Physician practices are increasingly integrating with hospitals.1 For physicians, the expansion of accountable care organization contracts centered on providers taking responsibility for population spending and quality makes independent practice more challenging. For hospitals and health systems, acquiring practices helps them control referral patterns, coordinate care, and improve their bargaining power with payers.

In 2010, based on recommendations from the American Medical Association and a national practice expense survey of physicians, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reduced fees for cardiology services, focusing on those delivered in the office setting.2 For example, payment for a myocardial perfusion image in the office was cut 26%, compared to 5% in the hospital outpatient department (HOPD). That for an echocardiogram was cut 16% in the office, compared to a 3% increase in the HOPD setting. This widened the already existing payment gap favoring HOPDs—by 2013, an echocardiogram cost Medicare 141% more in HOPDs than in the office.3

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) projected a surge of integration in response to physician office fee reductions, with cardiologists exchanging practice ownership for more predictable salaries as hospital employees.4 We analyzed trends in cardiologist-hospital integration.

Methods

We analyzed 2007–2012 medical claims in a continuously-enrolled national sample of traditional Medicare beneficiaries and commercially-insured individuals from Truven Medicare and Commercial databases. We measured cardiologist-hospital integration by calculating the share of volume billed in HOPDs. This captures both shifts in care to HOPDs and changes in practice patterns induced by physician-hospital integration. We focused on 3 affected services—myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms.3 We expected shares of HOPD volume to increase.

We used segmented regression to assess changes in integration growth after the physician office fee cut. Independent variables included beneficiary age and sex, time trend, a post-intervention indicator, and the interaction between post-intervention and trend. We also included quarter and metropolitan statistical area (MSA) fixed effects. Standard errors were clustered by MSA.

Results

Our sample included 806,266 Medicare beneficiaries averaging 75.7 years of age, 53.3% female, representing all states, and 12,567,069 commercially-insured individuals between 55 and 64 years of age who were 52.8% female, with a similar geographic distribution.

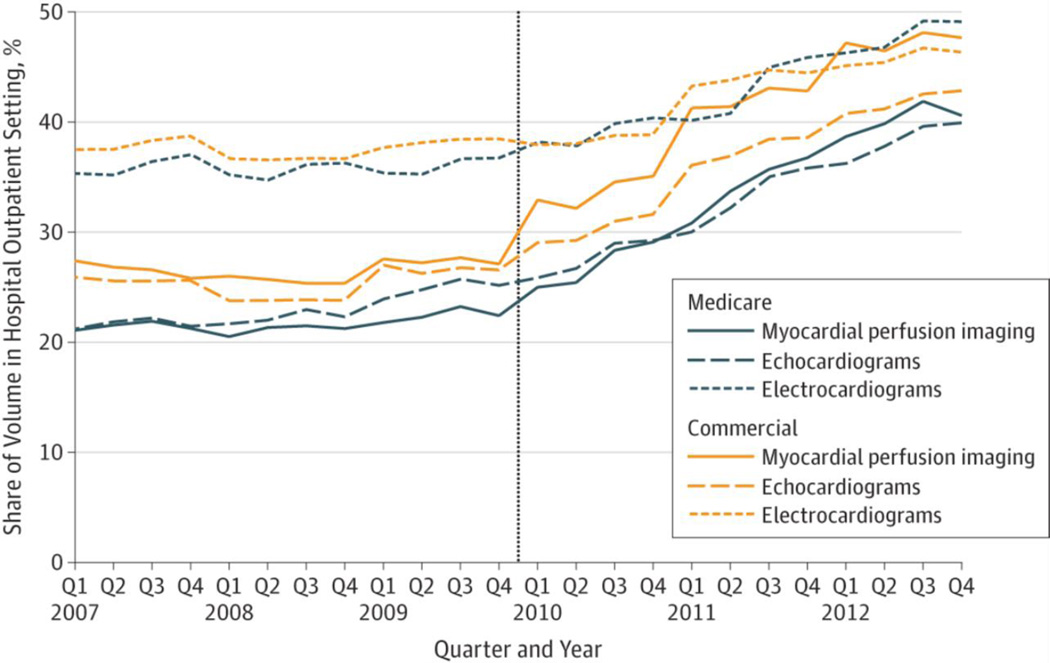

Across all services, prices favored the HOPD setting after 2010 (Table). The shares of volume in the HOPD setting also increased after 2010 (Figure). Growth in the HOPD share was 5.9, 3.9, and 2.7 percentage points per year (p<0.001) faster after 2010 compared to before 2010 for MPIs, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms, respectively. The overall volume of echocardiograms and electrocardiograms per beneficiary continued to increase after the fee cut, while that for MPI decreased slightly (Table).

Table.

Price, Volume, and Site of Care for Cardiology Services Before and After 2010 Medicare Fee Cuts*

| Traditional Medicare Beneficiaries (N=806,266) |

Commercially-Insured Individuals (N=12,567,069) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Fee Cut (2007–09) |

After Fee Cut (2010–12) |

Change | Before Fee Cut (2007–09) |

After Fee Cut (2010–12) |

Change | |

| Myocardial Perfusion Imaging | ||||||

| Average Price ($) | ||||||

| Physician Office | 685.84 | 547.22 | −138.62 | 764.62 | 591.11 | −173.51 |

| HOPD Total | 1790.50 | 1954.02 | 163.52 | 1773.19 | 1899.59 | 126.40 |

| HOPD Professional Fee | 153.97 | 98.65 | −55.32 | 186.38 | 134.59 | −51.79 |

| HOPD Facility Fee | 1636.53 | 1855.37 | 218.84 | 1586.81 | 1765 | 178.19 |

| Volume (per 100 enrollees per year) | ||||||

| Total | 9.2 | 8.0 | −1.2 | 5.8 | 4.3 | −1.5 |

| Physician Office | 6.9 | 5.1 | −1.8 | 4.3 | 2.5 | −1.7 |

| HOPD | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.2 |

| Adjusted HOPD Share (%) | 21.1 | 32.4 | 11.3 | 24.0 | 35.5 | 11.5 |

| Growth (%-points/year) (P value) | 0.6 (0.70) | 6.4 (<0.001) | 5.9 (<0.001) | 0.3 (0.001) | 6.7 (<0.001) | 6.4 (<0.001) |

| Echocardiograms | ||||||

| Average Price ($) | ||||||

| Physician Office | 357.32 | 289.53 | −67.79 | 399.74 | 330.3 | −69.44 |

| HOPD Total | 951.14 | 1057.95 | 106.81 | 969.81 | 1088.7 | 118.89 |

| HOPD Professional Fee | 94.33 | 83.32 | −11.01 | 108.18 | 111.21 | 3.03 |

| HOPD Facility Fee | 856.81 | 974.63 | 117.82 | 861.63 | 977.49 | 115.86 |

| Volume (per 100 enrollees per year) | ||||||

| Total | 18.4 | 19.0 | 0.6 | 8.9 | 8.6 | −0.3 |

| Physician Office | 12.4 | 11.1 | −1.3 | 6.6 | 5.4 | −1.2 |

| HOPD | 3.7 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Adjusted HOPD Share (%) | 22.1 | 31.7 | 9.6 | 23.1 | 32.5 | 9.4 |

| Growth (%-points/year) (P value) | 1.2 (0.04) | 5.1 (<0.001) | 3.9 (<0.001) | 0.3 (<0.001) | 5.8 (<0.001) | 5.5 (<0.001) |

| Electrocardiograms | ||||||

| Average Price ($) | ||||||

| Physician Office | 41.53 | 37.23 | −4.30 | 48.88 | 42.10 | −6.78 |

| HOPD Total | 186.49 | 212.45 | 25.96 | 186.19 | 211.20 | 25.01 |

| HOPD Professional Fee | 16.94 | 17.18 | 0.24 | 20.92 | 22.45 | 1.53 |

| HOPD Facility Fee | 169.55 | 195.27 | 25.72 | 165.27 | 188.75 | 23.48 |

| Volume (per 100 enrollees per year) | ||||||

| Total | 92.9 | 100.6 | 7.7 | 54.8 | 53.7 | −1.2 |

| Physician Office | 52.2 | 50.5 | −1.6 | 33.3 | 29.3 | −4.0 |

| HOPD | 29.1 | 38.4 | 9.3 | 18.5 | 20.8 | 2.3 |

| Adjusted HOPD Share (%) | 29.9 | 35.2 | 5.3 | 27.4 | 30.0 | 2.6 |

| Growth (%-points/year) (P value) | −0.1 (0.23) | 2.6 (<0.001) | 2.7 (<0.001) | 0.0 (<0.001) | 2.4 (<0.001) | 2.4 (<0.001) |

HOPD denotes hospital outpatient department. Average prices are derived from the most frequently billed services within a category. Sensitivity analyses supported our main estimates. We examined endoscopies, which can be provided in the office or HOPD but did not under go a fee cut, and found that its HOPD share did not significantly change after 2010. We also examined office visits, whose HOPD share growth before 2010 was lower than those of the cardiovascular categories, suggesting that cardiologists were not integrating faster at baseline. For a subset of the population with risk scores available, controlling for risk did not meaningfully change the results. All enrollees were continuously enrolled for 6 years and the population represented all states (10% Northeast, 36% North Central, 30% South, 23% West). Results were robust to loosening this restriction. Physician office and HOPD volume comprise the great majority of, but do not equal, total volume, as there are other location codes available that are infrequently billed. Results are reported with two-tailed P values.

Figure.

Shares of Services Billed in the Hospital Outpatient Department Setting*

* The vertical line represents the onset of 2010 Medicare fee cuts. MPI = myocardial perfusion imaging, Echo = echocardiograms, and ECG = electrocardiograms. The Truven Medicare and Commercial databases comprise large convenience samples of Medicare beneficiaries with Medicare Supplemental coverage for whom Medicare is the primary payer, as well as adults and families with commercial insurance from large U.S. employers, respectively.

Aggregate analyses of all cardiovascular imaging and cardiovascular medicine services produced qualitatively similar results. Similar results were also found in commercial populations, suggesting that integration was associated with comparable effects across payers (Table).

Discussion

Integration accelerated after the fee cuts. This is consistent with the 2010 ACC Practice Consensus, which found that 40% of cardiologists planned to integrate with hospitals due to the fee cuts and 13% were considering it.5 The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission estimated that if cardiology imaging alone continued to migrate to HOPDs, nearly all would be provided there by 2021 costing an additional $1.1 billion per year to Medicare and $290 million per year in beneficiary cost-sharing due to higher prices for facility-based services.3

HOPDs may be more expensive than office settings due to the costs of licensing requirements, ancillary services, maintaining standby capacity, and treating more complex patients.3 However, if equivalent quality care could be delivered in the office, the case for paying the higher fee may be more difficult to justify. Moreover, while higher HOPD payments may be covering higher hospital costs, they may also be passed through to physicians through higher salaries. Ultimately, integration may offset savings that fee cuts were intended to achieve, both because facility-based fees are higher and because of higher prices due to market power.

Our results may not be causal or generalizable. Other market forces could have also encouraged integration, such as hospitals acquiring practices to preserve their referral base under new payment models and the rising costs of independent practice, including malpractice premiums, infrastructure costs (e.g. electronic medical records), and costs of meeting new quality reporting or performance goals. Moreover, integration has not been limited to cardiology, supporting the potential effect of broader secular factors. At the service level, the effect of any fee cut depends on its magnitude, the previous fees in each setting, and changes in the volume of affected and substitute services across different sites of care.

Amidst growing recognition of payment disparities across sites of care, policies that aim to equalize payments across settings have received increasing attention. The President’s fiscal year 2016 budget proposes site neutral payments, estimated to save nearly $29.5 billion over 10 years. If fee cuts did indeed lead to hospital acquisition of physician practices, then narrowing the payment gap may lead to less physician-hospital integration, which might in turn limit price increases from market power.6

Acknowledgment

Supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (F30 AG039175) to Dr. Song, a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Health Care Financing Organization (71408) to Dr. McWilliams and Dr. Chernew, and a grant from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to Mr. Wallace (1144152).

Role of the Sponsor

The National Institute on Aging, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Health Care Financing Organization, the National Science Foundation, and organizations to which the authors are affiliated had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Zirui Song has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Jacob Wallace has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Hannah Neprash has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Michael R. McKellar has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

J. Michael McWilliams has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Michael E. Chernew has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Isaacs SL, Jellinek PS, Ray WL. The independent physician--going, going. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 12;360(7):655–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0808076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Program; Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2010. Federal Register. 2009 Nov 25; [PubMed]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Washington, DC: 2013. Jun, Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brindis R, Rodgers GP, Handberg EM. President's page: team-based care: a solution for our health care delivery challenges. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Mar 1;57(9):1123–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Cardiology. ACC 2010 practice census. 2010 Oct 7; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014 May 33;(5):756–763. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]