Abstract

Objective

The interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior emphasizes the constructs of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capacity, which warrant investigation in adolescents at-risk for suicide due to interpersonal stressors.

Methods

This study examined one component of the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior, “suicidal desire” (suicidal ideation), in 129 adolescents (12–15 years) recruited from a general medical emergency department who screened positive for bully victimization, bully perpetration, or low interpersonal connectedness.

Results

Greater perceived burdensomeness combined with low family connectedness was a significant predictor of suicidal ideation.

Conclusion

This suggests the importance of addressing connectedness and perceptions of burdensomeness in prevention and early intervention efforts with at-risk adolescents.

Keywords: interpersonal theory of suicidal behaviors, perceived burdensomeness, connectedness, adolescents, suicidal ideation

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). Before the age of 10, less than 1% of youth report suicidal ideation; however, early in adolescence (approximately the age of 12), significant increases in suicidal thoughts are found and become more prevalent as the adolescent ages (Nock et al., 2013).

Adolescent interpersonal problems with family, peers, and community are among the widely established risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (e.g., Czyz, Liu, & King, 2012; King & Merchant, 2008). More specifically, bully victimization and bully perpetration have been found to be associated with increased levels of suicidal ideation and attempts. In a sample of 2,088 Norwegian 8th graders, mean scores of suicidal ideation in both bullies and victims were higher than scores among non-bullied adolescents (Roland, 2002). Similarly, in a U.S. national sample of over 11,940 students in grades 7–12, Russell and Joyner (2001) showed that adolescent bully victims were more likely to express suicidal thoughts and attempt suicide, even after controlling for sexual orientation, depression, hopelessness, alcohol abuse, and history of suicide attempts made by family and friends. Additionally, low social support has been found to be associated with suicidal ideation in adolescents living in a community characterized by high poverty and unemployment rates (Logan, Crosby, & Hamburger, 2011). Kerr, Preuss, and King (2006) reported that low levels of social support are associated with a variety of suicide-related risk factors, such as alcohol/substance problems, hopelessness, and depression.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of interpersonal problems among adolescents is greater than one might expect. Nansel and colleagues (2001), analyzing a nationally representative sample of 15,686 U.S. students in grades 6 through 10, found that 29.9% of students reported involvement in moderate to frequent bullying during a single term. Of those who reported such behavior, 10.6% were victims of bullying, 13.0% were perpetrators of bullying, and 6.3% reported engaging in both types of behaviors. Additionally, prevalence rates of low social support in adolescents range from about 20–30% (Gecková, Van Dijk, Stewart, Groothoff, & Post, 2003; Wight, Botticello, & Aneshensel, 2006). An improved understanding of factors that can account for the association between interpersonal problems and adolescent suicidal ideation may inform suicide prevention efforts. In this study, we examine a promising theory of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005), as a means of explaining the variability in suicidal ideation among adolescents at risk for suicide due to interpersonal problems (i.e., bully victimization, bully perpetration, low interpersonal connectedness).

Interpersonal Theory of Suicidal Behavior

The interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) proposes that suicidal behavior takes place when an individual has both the desire for suicide, which results from thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and an acquired capacity to enact lethal self-injury. One conceptualization for a desire for suicide is suicidal ideation (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Thwarted belongingness is a sense of feeling disconnected or alienated from others while burdensomeness reflects a perception that one is a burden on others; a person’s sense of burdensomeness may be reflected in feelings that one’s death will be worth more than one’s life to family, friends, or society (Joiner et al., 2009). The third component, the acquired capacity for suicide, is described as fearlessness about physical pain and death itself, acquired through risky behaviors or painful and provocative experiences that habituate a person toward self-injury and suicidal behaviors. Suicide risk factors, such as major depressive disorder and family history of suicide, are hypothesized to be associated with suicidal thoughts when they involve feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and, if further combined with acquired capacity, may lead to suicidal behavior (Van Orden et al., 2010). The theory thus far has been examined in adult and college student samples. Although there is no existing literature with adolescent samples, the underlying principles have been theorized to be consistent across the lifespan (Joiner, 2005). Van Orden and colleagues (2008) found that the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness was associated with current suicidal ideation in college students. Similarly, Joiner and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that low family social support together with feelings of not mattering were associated with suicidal ideation among young adults. Moreover, the interaction between all three components of the theory, with acquired capacity measured by lifetime number of suicide attempts, predicted suicide attempts in a clinical sample of suicidal young adults (Joiner et al., 2009).

The goal of the present study is to examine the suicidal desire (i.e., suicidal ideation) component of the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior among at-risk adolescents with interpersonal problems. More specifically, we focus on the two components of the theory that are thought to lead to suicidal ideation – thwarted belongingness (connectedness) and perceived burdensomeness.

Connectedness and suicidal ideation

Social connectedness is a key aspect of thwarted belongingness (Van Orden et al., 2010). In this study, we had a unique opportunity to examine family, school, and peer connectedness, which research has shown can serve as protective factors against suicide-related outcomes, including suicidal ideation and attempts. In a nationally representative sample of 12,118 adolescents, Resnick and colleagues (1997) found that greater levels of family and school connectedness were both negatively associated with suicidal ideation/attempts. In a study of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents, improvements in family connectedness following hospitalization were associated with less severe suicidal ideation during the entire year following hospitalization; however, this protective effect extended only to adolescents without histories of multiple suicide attempts (Czyz et al., 2012). In the same study, adolescents reporting greater post-hospitalization peer connectedness were half as likely to attempt suicide during the 12-month follow-up period.

Burdensomeness

While the association between connectedness and suicide-related outcomes has received more research attention, much less is known about perceived burdensomeness, the second component of the theory. The few existing studies that examined perceived burdensomeness have shown that it is associated with higher suicide risk. In a study of suicide notes, the notes of those who died by suicide were found to contain more perceived burdensomeness compared to the notes of those who survived their suicide attempts (Joiner et al., 2002). In a study involving adult outpatients, perceived burdensomeness was also associated with current suicidal ideation and past number of suicide attempts; importantly, this effect was significant even after controlling for hopelessness (Van Orden, Lynam, Hollar, & Joiner, 2006).

Little is known, however, about the impact of burdensomeness on adolescent suicidal ideation and behavior. To the best of our knowledge, there is one study that examined a construct similar to perceived burdensomeness – namely, feeling expendable within one’s family (Woznica & Shapiro, 1990). Woznica and Shapiro (1990) studied the “expendable child” syndrome, originally proposed by Sabbath (1969), in the context of suicide attempts. These authors found that higher scores on a psychotherapist-rated scale of expendability, or a sense of being unwanted and/or a burden on their families, differentiated adolescents with suicidal ideation or history of attempts from other adolescents. An important limitation of this study, however, is that psychotherapists, as opposed to the adolescents themselves, rated these adolescents’ sense of expendability as well as their suicidal ideation. Moreover, it is possible that one’s sense of expendability or burdensomeness could be fueled by experiences outside of the family. This may be particularly relevant for adolescents who are bullied, experience rejection by their peers, and/or have low interpersonal connectedness.

Study Aim

Based on the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005) and its constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether the presence of low social connectedness (thwarted belongingness) in combination with high perceived burdensomeness was a stronger predictor of suicidal ideation than either construct alone. Social connectedness, which maps onto thwarted belongingness (Van Orden et al., 2010), encompasses different domains of connectedness. Therefore, we hypothesized that independently examining the social connectedness domains of family, school, and peer relationships, when paired with perceived burdensomeness, would yield significant associations with suicidal ideation, in line with the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior. We examined whether these relationships were significant over and above important covariates of suicidal ideation, including sex (e.g., Roland, 2002), bully victimization and perpetration (e.g., Brunstein-Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould, 2007), and depression (e.g., Hawton, Casañas i Comabella, Haw, & Saunders, 2013). Given this study’s focus on at-risk adolescents due to self-reported interpersonal problems in the context of peer relationships (i.e bullying), a consideration of peer and school connectedness is especially important.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from consecutive admissions (during afternoon/evening recruitment shifts) at an urban medical ED in the Midwestern region of the United States, with a consent rate of 79.6%. ED admissions were for general medical (e.g., broken bones; fever; sports injuries) and psychiatric concerns (e.g., behavioral and/or emotional problems).This study’s sample was drawn from a larger CDC-funded intervention effectiveness trial, Links to Enhancing Teens’ Connectedness (LET’s CONNECT), led by one of the co-authors (C.A. King). LET’s CONNECT was designed to prevent the onset of suicidal behavior in adolescents at elevated risk for suicidal behavior. This study employed the following inclusion criteria: (1) ages 12–15 years, (2) English speaking, (3) residence within a defined geographical area, and (4) positive screen due to self-reported peer victimization (as the victim or bully perpetrator) and/or low interpersonal connectedness. Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of suicide attempt, (2) severe cognitive impairment, (3) patient in police custody or resides in residential facility, or (4) participation in another study. Participants who presented to the emergency department (ED) for a suicide attempt were excluded from the study and all participants completed a questionnaire that asked if they have ever made a suicide attempt or done anything as a way to end their life. A total of 636 adolescents (56% female), ages 12 to 15 (M = 13.49, SD = 1.10) were screened as part of the LET’s CONNECT study.

The present study includes 129 adolescents from this parent study (66.7% female), ages 12 to 15 years (M = 13.67, SD = 1.09) who screened positive for bully victimization (68.2%), bully perpetration (19.4%), and/or low interpersonal connectedness (58.9%). The Peer Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001) was used to screen for bully victimization and/or perpetration by using a cutoff score of greater than or equal to one standard deviation above the mean, based on previously published data from a sample of 7th to 9th grade adolescents (Vernberg, Jacobs, & Hershberger, 1999). Low interpersonal connectedness was measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale (D. Russell, Peplau, & Curtrona, 1980; D. Russell, Peplau, & Ferguson, 1978). A cutoff score, based off of a community sample of adolescents, of greater than or equal to one standard deviation above the mean was used to define a positive screen (Pretty, Andrews, & Collet, 1994).

The distribution of adolescent participants’ self-identified racial identity and ethnicity was as follows: 80 African American/Black (62.0%), 56 Caucasian (43.4%), six American Indian/Alaskan Native (4.7%), one Asian (0.8%), and one “Other” (0.8%). Participants were able to choose more than one race. A total of nine participants (7.0%) described their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino. The education of participants’ biological mother’s/stepmother’s was primarily at a high school graduate or some college or technical school level (69.0%); 16.3% were at or above a college graduate level; 13.2% of participants’ mothers did not graduate from high school; and 1.6% did not know the mother’s/stepmother’s education level. A majority of the biological father’s/stepfather’s had graduated from high school or attended some college or technical school (57.4%); 19.4% did not graduate from high school; 14.0% did not know the father’s/stepfather’s education level; 8.5% were at or above a college graduate level; and 0.1% did not respond. A large proportion of families (82.9%) were receiving public assistance.

Measures

Peer Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ; Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg et al., 1999) is composed of two, nine-item scales, Victimization of Self (VS; bully victimization) and Victimization of Others (VO; bully perpetration) that measures relational and overt aggressive behaviors. Participants were asked to take into consideration the past four months when responding. Each scale measures the same nine events; however, directions indicate to respond if these events have happened to respondents or if they have done them to others. The PEQ has demonstrated high internal consistency for VS (α = 0.78) and VO (α = 0.85) scales in a sample of 7–9th grade students (Vernberg et al., 1999). Sample items include, “Teased in a mean way,” “Left out of something you wanted to do,” and “Hit, kicked, or pushed in a mean way.” Response choices are on a 5-point Likert scale (never, once or twice, a few times, about once a week, several times a week). In the current sample, internal consistency coefficients for VS and VO were α = 0.76 and α = 0.83, respectively.

UCLA Loneliness Scale-Revised (D. Russell et al., 1980; D. Russell et al., 1978) measures self-reported levels of loneliness, low connectedness, and social isolation. This 20-item measure utilizes a four-point Likert scale ranging from “I have felt this way often” to “I have never felt this way.” Good internal consistency has been found in adolescent samples, ranging from α = .81 to .89 (Mahon & Yarcheski, 1990; Mahon, Yarcheski, & Yarcheski, 1995). Additionally, support for concurrent and discriminant validity has been found in college student samples (D. Russell et al., 1980). Example items include: “There are people I can turn to,” and “I feel part of a group of friends [reverse coded].” An internal consistency coefficient of .79 was found in the current sample.

Parent-Family Connectedness (Resnick et al., 1997) is a self-report measure of the individual’s current connectedness to their parents and family using an 11-item, 5-point Likert scale (ranging from not at all to very much). Example items include, “How much do people in your family understand you” and “How much do you and your family have fun together.” Good internal consistency (α = 0.83) has been found for this measure in 7–12th grade students, irrespective of sex or racial affiliation (Sieving et al., 2001). An internal consistency of α = 0.88 was found in the current sample.

School Connectedness (Resnick et al., 1997) is a self-report instrument measuring the individual’s current sense of school belonging. Six items, on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree), compose this scale. Sample items include, “You feel close to people at your school” and “You feel like you are part of your school.” Good internal consistency (α = 0.75) has been found across sex and race in a nationally representative sample of U.S. 7–12th grade students (Sieving et al., 2001), and internal consistency for this sample was also good (α = 0.83).

Peer Connectedness (Karcher & Sass, 2010) is the 6-item Connectedness to Friends subscale from Hemingway’s Adolescent Connectedness Scale (Karcher, 2011). Each item is measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from not at all true to very true, with the overall scale measuring adolescents’ current social support and trust in friends. Example items are, “I have friends I’m really close to and trust completely” and “Spending time with my friends is a big part of my life.” The measure has shown good internal consistency (α = 0.78) across sex and race in a sample of 6–8th grade students (Karcher & Sass, 2010). Good internal consistency was also found in this sample (α = 0.84).

Suicide Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1988) is a self-report measure that covers 15 questions aimed at assessing the frequency of suicidal thoughts over the past month. Each item is scored on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from I never had this thought to almost every day. The SIQ-JR measures the frequency of a wide range of suicidal thoughts during the past month. The measure assesses passive and general thoughts (e.g. “I thought about death,” “I thought about killing myself”), active suicidal thoughts (e.g., “I thought about how I would kill myself,” “I thought about when I would kill myself”), and suicidal thoughts within an interpersonal context (e.g. “I thought that no one cared if I lived or died”). The total score from the SIQ-JR has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Reynolds, 1988, 1992). A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89 was found in this sample.

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale, 2nd Edition-Short Form (RADS-2-SF; Reynolds, 1987), is a 10-item self-report scale measuring depressive symptoms (e.g., “I feel lonely,” “I feel like nothing I do helps any more”) on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from almost never to most of the time. Psychometric properties are akin to the RADS full scale (Reynolds, 1987) with the RADS-2-SF demonstrating good reliability and validity (Milfont et al., 2008). Internal consistency for this sample was found to be excellent (α = 0.88).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012) contains 15 items measuring recent thwarted belongingness (i.e., disconnectedness from others) and perceived burdensomeness (i.e., feeling like a burden on others), both of which are components of the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005). For the purposes of this study, only the burdensomeness subscale was utilized. Sample items include, “The people in my life would be better off if I were gone” and “I think I am a burden on society.” Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from not at all true for me to very true for me. Van Orden and colleagues (2012) determined through confirmatory factor analysis of young and older adults that the INQ is consistent with the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior for both of these age groups. However, to our knowledge, this is the first use of the INQ perceived burdensomeness subscale has been utilized in an adolescent sample. The INQ measure used in this study has a Flesch-Kincaid reading level of grade 3.7, ensuring it is appropriate for the average 12–15 year old reader. The perceived burdensomeness subscale has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.89) with undergraduate students (Van Orden et al., 2008), and was also found to have excellent psychometrics in our sample (α = 0.89).

Procedure

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study, in addition to parent/guardian written informed consent and adolescent written informed assent. Potential participants were approached in the emergency department, while in the waiting room or assigned ED room. Those who consented, were first asked to participate in a brief (< 5 minutes) screening phase (victim of bullying, perpetrator of bullying, low interpersonal connectedness) to determine their eligibility for the more comprehensive baseline evaluation of connectedness, suicidal ideation/behavior, and other areas of functioning.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all primary study variables. As shown, there were a number of significant sex differences. Female adolescents reported lower levels of family and school connectedness than males, p < .001 and p = .037, respectively. In contrast, severity of bully victimization was not found to be statistically different between males and females, p = .618, nor was bully perpetration, though it was trending, p = .06. Females reported higher levels on two of the three measured constructs of maladjustment, suicidal ideation on the SIQ-JR, p = .015 and depression on the RADS-2-SF, p = .019. No differences were found between males and females in regards to perceived burdensomeness on the INQ-R, p = .271. Primary study variables did not significantly differ by race, with p values ranging from .22 for school connectedness (F = 1.55) to .85 for family connectedness (F = 0.17). Family connectedness, school connectedness, and depression were each significantly correlated with age, with Pearson’s r coefficients of −.30, −.24, and .21, respectively. With regard to this sample’s level of suicidal ideation, 22 participants (17.1%) reported having thought about suicide at least once in the past month. Finally, 13 participants (10.1%) scored at or above the SIQ-JR clinical cutoff of 31, suggesting a referral for a suicide risk evaluation.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Overall Mean (SD) (n = 129) |

Male Mean (SD) (n = 43) |

Female Mean (SD) (n = 86) |

t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bully Victimization | 19.57 (6.20) | 19.95 (6.55) | 19.37 (6.05) | −0.50 | .618 |

| Bully Perpetration | 13.88 (5.04) | 15.19 (5.94) | 13.23 (4.42) | −1.91 | .061 |

| UCLA Loneliness | 43.31 (9.01) | 41.28 (9.17) | 44.33 (8.81) | 1.83 | .070 |

| Connectedness | |||||

| Family | 39.74 (9.56) | 44.95 (8.27) | 37.14 (9.13) | −4.73 | <.001 |

| School | 20.36 (5.70) | 21.86 (5.62) | 19.63 (5.62) | −2.11 | .037 |

| Peer | 21.16 (6.00) | 21.12 (6.24) | 21.19 (5.91) | 0.06 | .951 |

| Perceived Burdensomeness | 13.35 (8.50) | 12.19 (8.46) | 13.94 (8.51) | 1.10 | .271 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 11.82 (13.31) | 7.65 (8.25) | 13.91 (14.84) | −2.49 | .003 |

| Depression | 22.80 (6.92) | 20.79 (7.07) | 23.80 (6.65) | 2.37 | .019 |

Note: Suicidal Ideation measured by SIQ-JR; Depression measured by RADS-2-SF.

Correlations among Primary Study Variables

Suicidal ideation was positively correlated with perceived burdensomeness (p < .001), low interpersonal connectedness (p < .01), bully victimization (p < .01), and depression (p <.001). Suicidal ideation was also negatively correlated with family (p < .001) and school (p < .001) connectedness; however, it was not significantly correlated with peer connectedness. Similarly, perceived burdensomeness was negatively correlated with family (p < .001) and school connectedness (p < .01), but not with peer connectedness. Perceived burdensomeness was also found to be correlated with bully perpetration (p < .05), low interpersonal connectedness (p < .01), and depression (p < .001). Table 2 displays correlations among primary study variables.

Table 2.

Correlations of Connectedness and Maladjustment in At-Risk Adolescents

| Variable | Bully Victimization |

Bully Perpetration |

UCLA Loneliness |

Family Conn. |

School Conn. |

Peer Conn. |

Perceived Burdensomeness |

Suicidal Ideation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bully Perpetration | .23 (.008) | |||||||

| UCLA Loneliness | −.15 | −.11 | ||||||

| Family Conn. | .09 | <.01 | −.44 (<.001) | |||||

| School Conn. | −.06 | −.09 | −.27 (.002) | .43 (<.001) | ||||

| Peer Conn. | .17 | −.03 | −.33 (<.001) | .30 (.001) | .30 (.001) | |||

| Perceived Burdensomeness | .07 | .20 (.026) | .30 (.001) | −.47 (<.001) | −.24 (.008) | −.14 | ||

| Suicidal Ideation | .24 (.006) | .09 | .23 (.008) | −.41 (<.001) | −.40 (<.001) | −.08 | .56 (<.001) | |

| Depression | .05 | .06 | .43 (<.001) | −.62 (<.001) | −.48 (<.001) | −.17 | .50 (<.001) | .59 (<.001) |

Note: Numbers inside parenthesis display significance values <.05; Conn. = Connectedness; Suicidal Ideation measured by SIQ-JR; Depression measured by RADS-2-SF.

Hierarchical Regression

A hierarchical regression model was created (see Table 3) to examine associations with suicidal ideation. The following variables were used as covariates and were added in the first step: bully victimization, bully perpetration, sex, and depression. Bully victimization and bully perpetration were entered as control variables to account for their association with increases in suicidal ideation (e.g., Brunstein-Klomek et al., 2007). Sex was entered as a control variable to account for well-established sex differences in prevalence and severity of suicidal ideation (e.g., Roland, 2002). Additionally, because a number of sex differences was found in the sample (see Table 1), sex was considered to be an important covariate. Finally, depression was entered as a control variable to investigate whether the interactions between perceived burdensomeness and each social connectedness variable added incremental validity to the prediction of suicidal ideation, over and above the well-established association between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (e.g., Hawton, Casañas i Comabella, Haw, & Saunders, 2013).The three types of connectedness were entered in the second step to determine which connectedness variables were significantly associated with the outcome variable while accounting for other forms of connectedness. In step three, perceived burdensomeness was added to the model. In step four, to test the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior, interactions between the three social connectedness variables (i.e., family, school, and peer) and perceived burdensomeness were included separately. All variables included in the interaction term (i.e., social connectedness variables and perceived burdensomeness) were centered to limit the effect of multicollinearity. To address the normality assumption, suicidal ideation was transformed with the square root method. No differences were found in the pattern of significant findings, therefore untransformed results are reported for ease of interpretation. A detailed description of each step is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Suicidal Ideation in At-Risk Adolescents

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | F | R2 | ΔR2 | β | SE β | B | p |

| Step 1 | 20.67 | .404 | - | <.001 | |||

| Sex | −3.31 | 2.05 | −.117 | .109 | |||

| Bully Victimization | 0.45 | 0.15 | .209 | .004 | |||

| Bully Perpetration | 0.09 | 0.20 | .035 | .636 | |||

| Depressiona | 1.06 | 0.14 | .553 | <.001 | |||

| Step 2 | 12.19 | .418 | .014 | <.001 | |||

| Sex | −2.47 | 2.20 | −.088 | .264 | |||

| Bully Victimization | 0.45 | 0.16 | .210 | .005 | |||

| Bully Perpetration | 0.06 | 0.20 | .023 | .752 | |||

| Depression | 0.90 | 0.18 | .467 | <.001 | |||

| Family Connectedness | −0.08 | 0.14 | −.057 | .570 | |||

| School Connectedness | −0.29 | 0.20 | −.124 | .144 | |||

| Peer Connectedness | 0.04 | 0.17 | .019 | .801 | |||

| Step 3 | 15.28 | .509 | .091 | <.001 | |||

| Sex | −2.91 | 2.03 | −.103 | .155 | |||

| Bully Victimization | 0.41 | 0.15 | .191 | .006 | |||

| Bully Perpetration | −0.11 | 0.19 | −.040 | .561 | |||

| Depression | 0.66 | 0.18 | .342 | <.001 | |||

| Family Connectedness | 0.08 | 0.13 | .057 | .548 | |||

| School Connectedness | −0.36 | 0.18 | −.154 | .052 | |||

| Peer Connectedness | 0.06 | 0.16 | .027 | .701 | |||

| Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.58 | 0.12 | .370 | <.001 | |||

| Step 4 | 14.78 | .532 | .023 | <.001 | |||

| Sex | −2.30 | 2.01 | −.082 | .254 | |||

| Bully Victimization | 0.40 | 0.14 | .185 | .007 | |||

| Bully Perpetration | −0.12 | 0.18 | −.046 | .498 | |||

| Depression | 0.64 | 0.17 | .336 | <.001 | |||

| Family Connectedness | 0.04 | 0.13 | .026 | .780 | |||

| School Connectedness | −0.33 | 0.18 | −.141 | .069 | |||

| Peer Connectedness | 0.06 | 0.16 | .026 | .714 | |||

| Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.50 | 0.13 | .322 | <.001 | |||

| Family×Burdensomenessb | −0.03 | 0.01 | −.161 | .018 | |||

Note: Suicidal Ideation measured by SIQ-JR; Depression measured by RADS-2-SF.

Removing RADS-2-SF item “I feel lonely”, suggesting low connectedness, from analyses does not alter results. Reported results are based on all RADS-2 items.

Interactions between school and peer connectedness by perceived burdensomeness were not statistically significant.

Family connectedness and perceived burdensomeness

The final model predicting suicidal ideation (step four of Table 3) accounted for 53.2% of the variance in the dependent variable (F (9,117) = 14.78, p < .001). This model included the interaction between low family connectedness and perceived burdensomeness, which was the only significant interaction (B = −.161, p < .05). This interaction provides evidence that the slope of the regression line representing the association between family connectedness and suicidal ideation for those with higher perceived burdensomeness (n = 80) is significantly different from the slope for those with lower perceived burdensomeness (n = 49) scores. Additional post-hoc analyses are described below that investigate whether these simple regression slopes are significantly different from zero. Bully victimization (B = .185, p < .01) and depression (B = .336, p < .001) remained significant in this model. However, the model including the interaction between school connectedness and burdensomeness was not significant (B = −.066, p = .34), nor was the model including the interaction between peer connectedness and burdensomeness (B = .017, p = .80).

Post-Hoc Analyses

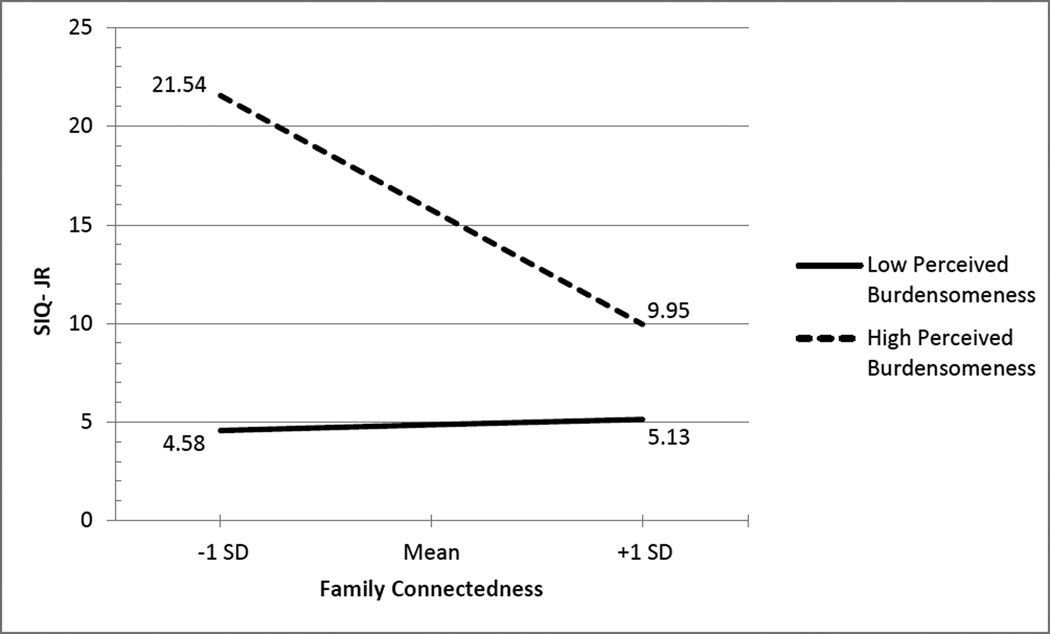

Post-hoc analyses, based on strategies recommended by Holmbeck (2002) were conducted to further investigate the significant interaction between family connectedness and perceived burdensomeness and the association of these variables with suicidal ideation, as measured by the SIQ-JR (see Figure 1). Perceived burdensomeness was adjusted, using the standard deviation value of 8.50, to create two conditional moderator variables: high perceived burdensomeness and low perceived burdensomeness. Two separate multiple regression models were then performed with these variables. These models included family connectedness, either high or low perceived burdensomeness, and their interaction. Substituting zero for the conditional moderator variables in each regression equation, we obtained two regression line equations: one representing high perceived burdensomeness (t(127) = -3.66, p < .001) and the other low perceived burdensomeness (t(127) = 0.19, p = .847). The standard deviation positive and negative values for family connectedness (9.56) were then substituted into each equation to produce four SIQ-JR mean scores, each representing one of the following groups: low family connectedness, low burdensomeness (M = 4.58); high family connectedness, low burdensomeness (M = 5.13); low family connectedness, high burdensomeness (M = 21.54); high family connectedness, high burdensomeness (M = 9.95). These data are graphed in Figure 1. The significant simple slope regression line for high perceived burdensomeness (reported above) provides evidence that suicidal ideation was greater at lower levels of family connectedness when perceived burdensomeness was high.

Figure 1.

Family Connectedness by Perceived Burdensomeness Interaction

Note. SIQ-JR = Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior.

Discussion

This study examined the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior within a sample of adolescents at elevated risk for suicidal behavior due to interpersonal problems (i.e., bully victimization, bully perpetration, and/or low interpersonal connectedness). In line with the theory, low family connectedness (thwarted belongingness) combined with a high sense of perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with more severe suicidal ideation in these adolescents. These results provide evidence that the simultaneous presence of low family connectedness and high burdensomeness predicted suicidal ideation above and beyond what the two components could predict individually. Explained another way, when perceived burdensomeness was high, lower levels of family connectedness were associated with more severe suicidal ideation. However, when perceived burdensomeness was low, the degree of family connectedness did not affect the severity of suicidal ideation. The results suggest that, even though interpersonal problems are a risk factor for suicidal ideation, it is those adolescents who have an unmet need of belonging within the context of their family and who feel like a burden on others that are particularly at elevated risk. Additionally, this study’s findings demonstrate strong psychometric properties of the burdensomeness scale of the INQ in the parent study’s overall adolescent sample (α = 0.89) and convergent validity in this study’s sample of at-risk adolescents.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior to understanding suicidal ideation among adolescents at elevated risk for suicidal behavior. Previous studies that directly tested this theory focused on adult psychiatric patients and college students (Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden et al., 2008). In addition, we further expanded on previous studies by considering different domains of connectedness in combination with perceived burdensomeness, given the developmental significance of peer relationships in adolescents and the fact that different types of connectedness seem to have distinct patterns of association with suicidal ideation (e.g., Czyz et al., 2012; Resnick et al., 1997). Surprisingly, when perceived burdensomeness was higher, only a sense of thwarted belongingness with family, but not peers or school, was associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation. This suggests that when at-risk adolescents experience themselves as not worthwhile or a burden on others—perhaps as a result of being bullied, bullying others, or not being connected to others—family relationships that are low on support and closeness can further exacerbate the negative effects of bully victimization. We hypothesize that school and peer connectedness did not interact significantly with perceived burdensomeness when estimating suicidal ideation because adolescents may not feel as much as a burden in these contexts. In fact, adolescents may actually feel that school is a burden on them. Adolescents may also not feel like a burden on their peers because of having greater choice about whom they associate with, a relational component not found for family. Furthermore, with regard to family, adolescents may feel like a burden because it is assumed that their families are supposed to take care of them, creating a context in which feeling like a burden might be more possible.

Connectedness Variables

In this sample of at-risk adolescents, family and school connectedness were both correlated with suicidal ideation; however, peer connectedness was not. These results are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Kaminski et al., 2010) and suggest that family and school connectedness matter when trying to decrease levels of suicidal ideation for peer bullied adolescents. Mental health programs should emphasize prevention and intervention approaches that facilitate gains in family and school connectedness among at-risk adolescents.

Sex Differences

An examination of sex differences yielded higher levels of reported family and school connectedness for males; however, there was no significant sex difference in peer connectedness. These results were somewhat surprising considering that past studies involving community samples have shown adolescent girls report greater levels of family, school, and peer connectedness (e.g.., Kaminski et al., 2010; Karcher & Sass, 2010). This discrepancy may be due to the unique characteristics found within our sample of at-risk adolescents or due to our sample’s high percentage of African American youth (55.0%; Witherspoon, Schotland, Way, &Hughes, 2009), both of which do not have well established sex differences for connectedness variables. Overall, males in this sample may be more likely to search and find support among family members and teachers. Finally, females reported higher levels of suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms than males, a finding that is consistently reported in the literature (e.g., Roland, 2002).

Limitations

The study sample was comprised of adolescents at-risk for suicide due to interpersonal problems who were identified in an urban medical emergency department in one region of the United States, are disproportionately female, and are taken from a larger effectiveness trial with an overall consent rate of 79.6%, each of which limit the study’s generalizability. Similarly, because a history of suicide attempt was an exclusion criterion in this study, the severity of suicide risk in our sample may be limited and findings cannot be generalized to adolescents who have already engaged in suicidal behavior. It should be noted, however, that previous suicidal behavior was relatively uncommon in this sample of youth ages 12–15 years, and this study can thus inform how to prevent the onset of suicidal behavior. Additional study limitations include the relatively small sample size of 129 participants and the possibility that results are influenced by shared method variance, as all study measures were based on adolescent self-report. Finally, this study is cross-sectional, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn and the possibility of addressing the theory’s predictive validity.

Implications and Future Directions

Our study suggests that particular attention is warranted toward at-risk adolescents who, in addition to experiencing themselves as a burden on others, are experiencing a low sense of belonging within their families. Helping these adolescents question their beliefs of not being worthwhile or a burden on others – a perception that is likely to be internalized in the context of interpersonal problems – in addition to fostering greater connections with their families could protect these teens from experiencing thoughts of suicide, and from suicidal behavior.

In this sample of at-risk adolescents, while family connectedness played an important role in determining whether or not an adolescent reported suicidal ideation, perceived burdensomeness was the factor that created a significant change in suicidal ideation (as seen in Table 1). Longitudinal studies are recommended that investigate the relationship between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in both adolescents who are at-risk for suicide and those who are not. Should empirical evidence continue to support these components of the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior, primary and tertiary interventions should begin to investigate the efficacy of strategies targeting these components.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adam Horwitz for database development; Deborah Stone for input on an earlier version of this manuscript; Tasha Kelley-Stiles, M.S.W., and Bianca Burch, L.M.S.W., for recruitment and project implementation; Hanadi Abdallah, Kevin Kuehn, Elissa Sarno, Surya Sambandan, Yun Chen, Mohamad Idriss, William Benjamin Rogers, and Jessica Foksa for research assistance. We also thank the families who took part in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by a CDC grant (U01-CE-001940-01) and NIMH K24 (MH077705) award to Dr. Cheryl King.

References

- Brunstein-Klomek A, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(1):40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [Retrieved May 8, 2013];2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- Czyz EK, Liu Z, King CA. Social connectedness and one-year trajectories among suicidal adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(2):214–226. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gecková A, Van Dijk JP, Stewart R, Groothoff JW, Post D. Influence of social support on health among gender and socio-economic groups of adolescents. European Journal of Public Health. 2003;13(1):44–50. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Casañas i Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pettit JW, Walker RL, Voelz ZR, Cruz J, Rudd MD, Lester D. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: Two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2002;21(5):531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, Rudd MD. Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Puddy RW, Hall DM, Cashman SY, Crosby AE, Ortega LAG. The relative influence of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed violence in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(5):460–473. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ. The Hemingway: Meausre of Adolescent Connectedness: A manual for scoring and interpretation. University of Texas at San Antonio; 2011. [Retrieved March 25th, 2014]. Unpublished manuscript from http://adolescentconnectedness.com/media/HemingwayManual2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ, Sass D. A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: Testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(3):274–289. doi: 10.1037/a0019357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Preuss LJ, King CA. Suicidal Adolescents' Social Support from Family and Peers: Gender-Specific Associations with Psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(1):103–114. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Merchant CR. Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: A review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12(3):181–196. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JE, Crosby AE, Hamburger ME. Suicidal ideation, friendships with delinquents, social and parental connectedness, and differential associations by sex: Findings among high-risk pre/early adolescent population. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2011;32(6):299–309. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski A. The dimensionality of the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 1990;13:45–52. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski TJ, Yarcheski A. Validation of the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale for adolescents. Research in Nursing and Health. 1995;18:263–270. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milfont TL, Merry S, Robinson E, Denny S, Crengle S, Ameratunga S. Evaluating the short form of the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale in New Zealand adolescents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42(11):950–954. doi: 10.1080/00048670802415343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretty GMH, Andrews L, Collet C. Exploring adolescent's sense of community and its relationship to loneliness. Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(4):479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Measurement of suicidal ideation in adolescents; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Suicidology; Chicago, IL. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Roland E. Bullying, depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts. Educational Research. 2002;44(1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Curtrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1978;42:290–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(8):1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbath JC. The suicidal adolescent: The expendable child. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1969;8(2):272–285. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE., Jr Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(1):197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Lynam ME, Hollar D, Joiner TE., Jr Perceived Burdensomeness as an Indicator of Suicidal Symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(4):457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE., Jr Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Jacobs AK, Hershberger SL. Peer victimization and attitudes about violence during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(3):386–395. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, Botticello AL, Aneshensel CS. Socioeconomic Context, Social Support, and Adolescent Mental Health: A Multilevel Investigation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(1):115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon D, Schotland M, Way N, Hughes D. Connecting the dots: How connectedness to multiple contexts influences the psychological and academic adjustment of urban youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2009;13(4):199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Woznica JG, Shapiro JR. An analysis of adolescent suicide attempts: The expendable child. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990;15(6):789–796. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]