douezan S, Brochard-Wyart F. Soft matter models of developing tissues and tumors. Science. 2012;338(6109):910–917. doi: 10.1126/science.1226418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson K, Kendall K, Roberts A. Surface energy and contact of elastic solids. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1971;324(1558):301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maugis D. Extension of the Johnson-Kendall-Roberts theory of the elastic contact of spheres to large contact radii. Langmuir. 1995;11(2):679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cammarata RC, Sieradzki K. Surface and interface stresses. Annu Rev Mater Sci. 1994;24(1):215–234. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long D, Ajdari A, Leibler L. Static and dynamic wetting properties of thin rubber films. Langmuir. 1996;12(21):5221–5230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerison ER, Xu Y, Wilen LA, Dufresne ER. Deformation of an elastic substrate by a three-phase contact line. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106(18):186103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.186103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagota A, Paretkar D, Ghatak A. Surface-tension-induced flattening of a nearly plane elastic solid. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2012;85(5):051602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.85.051602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paretkar D, Xu X, Hui CY, Jagota A. Flattening of a patterned compliant solid by surface stress. Soft Matter. 2014;10(23):4084–4090. doi: 10.1039/c3sm52891j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mora S, Phou T, Fromental JM, Pismen LM, Pomeau Y. Capillarity driven instability of a soft solid. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105(21):214301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.214301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X, Jagota A, Hui CY. Effects of surface tension on the adhesive contact of a rigid sphere to a compliant substrate. Soft Matter. 2014;10(26):4625–4632. doi: 10.1039/c4sm00216d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T, Jagota A, Hui CY. Adhesive contact of a rigid circular cylinder to a soft elastic substrate–the role of surface tension. Soft Matter. 2015;11(19):3844–3851. doi: 10.1039/c5sm00008d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao Z, Stevens MJ, Dobrynin AV. Adhesion and wetting of nanoparticles on soft surfaces. Macromolecules. 2014;47(9):3203–3209. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salez T, Benzaquen M, Raphaël É. From adhesion to wetting of a soft particle. Soft Matter. 2013;9(45):10699–10704. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hui CY, Liu T, Salez T, Raphael E, Jagota A. Indentation of a rigid sphere into an elastic substrate with surface tension and adhesion. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2015;471(2175):20140727. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2014.0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Gennes PG, Brochard-Wyart F, Quéré D. Capillarity and Wetting Phenomena: Drops, Bubbles, Pearls, Waves. Springer Science & Business Media; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Style RW, et al. Traction force microscopy in physics and biology. Soft Matter. 2014;10(23):4047–4055. doi: 10.1039/c4sm00264d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Kilfoil ML. Accurate detection and complete tracking of large populations of features in three dimensions. Opt Express. 2009;17(6):4685–4704. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.004685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Style RW, et al. Universal deformation of soft substrates near a contact line and the direct measurement of solid surface stresses. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110(6):066103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.066103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lubbers LA, et al. Drops on soft solids: Free energy and double transition of contact angles. J Fluid Mech. 2014;747:R1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui CY, Jagota A. Surface tension, surface energy, and chemical potential due to their difference. Langmuir. 2013;29(36):11310–11316. doi: 10.1021/la400937r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuttleworth R. The surface tension of solids. Proc Phys Soc A. 1950;63(5):444–457. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadermann N, Hui CY, Jagota A. Solid surface tension measured by a liquid drop under a solid film. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):10541–10545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakrabarti A, Chaudhury MK. Direct measurement of the surface tension of a soft elastic hydrogel: exploration of elastocapillary instability in adhesion. Langmuir. 2013;29(23):6926–6935. doi: 10.1021/la401115j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geissler E, Hecht A. The Poisson ratio in polymer gels. Macromolecules. 1980;13(5):1276–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai S, Hu Y, Zhao X, Suo Z. Poroelasticity of a covalently crosslinked alginate hydrogel under compression. J Appl Phys. 2010;108(11):113514-1–113514-8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem Rev. 2001;101(7):1869–1879. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: Scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun JY, et al. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature. 2012;489(7414):133–136. doi: 10.1038/nature11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Río OI, Neumann AW. Axisymmetric drop shape analysis: Computational methods for the measurement of interfacial properties from the shape and dimensions of pendant and sessile drops. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1997;196(2):136–147. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1997.5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]