Abstract

The chemopreventive actions of vitamin D were examined in the N-nitroso-tris-chloroethylurea (NTCU) mouse model, a progressive model of lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). SWR/J mice were fed a deficient diet (D) containing no vitamin D3, a sufficient diet (S) containing 2000 IU/kg vitamin D3, or the same diets in combination with the active metabolite of vitamin D, calcitriol (C) (80 μg/kg, weekly). The percentage (%) of the mucosal surface of large airways occupied by dysplastic lesions was determined in mice after treatment with a total dose of 15 or 25 μmol NTCU (N). After treatment with 15 μmol NTCU, the % of the surface of large airways containing high-grade dysplastic (HGD) lesions were vitamin D-deficient +NTCU (DN), 22.7 % (p<0.05 compared to vitamin D-sufficient +NTCU (SN)); DN + C, 12.3%; SN, 8.7%; and SN + C, 6.6%. The extent of HGD increased with NTCU dose in the DN group. Proliferation, assessed by Ki-67 labeling, increased upon NTCU treatment. The highest Ki-67 labeling index was seen in the DN group. As compared to SN mice, DN mice exhibited a 3-fold increase (p <0.005) in circulating white blood cells (WBC), a 20% (p <0.05) increase in IL-6 levels, and a 4 -fold (p <0.005) increase in WBC in bronchial lavages. Thus, vitamin D repletion reduces the progression of premalignant lesions, proliferation, and inflammation, and may thereby suppress development of lung SCC. Further investigations of the chemopreventive effects of vitamin D in lung SCC are warranted.

Keywords: Chemoprevention; dysplasia; lung squamous cell carcinoma; NTCU mouse model; vitamin D; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer kills more than 160,000 individuals in the United States annually. Reduction of lung cancer mortality may be achieved by identification and treatment of higher risk individuals with effective cancer preventive agents. Candidate chemopreventive agents should have favorable activity and safety in pre-clinical models that mirror human disease (1). Clinical chemoprevention studies in lung cancer often examine the effects of agents on premalignant squamous lesions in patients at risk; such lesions can be regularly monitored by bronchoscopy (1).

In SWR/J mice, N-nitroso-tris-chloroethylurea (NTCU) induces premalignant lesions that progress to frank lung SCC. This process resembles the stepwise progression observed during the development of lung SCC in humans (2). Thus the NTCU model provides a unique pre-clinical tool in which to explore the molecular events involved in the progression of premalignant lesions to lung SCC. Others have demonstrated that the development of lung SCC tumors can be reduced in the NCTU model by treatment with Chinese herbs, pomegranate, pioglitazone, or ginseng (3-6). However, there have been no studies focused on the effect of chemopreventive agents on the development of premalignant lesions.

One agent of interest for the chemoprevention of lung cancer is vitamin D. Vitamin D regulates a number of biological processes that are disrupted during cancer development including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, immune suppression/ inflammation and angiogenesis (7, 8). Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), synthesized in the skin following UVB exposure or ingested in the diet, undergoes two sequential hydroxylation reactions to produce 1,25D3 (calcitriol). 25D3 (calcifediol), the product of the first hydroxylation reaction, is the primary circulating metabolite and used as a measure of vitamin D body stores. Defining vitamin D sufficiency/ deficiency remains controversial. The Institute of Medicine concludes that 25D3 levels of 20 ng/mL are required for good bone health, and that there are no convincing data that higher blood levels are associated with improved health outcomes (9). In contrast, numerous epidemiologic studies indicate that 25D3 levels ≥ 32 ng/mL are associated with a reduced incidence of stroke, cardiac disease, autoimmune diseases and many types of cancer (10-12). Relevant to our study are reports that low serum levels of 25D3 are associated with increased risk and poor prognoses of lung cancer (13, 14).

The anti-cancer effects of vitamin D are attributed to differential gene regulation, mediated by binding of the most active metabolite of vitamin D, (1,25D3), to the vitamin D receptor (VDR). Ligand-activated VDR binds vitamin D response elements (VDRE) within gene promoter regions (7). Supporting an anti-tumor role for vitamin D signaling in lung cancer are findings by us and others that VDR expression is associated with improved survival in non- small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and 1,25D3 significantly inhibits growth of VDR-expressing NSCLC cell lines (15-17). VDR is expressed within premalignant lesions of the central airway (18). Therefore, it is plausible that VDR signaling may be activated within premalignant lesions by dietary vitamin D or calcitriol to prevent their progression.

Beyond its effects on the bronchial epithelium, vitamin D may also modify lung carcinogenesis by modulating the immune system (19, 20). Calcitriol is locally produced from circulating 25D3 in immune cells within the lung resulting in monocyte activation and the suppression of lymphocyte proliferation, cytokine synthesis and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling through indirect and direct VDR:VDRE gene regulation (21-24). The success of immune targeted therapies has renewed interest in the role of the immune system in development of lung cancer. However, little attention has focused on the relationship between vitamin D and immune regulation in lung cancer. It has been shown that vitamin D enhances the antimicrobial response to the respiratory pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (22). Additionally vitamin D deficiency (0 IU/kg) promotes pulmonary inflammation in response to ovalbumin in mice (25). These studies indicate the need for further investigation into the relationship of vitamin D, inflammation, and lung cancer.

To determine the potential of vitamin D to prevent progression of SCC, we examined the effects of dietary vitamin D3 intake and systemic calcitriol administration on dysplasia, nuclear localization of VDR, proliferation and inflammation in mice treated with NTCU. Our data show that the development of high-grade dysplasia is significantly reduced in vitamin D sufficient mice, compared to mice that are vitamin D deficient. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the impact of vitamin D on the development of premalignant lesions of the lung.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Reagents

Calcitriol (1,25D3) (PCCA) was prepared in 100% ethanol at a concentration of 2.4 mM (1mg/ml), stored at −80°C, and further diluted in sterile saline weekly for treatment. NTCU (Toronto Research Co.) was aliquoted into 10-20 mg amounts, purged with argon to reduce oxidation, and stored at −20°C. NTCU was diluted in acetone weekly for treatment.

NTCU Mouse Studies

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with IACUC approved protocols in a pathogen free AAALAC certified facility. SWR/J mice (Jackson labs) were selected based on susceptibility and tolerance to NTCU (2). The sub-scapular region of the mice was shaved prior to the first NTCU treatment (2). Aliquots of NTCU (25 μl of 40 mM NTCU = 0.28 mg NTCU = 1 μmol) or vehicle (acetone) were applied to the shaved area once weekly for the intervention studies (40 mM: 1×/wk of 40 mM) or twice weekly for the acute studies (at 3.5 day intervals) (80 mM: 2×/wk of 40 mM), throughout the duration of each experiment. For the intervention study, 12-week old female mice (n=180) were randomized into 2 groups to receive diets that were identical, with the exception of vitamin D3 content (0 IU/kg or2000 IU/kg vitamin D3) (Harlan Tekland). Female mice were chosen as all published studies demonstrate the efficacy of NTCU in female mice (2, 26). One thousand IU/kg is the amount of D3 recommended for mouse diets (27). Diet modification was initiated at 12 weeks of age. Five weeks later, when vitamin D deficiency was established, mice on each diet were further randomized into 3 groups (15 mice/group/time point (15 & 25 wks)) to receive control (acetone), NTCU or NTCU with calcitriol. The calcitriol groups received 26.7 μg/kg Monday, Wednesday and Friday (total weekly dose = 80 μg/kg) by intraperitoneal (IP) injection and +NTCU groups received equal volumes of IP saline on the same schedule.

Mice were weighed biweekly. Toxicity from the carcinogen was manifested as weight loss, superficial skin lesions, and lethargy. If weight loss was greater than 10%, treatment was interrupted and mice were allowed to recover, Missed treatments were added to the end of the study in order to maintain a total delivered dose of 15 μmol or 25 μmol NTCU. Mice were euthanized and lung lobes were either inflated with 10 % neutral buffered formalin (VWR) and paraffin embedded or flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for isolation of RNA.

Blood Collections for Analysis of Metabolites & White Blood Cell Counts

Retro-Orbital Bleeds & Cardiac Punctures

Serial blood samples were collected by retro-orbital bleeding. Approximately 100-150 μl of whole blood per mouse per bleed was collected. Larger volumes of blood were collected by cardiac puncture upon study termination.

White Blood Cell Isolation & Enumeration

Whole blood was collected into EDTA and diluted in RBC lysis buffer. Following wash with PBS, cells were pelleted. Recovered white blood cells (WBC) were re-suspended in 200 μl of 0.6 mM EDTA phosphate buffered saline (E-PBS). 100 μl of the WBC suspension was cytospun and stained with Diff Quick (Dade Behring). The number of lymphocytes and neutrophils in approximately 500 cells/treatment group were determined. The remaining WBC suspension was further diluted in 400 μl of E-PBS and counted using a Beckman Coulter Vi-Cell cell counter to determine the cell number/total volume of blood collected.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

E-PBS (1 mL) was instilled into the trachea and then aspirated. The solution was re-instilled 8 times. The volume of lavage solution that was recovered was noted, and the lavage dispensed into a second tube for cell enumeration. Once the cells were counted, the volume recovered from the instillation was used to calculate total cell number.

Vitamin D Metabolites & Calcium

25D3 and 1,25D3 were measured in sera pooled for each group at multiple time points. 25D3 levels were measured using liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry at the University of Pittsburgh or Heartland Assays (Ames). 1,25D3 levels were also measured by Heartland Assays using a radio-immunoassay. Serum calcium was measured with a colorimetric assay (Point Scientific). Serum PTH plasma levels were measured using the Mouse PTH 1-84 Elisa Kit (Immutopics).

Luminex – Multiplex Assay

The RPCI Flow and Image Cytometry Facility performed the analysis of cytokines in mouse plasma using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Th-17 Magnetic Bead Panel- Immunology Multiplex Assay (EMD Millipore). Pooled samples from each group (acetone control, 80 mM/wk NTCU or 40 mM/wk NTCU after 1, 2, 15 and 25 wks of NTCU treatment) were analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry

For histologic assessment of lesions, formalin fixed lung tissue was paraffin embedded and cut into 5 micron thick sections. Three sections at least 100 microns apart were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and scored to allow for adequate sampling of the lung. H&E staining was conducted using a standard protocol (28). Standard immunohistochemistry techniques were employed to stain for Ki-67, cytokeratin 5 & 6 (CK 5/6), thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1), p63, and F4/80 (26). The IHC technique used for VDR is similar to the IHC method cited above except that slides were processed with an ABC kit (Vector Labs) to enhance the visualization of VDR (18). Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: (VDR, 1:250 MA1-710 (Affinity Bio); p63, 1:1500 SC-8431 (Santa Cruz); TTF-1, 1:400 M3675 (Dako); and F4/80, 1:100 AB6640 (Abcam). See supplemental Figure 1 for immunohistochemistry controls.

Scoring Histopathology & Staining

Lung histology was assessed in an un-blinded fashion by two observers. There was ≥90 % concordance between observers for all lesions. Histological classifications of NTCU induced premalignant lesions, discussed in detail in Hudish et al. (26), were used as a reference. Lung histology was assessed in the large airway (trachea and left and right main stem bronchi) in 3 H&E sections per mouse. Ten to 15 mice per treatment group were scored. The mucosal surfaces of large airways occupied by normal epithelium, atypia, low-grade dysplasia (LGD)(inclusive of squamous metaplasia and mild dysplasia) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD)(moderate and severe dysplasia) were determined. Subsequently the % of surface area of the large airway occupied by each lesion was enumerated in increments of 25% per section. For example, the area in one cross-section of a large airway may contain 50% low-grade dysplasia, 25% atypia, and 25% normal tissue, thus taking into account the variation in histological subtypes within a single airway. Then, the mean % of airway occupied by each lesion was calculated per mouse. Finally, data were averaged for all mice within a treatment group to determine the mean % of airway occupied by each lesion type per treatment group. This is the first study to quantify the lesions in the larger airways apart from the small airways. Small airways were scored per bronchial opening based on the predominant lesion present because little variation was seen within most small airways.

VDR staining was assessed using a published method (18). VDR staining was scored by counting the number of positively stained cells in a section of large airway. Five hundred cells were counted, and the percentage of positive cells was characterized as follows: absent, <10% positive, 10-50% positive, or >50% positive (1 section per mouse and 5 mice per treatment group were analyzed). Ki-67 staining was scored by a standard technique (29). The number of positively stained nuclei in 500 cells in sections of large airway was determined (1 section per mouse and 5 mice per treatment group).

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated and purified from lung tissue using the Trizol method and standard techniques (30). Total RNA (500 ng/sample) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using random hexamers and the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). Quantitative PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems Taqman Gene Expression Array reagents and the ABI Prism 7300 Real Time PCR System by standard techniques. Primer probe sets IL-6 (Mm00446190_m1) and GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1) were used. GAPDH served as the internal control. The relative changes in gene expression were calculated using the comparative CT method (31).

Statistics

The frequency and the percentage of lesions were compared between groups using the Kruskal-Wallis Anova test. When appropriate, Dunn’s test was used to conduct post-hoc pairwise comparisons. VDR quantitation was compared using the Fisher’s exact test, while the Ki-67 quantitation was compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum exact test. All other comparisons were made using the student’s t-test. A significance level of 0.05 was considered for all analyses.

RESULTS

Effects of Dietary Vitamin D3 and Calcitriol (1,25D3) on Serum Vitamin D Metabolites and Calcium in the NTCU Mouse Model

Pilot NTCU dosing studies reveled that cutaneous applications of 25 μl of 40 mM NTCU (N) once weekly were well tolerated, permitting long-term studies. To examine the effects of vitamin D on progression of squamous cell carcinoma, mice were randomized into 2 groups to receive diets containing either 0 (deficient: D) or 2000 IU/kg (Sufficient: S) vitamin D3. Mice on each diet were further subdivided into 3 groups (15 mice/group/time point (15 & 25 wks)) and treated with acetone control (D or S), NTCU only (DN or SN) or NTCU + calcitriol (DN+C or SN+C) (Fig. 1A). All groups that received a vitamin D deficient diet had mean serum 25D3 levels <4 ng/ml (p<0.0001). Among groups on a vitamin D supplemented diet but not receiving calcitriol, the mean 25D3 serum level was 19 ng/ml. In the SN + C group, the mean serum 25D3 level was 10ng/ml (p<0.005) (Table 1). Serum 1,25D3 levels, measured between 8 and 30 wks after the start of diet were decreased in mice receiving the deficient diet (DN) compared to the supplemented diet (SN), as expected (32). To assess the effect of calcitriol on 1,25D3 levels, blood was obtained 1 h post calcitriol treatment. Regardless of diet, 1,25D3 levels of nearly 300 pg/mL were achieved (Table 1). Serum calcium remained within normal ranges in all groups (Table 1)(32). Parathyroid hormone (PTH) was suppressed in the calcitriol treated groups (data not shown). Mice in all groups treated with NTCU gained or maintained weight within 10% of initial body weight throughout the experiments (Table 1). However, as noted in Tables 2 and 3 the number of surviving mice out of the initial 15 mice/treatment arm in the 25 μmol NTCU group on the vitamin D deficient diet (DN) was reduced by 47% compared to the NTCU group on the sufficient diet (SN).

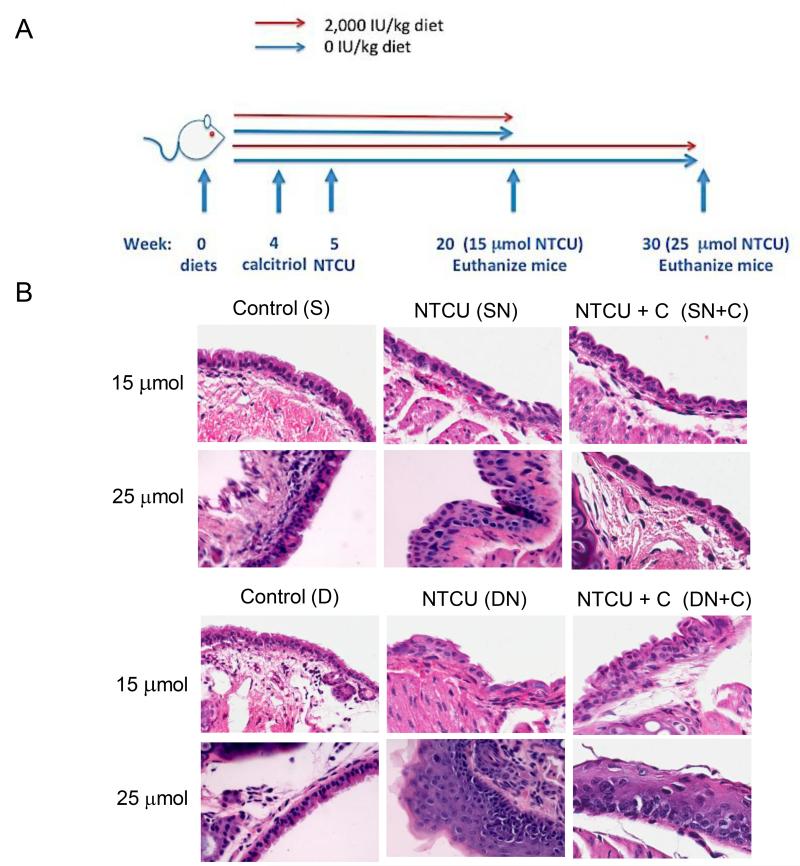

Figure 1. Disease progression in the large airways with 15 μmol & 25 μmol NTCU respectively.

A. Treatment scheme of the vitamin D intervention study in the NTCU model. B. Representative H&E staining of the premalignant lesions induced by NTCU in the large airways after 15 μmol & 25 μmol of NTCU: Examples are shown of normal airway epithelium in the S and D groups, the LGD induced by 15 μmol NTCU in the SN, SN+C, and DN +C groups, and HGD that develops in the DN group. LGD remained the most frequent lesion present after treatment with 25 μmol of NTCU in the SN, SN+C and DN +C groups (represented here), whereas mice in the DN group had a greater percentage of surface area of airway occupied by HGD lesion (represented here). (Magnification: 400×)

Table 1. Body Weight & Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3, 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Calcium.

| Groups | Dietary vitamin D3 (IU/kg) |

Body weight (g) | Serum 25D3 (ng/ml) |

Serum 1,25D3 (pg/ml) |

Serum calcium (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone (S) | 2000 | 22.8 ± 0.9 | 20 ± 1.1 | 88 ± 18.3 | 9.90 ± 0.05 |

| NTCU (SN) | 2000 | 18.1 ± 0.4* | 19 ± 0.5 | 88 ± 17.8 | 9.90 ± 0.27 |

| NTCU ± calcitriol (SN+C) | 2000 | 18.5 ± 0.4 | 10 ± 1.1** | 290 ± 12.7+ *** | 9.97 ± 0.32 |

| Acetone (D) | 0 | 22.7 ± 0.9 | < 4 ± 0.2*** | 43 ± 1.6 | 10.30 ± 0.20 |

| NTCU (DN) | 0 | 19.4 ± 0.6 | < 4 ± 0*** | 40 ± 0.6 | 10.23 ± 0.27 |

| NTCU ± calcitriol (DN+C) |

0 | 19.0 ± 0.4* | < 4 ± 0*** | 288 ± 26.5+ *** | 9.40 ± 0.80 |

Body weight is the mean +/− SEM of the final weight of mice within a given group after 25 weeks of NTCU or control.

Serum 25D3 and calcium values are the mean +/− SEM collected throughout the course of the experiment (4- 30 weeks).

Serum 1,25D3 values are the mean +/− SEM collected at 8, 24 & 30 weeks.

Reflects serum collected ~1 hour post calcitriol (1,25D3) treatments.

(p<0.05),

(p<0.005)

( p<0.0001) compared to Acetone (S)

Table 2. Frequency of Normal histology, Atypia, Low-grade Dysplasia & High-grade Dysplasia in the Large Airways After NTCU Treatment.

(N mice with at least 1 lesion / N total mice in group (% of total))

| Treatment group | Normal | Atypia | Low-grade Dysplasia |

High-grade Dysplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 weeks of NTCU (15 μmol) | ||||

| S | 11/11 (100) | |||

| SN | 12/14 (86) | 14/14 (100) | 6/14 (43) | |

| SN+C | 13/14 (93) | 13/14 (93) | 7/14 (50) | |

| D | 15/15 (100) | |||

| DN | 4/10 (40) | 10/10 (100) | 9/10 (90) | 10/10 (100) |

| DN+C | 2/12 (17) | 10/12 (83) | 12/12 (100) | 7/12 (58) |

| 25 weeks of NTCU (25 μmol) | ||||

| S | 14/14 (100) | 1/14 (7) | ||

| SN | 5/13 (38) | 13/13 (100) | 13/13 (100) | 9/13 (69) |

| SN+C | 2/8 (25) | 8/8 (100) | 8/8 (100) | 4/8 (50) |

| D | 10/10 (100) | 2/10 (20) | ||

| DN | 2/7 (29) | 5/7 (71) | 5/7 (71) | 7/7 (100) |

| DN+C | 3/10 (30) | 10/10 (100) | 10/10 (100) |

Table 3. Percentage of the Surface Area of the Large Airways with Normal Histology, Atypia, Low-grade Dysplasia & High-grade Dysplasia After NTCU Treatment.

| Treatment group |

N | Normal | Atypia | Low-grade Dysplasia |

High-grade Dysplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 weeks of NTCU (15 μmol) | |||||

| S | 11 | 100 ± 0 | |||

| SN | 14 | 26 ± 17.9 | 63.5 ± 17.5 | 8.72 ± 9.5 | |

| SN+C | 14 | 38.5 ± 27.1 | 53.3 ± 23.3 | 6.6 ± 7.7 | |

| D | 15 | 100 ± 0 | |||

| DN | 10 | 3.8 ± 6.7 | 25.3 ± 10.5 | 48.3 ± 9.2 | 22.7 ± 8.8†‡ |

| DN+C | 12 | 0.8 ± 1.8 | 23.2 ± 21.3 | 63.1 ± 20.4 | 12.3 ± 13.9 |

| 25 weeks of NTCU (25 μmol) | |||||

| S | 14 | 99.7 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 1.1 | ||

| SN | 13 | 4.9 ± 8.0 | 38.2 ± 16.2 | 48.5 ± 14.1 | 8.4 ± 7.7 |

| SN+C | 8 | 6.4 ± 15 | 41.4 ± 28.7 | 40.4 ± 29.1 | 11.8 ± 15.6 |

| D | 10 | 97.9 ± 5.3 | 2.1 ± 15.3 | ||

| DN | 7 | 3.5 ± 6.6 | 12.5 ± 35.6 | 48.5 ± 27.4 | 35.5 ± 21†‡ |

| DN+C | 10 | 5.42 ± 9.2 | 72.9 ± 14.9 | 21.3 ± 10.3 | |

Percent of lesions are represented as the mean of total airways scored per group +/− SEM; 3 sections (each ~ 100 microns apart) were scored per mouse

significant p<0.05 compared to S

significant p<0.05 compared to SN

The Frequency and Percentage of Airway Occupied by High Grade Dysplasia is Reduced in Vitamin D3-Sufficient Mice

The development of lung SCC is a multi-step process. It is unclear the mechanism(s) whereby NTCU induces SCC of the lung. NTCU did not induce the development of lesions or tumors other than those reported. However, <5% of all mice spontaneously developed lung adenoma/adenocarcinomas, as has been well described in the SWR/J mouse (33). One mouse in the DN group developed a lymphoma. To assess chemopreventive actions of vitamin D, the lesions in the large airways were quantified. Similar numbers of large airways were scored in all groups. Changes in the frequency and percentage of airway occupied by HGD were used as endpoints to compare groups.

All NTCU-treated groups had significantly more lesions after treatment with 15 μmol of NTCU than corresponding acetone controls, in which there was no evidence of bronchial epithelial changes. The development of lesions in NTCU-treated mice was marked by the loss of cilia and columnar morphology and increased chromatin material, characteristic of squamous metaplasia and dysplastic lesions (Fig. 1B). Dietary vitamin D3 supplementation resulted in ~50% reduction in the frequency of HGD after 15 μmol of NTCU: SN (43%) and SN+C (50%), compared to the DN group (100%)(p<0.05)(Table 2). Treatment with calcitriol had no significant impact on HGD occurrence in vitamin D sufficient group. As illustrated in Figure 1B, the predominate lesions in the SN, SN+C, and DN+C groups were LGD. The DN group developed more HGD, which is distinguished from LGD by the increased variation in nuclei shape in more than half to all of the thickness of the lesion. Calcitriol was also protective, as 58 % of mice in the DN+C group developed HGD after 15 μmol of NTCU, compared to 100% in the DN group (p<0.05)(Table 2). However, HGD frequency in the SN +C group remained at the same level as was seen after 15 μmol of NTCU (50%)(Table 2).

In addition to reducing the frequency with which HGD occurred, the percentage of airway occupied by HGD lesions after treatment with 15 μmol of NTCU was significantly less in the SN (8.7%), SN+C (6.6%) and reduced in the DN+C (12.3%) groups compared to the DN (22.7%)(p<0.05) group (Table 3). It was also noted that the percentage of LGD in mice that received 15 μmol NTCU was on average higher in the SN group than the DN group. The relative increase in LGD and decrease in HGD in SN mice compared to DN mice indicates that vitamin D repletion prevents the progression of LGD to HGD. As compared to the 15 μmol NTCU treatment, the percentage of HGD lesions after treatment with 25 μmol of NTCU increased in both the deficient groups, DN (35.5%) and DN+C (21.3 %). The percentage of HGD in the sufficient groups remained less than the deficient groups. Moreover, little dose-dependent increase was observed in the percentage HGD lesions in the SN (8.4)(p<0.05) and SN+C (11.8) groups (Table 3). The prominent lesion in the small airways of NTCU-treated mice was atypia, regardless of vitamin D status or NTCU dose (Supplemental Table 1).

To confirm that the lesions that developed were squamous in nature, immunohistochemistry markers that are used to identify human lung SCC (CK 5/6 and p63) and adenocarcinoma (TTF-1) were examined. The lesions that developed in the large airway of NTCU mice had increased expression of CK5/6 and p63, whereas the expression of TTF-1 decreased (Fig. 2A, 2B & 2C). The expression of CK 5/6 and p63 were greater in the DN group compared to the SN group after treatment with 25 μmol of NTCU, consistent with our observation that deficient mice have more advanced squamous lesions (Fig. 2B & 2C).

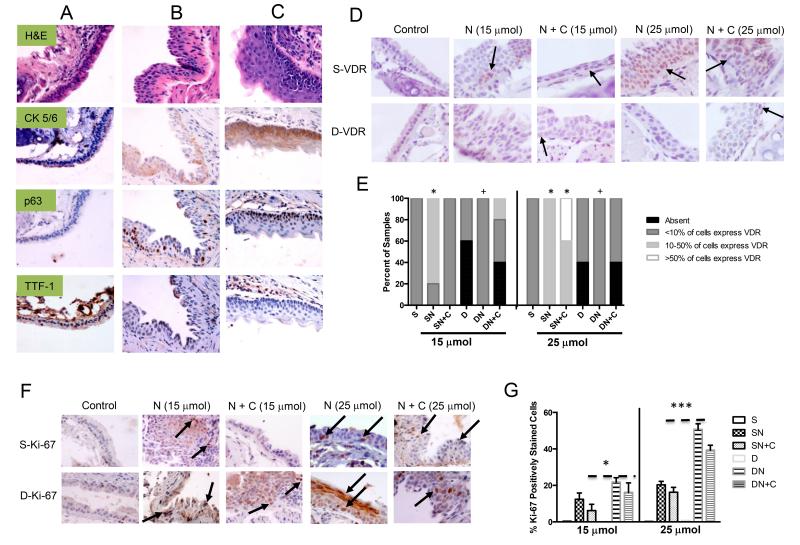

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical detection of lung SCC markers, VDR and Ki-67 in lung tissue from mice treated with 15 μmol or 25 μmol of NTCU.

Compared to A. vitamin D sufficient mice (S), there was increased expression of CK 5/6 and p63 and loss of TTF-1 with the development of premalignant lesions induced by 25 μmol of NTCU in B. vitamin D sufficient mice (SN) and C. vitamin D deficient mice (DN). D. and E. The number of airway epithelial cells positively stained for VDR increased with NTCU treatment in vitamin D sufficient mice (SN & SN+C) compared to deficient mice (DN). F and G. The number of epithelial cells positively stained for KI-67 was significantly higher in mice treated with NTCU particularly in the deficient mice (DN &DN+C). [*(p<0.05) & ***(p<0.0005) compared to S and +(p<0.05) compared to SN] (Magnification: 400× (except VDR: 600×)) Arrows indicate positively stained cells.

Vitamin D Receptor Expression Increases in a Lesion and Ligand Dependent Manner

Vitamin D metabolites bind to VDR to elicit anti-cancer activity. We therefore examined the effect of carcinogen treatment and dietary intervention on VDR levels. Comparing the S to SN or D to DN groups, we find that VDR is up regulated by carcinogen exposure. This agrees with human data, where nuclear VDR increases with disease progression (18). However, our data indicate that disease progression is not the sole determinant of VDR expression. If we compare SN to DN after 15 μmol of NTCU, we see that VDR is higher in the SN group (p<0.05)(Fig. 2D & 2E). This occurs despite the fact that lesions are more advanced in the DN group. No differences in VDR mRNA expression were detected in lung tissues regardless of disease or vitamin D status (data not shown). The most likely explanation for the elevation in VDR expression in SN mice compared to DN mice is that ligand upregulates/stabilizes VDR protein (34, 35). These data suggest that vitamin D repletion is needed to maintain VDR expression and presumably function in premalignant lesions.

Proliferation Is Reduced in NTCU-Induced Bronchial Lesions in Vitamin D3-Sufficient Mice

Numerous studies have demonstrated that calcitriol and its analogues inhibit cell proliferation through VDR-dependent transcriptional processes (36). To examine the effects of vitamin D status on proliferation within lesions we used immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67, which is classically used to measure proliferation in the development of bronchial dysplasia. There was an increase in Ki-67 staining in all of the NTCU treated groups after 15 μmol of NTCU treatment compared to S (p<0.01). There was more Ki-67 staining in the DN group compared to SN (p<0.05). Calcitriol-treated groups (SN & DN) had approximately a 5% reduction in Ki-67 in comparison to their respective NTCU treated groups (Fig. 2F & 2G). Following 25 μmol of NTCU treatment, the percentage of positively stained cells increased approximately 2-fold in all treatment groups. However, staining in the DN group was 30% higher than the SN group (p<0.001). The addition of calcitriol continued to reduced proliferation in the DN+C (12% decrease)(p<0.01) and the SN+C groups (6% decrease)(Fig. 2G). These data suggest that vitamin D sufficiency reduces proliferation, and that calcitriol partially overcomes the enhanced proliferation observed in vitamin D deficient mice.

NTCU-Induced Inflammation Is Reduced in Vitamin D3-Sufficient Mice

Inflammation is associated with the development of squamous cell carcinoma (37), and vitamin D has the potential to modify inflammation (23). Therefore, we examined the local and systemic effects of NTCU administration on inflammation in vitamin D sufficient and deficient mice. This was done by measuring IL-6 plasma levels systemically and local pulmonary IL-6 mRNA expression. Additionally, we examined the early inflammatory events induced by NTCU treatment in vitamin D deficient and sufficient mice by studying mice after two weeks of treatment with NTCU.

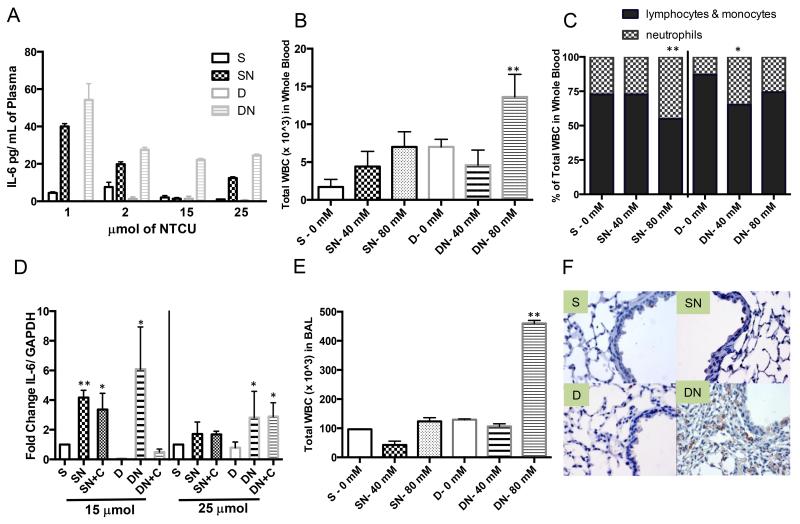

Systemic Inflammation

NTCU increases plasma IL-6 levels in DN mice compared to SN at each time point investigated (p<0.05) (Fig. 3A). These data suggest that NTCU elicits an enhanced inflammatory state in the DN mice. Consistent with this idea, two weeks following NTCU treatment, the WBC count in the DN-80 mM group was markedly increased compared to all other groups (p<0.05). There was a dose dependent increase in the number of WBCs in the SN group (Fig. 3B). Differential staining indicated that the increase in WBCs consisted predominately of neutrophils in the SN-80 mM group (p<0.01) and the DN-40 mM and DN-80 mM groups (p<0.05). Little change was seen in the SN-40 mM group compared to S alone (Fig. 3B & 3C). The large increase in the number of WBCs in the DN-80 mM group consisted of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes.

Figure 3. Immune modulation in response to vitamin D in the NTCU model.

A. Plasma IL-6 levels are elevated in the DN group throughout the vitamin D intervention study (S: SN or S: DN, p<0.05 and SN: DN p<0.05). B. The total of WBCs collected in whole blood after acute NTCU treatment are significantly greater in the DN group (2 wks of NTCU: 40 mM (2 μmol) & 80 mM (4 μmol)). C. The percentage of neutrophils in WBCs increased after acute NTCU treatment. D. IL-6 expression was increased in the lungs of DN mice following NTCU treatment. E. Total WBC counted in BALs are significantly greater in the DN group after 2 wks of acute NTCU treatment, and F. F4/80 staining of mouse macrophages increased in the small airways after 25 μmol of NTCU in the DN group. (Magnification 400×) [*(p<0.05) & **(p<0.005) compared to S.]

Local Inflammation

The expression of IL-6 in lung tissue was increased after 15 μmol of NTCU compared to control (S) in the SN (p<0.01), SN+C (p<0.05) and DN (p<0.05) groups. In the DN mice there was an average 6-fold increase in expression. The magnitude of NTCU induction of IL-6 was reduced in the 25 μmol NTCU groups. The DN and DN+C groups had higher expression than SN or SN+C groups, further suggesting persistent inflammation in vitamin D deficient mice (p<0.05)(Fig. 3D). Additionally, BALs were collected following 2 weeks of treatment with 40 or 80 mM NTCU. The number of macrophages in the BALs of mice treated with 80 mM NTCU was increased compared to control (p<0.05). The acute, pro-inflammatory effect of NTCU was enhanced in the deficient mice (p<0.01)(Fig. 3E). To evaluate local inflammation in the vitamin D deficient NTCU-treated mice at later time points, lung tissue from S, SN, D & DN after 25 wks of treatment was stained with F4/80, a mouse macrophages marker. F4/80 was most readily detected in the DN group (Fig. 3F). Cumulatively, these data suggest an association between increased inflammation and vitamin D deficiency, which correlates with enhanced disease progression.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiologic studies suggest vitamin D may play a role in cancer prevention; numerous studies describe the inverse associations between 25D3 levels or UVB exposure and cancer risk. Mohr and colleagues determined that lower levels of UVB exposure are independently associated with higher lung cancer incidence (38). Pre-clinical studies suggest that the active metabolite of vitamin D, 1,25D3, contributes to the prevention of adenocarcinoma of the lung (39). Lung cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases, and the activity of vitamin D metabolites may differ among histotypes. Our studies focused on the role vitamin D in preventing the progression of premalignant squamous lesions. We discovered that the incidence and progression of premalignant lesions is decreased in vitamin D sufficient mice as compared to vitamin D deficient mice. Our data further suggest that vitamin D deficiency increases inflammation (both locally and systemically) and proliferation of pre-malignant cells thereby enhancing progression of squamous lesions.

Using an approach analogous to that employed in recent human trials of chemopreventive agents (iloprost & myoinositol) in bronchial carcinoma, we examined the differences in endobronchial histology by measuring the frequency and percentage of HGD that develop in the large airways of mice treated with NTCU. Our studies indicate that mice sufficient in vitamin D3 (20 ng/mL serum 25D3) had fewer HGD lesions than mice on a vitamin D3-deficient diet (<4 ng/mL serum 25D3). We also found that systemic administration of calcitriol reduces the development of premalignant squamous lesions in vitamin D3-deficient mice. These findings suggest that vitamin D supplementation among subjects with deficiency may be an effective approach to block or reduce premalignant epithelial change in individuals at risk for lung cancer. With regard to this point, we propose that individuals diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) represent an appropriate population to target with a preventive vitamin D based intervention (40). COPD patients are at significantly elevated risk for developing lung cancer (41), and Vitamin D deficiency is a common problem in COPD patients: 31% have 25D3 levels <20 ng/mL, and 7% have severe deficiency (25D3 levels ≤ 10 ng/mL) (42).

The timing at which such supplementation to reverse low vitamin D levels is effective in the murine and clinical situations remains to be investigated. Our studies also fail to address the important question of vitamin D dose-response. How much vitamin D repletion is optimal? Studies in the AOM/DSS murine colon cancer model suggest that a dose-response relationship does exist; colonic dysplasia decreases as serum 25D3 levels increase from approximately 12 ng/mL to 60 ng/mL (43). The most striking effect was seen when mice with serum 25D3 levels of 12 ng/mL (100 IU/kg diet) were compared to those having a level of 30 ng/mL (400 IU/kg diet). In a separate study in the Apc+/min mouse model, no difference in the incidence of small intestinal tumors was observed between mice with serum 25D3 levels of 26 ng/mL and those with serum levels of 290 ng/mL (44). When considered together, these colon cancer prevention studies indicate a benefit of overcoming vitamin D deficiency, but that enhancing vitamin D levels in individuals with “adequate” levels (26-30 ng/mL) may be of only modest additional benefit. This is consistent with our observation that calcitriol decreases the frequency and percentage of HGD in vitamin D3-deficient mice but has little effect on the same parameters in vitamin D replete mice.

In addition to evaluating the development of premalignant lesions, we examined vitamin D-regulated pathways. Many of the actions of vitamin D signaling pathways are mediated by the binding of a heterodimer comprised of ligand-bound VDR with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to DNA to modulate gene expression (7). Menezes et al demonstrated that nuclear VDR staining increases in premalignant squamous lesions in lung (18). Other studies show that VDR staining is increased in premalignant and well-differentiated lesions in the breast and colon (18, 45, 46). In contrast, VDR protein expression is reduced in invasive and poorly differentiated breast and colon tumors. Low serum 25D3 serum content is associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC (15, 45, 46). Together these studies suggest that a loss of VDR signaling may lead to tumor progression. Our studies indicate that in vitamin D3-sufficient, but not D3-deficient mice there is increased nuclear VDR expression in the premalignant epithelial lesions. This suggests that sufficient vitamin D levels are required for VDR protein expression and active vitamin D signaling. Loss of vitamin D signaling results in a loss of the anti-tumor properties of vitamin D, leading to increased development of disease, as observed in the vitamin D3-deficient mice treated with NTCU (Fig 1 B, Table 3).

1,25D3 inhibits the growth of lung cancer cell lines at least in part by inducing cell cycle arrest (17, 47). We determined that proliferation (Ki67 labeling) is reduced in NTCU-treated vitamin D sufficient mice compared to NTCU-treated vitamin D deficient mice (Fig. 2F & 2G). In data not shown, we also noted that the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is increased in lesions from vitamin D sufficient mice. While Ki-67 may not be the ideal marker of efficacy of a chemopreventive agent’s ability to reduce cancer risk, it is a valid marker of proliferation, and increased proliferation is associated with increased cancer risk (48). Vitamin D deficiency was associated with increased proliferation as assessed by Ki-67 staining and increased progression of premalignant lesions.

The relationship between vitamin D status and the inflammatory response in these mice exposed to a lung carcinogen is also noteworthy. We observe persistent enhancement of inflammation both systemically and locally in NTCU-treated, vitamin D deficient mice. There is also an initial acute inflammatory response to NTCU treatment in vitamin D sufficient mice. Others have demonstrated the expression of CYP27B1 and local production of 1,25D3 in lung epithelial and immune cells (49). It is possible that in sufficient mice, where 25D3 levels are adequate, an influx of CYP27B1-expressing WBCs to the lung may increase local production of 1,25D3. This may result in increased modulation of VDR target genes that control inflammation. 1,25D3 has been shown to increase the expression of inhibitor of NFκB subunit beta (IKKβ) to inhibit NFκB activation (50). No such local production of 1,25D3 (and suppression of inflammation) would occur in vitamin D-deficient mice. Enhanced inflammation in the lungs is expected to promote the development of lung SCC, as shown in the mouse model of inactive kinase IKKα (37). The presence of heighted inflammation in vitamin D deficient mice is suggested by the elevation in IL-6 protein in the circulation and IL-6 gene expression in the lung. This study was not powered to examine the inflammatory response to carcinogen as it relates to disease. However, our initial analyses suggest that persistent inflammation and elevated IL-6 may be attenuated by vitamin D repletion and important targets for the chemoprevention of premalignant lesions in the airways of NTCU-treated mice.

In summary, our studies suggest that inflammation, proliferation, and progression of premalignant are enhanced in mice with vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D appears to slow the progression of disease. Further work in this area must identify the optimum time to correct vitamin D deficiency and the right populations to receive supplementation. Vitamin D may be more effective if administered in the early stages of disease progression, as opposed to later stages (14). Our data strongly support further pre-clinical studies and the development of clinical chemoprevention and intervention studies to further investigate the role of vitamin D in reducing the development and progression of premalignant lesions in lung SCC.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the laboratory of Dr. Barbara Foster and Dr. Mike Moser for technical support. Grant Support: NIH/NCCAM F31AT0006487 (Mazzilli, SA), NIH/NCI T32 CA009072 (Johnson,CS) NIH/NCI CA067267 (Johnson,CS), CCSG P30CA016056 (Trump, DL) and SPORE P50 CA090440 (Hershberger, PA Project Leader).

Abbreviations used

- 1,25D3

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, (calcitriol)

- 25D3

25-hydroxyvitamin D3, (calcifediol)

- AAALAC

Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- CK 5/6

Cytokeratin 5 & 6

- D

Vitamin D3 deficient

- DN

Vitamin D3 deficient +NTCU

- DN+C

Vitamin D3 deficient +NTCU +calcitriol

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid,

- E-PBS

EDTA phosphate buffered saline

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HGD

High-grade dysplasia

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IKKb

Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta

- LGD

Low-grade dysplasia

- NF-κb

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- NTCU

N-nitroso-tris-chloroethylurea

- RXR

Retinoid X receptor

- RBC

Red blood cells

- S

Vitamin D3 sufficient

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SN

Vitamin D3 sufficient +NTCU

- SN+C

Vitamin D3 sufficient +NTCU +calcitriol

- TTF-1

Thyroid transcription factor -1

- VDR

Vitamin D receptor

- Wk(s)

Week(s)

- WBC

White blood cells

Footnotes

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keith RL, Miller YE. Lung cancer chemoprevention: current status and future prospects. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2013;10:334–43. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.64. Epub 2013/05/22. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.64. PubMed PMID: 23689750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Zhang Z, Yan Y, Lemon WJ, LaRegina M, Morrison C, et al. A chemically induced model for squamous cell carcinoma of the lung in mice: histopathology and strain susceptibility. Cancer research. 2004;64:1647–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3273. Epub 2004/03/05. PubMed PMID: 14996723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, James M, Wen W, Lu Y, Szabo E, Lubet RA, et al. Chemopreventive effects of pioglitazone on chemically induced lung carcinogenesis in mice. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2010;9:3074–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0510. Epub 2010/11/04. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0510. PubMed PMID: 21045137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Zhang Z, Garbow JR, Rowland DJ, Lubet RA, Sit D, et al. Chemoprevention of lung squamous cell carcinoma in mice by a mixture of Chinese herbs. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:634–40. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0052. Epub 2009/07/09. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0052. PubMed PMID: 19584077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan J, Zhang Q, Li K, Liu Q, Wang Y, You M. Chemoprevention of lung squamous cell carcinoma by ginseng. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:530–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0366. Epub 2013/04/04. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0366. PubMed PMID: 23550152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan N, Afaq F, Kweon MH, Kim K, Mukhtar H. Oral consumption of pomegranate fruit extract inhibits growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. Cancer research. 2007;67:3475–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3941. Epub 2007/03/29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3941. PubMed PMID: 17389758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7:684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. Epub 2007/08/28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. PubMed PMID: 17721433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clinic proceedings Mayo Clinic. 2011;86:50–60. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0567. Epub 2011/01/05. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0567. PubMed PMID: 21193656; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3012634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96:53–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. Epub 2010/12/02. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. PubMed PMID: 21118827; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3046611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. Epub 2007/07/20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. PubMed PMID: 17634462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garland CF, Gorham ED, Mohr SB, Garland FC. Vitamin D for cancer prevention: global perspective. Annals of epidemiology. 2009;19:468–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.021. Epub 2009/06/16. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.021. PubMed PMID: 19523595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaney RP. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3:1535–41. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01160308. Epub 2008/06/06. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01160308. PubMed PMID: 18525006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng TY, Lacroix AZ, Beresford SA, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Zheng Y, et al. Vitamin D intake and lung cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013;98:1002–11. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.055905. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.055905. PubMed PMID: 23966428; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3778856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou W, Suk R, Liu G, Park S, Neuberg DS, Wain JC, et al. Vitamin d is associated with improved survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14:2303–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0335. PubMed PMID: 16214909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srinivasan M, Parwani AV, Hershberger PA, Lenzner DE, Weissfeld JL. Nuclear vitamin D receptor expression is associated with improved survival in non-small cell lung cancer. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2011;123:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.002. Epub 2010/10/20. doi: S0960-0760(10)00342-0 [pii] 10.016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.002. PubMed PMID: 20955794; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3010457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parise RA, Egorin MJ, Kanterewicz B, Taimi M, Petkovich M, Lew AM, et al. CYP24, the enzyme that catabolizes the antiproliferative agent vitamin D, is increased in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1819–28. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22058. Epub 2006/05/19. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22058. PubMed PMID: 16708384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SH, Chen G, King AN, Jeon CK, Christensen PJ, Zhao L, et al. Characterization of vitamin D receptor (VDR) in lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2012;77:265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.04.010. Epub 2012/05/09. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.04.010. PubMed PMID: 22564539; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3396768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menezes RJ, Cheney RT, Husain A, Tretiakova M, Loewen G, Johnson CS, et al. Vitamin D receptor expression in normal, premalignant, and malignant human lung tissue. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17:1104–10. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2713. Epub 2008/05/17. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2713. PubMed PMID: 18483332; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2748868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton R, O’Connell MA. Vitamin D: potential in the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Anticancer research. 2012;32:211–21. Epub 2012/01/04. PubMed PMID: 22213310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JM, Yanagawa J, Peebles KA, Sharma S, Mao JT, Dubinett SM. Inflammation in lung carcinogenesis: new targets for lung cancer chemoprevention and treatment. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2008;66:208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.004. Epub 2008/02/29. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.004. PubMed PMID: 18304833; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2483429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokuda N, Levy RB. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates phagocytosis but suppresses HLA-DR and CD13 antigen expression in human mononuclear phagocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;211:244–50. doi: 10.3181/00379727-211-43967. Epub 1996/03/01. PubMed PMID: 8633104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. Epub 2006/02/25. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. PubMed PMID: 16497887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann EH, Chambers ES, Pfeffer PE, Hawrylowicz CM. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of vitamin D relevant to respiratory health and asthma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014;1317:57–69. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12410. Epub 2014/04/18. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12410. PubMed PMID: 24738964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan AV, Feldman D. Mechanisms of the anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions of vitamin D. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2011;51:311–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100611. Epub 2010/10/13. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100611. PubMed PMID: 20936945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorman S, Weeden CE, Tan DH, Scott NM, Hart J, Foong RE, et al. Reversible control by vitamin D of granulocytes and bacteria in the lungs of mice: an ovalbumin-induced model of allergic airway disease. PloS one. 2013;8:e67823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067823. Epub 2013/07/05. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067823. PubMed PMID: 23826346; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3691156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudish TM, Opincariu LI, Mozer AB, Johnson MS, Cleaver TG, Malkoski SP, et al. N-nitroso-tris-chloroethylurea induces premalignant squamous dysplasia in mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:283–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0257. Epub 2011/11/17. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0257. PubMed PMID: 22086679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Council NR. Nutrient Requirements of the Mouse. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals. NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS; Washington (DC): 1995. pp. 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH protocols. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4986. pdb prot4986. Epub 2008/01/01. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4986. PubMed PMID: 21356829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrick DT, Kittelson J, Winterhalder R, Kotantoulas G, Ingeberg S, Keith RL, et al. Analysis of c-ErbB1/epidermal growth factor receptor and c-ErbB2/HER-2 expression in bronchial dysplasia: evaluation of potential targets for chemoprevention of lung cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12:2281–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2291. Epub 2006/04/13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2291. PubMed PMID: 16609045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rio DC, Ares M, Jr., Hannon GJ, Nilsen TW. Purification of RNA using TRIzol (TRI reagent) Cold Spring Harbor protocols. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5439. pdb prot5439. Epub 2010/06/03. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5439. PubMed PMID: 20516177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. Epub 2008/06/13. PubMed PMID: 18546601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnan AV, Swami S, Feldman D. Equivalent anticancer activities of dietary vitamin D and calcitriol in an animal model of breast cancer: importance of mammary CYP27B1 for treatment and prevention. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2013;136:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.08.005. Epub 2012/09/04. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.08.005. PubMed PMID: 22939886; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3554854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabstein LS, Peters RL, Spahn GJ. Spontaneous tumors and pathologic lesions in SWR-J mice. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1973;50:751–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/50.3.751. Epub 1973/03/01. PubMed PMID: 4732946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huet T, Laverny G, Ciesielski F, Molnar F, Ramamoorthy TG, Belorusova AY, et al. A vitamin d receptor selectively activated by gemini analogs reveals ligand dependent and independent effects. Cell reports. 2015;10:516–26. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.045. Epub 2015/01/27. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.045. PubMed PMID: 25620699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girgis CM, Mokbel N, Cha KM, Houweling PJ, Abboud M, Fraser DR, et al. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is expressed in skeletal muscle of male mice and modulates 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) uptake in myofibers. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3227–37. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1016. Epub 2014/06/21. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1016. PubMed PMID: 24949660; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4207908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–57. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. PubMed PMID: 24705652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Z, Jiang Q, Willette-Brown J, Xi S, Zhu F, Burkett S, et al. The pivotal role of IKKalpha in the development of spontaneous lung squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer cell. 2013;23:527–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.009. Epub 2013/04/20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.009. PubMed PMID: 23597566; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3649010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohr SB, Garland CF, Gorham ED, Grant WB, Garland FC. Could ultraviolet B irradiance and vitamin D be associated with lower incidence rates of lung cancer? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:69–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.052571. doi: 62/1/69 [pii] 10.136/jech.2006.052571. PubMed PMID: 18079336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mernitz H, Smith DE, Wood RJ, Russell RM, Wang XD. Inhibition of lung carcinogenesis by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 9-cis retinoic acid in the A/J mouse model: evidence of retinoid mitigation of vitamin D toxicity. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2007;120:1402–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22462. Epub 2007/01/06. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22462. PubMed PMID: 17205520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martineau AR, James WY, Hooper RL, Barnes NC, Jolliffe DA, Greiller CL, et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ViDiCO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2015;3:120–30. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70255-3. Epub 2014/12/06. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70255-3. PubMed PMID: 25476069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brothers JF, Hijazi K, Mascaux C, El-Zein RA, Spitz MR, Spira A. Bridging the clinical gaps: genetic, epigenetic and transcriptomic biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer in the post-National Lung Screening Trial era. BMC medicine. 2013;11:168. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-168. Epub 2013/07/23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-168. PubMed PMID: 23870182; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3717087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kunisaki KM, Niewoehner DE, Singh RJ, Connett JE. Vitamin D status and longitudinal lung function decline in the Lung Health Study. The European respiratory journal. 2011;37:238–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146509. Epub 2010/07/03. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146509. PubMed PMID: 20595151; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3070416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hummel DM, Thiem U, Hobaus J, Mesteri I, Gober L, Stremnitzer C, et al. Prevention of preneoplastic lesions by dietary vitamin D in a mouse model of colorectal carcinogenesis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2013;136:284–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.09.003. Epub 2012/09/18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.09.003. PubMed PMID: 22982628; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3695567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irving AA, Halberg RB, Albrecht DM, Plum LA, Krentz KJ, Clipson L, et al. Supplementation by vitamin D compounds does not affect colonic tumor development in vitamin D sufficient murine models. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2011;515:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.08.011. Epub 2011/09/13. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.08.011. PubMed PMID: 21907701; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3295581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopes N, Sousa B, Martins D, Gomes M, Vieira D, Veronese LA, et al. Alterations in Vitamin D signalling and metabolic pathways in breast cancer progression: a study of VDR, CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 expression in benign and malignant breast lesions. BMC cancer. 2010;10:483. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-483. Epub 2010/09/14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-483. PubMed PMID: 20831823; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2945944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matusiak D, Murillo G, Carroll RE, Mehta RG, Benya RV. Expression of vitamin D receptor and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1{alpha}-hydroxylase in normal and malignant human colon. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14:2370–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0257. Epub 2005/10/11. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0257. PubMed PMID: 16214919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Q, Kanterewicz B, Buch S, Petkovich M, Parise R, Beumer J, et al. CYP24 inhibition preserves 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) anti-proliferative signaling in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;355:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.006. Epub 2012/03/06. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.006. PubMed PMID: 22386975; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3312998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller YE, Blatchford P, Hyun DS, Keith RL, Kennedy TC, Wolf H, et al. Bronchial epithelial Ki-67 index is related to histology, smoking, and gender, but not lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2007;16:2425–31. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0220. Epub 2007/11/17. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0220. PubMed PMID: 18006932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfeffer PE, Hawrylowicz CM. Vitamin D and lung disease. Thorax. 2012;67:1018–20. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202139. Epub 2012/09/01. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202139. PubMed PMID: 22935474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Zhang J, Ge X, Du J, Deb DK, Li YC. Vitamin D receptor inhibits nuclear factor kappaB activation by interacting with IkappaB kinase beta protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:19450–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467670. Epub 2013/05/15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467670. PubMed PMID: 23671281; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3707648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.