Abstract

Neuroblastoma is an aggressive solid tumor that leads to tumor relapse in more than half of high-risk patients. Minimal residual disease (MRD) is primarily responsible for tumor relapses and may be detected in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) samples. To evaluate the disease status and treatment response, a number of MRD detection protocols based on either common or distinct markers for PB and BM samples have been reported. However, the correlation between the expression of MRD markers in PB and BM samples remains elusive in the clinical samples. In the present study, the expression of 11 previously validated MRD markers (CHRNA3, CRMP1, DBH, DCX, DDC, GABRB3, GAP43, ISL1, KIF1A, PHOX2B and TH) was determined in 23 pairs of PB and BM samples collected from seven high-risk neuroblastoma patients at the same time point, and the sample was scored as MRD-positive if one of the MRD markers exceeded the normal range. Although the number of MRD-positive samples was not significantly different between PB and BM samples, the two most sensitive markers for PB samples (CRMP1 and KIF1A) were different from those for BM samples (PHOX2B and DBH). There was no statistically significant correlation between the expression of MRD markers in the PB and BM samples. These results suggest that MRD markers were differentially expressed in PB and BM samples from high-risk neuroblastoma patients.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, minimal residual disease, peripheral blood, bone marrow

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most frequent extracranial solid tumor in children and is characterized by its extreme heterogeneity, ranging from spontaneous regression to malignant progression. More than half of neuroblastoma patients are stratified into a high-risk group and <40% of these high-risk patients can expect long-term survival. This is mainly due to the chemoresistant minimal residual disease (MRD) that is primarily responsible for tumor metastasis and relapse (1–3).

Although tumor cell dissemination is traditionally classified as a late event during tumor progression, accumulating evidence suggests that tumor cells disseminate from the primary lesions even before the formation of overt tumors, and become circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the peripheral blood (PB) and disseminating tumor cells (DTCs) in the bone marrow (BM) (4–6). Following local and systemic treatment, residual tumor cells remain as CTCs in the PB and DTCs in the BM, as well as cancer stem cells in the primary lesions. Due to the extremely restricted availability of primary tumor samples, PB and BM samples are mainly used for MRD monitoring in the clinics (7–9).

As sensitive detection of MRD is essential for monitoring disease status and evaluating treatment response in high-risk neuroblastoma patients, a number of MRD detection protocols based on reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) markers have been reported (10–13). Although the ideal markers should be exclusively expressed in neuroblastoma cells, the currently available markers are selected by their ability to define a cut-off value that distinguishes neuroblastoma cells from normal PB and BM cells.

To overcome this limitation, the current protocols utilize multiple MRD markers for PB and BM samples, which are either common or distinct. Common MRD markers are reported as three-marker [double-cortin (DCX), paired-like homeobox 2b (PHOX2B) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)] and eight-marker [(cyclin D1, collapsin response mediator protein 1 (CRMP1), dopa decarboxylase (DDC), GABA A receptor β3 (GABRB3), ISL LIM homeobox 1 (ISL1), kinesin family member 1A (KIF1A), PHOX2B and transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 2] sets (10,11), while distinct MRD markers are reported as the PB set [PHOX2B, TH, DDC, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) and cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α3 (CHRNA3)] and BM set [(PHOX2B, TH, DDC, CHRNA3 and growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43)] (12). However, the rationale for introducing the current protocols into the clinics remains unclear (14–16).

In the present study, we determined the expression of 11 previously validated MRD markers (CHRNA3, CRMP1, DBH, DCX, DDC, GABRB3, GAP43, ISL1, KIF1A, PHOX2B and TH) in 23 pairs of PB and BM samples collected from seven high-risk neuroblastoma patients treated at Kobe University Hospital and Kobe Children's Hospital, Japan, between November 2011 and April 2014 (13), and analyzed the correlation between PB and BM samples.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

All PB and BM samples were obtained from seven high-risk neuroblastoma patients with written informed consent. All patients were treated at Kobe University Hospital and Kobe Children's Hospital between November 2011 and April 2014. The use of human samples for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine and conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Clinical Research of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

All PB and BM samples were separated using Mono-Poly resolving medium (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan), and nucleated cells were collected according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was then extracted with a TRIzol Plus RNA purification kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After evaluating RNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis, cDNA was synthesized from 1 or 0.5 µg total RNA using a Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and diluted to a total volume of 80 or 40 µl.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a total volume of 15 µl consisting of 7.5 µl 2X FastStart Universal SYBR-Green Master (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 1.5 µl each of 3 µM sense and anti-sense primers, and 1 µl sample cDNA (corresponding to 12.5 ng total RNA). Each cDNA was amplified with a precycling hold at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec, and one cycle at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec, 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 15 sec. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The expression of the 11 MRD markers (CHRNA3, CRMP1, DBH, DCX, DDC, GABRB3, GAP43, ISL1, KIF1A, PHOX2B and TH) was calculated based on the relative standard curve method using β2-microglobulin as an endogenous reference for normalization, and was scored as positive if its expression exceeded the normal range (13).

Statistical analysis

Differences between the number of MRD-positive samples in PB and BM were evaluated by McNemar's Chi-squared test. To assess the correlation between MRD marker expression in PB and BM samples, the expression of each marker was ranked according to the number of positive samples in 23 PB and 23 BM samples. Correlation between the rank in PB and BM samples was assessed by Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed with EZR (version 1.24 www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmedEN.html; Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) (17).

Results

Characteristics of PB and BM samples

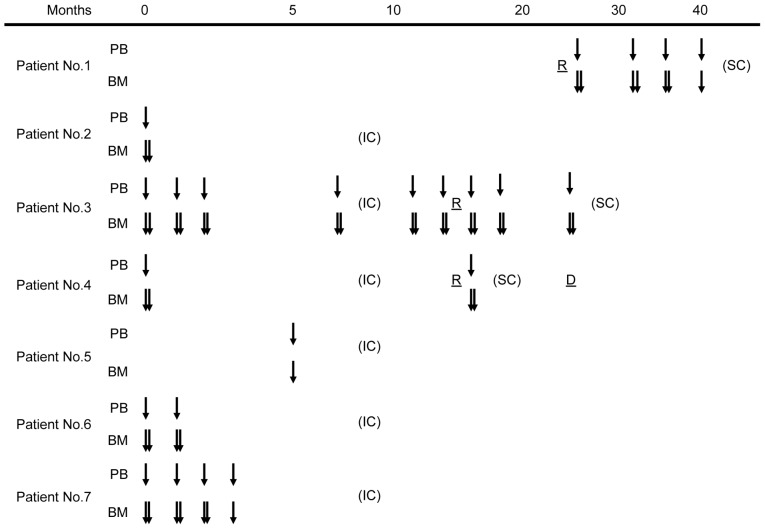

The 23 pairs of PB and BM samples were obtained at the same time point from seven high-risk neuroblastoma patients who were treated at Kobe University Hospital and Kobe Children's Hospital between November 2011 and April 2014 (Fig. 1). Patient characteristics are shown in Table I. All patients were stratified into the high-risk group (18) and treated with induction chemotherapy followed by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, radiation therapy and surgical therapy according to the Japan Neuroblastoma Study Group protocol. Patients 1, 3 and 4 experienced tumor relapse and underwent salvage chemotherapy. The median follow-up time was 24 months (range, 7–29 months).

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) sample characteristics. Downward arrows indicate the time points of minimal residual disease sampling. Month 0 was defined as the time when the primary tumor was diagnosed. IC, induction chemotherapy; SC, salvage chemotherapy; R, tumor relapse.

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient number | Age | Gender | Tumor origin | INSS stage | MYCN status | Follow-up | Present status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 y | M | Adrenal gland | 4 | Non-amplified | 25–49 m | Alive (Relapsed) |

| 2 | 4 y | M | Adrenal gland | 3 | Non-amplified | 0–29 m | Alive (Relapse-free) |

| 3 | 2 y | M | Adrenal gland | 4 | Amplified | 0–24 m | Alive (Relapsed) |

| 4 | 3 y | F | Adrenal gland | 4 | Amplified | 0–24 m | Deceased (Relapsed) |

| 5 | 5 y | M | Posterior mediastinum | 4 | Non-amplified | 0–17 m | Alive (Relapse-free) |

| 6 | 11 m | M | Adrenal gland | 4 | Amplified | 0–9 m | Alive (Relapse-free) |

| 7 | 14 m | M | Adrenal gland | 4 | Amplified | 0–7 m | Alive (Relapse-free) |

y, years; m, months; M, male; F, female; INSS, International Neuroblastoma Staging System; MYCN, v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma-derived homolog.

CHRNA3, CRMP1, DBH, DCX, DDC, GABRB3, GAP43, ISL1, KIF1A, PHOX2B and TH expression was determined by RT-qPCR, and was scored as positive if its expression exceeded the normal range (13). The number of positive MRD markers in each sample is presented in Table II. A sample was scored as MRD-positive if it had more than one positive marker. There was no statistically significant difference between the number of MRD-positive samples in PB and BM samples (Table III, P=1.000).

Table II.

Sample characteristics.

| Number of positive markers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sample pair number | PB sample | BM sample |

| 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 0 | 9 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 11 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | 2 | 11 |

| 13 | 6 | 11 |

| 14 | 2 | 11 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | 10 | 11 |

| 17 | 0 | 1 |

| 18 | 0 | 1 |

| 19 | 2 | 1 |

| 20 | 0 | 10 |

| 21 | 1 | 7 |

| 22 | 1 | 0 |

| 23 | 0 | 0 |

PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow.

Table III.

MRD monitoring in PB and BM samples.

| BM sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| PB sample | MRD (+) | MRD (−) |

| MRD (+) | 11 | 4 |

| MRD (−) | 5 | 3 |

MRD, minimal residual disease; PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow.

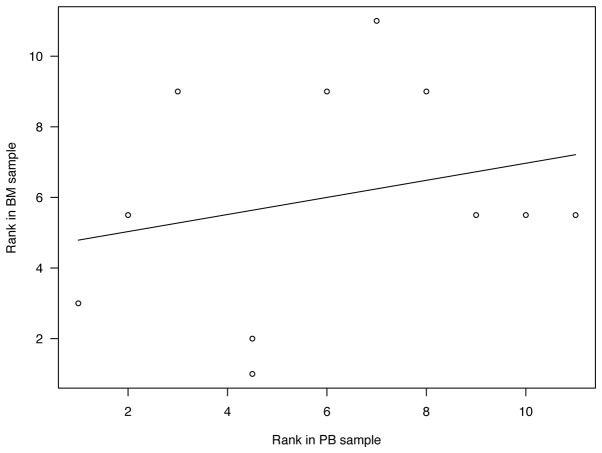

Correlation between MRD marker expression in PB and BM samples

The number of positive samples of each MRD marker in PB and BM samples is shown in Table IV. CRMP1 and KIF1A were ranked as the two most sensitive markers for PB samples, whereas these were PHOX2B and DBH for BM samples. There was no statistical significance in the correlation between the rank of MRD markers in PB and BM samples (Fig. 2, r=0.250, P=0.459).

Table IV.

MRD marker expression in PB and BM samples.

| MRD marker | PB sample | BM sample |

|---|---|---|

| CHRNA3 | ||

| (+) | 1 | 9 |

| (−) | 20 | 14 |

| CRMP1 | ||

| (+) | 9 | 10 |

| (−) | 14 | 13 |

| DBH | ||

| (+) | 3 | 12 |

| (−) | 20 | 11 |

| DCX | ||

| (+) | 4 | 8 |

| (−) | 19 | 15 |

| DDC | ||

| (+) | 1 | 9 |

| (−) | 22 | 14 |

| GABRB3 | ||

| (+) | 2 | 5 |

| (−) | 21 | 18 |

| GAP43 | ||

| (+) | 2 | 8 |

| (−) | 19 | 15 |

| ISL1 | ||

| (+) | 1 | 8 |

| (−) | 19 | 15 |

| KIF1A | ||

| (+) | 6 | 9 |

| (−) | 17 | 14 |

| PHOX2B | ||

| (+) | 3 | 13 |

| (−) | 20 | 10 |

| TH | ||

| (+) | 1 | 9 |

| (−) | 22 | 14 |

MRD, minimal residual disease; PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; CHRNA3, cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α3; CRMP1, collapsin response mediator protein 1; DBH, dopamine β-hydroxylase; DCX, double-cortin; DDC, dopa decarboxylase; GABRB3, GABA A receptor β3; GAP43, growth-associated protein 43; ISL1, ISL LIM homeobox 1; KIF1A, kinesin family member 1A; PHOX2B, paired-like homeobox 2b; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase.

Figure 2.

Correlation between minimal residual disease (MRD) marker expression in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) samples. The expression of each MRD marker was ranked according to the number of positive samples in 23 PB and 23 BM samples. Correlation between the rank in PB and BM samples was analyzed by Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Discussion

To improve the outcome of high-risk neuroblastoma patients, sensitive MRD detection is essential for evaluating the disease status and treatment response. Although MRD may be detected in PB as well as BM samples, the correlation of MRD marker expression between the PB and BM samples remains elusive. In the present study, we determined the expression of 11 previously validated MRD markers (CHRNA3, CRMP1, DBH, DCX, DDC, GABRB3, GAP43, ISL1, KIF1A, PHOX2B and TH) in 23 pairs of PB and BM samples obtained from seven high-risk neuroblastoma patients treated at Kobe University Hospital and Kobe Children's Hospital between November 2011 and April 2014 (13). Although the number of MRD-positive samples was not significantly different between PB and BM samples, there was no significant correlation between the expression of these markers in the samples.

In the present study, we collected the 23 pairs of PB and BM samples from the same patient at the same time point in order to minimize the variability of MRD marker expression (19). Even under these conditions, the sensitivity of MRD markers in PB samples was clearly different from that in BM samples (Table IV). KIF1A and DCX were the only positive markers in PB but not BM samples, whereas PHOX2B and DBH were positive in BM but not PB samples. Although DBH was previously listed as an MRD marker for PB samples (12), the present study identified it as being one of the most sensitive markers in BM samples. As suggested for anti-GD2 antibody and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) therapies (11), the various treatment protocols might affect these inconsistencies.

Although the quantity of MRD in PB and/or BM samples predicts tumor relapse and patient outcome, conflicting results have been reported with regard to the prognostic value of MRD monitoring using various MRD markers (14–16). Given that CTCs in the PB and DTCs in the BM define the main faces of MRD in the clinics, these inconsistencies may imply genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of CTCs and DTCs (20–22). Although CTCs have not been convincingly isolated from neuroblastoma patients, as demonstrated in breast and lung cancers (23,24), the present results reveal the need for careful selection of MRD markers for PB and BM samples.

In summary, the expression of 11 previously validated MRD markers in PB and BM samples from high-risk neuroblastoma patients was not significantly correlated. Distinct markers for PB and BM samples may be required to achieve sensitive MRD detection in neuroblastoma patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and grants from the Children's Cancer Association of Japan and Hyogo Science and Technology Association.

References

- 1.Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: Biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–2120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hüsemann Y, Geigl JB, Schubert F, Musiani P, Meyer M, Burghart E, Forni G, Eils R, Fehm T, Riethmüller G, Klein CA. Systemic spread is an early step in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang Y, Pantel K. Tumor cell dissemination: Emerging biological insights from animal models and cancer patients. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller V, Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Insights into minimal residual disease in cancer patients: Implications for anti-cancer therapies. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin H, Balic M, Zheng S, Datar R, Cote RJ. Disseminated and circulating tumor cells: Role in effective cancer management. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mordant P, Loriot Y, Lahon B, Castier Y, Lesèche G, Soria JC, Massard C, Deutsch E. Minimal residual disease in solid neoplasia: New frontier or red-herring? Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viprey VF, Lastowska MA, Corrias MV, Swerts K, Jackson MS, Burchill SA. Minimal disease monitoring by QRT-PCR: guidelines for identification and systematic validation of molecular markers prior to evaluation in prospective clinical trials. J Pathol. 2008;216:245–252. doi: 10.1002/path.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung IY, Feng Y, Gerald W, Cheung NK. Exploiting gene expression profiling to identify novel minimal residual disease markers of neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7020–7027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stutterheim J, Gerritsen A, Zappeij-Kannegieter L, Yalcin B, Dee R, van Noesel MM, Berthold F, Versteeg R, Caron HN, van der Schoot CE, Tytgat GA. Detecting minimal residual disease in neuroblastoma: The superiority of a panel of real-time quantitative PCR markers. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1316–1326. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartomo TB, Kozaki A, Hasegawa D, Van Huyen Pham T, Yamamoto N, Saitoh A, Ishida T, Kawasaki K, Kosaka Y, Ohashi H, et al. Minimal residual disease monitoring in neuroblastoma patients based on the expression of a set of real-time RT-PCR markers in tumor-initiating cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1629–1636. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stutterheim J, Zappeij-Kannegieter L, Versteeg R, Caron HN, van der Schoot CE, Tytgat GA. The prognostic value of fast molecular response of marrow disease in patients aged over 1 year with stage 4 neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yáñez Y, Grau E, Oltra S, Cañete A, Martínez F, Orellana C, Noguera R, Palanca S, Castel V. Minimal disease detection in peripheral blood and bone marrow from patients with non-metastatic neuroblastoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1263–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-0997-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrias MV, Haupt R, Carlini B, Cappelli E, Giardino S, Tripodi G, Tonini GP, Garaventa A, Pistoia V, Pistorio A. Multiple target molecular monitoring of bone marrow and peripheral blood samples from patients with localized neuroblastoma and healthy donors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:43–49. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castleberry RP, Pritchard J, Ambros P, Berthold F, Brodeur GM, Castel V, Cohn SL, De Bernardi B, Dicks-Mireaux C, Frappaz D, et al. The international neuroblastoma risk groups (INRG): a preliminary report. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2113–2116. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stutterheim J, Zappeij-Kannegieter L, Ora I, van Sluis PG, Bras J, den Ouden E, Versteeg R, Caron HN, van der Schoot CE, Tytgat GA. Stability of PCR targets for monitoring minimal residual disease in neuroblastoma. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermeulen L, de Sousa e Melo F, Richel DJ, Medema JP. The developing cancer stem-cell model: clinical challenges and opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e83–e89. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Cancer: Circulating tumor cells. Science. 2013;341:1186–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1235226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Challenges in circulating tumour cell research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:623–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baccelli I, Schneeweiss A, Riethdorf S, Stenzinger A, Schillert A, Vogel V, Klein C, Saini M, Bäuerle T, Wallwiener M, et al. Identification of a population of blood circulating tumor cells from breast cancer patients that initiates metastasis in a xenograft assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:539–544. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodgkinson CL, Morrow CJ, Li Y, Metcalf RL, Rothwell DG, Trapani F, Polanski R, Burt DJ, Simpson KL, Morris K, et al. Tumorigenicity and genetic profiling of circulating tumor cells in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nm.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]