Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (eHCF + LGG; Nutramigen LGG) as a first-line management for cow’s milk allergy compared with eHCF alone, and amino acid formulae in Spain, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health Service (SNS).

Methods

Decision modeling was used to estimate the probability of immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and non–IgE-mediated allergic infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months. The models also estimated the SNS cost (at 2012/2013 prices) of managing infants over 18 months after starting a formula as well as the relative cost-effectiveness of each of the formulae.

Results

The probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months was higher among infants with either IgE-mediated or non–IgE-mediated allergy who were fed eHCF + LGG compared with those fed one of the other formulae. The total health care cost of initially feeding infants with eHCF + LGG was less than that of feeding infants with one of the other formulae. Hence, eHCF + LGG affords the greatest value for money to the SNS for managing both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy.

Conclusion

Using eHCF + LGG instead of eHCF alone or amino acid formulae for first-line management of newly-diagnosed infants with cow’s milk allergy affords a cost-effective use of publicly funded resources because it improves outcome for less cost. A randomized controlled study showing faster tolerance development in children receiving a probiotic-containing formula is required before this conclusion can be confirmed.

Keywords: amino acid formula, cost-effectiveness, cow’s milk allergy, extensively hydrolyzed formula, Spain, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is an immunologically mediated reaction to cow’s milk proteins1 and is one of the most common food allergies in early childhood. It has an estimated incidence ranging between 0.02 and 0.03 in infants.2 Most children will acquire tolerance to cow’s milk proteins within the first 5 years of life,3 although recent evidence suggests that the natural history of this allergy is changing, with an increasing persistence until later ages.4,5 The only proven treatment consists of elimination of cow’s milk proteins from a child’s diet, and for infants, this necessitates that use of standard infant formulae is substituted with a hypoallergenic formula.6

The widely accepted definition of a probiotic is “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”.7 It has been postulated that beneficial probiotics from the human intestinal microflora could restore immune system homeostasis in children with CMA. The probiotic with the greatest number of studies examining possible effects in pediatric allergic disorders is Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG). These studies support the use of LGG in the dietary management of cow’s milk–allergic infants.8 The mechanisms of the beneficial effects are multiple, ranging from modulation of intestinal microflora composition to a direct effect on intestinal mucosa structure and function, and on local and systemic immune response.8

In a recent open, nonrandomized, observational study in Italy, the addition of LGG to an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHCF + LGG; Nutramigen LGG) was found to accelerate the development of tolerance to cow’s milk in infants with CMA compared with those receiving eHCF alone or amino acid formulae (AAF).9 Otherwise healthy cow’s milk–allergic infants (n=260; mean age at recruitment of 5.92 months; 64% male; mean body weight 6.66 kg; 43% with (immunoglobulin E [IgE]-mediated allergy) were prescribed a formula by a family pediatrician or general physician. Infants were excluded from the study if they were fed a preprobiotic product in the previous 4 weeks or if they experienced cow milk protein–induced anaphylaxis, eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, food protein–induced enterocolitic syndrome, or other chronic comorbidities.9 Fifteen to 30 days after starting a formula, the infants were referred to a tertiary pediatric allergy center for a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) to confirm the diagnosis of CMA. The endpoint of the study was the percentage of infants who developed tolerance to cow’s milk at 12 months from the start of a formula. Tolerance was confirmed following the results of a full anamnestic and clinical evaluation, skin prick test, atopy patch test, and oral food challenge. All food challenges were performed in a DBPCFC manner. Clinical acquisition of tolerance was defined by the presence of a negative DBPCFC over a 7-day post-challenge observation period. Infants with negative DBPCFC were re-evaluated after 6 months to check the persistence of tolerance to cow’s milk.9

The study found that significantly more infants in the eHCF + LGG group developed oral tolerance to cow’s milk after 12 months (78.9%; P<0.05) compared with those fed with eHCF alone (43.6%) or an AAF (18.2%).9

Data from this study (provided by the study’s authors) were used to construct two decision models to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of using eHCF + LGG as a first-line formula for managing IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated allergic infants in Italy.10

The comparative health economic impact of eHCF + LGG, eHCF, and AAF in Spain is unknown, and therefore, dietetic choices are based largely on their safety, nutritional value, and purchase cost. Hence, the objective of the current study was to amend the Italian decision models10 to estimate the cost-effectiveness of using eHCF + LGG as a first-line formula for CMA compared with eHCF and AAF in Spain, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health Service (SNS).

Methods

Economic model

The Italian decision models depicting the management of IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated cow’s milk–allergic infants were adapted to reflect the structure of the Spanish health care system and the context in which CMA is managed in this country. Similarly, patients’ pathways and resource use were adapted using estimates derived from the pediatric authors. The period of the models was up to 18 months or when an infant developed tolerance to cow’s milk if that occurred earlier.

Model inputs – clinical outcomes

The models were populated with data from an observational study (as previously described).9,10 The percentages of infants who developed oral tolerance to cow’s milk after being fed a formula were used to populate the models with the probability of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk at different time points, as previously described for our Italian models.10

Model inputs – resource use

The models were populated with estimates of health care resource use pertaining to the management of infants with CMA in Spain. These estimates were based on the clinical experiences of the pediatric authors.

The general pediatricians who participated in this study each see a mean of <50 infants with suspected CMA per annum, with a mean age at presentation of ~4 months (range 3–6 months). According to these pediatricians, all infants with IgE-mediated allergy and 80% of those with non–IgE-mediated allergy are expected to be referred to a pediatric specialist (ie, gastroenterologist or allergist) for further investigations and confirmation of diagnosis. The time from referral to seeing a pediatric specialist would be 2–4 weeks. The pediatric specialists who participated in this study each see a mean of 130 infants with CMA per annum, with a mean age at presentation of ~5 months (range: 2–9 months).

One-third of infants would generally be prescribed a formula at the initial visit to a pediatrician and the remainder at the second or third visit. In addition, 80% of infants would be prescribed an emollient for 6–12 months, 35% would be prescribed a corticosteroid for 7–10 days, and 70% an antihistamine for 7–10 days.

The SNS reimburses the cost of prescriptions for nutritional formulae and ~50% of the cost of prescribed medicines for cow’s milk–allergic infants. Hence, parents do not incur prescription costs for nutritional formulae or co-payments for clinician visits and diagnostic tests.

Pediatricians prescribe formula based on an infant’s age and weight. Hence, up to 3 months of age, it would be ~150 mL/kg/day (500–1,000 mL/day) decreasing to ~120 mL/kg/day (800–900 mL/day) at 6 months of age. Between 7 and 9 months of age, infants would receive ~600 mL/day decreasing to ~400 mL/day at >1 year of age. Infants enter the model at a mean age of <6 months. Hence, it was estimated that infants would be prescribed 48×400 g cans of formula in the first 6 months of the models, 36×400 g cans of formula in the next 6 months of the models, and 36×400 g cans of formula after 12 months.

Statistical analyses

Using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), differences in tolerance acquisition between formulae were adjusted for any differences in the following baseline variables: age, sex, presenting symptoms, and baseline values of the diagnostic tests. Covariates that had a P-value ≥0.05 were excluded from the ANCOVA model. For the IgE model, the only covariate that remained was prick test result at baseline (P=0.006). For the non-IgE model, the only covariates that remained were respiratory symptoms (P=0.03) and atopy test results at baseline (P=0.01). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Model outputs

The primary measure of clinical effectiveness was the probability of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months.

Unit costs at 2012/2013 prices (Table 1)11 were assigned to the estimates of resource use in the models in order to calculate the cost of health care resource use funded by the SNS over 18 months from the start of a formula.

Table 1.

Unit costs in Euros at 2012/2013 prices

| Resource use | Unit cost (€) |

|---|---|

| Visits | |

| Initial pediatrician visit | 62.24 |

| Follow-up pediatrician visit | 43.37 |

| Initial pediatric specialist visit | 133.68 |

| Follow-up pediatric specialist visit | 71.30 |

| Tests | |

| Skin prick test | 95.08 |

| Radioallergosorbent test (RAST) | 29.86 |

| Atopy test | 18.55 |

| Food challenge | 95.08 |

| Special formulae | |

| eHCF (per 400 g can) | 25.90 |

| eHCF + LGG (per 400 g can) | 27.50 |

| AAF (per 400 g can) | 39.90 |

| Prescribed medication | |

| Emollients (per month) | 24.13 |

| Corticosteroids (for 7 days) | 4.29 |

| Antihistamines (for 7 days) | 3.72 |

Note: Data from Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. https://www.msssi.gob.es.11

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.

The models were used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of using one formula compared with another in terms of the incremental cost per additional infant who developed tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months in Spain. This was calculated as the difference between the expected costs of two dietetic strategies divided by the difference between the expected outcomes of the two strategies in terms of the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk. If one of the formulae improved the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk for less cost, it was considered to be the dominant (cost-effective) dietetic strategy.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess uncertainty within the models, probabilistic sensitivity analyses were undertaken (10,000 iterations of each model) by simultaneously varying the probabilities, clinical outcomes, resource use values, and unit costs within the model. A beta distribution was used to represent uncertainty in probability values by assuming a 5% standard deviation around the mean values. Clinical outcomes and resource use estimates were varied randomly according to a log-normal distribution by assuming a 10% standard deviation around the mean values. Unit costs were varied randomly according to a gamma distribution by assuming a 10% standard deviation around the mean values. The outputs from these analyses were used to estimate the probability of being cost-effective at different thresholds of incremental cost per additional infant who developed tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months.

In addition, deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed to identify how the incremental cost-effectiveness of one dietetic strategy over the other would change by varying different parameters in the model. The budget impact and resource implications of starting infants with eHCF + LGG compared with current practice were also estimated for the annual cohort of newly-diagnosed infants with CMA in Spain.

Results

Probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk

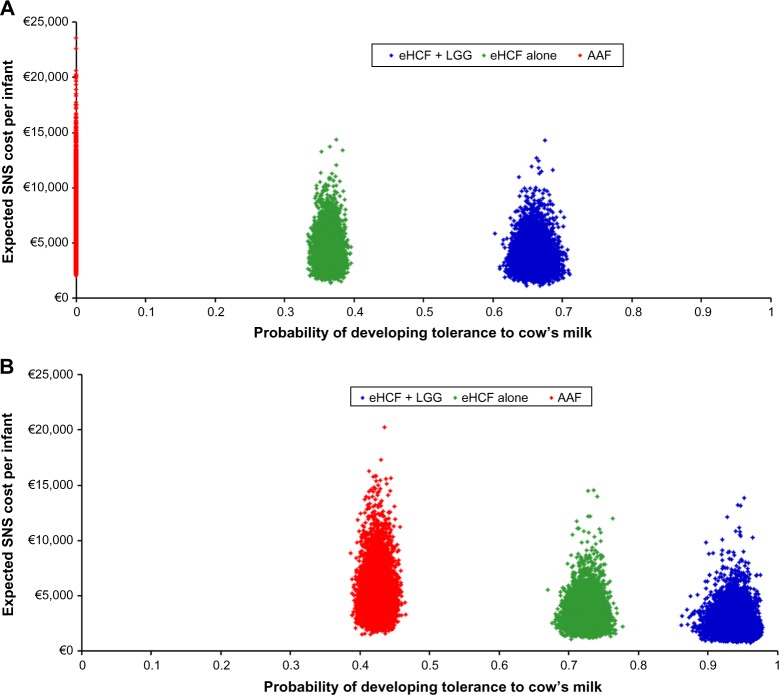

The probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk was higher among infants who were initially fed with eHCF + LGG (Figure 1). Also, the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk was higher among those infants with non–IgE-mediated CMA compared to those with IgE-mediated allergy.

Figure 1.

Expected probability of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months after starting a formula.

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.

Health care resource use and corresponding costs

An infant who is initially managed with eHCF + LGG is expected to consume fewer health care resources than infants managed with the other formulae (Table 2). Hence, initially feeding infants with eHCF + LGG instead of the other formulae is expected to free-up health care resources for alternative use by other patients. Consequently, the total health care cost of initially feeding infants with eHCF + LGG was estimated to be less than that of feeding infants with one of the other formulae (Table 2).

Table 2.

Expected levels of health care resource use and corresponding costs in Euros at 2012/2013 prices over 18 months from starting a formula

| eHCF + LGG

|

eHCF

|

AAF

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-mediated | Non–IgE-mediated | IgE-mediated | Non–IgE-mediated | IgE-mediated | Non–IgE-mediated | |

| Mean resource use per patient | ||||||

| Number of visits to a pediatrician | 10.42 | 9.17 | 12.23 | 10.59 | 13.59 | 11.73 |

| Number of visits to a pediatric specialist | 4.61 | 3.79 | 5.32 | 4.63 | 5.83 | 5.31 |

| Number of skin prick tests | 2.40 | 1.71 | 3.00 | 2.40 | 3.44 | 2.95 |

| Number of RAST | 2.20 | 1.57 | 2.74 | 2.20 | 3.15 | 2.70 |

| Number of atopy tests | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Number of oral food challenges | 2.05 | 1.46 | 2.56 | 2.05 | 2.94 | 2.52 |

| Mean cost of health service resource use per patient (€) | ||||||

| Pediatrician visits | 471.12 | 416.95 | 549.47 | 478.61 | 608.84 | 528.18 |

| Pediatric specialist visits | 391.16 | 332.82 | 441.71 | 392.59 | 478.34 | 441.03 |

| Tests | 493.47 | 353.17 | 614.60 | 493.53 | 705.23 | 605.22 |

| Prescribed drugs | 81.36 | 69.89 | 91.39 | 82.31 | 98.08 | 92.83 |

| Prescribed formula | 2,382.71 | 1,800.83 | 2,714.76 | 2,273.91 | 4,727.07 | 4,143.48 |

| Total | 3,819.82 | 2,973.66 | 4,411.93 | 3,720.95 | 6,617.56 | 5,810.74 |

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

Of the three formulae, use of eHCF + LGG resulted in a lower 18 months cost and a greater probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk than the other two formulae among infants with both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated CMA (Table 3). Hence, starting feeding with this formula was found to be the dominant strategy (Table 3). Also, initial feeding with eHCF was found to be a dominant strategy when compared to starting feeding with an AAF for both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated infants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness of eHCF + LGG versus eHCF and eHCF versus AAF

| Expected SNS cost per patient over 18 months | Expected probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months | Expected SNS cost-difference | Expected difference in probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk | Incremental cost for each additional infant acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-mediated infants | |||||

| eHCF + LGG | €3,820 | 0.55 | −€592 | 0.29 | Dominant |

| eHCF | €4,412 | 0.26 | −€2,206 | 0.26 | Dominant |

| AAF | €6,618 | 0.00 | |||

| Non–IgE-mediated infants | |||||

| eHCF + LGG | €2,974 | 0.91 | −€747 | 0.29 | Dominant |

| eHCF | €3,721 | 0.62 | −€2,090 | 0.32 | Dominant |

| AAF | €5,811 | 0.30 | |||

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; SNS, Spanish National Health Service.

Sensitivity analyses

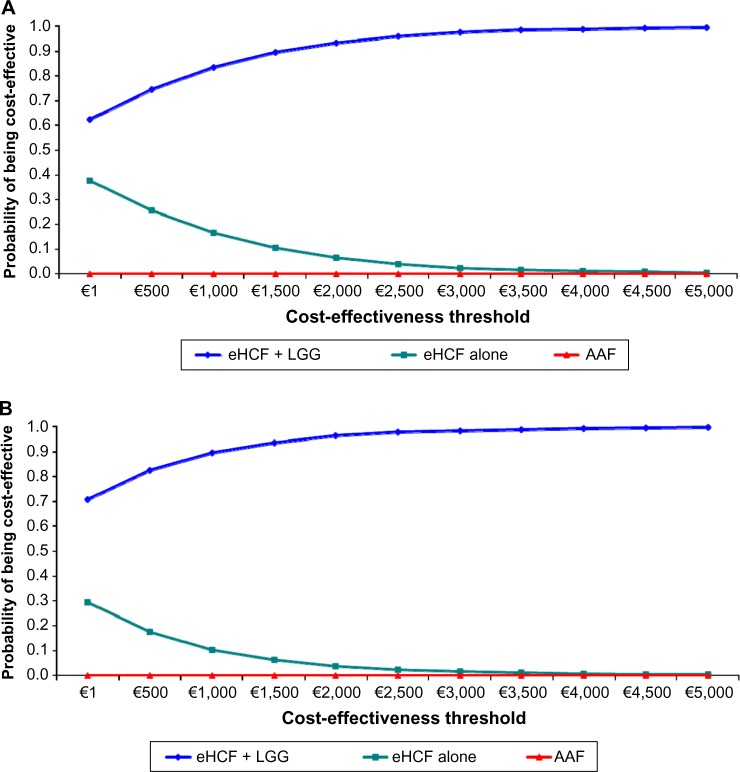

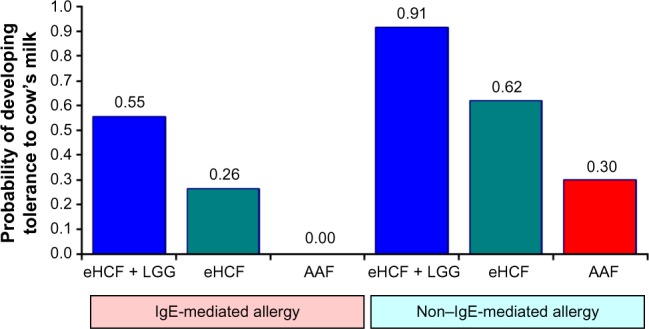

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed to estimate the distribution of expected SNS costs (Figure 2) over 18 months from starting a formula and probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months. Using these distributions, the probability of each formula being cost-effective at different cost-effectiveness thresholds was estimated (Figure 3). These graphs show that the probability of eHCF + LGG being cost-effective was greater than that with the other formulae for both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated allergic infants, from the perspective of the SNS. Moreover, these graphs suggest that neither eHCF nor AAF would afford a cost-effective use of resources when compared with eHCF + LGG.

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of expected SNS costs over 18 months from starting a formula and expected probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months among IgE-mediated allergic infants, generated by 10,000 iterations of the model. (B) Distribution of expected SNS costs over 18 months from starting a formula and expected probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months among non–IgE-mediated allergic infants, generated by 10,000 iterations of the model.

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; SNS, Spanish National Health Service.

Figure 3.

(A) Probability of being cost-effective at different cost-effectiveness thresholds for IgE-mediated allergic infants, from the perspective of the SNS. (B) Probability of being cost-effective at different cost-effectiveness thresholds for non–IgE-mediated allergic infants, from the perspective of the SNS.

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; SNS, Spanish National Health Service.

These analyses also indicate that eHCF + LGG affords the greatest value for money to the SNS followed by eHCF and AAF, in that order, for managing infants with both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated allergy. Hence, eHCF + LGG is ranked as the preferred formula, and AAF the last formula of choice.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses (Table 4) demonstrated that inclusion/exclusion of the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk after 12 months has minimal impact on the results. Additionally, changes in resource use can potentially change costs incurred by the SNS, but they are unlikely to change the ranking of dietetic choices. The relative cost-effectiveness of the three formulae was not sensitive to changes in any other model input.

Table 4.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses

| Scenario | Formula | Range in expected probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk

|

Range in expected SNS cost per patient

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-mediated | Non–IgE-mediated | IgE-mediated | Non–IgE-mediated | ||

| Assume no more infants develop tolerance to cow’s milk after 12 months | eHCF + LGG | 0.55–0.50 | 0.90–0.85 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline |

| eHCF | 0.25–0.20 | 0.60–0.55 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | |

| AAF | 0.00–0.00 | 0.30–0.25 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | |

| Assume no incremental improvement after 6 months and no more infants develop tolerance to cow’s milk after 12 months | eHCF + LGG | 0.55–0.45 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline |

| eHCF | 0.25–0.15 | 0.60–0.50 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | |

| AAF | 0.00–0.00 | 0.30–0.20 | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | |

| The number of follow-up visits to a pediatrician ranges from 50% below to 50% above the base case value | eHCF + LGG | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €3,600–4,000 | €2,700–3,200 |

| eHCF | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €4,100–4,700 | €3,500–4,000 | |

| AAF | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €6,300–6,900 | €5,500–6,100 | |

| The number of follow-up visits to a pediatric specialist ranges from 50% below to 50% above the base case value | eHCF + LGG | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €3,600–4,000 | €2,800–3,100 |

| eHCF | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €4,200–4,600 | €3,600–3,900 | |

| AAF | Unchanged from | Unchanged from baseline | €6,400–6,800 | €5,600–6,000 | |

| The number of diagnostic tests ranges from 50% below to 50% above the base case value | eHCF + LGG | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €3,600–4,000 | €2,800–3,100 |

| eHCF | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €4,200–4,700 | €3,500–3,900 | |

| AAF | Unchanged from baseline | Unchanged from baseline | €6,300–6,900 | €5,500–6,000 | |

Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formulae; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG; SNS, Spanish National Health Service.

Budget impact and resource implications of using eHCF + LGG

There are an estimated 0.43 million live births in Spain per annum,12 and the incidence of CMA is reported to be 0.025.2 Hence, there are an estimated 10,750 new CMA-affected infants per annum in Spain. Using the distribution of formula use estimated from the pediatric authors, current management of all 10,750 newly-diagnosed infants was estimated to result in 60% of the cohort developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months, 118,300 visits to general pediatricians, 51,400 visits to pediatric specialists, 78,200 diagnostic tests, and a cost to the SNS of €43.8 million. If all these infants were initially managed with eHCF + LGG, it is expected that 78% of the cohort would develop tolerance to cow’s milk by 18 months, and there would be 12,200 fewer visits to general pediatricians, 5,900 fewer visits to pediatric specialists, 13,700 fewer diagnostic tests and a cost reduction to the SNS of €6.3 million.

Discussion

This study would appear to be the first analysis to assess the cost-effectiveness of using alternative dietetic formulae for managing cow’s milk–allergic infants in Spain. The basis of the analysis was the only comparative analysis of eHCF + LGG with eHCF and AAF currently available.9 The advantage of using this observational data set is that the dietary effect was measured under controlled conditions. However, infants were not randomized to their formula, sample sizes were small in absolute terms and unbalanced between the groups, and resource use was not recorded.9 The study’s authors made every attempt to account for baseline differences between the groups and to overcome the nonrandomized study design.9 Additionally, in this study, differences in developing tolerance to cow’s milk between treatments were adjusted for any heterogeneity in baseline variables using ANCOVA. Nevertheless, there may have been some differences that have not been accounted for. The inherent variability and uncertainty of using data from this small and unequal sample of patients were addressed to some extent by our extensive sensitivity analyses. The results from the observational study9 are consistent with another study which showed that in both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated CMA, the addition of LGG to eHCF resulted in a higher rate of developing tolerance after 12 months of feeding.13

The relative cost-effectiveness of eHCF + LGG in Spain is consistent with the findings from our recent study in Italy which also found that initial use of eHCF + LGG as a first-line management for CMA was cost-effective when compared with eHCF alone, soy-based formulae, hydrolyzed rice formulae and AAF.10 Additionally, our real-world evidence study in the United States found that more cow’s milk–allergic infants, who were initially managed with eHCF + LGG in clinical practice, were successfully managed compared with those who were fed with eHCF alone or AAF.14 The US analysis also found that initial dietary management with eHCF + LGG instead of eHCF alone or AAF affords a more cost-effective use of health care resources because it reduced costs and released health care resources for alternative use within the system without impacting on the time needed to manage the allergy.14 There were no other published studies assessing the health economic impact of alternative formula for the management of CMA, except our previous UK study,15 which also used real-world evidence and found that eHCF alone affords a cost-effective use of health care resources in clinical practice when compared with AAF.

The decision models used for this analysis are based on observational data. Hence, the models may not necessarily reflect clinical outcomes associated with managing a large cohort of infants in clinical practice. Accordingly, the results should be viewed with some caution until more data become available, which can be used to update the models, particularly the findings from a randomized, controlled study measuring the cost-effectiveness of tolerance development in children receiving a probiotic-containing formula compared with other formulae.

The study has several other limitations. The models were informed with assumptions about treatment patterns from the pediatric authors, who are based at one of seven centers. Hence, the levels of health care resource use incorporated into the models may not be representative of the whole of Spain. There was insufficient published clinical evidence to enable us to extrapolate the models beyond 18 months. Therefore, the analysis estimated the cost-effectiveness of managing infants up to 18 months and does not consider the potential impact of managing infants who remain allergic beyond that period. Infants in the observational study9 were well matched, but those with comorbidities were excluded. Hence, the decision models used resource estimates for the “average infant” and do not consider the impact of other factors that may affect the results, such as co-morbidities, underlying disease severity, and pathology of the underlying disease. Additionally, the analysis does not consider the suitability of infants to receive different formulae. The models only analyzed direct health care costs borne by the SNS and excluded any costs incurred by parents and indirect costs incurred by society as a result of employed parents taking time off work. Also excluded are changes in quality of life and improvements in general well-being of sufferers and their parents as well as parents’ preferences. Consequently, this study may have underestimated the relative cost-effectiveness of eHCF + LGG.

Despite these limitations, the models show that over the first 18 months, proportionally more infants fed with eHCF + LGG are likely to develop tolerance to cow’s milk than those fed with the other formulae. Consequently, they cost the health service less to manage. This is an expected finding because infants who develop tolerance to cow’s milk would no longer require any management or feeding with a hypoallergenic formula. Accordingly, treating the annual cohort of 10,750 new CMA-affected infants in Spain with eHCF + LGG instead of the current mix of formulae could increase the percentage of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk from 60% to 78% and free-up 18,000 visits to pediatricians and reduce health service costs by up to €6.3 million. Clearly, initial use of eHCF + LGG has the potential to release health care resources for alternative use within the system.

Conclusion

In conclusion, within the study’s limitations, first-line management of newly-diagnosed infants with CMA with eHCF + LGG instead of eHCF or an AAF improves outcome, releases health care resources for alternative use, reduces costs to the SNS, and thereby affords a cost-effective use of publicly funded resources. Hence, eHCF + LGG is the preferred first-line formula for newly-diagnosed infants compared with the other dietetic choices. A randomized controlled study showing faster tolerance development in children receiving a probiotic-containing formula is required before this conclusion can be confirmed.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was supported with an unrestricted research grant from Mead Johnson Nutrition (Spain) S.L., Madrid, Spain. However, Mead Johnson Nutrition had no influence on 1) the study design; 2) the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; 3) the writing of the manuscript; and 4) the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Mead Johnson Nutrition. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Allen KJ, Koplin JJ. The epidemiology of IgE-mediated food allergy and anaphylaxis. Immun Allergy Clin North Am. 2012;32:35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apps JR, Beattie RM. Cow’s milk allergy in children. Cont Med Educ. 2009;339:b2275. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Høst A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, Christensen AE, Herskind AM, Plesner K. Clinical course of cow’s milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immun. 2002;13:23–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.13.s.15.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE- mediated cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2007;120:1172–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy Y, Segal N, Garty B, Danon YL. Lessons from the clinical course of IgE-mediated cow milk allergy in Israel. Pediatr Allergy Immun. 2007;18:589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kneepkens CM, Meijer Y. Clinical practice. Diagnosis and treatment of cow’s milk allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:891–896. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(8):506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berni Canani R, Di Costanzo M, Pezzella V, et al. The potential therapeutic efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in children with food allergies. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:655–664. doi: 10.3390/ph5060655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Formula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: a prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guest JF, Panca M, Ovcinnikova O, Nocerino R. Relative cost-effectiveness of an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;2015:145–152. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S80130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Available from: https://www.msssi.gob.es.

- 12.Statistical National Institute . Evolucion De Los Nacimientos en Espana De 2008 a 2013 [Evolution of births in Spain from 2008 to 2013] Washington, DC: Statistical National Institute (fuente INE); 2014. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus GG on tolerance acquisition in infants with cow’s milk allergy: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:580–582. 582.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ovcinnikova O, Panca M, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared to an extensively hydrolyzed formula alone or an amino acid formula as first-line dietary management for cow’s milk allergy in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:145–152. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S75071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor RR, Sladkevicius E, Panca M, Lack G, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed formula compared to an amino acid formula as first-line treatment for cow milk allergy in the UK. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(3):240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]