ABSTRACT

Flaviviruses are significant human pathogens that have an enormous impact on the global health burden. Currently, there are very few vaccines against or therapeutic treatments for flaviviruses, and our understanding of how these viruses cause disease is limited. Evidence suggests that the capsid proteins of flaviviruses play critical nonstructural roles during infection, and therefore, elucidating how these viral proteins affect cellular signaling pathways could lead to novel targets for antiviral therapy. We used affinity purification to identify host cell proteins that interact with the capsid proteins of West Nile and dengue viruses. One of the cellular proteins that formed a stable complex with flavivirus capsid proteins is the peroxisome biogenesis factor Pex19. Intriguingly, flavivirus infection resulted in a significant loss of peroxisomes, an effect that may be due in part to capsid expression. We posited that capsid protein-mediated sequestration and/or degradation of Pex19 results in loss of peroxisomes, a situation that could result in reduced early antiviral signaling. In support of this hypothesis, we observed that induction of the lambda interferon mRNA in response to a viral RNA mimic was reduced by more than 80%. Together, our findings indicate that inhibition of peroxisome biogenesis may be a novel mechanism by which flaviviruses evade the innate immune system during early stages of infection.

IMPORTANCE RNA viruses infect hundreds of millions of people each year, causing significant morbidity and mortality. Chief among these pathogens are the flaviviruses, which include dengue virus and West Nile virus. Despite their medical importance, there are very few prophylactic or therapeutic treatments for these viruses. Moreover, the manner in which they subvert the innate immune response in order to establish infection in mammalian cells is not well understood. Recently, peroxisomes were reported to function in early antiviral signaling, but very little is known regarding if or how pathogenic viruses affect these organelles. We report for the first time that flavivirus infection results in significant loss of peroxisomes in mammalian cells, which may indicate that targeting of peroxisomes is a key strategy used by viruses to subvert early antiviral defenses.

INTRODUCTION

Flaviviruses are arthropod-transmitted pathogens that infect hundreds of millions of people each year. Dengue virus (DENV) is the etiological agent of the most common mosquito-borne disease in the world, dengue fever (reviewed in reference 1). The related flavivirus West Nile virus (WNV) is the most important vector-transmitted pathogen in North America. Despite their medical significance, there are no DENV/WNV-specific vaccines or antiviral therapies that are approved for use in humans. Understanding how these viruses take advantage of and manipulate host cells may provide the foundation for therapies that target virus-host interactions.

Recent studies identified flavivirus capsid proteins as critical components of the virus-host interface. They are the first viral proteins made in flavivirus-infected cells, but their role in virus assembly is not required until after genome replication has taken place. As such, from a temporal perspective, capsid proteins are well positioned to modulate the host cell environment during the infection cycle. For example, we have shown that the WNV capsid protein inhibits apoptosis via a mechanism requiring phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity (2). The capsid protein of the most intensely studied flavivirus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), has been shown to interact with at least 28 different human proteins, many with known roles in apoptotic pathways (reviewed in reference 3). Whether the HCV capsid, also known as core protein, functions to induce or inhibit apoptosis is still a matter of debate. However, through its interaction with host cell proteins, the HCV capsid protein plays significant roles in the pathogenesis of viral hepatitis by affecting lipid metabolism and promoting steatosis (4). In parallel, virus replication and/or assembly may benefit through capsid interaction with host proteins that function in transcription, innate immunity, and RNA metabolism.

Evidence suggests that interactions between other flavivirus capsids and host cell proteins are also important for virus replication and/or assembly of infectious virions. For example, the nucleolar helicase DDX56 interacts with WNV capsid in a postreplication process that is required for the infectivity of virions (5, 6). To further investigate the roles WNV and DENV capsid proteins play in virus-host interactions, we used affinity purification and mass spectrometry to identify capsid-binding proteins. Based on the conserved nature of flavivirus replication strategies, we expected to identify a number of common host proteins that interact with capsid proteins. One of the host cell proteins that bound both WNV and DENV capsid proteins is the peroxisome biogenesis regulator Pex19 (7). Until recently, very little was known regarding if or how peroxisomes function in controlling or facilitating replication of viruses in mammalian cells. However, a number of recent studies suggest that peroxisomes orchestrate early antiviral signaling (8, 9). In keeping with an antiviral role for peroxisomes, it was recently reported that agonists, such as fenofibrate and related compounds, that activate the transcriptional regulator, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, inhibit replication of some viruses (10, 11). In the present study, we show that flavivirus infection significantly reduces the numbers of peroxisomes, likely as a mechanism to thwart early antiviral signaling that emanates from these organelles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus infection.

A549 and HEK293T cells from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin, 1 mM HEPES (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The WNV strain NY99 and DENV type 2 (DENV-2) were kindly provided by Mike Drebot at the National Microbiology Laboratory (Winnipeg, Canada). WNV and DENV manipulations were performed in containment level 3 (CL-3) and CL-2 facilities, respectively.

Antibodies.

Human anti-DENV-2 serum was provided by Robert Anderson (Dalhousie University). Production of polyclonal antibodies to the amino-terminal 20 amino acid residues of DENV-2 capsid protein in guinea pigs was contracted to Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory (Canadensis, PA). Guinea pig and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to WNV capsid protein and goat anti-p32 were generated in our laboratory (2, 12, 13). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to the tripeptide Ser-Lys-Leu (SKL) were produced as described previously (14). Rabbit antibodies against FLAG epitope (Sigma), GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (Abcam), and Pex19 (Epitomic and Abcam) and mouse monoclonal antibodies to GAPDH (Proteintech), Hsp60 (BD Sciences), p32/gC1q-R (Babco, Richmond, CA, and our laboratory [13]), Lamp1 (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology), PMP70 (Sigma), and WNV NS3/2b (R&D Systems) were purchased from the indicated suppliers.

Plasmids and transfection.

DENV-2 and WNV capsid cDNAs, generated by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1, were subcloned into the indicated expression vectors. The PCR products encoding DENV and WNV capsids were cloned into the HindIII and BamHI sites of the triple-FLAG-tag vector pCMV3F-C (15) for overexpression, affinity purification, and mass spectrometry studies. Nontagged versions of the capsid cDNAs were used for localization studies. A549 cells were used for intracellular-localization studies and, unless otherwise indicated, HEK293T cells for affinity purification or coimmunoprecipitation assays. The A549 and HEK293T cells were transfected with the appropriate expression plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and PerFectin (Genlantis), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|

| CMV3FC-DENV Cap-For | 5′-GAATTCATGAATGACCAACGGAAAAAG-3′ |

| mChDENV Cap-Rev | 5′-GGATCCTCTGCGTCTCCTATTCAAGATG-3′ |

| CMV3FC-WNV Cap-For | 5′-GAATTCATGTCTAAGAAACCAGGAGGGC-3′ |

| mChWNV Cap-Rev | 5′-GGATCCTCTTTTCTTTTGTTTTGA-3′ |

Restriction endonuclease recognition sites are in boldface.

The small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used to knock down expression of Pex19 proteins are shown in Table 2 and were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, IA). A549 cells were transfected with the siRNAs (20 nM) using RNAiMax transfection reagent (Invitrogen).

TABLE 2.

siRNAs for Pex19 knockdown

| siRNA | Strand | siRNA sequence |

|---|---|---|

| siControl | Antisense | 5′-AUACGCGUAUUAUACGCGAUUAACGAC-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-CGUUAAUCGCGUAUAAUACGCGUAT-3′ | |

| siPEX19 no. 1 | Antisense | 5′-GGGUUCUUCCUCAGCCAACUCCUUCAU-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-GAAGGAGUUGGCUGAGGAAGAACCC-3′ | |

| siPEX19 no. 2 | Antisense | 5′-GUCAGCUCUUCUUCCGACAUGCUGGAG-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-CCAGCAUGUCGGAAGAAGAGCUGAC-3′ |

Proteomics experiments.

HEK293T cells at 70% confluence in five 100-mm dishes were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged protein. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were lysed using two different methods. In method 1, cells were resuspended in 2.5 pellet volumes of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and P8340 protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich]) and then subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing. The extracts were clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatants were added to 50-μl bed volumes of anti-FLAG M2 resin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 4 h of mixing at 4°C, the resin was washed twice in lysis buffer and then twice with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 125 mM KCl, pH 8.0.

In method 2 (described in references 16 and 17), cells were resuspended in 1.33 pellet volumes of TpA (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and P8340), followed by 10 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. One pellet volume of TpB (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 1.26 M potassium acetate, and 75% glycerol) was added to the lysate, followed by 10 additional strokes in the homogenizer. The extracts were clarified by centrifugation and then dialyzed against 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.1 M potassium acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol. After dialysis, the extract was added to a 50-μl bed volume of anti-FLAG M2 resin and mixed for 4 h at 4°C. The resin was washed twice in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton, 10% glycerol and then twice in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 125 mM KCl, pH 8.

In both methods, complexes were eluted from the anti-FLAG resin with three successive 150-μl additions of 0.5 M ammonium hydroxide (pH 11 or higher). The eluates were pooled and lyophilized, followed by one wash in double-distilled H2O (ddH2O), and the recovered proteins were trypsinized as described by Chen and Gingras (18). The peptides were analyzed by affinity chromatography coupled to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) on a ThermoElecron LCQ DecaXP mass spectrometer coupled with an Agilent capillary HPLC 1100 series at the Advanced Protein Technology Centre (Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada).

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

HEK293T cells (1.2 × 106), seeded the day before into P100 dishes, were infected with DENV or WNV or transfected with appropriate expression plasmids. At designated time points posttransfection or postinfection, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before lysing with NP-40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM dithiothreitol) containing Complete protease inhibitors (Roche) on ice for 30 min. The lysates were clarified at 14,000 rpm for 20 min in a microcentrifuge at 4°C and precleared with protein G or protein A Sepharose beads for 5 min at 4°C, followed by incubation with appropriate antibodies for several hours at 4°C. Except when anti-FLAG antibodies were employed, immune complexes were recovered using Dynabeads coated with protein A or protein G (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4°C. Anti-FLAG immune complexes were recovered using anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma). Bound immune complexes were washed several times with NP-40 lysis buffer before elution by boiling in protein sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for immunoblotting, as described previously (2).

Confocal and superresolution microscopy.

A549 cells on coverslips were processed for confocal or superresolution microscopy by fixing for 30 min at room temperature with paraformaldehyde (3% in PBS) or 1.5% electron microscopy (EM) grade paraformaldehyde, respectively, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, and 300 mM sucrose in PBS (Sigma). Samples were then quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, washed three times in PBS, permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.5% in PBS) for 5 min, and then washed again with PBS. Incubations with primary antibodies diluted (1:1,000 to 1:4,000) in blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin [BSA] and PBS) were carried out at room temperature for 1 h, followed by three washes in PBS containing 0.1% BSA. Samples were then incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking buffer for 40 min at room temperature, followed by three washes in PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse/rabbit, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-guinea pig, Alexa Fluor 546 donkey anti-mouse/rabbit, Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-guinea pig, Alex Fluor donkey anti-rabbit, and Alexa Fluor 647 goat-anti mouse (Invitrogen).

Prior to mounting, samples were incubated with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (5 μg/ml) for 5 min at room temperature before washing in PBS containing 0.1% BSA. Coverslips were mounted on microscope slides using Fluoro-Gel mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Services, Hatfield, PA). Confocal mages were acquired using an Olympus IX-81 spinning-disk confocal microscope equipped with a 60×/1.42-numerical-aperture (NA) oil PlanApo N objective.

For superresolution microscopy, coverslips were mounted on slides that had been precleaned with acetone and ethanol using SlowFade Gold reagent mounting medium (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a DeltaVision OMX V4 structured illumination microscope (Applied Precision, GE) equipped with a 60×/1.42-NA oil PSF (PlanApo N) objective and immersion oil (refractive index of 1.514 to 1.516). Images were analyzed using Volocity 6.2.1 software (PerkinElmer).

Quantification of peroxisome numbers and sizes.

Z stack images (2 μm thick) acquired using an Olympus 1 by 81 spinning-disk confocal microscope equipped with a 60×/1.42 oil PlanApo N objective were exported from Volocity 6.2.1 as an OEM.tiff file. The exported images were then processed using Imaris 7.2.3 software (Bitplane). Peroxisomes within polygonal areas that excluded the nucleus were quantified (quality and voxels). Within the selected regions, the absolute intensity and region volume of the peroxisomes were determined and then entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The data were then analyzed using Student t tests.

Where indicated, 0.125-μm optical sections acquired using an Applied Precision OMX superresolution microscope (with a 60×/1.42 oil lens and three complementary metal oxide semiconductor [CMOS] cameras) were also analyzed. The raw data were processed using Deltavision OMX SI image reconstruction and registration software, and the final images were imported into Volocity 6.2.1 software as .dv files for quantification. In each cell, peroxisomes were selected based on the absolute pixel intensity in the corresponding channel, and their numbers and volumes were then determined. Only the SKL-positive structures with volumes between 0.001 and 0.05 μm3 were included for measurement. Histograms of the peroxisome size distribution were generated using Microsoft Excel.

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA from infected or capsid-expressing cells was purified using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNAs were reverse transcribed using random primers (Invitrogen) and SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase II (Invitrogen) at 42°C for 1.5 h. The resulting cDNAs were mixed with the appropriate primers (IDT) and the PerfeCTa SYBR green SuperMix with Low ROX (Quanta Biosciences) and amplified for 40 cycles (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 30 s at 68°C) in a Stratagene Mx3005P quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR machine. The gene targets and primers used are listed in Table 3. The ΔCT values were calculated using β-actin mRNA as the internal control. The ΔΔCT values were determined using noninduced samples as the reference value. Relative levels of lambda interferon (IFN-λ) and irf1 mRNAs were calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCT.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides primers for qRT-PCR

| Target gene | Primer orientation | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Forward | 5′-CCTGGCACCCAGCACAAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACT-3′ | |

| IFN-λ1 | Forward | 5′-CGCCTTGGAAGAGTCACTCA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAAGCCTCAGGTCCCAATTC-3′ | |

| IFN-λ2 | Forward | 5′-AGTTCCGGGCCTGTATCCAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAACCGGTACAGCCAATGGT-3′ | |

| IFN-λ3 | Forward | 5′-TAAGAGGGCCAAAGATGCCTT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTGGTCCAAGACATCCCCC-3′ |

RESULTS

WNV and DENV capsid proteins bind Pex19.

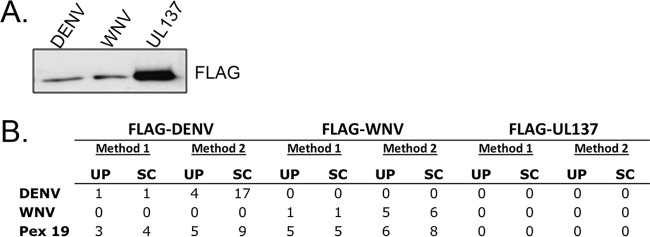

To identify host cell proteins that interact with flavivirus capsid proteins, HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged WNV and DENV capsid proteins. Proteins were extracted from the transfected cells under physiological salt conditions (method 1) or under high-salt conditions followed by dialysis under physiological salt conditions (method 2). The resulting lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG resin. Protein complexes were eluted from the resin and then subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. As a control, we used FLAG-tagged UL137, a tegument protein from human cytomegalovirus (CMV) (19) that is similar in size to flavivirus capsid proteins (Fig. 1A) and that is also targeted to the nucleus. Our interest was primarily in identifying host proteins that bind to both WNV and DENV capsid proteins, and one candidate fitting these criteria is the peroxisome biogenesis factor, Pex19 (Fig. 1B). WNV and DENV capsid-Pex19 complexes were recovered under both extraction conditions, whereas UL137 pulldowns did not contain Pex19. In addition, Pex19 was not recovered in similar experiments performed with CMV UL35 and Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 proteins (15–17). Note that the low peptide recovery of all of the bait proteins stems from their small sizes; the actual relative recoveries of proteins were determined by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). These data showed that, despite its lack of interaction with Pex19, UL137 was recovered more efficiently than the WNV and DENV capsid proteins. Therefore, the results indicate that the Pex19 interaction is specific for the WNV and DENV capsid proteins.

FIG 1.

Recovery of FLAG-tagged DENV and WNV capsid proteins from human cells identifies an interaction with Pex19. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged DENV or WNV capsid protein or with FLAG-tagged UL137 from human cytomegalovirus (negative control). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were lysed in physiological salt buffer (method 1) or high-salt buffer followed by dialysis (method 2). The FLAG-tagged proteins and their interactors were recovered from lysates on anti-FLAG resin. (A) Immunoblot of the proteins (50%) isolated using method 1 (probed with anti-FLAG antibody) showing that all three viral proteins were recovered. (B) The recovered proteins were trypsinized and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The recovery of peptides from Pex19 and the tagged DEN and WNV proteins is shown. UP, number of unique peptides; SC, total spectral counts (total number of peptides).

Pex19 is essential for the function of peroxisomes, as it is required early in the biogenesis pathway, before the import of matrix proteins (7, 20). Given that peroxisomes have been implicated in antiviral signaling in response to RNA virus infections (8, 9), we elected to examine the potential effect of flavivirus capsid protein expression on peroxisome biogenesis. First, we employed reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation to verify the interaction between Pex19 and capsid proteins. The data presented in Fig. 2 confirmed that Pex19 forms stable complexes with capsid proteins in WNV- and DENV-infected cells.

FIG 2.

Pex19 forms stable complexes with capsid proteins during flavivirus infection. A549 cells were infected with WNV or DENV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 3). Forty-eight hours later, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-capsid (Cap) and anti-Pex19 antibodies. The levels of capsid proteins and Pex19 were detected in whole-cell lysates (WCL) and immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. The secondary antibodies were Dylight 680 donkey anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG and Dylight 800 donkey anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, or anti-guinea-pig IgG.

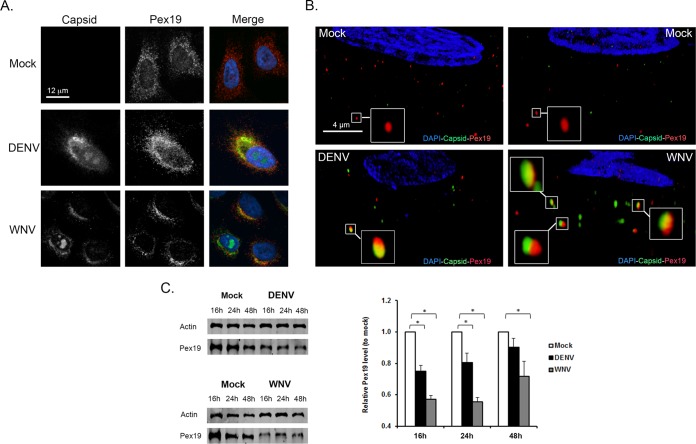

Next, we examined the effects of WNV and DENV infection on Pex19 distribution. In mock-infected samples, most Pex19 exhibited a fine punctate localization that radiated out from the perinuclear region (Fig. 3A). Conversely, in flavivirus-infected cells, Pex19 was confined largely to juxtanuclear areas that were enriched for capsid protein. Using superresolution microscopy, we were able to further resolve the capsid- and Pex19-containing structures (Fig. 3B). A number of cytoplasmic elements that contained Pex19 and flavivirus capsid proteins were clearly visible, but in most cases, the capsid protein and Pex19 signals did not overlap. In addition to affecting the distribution of Pex19, infection with DENV or WNV resulted in significant degradation of Pex19 (Fig. 3C), a process that could explain in part the relatively low level of colocalization between capsid proteins and Pex19.

FIG 3.

Redistribution and loss of Pex19 during flavivirus infection. (A and B) A549 cells were infected with WNV or DENV (MOI = 1) and processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy 16 to 48 h postinfection. WNV and DENV capsid proteins were detected using guinea pig polyclonal antibodies and goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546. Pex19 was detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. The images were obtained using spinning-disc confocal (A) and structured-illumination (B) microscopes. The enlarged areas in panel B show structures that contain both Pex19 and capsid proteins. (C) Infection by DENV or WNV leads to decreased Pex19. Immunoblot and quantitative analyses of Pex19 levels in mock-infected and flavivirus-infected cells are presented. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.05.

Peroxisomes are decreased in number in flavivirus-infected cells.

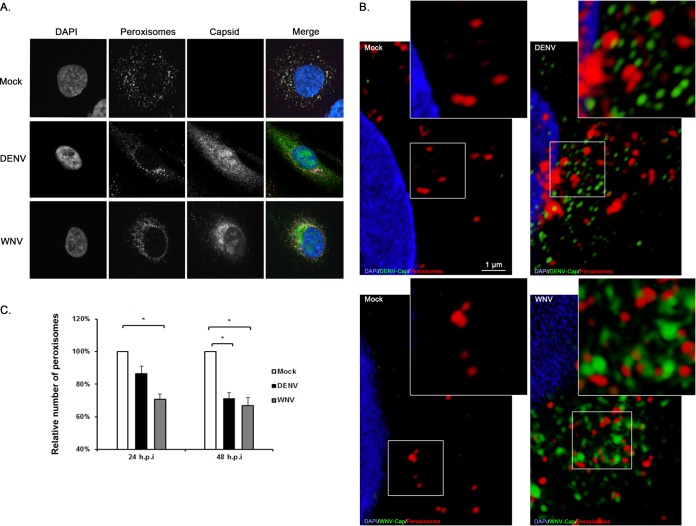

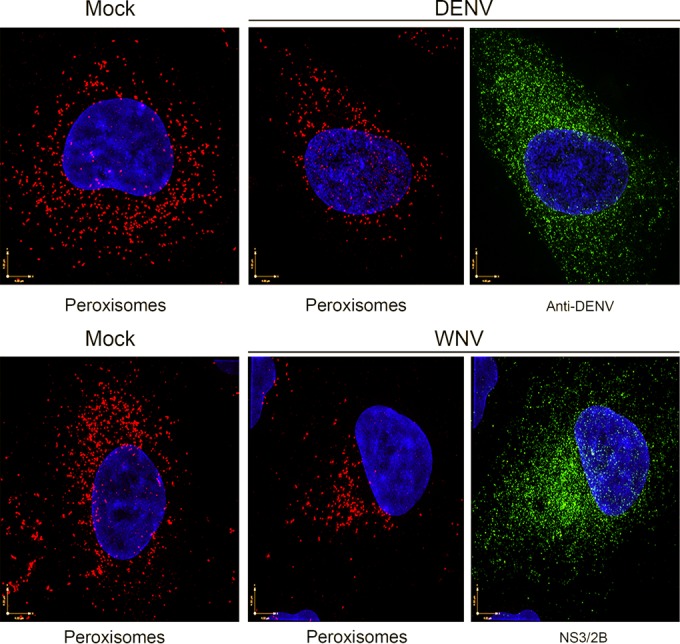

The biogenesis of peroxisomes requires Pex19 (7). As such, if capsid proteins sequester Pex19 from the peroxisomal biogenesis machinery or induce its degradation, fewer peroxisomes should be observed in flavivirus-infected cells. The numbers and morphologies of peroxisomes in mock- and flavivirus-infected cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Peroxisomes were identified using an antibody to the tripeptide SKL, a targeting motif found at the carboxyl termini of many peroxisomal matrix proteins (21). In mock-treated cells, SKL-positive puncta were localized throughout the cytoplasm, including distal regions (Fig. 4A). In contrast, DENV and WNV infections resulted in clustering of peroxisomes to the capsid-positive juxtanuclear regions. However, in contrast to what we observed with Pex19, we did not see evidence of colocalization between capsid proteins and peroxisomes when superresolution microscopy was employed (Fig. 4B). Similarly, we found no evidence to suggest that flavivirus replication complexes associate with peroxisomes (data not shown). As well as clustering of peroxisomes in the juxtanuclear area, flavivirus-infected cells contained significantly fewer peroxisomes than mock-infected cells (Fig. 4C and 5). This was most evident at 48 h postinfection, when an ∼30% decrease in SKL-positive structures was observed in both DENV- and WNV-infected cells.

FIG 4.

Effect of flavivirus infection on peroxisomes. (A) A549 cells were infected with WNV or DENV (MOI = 1) and processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy 24 and 48 h postinfection. Cells infected with DENV or WNV were identified using guinea pig antibodies to the respective capsid proteins and goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546. Peroxisomes were detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to the peroxisomal targeting signal SKL and donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. (B) Superresolution microscopy images of mock-infected and DENV- or WNV-infected cells showing lack of colocalization between capsid proteins and peroxisomes. The insets show enlargements of the boxed areas. (C) The average numbers of SKL-positive structures in mock-infected and flavivirus-infected cells were determined from three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.05.

FIG 5.

Loss of peroxisomes in flavivirus-infected cells as revealed by superresolution microscopy. A549 cells were infected with WNV or DENV and then processed for superresolution microscopy after 48 h. Cells infected with DENV or WNV were identified using human anti-DENV E antibodies or a mouse monoclonal antibody to the WNV NS2B-NS3 complex. Primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-human IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. Peroxisomes were detected with rabbit polyclonal antibodies to SKL and donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. The images were acquired and reconstructed using a DeltaVision OMX structured-illumination microscope.

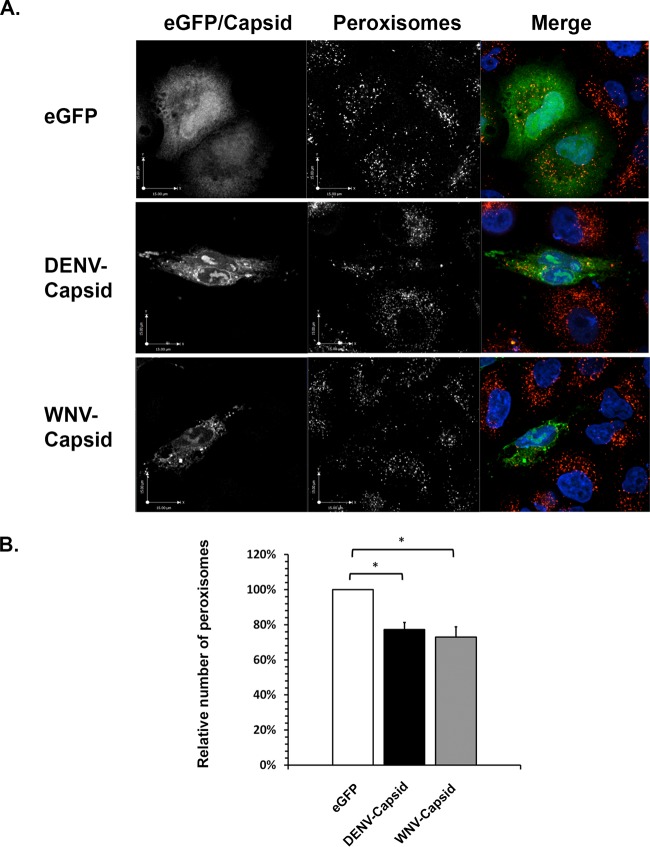

To determine if the effects on peroxisomes observed in flavivirus-infected cells could be recapitulated by expression of capsid proteins, microscopic analysis was conducted on transiently transfected A549 cells. The data presented in Fig. 6A show that, similar to what was observed in flavivirus-infected cells, capsid protein expression resulted in clustering of peroxisomes in the juxtanuclear area of cells. Moreover, quantification of SKL-positive structures revealed that the average number of peroxisomes in capsid-expressing cells was >20% less than in enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-expressing cells (Fig. 6B). However, this effect was less pronounced than that observed in flavivirus-infected cells (Fig. 4C).

FIG 6.

Expression of flavivirus capsid proteins causes loss of peroxisomes. A549 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding DENV or WNV capsid proteins or eGFP (negative control). The cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy 24 h posttransfection. (A) Peroxisomes were detected with rabbit anti-SKL antibodies and donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546. Capsid proteins were detected with guinea antibodies to DENV or WNV capsids and goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. (B) The average numbers of SKL-positive structures in cells expressing eGFP, DENV capsid, and WNV capsid were determined from three independent experiments (minimum of 15 cells). Peroxisome numbers were determined using Volocity image analysis software. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.05.

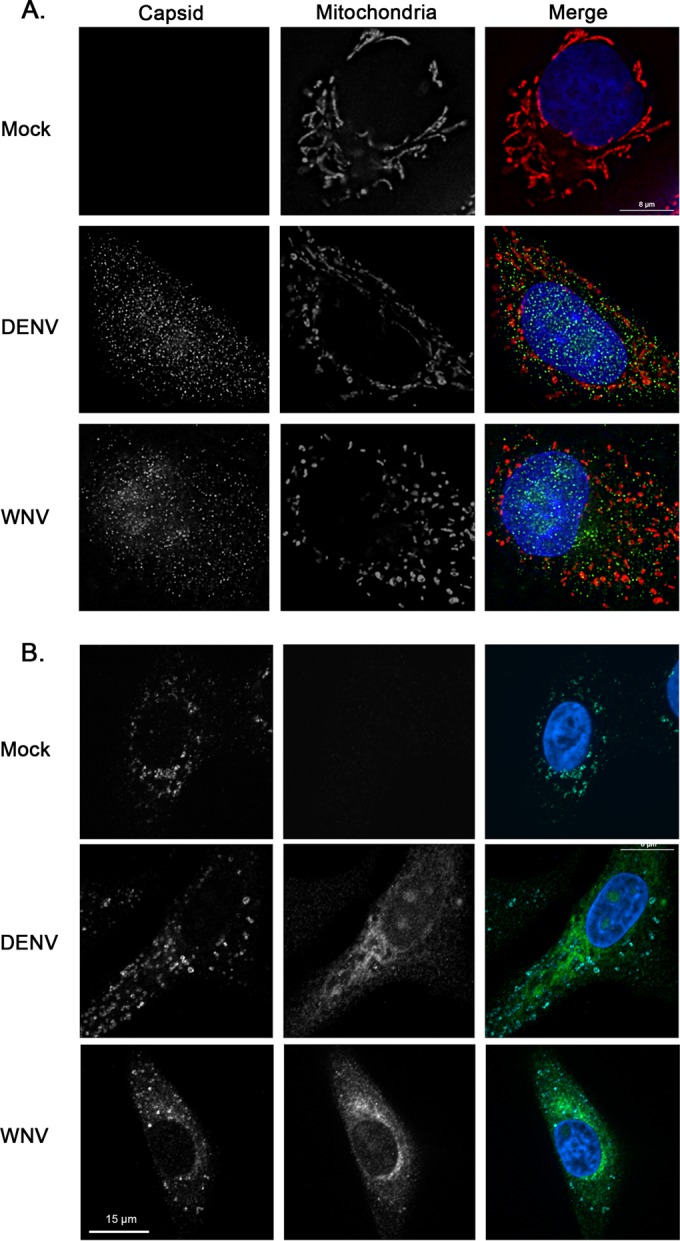

Rearrangement of cellular membranes is a common feature of virus-infected cells (reviewed in reference 22). Therefore, we next investigated whether other membrane-bound organelles, such as mitochondria and lysosomes, which have no known direct role in flavivirus replication, were disrupted by flavivirus infection or capsid protein expression. The data presented in Fig. 7A show that WNV and DENV infections only mildly affected the morphology of mitochondria; specifically, mitochondria in flavivirus-infected cells were more fragmented than those in mock-infected cells, but their overall distribution in the cell was not dramatically different from that in the mock-infected cells. In contrast, we and others have shown that infection of A549 and other cell lines with rubella virus, another positive-strand RNA virus, results in complete collapse of the mitochondrial network to the perinuclear region (23, 24), an effect due to expression of the capsid protein (13). Compared to cells transfected with a plasmid encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) (a negative control), expression of DENV or WNV capsid protein did not noticeably affect the mitochondrial network (data not shown). In contrast to peroxisomes and mitochondria, the distribution of lysosomes was relatively unaffected by flavivirus infection (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Mitochondrial morphology is not dramatically affected by flavivirus infection or expression of capsid proteins. A549 cells were infected with DENV or WNV (MOI = 1). Forty-eight hours later, samples were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Infected cells were identified using guinea pig polyclonal antibodies to capsid proteins and goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. (A) Mitochondria were detected using a monoclonal antibody to the matrix protein p32 and donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546. (B) Lysosomes were detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody to the lysosome membrane protein, LAMP-1, and donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. Cells were viewed by confocal microscopy.

Levels of the peroxisomal matrix enzyme, catalase, are reduced in flavivirus-infected cells.

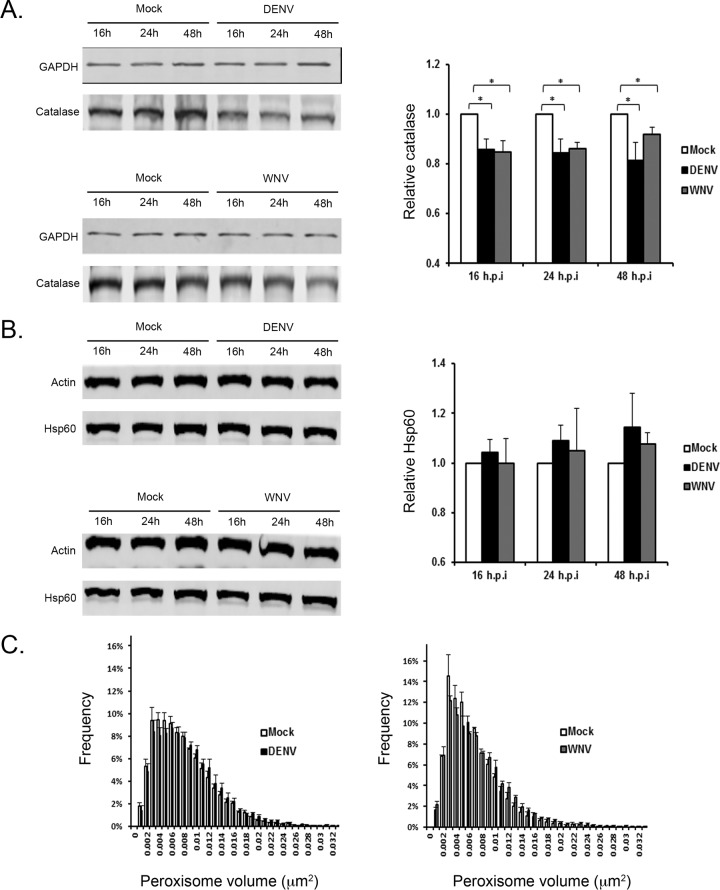

Together, our data are consistent with a scenario in which reducing the pool of Pex19 through capsid protein-dependent sequestration and/or degradation negatively impacts peroxisome biogenesis. If this is indeed the case, we would expect to see a concomitant loss of peroxisomal protein in virus-infected cells. Immunoblotting was used to quantify the relative levels of matrix proteins of peroxisomes and of mitochondria, neither of which is known to be involved directly in flavivirus assembly or replication of RNA. Therefore, if the peroxisome biogenesis defects in DENV- and WNV-infected cells are specific, the levels of resident proteins of mitochondria should be relatively unaffected by flavivirus infection compared to resident proteins of peroxisomes. From the data presented in Fig. 8A, it can be seen that between 16 and 48 h postinfection, levels of catalase, a peroxisomal matrix enzyme, were reduced by >15% at some time points in DENV- and WNV-infected cells. In contrast, the mitochondrial matrix protein Hsp60 was not significantly affected by flavivirus infection (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

Flavivirus infection results in loss of the peroxisomal matrix enzyme, catalase. (A and B) A549 cells were infected with DENV or WNV (MOI = 1); cell lysates were harvested 16, 24, and 48 h postinfection; and the levels of the peroxisomal and mitochondrial matrix proteins, catalase (A) and Hsp60 (B), respectively, were determined by immunoblotting (left) and quantified (right). The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.05. (C) Peroxisome size is not affected by flavivirus infection. A549 cells were infected (MOI = 1) with either DENV or WNV. At 48 h postinfection, the cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Peroxisomes were detected with rabbit polyclonal antibodies to SKL and donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568, and infected cells were identified using human anti-DENV E antibodies or a mouse monoclonal antibody to the WNV NS2B-NS3 complex. Primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-human IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. The images were acquired and reconstructed using a DeltaVision OMX structured-illumination microscope. Volocity software was used to determine the sizes and numbers of peroxisomes in mock-infected and flavivirus-infected cells.

Because the flavivirus-induced loss of the peroxisomal matrix protein catalase (15%) was not as great as the flavivirus-induced reduction in peroxisome numbers (∼30%) (cf. Fig. 4C), we questioned whether the division of peroxisomes was also affected by flavivirus infection. Superresolution microscopy was used to analyze the size and distribution of peroxisomes at 24 to 48 h postinfection. The data presented in Fig. 8C show that large peroxisomes were not overrepresented in DENV- or WNV-infected cells after 48 h. Similar results were observed at 24 h postinfection (data not shown). As such, our data are consistent with a scenario in which flavivirus infection causes a loss of peroxisomal material.

Flavivirus infection suppresses the induction of type III interferon.

A physical or functional relationship between flavivirus and mitochondria has not been demonstrated, but it is well documented that peroxisomes and mitochondria are in close communication and share proteins, including the antiviral signaling protein MAVS (25). Moreover, pharmacological agents, such as fibrates, which are known to dramatically increase peroxisome proliferation, similarly affect mitochondria (26).

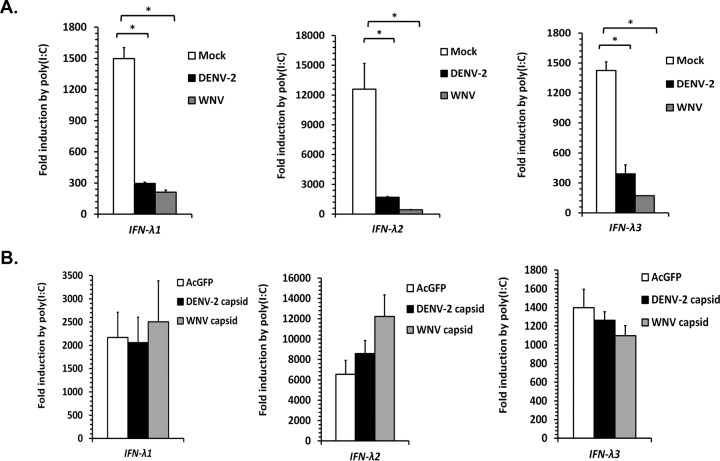

Given the newly discovered role of peroxisomes as signaling platforms for early antiviral signaling (8, 9), we asked whether the reduced numbers of peroxisomes in flavivirus-infected cells were associated with a dampened innate immune response. Peroxisome-dependent signaling leads to increased expression of the antiviral transcription factor IRF1, which acts in a pathway that can be activated using a mimic of viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), poly(I·C). In turn, IRF1 activates transcription of type III interferon (IFN-λ), a process that is reportedly affected by peroxisome abundance (9). As expected, treatment of uninfected A549 cells with poly(I·C) results in rapid and extensive transcription of IFN-λ genes (Fig. 9A). Conversely, flavivirus infection strongly blocked poly(I·C)-induced IFN-λ expression. Similar results were observed in DENV- and WNV-infected HEK293T and Vero cells (data not shown). In contrast, induction of IFN-λ was not significantly impaired by expression of flavivirus capsid proteins in transfected cells (Fig. 9B).

FIG 9.

Flavivirus infection inhibits poly(I·C)-induced expression of type III interferon. (A) A549 cells were mock treated or infected with WNV or DENV-2 (MOI = 2) for 10 to 12 h. The cells were then transfected with 4 μg of poly(I·C) or pCMV5, an empty-vector negative control, for 12 h to induce expression of IFN-λ genes. The cell lysates were collected and processed for RNA extraction and subsequent qRT-PCR. (B) A549 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing GFP derived from Aequorea coerulescens (AcGFP) alone, AcGFP/myc-DENV-2 capsid or AcGFP/myc-WNV capsid. 48 h postransduction, the cells were transfected with poly(I·C) for 12 h. The cell lysates were collected and processed for RNA extraction and subsequent qRT-PCR. The data are averaged from the results of 3 independent experiments. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.05.

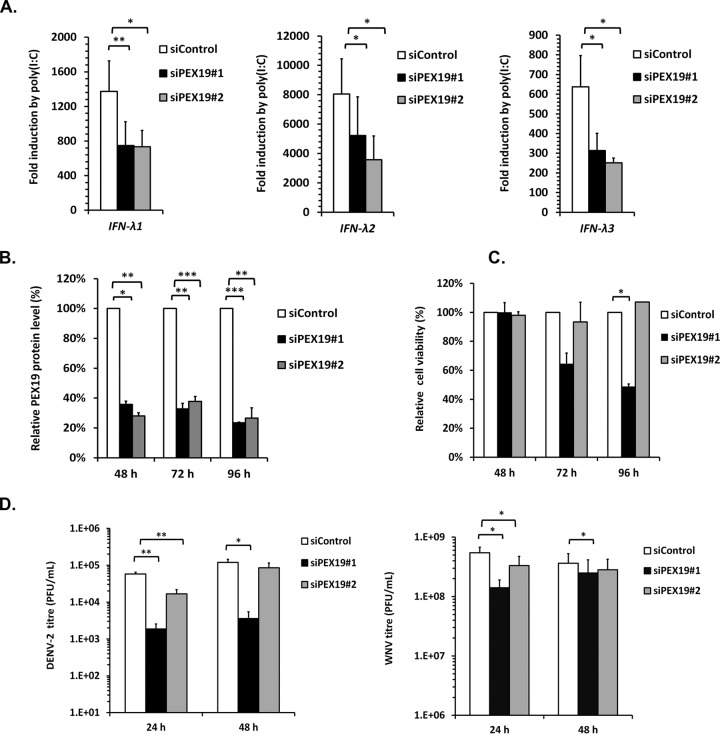

To directly address the question of whether Pex19 is important for expression of type III interferon, we assayed IFN-λ transcription in A549 cells that were treated with pex19-specific siRNAs. The data in Fig. 10 show that reducing Pex19 protein levels by 65 to 75% significantly impaired the production of IFN-λ genes in response to poly(I·C) treatment. These data suggest that flaviviruses actively suppress transcription of type III interferon, in part through reduction of peroxisome numbers. However, decreasing the peroxisome cohort using pex19-specific siRNAs did not result in increased virus replication. Rather, knockdown of Pex19 resulted in small but significant decreases in DENV and WNV titers (Fig. 10D).

FIG 10.

Knockdown of Pex19 reduces poly(I·C)-induced IFN-λ expression and flavivirus titers. (A) A549 cells were treated with a nontargeting siRNA (siControl) or Pex19-specific siRNAs for 48 h. The cells were then transfected with 4 μg of poly(I·C) for 12 h to induce IFN-λ expression or with an empty plasmid vector, pCMV5. The cell lysates were processed for RNA extraction and subsequent qRT-PCR. (B) To determine knockdown efficiency, lysates from siRNA-transfected cells were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-Pex19 antibodies. Quantification was performed using Li-COR software. ***, P < 0.001. (C) The effect of Pex19 knockdown on cell viability assay was determined by counting viable cells at different time points posttransfection. (D) A549 cells transfected with siRNAs for 48 h were infected with DENV-2 or WNV at an MOI of 0.5. At 24 and 48 h postinfection, the viral titers in the cell supernatants were determined. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (n = 4).

DISCUSSION

It is well established that RNA viruses rely on cellular membranes for replication of their genomes and, in many cases, for the entry and assembly of virions. Flaviviruses use membranes of the endocytic pathway for cell entry, whereas RNA replication and virus assembly are associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (reviewed in reference 27). After budding into the lumen of the ER, flavivirus virions travel through the Golgi complex en route to the plasma membrane, where they are secreted into the extracellular medium. Due to their involvement in innate immunity, mitochondrial membranes could be envisaged as having an adversarial role against flaviviruses and other viruses. Unlike endosomes, the ER, the Golgi complex, and mitochondria, peroxisomes have received comparatively little attention with regard to their roles in virus biology; one reason is that the vast majority of peroxisomal studies employ Saccharomyces cerevisiae model systems (reviewed in reference 28).

For the first time, we show that flavivirus infection has a dramatic effect on peroxisome numbers and distribution. While the effects of flavivirus infection on peroxisomes may be due to multiple factors, the observation that WNV and DENV capsid proteins bind to the peroxisome biogenic factor Pex19 provides a plausible mechanism for peroxisome loss in infected cells. Pex19 has a variety of functions in organelle biogenesis, including acting as a chaperone for the insertion of proteins into the peroxisomal membrane and facilitating the egress of preperoxisomal vesicles from the ER (29–31). Levels of Pex19 were significantly lower in flavivirus-infected cells, which might be expected to compromise peroxisome biogenesis in these cells. Our findings are consistent with a scenario in which sequestration of Pex19 by flavivirus capsid proteins impairs peroxisome biogenesis, thereby resulting in decreased numbers of the organelles.

Tombusviruses, which are small positive-strand RNA viruses, replicate on peroxisomal membranes in plant cells (32). Of note, Pex19 is an important host factor for tombusvirus replication, as it binds to the replicase protein p33 and transports it to peroxisomes (33). While the intracellular distribution of Pex19 was markedly altered in flavivirus-infected and capsid-expressing cells, this reorganization is unlikely to be related to a direct role of peroxisomes in flavivirus replication. Specifically, Pex19 redistributed to areas of the cytoplasm that were enriched for capsid protein. However, neither the capsid protein nor viral replication intermediates (dsRNA) were observed to associate with peroxisomes.

Although there is no evidence indicating that peroxisomes serve as sites for the replication and/or assembly of mammalian viruses, a number of potentially significant interactions between pathogenic viruses and peroxisomes or peroxisomal proteins have been reported. The VP4 proteins of all known rotaviruses contain canonical peroxisomal-membrane-targeting sequences, and a pool of VP4 indeed associates with peroxisomes in rotavirus-infected mammalian cells (34). The significance of this phenomenon in virus biology and/or pathogenesis is not known. Multiple studies have shown that the Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus associates with thioesterase, a peroxisomal matrix protein (35, 36). A cohort of Nef and thioesterase colocalizes to peroxisomes in transfected cells; however, targeting of these proteins to peroxisomes is not required for their interaction (37). Ablation of the thioesterase-binding site on Nef by site-directed mutagenesis prevents it from enhancing viral infectivity and downregulating expression of the immune molecule CD4 (38). However, this site is also required for oligomerization of Nef, and as such, it is possible that the observed loss of Nef function was not due to the failure of the viral protein to interact with thioesterase. Finally, the NS1 protein of several influenza virus strains binds to 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, a peroxisomal enzyme involved in the β-oxidation of fatty acids (39). The significance of this interaction was unknown when initially discovered; however, later studies revealed that influenza virus infection alters peroxisome-specific lipid metabolism in a way that is thought to benefit virus replication (40). Indeed, knockdown of Pex19 results in a small but significant decrease in virus replication, an observation that may reflect the very likely possibility that some peroxisomal functions actually benefit flavivirus replication.

As we have discussed above, proteins encoded by pathogenic viruses have been shown to interact with specific components of peroxisomes, with outcomes that are not fully understood. In the present study, we report for the first time the global effect of virus infection on peroxisomes. The impetus for this line of investigation was the observation that flavivirus capsid proteins interact with and alter the distribution and steady-state levels of a critical peroxisome biogenesis factor, Pex19. While it is not clear if or how binding between Pex19 and flavivirus capsid proteins leads directly to Pex19 turnover or loss of function, a dramatic loss of peroxisomes has been observed in response to DENV and WNV infections. In light of the recently discovered role of peroxisomes in transient early antiviral signaling, one obvious benefit of the virus of reducing peroxisome numbers, and consequently peroxisomal function, would be a compromised antiviral defense. A peroxisomal pool of MAVS facilitates activation and then elevated production of the transcription factor IRF1 after viral RNA is detected by RIG-I or MDA-5 in the cytoplasm (8). Induction of type III interferons, which are downstream of IRF1, in response to a viral dsRNA mimic was reduced more than 80% in flavivirus-infected cells. Similarly, flavivirus infection reduced poly(I·C)-induced irf1 expression by more than 50% (data not shown). Together, these data are consistent with a scenario in which reduction of the peroxisomal “signaling platform” leads to an impaired ability of the cell to respond to the detection of viral RNA. Given that flaviviruses replicate relatively slowly compared to other positive-strand RNA viruses, such as alphaviruses and picornaviruses, interfering with early antiviral signaling pathways may provide a critical window of opportunity for the virus in which to establish replication and deployment of other mechanisms that interfere with later-acting but more potent antiviral signaling pathways, including the interferon response.

A remaining challenge is to understand how flavivirus infection leads to loss of peroxisomes. While expression of capsid proteins in the absence of other viral proteins leads to changes in peroxisomal distribution and significant loss of peroxisomes, antiviral signaling as assayed by the induction of irf1 and ifnλ1, -2, and -3 mRNAs was not significantly affected. That does not rule out the possibility that capsid proteins are solely responsible for loss of perixosomes and concomitant dampened antiviral signaling. First, there are likely to be much higher levels of capsid proteins in flavivirus-infected cells than in cells transduced with lentiviruses encoding capsid protein. In addition, there may be a threshold of the Pex19 protein level/activity below which dramatic loss of peroxisomes occurs. If the level of capsid protein in transfected cells is not high enough to interfere with Pex19 activity beyond a critical threshold, significant loss of peroxisomes would not occur, in which case irf1 and type III interferon induction would not be affected. Moreover, the fact that flavivirus infection, which results in as much as a 35% decrease in Pex19 protein levels, more potently blocks lambda interferon expression than Pex19 knockdown (>75% reduction in Pex19) suggests that other viral factors affect antiviral signaling from peroxisomes.

As to the cellular mechanism by which Pex19 is degraded during flavivirus infection, our experiments using proteasomal and lysosomal inhibitors did not lead to conclusive results (data not shown). Given that autophagy has been implicated in various aspects of flavivirus infection, including elimination of damaged mitochondria during hepatitis C virus infection (41), we explored whether pharmacological inhibition of this degradative pathway would protect against peroxisome loss in DENV- and WNV-infected cells. Unfortunately, we did not obtain conclusive results, a situation that may be related to the possibility that interfering with cellular degradative pathways, including those linked to the proteasome and autophagy, can affect flavivirus replication (reviewed in reference 42).

In addition to further understanding how flavivirus infection leads to loss of peroxisomes and associated antiviral signaling, more research is needed to precisely define how type III interferons affect the replication and/or pathogenicity of these pathogens. Presently, there is little evidence to suggest that lambda interferon effectively blocks flavivirus replication; however, in animal models at least, the cytokine protects against WNV neuroinvasion (43). By increasing the barrier function of tight junctions in epithelial and endothelial layers, lambda interferon may prevent the spread of flaviviruses from the bloodstream and lymph to vital organs in the host. As such, elucidating the way in which flaviviruses, and potentially other blood-borne pathogens, affect peroxisome-dependent signaling may lead to novel antiviral therapies that limit viral spread.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eileen Reklow and Valeria Mancinelli for technical support and Anil Kumar for helpful discussions.

J.Y. and A.K. are supported by postdoctoral fellowship awards from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions. T.C.H. and L.F. are supported by awards from the Canada Research Chairs. This work was supported by operating funds from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to T.C.H. and L.F. T.C.H. also received funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2013. Flaviviruses, p 747–794. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urbanowski MD, Hobman TC. 2013. The West Nile virus capsid protein blocks apoptosis through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent mechanism. J Virol 87:872–881. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02030-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbanowski MD, Ilkow CS, Hobman TC. 2008. Modulation of signaling pathways by RNA virus capsid proteins. Cell Signal 20:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moriya K, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Tsutsumi T, Ishibashi K, Matsuura Y, Kimura S, Miyamura T, Koike K. 1998. The core protein of hepatitis C virus induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice. Nat Med 4:1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Z, Hobman TC. 2012. The helicase activity of DDX56 is required for its role in assembly of infectious West Nile virus particles. Virology 433:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Z, Anderson R, Hobman TC. 2011. The capsid-binding nucleolar helicase DDX56 is important for infectivity of West Nile virus. J Virol 85:5571–5580. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01933-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotte K, Girzalsky W, Linkert M, Baumgart E, Kammerer S, Kunau WH, Erdmann R. 1998. Pex19p, a farnesylated protein essential for peroxisome biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 18:616–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixit E, Boulant S, Zhang Y, Lee AS, Odendall C, Shum B, Hacohen N, Chen ZJ, Whelan SP, Fransen M, Nibert ML, Superti-Furga G, Kagan JC. 2010. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 141:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odendall C, Dixit E, Stavru F, Bierne H, Franz KM, Durbin AF, Boulant S, Gehrke L, Cossart P, Kagan JC. 2014. Diverse intracellular pathogens activate type III interferon expression from peroxisomes. Nat Immunol 15:717–726. doi: 10.1038/ni.2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skolnik PR, Rabbi MF, Mathys JM, Greenberg AS. 2002. Stimulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma blocks HIV-1 replication and TNFalpha production in acutely infected primary blood cells, chronically infected U1 cells, and alveolar macrophages from HIV-infected subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 31:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200209010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal N, Kumawat KL, Basu A, Ravindranath V. 2012. Fenofibrate reduces mortality and precludes neurological deficits in survivors in murine model of Japanese encephalitis viral infection. PLoS One 7:e35427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt TA, Urbanowski MD, Kakani K, Law LM, Brinton MA, Hobman TC. 2007. Interactions between the West Nile virus capsid protein and the host cell-encoded phosphatase inhibitor, I2PP2A. Cell Microbiol 9:2756–2766. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beatch MD, Hobman TC. 2000. Rubella virus capsid associates with host cell protein p32 and localizes to mitochondria. J Virol 74:5569–5576. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.12.5569-5576.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aitchison JD, Szilard RK, Nuttley WM, Rachubinski RA. 1992. Antibodies directed against a yeast carboxyl-terminal peroxisomal targeting signal specifically recognize peroxisomal proteins from various yeasts. Yeast 8:721–734. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salsman J, Wang X, Frappier L. 2011. Nuclear body formation and PML body remodeling by the human cytomegalovirus protein UL35. Virology 414:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holowaty MN, Sheng Y, Nguyen T, Arrowsmith C, Frappier L. 2003. Protein interaction domains of the ubiquitin-specific protease, USP7/HAUSP. J Biol Chem 278:47753–47761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik-Soni N, Frappier L. 2012. Proteomic profiling of EBNA1-host protein interactions in latent and lytic Epstein-Barr virus infections. J Virol 86:6999–7002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00194-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen GI, Gingras AC. 2007. Affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) of serine/threonine phosphatases. Methods 42:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salsman J, Zimmerman N, Chen T, Domagala M, Frappier L. 2008. Genome-wide screen of three herpesviruses for protein subcellular localization and alteration of PML nuclear bodies. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuzono Y, Kinoshita N, Tamura S, Shimozawa N, Hamasaki M, Ghaedi K, Wanders RJ, Suzuki Y, Kondo N, Fujiki Y. 1999. Human PEX19: cDNA cloning by functional complementation, mutation analysis in a patient with Zellweger syndrome, and potential role in peroxisomal membrane assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:2116–2121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould SJ, Keller GA, Hosken N, Wilkinson J, Subramani S. 1989. A conserved tripeptide sorts proteins to peroxisomes. J Cell Biol 108:1657–1664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novoa RR, Calderita G, Arranz R, Fontana J, Granzow H, Risco C. 2005. Virus factories: associations of cell organelles for viral replication and morphogenesis. Biol Cell 97:147–172. doi: 10.1042/BC20040058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilkow CS, Weckbecker D, Cho WJ, Meier S, Beatch MD, Goping IS, Herrmann JM, Hobman TC. 2010. The rubella virus capsid protein inhibits mitochondrial import. J Virol 84:119–130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01348-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claus C, Chey S, Heinrich S, Reins M, Richardt B, Pinkert S, Fechner H, Gaunitz F, Schafer I, Seibel P, Liebert UG. 2011. Involvement of p32 and microtubules in alteration of mitochondrial functions by rubella virus. J Virol 85:3881–3892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02492-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belgnaoui SM, Paz S, Hiscott J. 2011. Orchestrating the interferon antiviral response through the mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) adapter. Curr Opin Immunol 23:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoivik DJ, Qualls CW Jr, Mirabile RC, Cariello NF, Kimbrough CL, Colton HM, Anderson SP, Santostefano MJ, Morgan RJ, Dahl RR, Brown AR, Zhao Z, Mudd PN Jr, Oliver WB Jr, Brown HR, Miller RT. 2004. Fibrates induce hepatic peroxisome and mitochondrial proliferation without overt evidence of cellular proliferation and oxidative stress in cynomolgus monkeys. Carcinogenesis 25:1757–1769. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukhopadhyay S, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2005. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:13–22. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JJ, Aitchison JD. 2013. Peroxisomes take shape. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14:803–817. doi: 10.1038/nrm3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Zand A, Braakman I, Tabak HF. 2010. Peroxisomal membrane proteins insert into the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell 21:2057–2065. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones JM, Morrell JC, Gould SJ. 2004. PEX19 is a predominantly cytosolic chaperone and import receptor for class 1 peroxisomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 164:57–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang Y, Morrell JC, Jones JM, Gould SJ. 2004. PEX3 functions as a PEX19 docking factor in the import of class I peroxisomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 164:863–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCartney AW, Greenwood JS, Fabian MR, White KA, Mullen RT. 2005. Localization of the tomato bushy stunt virus replication protein p33 reveals a peroxisome-to-endoplasmic reticulum sorting pathway. Plant Cell 17:3513–3531. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pathak KB, Sasvari Z, Nagy PD. 2008. The host Pex19p plays a role in peroxisomal localization of tombusvirus replication proteins. Virology 379:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohan KV, Som I, Atreya CD. 2002. Identification of a type 1 peroxisomal targeting signal in a viral protein and demonstration of its targeting to the organelle. J Virol 76:2543–2547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2543-2547.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe H, Shiratori T, Shoji H, Miyatake S, Okazaki Y, Ikuta K, Sato T, Saito T. 1997. A novel acyl-CoA thioesterase enhances its enzymatic activity by direct binding with HIV Nef. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 238:234–239. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu LX, Margottin F, Le Gall S, Schwartz O, Selig L, Benarous R, Benichou S. 1997. Binding of HIV-1 Nef to a novel thioesterase enzyme correlates with Nef-mediated CD4 down-regulation. J Biol Chem 272:13779–13785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen GB, Rangan VS, Chen BK, Smith S, Baltimore D. 2000. The human thioesterase II protein binds to a site on HIV-1 Nef critical for CD4 down-regulation. J Biol Chem 275:23097–23105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu LX, Heveker N, Fackler OT, Arold S, Le Gall S, Janvier K, Peterlin BM, Dumas C, Schwartz O, Benichou S, Benarous R. 2000. Mutation of a conserved residue (D123) required for oligomerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein abolishes interaction with human thioesterase and results in impairment of Nef biological functions. J Virol 74:5310–5319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5310-5319.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff T, O'Neill RE, Palese P. 1996. Interaction cloning of NS1-I, a human protein that binds to the nonstructural NS1 proteins of influenza A and B viruses. J Virol 70:5363–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanner LB, Chng C, Guan XL, Lei Z, Rozen SG, Wenk MR. 2014. Lipidomics identifies a requirement for peroxisomal function during influenza virus replication. J Lipid Res 55:1357–1365. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M049148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SJ, Syed GH, Khan M, Chiu WW, Sohail MA, Gish RG, Siddiqui A. 2014. Hepatitis C virus triggers mitochondrial fission and attenuates apoptosis to promote viral persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:6413–6418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards AL, Jackson WT. 2013. How positive-strand RNA viruses benefit from autophagosome maturation. J Virol 87:9966–9972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00460-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazear HM, Daniels BP, Pinto AK, Huang AC, Vick SC, Doyle SE, Gale M Jr, Klein RS, Diamond MS. 2015. Interferon-lambda restricts West Nile virus neuroinvasion by tightening the blood-brain barrier. Sci Transl Med 7:284ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]