Significance

Quantum spin liquids are exotic insulators in which the electron’s spin, charge, and fermionic statistics are carried by separate excitations. They have received attention for their potential as a quantum memory and as a parent state for high-temperature superconductivity. A key principle guiding the search for experimental candidate materials is the absence of conventional order in insulators at “fractional” electron filling. Previous results established what constitutes fractional filling, but assumed symmetries that are typically not respected in real materials or considered only simple lattices. Here, assuming only physical symmetries we establish filling conditions for all 230 space groups. This should aid in the search for quantum spin liquids and topological semimetals.

Keywords: quantum spin liquids, spin-orbit coupling, Hastings–Oshikawa–Lieb–Schultz–Mattis theorem, nonsymmorphic space groups, nonperturbative arguments

Abstract

We determine conditions on the filling of electrons in a crystalline lattice to obtain the equivalent of a band insulator—a gapped insulator with neither symmetry breaking nor fractionalized excitations. We allow for strong interactions, which precludes a free particle description. Previous approaches that extend the Lieb–Schultz–Mattis argument invoked spin conservation in an essential way and cannot be applied to the physically interesting case of spin-orbit coupled systems. Here we introduce two approaches: The first one is an entanglement-based scheme, and the second one studies the system on an appropriate flat “Bieberbach” manifold to obtain the filling conditions for all 230 space groups. These approaches assume only time reversal rather than spin rotation invariance. The results depend crucially on whether the crystal symmetry is symmorphic. Our results clarify when one may infer the existence of an exotic ground state based on the absence of order, and we point out applications to experimentally realized materials. Extensions to new situations involving purely spin models are also mentioned.

Insulating states of matter arise, in clean systems, as a result of a commensuration between particle density and a crystalline lattice or a magnetic field. Mott insulators are a particularly interesting class. Their low energy physics are captured by a spin model with an odd number of spin- moments in the unit cell. A powerful result due to Lieb et al. (1) in 1D, later extended to higher dimensions by Oshikawa (2), Hastings (3), and Affleck (4), holds that if all symmetries remain unbroken, an insulating ground state must be “exotic”—for example, a Luttinger liquid in 1D or a quantum spin liquid in higher dimensions, both of which have fractional “spinon” excitations. These exotic states cannot be represented as simple product states as a consequence of their long-ranged entanglement.

This constraint, which we collectively refer to as Hastings–Oshikawa–Lieb–Schultz–Mattis (HOLSM), has experimental consequences. Indeed, no sign of magnetic or spatial symmetry breaking is observed down to temperatures orders of magnitude below the intrinsic energy scales in certain materials (5), including the quasi-2D Mott insulators κ-(BEDT-TTF)2 Cu2(CN)3, Pd(dmit)2, and Herbertsmithite ZnCu3(OH)6 Cl2, as well as the 3D Mott insulator Na4 Ir3 O8. Hence if we can apply HOLSM to these systems, a strong case is made for an exotic ground state (assuming that the effects of disorder can be ignored). However, HOLSM invokes spin rotation invariance in an essential way, which is typically broken in real materials due to spin-orbit coupling (SOC). These effects are not small: Herbertsmithite has Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya terms thought to be on the order of 10% of the Heisenberg coupling (6, 7). In the antiferromagnetic hyperkagome compound Na4Ir3O8, the physics are even dominated by SOC effects and charge fluctuation is significant (5). Physically, the only exact symmetries are time reversal (TR) and the crystal symmetries and charge conservation that allow us to define the electron filling. Can HOLSM be extended to this physically more realistic situation?

In this work we show that it indeed can, although entirely different theoretical approaches are needed. We introduce two methods that, like the flux-threading arguments of HOLSM, are nonperturbative, but differ from them in that conservation of spin is not assumed. The first one is an entanglement-based approach that allows us to prove that symmetric, gapped, and short-range entangled insulators—the interacting analog of band insulators—are allowed only at even integer fillings . For brevity we refer to such insulators as symmetric short-range entangled (“sym-SRE”) states. If a spin-orbit coupled insulator at odd filling is TR symmetric, its ground state must, in a precise sense, be exotic. A corollary is that, at odd integer fillings, Mott insulating phases must either break a symmetry or have a ground state degeneracy on certain geometries due to other, more exotic, mechanisms. A special case of this result for 1D spin models was previously discussed in ref. 8. Here we extend it to higher dimensions and allow for charge fluctuations.

This constraint on filling arises even when translations are the only spatial symmetries. What if additional symmetries are present, such as the 230 space groups of 3D crystals? It turns out that additional constraints appear only for the nonsymmorphic (NS) space groups, where the minimal positive filling at which a sym-SRE insulator can arise turns out to be at least 4. Earlier results on noninteracting band structures (9) pointed out that in NS crystals there are required band touchings leading to larger minimal fillings. In refs. 10 and 11 this was generalized to interacting systems, using flux threading arguments. However, similar to the HOLSM arguments, these need to assume spin rotation invariance and typically do not lead to useful constraints in its absence. Our argument allows both for strong interactions and for broken spin rotation invariance, while preserving TR symmetry.

The best bounds of are obtained using the second approach, by defining the system on a closed manifold that is locally flat and hence is locally indistinguishable from the Euclidean space (Bieberbach spaces). These spaces are generalizations of the torus, where instead of identifying points related by translations, one uses NS elements (glide planes or screw axes, which combine a fractional lattice translation with a reflection or rotation) to obtain a compact manifold. By exposing an obstruction for systems defined on such spaces, we show that a sym-SRE phase cannot appear at certain fillings.

Finally we show there are special cases where obstructions to a sym-SRE insulator occur despite being on symmorphic lattices at even integer filling. These occur only in spin models without charge fluctuations, where reflection symmetry relates two entanglement cuts that can enclose an odd number of sites.

Overview

Before presenting our detailed arguments, we first give an intuitive description of the key ideas and results. A phase is SRE if it can be adiabatically deformed to an unentangled product state (12, 13). Note that there is no assumption of symmetry during the deformation, so topological insulators are SRE. In contrast, gapless phases with algebraic correlations (including both band metals and gapless spin liquids) and gapped phases with emergent anyonic excitations are “long-range entangled” phases.

In this work we prove a general constraint on the number of electrons ν per primitive unit cell required to realize a sym-SRE phase: Consider a system of electrons with Kramers degeneracy. We assume the particle number conservation, a space group symmetry including lattice translations, and TR symmetry. Then, to obtain a sym-SRE phase, ν has to be an even integer. Furthermore, if the space group is NS, ν must be a multiple of 4, 6, 8, or 12, depending on the space group.

We remark that our result is in fact slightly stronger than stated. Under the assumptions of ref. 14, by proving ground state degeneracy on certain geometries we rule out “invertible topological order” (iTO) at these fillings. All SRE phases are (trivial) iTO. In fact, some authors define the term “SRE” to mean iTO. Fortunately our constraint is correct with either definition.

To warm up, we first ignore charge fluctuations and consider an infinite, periodic 1D chain with one localized spin- moment per cell. For an conserving chain at half filling [including SO(3) invariant chains], the HOLSM theorem asserts that the ground state must either be gapless or break a symmetry. A more general version of HOLSM is known in 1D (8): When each unit cell carries a projective representation (or Kramers degeneracy), a sym-SRE phase is forbidden.

To illustrate the ideas discussed in ref. 8, consider a spin- chain with TR symmetry . Suppose the system is in a sym-SRE phase, and consider an entanglement cut at some bond , which determines a Schmidt decomposition of the ground state. Due to the presence of a gap, the high-weight Schmidt states have a discrete spectrum (15), which we label α. The Schmidt states are all either Kramers singlets with or doublets with . This is because in the absence of long-range order, all Schmidt states differ by the action of operators localized near the cut, and local operators never switch the value of . Now advance the entanglement cut by a lattice translation to bond , as illustrated in Fig.1A. On the one hand, we have added one more spin- to the Schmidt states, so their eigenvalue must change by ; on the other hand, the two cuts should be equivalent due to translation invariance, so their eigenvalue should not change. We thus arrive at a contradiction: The Kramers degeneracy carried by each unit cell translates into an obstruction to a sym-SRE phase.

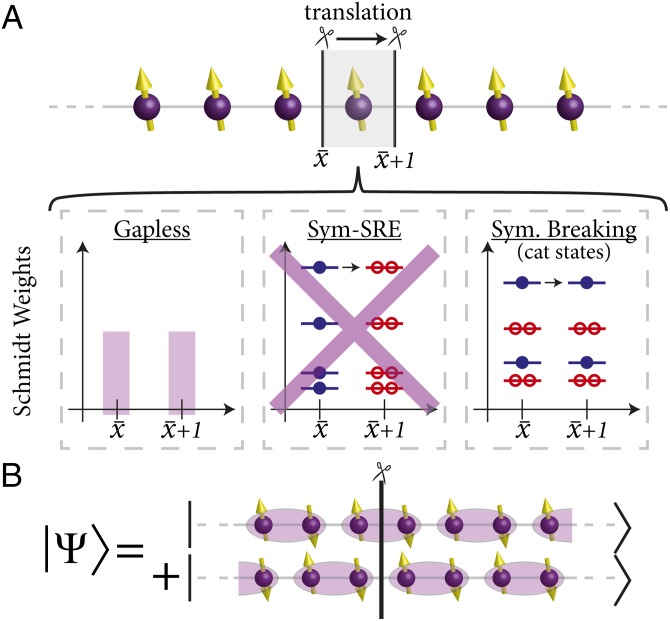

Fig. 1.

Schematic Schmidt decomposition of an infinite periodic chain with one spin- per cell and TR symmetry. (A) Two entanglement cuts, related by a lattice translation, enclose one spin- moment. If the system is in a sym-SRE phase, the Schmidt states have the same eigenvalue at the same cut and have to change from, say, (blue) at cut to (red) at cut , which is inconsistent with translation symmetry. The system can circumvent such obstruction by either becoming gapless or spontaneously breaking symmetry (such that the symmetric state is a cat state). (B) Pictorial description of a VBS cat state.

In 1D there are two ways to circumvent the obstruction. If the system is gapless, the Schmidt weights form a degenerate continuum and it is no longer well defined to track the eigenvalue of any particular Schmidt state. If the system spontaneously breaks a discrete symmetry, one can still form a symmetric combination of the ground states, but it will be a Schrödinger’s cat state with long-range order. For a cat state the Schmidt states look different from each other arbitrarily far away from the cut, and the assignment of eigenvalues may differ across different Schmidt states at the same cut. For example, for the valence-bond solid (VBS) state in Fig.1B, we assign if the entanglement cut dissects a singlet pair and otherwise. Consequently the eigenvalue depends on the Schmidt state and our argument breaks down.

To obtain similar constraints in higher-dimensional periodic systems, one can extend the above argument by suitably imposing periodic boundary conditions with odd circumference in all but one dimension to form a quasi-1D cylindrical geometry and then apply the 1D argument (16). For instance, a TR-symmetric Mott insulator on the Kagome lattice, having three spin- moments per cell, cannot be in the sym-SRE phase. In dimensions higher than 1D, if the system is gapped, the resulting ground state degeneracy at can be either due to spontaneous symmetry breaking or due to topological order. For topological orders with , the topologically degenerate ground states associated with periodic boundary conditions may be related to each other by the symmetries, which is a subtle form of symmetry breaking.

HOLSM is only one example of a much larger class of constraints we obtain using this program: A sym-SRE phase is prohibited whenever two entanglement cuts are related by some spatial symmetry (such as reflection, glide, or screw) and they enclose a projective representation. In particular, a sym-SRE phase can be forbidden even when there are two spin- moments per unit cell when the enclosed volume is only a fraction of the unit cell. Later in this work we demonstrate this by a concrete model of localized spin moments.

In real materials, however, spin- moments typically come from spinful electrons that are not strictly localized. At a formal level, this does not constitute a projective representation in each unit cell and the preceding arguments do not apply. Naively, one might think any constraint on the number of localized spin- moments simply morphs into one on electron filling. Surprisingly, this is not true: There are localized spin models, like the one mentioned above, for which a sym-SRE phase becomes allowed once charge fluctuations are added.

To understand real materials, it is therefore important to extend HOLSM-type theorems to electronic systems with both charge fluctuation and SOC. We address this problem, assuming only particle number conservation and TR symmetry. Our results indicate that an electronic system can be in a sym-SRE phase only when the filling is an even integer. For most NS space groups, the presence of fractional translations in the glides or screws allows us to obtain an even tighter constraint. Two NS space groups, however, are exceptional and do not contain any intrinsically NS elements (17); they instead feature a “Borromean ring” of screws, and our entanglement argument does not distinguish them from the symmorphic ones.

To handle them, we appeal to the following physical intuition: A sym-SRE phase is sensitive only to local physics, so should have a unique ground state on any large lattice geometry that looks locally identical to the translationally invariant infinite Euclidean space. These geometries are the lattice analogs of compact flat manifolds, and by systematically studying all of the compact flat manifolds we obtain the tightest possible lower bounds for a set of “elementary” space groups that we list in Table 1. Using group–subgroup relations, we manage to derive lower bounds on the sym-SRE electron filling for each of all 230 space groups (Fig. S1). These lower bounds are provably tight for all but 10 space groups.

Table 1.

Summary of for elementary space groups

| ITC no. | Key elements | Minimal filling | Manifold name | ||

| AI* | Ent† | Bbb‡ | |||

| 1 | (Translation) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Torus |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | Dicosm | |

| 144/145 | 6 | 6 | 6 | Tricosm | |

| 76/78 | 8 | 8 | 8 | Tetracosm | |

| 77 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 80 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 169/170 | 12 | 12 | 12 | Hexacosm | |

| 171/172 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||

| 173 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 19 | , | 8 | 4 | 8 | Didicosm |

| 24 | , | 4 | 2 | 4 | |

| 7 | Glide | 4 | 4 | 4 | First amphicosm |

| 9 | Glide | 4 | 4 | 4 | Second amphicosm |

| 29 | Glide, | 8 | 4 | 8 | First amphidicosm |

| 33 | Glide, | 8 | 4 | 8 | Second amphidicosm |

The minimal filling required to form a symmetric atomic insulator.

obtained in Extension to 3D Symmorphic and Nonsymmorphic Crystals. Bounds are not tight for nos. 19, 24, 29, and 33.

obtained in Alternative Method: Putting Sym-SRE Insulators on Bieberbach Manifolds. All bounds are tight.

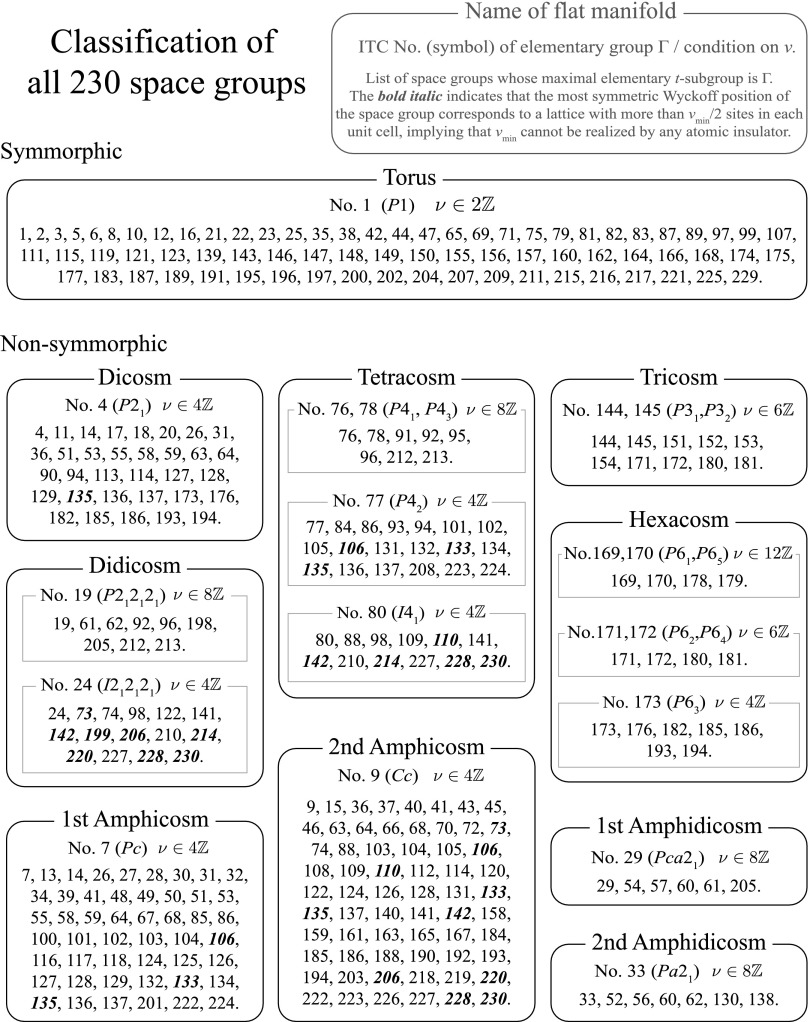

Fig. S1.

Classification of all 230 space groups based on their associated Bieberbach manifolds.

A LSM-Type Theorem for Spin-Orbit Coupled Chains

Here we show that a TR-invariant spin-orbit coupled chain at odd filling cannot realize a sym-SRE phase. The argument presented here paraphrases a more precise proof, using the language of matrix product states in SI Text.

We proceed by assuming the ground state is symmetric, obeys the area law, and is SRE and derive a constraint on the filling ν. Let x label unit cells and be the translation . Each unit cell may contain many sites and orbitals. We Schmidt decompose across a bond , . By the assumption that obeys an area law, the Schmidt spectrum (and hence the label α) is discrete. Each Schmidt state is an eigenstate of the number operator (the total charge to the left), but it is subtle to discuss their eigenvalues as they are ill-defined in the thermodynamic limit. Instead, the well-defined quantity is the charge relative to the mean filling, :

| [1] |

The sum is well conditioned because as exponentially quickly in a sym-SRE state. This follows from the fact that the Schmidt states differ from the ground state only in the vicinity of the cut.

Translation invariance implies that the Schmidt decompositions across different bonds are related by , , with the two translation-related states having the same charge excess . The Schmidt states at the two cuts are related by the addition of the intervening sites, spanned by states :

| [2] |

Choosing a charge eigenbasis for the sites, with , charge conservation implies that whenever we have . However, as long as the state is SRE, , because any two Schmidt states differ by the addition or rearrangement of some particles near the entanglement cut. This is a contradiction unless (the HOLSM theorem). For a cat state of two charge-density wave orders, which is symmetric but not SRE, no longer needs to be an integer and our argument does not apply.

When TR symmetry is incorporated, each Schmidt state is part of either a Kramers singlet or doublet:

| [3] |

Of course is related to , but we have to recall that is defined to be , not . The divergence of the total charge results in an ambiguous but (assuming SRE) α-independent phase, . Again, because of translation invariance, the charge excess and the TR character are independent of .

Now consider the action of on the decomposition (2),

| [4] |

where we used and Eq. 2 again in the last step. Note the factor of compared with . It follows that and hence .

If , one of our assumptions must be violated: Either the phase is gapless, the state breaks a symmetry, or it is symmetric but a long-range correlated cat state. For example, for a gapless system the entanglement Hamiltonian is also gapless: All , the Schmidt states form a continuum, and the symmetry properties of the Schmidt states are ill-defined. Alternatively, for a VBS cat state in Fig. 1B, the ambiguous phase is no longer α independent, but instead will depend on which of the two VBS sectors the Schmidt state belongs to.

Extension to 3D Symmorphic and Nonsymmorphic Crystals

The above argument can be extended to 3D systems, using the quasi-1D (generalized) cylinder . (Our results are also applicable to 2D systems with layer groups, because any layer group has a natural correspondence to a space group.) Given a 3D crystal with the primitive lattice vector , we introduce a periodic boundary condition that identifies with and . We are then left with a single “long” direction with infinite extent along and a translation symmetry . Formally we can view the cylinder as a 1D chain with a 1D-unit cell that comprises of the 3D unit cells. Therefore, choosing to be odd, the constraint on 1D filling implies .

Strictly speaking, at this argument demonstrates there cannot be a symmetric, gapped ground state for an infinite sequence of odd-circumference geometries. Assuming that sym-SRE phases must have a unique (and hence symmetric) gapped ground state on a cylinder of sufficiently large , , we then rule out sym-SRE phases in the thermodynamic limit. Intuitively, a sym-SRE phase cannot detect the global topology (or parity of ) because it is sensitive only to local physics. We comment further on this assumption later. We note that both Oshikawa’s argument (2) and the rigorous results of Hastings on the scaling of the gap (3) also apply only to tori of odd by even circumference. Thus, the same assumption is implicit if their results are taken to rule out sym-SRE phases.

The lower bound is in fact the tightest possible bound for all 73 symmorphic space groups (unless extra constraints, like specifying a lattice realization, are imposed). A space group is symmorphic if every symmetry element can be decomposed into a product of a lattice translation () and a point group element. Such a decomposition implies that putting a site at the “origin” of the point group in each unit cell generates a lattice that respects all of the symmetries. One can then trivially realize an atomic insulator at by putting a Kramers pair of electrons on each site of the lattice. Because we can explicitly construct a sym-SRE state at , the bound is tight.

The situation is very different when the space group is NS, for which given any fixed origin at least one symmetry element contains a fractional translation. As a direct consequence, the unit cell of any lattice compatible with a given NS symmetry must contain more than one site. Because an atomic insulator can be formed by putting a Kramers pair on each site, an upper bound on can be inferred from the lattice with fewest sites. This is listed in the “AI” column of Table 1.

To systematically study all 157 NS space groups, we focus on those 18 space groups listed in Table 1, which we refer to as elementary. All other NS space groups contain at least one of these elementary groups as a subgroup. [More precisely, here we are referring to so-called t subgroups (18), which retain the primitive unit cell of the entire group.] Thus, a lower bound on the elementary space groups immediately provides a lower bound for the others, although further work is required to determine whether the inferred bounds are tight.

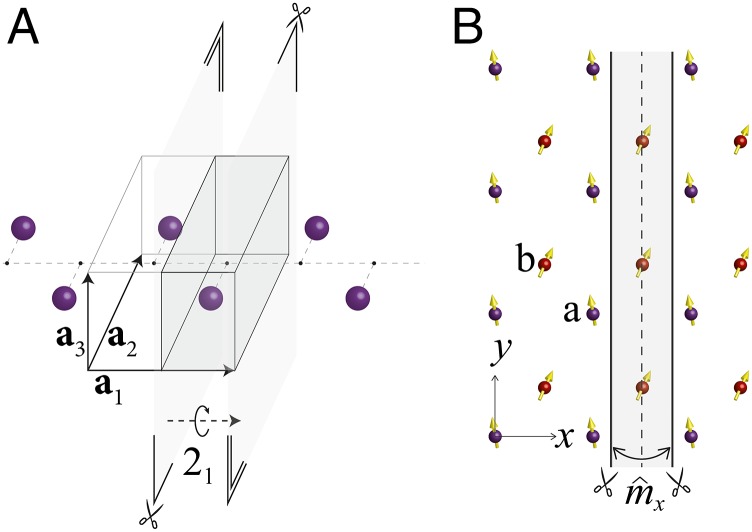

All elementary NS space groups, except for no. 24, are made NS by a screw ( rotation followed by translation) or a glide (a mirror reflection followed by a half translation), which we denote by and list in the “key elements” column of Table 1. To establish a dimensional reduction as before, we have to specify our choice of primitive lattice vectors . We require the following: (i) The NS operation is represented as . Here, is the rotation about an axis parallel to for screws or the mirror about a plane that contains for a glide (where ). (ii) The plane spanned by and is invariant under . For these elementary NS groups, one can check case by case that such a choice is possible. (For nos. 24 and 80 one has to use the conventional cell that contains two primitive unit cells.)

As before, we take a cylinder geometry by introducing the periodic boundary condition for and . We then replace the translation in the above argument with the NS operation . The action of is purely “onsite” in the 1D picture and has no effect on our 1D argument, because merely rotates or reflects the plane spanned by and , as illustrated in Fig. 2A. The volume enclosed by the two cuts related by is times smaller than the symmorphic case, so we now have . Requiring , we prove the listed under column “Ent” in Table 1. (Because the conventional cell of nos. 24 and 80 contains two primitive unit cells, we have to divide the naive bound by 2, leading to the bounds 2 and 4, respectively.) For most of the elementary NS space groups, the lower bound of obtained here coincides with the upper bound from the atomic insulator limit and hence is also the tightest possible bound.

Fig. 2.

Entanglement cuts enclosing fractions of the unit cell. (A) In the quasi-1D setup, two entanglement cuts related by , say a screw, enclose a half-integral volume. (B) Distorted checkerboard lattice. Two entanglement cuts are related by the reflection symmetry.

Alternative Method: Putting Sym-SRE Insulators on Bieberbach Manifolds

The dimensional reduction argument can take advantage only of a single glide or screw symmetry, but no. 24 contains three orthogonal screws, and if any one is absent the crystal is symmorphic. As a result, applying the above argument to any particular screw leads to a nonoptimal bound () for no. 24. Similarly, the bounds obtained for nos. 19, 29, and 33 are not tight because of their multiple NS operations. Therefore, we need new machinery that makes use of multiple NS operations at once. Here we present a different line of argument that overcomes this challenge.

We use the following physical principle: If a Hamiltonian defined on an infinite lattice is in a sym-SRE phase, it will have a unique gapped ground state on any compact lattice geometry in which (i) the Hamiltonian is locally indistinguishable from that on , (ii) the particle density is that of the thermodynamic limit, and (iii) the width of all compact directions is sufficiently larger than some scale comparable to the correlation length. The lattice geometries we have in mind are generalizations of the torus; in the continuum we would say they are “flat.” A discussion and heuristic justification of this principle are included in SI Text.

We first reproduce our constraint on ν for symmorphic crystals. To that end, it is sufficient to put the system on a torus with odd circumferences in every direction, which is a well-defined procedure because the Hamiltonian is translationally invariant. If the filling ν is odd, the total number of electrons is also odd and Kramers degeneracy is unavoidable. However, according to the principle, a sym-SRE phase cannot detect the parity of once and should have a unique ground state. Hence ν must be even.

The advantage of this argument is that one may get a stronger constraint by using manifolds other than the torus. To this end, we discuss how to define a lattice model on a flat manifold obtained by “modding out” by a subgroup of the space group of the Hamiltonian. Let us first formalize the familiar example of putting a translation invariant 1D system onto a ring . If the circumference of the ring is N, we identify sites x with () and operators with . Denoting as the group generated by an N-step translation, one can formally rewrite this identification rule () as

| [5] |

for . Here, is the quantum operator corresponding to g, runs over all of the operators at , and is a unitary matrix representation that could account for any action of g on the internal degrees of freedom, as will eventually be required for SOC. For the usual translation, . The Hamiltonian for the ring is obtained from that of the infinite chain by identifying terms using .

The same procedure applies to more complicated space group symmetries: Given a 3D lattice Hamiltonian symmetric under , we impose the equivalence relation to obtain a lattice model on the space . There are two requirements on to obtain a well-defined lattice Hamiltonian. First, must be fixed-point free (also called “Bieberbach”), as otherwise the manifold will contain conical singularities or edges, so will not be locally indistinguishable from the plane (more details in SI Text). Second, because also encodes the nontrivial action of glides and screws on the internal spin, has to be compatible with certain consistency conditions (namely the existence of the lattice analog of Spin and Pin− structure), which we will return to shortly.

There are 10 compact flat manifolds (known as Bieberbach manifolds) in 3D, and each of them can be obtained by modding out by a Bieberbach group (19). For example, when is generated by a glide and two other orthogonal translations, we obtain a manifold , the so-called “first amphicosm” (19). When is NS, the number of unit cells contained in the resulting manifold can be fractional and will lead to a tighter bound. To derive the constraint for space group no. 24, we use spanned by two screws suitably chosen to avoid a conical singularity (more details in SI Text). The resulting manifold (Fig. S2) contains primitive unit cells of no. 24 and we must have to avoid a Kramers degeneracy. By engineering for each of the elementary space groups, we have obtained the bounds summarized under column “Bbb” in Table 1—sym-SRE phases are allowed when ν is a multiple of . Furthermore, by using group–subgroup relations we determine bounds for each of the 157 NS space groups, which we include in full in SI Text.

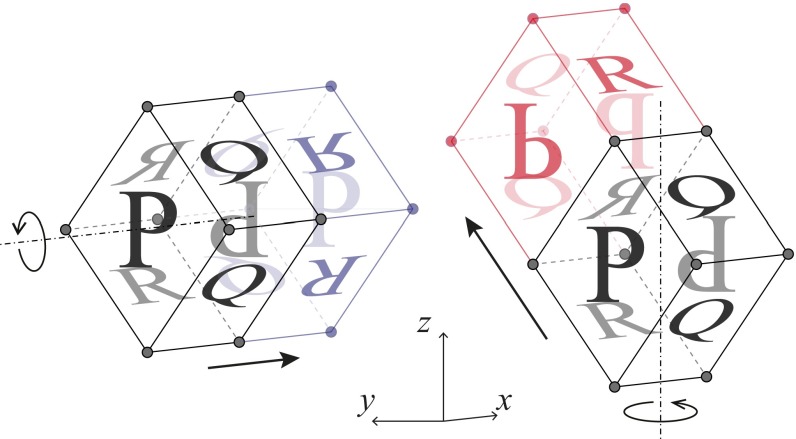

Fig. S2.

Illustration of a didicosm obtained by modding out by a suitably chosen subgroup of space group no. 19. This space group is generated by two orthogonal screws. The black box represents a fundamental domain, and the blue and red boxes are the image of the fundamental domain under the two screws. The letters P, Q, and R and their orientation indicate pairs of faces that are identified.

Are our bounds optimal? Except for 10 NS space groups, we can prove the Bieberbach bound is necessary and sufficient by constructing a noninteracting band insulator at the conjectured filling (20). For 10 NS groups (nos. 73, 106, 110, 133, 135, 142, 206, 220, 228, and 230), however, our method here indicates a sym-SRE insulator is possible at , whereas one can in fact show a band insulator at this filling is impossible. Therefore, there are two possibilities—either one can actually show a stronger interacting constraint that prohibits a sym-SRE phase at (by using purely point group symmetries of the space group, which we did not use in this work) or there indeed exists an interacting example of sym-SRE phase at this filling. The latter option would be quite surprising, implying the gap can be opened at these fillings only with interactions, yet results in a sym-SRE phase—an intrinsically interacting trivial phase.

We note the following technical point. It is well known that consistently defining spinors in the continuum requires the manifold to admit “Spin” or “” structure (21), so we should investigate whether this constraint arises in the SOC lattice setting ( structures extend Spin structures to nonorientable manifolds; the sign indicates that the square of a reflection is ). The subtlety arises because SOC spinful fermion operators transform under a double group of the space group [e.g., SU(2) rather than SO(3) for the proper rotation part of the space group], leading to sign ambiguities in the choice of in Eq. 5. If the signs are not fixed properly, will generate a projective representation of ; i.e., . When is projective, the equivalence relation is ill-defined; we do not know whether we should identify with or . Therefore, we have to carefully choose the sign of each in such a way that forms a linear (nonprojective) representation of . This choice may not be unique, and as detailed in SI Text each choice corresponds to a different Spin/Pin− structure (22). Fortunately, all 3D flat manifolds admit either a Spin or a Pin− structure, so the proper choice of is always possible.

Localized Spin Models: New Symmetry Constraints

So far we have focused on universal constraints on ν with the input of space groups only. We now show that, given specific positions of sites in the unit cell, there is an entirely new class of constraints. Unlike the previous section where we could use only fixed-point free symmetry operations, here we use a point-group symmetry to probe the location of the sites in the unit cell. For this result we must restrict to the strongly Mott-insulating regime where the system reduces to moments at lattice sites. In the presence of certain reflection symmetries, even for symmorphic crystal lattices the minimal filling for a trivial paramagnet can be , not . In particular: If an magnet has an odd number of moments per unit cell lying on a reflection plane, it cannot be in a sym-SRE phase. What was previously the “tightest” bound is increased because here we assume a more constraining scenario; namely we assume specific lattice realizations of the space group where the electrons are strongly localized.

As a concrete example we consider the distorted checkerboard lattice shown in Fig. 2B with moments localized on every lattice site. This is an example of a lattice with the wallpaper group no. 3 (), which contains a mirror . There are two inequivalent mirror planes and , and we consider a lattice formed by putting one site on each of the two planes in each unit cell as shown in Fig. 2B. No symmetry relates the moments on the two sublattices “a” and “b.” Wallpaper group no. 3 is symmorphic and our previous results require only an even filling.

Now let us put the system onto a cylinder with an odd circumference in the y direction. Consider an entanglement cut at anywhere between and x = . Under mirror reflection about the plane , the two entanglement cuts enclose an odd number of sites in sublattice b and hence an odd number of moments. Now suppose that each moment carries a projective representation of some symmetry, say TR or SO(3). Then these symmetry-related entanglement cuts yield corresponding Schmidt states carrying different representations. This rules out a sym-SRE at filling .

Note, however, if charge fluctuations are allowed, then we can localize both electrons to one or the other lattice site and thereby obtain a sym-SRE insulator. Therefore, it was important that we consider the pure spin model. Another route to preserving the obstruction is to consider Hamiltonians with particle-hole symmetry, obtained, for instance, by allowing only hopping between bipartite lattice sites. This also effectively constrains the filling on sites.

Applications

Let us discuss some physical applications of our result. First, a Mott insulator at odd filling either must be gapless or, if gapped, must display a ground state degeneracy. Because we assume only TR but not spin-rotation symmetry, this is of practical relevance in real materials with nonnegligible SOC. Consider the possible ground states for such a Mott insulator in . The conventional insulating ground states, such as charge density or Néel order, have ground state degeneracy resulting from symmetry breaking. However, any other cause for ground state degeneracy, or gaplessness, must have an exotic origin. For example, ground state degeneracy that is not attributable to symmetry breaking implies there is no local operator that could distinguish the different states. This is the hallmark of topological order, as in a quantum spin liquid, where emergent excitations with self or mutual anyonic statistics are expected. Similarly, the conventional origins of gapless excitations in a phase, either a Fermi sea of electrons or Goldstone modes, are both ruled out because we are dealing with a symmetric insulator. The material Herbertsmithite (ZnCu3(OH)6 Cl2) is a Mott insulator with spin moments on a Kagome lattice (23). The ground state is believed to be symmetric because no thermodynamic phase transition occurs on lowering the temperature to a small fraction of the exchange energy. In addition to Heisenberg exchange terms, SOC-induced Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interactions lower the spin rotation symmetry (7) and one cannot directly apply the original HOLSM to this system. However, because TR is preserved, our results imply the resulting ground state must be an unconventional phase of matter such as a gapped quantum spin liquid.

A more surprising application of our results concerns the truly 3D material Na4Ir3O8, in which the iridium atoms form a hyperkagome lattice with 12 sites per primitive unit cell (24). Similar to Herbertsmithite, no thermodynamic phase transition is observed when approaching the zero-temperature limit. In a simplified picture, the system has on average 12 spin-1/2 moments in each unit cell with significant SOC (5), and so neither HOLSM nor our previous argument for Herbertsmithite can rule out a sym-SRE insulating phase. Nonetheless, we can still rule it out by incorporating the NS space group symmetries: Na4 Ir3 O8 crystallizes in the space group no. 213 () (24). Our result allows for sym-SRE only when (Table S1) but for this material.

Table S1.

The filling that may realize sym-SRE phases for nonsymmorphic space groups

| No.* | ν | No. | ν | No. | ν | No. | ν | No. | ν | No. | ν | No. | ν |

| 4 | 39 | 66 | 100 | 129 | 165 | 201 | |||||||

| 7 | 40 | 67 | 101 | 130 | 167 | 203 | |||||||

| 9 | 41 | 68 | 102 | 131 | 169 | 205 | |||||||

| 11 | 43 | 70 | 103 | 132 | 170 | 206 | |||||||

| 13 | 45 | 72 | 104 | 133 | 171 | 208 | |||||||

| 14 | 46 | 73 | 105 | 134 | 172 | 210 | |||||||

| 15 | 48 | 74 | 106 | 135 | 173 | 212 | |||||||

| 17 | 49 | 76 | 108 | 136 | 176 | 213 | |||||||

| 18 | 50 | 77 | 109 | 137 | 178 | 214 | |||||||

| 19 | 51 | 78 | 110 | 138 | 179 | 218 | |||||||

| 20 | 52 | 80 | 112 | 140 | 180 | 219 | |||||||

| 24 | 53 | 84 | 113 | 141 | 181 | 220 | |||||||

| 26 | 54 | 85 | 114 | 142 | 182 | 222 | |||||||

| 27 | 55 | 86 | 116 | 144 | 184 | 223 | |||||||

| 28 | 56 | 88 | 117 | 145 | 185 | 224 | |||||||

| 29 | 57 | 90 | 118 | 151 | 186 | 226 | |||||||

| 30 | 58 | 91 | 120 | 152 | 188 | 227 | |||||||

| 31 | 59 | 92 | 122 | 153 | 190 | 228 | |||||||

| 32 | 60 | 93 | 124 | 154 | 192 | 230 | |||||||

| 33 | 61 | 94 | 125 | 158 | 193 | ||||||||

| 34 | 62 | 95 | 126 | 159 | 194 | ||||||||

| 36 | 63 | 96 | 127 | 161 | 198 | ||||||||

| 37 | 64 | 98 | 128 | 163 | 199 |

Those space groups not listed here are symmorphic and hence ; n in this table is a positive integer .

is prohibited for the noninteracting case. There is no known interacting model of sym-SRE at these fillings either.

is prohibited for the noninteracting case. There is no known interacting model of sym-SRE at this filling either.

One caveat though is that, strictly speaking, the presence of impurities destroys translation invariance, which is crucial to defining filling (23). In addition, for some systems, like Na4Ir3O8, certain atoms are not perfectly ordered and the space group symmetries are only approximate (24).

As a second class of examples consider the Dirac semimetal described in refs. 25 and 26. A simple model of this state is the Fu–Kane–Mele (27) model of electrons on a diamond lattice at half filling , which leads to Dirac cones at face centers of the Brillouin zone. In a noninteracting electron picture, the stability of this interesting electronic structure arises from the NS space group of the diamond lattice, which leads to a four-dimensional irreducible representation. Can strong interactions gap these nodes and lead to a sym-SRE insulator? The diamond lattice is NS and —implying that if the Dirac nodes are gapped, the system necessarily breaks symmetry or is topologically ordered.

We conclude with some open questions. Can one prove that sym-SRE phases have a unique ground state on flat geometries, an assumption also implicit in the common interpretation of Hastings and Oshikawa’s results? For the 10 space groups with a discrepancy between the noninteracting and interacting bounds, is there a tighter interacting bound or an intrinsically interacting sym-SRE phase? Finally, what are the constraints on topological order and symmetry fractionalization for NS lattices, analogous to the analysis for 2D Mott insulators (16)?

SI Text

Proof of Minimal Spin-Orbit Coupled Filling in the Matrix–Product–State Formalism

In the matrix–product–state formalism, a short-range correlated translation invariant wave function is written as

| [S1] |

where the local Hilbert spaces are indexed by and the are “auxiliary” indexes to be summed over. For our purposes, χ can actually be infinite: What is important is that the Schmidt decomposition has a well-behaved and discrete spectrum, which follows from the area law obeyed by gapped ground states (15). An important question is how the global symmetries of manifest themselves in the local tensors B. In our case the global U(1) and time reversal symmetries factorize into their onsite representations,

| [S2] |

| [S3] |

where n label sites and the g are onsite unitary operators. Assuming translation invariance, we drop the superscript n. Standard results (28) show that in the absence of long-range order, is symmetric if and only if

| [S4] |

| [S5] |

for some unitary matrices U, and is the integer filling of the system.

The transformation laws of Eq. S5 define the U only up to a phase. Whereas the onsite symmetries satisfy

| [S6] |

because , the U may realize the symmetry group only projectively,

| [S7] |

In our case this particular relation is not interesting, as we can choose the phase of to set . However, when we compare the equalities contained in Eqs. S5 and S6, we obtain

| [S8] |

which implies

| [S9] |

Unless , we arrive at a contradiction.

On the Physical Principle Used in the Proof

Here we comment on our assumption of the nondegeneracy of a sym-SRE phase on flat, featureless geometries. The assumption was necessary because our results proved degeneracy only on an infinite sequence of geometries, and from this we wish to conclude that the phase cannot be sym-SRE in the thermodynamic limit. The situation is analogous to those of Oshikawa and Hastings, both of which bounded the gap only on odd by even tori. Regardless, their results are commonly interpreted to forbid sym-SRE paramagnets, implicitly invoking this principle. This principle is also implicit in many discussions of classification, so it would be useful to prove, but we do not attempt this here.

We motivate the principle more formally (but no more rigorously) in the case of a torus. An SRE phase is defined by the existence of a path of local Hamiltonians from the Hamiltonian of interest to a sum of single-site operators while preserving the gap (12, 13). The interpolation may break any of the onsite symmetries like time reversal; in fact, for symmetry-protected topological phases it must. However, because there are no examples of symmetry-protected topological phases protected only by translation, and because is translationally invariant, it is reasonable to assume that the sequence of Hamiltonians can be chosen to preserve translation. Using translation invariance, the entire path can be periodized and defined on a large torus, up to some exponentially small ambiguities if the terms in are localized only exponentially. In the trivial limit the torus has a unique gapped ground state because is a sum of single-site terms. Due to the finite gap on the plane, and hence short-range correlations, the periodized should preserve the gap on the torus, in which case the ground state remains unique down to —of course proving this is the main challenge.

There is a more restrictive setting where the argument is precise. Suppose that on the plane can be exactly mapped to the trivial phase via a finite-depth quantum circuit with light cone of radius . We assume further that given some lengths , the gates can be rearranged such that each stage is invariant under the translations . Because the are composed of disjoint gates, for there is an obvious “furled” version defined on a torus of circumference that has the same action as U on all local operators with a size smaller than . Again, can be trivially periodized onto the torus with a unique gapped ground state. Because U takes to on the plane, the finite light cone of also maps to the periodized version of on the torus. So they are isospectral, and is gapped on the torus. More generally, the Bieberbach group will play the role of translation.

One drawback of the Bieberbach method is that it demonstrates exact degeneracy only on odd-volume spaces, whereas Hastings’ result rigorously bounds the scaling of the gap on an even by odd torus.

“Modding Out” and the Emergence of Spin and Pin± from a Lattice Model

Motivation and Setup.

In SI Text, we clarify some subtleties in putting a system on a compact flat manifold . To illustrate the problem, let us first explore a more explicit form of the Hamiltonian on obtained by the modding-out prescription explained in the main text.

To that end, let a subspace be a fundamental domain that contains exactly one of the equivalent points of any . Namely, for any , there exist a unique and such that . Note that g is also unique because is fixed-point free. Although it is not necessary, for simplicity we choose M to be simply connected.

We assume the original Hamiltonian in is a sum of local terms , where has a finite support around . Then consider

| [S10] |

When in this sum is near the boundary of M, might contain operators outside of M; in that case they should be understood as the identified operators inside M, given by the equivalence relation

| [S11] |

Then the natural identification allows us to interpret as the Hamiltonian on . Note that the infinitely many different choices of M give the same as long as one remembers each site in can be labeled by the labels of any of the equivalent sites in .

Whereas the choice of g above, as a space group element, is unique, for SOC fermions the symmetry group has to be extended by the fermion parity and is not uniquely defined. As such, a more careful discussion is warranted and we tackle it in the last subsection of SI Text.

Putting such complications aside, one still sees there are infinitely many valid choices of M. The choice of M, however, is merely a gauge choice. More precisely, in SI Text we show the following: Given any two valid choices of fundamental domains M and , the Hamiltonians and are related by a local unitary transformation.

As an illustrative example, let us consider the following Hamiltonian in 2D,

| [S12] |

where X and Y are spin operators. Note that due to the phase, the lattice translation in x is given by . is invariant under a space group generated by glide ,

| [S13] |

and translation ,

| [S14] |

Let be the subgroup of the full symmetry group generated by and with , being odd integers. As described, we introduce the equivalence relation

| [S15] |

| [S16] |

For example, M can be chosen as . Under identification of the edges of M by , one sees that is actually the Klein bottle.

As described, the modded-out Hamiltonian is then given by

| [S17] |

where we have used Eq. S16 to bring into the region M and as is odd.

Staring at Eq. S17, one sees that

-

i)

Around the “seam” , contains couplings (boundary conditions) that do not seem to coincide with the original Hamiltonian defined on the plane.

-

ii)

The symmetry of is unclear—Does still have something reminiscent of the invariance of ?

For the first point, we argue that the seam of is an artifact of choosing a specific fundamental domain. We can see that the Hamiltonian (deep) inside M (the first sum in Eq. S17) is identical to that of the original Hamiltonian in . By redefining M, any point in can be taken far away from the boundary of M. For example, for (), one may choose

| [S18] |

Therefore, one can argue that any expectation values of local operators or correlation functions around any given points in are unchanged from those in the bulk (for sufficiently large ). This point can be made clearer, using the local unitary equivalence we discuss in the next subsection.

The answer for the second point depends on the property of . To understand this, one should ask, Does always imply for all ? It is easy to see that this is the case only when is a normal subgroup of . When is normal, the invariance of implies the invariance of (up to local unitaries). Even when is not normal, however, is still invariant under the normalizer of in the full symmetry group (e.g., in the above example, the normalizer of in is the subgroup generated by ). For our purpose, the invariance of is not necessary—the properties that each point of is locally identical to the bulk and that remains TR symmetric are sufficient.

Local Unitary Equivalence.

Here we explicitly show the asserted local unitary equivalence among defined with different fundamental domains and discuss its physical consequence.

To this end, we first define a slightly more formal, but nonetheless equivalent, procedure to define the modded-out Hamiltonian in Eq. S10. This merely serves to introduce notations that make the local unitary equivalence manifest. By definition, for any site in there exist and , both unique, such that . In , the action of on any operator is represented by first sending and then conjugating by a local unitary operator . Note that acts nontrivially only on site . After modding out, however, the relabeling becomes trivial because are merely different labels for the same site. The identification of operators, as discussed in Eq. S11, can then be defined via the map .

can be promoted to a linear map acting on any local operators with support in region , provided any two distinct sites in A belong to different equivalence classes. More concretely, we simply have with being a local unitary operator. We can now rewrite the modded-out Hamiltonian in Eq. S10 in a more precise manner:

| [S19] |

In particular, because the elements of commute with time-reversal , is time-reversal symmetric.

Taken at face value, the two Hamiltonians and obtained by modding out with fundamental domains are not identical. However, the choice of the fundamental domain is only a gauge choice and one can always construct a local unitary transform such that . In fact, one simply sees that and therefore . (Note again one can freely switch between the equivalent labels for the same site.)

Such local unitary equivalence implies the ground state expectation value of any local operators with support is identical to that of the bulk with exponential accuracy. If corresponds to a region A deep inside M, this is evident because the ground state is gapped and the restriction of is identical to . If corresponds to a region that crosses the border of M (or equivalently the corresponding region is disconnected in M), one can nonetheless choose a new fundamental domain to center . In essence, given a “measurement region” , one can move any apparent seams arbitrarily far away from it, using (bounded by the size of ), and hence deduce the measurement outcome is identical to the bulk up to exponential corrections. Important to the discussion is that leaves the region unchanged. This should be contrasted with a “visible” defect, say an impurity, which can be moved only by invoking a translation operator and will therefore shift also the measurement region.

Complications with Spinful Fermions: Spin and Pin.

As explained in the main text, the “spin” degrees of freedom complicate the situation because the internal rotations or reflections introduce sign factors that depend on the fermion number . Here we clarify the mathematical structure of Spin or Pin structure on a compact flat manifold in more detail.

Before discussing (s)pin, let us first examine the Bieberbach group itself. The first Bieberbach theorem states that each has a unique decomposition into a product of a (possibly fractional) translation T and an orthogonal transformation , . For our purposes only a discrete subset will appear, such as reflections and rotations. To be fancy, we have the short exact sequence

| [S20] |

where denotes the lattice translations in and r projects onto the point group part of g; i.e., . The map r is the “holonomy representation” of . For the Bieberbach manifold , the fundamental group is ; intuitively this is because a straight line connecting two points on related by becomes a closed curve in . The map r encodes the fact that when traversing a path , we return to the point having been “screwed” by the orthogonal transformation .

In the presence of (s)pin degrees of freedom, G is realized as a extension encoding the sign structure, which we denote by . For instance, for spin-, the rotation is , where denotes the fermion number. The screw and glide transformations then inherit these signs, and a screw will square to a translation and the fermion parity, . Formally,

| [S21] |

where . The most familiar example of this sequence is probably the case of and . The choice of depends on the physical model, but for SOC spin- fermions is a discrete subgroup of the ‘′ group, the unoriented counterpart of . The “” superscript indicates that mirror reflections satisfy , because reflection is implemented on spins as . Generally, we can consider both and , depending on whether reflections square to .

To consistently introduce the equivalence relation on spinful fermions required to mod out by , we need a group homomorphism , which encodes how we choose the sign that can accompany each reflection and rotation. Namely, ε has to satisfy

| [S22] |

such that the following diagram commutes:

| [S23] |

This is a “lift” of the holonomy representation to . Depending on , it may or may not be possible to find such an ε. In fact, ref. 22 shows that Eq. S23 is precisely the condition for the existence of a Spin/Pin structure on . All orientable 3-manifolds admit spin structure and all nonorientable 3-manifolds admit structure. Hence, all 10 Bieberbach 3-manifolds (6 orientable and 4 nonorientable) admit Spin or structure, and such ε always exists.

As an illuminating example, let us discuss the space group no. 29. This group is generated by three symmetry elements

| [S24] |

| [S25] |

| [S26] |

with relations

| [S27] |

where is translation by one unit. Because (I is the inversion) and , we have ε up to signs :

| [S28] |

| [S29] |

| [S30] |

For ε to be homomorphic, ε has to keep relations in Eq. S27. It is easy to see that once we fix , all relations are satisfied without specifying . We thus have structures.

Curiously, this group, no. 29, is the single exception that does not admit structure among all Bieberbach groups. For we have to use so that , which also fixes . Then, the third relation in Eq. S27 is violated. Therefore, we cannot put particles obeying on the manifold “first amphidicosm” obtained by modding out by . This, however, does not concern us here because we are interested in spin-1/2 electrons.

Note that because we consider models with U(1) symmetry, it seems that we could redefine the reflections by an arbitrary U(1) phase θ, . Choosing then erases the distinction between and . Formally this amounts to considering U(1), rather than , extensions of the space group, leading to and structures. However, time reversal narrows down this U(1) ambiguity because the modding-out process must preserve TR symmetry. The space group elements and commute; the lift ε must as well, ; otherwise the seams of the region will break TR. For models, this amounts to requiring

| [S31] |

So TR invariance reduces the U(1) ambiguity back down to , fixing either . For example, for satisfies this, whereas for does not. In general, the relation is invariant under U(1) redefinitions of R (because conjugates phases) and determines which of to use.

Modding-Out Procedure for Space Group No. 24

Here we discuss an explicit example of the modding-out procedure described in the main text and demonstrate how this leads to the filling constraint for any sym-SRE phase in space group no. 24. For brevity, in this section we use the notation to denote the space group indexed by the number n in ref. 18.

To this end, we first focus on , which differs from only in their Bravais lattices: is primitive orthorhombic whereas is body-centered orthorhombic. In particular, we make use of the fact that can be regarded as a subgroup of .

Aside from lattice translations, contains three orthogonal screws of the form

| [S32] |

| [S33] |

| [S34] |

where is the lattice constant along . In the following we always measure “volumes” in units of , the volume of the primitive unit cell of .

Note that , where is the lattice translation along , and , the group identity. is therefore generated by . In particular, observe that are four distinct points not related by lattice translations. Hence, the lattice composing of all of the symmetry-related points of has four sites in each unit cell, and each site “occupies” a volume of .

Suppose we mod out by the entire . As such, the four points and all their lattice translates are identified. The resulting manifold therefore has the same volume as that occupied by in the original lattice; i.e., the resulting manifold (known as the “didicosm”; Fig. S2) has a volume of .

In our argument, however, it is crucial that the resulting manifold is locally indistinguishable from . This implies the following conditions on the subgroup : (i) is fixed-point free, and (ii) has to be arbitrarily large in all linear dimensions. As discussed above, using fails to satisfy condition ii. Intuitively, this can be cured by choosing a “smaller” . More precisely, we demand be chosen such that the images of (say) the origin constitute a superlattice with a unit cell that is arbitrarily large with generic aspect ratios.

This can be accomplished by choosing to be the subgroup generated by , where are integers that can be arbitrarily large. Note that , and . In fact, is identical to but with the rescaled lattice constants . The linear dimensions of are therefore , as desired.

It follows from our previous discussion that the volume of is , an odd-integer multiple of . To avoid Kramers degeneracy the electron filling has to be for any sym-SRE phase symmetric under . Being a subgroup of , is also a subgroup of . Hence the same filling constraint applies to —except that the volume of the primitive unit cell of is twice as big as that of . As a result, the sym-SRE filling constraint is for .

Group–Subgroup Relations and Elementary NS Space Groups

As explained in the main text, all 157 NS space groups contain at least one of the elementary NS space groups as a t subgroup. Fig. S1 illustrates which space group contains which elementary space groups, generated based on ref. 18. Elementary space groups are grouped into 10 Bieberbach manifolds (19).

Using this group–subgroup relation, one can deduce the constraint on filling ν for all nonelementary NS space groups based on the result for NS elementary space groups established in the main text. We list the results in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.Z. is indebted to conversations with M. Cheng, M. Freedman, M. Hastings, M. Hermele, and S. Parameswaran. A.V. thanks S. Parameswaran, A. Turner, and D. Arovas for an earlier collaboration on related topics and L. Balents for insightful discussions and was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant DMR 1206728 and the Templeton Foundation. H.W. thanks T. Morimoto, Y. Fuji, M. Oshikawa, and H. Murayama for useful comments. H.C.P. was supported by a Hellman graduate fellowship and NSF Grant DMR 1206728.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514665112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lieb E, Schultz T, Mattis D. Two soluble models of an antiferromagnetic chain. Ann Phys. 1961;16:407–466. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oshikawa M. Commensurability, excitation gap, and topology in quantum many-particle systems on a periodic lattice. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:1535–1538. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastings MB. Lieb-Schultz-Mattis in higher dimensions. Phys Rev B. 2004;69:104431. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Affleck I. Spin gap and symmetry breaking in layers and other antiferromagnets. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:5186. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balents L. Spin liquids in frustrated magnets. Nature. 2010;464:199–208. doi: 10.1038/nature08917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigol M, Singh RRP. Magnetic susceptibility of the kagome antiferromagnet . Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:207204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.207204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorko A, et al. Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya anisotropy in the spin-1/2 kagome compound . Phys Rev Lett. 2008;101:026405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.026405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Gu ZC, Wen XG. Classification of gapped symmetric phases in one-dimensional spin systems. Phys Rev B. 2011;83:035107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel L, Zak J. Elementary energy bands in crystals are connected. Phys Rep. 2001;341:377–395. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parameswaran S, Turner A, Arovas D, Vishwanath A. Topological order and absence of band insulators at integer filling in non-symmorphic crystals. Nat Phys. 2013;9:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy R. 2012. Space group symmetries and low lying excitations of many-body systems at integer fillings. arXiv:1212.2944.

- 12.Hastings MB, Wen XG. Quasiadiabatic continuation of quantum states: The stability of topological ground-state degeneracy and emergent gauge invariance. Phys Rev B. 2005;72:045141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Gu ZC, Wen XG. Local unitary transformation, long-range quantum entanglement, wave function renormalization, and topological order. Phys Rev B. 2010;82:155138. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong L, Wen XG. 2012. Braided fusion categories, gravitational anomalies, and the mathematical framework for topological orders in any dimensions. arXiv:1405.5858.

- 15.Hastings MB. An area law for one-dimensional quantum systems. J Stat Mech. 2007;2007:P08024. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaletel MP, Vishwanath A. Constraints on topological order in Mott insulators. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:077201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.077201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.König A, Mermin ND. Screw rotations and glide mirrors: Crystallography in Fourier space. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3502–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn T, editor. International Tables for Crystallography. Vol A Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway JH, Rossetti JP. 2003. Describing the platycosms. arXiv:math/0311476.

- 20.Po HC, Watanabe H, Zaletel MP, Vishwanath A. 2015. Filling-enforced quantum band insulators in spin-orbit coupled crystals. arXiv:1506.03816.

- 21.Nakahara M. Geometry, Topology and Physics. 2nd Ed Bristol, UK: IoP Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutowski R, Putrycz B. 2014. Spin structures on flat manifolds. arXiv:1411.7799.

- 23.Helton JS, et al. Spin dynamics of the spin- kagome lattice antiferromagnet . Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:107204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.107204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto Y, Nohara M, Aruga-Katori H, Takagi H. Spin-liquid state in the hyperkagome antiferromagnet . Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99:137207. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.137207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young SM, et al. Dirac semimetal in three dimensions. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108:140405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young SM, Kane CL. 2015. Dirac semimetals in two dimensions. arXiv:1504.07977.

- 27.Fu L, Kane CL, Mele EJ. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:106803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.106803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-García D, Wolf MM, Sanz M, Verstraete F, Cirac JI. String order and symmetries in quantum spin lattices. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:167202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.167202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.