ABSTRACT

Infection with the murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) activates the pattern recognition receptors melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) and Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) to induce transcription of type I interferon. Type I interferon is crucial for control of viral replication and spread in the natural host, but the specific contributions of MDA5 signaling to this pathway as well as to pathogenesis and subsequent immune responses are largely unknown. In this study, we use MHV infection of the liver as a model to demonstrate that MDA5 signaling is critically important for controlling MHV-induced pathology and regulation of the immune response. Mice deficient in MDA5 expression (MDA5−/− mice) experienced more severe disease following MHV infection, with reduced survival, increased spread of virus to additional sites of infection, and more extensive liver damage than did wild-type mice. Although type I interferon transcription decreased in MDA5−/− mice, the interferon-stimulated gene response remained intact. Cytokine production by innate and adaptive immune cells was largely intact in MDA5−/− mice, but perforin induction by natural killer cells and levels of interferon gamma, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in serum were elevated. These data suggest that MDA5 signaling reduces the severity of MHV-induced disease, at least in part by reducing the intensity of the proinflammatory cytokine response.

IMPORTANCE Multicellular organisms employ a wide range of sensors to detect viruses and other pathogens. One such sensor, MDA5, detects viral RNA and triggers induction of type I interferons, chemical messengers that induce inflammation and help regulate the immune responses. In this study, we sought to determine the role of MDA5 during infection with mouse hepatitis virus, a murine coronavirus used to model viral hepatitis as well as other human diseases. We found that mice lacking the MDA5 sensor were more susceptible to infection than were mice with MDA5 and experienced decreased survival. Viral replication in the liver was similar in mice with and without MDA5, but liver damage was increased in MDA5−/− mice, suggesting that the immune response is causing the damage. Production of several proinflammatory cytokines was elevated in MDA5−/− mice, suggesting that MDA5 may be responsible for keeping pathological inflammatory responses in check.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic cells use a variety of molecular sensors to detect pathogens, allowing them to rapidly respond to infections. These sensors are called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), while the structures that they detect are called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The known critical PRRs for RNA viruses are the RIG-I-like receptors (RLR) RIG-I and MDA5, non-RLR helicases such as DHX33 (1), and Toll-like receptors (TLRs, in particular TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8). Since these pathways are among the earliest host responses triggered by infection, studying them is critically important for understanding tropism, virulence, and regulation of host defense during viral infections.

RLRs are expressed in many cell types throughout the body and are therefore the first sensors likely to detect many viral infections, regardless of route of entry or cellular tropism. RIG-I and MDA5 detect different conformations of RNA, and not all RNA viruses are detectable by both. Although first identified in the context of cancer (2, 3), MDA5 has since been shown to have roles in host defense against a wide variety of viruses. MDA5 is critical for type I interferon (IFN-I) induction following coronavirus (4), picornavirus (5), or influenza A virus (6) infection as well as for cytokine production in dendritic cells during norovirus infection (7). Type I interferon constitutes an important component of the early innate response by inducing a large number of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) encoding antiviral effectors. Type I interferon also plays a role in regulating the adaptive immune response in that animals lacking MDA5 signaling (MDA5−/−) demonstrate a variety of immunological defects, including dysregulation of the adaptive immune response during West Nile virus (8) and Theiler's virus infection (9).

The murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a positive-sense RNA virus of Betacoronavirus lineage 2a. Laboratory strains of MHV have a diverse range of cellular and organ tropisms, making them useful model organisms for studying host pathways involved in tropism barriers and virulence (10). MHV strain A59 (MHV-A59) is dualtropic, infecting primarily the liver and the central nervous system, causing moderate hepatitis and mild encephalitis followed by chronic demyelinating disease (11). Intraperitoneal (i.p.) inoculation of MHV-A59 leads to infection of the liver, spleen, and lungs in immunocompetent mice. MHV-A59 can also replicate in the central nervous system when inoculated intracranially; however, it cannot spread more than minimally from the periphery to the central nervous system in immunocompetent mice. MHV-A59 causes hepatitis when it infects the liver and acute encephalitis and chronic demyelination when it infects the central nervous system. Other MHV strains infect the lung and gastrointestinal tracts, making MHV infection a model for multiple human diseases (10, 12). The tropism and virulence of MHV infection are partially determined by immunological factors, as infection of mice lacking type I interferon signaling (Ifnar1−/−) results in expanded organ tropism and greatly reduced survival (4, 13). Although MDA5, but not RIG-I, is known to be necessary for induction of type I interferon in cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages (4) and microglia (data not shown), the importance of MDA5 in induction of interferon during MHV infection has not been well characterized.

Although type I interferon signaling is crucial for host defense against MHV and MDA5 contributes to the production of type I interferon in cell culture, it is unclear to what extent MDA5 contributes to host defense during in vivo infections. In this study, we found that mice lacking MDA5 had levels of viral replication in the liver and spleen similar to those of wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) mice but were nevertheless more susceptible to infection, experiencing decreased survival and increased hepatitis. Furthermore, the ISG response was intact, suggesting a more complicated role for MDA5-induced interferon. Production of proinflammatory cytokines was elevated in MDA5−/− mice, which, taken together with increased hepatitis, suggests that MDA5 signaling limits the damage from pathological proinflammatory immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and mice.

Recombinant MHV strain A59 (referred to here as MHV) has been described previously (14, 15). The titer was determined by plaque assay on murine L2 cell monolayers, as described previously (16). Wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). MDA5-deficient (MDA5−/−) mice were a generous gift from Michael S. Diamond (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). Mice were genotyped and bred in the animal facilities of the University of Pennsylvania. Four- to six-week-old mice were used for all experiments. For infections, virus was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.75% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.). All experiments were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Viral replication burden.

To monitor viral replication, mice were inoculated i.p. with 500 PFU of MHV and sacrificed 3, 5, and 7 days after infection. Following cardiac perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline, organs were harvested, placed in gel saline (an isotonic saline solution containing 0.167% gelatin), weighed, and frozen at −80°C. Organs were later homogenized, and plaque assays were performed on L2 fibroblast monolayers as previously described (16).

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was purified from the lysates of homogenized livers using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting RNA was treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion). A custom TaqMan low-density array (LDA) was designed to include interferon-stimulated gene probes (IRF-7, IRF-9, STAT1, STAT2, ISG15, ISG56, IFNb, IFNa4, RIG-I) and 2 control probes (18S and RPL13a). RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). The 384-well custom LDA plates were loaded with 50 μl of cDNA and 50 μl of 2× TaqMan Universal PCR master mix and run on a 7900 HT Blue instrument (Applied Biosystems). The data were analyzed using SDS 2.3 software. The same genes were also assayed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (qRT-PCR) as follows. RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) to produce cDNA and then amplified using primers obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The sense and antisense primer sequences are available upon request. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on an iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). mRNA was quantified as ΔCT values (where CT is threshold cycle) relative to beta actin or 18S rRNA mRNA levels. The ΔCT values of infected samples were expressed as fold changes over the ΔCT values of mock samples (log10).

Cell isolation from the spleen and liver.

Wild-type and MDA5-deficient (MDA5−/−) mice were infected i.p. with 500 PFU of MHV, and organs were subsequently harvested after cardiac perfusion with PBS. Splenocytes were rendered into single-cell suspensions through a 70-μm filter, after which red blood cells were selectively lysed by incubating for 2 min in a 0.206% Tris-HCl–0.744% NH4Cl solution. Livers were homogenized mechanically, and then lysates were centrifuged through a Percoll gradient to obtain a single-cell suspension.

Surface marker and intracellular cytokine staining.

Intracellular cytokine staining was performed on single-cell suspensions of splenocytes following a 4-h incubation with brefeldin A (20 μg/ml; Sigma) and the MHV peptides M133 (major histocompatibility complex class II [MHC-II]; 4 μg/ml; Biosynthesis) and S598 (MHC-I; 9.3 μg/ml; Biosynthesis). T cells, natural killer cells, and natural killer T cells were stained with the following antibodies: CD3 (eBioscience clone 17A2), CD4 (eBioscience clone GK1.5), CD8 (eBioscience clone 53-6.7), CD44 (eBioscience clone IM7), CD11a (Biolegend clone M17/4), PD-1 (eBioscience clone RMP1-30), βTCR (eBioscience clone H57-597), γδTCR (Biolegend clone GL3), perforin (eBioscience clone MAK-D), and interferon gamma (eBioscience clone XMG1.2). For innate cell immunophenotyping, cells were stained with the following antibodies: CD45 (Biolegend clone 30-F11), Ly6G (Biolegend clone 1A8), Ly6C (Biolegend clone HK1.4), CD11b (eBioscience clone M1/70), CD11c (Biolegend clone N418), CD3 (Biolegend clone 145-2C11), CD19 (BD clone 1D3), and NK1.1 (eBioscience clone PK136). For dendritic cell (DC) phenotyping experiments, cells were stained with the following antibodies: CD11b (eBioscience clone M1/70), CD11c (Biolegend clone N418), CD3 (eBioscience clone 17A2), CD19 (eBioscience clone 1D3), NK1.1 (eBioscience clone PK136), CD45 (eBioscience 30-F11), CD86 (Biolegend clone GL-1), CD80 (Molecular Probes clone 16-10A1), MHC-II (eBioscience clone M5/114.15.2), B220 (Life Technologies clone RA3-6B2), and PDCA-1/CD317 (eBioscience 129c). Staining for interferon gamma was performed after permeabilization with the Cytofix/cytoperm Plus fixation/permeabilization kit (BD). Following staining, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on an LSR II instrument (Becton Dickinson), and the resulting data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar).

Liver histology.

Livers were harvested from sacrificed mice and fixed for 24 h in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Four or five nonoverlapping fields, each 9 by 106 μm2 in area, were selected, the inflammatory foci on each field were counted, and the mean was determined. Samples in which foci had coalesced into a continuous confluence were scored as too numerous to count (TNTC).

T cell depletions.

Mice were inoculated with antibody i.p. 2 days prior to, and 4 and 6 days after, infection with MHV. Mice received either a negative-control antibody (LTF-2; Bio X Cell) or a cocktail of a CD4-depleting antibody (GK1.5; Bio X Cell) and a CD8-depleting antibody (2.43; Bio X Cell). All antibodies were at a 250-μg/ml concentration.

RESULTS

MDA5−/− mice are more susceptible to MHV infection.

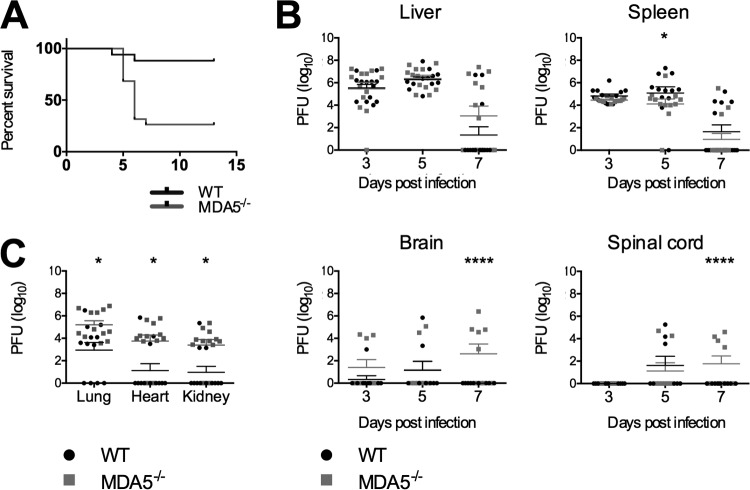

MHV-A59 is a dualtropic strain infecting primarily the liver and the central nervous system of WT C57BL/6 mice. We (4) and others (13) have shown previously that mice lacking the type I interferon receptor (Ifnar1−/− mice) are acutely susceptible to MHV infection. Infection of Ifnar1−/− mice results in spread to multiple organs not usually infected in immunocompetent mice and 100% lethality by day 2 postinfection. MHV has been shown to induce type I interferon via two pathways, MDA5 (4) and TLR7 (13) signaling. To determine whether mice lacking MDA5 signaling were more or less vulnerable to infection with MHV, we infected MDA5−/− mice intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 500 PFU of dualtropic MHV, approximately 1/10 of a 50% lethal dose of this virus in wild-type C57BL/6 mice. As expected, this dose was nonlethal in all but a small minority of wild-type mice but lethal in roughly 75% of the MDA5−/− animals by 7 days postinfection (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

MDA5−/− mice have heightened susceptibility to MHV infection. Survival was monitored after i.p. inoculation of 500 PFU MHV. Results were statistically significant by the Mantel-Cox test (A). Viral titers in the liver, spleen, brain, and spinal cord were determined by plaque assay 3, 5, and 7 days after i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV (B) and at 5 days postinoculation in the lungs, heart, and kidney (C). For panels B and C, statistical significance was determined by a two-part test using a conditional t test and proportion test. Bars represent the means. Data for all panels were pooled from two independent experiments.

Following i.p. inoculation, MHV replicates in the liver and several other organs of C57BL/6 (WT) mice, with replication peaking at day 5 postinfection. Although capable of replicating in the central nervous system, MHV does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier of most animals following i.p. inoculation of WT mice (1, 17). Inflammation and necrosis peak in the liver at day 7 postinfection (2, 18, 19). To determine if the absence of MDA5 expression results in increased viral replication relative to WT mice, we infected WT and MDA5−/− animals with 500 PFU of MHV. On days 3, 5, and 7 postinfection, animals were sacrificed and their livers, spleens, brains, spinal cords, hearts, kidneys, and lungs were assessed for viral replication by plaque assay. Mean viral titers in the liver and spleen were similar for WT and MDA5−/− mice (Fig. 1B), suggesting that MDA5 is not required to control the infection in those organs. However, in the absence of MDA5, increased viral titers were observed in other organs. Replication was increased in the lungs, kidney, and heart (Fig. 1C), with a larger number of MDA5−/− mice than WT mice having infection at those sites (Fig. 1C). Similarly, viral spread from the periphery to the central nervous system was increased in MDA5−/− mice (Fig. 1B), suggesting that MDA5 signaling contributes to the blood-brain barrier and other tropism barriers.

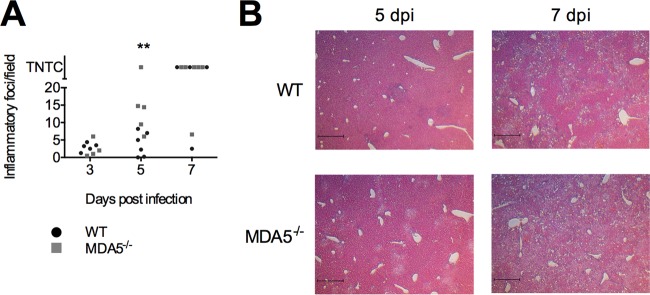

The severity levels of liver damage in WT and in MDA5−/− mice were compared by hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver sections from mice sacrificed on days 3, 5, and 7 postinfection. The inflammatory foci in four or five nonoverlapping fields of view, each 9 by 106 μm2, were counted, and the mean number was determined. In some samples, the foci had combined to form a continuous confluence covering the entirety of the section. These samples were scored as too numerous to count (TNTC). Despite the similarity in viral replication in the liver between MDA5−/− and WT mice, the prevalence of inflammatory foci was higher in MDA5−/− mice (Fig. 2A). The increased severity of liver damage despite unchanged viral replication in MDA5−/− mice compared to WT mice suggests that an immunopathological mechanism may underlie the greater susceptibility of MDA5−/− mice to MHV infection.

FIG 2.

MDA5−/− mice have increased pathology in the liver. Three, 5, and 7 days following i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, livers were removed, fixed, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Four or five nonoverlapping fields of view, each 9 by 106 μm2, were chosen at random, the number of inflammatory foci was determined, and the mean was calculated (A). Statistical significance was determined by a two-part test using a conditional t test and proportion test. Samples in which foci had coalesced into a continuous confluence were scored as too numerous to count (TNTC). Representative fields are shown in panel B. Scale bar, 500 μm. Data are from one experiment.

The mRNA expression of type I interferon, but not interferon-stimulated genes, is reduced in MDA5−/− mice.

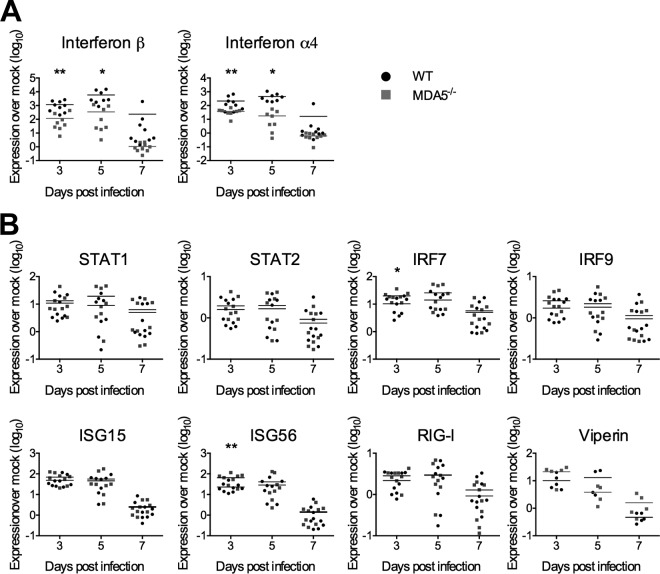

The primary role of MDA5 is to upregulate type I interferon expression in response to viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). We hypothesized that mice lacking MDA5 would express less interferon, which should in turn limit the activation of transcription of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). To test this hypothesis, we isolated RNA from the livers of infected WT and MDA5−/− mice collected 3, 5, and 7 days postinfection and performed quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Induction of IFN-β and IFN-α4 mRNA expression in the livers of infected mice relative to mock-infected mice was lower for MDA5−/− mice than for WT mice on days 3 and 5 after infection, although this difference was transient and was no longer evident by day 7 postinfection (Fig. 3A). We hypothesized that a biologically relevant decrease in interferon expression would have downstream effects, most notably on induction of antiviral ISG expression, which could lead to the observed disease phenotype, and therefore performed qRT-PCR to measure the expression of a representative panel of ISGs in the liver. Surprisingly, ISG expression in MDA5−/− mice was intact for almost all genes at almost all time points despite the reduced induction of type I interferon mRNA (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that if the increased susceptibility of MDA5−/− mice to MHV infection is due to decreased interferon expression, it is not a result of reduced ISG expression.

FIG 3.

Interferon, but not interferon-stimulated gene, expression is reduced in MDA5−/− mice. On days 3, 5, and 7 following i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, RNA was isolated from the liver. Gene expressions for type I interferons (A) and ISGs (B) were quantified by qRT-PCR and expressed as fold changes from values for mock-infected mice. Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t test. Outliers were eliminated by a ROUT test (Q = 1%). Bars represent the means. Data were pooled from two independent experiments, with the exception of viperin mRNA quantification, which was performed once.

Innate inflammatory cell recruitment is largely intact in MDA5−/− mice, but activation of dendritic cells is elevated.

Shortly after infection, a diverse set of innate inflammatory cells infiltrate the sites of viral replication, where they are often instrumental in restricting infection, regulating the adaptive immune response and causing immunopathology. We hypothesized that the loss of MDA5 signaling might cause dysregulation of the inflammatory infiltrate. A delay or reduction in magnitude of the recruitment could allow the virus to replicate to higher levels or in different organs or cell types, while overexuberant recruitment could lead to tissue damage, as observed in the livers of MDA5−/− mice (Fig. 2).

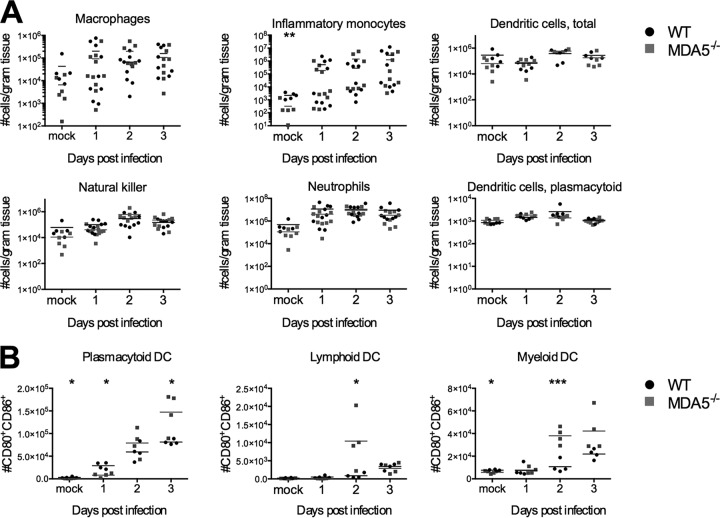

To determine if there were differences in the kinetics or magnitude of recruitment, we isolated and immunophenotyped cells from the livers of infected mice shortly after i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU of MHV (Fig. 4A). We observed no differences in the kinetics or magnitude of recruitment of macrophages (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G− CD11c− CD11b+ F4/80+), dendritic cells (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G− CD11c+), plasmacytoid dendritic cells (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G− CD11c+ B220+PDCA-1+), neutrophils (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G+), natural killer cells (CD3− CD19− NK1.1+CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G−), or inflammatory monocytes (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6-C+Ly6-G−), indicating that early infiltration is largely independent of MDA5 signaling.

FIG 4.

Innate inflammatory cell recruitment is largely intact in MDA5−/− mice, but activation of dendritic cells is elevated. On days 1, 2, and 3 following i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, mice were sacrificed, organs were harvested, and single-cell suspensions derived from the liver (A) or spleen (B) were immunophenotyped by staining with cell type-specific antibodies and analysis by flow cytometry. The total numbers of macrophages (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G− CD11c− CD11b+ F4/80+), neutrophils (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G+), natural killer cells (CD3− CD19− NK1.1+CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G−), inflammatory monocytes (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6-C+Ly6-G−), and total dendritic cells (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ Ly6-C− Ly6-G− CD11c+) are shown, normalized by the mass of the tissue (A). Surface expression of the activation markers CD80 and CD86 was assessed on splenic plasmacytoid (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ CD11c+ B220+PDCA-1+), lymphoid (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ CD11c+ CD11b−), and myeloid (CD3− CD19− NK1.1− CD45+ CD11c+ CD11b−) dendritic cells, and the total number of CD80+ CD86+ DCs of each subtype is shown (B). Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t test. Bars represent the means. Data were pooled from two independent experiments.

We also assessed the activation phenotype of plasmacytoid, lymphoid, and myeloid dendritic cells (DCs). CD80 and CD86, coactivation markers utilized by DCs during T cell priming (20, 21), are used as a marker of activation. Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) are a major producer of type I interferon during MHV infection and rely on TLR7 rather than MDA5 to detect MHV (3, 13). pDC-dependent type I interferon production should be intact in MDA5−/− mice, which may account for the intact ISG response. The coexpression of CD80 and CD86 on pDCs in MDA5−/− mice was compared to that in wild-type mice. The number of CD80+ CD86+ pDCs was lower on day 1, equal on day 2, and higher on day 3 postinfection in the MDA5−/− mice (Fig. 4B). We speculate that the larger number of activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells at later time points may lead to higher production of interferon driving expression of ISGs even in the absence of MDA5-dependent interferon. However, TLR7-dependent interferon may also account for the interferon present in MDA5−/− mice, independent of pDC activation.

Lymphoid and myeloid DCs are involved in T cell priming. The coexpression of CD80 and CD86 was higher in these populations in MDA5−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 4B). This may suggest that T cell priming is more robust in MDA5−/− animals.

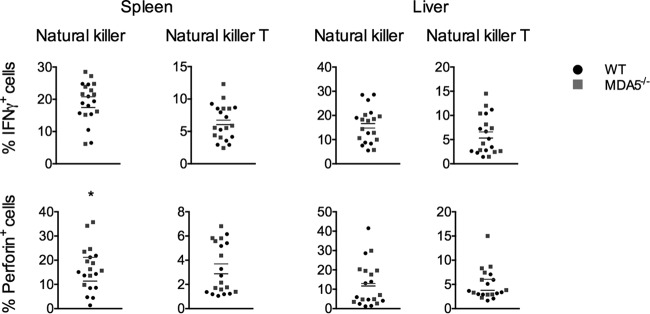

Although the magnitude and kinetics of natural killer cell infiltration into the liver were independent of MDA5 signaling (Fig. 4A), the function of these cells, as well as that of the related natural killer T cells, is dependent on their production of interferon gamma and perforin, and an MDA5-dependent defect in cytokine production could alter their efficacy without affecting the size of the populations. To test whether cytokine production in either cell population was dependent on MDA5 signaling, we isolated cells from the spleen and liver 5 days after infection and assessed their cytokine production by intracellular staining and flow cytometry (Fig. 5). The percentages of each population producing interferon gamma or perforin were similar between genotypes, with the exception of natural killer cells isolated from the spleen, which exhibited elevated perforin production in mice lacking MDA5 signaling. Perforin is a driver of harmful pathology in many contexts (22–25) and may be so in the context of MHV infection as well. Elevated perforin production could lead to either increased liver damage, decreased survival, or both.

FIG 5.

Cytokine production by natural killer and natural killer T cells in MDA5−/− mice is similar to or greater than that observed in WT mice. WT and MDA5−/− mice were sacrificed 5 days after i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, spleens and livers were harvested, and single-cell suspensions derived from the organs were incubated with brefeldin A for 3 h and immunophenotyped by staining with cell type-specific antibodies. Cells were permeabilized and stained with antibody specific to interferon gamma and perforin and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Natural killer (CD3− NK1.1+) and natural killer T cells (CD3+ NK1.1+) were assessed. Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t test. Bars represent the means. Data were pooled from two independent experiments.

Effect of MDA5 on the T cell response.

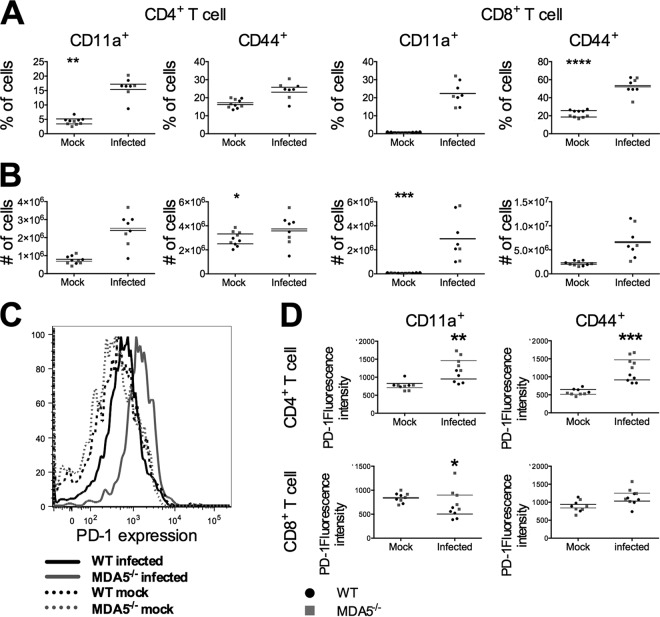

A functional T cell response is essential for clearance of MHV infection. Both CD4 and CD8 T cells, as well as perforin and granzyme and the proinflammatory cytokine interferon gamma, have been established to be necessary (4, 26). B cells appear to be relevant only during a later stage of acute infection, at a time point after we see death among MDA5−/− mice (27, 28). Given that MDA5 can in some contexts be important for regulating the T cell response (5, 8, 9) and that dendritic cells express higher levels of the coactivating receptors CD80 and CD86 in MDA5−/− mice, we hypothesized that CD4 and/or CD8 T cells are dysregulated in MDA5−/− animals. This could result in either a less effective T cell response that is unable to control the virus or an overexuberant T cell response that produces pathology. To determine whether the T cell response was intact, we compared the activation states of CD4 and CD8 T cell populations isolated from the spleens of WT and MDA5−/− mice 7 days postinfection. Isolated cells were stimulated with the M133 (class II) and S598 (class I) MHV-encoded peptides, which are the immunodominant class I and II peptides during MHV infection (29, 30). Following stimulation, the presence of the surface activation markers CD44 and CD11a was analyzed by flow cytometry. The CD4 and CD8 T cell populations from the spleens of MDA5−/− animals were similar to those from WT mice in terms of both the percentage of cells positive for each activation marker (Fig. 6A) and the total number of cells positive for each (Fig. 6B). Statistically significant differences between the genotypes are present in mock samples. However, these are minimal and we believe them to have no biological significance.

FIG 6.

T cell activation is independent of MDA5 signaling. Day 7 following i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were derived from the spleens of wild-type and MDA5−/− mice. Cells were immunophenotyped by staining with cell type-specific antibodies and analysis by flow cytometry. The percentage (A) and total number (B) of CD4 (CD3+ CD4+) and CD8 (CD3+ CD8+) T cells with elevated surface expression of CD44 and CD11a are shown. Expression of PD-1 (representative image in panel C) was assessed on CD44+ and CD11a+ CD4 and CD8 T cells (D). Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t test. Bars represent the means. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

We also found that CD11a+ CD4, CD44+ CD4, and CD11a+ CD8 T cells from MDA5−/− mice displayed a higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 staining (Fig. 6C and D). While PD-1 is a marker of functionally defective, exhausted T cells during chronic infection (9, 31), its role in acute infections remains unclear, with it marking both more and less functional T cells, depending on the infectious context (32). The observation of more-severe liver pathology despite comparable viral replication in MDA5−/− mice suggests that PD-1 could be a marker of pathologically overactive T cells during MHV infection. However, a less functional T cell response that is incapable of controlling viral replication could also explain the increased viral spread and decreased survival, so PD-1 may instead be a marker of less activated T cells in this context.

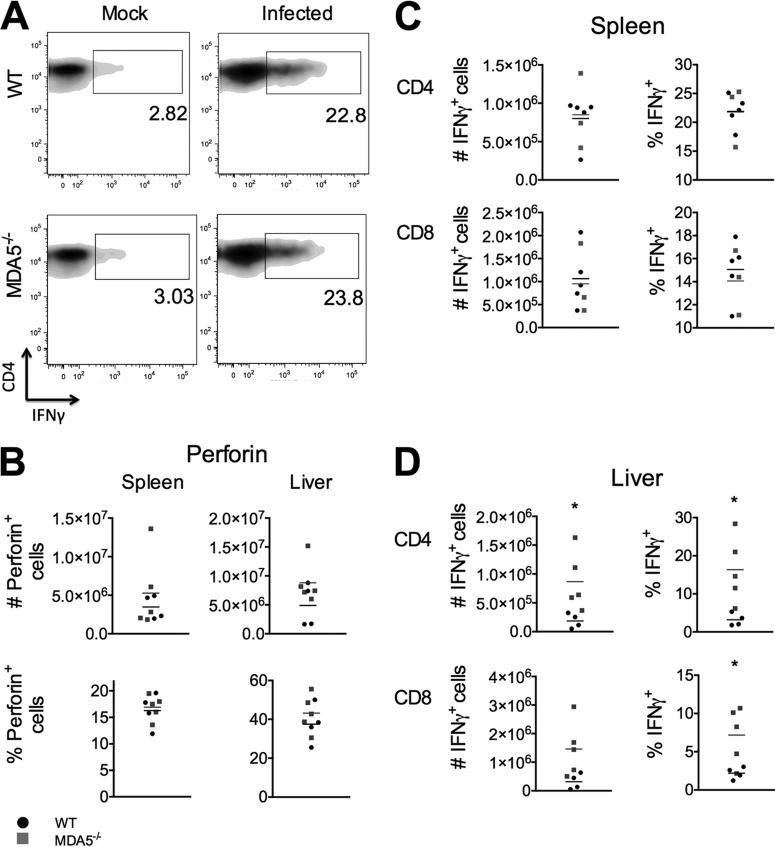

Cytokine production is a major effector function of both CD4 and CD8 T cells. Reduced cytokine production in T cells from MDA5−/− mice could suggest that the adaptive immune response is too weak to control virus, while elevated cytokine levels could suggest a damaging, pathological T cell response. Production of both interferon gamma and perforin was assessed. Perforin production from CD8 T cells in both the spleen and liver in WT mice was similar to that in MDA5−/− mice, indicating that perforin production by T cells is independent of MDA5 signaling (Fig. 7B). Production of interferon gamma was also similar for the genotypes in both CD4 and CD8 T cells in the spleen (Fig. 7C). However, a larger proportion of CD4 and CD8 T cells from the livers of MDA5−/− animals expressed interferon gamma (Fig. 7D). Since viral replication is similar in the liver between genotypes, this may suggest that the adaptive immune response is overexuberant and may be pathological.

FIG 7.

Interferon gamma production, but not perforin production, is elevated in T cells from MDA5−/− mice. WT and MDA5−/− mice were sacrificed 7 days after i.p. inoculation with 500 PFU MHV, spleens and livers were harvested, single-cell suspensions derived from the organs were incubated with immunodominant MHV peptides S598 (class I) and M133 (class II), and cells were immunophenotyped by staining with cell type-specific antibodies. Cells were permeabilized and stained with antibody specific to interferon gamma and perforin and then analyzed by flow cytometry (representative image in panel A). CD8 (CD3+ CD8+) T cells, cells from the spleen and liver, were assessed for expression of perforin (B). CD4 (CD3+ CD4+) and CD8 (CD3+ CD8+) T cells from the spleen (C) and liver (D) were also assessed for expression of interferon gamma. Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t test. Bars represent the means. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

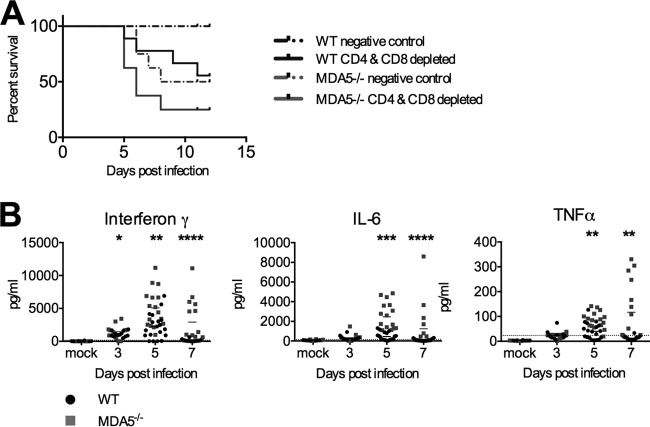

Mice depleted of T cells are more susceptible to MHV infection.

To test the hypothesis that T cells are pathological in the absence of MDA5 signaling, we depleted infected WT and MDA5−/− mice of CD4 and CD8 T cells by administering a cocktail of two depleting antibodies 2 days prior to and 4 and 6 days after infection. While we expected to observe improved survival in mice without T cells, mice depleted of both CD4 and CD8 T cells had reduced survival compared to those mice given a control antibody (Fig. 8A). This suggests that either T cells are not pathological or their pathological role is outweighed by their antiviral role. Regardless, the poor survival of mice lacking MDA5 signaling is likely caused by a factor independent of the T cell response.

FIG 8.

Elevated cytokines, but not T cells, may explain decreased survival of infected MDA5−/− mice. MDA5−/− mice were treated with CD4- and CD8-depleting antibodies or a negative control −2, 4, and 6 days after infection with 500 PFU MHV inoculated i.p. Survival was monitored (A). Data were pooled from two independent experiments. Results are nonsignificant by the Mantel-Cox test. Serum was collected from WT and MDA5−/− mice with intact T cell compartments 3, 5, and 7 days after i.p. inoculation of 500 PFU MHV and analyzed for levels of interferon gamma, IL-6, and TNF-α by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (B). Statistical significance was determined by a two-part test using a conditional t test and proportion test. Data were pooled from four independent experiments (n of 3 to 6).

Proinflammatory cytokines are elevated in the serum of MDA5−/− mice.

As T cells do not appear to be the cause of the low survival of MDA5−/− mice, we considered other drivers of inflammation. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, are produced early during infection by a variety of cell types. These cytokines can contribute to control of pathogens, both before and after development of the adaptive immune response, as well as drive damaging pathological responses. Inflammatory cytokines in the sera of WT and MDA5−/− mice were assayed to determine if levels were altered in the absence of MDA5 signaling. Levels of interferon gamma, IL-6, and TNF-α were all elevated in MDA5−/− mice as early as 5 days after infection (Fig. 8B). This potent response may be the causative agent of both increased pathology and decreased survival in MDA5−/− mice, suggesting that MDA5 has a regulatory role, inhibiting excessively strong proinflammatory cytokine (Fig. 8B) and perforin-mediated cellular (Fig. 5) responses in order to protect the host.

DISCUSSION

Induction of type I interferon expression is an early host response to viral invasion. In the case of some viral models, including MHV infection of its natural host, type I interferon signaling is vital to host survival (4, 10, 11, 13, 33). IFN-α and IFN-β activate the type I interferon receptor in an autocrine and paracrine manner to induce the expression of ISGs. This set of genes includes additional type I interferon subtypes, various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, MDA5 itself, and many other effectors (13, 34). Through these ISGs, type I interferon constitutes a key component of the innate immune response. In addition, interferon is often involved in regulating adaptive immune responses: it can facilitate antigen presentation (35), promote clonal expansion among activated T cells (36, 37), and enhance humoral responses (16, 38).

Type I interferon expression can be induced through numerous signaling pathways, including RLR and TLR signaling. The interplay of these different pathways and the extent to which they are redundant vary by context. We aimed to study the role of MDA5 signaling specifically during MHV infection. Both MDA5 and TLR7 detect MHV infection, and mice lacking TLR7 but not MDA5 are more susceptible to infection than wild-type mice but more resistant than Ifnar−/− mice (13), consistent with our findings here that interferon induced by MDA5 signaling contributes to host protection.

We show here that MDA5−/− mice are highly susceptible to MHV infection, with the majority of MDA5−/− animals dying by 7 to 8 days postinfection while roughly 90% of WT animals survived. Following i.p. inoculation, viral replication levels in the liver and spleen were similar for the two genotypes, but virus more readily infected additional sites, including the central nervous system, in MDA5−/− mice, demonstrating a role of MDA5 signaling in maintaining organ tropism barriers. Despite similar levels of replication, inflammation and pathology in the liver were more severe in the absence of MDA5 signaling.

We compared the host immune response to MHV between WT and MDA5−/− mice and found that many facets of the immune response were largely unchanged in the absence of MDA5 expression. While induction of type I interferon expression is reduced in the livers of MDA5−/− mice, the ISG response was largely intact. The magnitude and kinetics of the innate cellular infiltration of the liver were similar, as were the activation and cytokine production of the T cell response in the spleen. This suggests that, unsurprisingly, many aspects of the immune response are independent of type I interferon signaling.

Despite decreased levels of IFN-β and IFN-α4 in MDA5−/− mice relative to WT mice (Fig. 3A), transcriptional induction of almost all tested ISGs were similar for the two sets of mice. This demonstrates that interferon induced by TLR7 is sufficient to maintain ISG induction even in the absence of MDA5 signaling, highlighting the redundancy within the interferon response. However, despite this redundancy in ISG induction, MDA5−/− mice still succumbed rapidly to infection, suggesting that other downstream effects of MDA5 signaling are necessary for full protection of the host. In addition, these observations indicate that some downstream effects of type I interferon signaling were more susceptible to the loss of MDA5-dependent interferon than others.

The dependence of organ tropism on the route of inoculation makes MHV infection a useful model for studying tropism barriers during viral infection. There is extensive literature demonstrating that type I interferons play an important role in viral tropism (39). However, infection studies in mice genetically deficient in interferon signaling components are often confounded by the difficulty of distinguishing between tropism changes caused by disruption of barriers and tropism changes caused by increased virus replication at primary sites of infection leading to spill-over into other organs. MDA5−/− mice infected with MHV lack that confounding factor because viral replication in the liver and spleen is unchanged. MHV inoculated intracranially replicates in the central nervous system as well as in the liver, spleen, and lungs. However, when inoculated i.p., it does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier and remains restricted to the liver, spleen, and lungs in most infected mice. We have shown that in MDA5−/− mice, MHV was able to expand its tropism despite similar titers in the primary sites of replication, frequently crossing the blood-brain barrier to infect the central nervous system (CNS) after i.p. inoculation and also spreading into and replicating in the heart and kidneys. This demonstrates that the blood-brain barrier and other tropism barriers depend in part on MDA5 signaling. The effect of increased tropism during infection of MDA5−/− mice remains to be elucidated, but we hypothesize that it may lead to increased pathogenesis and may account for the increased virulence observed in mice lacking MDA5. Pathology in organs that are infected at higher rates in MDA5−/− mice than in WT mice may lead to death.

Lethality and liver damage were substantially higher in MDA5−/− than WT mice, but surprisingly, there was not a corresponding difference in viral replication in the liver. This is notably different from previous studies from our lab in which we compared hepatitis induced by several strains of MHV and found an association between pathology and viral replication in the liver in WT mice (18, 19). Since the increased pathology in the livers of MDA5−/− mice is not associated with a higher viral load than that observed in WT mice, we hypothesize that the liver damage and possibly the lethality observed in MDA5−/− mice are immunopathological in nature. A similar phenomenon, in which effector functions normally used to clear pathogens also damage host sites, leading to often-severe pathology, has been reported during infection with many other pathogens, including hepatitis B and C viruses (40), dengue virus (41), and Toxoplasma gondii (42). MDA5−/− mice infected with Theiler's virus generated higher levels of IL-17 and interferon gamma, both of which can contribute to pathology (9). Taken in this context, our data suggest that MDA5 may be important for negative regulation of immune responses.

We had expected to observe a difference in the T cell response between MDA5−/− and WT mice due to the elevated expression of activation markers on dendritic cells. However, by many metrics, including expression of activation markers, perforin expression, and interferon gamma expression from cells in the spleen, the T cell response was similar between genotypes. A similar observation was made during West Nile virus infection, in which the T cell response was also seemingly independent of MDA5 signaling (8). This suggests that despite elevated expression of coactivation markers by DCs, priming was largely unchanged, although elevated production of interferon gamma by T cells in the liver was observed and may be a direct result of improved priming.

We found that T cells from MDA5−/− mice had elevated expression of PD-1. PD-1/PD-L1 signaling is a driver of T cell exhaustion during chronic infections (31), but its role during acute infections is less clear. PD-1 expression correlated with a defective T cell response during West Nile virus infection (8), and PD-1 signaling was found to weaken T cell responses during acute infection with Histoplasma capsulatum (43) and rabies virus (44), suggesting that PD-1 has similar roles in acute and chronic infections. However, PD-1/PD-L1 signaling was shown to improve T cell responses during acute infection with Listeria monocytogenes (45) and influenza virus (46), indicating that it can positively regulate T cells in the context of some infections. We hypothesize that during MHV infection PD-1 expression indicates strong activation of T cells and that these T cells induce pathology in the liver, possibly accounting for the increased pathology. Jin et al. similarly found higher expression of PD-1 ligand, PD-L1, on dendritic cells during Theiler's virus infection of MDA5−/− mice than of WT mice, as well as increased pathology and elevated levels of interferon gamma and IL-17 (9), both of which can be drivers of pathology. We see no IL-17 production by T cells (data not shown) and minimal changes in production of interferon gamma, so we speculate that while the absence of MDA5 leads to immunopathology during both MHV and Theiler's virus infections, the mechanism of pathology is different for each virus.

The survival of MDA5−/− mice depleted of T cells was lower than that of mice with T cells (Fig. 8A), indicating that if the susceptibility of these mice to MHV infection is due to a lethal immunopathological response, it is not driven by T cells. We do, however, observe elevated expression of perforin by natural killer cells (Fig. 5) and increased levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interferon gamma, IL-6, and TNF-α in the sera (Fig. 8B) of MDA5−/− mice. We speculate that the low survival of MDA5−/− mice is due to an immunopathological response driven by one or more of these factors. These findings suggest a context-dependent role for MDA5 as a negative regulator of the immune response that limits immunopathology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-AI-060021 and R01-NS-054695 to S.R.W. Z.B.Z. was supported in part by training grant T32-NS007180. K.M.R. was supported by T32-AI007324 and a diversity supplement to grant R01-NS-054695.

Thanks to Helen Lazear and Michael S. Diamond, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, for MDA5−/− mice and help at early stages of the project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitoma H, Hanabuchi S, Kim T, Bao M, Zhang Z, Sugimoto N, Liu Y-J. 2013. The DHX33 RNA helicase senses cytosolic RNA and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity 39:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang D-C, Gopalkrishnan RV, Lin L, Randolph A, Valerie K, Pestka S, Fisher PB. 2004. Expression analysis and genomic characterization of human melanoma differentiation associated gene-5, mda-5: a novel type I interferon-responsive apoptosis-inducing gene. Oncogene 23:1789–1800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang D-C, Gopalkrishnan RV, Wu Q, Jankowsky E, Pyle AM, Fisher PB. 2002. mda-5: an interferon-inducible putative RNA helicase with double-stranded RNA-dependent ATPase activity and melanoma growth-suppressive properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:637–642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022637199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth-Cross JK, Bender SJ, Weiss SR. 2008. Murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus is recognized by MDA5 and induces type I interferon in brain macrophages/microglia. J Virol 82:9829–9838. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01199-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh C-S, Reis e Sousa C, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirén J, Imaizumi T, Sarkar D, Pietilä T, Noah DL, Lin R, Hiscott J, Krug RM, Fisher PB, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. 2006. Retinoic acid inducible gene-I and mda-5 are involved in influenza A virus-induced expression of antiviral cytokines. Microbes Infect 8:2013–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCartney SA, Thackray LB, Gitlin L, Gilfillan S, Virgin HW, Colonna M. 2008. MDA-5 recognition of a murine norovirus. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000108. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazear HM, Pinto AK, Ramos HJ, Vick SC, Shrestha B, Suthar MS, Gale M, Diamond MS. 2013. Pattern recognition receptor MDA5 modulates CD8+ T cell-dependent clearance of West Nile virus from the central nervous system. J Virol 87:11401–11415. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01403-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin YH, Kim SJ, So EY, Meng L, Colonna M, Kim BS. 2012. Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is critical for protection against Theiler's virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol 86:1531–1543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06457-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss SR, Leibowitz JL. 2011. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv Virus Res 81:85–164. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385885-6.00009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavi E, Gilden DH, Wroblewska Z, Rorke LB, Weiss SR. 1984. Experimental demyelination produced by the A59 strain of mouse hepatitis virus. Neurology 34:597–603. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bender SJ, Phillips JM, Scott EP, Weiss SR. 2010. Murine coronavirus receptors are differentially expressed in the central nervous system and play virus strain-dependent roles in neuronal spread. J Virol 84:11030–11044. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02688-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervantes-Barragan L, Züst R, Weber F, Spiegel M, Lang KS, Akira S, Thiel V, Ludewig B. 2007. Control of coronavirus infection through plasmacytoid dendritic-cell-derived type I interferon. Blood 109:1131–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacNamara KC, Chua MM, Nelson PT, Shen H, Weiss SR. 2005. Increased epitope-specific CD8+ T cells prevent murine coronavirus spread to the spinal cord and subsequent demyelination. J Virol 79:3370–3381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3370-3381.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips JJ, Chua MM, Lavi E, Weiss SR. 1999. Pathogenesis of chimeric MHV4/MHV-A59 recombinant viruses: the murine coronavirus spike protein is a major determinant of neurovirulence. J Virol 73:7752–7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hingley ST, Gombold JL, Lavi E, Weiss SR. 1994. MHV-A59 fusion mutants are attenuated and display altered hepatotropism. Virology 200:1–10. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavi E, Gilden DH, Highkin MK, Weiss SR. 1986. The organ tropism of mouse hepatitis virus A59 in mice is dependent on dose and route of inoculation. Lab Anim Sci 36:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navas S, Seo SH, Chua MM, Sarma JD, Lavi E, Hingley ST, Weiss SR. 2001. Murine coronavirus spike protein determines the ability of the virus to replicate in the liver and cause hepatitis. J Virol 75:2452–2457. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2452-2457.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navas S, Weiss SR. 2003. Murine coronavirus-induced hepatitis: JHM genetic background eliminates A59 spike-determined hepatotropism. J Virol 77:4972–4978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4972-4978.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudd CE, Taylor A, Schneider H. 2009. CD28 and CTLA-4 coreceptor expression and signal transduction. Immunol Rev 229:12–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueda H, Howson JMM, Esposito L, Heward J, Snook H, Chamberlain G, Rainbow DB, Hunter KMD, Smith AN, Di Genova G, Herr MH, Dahlman I, Payne F, Smyth D, Lowe C, Twells RCJ, Howlett S, Healy B, Nutland S, Rance HE, Everett V, Smink LJ, Lam AC, Cordell HJ, Walker NM, Bordin C, Hulme J, Motzo C, Cucca F, Hess JF, Metzker ML, Rogers J, Gregory S, Allahabadia A, Nithiyananthan R, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Tuomilehto J, Bingley P, Gillespie KM, Undlien DE, Rønningen KS, Guja C, Ionescu-Tîrgovişte C, Savage DA, Maxwell AP, Carson DJ, Patterson CC, Franklyn JA, Clayton DG, Peterson LB, Wicker LS, Todd JA, Gough SCL. 2003. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 423:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novais FO, Carvalho LP, Graff JW, Beiting DP, Ruthel G, Roos DS, Betts MR, Goldschmidt MH, Wilson ME, de Oliveira CI, Scott P. 2013. Cytotoxic T cells mediate pathology and metastasis in cutaneous leishmaniasis. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003504. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebhard JR, Perry CM, Harkins S, T LANE, I Mena, Asensio VC, Campbell IL, Whitton JL. 1998. Coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis: perforin exacerbates disease, but plays no detectable role in virus clearance. Am J Pathol 153:417–428. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65585-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amrani A, Verdaguer J, Anderson B, Utsugi T, Bou S, Santamaria P. 1999. Perforin-independent beta-cell destruction by diabetogenic CD8(+) T lymphocytes in transgenic nonobese diabetic mice. J Clin Invest 103:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kägi D, Odermatt B, Seiler P, Zinkernagel RM, Mak TW, Hengartner H. 1997. Reduced incidence and delayed onset of diabetes in perforin-deficient nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med 186:989–997. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergmann CC, Lane TE, Stohlman SA. 2006. Coronavirus infection of the central nervous system: host–virus stand-off. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin MT, Hinton DR, Marten NW, Bergmann CC, Stohlman SA. 1999. Antibody prevents virus reactivation within the central nervous system. J Immunol 162:7358–7368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishna C, Stohlman SA, Atkinson RD, Shlomchik MJ, Bergmann CC. 2002. Mechanisms of central nervous system viral persistence: the critical role of antibody and B cells. J Immunol 168:1204–1211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro RF, Perlman S. 1995. CD8+ T-cell epitopes within the surface glycoprotein of a neurotropic coronavirus and correlation with pathogenicity. J Virol 69:8127–8131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue S, Jaszewski A, Perlman S. 1995. Identification of a CD4+ T cell epitope within the M protein of a neurotropic coronavirus. Virology 208:173–179. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown KE, Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ, Sharpe AH. 2010. Role of PD-1 in regulating acute infections. Curr Opin Immunol 22:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ireland DDC, Stohlman SA, Hinton DR, Atkinson R, Bergmann CC. 2008. Type I interferons are essential in controlling neurotropic coronavirus infection irrespective of functional CD8 T cells. J Virol 82:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01794-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loo Y-M, Fornek J, Crochet N, Bajwa G, Perwitasari O, Martinez-Sobrido L, Akira S, Gill MA, García-Sastre A, Katze MG, Gale M. 2008. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J Virol 82:335–345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem 67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. 2005. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J Immunol 174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. 2005. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med 202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Bon A, Schiavoni G, D'Agostino G, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Tough DF. 2001. Type I interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and can promote isotype switching by stimulating dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity 14:461–470. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFadden G, Mohamed MR, Rahman MM, Bartee E. 2009. Cytokine determinants of viral tropism. Nat Rev Immunol 9:645–655. doi: 10.1038/nri2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zignego AL, Piluso A, Giannini C. 2008. HBV and HCV chronic infection: autoimmune manifestations and lymphoproliferation. Autoimmun Rev 8:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurane I, Ennis FE. 1992. Immunity and immunopathology in dengue virus infections. Semin Immunol 4:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israelski DM, Araujo FG, Conley FK, Suzuki Y, Sharma S, Remington JS. 1989. Treatment with anti-L3T4 (CD4) monoclonal antibody reduces the inflammatory response in toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Immunol 142:954–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lázár-Molnár E, Gácser A, Freeman GJ, Almo SC, Nathenson SG, Nosanchuk JD. 2008. The PD-1/PD-L costimulatory pathway critically affects host resistance to the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:2658–2663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711918105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lafon M, Mégret F, Meuth SG, Simon O, Velandia Romero ML, Lafage M, Chen L, Alexopoulou L, Flavell RA, Prehaud C, Wiendl H. 2008. Detrimental contribution of the immuno-inhibitor B7-H1 to rabies virus encephalitis. J Immunol 180:7506–7515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe JH, Johanns TM, Ertelt JM, Way SS. 2008. PDL-1 blockade impedes T cell expansion and protective immunity primed by attenuated Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol 180:7553–7557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talay O, Shen C-H, Chen L, Chen J. 2009. B7-H1 (PD-L1) on T cells is required for T-cell-mediated conditioning of dendritic cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:2741–2746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]