Abstract

Ruminants are known to harbour a vast and diverse microbial community that functions in utilizing the fibrous and starchy feedstuffs. The microbial fermentation of fibrous and starchy feed is carried out by different groups of microbiota, which function in synergistic mechanism. The exploration of the shift in carbohydrate utilizing microbial community with the change in diet will reveal the efficient role of that group of microbial community in particular carbohydrate utilization. The present study explains the shifts in microbial enzymes for carbohydrate utilization with the change in the feed proportions and its correlation with the microbial community abundance at that particular treatment. The sequencing data of the present study is submitted to NCBI SRA with experiment accession IDs (ERX162128, ERX162129, ERX162130, ERX162131, ERX162139, ERX162134, ERX162140, ERX162141, ERX197218, ERX197219, ERX197220, ERX197221, ERX162158, ERX162159, ERX162160, ERX162161, ERX162176, ERX162164, ERX162165, ERX162166, ERX162167, ERX162168, ERX162169, ERX162177).

Keywords: Rumen, Dry roughage, Maltose, Xylose, Ion Torrent PGM

| Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Organism | NA (metagenome) |

| Sex | N/A |

| Sequencer | Ion Torrent PGM |

| Data format | Analysed |

| Experimental factors | Three dietary regimes (different proportions of dry roughage and concentrate) were given to Mehsani buffalo |

| Experimental features | Metagenome sequencing of the ruminal microbes from Mehsani buffalo fed on three dietary treatments to explore carbohydrate metabolism shifts in rumen |

| Consent | Allowed for reuse citing original authors |

| Sample source location | Sardar Krushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University, Gujarat, India |

1. Direct link to deposited data

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162128

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162129

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162130

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162131

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162139

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162134

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162140

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162141

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX197218

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX197219

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX197220

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX197221

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162158

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162159

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162160

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162161

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162176

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162164

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162165

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162166

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162167

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX162168

2. Introduction

Ruminants contribute to a significant proportion of the domesticated animal species worldwide, and are the best adapted to the utilization and digestion of the plant cell wall [1]. Nutrition to an animal offers a means of making rapid change in milk composition i.e., concentration of milk fat, where the amount of roughage, forage: concentrate ratio, carbohydrate composition are the key factors to be taken cared of [2]. Improvement in the ability of the rumen microbiota to degrade plant cell wall is generally highly desirable and usually leads to improved animal performance [3].

The understanding of the carbohydrate utilization in ruminants is now expanding with the advent in molecular technologies. The culture dependent methods have remain pitfall in explaining microbial metabolism carried out in the rumen. After the foundation of the term “Metagenomics” [4], the technique had now became superior in the field of rumen microbial ecology.

The recent developments in sequencing technologies have allowed the researchers to reach the deeper layer of the microbial community. Here in the present study, Ion Torrent PGM was used for the sequencing of the rumen metagenomes [5]. Four animals were given three different treatments where the dry roughage to concentrate ratio was changed (50%:50%, 75%:25% and 100%). The carbohydrate metabolism carried out by rumen microbiota was explored in this study.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Sample collection

Total 4 Mehsani breed of buffaloes were hired at Sardar Krushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University. All animals were given dry roughage as diet in different proportions of concentrates. In the first treatment (M1), 50% roughage and 50% concentrate was given as diet. The second treatment (M2) consists of 75% roughage and 25% concentrate. Whereas third treatment (M3) consisted 100% roughage. Each treatment was given for six weeks. After the end of the six weeks of each treatment, the rumen sample was collected using stomach tube [6] and then filtered using muslin cloth to separate liquid and solid fractions. In total 24 samples (4 animals × 3 treatments × 2 fractions = 24 samples) were collected and stored at − 20 °C.

3.2. DNA extraction and metagenome sequencing

Total DNA from rumen sample was extracted using QIAGEN DNA stool kit [7]. ~ 300 ng of total DNA was used for library preparation of Ion Torrent PGM platform. A total of 24 barcoded libraries were prepared and sequencing run was carried out on 316 chips of Ion Torrent PGM platform.

3.3. Metagenome data analysis

The sequencing data are available at NCBI with SRA experiment IDs (ERX162128, ERX162129, ERX162130, ERX162131, ERX162139, ERX162134, ERX162140, ERX162141, ERX197218, ERX197219, ERX197220, ERX197221, ERX162158, ERX162159, ERX162160, ERX162161, ERX162176, ERX162164, ERX162165, ERX162166, ERX162167, ERX162168, ERX162169, ERX162177).The sequencing data were also uploaded to MG-RAST web server [8]. The functional classification of the sequences was done by using SEED database at 80% identity cutoff [9]. The subsystem classification was carried out at level 1, the major category from which was further sub-classified at level 2 for each metagenome groups.

4. Results and discussion

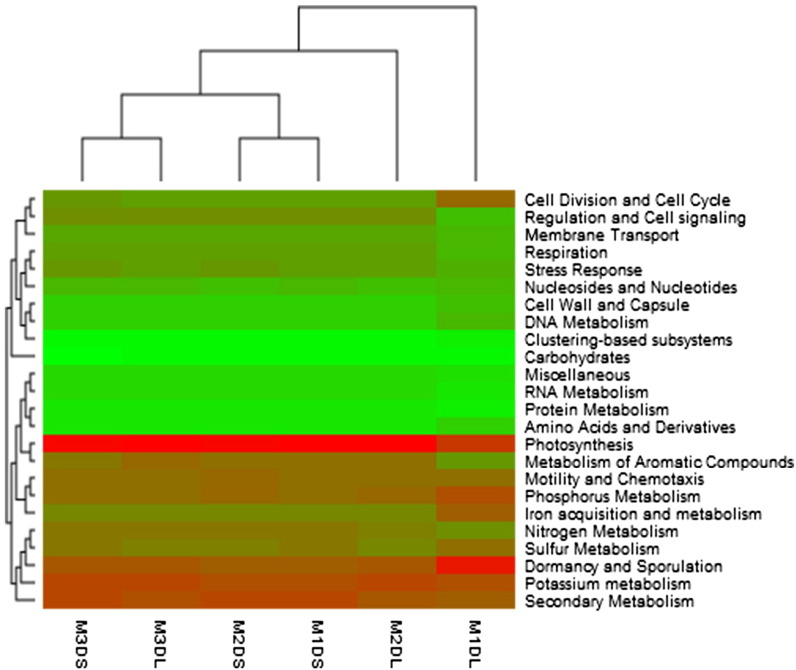

The assignment of the sequences to SEED database revealed that at subsystem level, out of the 24 subsystems identified, the genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism were found to be most abundant in each metagenome groups (Fig. 1). So, that particular category of subsystem was sub-classified at further level. By sub-classifying, we found that the genes associated with sugar utilization in thermogales were more abundant for both liquid and solid fractions (Table 1, Table 2). This particular category possesses the enzymes involved in formation of the system for sugar transport and its utilization. The second most dominant category found in our dataset was one carbon metabolism which included the genes involved in serine-glyoxylate cycle. It was found to be increased with the increment in the roughage for liquid fraction (M1DL = 8.11%, M2DL = 8.59%, M3DL = 8.74%) whereas, for solid fraction it was found to be in similar abundance for M2DS and M3DS (7.92%) as compared to M1DS group (7.65%). The category that belonged to enzymes for di and oligo saccharide utilization was found which is composed by the genes related to maltose/maltodextrin utilization, xylose utilization, l-rhamnose utilization, l-arabinose utilization, lactose utilization, mannose utilization etc. The genes linked to maltose utilization decreased in both the fractions with the increment in the roughage. Whereas, the genes associated with the mannose and xylose utilization increased with the increment in the roughage in both the fractions. The genes predicted for carbohydrate hydrolases decreased with the increment in the roughage for liquid fraction and increased in case of the solid fraction. Moreover, the genes related to dehydrogenase complexes increased with the increment in the roughage for both the fractions.

Fig. 1.

Subsystem level classification of the metagenomes of dry roughage groups in liquid and solid fractions.

Table 1.

Subsystem classification at level 3 of carbohydrate metabolism in liquid fraction.

| M1DL (n = 4) |

M2DL (n = 4) |

M3DL (n = 4) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | SEM | Mean (%) | SEM | Mean (%) | SEM | |

| Sugar utilization in thermotogales | 11.81 | 0.31 | 13.46 | 0.23 | 12.79 | 0.30 |

| Serine-glyoxylate cycle | 8.11 | 0.20 | 8.59 | 0.21 | 8.74 | 0.21 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 4.68 | 0.21 | 4.84 | 0.18 | 5.61 | 0.20 |

| d-Galacturonate and d-glucuronate utilization | 3.82 | 0.15 | 4.08 | 0.11 | 3.46 | 0.08 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, including archaeal enzymes | 3.41 | 0.21 | 3.67 | 0.06 | 4.24 | 0.16 |

| Lactose and galactose uptake and utilization | 3.17 | 0.15 | 3.65 | 0.17 | 3.41 | 0.10 |

| Calvin–Benson cycle | 3.12 | 0.10 | 2.81 | 0.10 | 3.17 | 0.04 |

| Acetyl-CoA fermentation to butyrate | 2.97 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.10 |

| Maltose and maltodextrin utilization | 2.68 | 0.16 | 2.68 | 0.05 | 2.61 | 0.05 |

| Pyruvate metabolism II: acetyl-CoA, acetogenesis from pyruvate | 2.66 | 0.15 | 1.44 | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.08 |

| Pyruvate metabolism I: anaplerotic reactions, PEP | 2.50 | 0.15 | 2.76 | 0.05 | 3.11 | 0.17 |

| Entner–Doudoroff pathway | 2.49 | 0.07 | 2.55 | 0.03 | 2.94 | 0.11 |

| Xylose utilization | 2.10 | 0.15 | 2.94 | 0.10 | 2.67 | 0.13 |

| Fermentations: lactate | 2.02 | 0.08 | 1.27 | 0.06 | 1.26 | 0.10 |

| Glycogen metabolism | 2.02 | 0.09 | 2.14 | 0.12 | 2.08 | 0.10 |

| Lactose utilization | 1.97 | 0.09 | 2.20 | 0.14 | 1.92 | 0.08 |

| l-Rhamnose utilization | 1.91 | 0.07 | 2.03 | 0.08 | 1.53 | 0.05 |

| Beta-glucoside metabolism | 1.81 | 0.10 | 1.83 | 0.05 | 1.71 | 0.09 |

| TCA cycle | 1.65 | 0.08 | 1.57 | 0.13 | 1.83 | 0.06 |

| l-Arabinose utilization | 1.62 | 0.09 | 1.76 | 0.06 | 1.56 | 0.03 |

| Mannose metabolism | 1.59 | 0.07 | 1.63 | 0.02 | 2.05 | 0.07 |

| Fermentations: mixed acid | 1.53 | 0.07 | 1.80 | 0.06 | 1.74 | 0.10 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 1.48 | 0.06 | 1.75 | 0.06 | 1.79 | 0.05 |

| Propionyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA module | 1.39 | 0.05 | 1.53 | 0.14 | 1.55 | 0.08 |

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and raffinose utilization | 1.38 | 0.06 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 1.48 | 0.04 |

| Photorespiration (oxidative C2 cycle) | 1.34 | 0.05 | 1.29 | 0.08 | 1.57 | 0.00 |

| Glyoxylate bypass | 1.23 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.50 | 0.02 |

| Butanol biosynthesis | 1.15 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 0.02 | 1.17 | 0.06 |

| Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase | 1.14 | 0.08 | 1.41 | 0.05 | 1.70 | 0.03 |

| Propanediol utilization | 1.14 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.02 |

| Acetone butanol ethanol synthesis | 1.09 | 0.05 | 1.42 | 0.06 | 1.51 | 0.08 |

| l-Fucose utilization | 1.05 | 0.05 | 1.40 | 0.04 | 1.12 | 0.02 |

| Deoxyribose and deoxynucleoside catabolism | 1.03 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.03 |

Table 2.

Subsystem classification at level 3 of carbohydrate metabolism in solid fraction.

| M1DS (n = 4) |

M2DS (n = 4) |

M3DS (n = 4) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | SEM | Mean (%) | SEM | Mean (%) | SEM | |

| Sugar utilization in thermotogales | 12.64 | 0.16 | 12.98 | 0.29 | 13.15 | 0.23 |

| Serine-glyoxylate cycle | 7.65 | 0.47 | 7.92 | 0.06 | 7.92 | 0.20 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 5.30 | 0.22 | 5.35 | 0.10 | 5.01 | 0.16 |

| d-Galacturonate and d-glucuronate utilization | 2.83 | 0.12 | 3.24 | 0.17 | 3.45 | 0.15 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, including archaeal enzymes | 4.12 | 0.21 | 4.19 | 0.09 | 3.82 | 0.11 |

| Lactose and galactose uptake and utilization | 3.10 | 0.08 | 3.29 | 0.12 | 3.14 | 0.14 |

| Calvin–Benson cycle | 3.15 | 0.07 | 3.05 | 0.11 | 2.96 | 0.09 |

| Acetyl-CoA fermentation to butyrate | 1.44 | 0.06 | 1.22 | 0.08 | 1.46 | 0.15 |

| Maltose and maltodextrin utilization | 3.36 | 0.08 | 2.99 | 0.01 | 2.92 | 0.08 |

| Pyruvate metabolism II: acetyl-CoA, acetogenesis from pyruvate | 1.38 | 0.08 | 1.42 | 0.06 | 1.45 | 0.09 |

| Pyruvate metabolism I: anaplerotic reactions, PEP | 2.90 | 0.18 | 3.03 | 0.13 | 2.62 | 0.10 |

| Entner–Doudoroff pathway | 2.83 | 0.11 | 2.69 | 0.05 | 2.72 | 0.06 |

| Xylose utilization | 2.30 | 0.10 | 2.47 | 0.13 | 2.88 | 0.16 |

| Fermentations: lactate | 1.43 | 0.10 | 1.46 | 0.10 | 1.38 | 0.09 |

| Glycogen metabolism | 2.56 | 0.06 | 2.16 | 0.06 | 2.05 | 0.04 |

| Lactose utilization | 1.59 | 0.06 | 1.79 | 0.10 | 1.73 | 0.10 |

| l-Rhamnose utilization | 1.34 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 0.06 | 1.34 | 0.10 |

| Beta-glucoside metabolism | 2.03 | 0.06 | 1.88 | 0.09 | 1.96 | 0.05 |

| TCA cycle | 1.72 | 0.10 | 1.68 | 0.05 | 1.88 | 0.07 |

| l-Arabinose utilization | 1.56 | 0.06 | 1.73 | 0.06 | 1.99 | 0.07 |

| Mannose metabolism | 1.68 | 0.11 | 1.66 | 0.02 | 1.86 | 0.11 |

| Fermentations: mixed acid | 1.86 | 0.07 | 1.83 | 0.11 | 1.95 | 0.04 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 2.12 | 0.07 | 2.02 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 0.10 |

| Propionyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA module | 1.13 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 0.07 | 1.24 | 0.04 |

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and raffinose utilization | 1.94 | 0.10 | 1.84 | 0.06 | 1.83 | 0.04 |

| Photorespiration (oxidative C2 cycle) | 1.51 | 0.05 | 1.48 | 0.07 | 1.45 | 0.09 |

| Glyoxylate bypass | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| Butanol biosynthesis | 1.43 | 0.03 | 1.28 | 0.05 | 1.54 | 0.02 |

| Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase | 1.88 | 0.08 | 1.93 | 0.16 | 1.86 | 0.04 |

| Propanediol utilization | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| Acetone butanol ethanol synthesis | 1.60 | 0.10 | 1.45 | 0.02 | 1.49 | 0.06 |

| l-Fucose utilization | 1.03 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

| Deoxyribose and deoxynucleoside catabolism | 1.10 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.01 |

As observed by Brulc et al., the bovine rumen harboured the functional genes associated with carbohydrate utilization [10]. A study by Wang et al. revealed that majority of the genes were associated with the carbohydrate metabolism (11%) [11]. In the present study, the genes involved in the sugar utilization were observed to be predominated. This particular category is composed of different sugar binding proteins and sugar transporter systems. This finding shows that the ruminal microbiota starts acting on the ingested food within 2 h of the feeding and start materializing that food into sugars to be taken up by the host. Moreover, we found the glycolysis and gluconeogenesis related enzymes both for bacteria and archaea that increased with the increment in the roughages. Glycolysis is the most common pathway for the conversion of glucose-6-P into pyruvate which generates ATP and metabolites for essential cellular processes. Whereas, essential glycolytic intermediates are synthesized via gluconeogenesis, the process which is reversion of glycolysis. However, this particular pathway is found to be well conserved in the bacteria and eukaryotes, the archaea have developed unique variants for this pathway which includes zero or very low ATP yields; reduction of ferredoxin rather than NADH; many unusual glycolytic enzymes, including ADP-dependent gluco- and phosphofructo-kinases, non-orthologous PGMs, FBAs, non-phosphorylating GAP dehydrogenases, etc. [12]. In the present study, the enzymes involved in this pathway were found to be more or less similar in their abundance in both bacteria and archaea. In the present study, the genes involved in maltose utilization decreased with the increment in the roughage, which correlates with the fact that with the increment in roughage and decrease in starch rich concentrate, the maltose and maltodextrin utilization decreases, as they are produced after partial hydrolysis of starch. It has been found that Prevotella ruminicola is a major amylolytic organism in the rumen and produces high amylases, which cleaves starch into maltose and maltodextrins [13]. A previous study, done by [14], also showed that the abundance of genus Prevotella decreases with the increment in the dry roughage proportion. On the other hand, the abundance of the enzymes involved in pentose sugar utilization like xylose and arabinoses increases with the increment in the roughages. It has been found that Ruminococcus albus is an important fibrolytic ruminal bacteria which degrades hemicelluloses and ferments them to pentose sugars [15]. As per our previous study in the same breed, we have found that the abundance of Ruminococcus genus increases with the increment in the roughage [14]. Thus, this study provides the deep insights into the metabolism carried out by ruminal bacteria and its functional relevance. The information gained by this study can be helpful in developing the diet formulation for the better nutrition of livestock.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Niche area of excellence program funded by Indian Council of Agricultural Research (BH-203020), New Delhi, India.

Contributor Information

Nidhi R. Parmar, Email: ndhi.prmr1@gmail.com.

Chaitanya G. Joshi, Email: cgjoshi@aau.in.

References

- 1.Hungate R.E. Elsevier; 2013. The rumen and its microbes. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton J. Altering milk composition by feeding. J. Dairy Sci. 1989;72(10):2801–2814. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox D., Barry M., Pitt R., Roseler D., Stone W. Application of the cornell net carbohydrate and protein model for cattle consuming forages. J. Anim. Sci. 1995;73(1):267–277. doi: 10.2527/1995.731267x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handelsman J., Rondon M.R., Brady S.F., Clardy J., Goodman R.M. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chem. Biol. 1998;5(10):R245–R249. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bragg L.M., Stone G., Butler M.K., Hugenholtz P., Tyson G.W. Shining a light on dark sequencing: characterising errors in Ion Torrent PGM data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozutsumi Y., Tajima K., Takenaka A., Itabashi H. The effect of protozoa on the composition of rumen bacteria in cattle using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005;69(3):499–506. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu G.D., Lewis J.D., Hoffmann C., Chen Y.-Y., Knight R., Bittinger K. Sampling and pyrosequencing methods for characterizing bacterial communities in the human gut using 16S sequence tags. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10(1):206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass E.M., Wilkening J., Wilke A., Antonopoulos D., Meyer F. Using the metagenomics RAST server (MG-RAST) for analyzing shotgun metagenomes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010;2010(1) doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5368. (pdb. prot5368) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overbeek R., Olson R., Pusch G.D., Olsen G.J., Davis J.J., Disz T. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brulc J.M., Antonopoulos D.A., Miller M.E.B., Wilson M.K., Yannarell A.C., Dinsdale E.A. Gene-centric metagenomics of the fiber-adherent bovine rumen microbiome reveals forage specific glycoside hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106(6):1948–1953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806191105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess M., Sczyrba A., Egan R., Kim T.-W., Chokhawala H., Schroth G. Metagenomic discovery of biomass-degrading genes and genomes from cow rumen. Science. 2011;331(6016):463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1200387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.S. Gerdes,R. Overbeek, Embden-Meyerhof glycolytic pathway and Gluconeogenesis.

- 13.Lou J., Dawson K., Strobel H. Glycogen formation by the ruminal bacterium Prevotella ruminicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63(4):1483–1488. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1483-1488.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parmar N.R., Solanki J.V., Patel A.B., Shah T.M., Patel A.K., Parnerkar S. Metagenome of Mehsani buffalo rumen microbiota: an assessment of variation in feed-dependent phylogenetic and functional classification. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;24(4):249–261. doi: 10.1159/000365054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurston B., Dawson K., Strobel H. Pentose utilization by the ruminal bacterium Ruminococcus albus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60(4):1087–1092. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1087-1092.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]