Abstract

Background

This study examines the relationship of self-identified disability and oral health perception in a veteran population.

Methods

The National Survey of Veterans, 2010, data base was used to conduct a cross-sectional study of 8303 participants. Questionnaires were mailed to the veterans and the questions were developed to assess sociodemographic information, health perception and health status, among other areas of interest. The Andersen Behavioral Model was used as the framework for the study. The outcome of interest was perceived oral health and the main variable of interest was self-identified disability. The data were analyzed for descriptive, and bivariate analyses, and logistic regression.

Results

There were 1904 participants (21.2%) with self-identified disability. There were 2505 participants (41.0%) who indicated negative oral health perception. In logistic regression, individuals with self-identified disability had an unadjusted odds ratio of 1.63 (95% CI 1.44, 1.85) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.69 (95% CI: 1.44, 1.99) for negative oral health perception as compared with participants who did not self-identify disability.

Conclusion

Oral health perception in a veteran population is affected by predisposing and enabling factors among which is self-identified disability.

Keywords: oral health perception, veteran oral health, veteran disability, NSV

Introduction

A negative perception of one’s oral health has serious implications in the receipt of oral health care. Many dentists recognize the importance of social and psychological aspects in determining disease but focus on biological indices such as the decayed, missing, filled teeth index and community periodontal treatment needs index (Guerra et al., 2014). Oral health perception, or oral health quality of life, influences an individual’s overall well-being and overall quality of life (Guerra et al., 2014). Assessing oral health perception is an important step in health care practices (Campos, et al., 2014). The literature has many recent studies relating oral health perceptions and children (Gomes, et al., 2014; Mattheus, 2014; de Paula, 2014; Agostini, et al., 2014), however the literature is lacking in the implications of oral health perception and the adult veteran population.

The Department of Veteran Affairs and the Department of Defense administrators and workers are acutely aware of many of the health concerns of veterans and publish results of veteran surveys, and means to access care online to help veterans understand the protocols to secure benefits. Dental benefits (in full or in part) are available to a veteran with:

service-connected dental disabilities/conditions,

a 38 USC Ch31 status (vocational rehabilitation program),

VA care/scheduled for inpatient care and the dental condition will complicate the medical condition being treated,

homeless status and has care under VHA Directive 2007-039, or

a status of within 180 days of having served on active duty for 90 days during the Persian Gulf war era,

connected compensable dental disability from combat wounds or service trauma,

noncompensable dental conditions resulting from combat wounds or service trauma,

dental condition determined to be associated with and worsened by a service-connected medical condition,

former prisoner of war status,

100% service-connected disability/unemployable,

a 100% paid rate(U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014). Accessing the information on eligibility may be particularly difficult for veterans who are disabled. A table with the distribution of approved disability types for 2010 is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

2010 Disabled Veterans by Healthcare Priority Group

| Group 1: Veterans with service-connected disabilities at 50% or above who are unemployable due to service-connected conditions | 1,071,400 |

| Group 2: Veterans with service-connected disabilities at 30%–40% | 425,937 |

| Group 3: Veterans former Prisoners of War awarded Purple Heart discharged for disability in line of duty with service-connected disabilities at 10–20% awarded special eligibility under Tile 38 awarded medal of honor | 677,648 |

| Group 4: Veterans receiving VA aid and attendance or housebound benefits determined to be catastrophically disabled | 189,428 |

Data Source: Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Administration Office of Policy and Planning. Prepared by National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/utilization.asp

The purpose of this study is to determine if there is a relationship between self-identified disability in veterans and a negative perception of oral health. The rationale is that there may be a disparity in oral health for veterans self-identifying as disabled despite efforts to provide needed care. An adapted version of the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (Kilbourne, et al., 2007) is the basis for the study’s framework. The Anderson Behavioral Model of Health Service Use is often used in research involving health disparities and needs for people who are vulnerable (Kilbourne, et al., 2007; Andersen, 1995). Andersen (1995) suggested predisposing factors, enabling factors and need influence behavior associated with health outcomes. In this study, the predisposing factor of self-identified disability will be examined in relationship with perception of oral health. The study hypothesis is that veterans who self-identify as disabled will have different adjusted odds ratio for perceived oral health as veterans who do not self-identify as disabled. (Ho study: AOR1 = AOR2; where AOR1 is the perceived oral health adjusted odds ratio for participants who self-identify as disabled and AOR2 is the perceived oral health adjusted odds ratio for participants who do not self-identify as disabled).

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study had a cross-sectional design of secondary, public-released data collected in the National Survey of Veterans (NVS), 2010. The NVS 2010 was conducted by Westat, a contractor to the Department of Veteran Affairs, to help plan for resource allocation for Veterans (Aponte, et al., 2010). Details of the survey and its design are presented elsewhere (Aponte, et al., 2010). In summary, NVS 2010 surveys were mailed to veterans using an address-based sampling approach as there are no complete sampling frames at the Department of Veteran Affairs or the Department of Defense (Aponte, et al., 2010). The U.S. Postal Service Computerized Deliver Sequence database was used for the sampling frame for the addresses (Aponte, et al., 2010). Each veteran’s sampling weight was the product of the final screener household weight, multiple-address adjustment, and a ratio adjustment factor to control marginal totals by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and service era (Aponte, et al., 2010). There was a 66.7% NVS response rate (n=8710 veteran respondents). From that data source, participants with complete data on oral health perception and self-identification of disabilities were included (n=8393) for this study.

The study had West Virginia University Institutional Review Board acknowledgement (protocol 1412522420).

Main Outcome

The NVS oral health perception variable was developed from the question posed to the participants: “How would you rate the health of your teeth and gums? Would you say it is…” The potential responses were: “Excellent”; “Very good”; “good”; “fair”; or “poor”. In the data analysis, the participants responding “Excellent”; “Very good”; or “good” were identified as having a positive oral health perception; and the participants responding “fair”; or “poor” were identified as having a negative oral health perception.

Main variable of interest

The variable of interest for this study was self-identified disability. The variable for self-identified disability was the yes or no response to the posed question: “Have you ever applied for VA disability compensation benefits?”

Other variables

The predisposing factors that were used in this study were: sex (male v. female); age (65 years and above v. less than 65 years); race/ethnicity (Black, Other v. White); education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college/technical school v. higher education graduate and above).

Enabling factors, according to the Anderson Behavioral Model, are those which may be changeable. The enabling factors considered to be associated with perceived oral health status are: income (less than $20,000, $20000–$29999, $30000–$39999, $40000–$49999 v. $50000 and above); smoking status (current smoker, former smoker v. never smoker); marital status (no, including being widowed, divorced, separated or never married v. married, civil commitment, or civil union); internet access, at least occasionally (no v. yes); and dental visit within the previous 6 months (no v. yes).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using SAS 9.3® (Cary, NC). The a priori alpha was established as 0.05. The analyses used the survey’s sample weights provided and included a sample description, univariate Rao Scott Chi Square, and unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression of self-identified disability on the perception of oral health. The variables included in the adjusted logistic regression were sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, income, smoking status, marital status, at least occasional internet access, and having a dental visit within the previous 6 months.

Results

Sample description

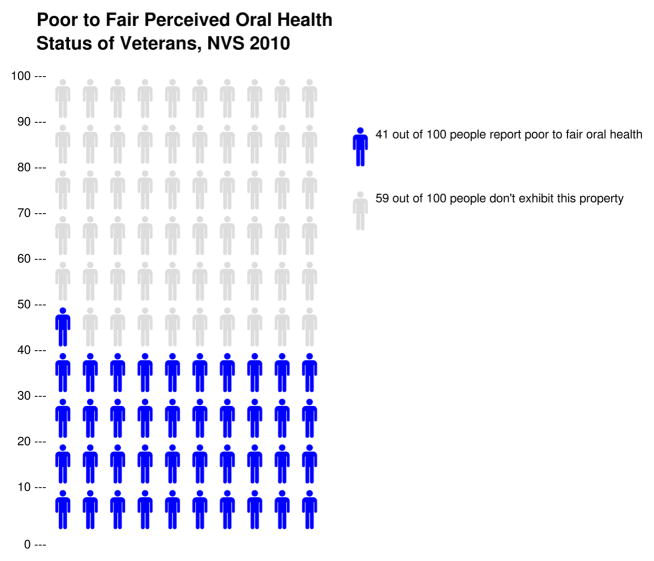

There were 91.8% of respondents who were male; 86.9% who were white; 11.3% who were black; and 40.2% who were 65 years and above. This sample’s descriptions of sex and race were similar to the overall statistics from the Department of Veteran Affairs (2014) in which 90% of veterans were male; 82.7% were white; 12.1% were black; and 44.2% were 65 years and above. There were 5.1% of participants who had less than a high school education; 25.6% who reported being a high school graduate, and 30.3% reported having some college or technical education. In terms of income, 15.0% reported an income of less than $20000, and 49.1% reported an income of $50000 or above. There were 36.3% who reported being current smokers, 44.4% who reported being former smokers, and 19.2% who reported having never smoked. There were 70.7% who were currently married or had a civil commitment or civil union. There were 73.1% who had at least occasional access to the internet. The majority (56.6%) reported a dental visit within the previous 6 months. In terms of the variables of interest, there were 21.2% of participants who reported self-identified disability. Forty-one percent of participants reported negative perceived dental status (Figure 1). This sample’s description of disability was similar to the overall statistics from the Department of Veteran Affairs (2014) in which there was 17.7% of veterans receiving disability compensation. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Figure from University of Michigan Risk Science Center, Health and Communication/ Bioethics and Social Sciences at http://www.iconarray.com/

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics, Veteran Survey, 2010 (n=8393)

| Number | Population Estimate | wt% | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 488 | 1,544,223 | 8.2 | 0.4 |

| Male | 7005 | 17,387,998 | 91.8 | 0.4 |

| Missing (900) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 7415 | 17,971,450 | 86.9 | 0.6 |

| Black | 559 | 2,338,650 | 11.3 | 0.5 |

| Other | 152 | 380,330 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Missing (267) | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18 to less than 65 years | 4374 | 8,428,695 | 59.8 | 0.6 |

| 65 years and above | 3842 | 12,531,790 | 40.2 | 0.6 |

| Missing (167) | ||||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 465 | 1,072,911 | 5.1 | 0.2 |

| High school graduate | 2093 | 5,392,500 | 25.6 | 0.6 |

| Some college/technical | 2397 | 6,374,555 | 30.3 | 0.6 |

| HE graduate & above | 3300 | 8,216,339 | 29.0 | 0.6 |

| Missing (138) | ||||

| Income | ||||

| Less than $20000 | 1048 | 3,003,193 | 15.0 | 0.5 |

| $20000–$29999 | 1007 | 2,495,908 | 12.4 | 0.4 |

| $30000–$39999 | 1079 | 2,647,536 | 13.2 | 0.4 |

| $40000–$49999 | 816 | 2,060,266 | 10.3 | 0.7 |

| $50000 and above | 3871 | 9,844,993 | 49.1 | 0.7 |

| Missing (572) | ||||

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Current smoker | 2893 | 4,093,367 | 36.3 | 0.6 |

| Former smoker | 4028 | 9,463,074 | 44.4 | 0.6 |

| Never smoker | 1427 | 7,739,913 | 19.2 | 0.6 |

| Missing (45) | ||||

| Married/Civil Commitment/Union | ||||

| Yes | 6096 | 14,892,961 | 70.7 | 0.6 |

| No | 2171 | 6,161,972 | 29.3 | 0.6 |

| Missing (126) | ||||

| Internet access, at least occasional | ||||

| Yes | 5771 | 15,341,198 | 73.1 | 0.5 |

| No | 2440 | 5,640,430 | 26.9 | 0.5 |

| Missing (182) | ||||

| Dental visit within 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 4864 | 11,928,873 | 56.6 | 0.6 |

| No | 3505 | 9,141,207 | 41.0 | 0.6 |

| Missing (24) | ||||

| Self-identified disability | ||||

| Yes | 1904 | 4,545,318 | 21.2 | 0.5 |

| No | 6489 | 16,880,877 | 78.8 | 0.5 |

| Missing (0) | ||||

| Perceived dental status | ||||

| Poor to fair | 3505 | 8,776,426 | 41.0 | 0.6 |

| Good/Very good/Excellent | 4888 | 12,649,769 | 59.0 | 0.6 |

| Missing (0) | ||||

Abbreviations: wt%: weighted column percentage; SE: standard error; HE: Higher education beyond high school graduation. “No” in Married/Civil Commitment/Union includes widowed, divorced, separated, and never married.

Bivariate and Logistic Regression results

In bivariate Rao-Scott Chi-Square analysis on perceived oral health, there were significant differences in positive and negative perceptions of oral health status in terms of sex, race, age, education, income, smoking status, marriage, at least occasional internet access, report of a dental visit within the previous 6 months, and with the key variable, self-identified disability. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Perceived oral health status with disability application and other variables: Adults 18 and above, National Survey of Veterans, 2010 (n=8393)

| Positive perception of oral health status | Negative Perception of oral health status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | wt% | SE | n | wt% | SE | p-value1 | |

| Sex | 0.0008 | ||||||

| Female | 318 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 170 | 2.7 | 0.3 | |

| Male | 3959 | 52.2 | 0.7 | 3046 | 39.6 | 0.7 | |

| Missing (900) | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | ||||||

| White | 4422 | 52.8 | 0.7 | 2993 | 34.1 | 0.6 | |

| Black | 241 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 318 | 6.0 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 86 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 66 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| Missing (267) | |||||||

| Age | 0.0024 | ||||||

| 18 to less than 65 | 2596 | 36.3 | 0.7 | 1778 | 23.4 | 0.6 | |

| 65 and above | 2206 | 22.9 | 0.5 | 1636 | 17.3 | 0.4 | |

| Missing (167) | |||||||

| Education | <.0001 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 142 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 323 | 3.5 | 0.2 | |

| High school graduate | 938 | 22.8 | 0.4 | 1155 | 13.8 | 0.4 | |

| Some college/technical | 1305 | 16.8 | 0.5 | 1092 | 13.5 | 0.4 | |

| HE graduate & above | 2436 | 29.0 | 0.6 | 3300 | 39.0 | 0.6 | |

| Missing (138) | |||||||

| Income | <.0001 | ||||||

| Less than $20000 | 346 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 702 | 9.6 | 0.4 | |

| $20000–$29999 | 461 | 5.6 | 0.3 | 546 | 6.9 | 0.3 | |

| $30000–$39999 | 545 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 534 | 6.3 | 0.3 | |

| $40000–$49999 | 468 | 6.1 | 0.3 | 348 | 4.2 | 0.3 | |

| $50000 and above | 2756 | 35.3 | 0.7 | 11’5 | 13.8 | 0.4 | |

| Missing (572) | |||||||

| Smoking Status | <.0001 | ||||||

| Current smoker | 526 | 7.4 | 0.4 | 901 | 11.8 | 0.4 | |

| Former smoker | 2295 | 25.8 | 0.5 | 1733 | 18.7 | 0.5 | |

| Never smoker | 2043 | 25.9 | 0.6 | 850 | 10.4 | 0.4 | |

| Missing (45) | |||||||

| Married/Civil Commitment/Union | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 2207 | 26.9 | 0.5 | 3798 | 43.9 | 0.6 | |

| No | 1126 | 16.4 | 0.5 | 1006 | 12.8 | 0.4 | |

| Missing (126) | |||||||

| Internet access, at least occasional | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 3740 | 47.8 | 0.7 | 2031 | 25.4 | 0.6 | |

| No | 1054 | 11.5 | 0.4 | 1386 | 15.4 | 0.4 | |

| Missing (182) | |||||||

| Dental visit within 6 months | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 3371 | 39.7 | 0.6 | 1493 | 16.9 | 0.5 | |

| No | 1443 | 19.5 | 0.6 | 1940 | 23.9 | 0.6 | |

| Missing (24) | |||||||

| Applied for disability | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 958 | 10.5 | 0.4 | 946 | 10.7 | 0.4 | |

| No | 3930 | 48.5 | 0.6 | 2559 | 30.3 | 0.6 | |

| Missing (0) | |||||||

Rao-Scott Chi-Square test p-value

Abbreviations: wt%: weighted column percentage; SE: standard error; HE: Higher education beyond high school graduation

“No” in Married/Civil Commitment/Union includes widowed, divorced, separated, and never married.

In unadjusted logistic regression on oral health perception, there was a significant relationship between self-identified disability and negative oral health perception. The odds ratio was 1.63 (95% confidence interval: 1.44, 1.85; p-value <.0001). With the predisposing factors of sex, race/ethnicity, education, and age and the enabling factors of marriage, income, smoking, at least occasional internet access, and dental visit within the previous 6 months, the adjusted logistic regression remained significant. The adjusted odds ratio was 1.69 (95% confidence interval: 1.44, 1.99; p-value <.0001). The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Logistic regression of disability application on perceived oral health status, National Survey of Veterans, 2010

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI); p-value for negative oral health perception | Adjusted OR (95%CI); p-value for negative oral health perception | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Identified Disability | ||

| Yes v. No | 1.63 (1.44, 1.85); <.0001 | 1.69 (1.44, 1.99); <.0001 |

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male v. Female | 1.32 (0.99, 1.78); 0.0617 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black v. White | 1.35 (1.02, 1.80); 0.0377 | |

| Other v. White | 1.28 (0.80, 2.05); 0.3063 | |

| Education | ||

| <HS v. HE graduate | 2.82 (2.10, 3.78); <.0001 | |

| HS graduate v. HE graduate | 1.82 (1.53, 2.18); <.0001 | |

| <HE graduate v. HE graduate | 1.60 (1.36, 1.88); <.0001 | |

| Age | ||

| 65 years and above v. 18 to less than 65 | 1.05 (0.92, 1.21); 0.4594 | |

| Enabling factors | ||

| Married | ||

| No v. yes | 0.91 (0.77, 1.07); 0.2353 | |

| Internet access, at least occasional | ||

| No v. yes | 1.39 (1.19, 1.63); <.0001 | |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20000 v. $50000 and above | 2.20 (1.71, 2.84); <.0001 | |

| $20000–$29999 v. $50000 and above | 1.84 (1.49, 2.27); <.0001 | |

| $30000–$39999 v. $50000 and above | 1.55 (1.27, 1.88); <.0001 | |

| $40000–$49999 v. $50000 and above | 1.35 (1.09, 1.67); 0.0067 | |

| Smoking | ||

| Current v. never smoker | 2.51 (2.04, 3.07); <.0001 | |

| Former smoker v. never smoker | 1.56 (1.35, 1.80); <.0001 | |

| Dental visit within the previous 6 months | ||

| No v. yes | 1.85 (1.62, 2.12); <.0001 | |

Abbreviations: OR= Odds ratio; AOR= Adjusted odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; <HS= less than high school graduate; HS= high school; <HE= some higher education beyond high school, but less than graduating; and HE= higher education beyond high school. “No” in Married/Civil Commitment/Union includes widowed, divorced, separated, and never married.

Discussion

This study of U.S. veterans indicated a significant relationship of self-identified disability on negative oral health perception. The adjusted odds ratio for negative oral health perception (either fair or poor oral health) was 1.69 in veterans reporting self-identified disability as compared with veterans not reporting self-identified disability. The veterans reporting a negative oral health perception were 41% of the participants in the study. The predisposing factors (male sex, black race/ethnicity, and less education) were associated with negative oral health perception. The lack of enabling factors (lower income, smoking, no dental visit within the previous 6 months, and lack of internet access) were associated with negative oral health perception.

The literature is lacking in studies in which researchers have examined self-identified disability and oral health perception. Searches in Google Scholar and PubMed on the key words, “Veteran Affairs dental” and “oral health disabled veterans,” have had limited relevant results. Therefore, making study comparisons is difficult. However, in a study including dependent living geriatric veterans (n=132) (corresponding with this study’s self-identified disability) and oral/dental health (corresponding with this study’s oral health perception), there was a similar relationship of independent living and better oral health (Loesche, et al., 1995). Researchers of a study of 538 male patient users of the Department of Veteran Affairs services showed an association of self-perceived oral health and more medical problems (Jones, et al., 2001). The studies differed in the measures of self-perceived oral health; and, the condition of having more medical problems is not equivalent to self-identified disability.

This study’s findings were dissimilar to a study in which mental and physical summary scores of the Short Form-36 (corresponding with this study’s self-identified disability) were not related oral health quality of life (corresponding with this study’s oral health perception). In the former study, researchers of male veteran medical outpatient recipients (n=2425) were surveyed (Jones, et al., 2006). The majority (60%) of the patients indicated good, very good, or excellent oral health. The study differed from the current study in that, in the former, researchers used recipients of medical outpatient services, and limited their study to males. They used a different approach with an instrument that covered more domains (Jones, et al., 2004).

Researchers using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2004) data of non-institutionalized U.S. residents found 35.5% of Hispanics, 36.8% of Non-Hispanic Blacks, and 21.4% of Non-Hispanic Whites who reported poor oral health (Wu, et al., 2011). Researchers in another study using the same NHANES data found increases in severity of oral health problems with trends toward disabilities in instrumental activities of daily living (adjusted odds ratio, 1.58), leisure and social activities (adjusted odds ratio, 1.70), lower extremity mobility (adjusted odds ratio, 1.31), and general physical activities (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63) (Yu, et al., 2011). Their results considered the oral health status outcomes of periodontal disease and edentulism. And in a study of women using National Health Interview Survey data (1994–1995), the researchers found that women with 3 or more functional limitations were more likely to report being unable to get dental care (Chevarley, et al., 2006).

In studies of war veterans in other countries, researchers reported greater prevalence of temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and muscle pain (masseter, temporal, pterygoid, digastric and sternocleidomastoid) in Isfahan veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder than in other groups (Mottaghi & Zamani, 2014); poorer oral hygiene, periodontal status, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and muscle pain in Croatian war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder than in age matched men (Muhvic-Urek, et al., 2007); and poor oral health, higher number of periodontal pockets, and differences in brushing and dental visits in Croatian soldiers than in peacetime groups (Surman, et al., 2008).

This study has several strengths. It uses a large, national data base with a stringent sampling design which makes it representative of the veteran population. The data are current. And the response rate was good (66.7%). The weaknesses of the study involve the self-reported nature of the questionnaire. It is possible that social desirability bias may have resulted in an under-representation of “yes” responses to the question about disability, and an over-representation of positive oral health perception. However, such responses would have weakened an even stronger association if they are present.

The public health implications of this research include the recognition that disability has an impact on multiple domains of life, including perceived oral health status. Veterans with disabilities are members of a vulnerable population and there is a need to improve the oral health status through improving the access to care, improving clinical education and skills in working with disabled veterans, monitoring services, and improving policies for increased access to care. Future research is needed in determining the knowledge and skills of dentists in working with disabled veterans, and interventions with disabled veterans to access oral health care.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM104942.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Agostini BA, Machry RV, Teixeira CR, Piovesan C, Oliveira MD, Bresolin CR, Ardenghi TM. Self-perceived oral health influences tooth brushing in preschool children. Braz Dent J. 2014;25:248–52. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201302426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte M, Giambo P, Helmick J, Hintze W, Sigman R, Winglee M, Dean D, Rajapaksa S, Ragan M, Shumway C, Manglitz C. Westat. Rockville, MD: 2010. National Survey of Veterans, Active Duty Service Members, Demobilized National Guard and Reserve Members, Family Members, and Surviving Spouses. Task 101-G87089. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JA, Carrascosa AC, Zucoloto ML, Maroco J. Validation of a measuring instrument for the perception of oral health in women. Braz Oral Res. 2014;28 doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2014.vol28.0033. pii: S1806-83242014000100244. Epub 2014 Aug 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevarley FM, Thierry JM, Gill CJ, Ryerson AB, Nosek MA. Health, Preventive Health Care, and Health Care Access Among Women With Disabilities in the 1994–1995 National Health Interview Survey, Supplement on Disability. Women’s Health Issues. 2006;16:297–312. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula JS, Ambrosano GM, Mialhe FL. Oral Disorders, Socioenvironmental Factors and Subjective Perception Impact on Children’s School Performance. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2014 doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veteran Affairs. Department of Veteran Affairs Statistics at a Glance. 2014 http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Quick_Facts.asp.

- Gomes MC, Pinto-Sarmento TC, Costa EM, Martins CC, Granville-Garcia AF, Paiva SM. Impact of oral health conditions on the quality of life of preschool children and their families: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra MJ, Greco RM, Leite IC, Ferreira EF, Paula MV. Impact of oral health conditions on the quality of life of workers. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:4777–86. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320141912.21352013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Kressin NR, Spiro A, Randall CW, Miller DR, Hayes C, Kazis L, Garcia RI. Self-reported and clinical oral health in users of VA health care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M55–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.1.m55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Kressin NR, Miller DR, Orner MB, Garcia RI, Spiro A. Comparison of patient-based oral health outcome measures. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13:975–985. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000025596.05281.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Kressin NR, Kazis LE, Miller DR, Spiro AS, Lee A, Garcia RI. Oral conditions and quality of life. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:167–181. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Horvitz-Lennon M, Post EP, McCarthy JF, Cruz M, Welsh D, Blow FC. Oral Health in Veterans Affairs Patients Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2007;67:42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche WJ, Abrams J, Terpenning MS, Bretz WA, Dominguez L, Grossman NS, Hildebrandt GH, Langmore SE, Lopatin DE. Dental findings in geriatric populations with diverse medical backgrounds. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattheus DJ. Efficacy of oral health promotion in primary care practice during early childhood: creating positive changes in parent’s oral health beliefs and behaviors. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13:316–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaghi A, Zamani E. Temporomandibular joint health status in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2014;3:60. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.134765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhvic-Urek M, Uhac I, Vuksic-Mihaljevic Z, Leovic D, Blecic N. Oral health status in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2007;34:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suman M, Spalj S, Plancak D, Dukic W, Juric H. The influence of war on the oral health of professional soldiers. Int Dent J. 2008;58:71–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dental Benefits for Veterans. 2014 IB 10-442. http://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/resources/publications/hbco/hbco_faq.asp.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Administration Office of Policy and Planning. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; http://www.va.gov/vetdata/utilization.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Plassman BL, Liang J, Remle RC, Bai L, Crout RJ. Differences in Self-Reported Oral Health Among Community-Dwelling Black, Hispanic, and White Elders. J Aging Health. 2011;23:267–288. doi: 10.1177/0898264310382135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Lai Y, Cheung WS, Kuo H. Oral Health Status and Self-Reported Functional Dependence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. JAGS. 2011;59:519–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]