Abstract

Reminiscing has been shown to be a critical conversational context for the development of autobiographical memory, self-concept, and emotional regulation (for a review, see Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006). Although much past research has examined reminiscing between mothers and their preschool children, very little attention has been given to family narrative interaction with older children. In the present study, we examined family reminiscing in spontaneous narratives that emerged during family dinnertime conversations. The results revealed that mothers contributed more to the narratives than did fathers in that they provided, confirmed, and negated more information, although fathers requested more information than mothers. In exploratory analyses, mothers’ contributions to shared family narratives were found to be related to fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors in their children, while fathers’ contributions to individual narratives of day-today experiences were related to fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors in their children. These results indicate that mothers and fathers may play different roles in narrative construction with their children, and there is some suggestion that these differences may also be related to children’s behavioral adjustment.

Throughout the day, we experience mundane, important, and emotional events. Some of these events are experienced with our families while others are experienced independent of them, but at the end of the day we share these stories with our family. Over the past two decades, a growing body of research has revealed differences in the ways that parents reminisce about past events with their children. Specifically, whereas some parents are more elaborative and scaffold their child’s recall with the use of questions, prompts, and cues, other parents tend to be more repetitive and repeatedly ask for the same information (for a review, see Fivush, 2007; Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006). However, the scope of these studies has been rather narrow. Most studies have examined elicited narratives between mothers and their preschool children about shared experiences, with limited research extending parent-child reminiscing to middle childhood. Only a few studies have looked at both mothers and fathers, and even fewer have moved away from an elicited narrative paradigm in order to capture more naturalistic family narrative interactions (for some exceptions, see Mullen & Yi, 1995; Peterson & McCabe, 1992). How families spontaneously reminisce about the past is an important question because more elaborative maternal reminiscing is related to children’s developing autobiographical memory skills, self-concept, and emotional regulation (for a review, see Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006). Therefore, the major objective of this study is to examine differences in spontaneous family narrative interaction. A more exploratory secondary objective was to examine relations between family reminiscing and child emotional and behavioral adjustment.

Parental Reminiscing Style

The majority of research on parent-child reminiscing about past events has focused on dyadic interactions between a mother and her child. This research has demonstrated that mothers vary along a dimension of elaboration, with more elaborative mothers asking for and providing more information and confirming and evaluating their children’s participation to a greater extent than less elaborative mothers. Maternal elaborative reminiscing style is consistent over time, across siblings, and is specific to the reminiscing context; that is, mothers who are more elaborative when reminiscing are not necessarily more conversationally elaborative in other conversational contexts (for a review, see Fivush et al., 2006). There is more limited research examining father-child reminiscing that demonstrates that fathers also vary along a dimension of elaboration, although mothers are generally more elaborative, especially about emotional aspects of the past, than are fathers (Adams, Kuebli, Boyle, & Fivush, 1995; Fivush, Brotman, Buckner, & Goodman, 2000; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1993).

Elaboration is a global construct that captures parental guidance, or scaffolding (Fivush et al., 2006). This scaffolding can take various forms, including providing rich detailed information for the child, requesting information from the child, confirming information that the child provides in the service of eliciting and validating the child’s participation, and negating information that can lead to the negotiation of shared meaning. There is some evidence that provision of information is more beneficial earlier in the preschool years but that as children develop more sophisticated memory and language skills, requesting information may be more advantageous (Farrant & Reese, 2000; Haden, Ornstein, Rudek, & Cameron, 2009). In fact, Haden, Ornstein, Rudek, and Cameron (2009) have recently demonstrated that mothers who request and confirm more information from their preschool children facilitate the development of autobiographical memory skills more so than mothers who simply provide information.

Family Narratives

To date, little reminiscing research has examined the family as a whole. Emerging from a family systems perspective, examining how the family as a whole communicates, interacts, and responds to one another is essential for understanding families and the factors that contribute to the well-being of the individual members (Kreppner, 2002). Studies examining family patterns of communication more generally have revealed that open and supportive communication styles, in contrast to more controlling and unsupportive communication, foster rich affective relationships between parents and children, which contribute to more positive views of the self (Openshaw, Thomas, & Rollins, 1984; Ryan, 1993), higher self-esteem (Blake & Slate, 1993; Enger, Howerton, & Cobbs, 1994; Kernis, Brown, & Brody, 2000), and a higher sense of self-efficacy in children (for a review, see Carton & Nowicki, 1994). In addition, family interactions that facilitate autonomy while not sacrificing relatedness facilitate positive and healthy self-esteem development in children (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Conner, 1994).

Focusing specifically on family narrative interaction may be particularly important because in talking about the past, family members reconstruct their personal and shared experiences and in this process reinterpret and reevaluate what happened and what it meant. As Ochs, Taylor, Rudolph, and Smith (1992) have argued, family narratives are critical sites for socialization because complex discussions arise when family members experienced an event together and subsequently reminisce about it. Through participating in this type of family reminiscing, children learn how to become not only storytellers but also theory builders. In order for a family to construct a coherent narrative together, each part of the story must be explained, and the members of the family may challenge what was told, may add in different pieces, or may critique and rework the current theory of what happened.

Family Narratives and Child Well-being

Co-construction of family narratives allows for the creation of shared meaning and a shared history, which may be critical for children’s emotional understanding and well-being (Fiese & Sameroff, 1999). Research with mothers and their preschool children has revealed that there are clear relations between reminiscing about past events and children’s developing emotional understanding and adjustment. In general, mothers who reminisce about the past in more elaborative ways, providing rich detail and confirming and eliciting their children’s participation, have children who show higher levels of emotional understanding and regulation. Studies have confirmed that maternal elaboration is the critical dimension in predicting child outcome (for reviews, see Fivush, 2007; Fivush et al., 2006).

For example, Laible (2004a, 2004b) found that mothers who were more elaborative when reminiscing about past behavioral transgressions had pre-school children who showed more advanced emotional and moral understanding as well as more adaptive emotional regulation. In research with somewhat older children, Fivush and Sales (2006; Sales & Fivush, 2005) found that mothers who provided more emotional and explanatory language when reminiscing about parent-child conflicts had 8- to 12-year-old children with better coping skills and better emotional well-being. Critically, research has also shown that mother-child talk about the past is more predictive of children’s social-emotional well-being, understanding, and regulation than is talk in other contexts, including ongoing conflicts and book reading (Laible, 2004a, 2004b; Reese, Bird, & Tripp, 2007), suggesting that narrative reminiscing may provide a unique context for emotional socialization. Thus, it is clear that elaborative reminiscing has positive benefits.

We have recently extended the research on dyadic reminiscing and well-being to examine relations between elicited family narratives and child well-being. In this research, we asked 40 middle-class two-parent families with a preadolescent child to reminisce about a shared negative experience and a shared positive experience. In a first analysis, examining the overall family narrative style, Bohanek, Marin, Fivush, and Duke (2006) identified three narrative interaction styles that were differentially related to children’s well-being. Conversations with a coordinated perspective incorporated and integrated information from all members and were related to higher self-esteem, especially in girls. Conversations with an individual perspective, in which family members took turns telling their thoughts and feelings about the event without integration among the perspectives, were associated with a more external locus of control, especially in boys. Conversations with an imposed perspective, in which one family member was in charge of the conversation or that included unpleasant exchanges between members, were not associated with either self-esteem or locus of control (although this was likely because of the low incidence of this style in this sample). Marin, Bohanek, and Fivush (2008) subsequently examined the emotional and explanatory language in these elicited narratives in more detail and found that families who expressed and explained specific negative emotions when conarrating shared negative experiences had children who rated themselves higher on social, behavioral, and academic competence. Furthermore, Bohanek, Marin, and Fivush (2008) found that it was specifically mothers’ use of emotional expressions and explanations that was, in general, related to higher self-esteem and behavioral adjustment in their children, whereas fathers’ use of emotional expressions and explanations, in general, was not. These findings establish that the ways in which families reminisce about past events is important for child well-being and that mothers and fathers play different roles. However, these studies did not examine how spontaneous narratives emerge in everyday family interaction and whether these interactions may be related to child adjustment.

Dinnertime Narratives

In this study, we undertook a more systematic investigation of how narratives emerge in spontaneous family interactions. We chose to tape record typical dinnertime conversations because this is a time when the family comes together to share their day. Thus, it seems an ideal context for the telling of stories. Although there have been many previous studies that have examined family talk around the dinner table, this research has focused mainly on socialization of language and politeness routines (for summaries, see Pan, Perlmann, & Snow, 2000; Blum-Kulka, 1997; for qualitative research on family dinnertime narratives, see Ochs & Capps, 2001). There is also a vast literature detailing the positive effects of family rituals more generally (e.g., Sameroff & Fiese, 1999; Sprunger, Boyce, & Gaines, 1985; Wamboldt & Reiss, 1989) and also the positive effects of family mealtimes on children’s well-being (CASA, 2003; Hofferth and Sandberg, 2001a, 2001b). This research has only examined the number of meals that families share and has not examined the interaction around the dinner table; however, researchers have argued that the beneficial effects of family dinnertime could be because parents and children are able to discuss what happened during the day (Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001b). Based on the research reviewed here on the beneficial effects of elaborated reminiscing, we argue that the narratives told around the dinner table may be an important part of what makes dinnertime beneficial for children. We focused on how mothers and fathers scaffolded these narratives in terms of providing, requesting, confirming, and negating information.

Previous qualitative research on family dinnertime narratives confirms that families share stories of their own individual experiences (especially events of the day) as well as narratives of experiences shared by multiple family members around the dinner table (Ochs & Capps, 2001; Ochs et al., 1992). Only three studies have quantitatively examined narrative differences for events that were shared between the mother and child and those that were only experienced by the child, but intriguing differences have been found. For example, Reese and Brown (2000) found that when a mother and child were reminiscing about a shared past event, the mother’s provision of information was related to how much her child contributed to the conversation. However, when a child was recounting an individual experience, the mother’s elaborative questions were related to how much her child contributed. Interestingly, children reported more information overall when recounting individual events than when they were reminiscing with their mother (for similar findings, see also McCabe & Peterson, 1991; Menig-Peterson, 1975). Thus, it is possible that narratives of events experienced by individual members of a family may differ in important ways from narratives of events that were shared by two or more family members. In the dinnertime context we were able to examine how different types of family narratives, shared and unshared as well as recent and remote, are told. A secondary objective of this research was to examine possible relations between family narratives and child well-being. In initial work addressing this question, Fiese and her colleagues (Fiese & Marjinsky, 1999; Fiese & Sameroff, 1999) examined several sets of family narratives that emerged during dinnertime conversations to determine what, if any, narrative components were consistent and important across many types of family stories. Interestingly, they found that parents’ appropriate modulation of affect was an important mediator of fewer child behavior problems. However, the researchers did not fully examine the types of narratives that emerged over the dinner table or the process of narrative interaction as each family member contributed to the evolving story.

Our goal in this study was to systematically describe the frequency, type, and process of family narrative interaction. We predicted, based on the limited research examining mother-preschooler and father-preschooler dyads, that mothers would be more elaborative overall than fathers. A secondary and more exploratory goal was to examine possible relations between family narratives and child well-being; we predicted that parents who demonstrated a more elaborative style, through providing, requesting, and confirming more information, might have children who displayed higher levels of emotional and behavioral adjustment as measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991).

Method

Participants

As part of a larger project examining relations between family communication, family narratives, and family well-being, 40 middle-class two-parent families with at least 1 child between 9 and 12 years old (the focal child) were recruited from various sources (e.g., newspaper ads, sports camps). Thirty-seven of these families participated in the dinnertime portion of the project that is reported here. We note that these are the same families for which we examined elicited narratives as described in the introduction. Thirty of these families are dual earners, and 7 are single earners. This is a highly educated sample, with 17 mothers and 22 fathers having completed a postgraduate degree, 13 mothers and 8 fathers having completed college, 7 mothers and 6 fathers having some college education, and 1 father who completed some high school. Twenty-eight families self-identified as Caucasian, 3 as African American, 5 as mixed race, and 1 as Asian American. Thirty of the families are traditional nuclear families, 5 are blended families, and 2 are extended families with at least 1 additional adult living with them. The number of children in each family ranged from 1 to 6 (mean number of children is 2.7), with an age range of 2 months to 23 years. Three families had 1 child present at the meal, 22 families had 2 children present, 8 families had 3 children present, 3 families had 4 children present, and 1 family had 5 children present. Families were informed that we were interested in family patterns of interaction during routine family events. No mention was made of specific interest in talk about past events or narratives. All parents signed informed consent, and adolescents gave verbal assent to the procedures as approved by the institutional review board. Families were paid $25, and children were given movie tickets.

Families were given a tape recorder and asked to record two to three family dinnertime conversations over a two-week period. Thirty-one families returned at least two conversations, and six families returned just one dinner conversation.1 If two conversations were available, the second one was used in analyses because we assumed that the family would be less self-conscious during a second taping; for the remaining 6 families, their single recorded dinnertime conversation was used. All conversations were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy before coding. Dinner conversations varied in length from 20 to 45 minutes.

In addition to collecting the audiotaped dinnertime conversations, mothers and fathers were also asked to complete the CBCL on the focal child.

Child Behavior Checklist

The CBCL (Achenbach, 1991) was chosen to assess child behaviors because it is widely used in the clinical and developmental literatures to determine the presence or absence of internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalizing (e.g., acting out) problems in children. Because only the internalizing and externalizing scales are of interest in the present study, we only discuss items and scoring for these scales. Internalizing and externalizing scores are calculated independently, with the responses from 32 items summed to create a total internalizing score and the responses from 33 items summed to create a total externalizing score. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, with 0 indicating that the item is “not true” of the child, whereas a 2 indicates that the item is “very true or often true” of the child. For example, sample items reflective of internalizing problems include “Feels worthless or inferior” and “Would rather be alone than with others,” and sample items reflective of externalizing problems include “Gets in many fights” and “Swearing or obscene language.” Lower scores on either scale indicate less frequent internalizing or externalizing behaviors, and higher scores indicate more frequent or severe internalizing or externalizing behaviors. In the present study, both mothers and fathers completed the CBCL for the target child. However, past research has indicated that multiple informants often contribute different reports of child behavior (e.g., Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987) and that mothers may be perceived as more accurate than other informants (Phares, 1997). With one exception, the mothers in the present 37 families were the primary caretakers of the children, and thus we present data only from the maternal ratings. We do note that in preliminary analyses of our data the paternal CBCL ratings were not related to any narrative measures (these analyses are available from the first author). We return to this issue in the discussion.

As a measure of internal consistency, Achenbach (1991) calculated Cronbach’s alphas for each scale with the internalizing scale α = .90 and the externalizing scale α = .93, which indicates strong internal consistency. Alphas on a subset of this sample were reported by Bohanek et al. (2008) and were α = .86 and α = .91, respectively. As reported by Achenbach, overall one-week test-retest reliability Pearson rs for the internalizing and externalizing scores are .89 and .93, respectively.

Transcription and Coding

Two coders read through all of the transcripts together and identified all the narratives within the dinnertime conversations. A narrative was defined as a reference to a specific past event. Narratives began when the past event was introduced and ended when the narrative talk changed (i.e., to present or future tense events). Although there was often nonnarrative talk embedded within the narrative (e.g., “Pass the salt”), this talk was omitted from quantitative analyses.

Once all the narratives were identified, coding focused on two issues: (1) descriptions of the narratives and (2) family members’ narrative interaction. Descriptions focused on who and what the narratives were about and when the narrated event occurred. Narrative interaction focused on the kinds of narrative utterances used by mothers, fathers, and children in the narratives, specifically whether participants were requesting, providing, confirming, or negating information. More specifically, narrative description focused on:

Theme, or what the narrative was about (e.g., academics, social activities, family vacations).

Time of occurrence, or when the event within the narrative took place. Recent events happened either that day or the day before, and remote events took place more than two days earlier (although virtually all of the remote events in the corpus occurred at least several months in the past).

Type of narrative, or whether the past event being described was experienced by just one person at the table (independent), or by more than one family member (family). Note that independent narratives experienced by one family member can include people outside the family as participants, and thus the event is experienced independent of the family. Therefore, independent narratives focus on a family member as an individual, whereas family narratives focus on individuals as members of the family.

Initiator, or who begins the narrative, coded as the mother, father, or child. Narratives can be initiated either by a question (e.g., “What did you do in school today?”) or by an introduction of an event (“I sat next to Sally at lunch today”).

Subject of the narrative, or who the narrative is about. This could either be the mother, father, a child, or the family (defined as two or more family members). It is important to note that this is different than narrative type in that an event might have been shared by several family members (e.g., the christening of one of the children) and thus considered a family narrative, but the subject of the narrative would be the child who was being christened.

Length, assessed as the number of words contributed to the narrative by each family member.

Coding narrative interaction focused on the process of conarrating the event and was adapted from previous schemes developed to code for elaborative reminiscing (e.g., Fivush & Fromhoff, 1988; Haden, 1998). First, each utterance within each narrative was identified. An utterance was defined as any proposition with either an explicit or implied subject and verb as well as affective exclamations and confirmations or negations of previous utterances. Each utterance was then coded into one of the following mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories:

Request. Information is asked for in the form of who, what, when, where, why, and how questions (e.g., “How was your day today?”; “Why did you do that?”).

Provide. Information that has not been given before is presented (e.g., “I had a water fight in school today”; “This is not cool”).

Confirm. Provision of information is validated or repeated (e.g., “That was exciting.” “It was.”); where any “yes” or variation thereof (such as “Yeah,” “Okay,” “Uh huh”) follows a request for or provision of information (e.g., “Did you do that?” “Yes.”).

Negate. Any “no” or variation thereof (such as “Uh uh”) follows a request for, or provision of, information (e.g., “Did you do that?” “No.”). It is important to note that these negations often occurred in the context of negotiating the facts of what happened and were typically not argumentative in nature (e.g., family members did not typically negate others’ emotions, thoughts, or feelings).

Two coders independently coded 15% of all the narratives and achieved 86% agreement across narrative coding categories, with a range of 75–100% and a kappa of .82. The remaining narratives were divided between the two coders and were coded independently.

Results

Presentation of the results is divided into three major sections. We first present a description of the narratives in terms of theme and narrative type. Because the number of children present at the dinner table varied from family to family and in order to control for skew in the distribution, we coded families as having 1 or 2 children present at the table versus families with 3 or more children present. The number of children present at the dinner table was then used as a covariate in all analyses. For the most part, the number of children present was not significantly related to any of the variables of interest and is therefore only reported when significant. We then turn to a more fine-grained analysis of the narrative interaction, focusing on the utterances that mothers, fathers, and children contribute to the narratives. Because our main focus is on the number and type of narratives that families co-construct and the process of co-construction as a function of family member, we base all of our analyses on frequency. As we and others have argued, although proportionalizing these kinds of data may correct for a general level of talkativeness, frequency is the correct metric to use because an essential aspect of reminiscing style is the extent to which families engage in this kind of talk. Furthermore, frequency, and not proportion, has been shown to be critical for child outcome (Farrant & Reese, 2000; Fivush, 1998; Fivush et al., in press; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1993; Wang, 2001; Wang, 2006). All significant (p < .05) main effects and interactions were followed up with t-tests.

In the third section, we examine exploratory relations between the dinnertime narratives and maternal ratings of children’s well-being. Because of the exploratory nature of the analyses and the relatively small sample size for these correlational analyses, we have chosen to focus on the effect size of the Pearson correlations between parental reminiscing and child emotional and behavioral adjustment rather than on traditional p values (for discussions of this issue, see Kline, 2004; Vacha-Haase et al., 2000; and Vacha-Haase & Thompson, 2004). Traditionally, small effect sizes are those around .10 while moderate effect sizes are those around .30 (Aron & Aron, 1999; Cohen, 1992), and we have chosen to highlight both small effect sizes (r ≥ .31) as well as moderate effect sizes (r ≥ .55). However, we note here and discuss further below that these are exploratory analyses, and in choosing to focus on effect sizes we are including correlations at the marginally significant/trend level; we are cautious to note this where appropriate and interpret the data accordingly.

Across the 37 families, 235 narratives were identified. Of these, 226 could be classified by when they occurred and who was present during the event. Thus, all analyses are based on these 226 narratives. Before we proceed to more specific analyses, it is worth emphasizing that this is a large number of narratives, a mean of 6.35 per family, told around the dinner table. Given the duration of most of these dinnertime interactions, this averages out to approximately 1 narrative of a past event emerging every 5 minutes during an average family dinnertime.

Description of the Narratives

Narrative theme

Inspection of the narratives indicated nine broad themes that captured the types of events narrated, as shown in Table 1 (for a qualitative description of a portion of these dinnertime narratives, see Fivush, Bohanek, & Duke, 2008). The majority of narratives were about the children’s day or the parent’s day and reflected routine, everyday events in which family members engaged. Children’s day was further divided into school events that were academic in nature (tests, grades, classes), school events that were social in nature (recess, talking with friends between classes), and non-school-related activities (after-school sports, playing with friends). Parent’s day was divided into work events that were work-related (meetings, tasks at work), work events that were social in nature (lunch with co-workers, talking with colleagues), and non-work-related activities (running errands, talking to or having dinner with friends). As can be seen in Table 1, both parents and children talk the most about their non-school-and non-work-related activities.

Table 1.

Narrative Themes

| Narrative Themes | Number of Narratives |

|---|---|

| Children’s day | |

| School day—academics | 25 |

| School day—social | 22 |

| Nonschool activities | 48 |

| Parent’s day | |

| Workday—work issues | 7 |

| Workday—social | 3 |

| Nonwork activities | 30 |

| Parent-child social interactions | 20 |

| Family knowledge, stories, history | 17 |

| Food | 16 |

| Animals | 12 |

| Injuries, illnesses, doctor visits | 9 |

| Vacations | 9 |

| Outside/other | 8 |

| Total | 226 |

The next most frequent narrative theme is parent-child social interactions, which includes shopping, errand running, and sports where at least one child and one parent are present. Family knowledge, stories, and history are just that, a collection of narratives about the general workings/ routines within the family; family stories with the parents, children, or all members; and family history, which includes stories about when the parents were children, when the parents were married but before they had children, and when the children were little.

There were also narratives about food, most often reviewing what everyone had for lunch earlier that day or what family members had eaten and enjoyed in the past. Animal narratives included stories about current pets, past pets, and wild animals. Narratives about injuries, illnesses, and doctor visits are self-explanatory and ranged in severity from making an appointment to see a doctor to a slight scratch to a possible cyst in a child’s knee. Stories about vacations were also told, some about the whole family and others that only the children or only the parents had enjoyed. Finally, there were eight narratives that were about people outside the family, such as a friend’s illness and a friend’s ski trip.

Narrative time, type, and initiation

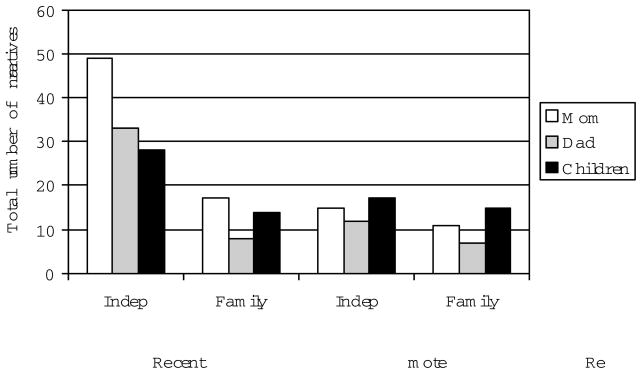

Consideration of the narratives further suggests that narratives varied by when the event being recounted occurred (recent or remote) and whether the narratives were about an event that occurred to a family member independent from the rest of the family (independent) or whether it was an event shared by at least two members of the family (family). In addition, narratives could be initiated by the mother, the father, or a child. Figure 1 shows the total number of narratives by time and type as well as who initiated each of these types of narratives.

Figure 1.

Total Number of Narratives Told at the Dinner Table by Time, Narrative Type, and Initiator.

A 2 (time) × 2 (type) × 3 (initiator) Repeated Measures ANOVA confirmed that there were more recent narratives (M = 4.02, SD = 2.74) than remote narratives (M = 2.08, SD = 1.69; F[1,35] = 5.51, p < .05) and more independent narratives (M = 4.16, SD = 2.92) than family narratives (M = 1.95, SD = 1.41; F[1, 35] = 9.46, p < .01). More specifically, a significant interaction between time and type (F[1, 35] = 4.86, p < .05) further revealed that there were more recent independent narratives (M = 2.97, SD = 2.72) than remote independent narratives (M = 1.19, SD = 1.41; t[1, 36] = 3.38, p < .01), recent family narratives (M = 1.05, SD = 1.25; t[1, 36] = 3.62, p < .01), and remote family narratives (M = .89, SD = .99; t[1, 36] = 4.30, p < .01), which did not differ from each other. Although there appear to be differences in who was initiating narratives in Figure 1, in fact there was no significant main effect or interactions with initiator. This is likely due to the large standard deviations for the mean number of initiations for family members.

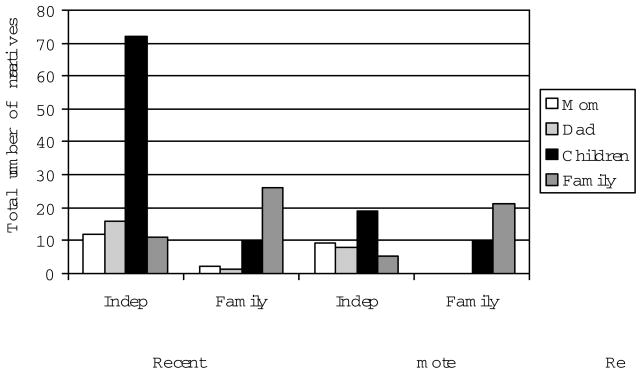

A further question concerned who the narratives were about. That is, regardless of who initiated the narratives, the subject of the narratives could be the mother, the father, a child, or the family, as displayed in Figure 2 by time and subject of the narrative. Of the 226 narratives, 8 were about people outside of the immediate family and were thus excluded from this analysis. A 2 (time) × 2 (type) × 4 (subject) Repeated Measures ANOVA revealed no differences in who these narratives were about; regardless of time and type, there were no significant differences in whether families told narratives about either parent, a child, or the family. Although Figure 2 gives the impression that there are more narratives about children than mothers or fathers (particularly for recent independent narratives), this effect is not significant when controlling for the number of children present at the table.

Figure 2.

Total Number of Narratives about Each Family Member by Time and Narrative Type.

Narrative length

The next set of analyses addressed the amount of family members’ contributions to the dinnertime narratives. It is important to emphasize that most of the dinnertime narratives were extended discussions about the event, with multiple family members participating. Across families, recent independent narratives are on average 102.70 words long (SD = 71.69), recent family narratives are 133.28 words long (SD = 384.40), remote independent narratives are 84.26 words long (SD = 118.53), and remote family narratives are on average 70.04 words long (SD = 79.74).

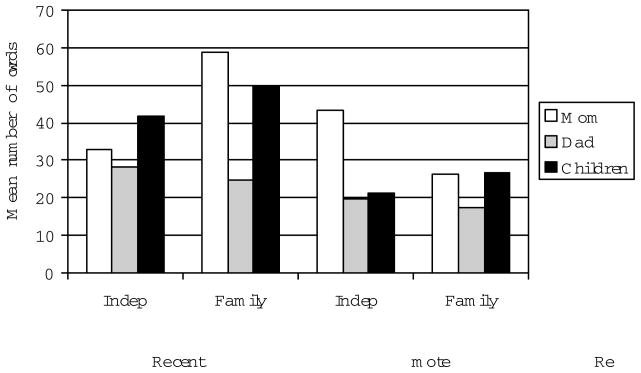

The mean number of words contributed to each narrative type by mothers, fathers, and children was calculated for recent and remote and for independent and family narratives, as displayed in Figure 3. A 2 (time) × 2 (type) × 3 (speaker) Repeated Measures ANOVA revealed that mothers (mean overall number of words = 161.21, SD = 208.70; t[1, 36] = 2.65, p < .05) and children (mean overall number of words = 139.53, SD = 170.27; t[1.36] = –2.19, p < .05) contributed more words across all narratives than did fathers (mean overall number of words = 89.54, SD = 110.24; F[2, 34] = 3.18, p < .05), but mothers and children did not differ from each other. In addition, the number of children present influenced family members’ contributions to the conversations (F[2, 34] = 5.04, p =.01) such that fathers with 1 or 2 children talked more (mean overall number of words = 111.53, SD = 125.20) than fathers with 3 or more children (mean overall number of words = 43.73, SD = 46.75; t[1, 34] = 2.38, p < .05), but mothers and children did not differ in how much they talked as a function of how many children were at the table. Moreover, there were no differences in how much family members talked as a function of when the event occurred or the type of the narrative. Thus overall, although there were more recent independent narratives told than any other type, once a narrative was initiated, families contributed to each of these narratives types about equally. However, mothers and children contributed substantially more to narrative telling than did fathers.

Figure 3.

Mean Number of Words per Family Member by Time and Narrative Type.

Overall, families told many narratives around the dinner table, with most of these narratives focused on the children’s and parent’s social relationships and interactions. Most narratives were about events that occurred that day, but a surprisingly large number of narratives were about events experienced in the remote past. Intriguingly, mothers, fathers, and children initiated about the same number of narratives, and these narratives were just as likely to be about the mother or father as about one of the children. However, mothers and children, regardless of the number of children in the family, contributed more to these narratives than did fathers.

Narrative Interaction

The second set of analyses focused on the narrative interaction, defined as requesting, providing, confirming, and negating information. For some analyses, several Mauchly’s tests indicated that the sphericity assumption had been violated. Therefore, in these analyses, degrees of freedom have been corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser Epsilon.

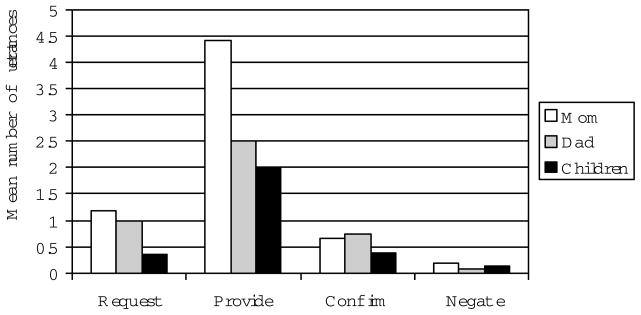

An initial 3 (family member: mother, father, children) × 4 (narrative type: recent independent, remote independent, recent family, remote family) × 4 (utterance type: request, provide, confirm, negate) Repeated Measures ANOVA was conducted. There was a main effect of family member (F[2, 72] = 11.96, p < .01), a main effect of utterance type (F[3, 37, corrected] = 24.94, p < .01), and a family member by utterance type interaction (F[6, 62, corrected] = 6.82, p < .01). There was no main effect of event type nor did event type enter into any significant interactions, indicating that narrative interaction was similar across all four event types. The mean number of each utterance type by family member across event types is displayed in Figure 4. In order to explore the family member by utterance type interaction, separate ANOVAs on each utterance type were performed and were followed up with t-tests (p < .05) where appropriate.

Figure 4.

Mean Number of Function Utterances by Family Member.

A main effect of family member for requests (F[2, 51, corrected] = 6.88, p < .01) revealed that mothers (M = 1.18, SD = 0.87) requested significantly more information than did children (M = 0.35, SD = 0.34; t[1, 36] = 5.78, p < 0.01), as did fathers (M = 0.99, SD = 1.69; t[1, 36] = 2.49, p < 0.05), but mothers and fathers did not differ from each other (see Figure 4). For providing information, a main effect (F[2, 51, corrected] = 9.08, p < .01) showed that mothers (M = 4.43, SD = 5.44) provided significantly more information than either fathers (M = 2.50, SD = 3.62; t[1, 36] = 2.67, p < 0.05) or children (M = 1.99, SD = 2.60; t[1, 36] = 3.71, p < 0.01), but fathers and children did not differ from each other. For confirmations, a trend (F[2, 45, corrected] = 2.65, p = .10) suggested that mothers and fathers were similar (Ms = 0.66 and 0.74, respectively, SDs = 0.55 and 1.42, respectively), but both confirmed more than children (M = 0.38, SD = 0.70; t[1, 36] = 2.40, p < 0.05 for mothers; t[1, 36] = 2.53, p < 0.05 for fathers). Finally, for negations, a main effect (F[2, 72] = 3.58, p < .05) revealed that mothers (M = 0.19, SD = 0.24) negated significantly more often than did fathers (M = 0.07, SD = 0.16; t[1, 36] = 2.52, p < 0.05), but mothers and children (M = 0.14, SD = 0.19) did not differ from each other, nor did fathers and children.

In summary, comparisons between mothers and fathers indicated that mothers provided and negated more information than did fathers, but mothers and fathers requested and confirmed information at similar levels. Mothers also provided, requested, and confirmed more information than children, but mothers and children negated information equally often. Fathers also requested and confirmed more information than did children, but fathers and children provided and negated information equally often.

Relations between Narratives and Child Well-being

The last set of analyses focused on relations between family narrative interaction within each of the event types and children’s well-being as measured by the CBCL. As discussed previously, because of the exploratory nature of these analyses, both significant correlations (p < .05) as well as correlations above the traditional level of significance at respectable effect sizes are highlighted in Table 2. As can be seen, although there were no distinct relations between narrative interaction and child well-being within the recent family and remote independent narratives, patterns of clustered relations emerged, particularly within the remote family narratives and to a lesser extent within the recent independent narratives. Specifically, within the remote family narratives, mothers who confirmed, negated, and, to a lesser extent, provided more information had children with fewer internalizing problems. Also within the remote family narratives, children who requested more information had fewer internalizing problems, and children who negated more information had fewer internalizing problems and, to a lesser extent, fewer externalizing problems. Within the recent independent narratives, correlations of small effect sizes indicated that fathers who requested more information had children with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems.

Table 2.

Correlations between Utterance Type (by Family Member) and Child Well-being

| Recent Independent | Recent Family | Remote Independent | Remote Family | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | |

| Mother | ||||||||

| Request | −.19 | .05 | −.24 | −.18 | .04 | −.14 | −.21 | −.27* |

| Provide | .04 | −.19 | .15 | −.13 | −.25 | −.24 | −.31* | −.16 |

| Confirm | −.26 | −.16 | .11 | .05 | −.22 | −.04 | −.34** | −.15 |

| Negate | −.21 | −.22 | −.18 | −.14 | −.24 | −.33** | −.33** | −.13 |

| Father | ||||||||

| Request | −.32* | −.31* | .14 | −.08 | −.07 | −.09 | −.12 | .16 |

| Provide | −.21 | −.16 | .19 | −.06 | .01 | −.01 | −.20 | −.18 |

| Confirm | −.07 | −.27* | .21 | −.08 | −.01 | −.11 | −.07 | −.17 |

| Negate | −.07 | .00 | −.22 | −.02 | .13 | −.04 | .04 | −.20 |

| Children | ||||||||

| Request | −.22 | .08 | .01 | .02 | −.08 | .03 | −.34** | −.08 |

| Provide | −.26 | −.21 | .18 | −.05 | .08 | −.04 | −.21 | −.04 |

| Confirm | −.26 | −.15 | .15 | −.11 | .06 | −.06 | −.23 | −.07 |

| Negate | −.35** | −.10 | .18 | −.04 | .04 | −.01 | −.41** | −.32* |

p < .10,

p < .05.

Discussion

In this study we examined spontaneous family narrative interactions around the dinner table. Clearly, stories about one’s day and one’s past emerge frequently in typical family interactions, about once every five minutes, and when past events do emerge as topics of conversation, these narratives are extended and collaborative, with multiple family members contributing to the evolving story. Not surprisingly, most of the narratives were individual family member’s stories of their day, but a substantial number of narratives focused on remote events experienced both by the family as a whole and by individual members. Interestingly, these remote narratives were as long, as elaborated, and as collaborative as narratives of the day’s events, indicating that multiple types of family narratives are an integral aspect of daily family interaction. Our results shed light on how family narrative interactions are structured and also, in exploratory analyses, how they may be related to child well-being.

In terms of what kinds of stories are told, we were somewhat surprised to discover that the majority of narratives focused on children’s and parents’ social activities outside of school or work, as opposed to more academic- and career-related topics. This is particularly interesting, as past research has shown family dinnertime to be a significant predictor of child well-being and academic performance (CASA, 2003; Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001a, 2001b). Yet discussions about exams and homework are clearly not the only important issues for children. It appears that discussing and resolving events that are more social in nature may also be critical to children’s success in school, perhaps by helping children resolve these stressors and thus allowing them to focus more on learning and less on nonschool activities and social concerns when they are in the classroom. We are not arguing that talk about academic work is not important but rather that it does not seem to occur around the dinner table. Most likely this kind of talk occurs in other contexts, such as doing homework. At the dinner table, where the focus is on the social activities of both children and parents, children may be learning from their parents to negotiate smooth social interactions and to take the perspective of other people as they discuss their social lives.

Moreover, in contrast to previous descriptions of family dinnertime conversations that found that the vast majority of talk focused on the child (Perlman, 1984), we found that narratives around the dinner table were just as likely to be about the parents as about the children. Because the children in the present study were older than the preschool children studied in most previous research, it is important to note that the focus of these family narratives may have different socialization goals, such as fostering a more explicit understanding of self and others and building both individual and family histories. Thus, parents do not focus as extensively on their children’s individual experiences but instead also include many narratives about their own experiences as well as shared family experiences. This is important, because children are being exposed to and are presumably integrating stories about themselves, about who their parents are outside of the home, and about who their family is as a collective unit. In this way, children are learning to take the perspectives of others and to build theories about the social world (Ochs et al., 1992).

Furthermore, although the majority of narratives are about the events of individual family member’s days, about a quarter of narratives focused on events that individual family members or the family as a whole had experienced in the remote past. Somewhat surprisingly, there were no differences on any measure among these different types of events in who initiated or who participated or how elaborated these narratives were. Clearly, family members are engaged in creating the stories of their lives across time. However, mothers and fathers seem to play somewhat different roles in this process. Once a narrative is introduced, mothers and fathers are equally likely to request and confirm information about the event. However, mothers provide and negate more information than do fathers. Previous research has indicated that mothers are more elaborative than fathers when reminiscing individually with their preschool children about shared events (Adams et al., 1995; Fivush et al., 2000; Reese et al., 1993). In our study, we found that when the family is interacting as a whole, both mothers and fathers are involved in soliciting their children to tell the story, but mothers provide and negate more information than fathers, suggesting that mothers play a larger role than fathers in facilitating an elaborated, co-constructed narrative in which each family member contributes and negotiates information.

That mothers are more involved in co-constructing family narratives relates to previous research that has found that mothers are the largest contributors to dinnertime conversations in general (e.g., Ochs & Taylor, 1992; Perlmann, 1984) and also relates to research demonstrating that mothers are more involved in kin-keeping activities, including keeping family histories and stories (McDaniel, 1998; Rosenthal, 1985; Sherman, 1990; Wamboldt & Reiss, 1989). Our findings confirm and extend these findings by pointing to the process by which mothers and fathers differentially contribute to the co-construction of family narratives. Importantly, our results also suggest that children are actively engaged in narrative interaction. Although they seem to rely on their parents to scaffold the narratives through requesting and confirming information, children provide as much information as do fathers and negate as much information as do mothers. Moreover, this pattern holds even for family narratives about events in which the children themselves did not participate or were too young to remember, such as parents’ childhood events and children’s births and baptisms. That children are so engaged even in these narratives further suggests that these narratives provide a basis for establishing critical family history that serves to create and maintain emotional and identity bonds across time (Fivush, Bohanek, & Duke, 2008; Pratt & Fiese, 2004).

This is particularly interesting in light of our exploratory analyses that revealed differential relations between maternal and paternal narrative contributions and child well-being. Specifically, mothers who frequently provide, confirm, and negate information within the remote family narratives have children with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems. As just mentioned, mothers often assume the role of kin keeper in the family (McDaniel, 1998; Rosenthal, 1985; Sherman, 1990; Wamboldt & Reiss, 1989), and it appears that as mothers create, elicit, and negotiate these remote family narratives around the dinner table, this may be related to positive aspects of children’s well-being, perhaps because they are building a shared history through time that provides a sense of identity and continuity for the child (Fivush et al., in press; Pratt & Fiese, 2004). Children’s roles in these narrative interactions are also related to well-being. Within the remote family narratives, children’s own requests for more information and their negations were associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, suggesting that children who are more actively engaged in creating a shared family history show higher levels of well-being.

In contrast, there is some suggestion that fathers who request information within the recent independent narratives have children with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems. Fathers may play more of a role in day-to-day problem solving, helping their children to create coherent accounts of the day’s events that facilitate a sense of mastery over one’s life. Certainly, theory suggests that mothers and fathers differentially contribute to their children’s developing self-understanding and well-being, with mothers focusing on emotional and relational issues and fathers focusing on achievement and problem solving (for a discussion of these issues, see Bohanek, Marin, & Fivush, 2008); these results extend these arguments to suggest that mothers and fathers may play different roles in helping their children understand the events of their lives, both remote and recent, in ways that allow children to create coherence and mastery over their experiences.

As already discussed, these analyses examining relations among maternal, paternal, and child contributions to the family dinnertime narratives and child well-being are exploratory in nature and should be interpreted as such. Our sample size is relatively small for these types of analyses, with ratings of child behavior from only 37 families collected at the same time point as the narratives. Interestingly, there were virtually no relations between narrative participation and paternal ratings of child behavior. There are several explanations for these null effects, including that whereas all of these were two-parent families, in all but one family the mother was the primary caretaker of the children. Thus, the mothers’ ratings may provide more information about the child’s typical behaviors than the fathers’ ratings because she may be most familiar with their emotional and behavioral adjustment, although we do acknowledge that there may be other factors influencing these relations. However, the suggestive results revealed between maternal ratings of child behavior and narrative participation raise an interesting issue of bidirectionality in our data. It is possible that the ways in which parents and children discuss the events of their lives influences child emotional and behavioral adjustment, but it is also possible that children who exhibit certain types of behaviors and responses elicit certain narrative interactions from their parents. Future research examining longitudinal relations between narrative interaction and child well-being, beginning very early in development, is needed to determine the direction of these effects. This longitudinal data is also critical for determining whether there are some developmental periods during which narrative interaction may be more closely related to child behavior, as it is possible that more relations between narrative interaction at the dinner table and children’s well-being may be found earlier in development, when children may spend more time with their families and direct familial influences may be stronger.

While our findings add to the existing literature on family reminiscing and child well-being in important ways, we must acknowledge several limitations to the study. First, although our sample is somewhat racially and ethnically diverse, all of the families were middle class, and the majority of the children were well adjusted. Future studies examining family narratives should include larger samples in order to examine greater variability among families, especially among families and children who may be at risk. Second, we only report data from one time point, which does not allow us to draw conclusions about causality. Furthermore, it is of course possible that the family narrative interaction styles captured here may be reflective of broader overall family communication patterns. However, recent research suggests that reminiscing may be a distinctive context that is uniquely predictive of child outcome (see Laible, 2004b; Reese, Bird, & Trip, 2007). Reminiscing provides a context within which family members are able to share, evaluate, and interpret experiences in a situation that is personally meaningful and reflective, and thus it may be critical in developmental outcomes (for an extended argument, see Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006). Finally, the need to compare different types of narrative talk about the past as well as nonnarrative talk within the same families is critical for understanding the context of narrative development. Future analyses on this data set will allow us to compare and contrast patterns of talk within the elicited family narratives, the spontaneous narrative talk around the dinner table, and the nonnarrative talk also found within the dinnertime conversations along the same dimensions, thus providing important information regarding how children come to represent, interpret, and share the events of their lives and how the development of a narrative style differs from the development of a more general style of communication.

In summary, this investigation of family narrative interaction has demonstrated the frequency and the importance of this kind of talk. Parents, and especially mothers, of school-age children initiate and engage their children in telling the events of their day. But importantly, parents also discuss their own recent experiences, and the family as a whole reconstructs their shared experiences of both the recent and remote past, indicating that the co-construction of family dinnertime narratives serves as much a familial bonding function as an individuation function. Through telling and sharing the stories of our lives with our families, we learn both who we are as individuals and, perhaps even more importantly, who we are as members of a family group that gives our lives both a historical and an emotional center and defines who we are as individuals in the present.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation supporting the Emory Center for Myth and Ritual in American Life. We would like to thank Rachel Robertson, Justin Rowe, and Stacy Zolondek for help in data collection.

Footnotes

The families who returned a single dinnertime conversation did not differ from the families who returned two dinnertime conversations on any of the narrative variables (e.g., number of narratives per family, number of words, function categories, etc.) more often than would be expected by chance.

Contributor Information

Jennifer G. Bohanek, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Robyn Fivush, Emory University.

Widaad Zaman, Emory University.

Caitlin E. Lepore, Emory University

Shela Merchant, Emory University.

Marshall P. Duke, Emory University

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams L, Kuebli J, Boyle P, Fivush R. Gender differences in parent-child conversations about past emotions: A longitudinal investigation. Sex Roles. 1995;33:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, O’Connor TG. Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem. Child Development. 1994;65:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Aron E. Statistics for psychology. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blake PC, Slate JR. Parental verbal communication: Impact on adolescent self-esteem. National Association for School Psychologists Communique. 1993;22:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Blum-Kulka S. Dinner talk: Cultural patterns of sociability and socialization in family discourse. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Marin KA, Fivush R. Family narratives, self, and gender in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Marin KA, Fivush R, Duke MP. Family narrative interaction and children’s sense of self. Family Process. 2006;45:39–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carton JS, Nowicki S., Jr Antecedents of individual differences in locus of control of reinforcement: A critical review. Genetic, Social, & General Psychology Monographs. 1994;120:31–81. [Google Scholar]

- CASA [National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University] Family day: A day to eat dinner with your children. 2003 Retrieved October 4, 2003, from http://casafamilyday.org/familyday/

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enger JM, Howerton DL, Cobbs CR. Internal/external locus of control, self-esteem, and parental verbal interaction of at-risk black male adolescents. Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;134:269–274. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1994.9711730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant K, Reese E. Maternal style and children’s participation in reminiscing: Stepping stones in children’s autobiographical memory development. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2000;1:193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Marjinsky K. Dinnertime stories: Connecting family practices with relationship beliefs and child adjustment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64:52–68. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese B, Sameroff A. The family narrative consortium: A multidimensional approach to narratives. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64(2 Pt 1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R. The stories we tell: How language shapes autobiography. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1998;12:483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R. Maternal reminiscing style and children’s developing understanding of self and emotion. Clinical Social Work. 2007;36:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Bohanek JG, Duke MP. The self in time: Subjective perspective and intergenerational history. In: Sani F, editor. Continuity and self. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman M, Buckner J, Goodman S. Gender differences in parent-child emotion narratives. Sex Roles. 2000;42:233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Fromhoff FA. Style and structure in mother-child conversations about the past. Discourse Processes. 1988;11:337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Haden CA, Reese E. Elaborating on elaborations: Role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development. 2006;77:1568–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Marin K, McWilliams K, Bohanek JG. Family reminiscing style: Parent gender and emotional focus in relation to child well-being. Journal of Cognition and Development. doi: 10.1080/15248370903155866. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Sales JM. Coping, attachment, and mother-child reminiscing about stressful events. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Haden CA. Reminiscing with different children: Relating maternal stylistic consistency and sibling similarity in talk about the past. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:99–114. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden CA, Ornstein PA, Rudek DJ, Cameron D. Reminiscing in the early years: Patterns of maternal elaborativeness and children’s remembering. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Sandberg JF. How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001a;63:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Sandberg JF. Children at the millennium: Where have we come from, where are we going? In: Owens T, Hofferth S, editors. Advances in Life Course Research Series. New York: Elsevier Science; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Brown AC, Brody GH. Fragile self-esteem in children and its associations with perceived patterns of parent-child communication. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:225–252. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Beyond significance testing: Reforming data analysis methods in behavioral research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner K. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families as systems. In: McHale JP, Grolnick WS, editors. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 225–257. [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Mother-child discourse in two contexts: Links with child temperament, attachment security, and socioemotional competence. Developmental Psychology. 2004a;40:979–992. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Mother-child discourse about a child’s past behavior at 30 months and early socioemotional development at age 3. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004b;50:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Marin KA, Bohanek JG, Fivush R. Positive effects of talking about the negative: Family narratives of negative experiences and preadolescents’ perceived competence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:573–593. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe A, Peterson C. Getting the story: A longitudinal study of parental styles in eliciting narratives and developing narrative skill. In: McCabe A, Peterson C, editors. Developing narrative structure. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 217–252. [Google Scholar]

- Menig-Peterson C. The modification of communicative behavior in pre-school-aged children as a function of the listener’s perspective. Child Development. 1975;46:1015–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen M, Yi S. The cultural context of talk about the past: Implications for the development of autobiographical memory. Cognitive Development. 1995;10:407–419. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SG. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Arizona State University; 1998. It’s Bedlam in this house! Investigating subjective experiences of family communication during holiday celebrations. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E, Capps L. Living narrative: Creating lives in everyday storytelling. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E, Taylor C. Family narrative as political activity. Discourse and Society. 1992;3:301–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E, Taylor C, Rudolph D, Smith R. Storytelling as a theory-building activity. Discourse Processes. 1992;15:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenshaw DK, Thomas DL, Rollins BC. Parental influences of adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1984;4:259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pan BA, Perlmann RY, Snow CE. Food for thought: Dinner table as a context for observing parent-child discourse. In: Menn L, Bernstein Ratner N, editors. Methods for studying language production. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmann RY. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Boston University; 1984. Variations in socialization styles: Family talk at the dinner table. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, McCabe A. Parental styles of narrative elicitation: Effect on children’s narrative structure and content. First Language. 1992;12:299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. Accuracy of informants: Do parents think that mother knows best? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:165–171. doi: 10.1023/a:1025787613984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MW, Fiese BE. Family stories and the lifecourse: Across time and generations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Bird A, Tripp G. Children’s self-esteem and moral self: Links to parent-child conversations. Social Development. 2007;16:460–478. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Brown N. Reminiscing and recounting in the preschool years. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2000;14:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Haden CA, Fivush R. Mother-child conversations about the past: Relationships of style and memory over time. Cognitive Development. 1993;8:403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal CJ. Kinkeeping in the familial division of labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1985;47:965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM. Control and information in the interpersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;43:450–461. [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Fivush R. Social and emotional functions of mother-child reminiscing about stressful events. Social Cognition. 2005;23:70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Fiese BH. Narrative connection in the family context: Summary and conclusions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64:105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman MH. Family narratives: Internal representations of family relationships and affective themes. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sprunger LW, Boyce WT, Gaines JA. Family-infant congruence: Routines and rhythmicity in family adaptations to a young infant. Child Development. 1985;56:564–572. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase T, Nilsson JE, Reetz DR, Lance TS, Thompson B. Reporting practices and APA editorial policies regarding statistical significance and effect size. Theory & Psychology. 2000;10:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase T, Thompson B. How to estimate and interpret various effect sizes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, Reiss D. Defining a family heritage and new relationship identity: Two central tasks in the making of a marriage. Family Process. 1989;28:317–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1989.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Did you have fun? American and Chinese mother-child conversations about shared emotional experiences. Cognitive Development. 2001;16:693–715. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Relations of maternal style and child self-concept to autobiographical memories in Chinese, Chinese immigrant, and European American 3-year-olds. Child Development. 2006;77:1794–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]