Abstract

The local renin-angiotensin system promotes angiogenesis and vascular proliferation via expression of vascular endothelial growth factor or epidermal growth factor receptor. We hypothesized that angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) in combination with bevacizumab (Bev) may improve clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). A total of 181 patients with histopathologically confirmed mCRC treated with first-line oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in combination with Bev were enrolled between June, 2007 and September, 2010. The patients were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of treatment with ARBs prior to the initiation of second-line chemotherapy. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazard modeling were used in the statistical analysis. The median progression-free survival (PFS) in patients undergoing second-line chemotherapy in combination with Bev and ARBs (n=56) vs. those treated in the absence of ARBs (n=33) was 8.3 vs. 5.7 months, respectively [hazard ratio (HR)=0.57, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.35–0.94, P=0.028]. The median overall survival (OS) was 26.5 vs. 15.2 months, respectively (HR=0.47, 95% CI: 0.25–0.88, P=0.019). In the multivariate analysis, the use of ARBs was independently associated with prolongation of OS and PFS. In conclusion, the use of ARBs prolonged survival in mCRC patients.

Keywords: angiogenesis, angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers, bevacizumab, vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

The systemic renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is associated with cardiovascular regulation. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) are among the most widely used antihypertensive drugs. The local RAS reportedly promotes angiogenesis and vascular proliferation via expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or epidermal growth factor receptors (1,2). The use of ACEIs was associated with a decreased cancer incidence in a large cohort study, and the potential role of the local RAS in carcinogenesis has attracted significant attention (3). For example, the growth of gastric cancer cells was significantly suppressed by treatment with angiotensin II type-1 receptor (AT1R) antagonists (4). Moreover, AT1R antagonists have been found to prevent angiogenesis and growth of xenograft tumors developed by human bladder cancer cells (5). AT1R antagonists induced downregulation of AT1R expression in the endothelial cells of microvessels in pancreatic cancer. Such downregulation of AT1R may weaken the angiogenetic and tumor-proliferative effects of angiotensin (6). Synergistic inhibition of tumor growth through suppression of VEGF by combined gemcitabine (GEM) and losartan treatment has been demonstrated in murine pancreatic cancer (7). A retrospective analysis by Nakai et al suggested that ACEIs or ARBs in combination with GEM may improve clinical outcomes, in terms of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (8).

The systemic administration of oxaliplatin with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine (XELOX) and bevacizumab (Bev) is the standard first-line chemotherapeutic regimen in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). We hypothesized that ARBs in combination with Bev-based chemotherapy may improve clinical outcomes in mCRC patients. The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyze clinical outcomes in mCRC patients receiving Bev, in order to elucidate the effect of ARBs.

Patients and methods

Patients

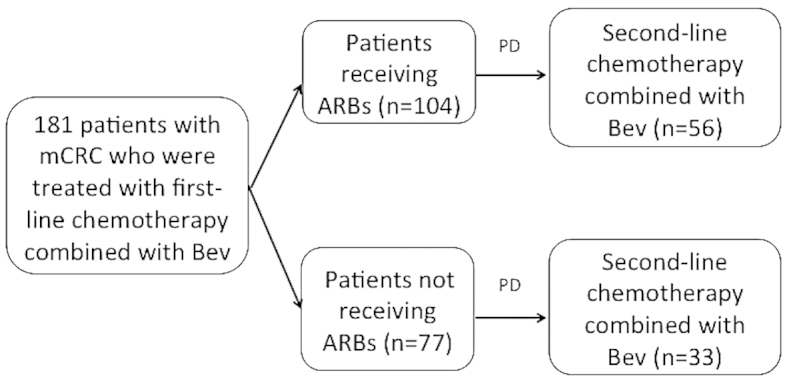

All mCRC patients receiving first-line Bev-based chemotherapy at the Department of Gastroenterology, The Cancer Institute Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) between June, 2007 and September, 2010 were retrospectively investigated. The use of medications to control hypertension (HT), including ARBs, was retrospectively determined from the medical records and the patients were divided into two groups: An ARB group (patients receiving ARBs as HT medication), and a non-ARB group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A total of 181 patients with histopathologically confirmed metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) treated with first-line oxaliplatin-based standard chemotherapy in combination with bevacizumab (Bev) were enrolled between June, 2007 and September, 2010. The patients were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of treatment with angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) prior to the initiation of second-line chemotherapy. PD, progressive disease.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Institute Hospital (registry no. 1244).

Treatment and tumor response

The FOLFOX regimen was administered as follows: Oxaliplatin on day 1 at a dose of 85 mg/m2 as a 2-h infusion concurrent with folinic acid 400 mg/m2/day, followed by bolus 5-FU 400 mg/m2 and a 22-h infusion of 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 for 2 consecutive days. Bev was administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg in a 30-min intravenous infusion on day 1 in 2-week cycles. The XELOX regimen was administered as follows: Capecitabine 2,000 mg/m2 biweekly, plus oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day 1. Bev was administered at a dose of 7.5 mg/kg in a 30-min intravenous infusion on day 1 in 3-week cycles. These regimens were repeated every 2 or 3 weeks, until disease progression or development of unacceptable toxicity, or until the patient requested treatment discontinuation. Tumor response was assessed via computed tomography using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1 (9). The evaluation was repeated every 3 (or 4) courses, or more frequently in patients with clinically suspected disease progression.

Statistical analysis

OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All the reported P-values were the result of two-sided tests, with P<0.05 considered to indicate statistically significant differences. To exclude possible confounding factors, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for the use of ARBs adjusted for significant prognostic factors. The prognostic factors included age (<65 or ≥65 years), gender (male or female), performance status (0–1 or 2), site of metastasis (liver, lung, lymph nodes, or peritoneum), multiple metastases (yes or no), ascites (yes or no), treatment group (ARB or non-ARB) and HT (grade 0 or 1/2/3). The prognostic factors with P<0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 181 patients who received first-line Bev-based chemotherapy, 104 received ARBs. The median follow-up period was 2.2 years (26.7 months). No significant differences were observed in the baseline clinical characteristics between the two groups (Table I).

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| A, Intention-to-treat population (n=181) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ARB (n=104) | Non-ARB (n=77) | |

| Gender, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 56 (53.9) | 44 (57.1) | |

| Female | 48 (46.1) | 33 (42.9) | |

| Age, years [median (range)] | 61.5 (38–75) | 55 (16–74) | |

| <65, no. (%) | 61 (58.7) | 61 (79.2) | |

| ≥65, no. (%) | 43 (41.3) | 16 (20.8) | |

| ECOG PS at baseline, no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 100 (96.2) | 74 (96.1) | |

| 1 | 4 (3.8) | 3 (3.9) | |

| Metastatic location, no. (%) | |||

| Liver | 47 (45.1) | 45 (58.4) | |

| Lung | 43 (41.3) | 32 (41.5) | |

| Lymph nodes | 47 (45.1) | 44 (57.1) | |

| Multiple | 59 (56.7) | 55 (71.4) | |

| B, ARB group | |||

| Characteristics | KRAS WT (n=63) | KRAS MT (n=30) | Unknown (n=11) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 35 (55.6) | 14 (46.7) | 7 (63.6) |

| Female | 28 (44.4) | 16 (53.3) | 4 (36.4) |

| Age, years [median (range)] | 60.31 (38–74) | 64 (48–75) | 61.45 (46–73) |

| <65, no. (%) | 39 (61.9) | 15 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| ≥65, no. (%) | 24 (38.1) | 15 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| Metastatic location, no. (%) | |||

| Liver | 30 (47.6) | 12 (40.0) | 5 (45.4) |

| Lung | 23 (36.5) | 16 (53.3) | 4 (36.3) |

| Lymph nodes | 31 (49.2) | 12 (40.0) | 4 (36.3) |

| Multiple | 35 (55.5) | 19 (63.3) | 5 (45.4) |

| C, Non-ARB group | |||

| Characteristics | KRAS WT (n=47) | KRAS MT (n=16) | Unknown (n=14) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 23 (48.9) | 12 (75.0) | 7 (50.0) |

| Female | 24 (51.1) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (50.0) |

| Age, years [median (range)] | 55.9 (27–73) | 55.6 (39–74) | 65.8 (16–71) |

| <65, no. (%) | 39 (82.9) | 12 (75.0) | 12 (85.7) |

| ≥65, no. (%) | 8 (17.1) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (14.3) |

| Metastatic location, no. (%) | |||

| Liver | 33 (70.2) | 7 (43.0) | 5 (35.7) |

| Lung | 21 (44.6) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (50.0) |

| Lymph nodes | 24 (51.0) | 4 (25.0) | 11 (78.5) |

| Multiple | 33 (70.2) | 9 (56.2) | 13 (92.8) |

ARB, angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; WT, wild-type; KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; MT, mutant type.

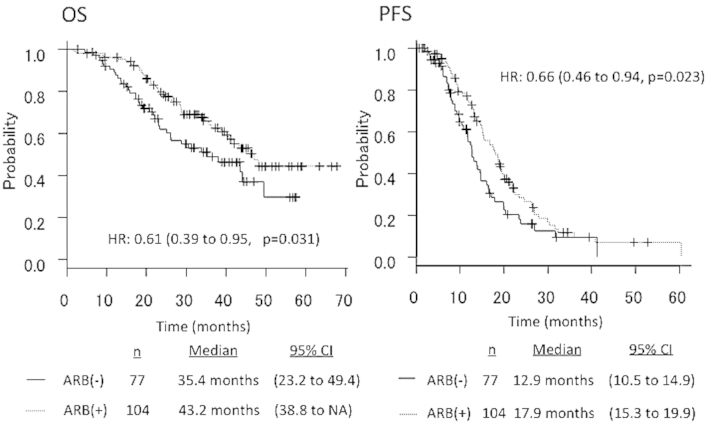

Patient survival

The median PFS in patients receiving ARBs (n=104) vs. those not receiving ARBs (n=77) was 17.9 vs. 12.9 months, respectively (HR=0.66, 95% CI: 0.46–0.94, P=0.023). The median OS in patients receiving ARBs (n=104) vs. those not receiving ARBs (n=77) was 43.2 vs. 35.4 months, respectively (HR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.39–0.95, P=0.031) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) curves according to the presence or absence of treatment with angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) in the total patient population (n=181). HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available.

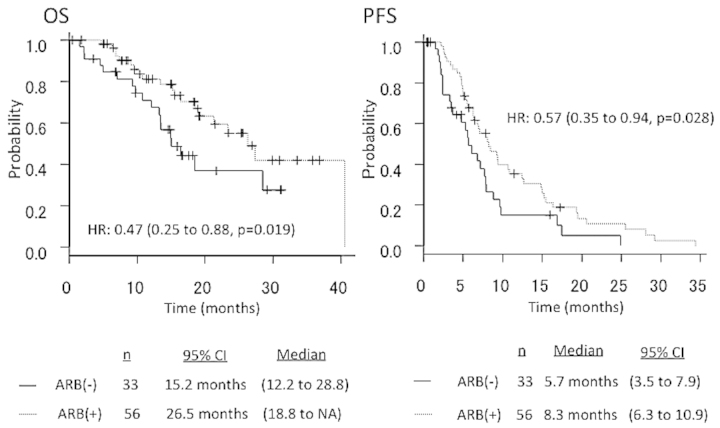

The median PFS in patients who underwent second-line Bev-based chemotherapy with ARBs (n=56) vs. those without ARBs (n=33) was 8.3 vs. 5.7 months, respectively (HR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.35–0.94, P=0.028). The median OS in patients who underwent second-line Bev-based chemotherapy with ARBs (n=56) vs. those without ARBs (n=33) was 26.5 vs. 15.2 months, respectively (HR=0.47, 95% CI: 0.25–0.88, P=0.019) (Fig. 3). The overall response rates according to RECIST were 68.5% (124/181) in total, 74.0% (77/104) in patients receiving ARBs, and 61.0% (47/77) in patients not receiving ARBs (Table II). In the multivariate analysis, the use of ARBs was independently associated with prolongation of OS and PFS (first- and second-line) (Table III).

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) curves according to the presence or absence of treatment with angiotensin II type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients receiving second-line chemotherapy. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available.

Table II.

Response to treatment in patients undergoing first- and second-line chemotherapy in combination with Bev and ARBs.

| A, Overall response rate in patients undergoing first-line chemotherapy in combination with Bev and ARBs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response, no. (%) | ARB (n=104) | Non-ARB (n=77) | |

| Complete response | 8 (7.7) | 4 (5.2) | |

| Partial response | 69 (66.3) | 44 (57.1) | |

| Stable disease | 24 (23.1) | 19 (24.7) | |

| Progressive disease | 2 (1.9) | 5 (6.5) | |

| Not evaluable | 1 (1.0) | 5 (6.5) | |

| Best overall response rate | |||

| All patients, no. (%) | 77 (74.0) | 48 (61.0) | |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.81 (0.91–3.60) | ||

| P-value | 0.075 | ||

| B, Disease control rate in patients undergoing second-line chemotherapy in combination with Bev and ARBs | |||

| Best overall response, no. (%) | ARB (n=56) | Non-ARB (n=33) | |

| Complete response | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Partial response | 2 (3.6) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Stable disease | 44 (78.6) | 19 (57.6) | |

| Progressive disease | 8 (14.2) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Not evaluable | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Disease control rate | |||

| All patients, no. (%) | 47 (83.9) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.34 (1.11–10.4) | ||

| P-value | 0.021 | ||

Bev, bevacizumab; ARB, angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval.

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line | |||

| Univariate analysis | |||

| OS | |||

| Gender | 0.88 | 0.55–1.4 | 0.6 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95–1 | 0.1 |

| Ascites | 1.7 | 0.9–3.5 | 0.09 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 2.1 | 1.3–3.5 | 0.001 |

| Lung | 0.95 | 1–1.5 | 0.84 |

| Lymph nodes | 2 | 1.2–3.2 | 0.004 |

| Peritoneum | 1.37 | 0.8–2.1 | 0.18 |

| Multiple | 2.2 | 1.3–3.8 | 0.001 |

| Performance status | 2.7 | 0.8–8.9 | 0.08 |

| ARB | 0.6 | 0.37–0.96 | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 0.79 | 0.38–1.6 | 0.52 |

| PFS | |||

| Gender | 0.55 | 0.25–1.2 | 0.12 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.63 |

| Ascites | 1.2 | 0.7–2 | 0.4 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 1.9 | 1.3–2.8 | 0.0002 |

| Lung | 2 | 1.4–2.9 | 0.00007 |

| Lymph nodes | 1.04 | 0.73–1.49 | 0.8 |

| Peritoneum | 1.8 | 1.2–2.6 | 0.002 |

| Multiple | 1.2 | 0.4–3.5 | 0.72 |

| Performance status | 1.05 | 0.38–2.88 | 0.91 |

| ARB | 0.66 | 0.46–0.94 | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 0.81 | 0.47–1.4 | 0.46 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| OS | |||

| ARB | 0.64 | 0.40–1.0 | 0.056 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 1.92 | 1.21–3.0 | 0.005 |

| Lymph nodes | 2.1 | 1.3–3.3 | 0.0016 |

| PFS | |||

| ARB | 0.68 | 0.47–0.98 | 0.043 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Lung | 2.2 | 1.5–3.0 | 0.00005 |

| Liver | 2.08 | 1.45–2.99 | 0.00006 |

| Second-line | |||

| Univariate analysis | |||

| OS | |||

| Gender | 0.92 | 0.48–1.7 | 0.8 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95–1 | 0.43 |

| Ascites | 1.3 | 0.4–3.7 | 0.6 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 3.3 | 1.6–7 | 0.001 |

| Lung | 0.54 | 0.27–1 | 0.08 |

| Lymph nodes | 2 | 1.2–3.2 | 0.004 |

| Peritoneum | 1.5 | 0.8–2.9 | 0.18 |

| Multiple | 3 | 1.3–6.8 | 0.007 |

| Performance status | 0.9 | 0.85–1.1 | 0.99 |

| ARB | 0.47 | 0.25–0.88 | 0.019 |

| Hypertension | 0.41 | 0.18–0.94 | 0.03 |

| PFS | |||

| Gender | 0.93 | 0.57–1.5 | 0.77 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.31 |

| Ascites | 1.2 | 0.7–2 | 0.4 |

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 1.8 | 1.1–3 | 0.01 |

| Lung | 0.93 | 0.58–1.4 | 0.7 |

| Lymph nodes | 1.7 | 1–2.7 | 0.03 |

| Peritoneum | 1 | 0.66–1.7 | 0.73 |

| Multiple | 1.8 | 1–3 | 0.025 |

| Performance status | 1 | 0.14–7.5 | 0.96 |

| ARB | 0.57 | 0.35–0.9 | 0.028 |

| Hypertension | 0.85 | 0.39–1.8 | 0.7 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| OS | |||

| Metastatic location | |||

| Liver | 2.7 | 1.32–5.8 | 0.007 |

| Lymph nodes | 2.8 | 1.3–5.9 | 0.006 |

| Peritoneum | 2.7 | 1.38–5.5 | 0.003 |

| ARB | 0.45 | 0.24–0.86 | 0.01 |

| PFS | |||

| ARB | 0.49 | 0.3–0.82 | 0.006 |

| Liver metastasis | 2.1 | 1.3–3.5 | 0.002 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; ARB, angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker.

Discussion

The use of ARBs has been associated with longer OS and PFS in patients with mCRC who undergo first-line Bev-based chemotherapy. This suggests that the suppression of RAS may inhibit tumor growth and improve survival. Lever et al(3) reported that the use of ACEIs was associated with a decreased cancer incidence in a large cohort study and the potential role of the local RAS in carcinogenesis has attracted significant attention. The involvement of the local RAS in pancreatic cancer was suggested due to the expression of AT2 and the AT1R in human pancreatic cancer (10,11). It has been demonstrated that ACEIs and ARBs inhibit pancreatic cancer cell proliferation in vitro and delays murine pancreatic cancer progression in vivo via downregulation of VEGF expression (12,13). However, the growth of gastric cancer cells was significantly suppressed by treatment with AT1R antagonists. AT1R antagonists were shown to prevent angiogenesis and the growth of xenograft tumors developed by human bladder cancer cells (5). The crucial role of angiogenesis in tumor growth has been widely recognized, and several reports have revealed that combination treatment with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs and anti-angiogenic agents exert synergistic anticancer effects (14). It has been reported that ARBs clinically exert potent anti-angiogenic activity (7).

GEM exhibits a marked anticancer effect, as a result of its cytotoxic action, and an anti-angiogenic effect. It has been reported that GEM inhibited neovascularization in a human pancreatic tumor in nude mice in a very low-dose metronomic schedule. The synergistic inhibition of tumor growth through suppression of VEGF by combined GEM and losartan treatment has been demonstrated in murine pancreatic cancer. In addition, the inhibition of RAS was also reported to induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells (15,16). A retrospective analysis by Nakai et al suggested that ACEIs or ARBs in combination with GEM improve clinical outcome in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (8).

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical outcome of mCRC patients who underwent standard chemotherapy with Bev to elucidate the effect of ARBs. The results demonstrated that the presence of ARBs prior to the initiation of second-line chemotherapy prolonged OS and PFS (first- and second-line). The induction rate of second-line chemotherapy was similar between the two groups (Table IV). The development of Bev-induced arterial HT has recently been suggested as a potential predictive marker. Certain studies have reported that HT may predict Bev treatment efficacy, regardless of the analyzed endpoint (OS, PFS, or response rate) (17–21). In the present study, second-line OS tended to be longer in patients developing HT. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the multivariate analysis.

Table IV.

Second-line anticancer treatment.

| Agents | ARB, no. (%) | Non-ARB, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cetuximab | 44 (42.3) | 33 (42.8) |

| Panitummab | 5 (4.8) | 5 (6.4) |

| Bevacizumab | 58 (55.7) | 38 (49.3) |

| Irinotecan | 67 (64.4) | 51 (66.2) |

| Oxaliplatin | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Capecitabine | 5 (4.8) | 5 (6.4) |

| 5-FU/FA | 60 (57.6) | 44 (57.1) |

| Other | 5 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) |

ARB, angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker; 5-FU/FA, 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that OS and PFS were longer in mCRC patients who underwent Bev-based chemotherapy with ARBs, compared with those who did not receive ARBs. However, further prospective clinical trials are required to verify this hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

S. Matsusaka received a commercial research grant from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; E. Shinozaki received honoraria from the Speakers Bureau from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; N. Mizunuma received commercial research grants from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Merck Serono Co., Ltd., ONO Pharmaceutical CO., Ltd. and Bayer Yakuhin CO., Ltd.

References

- 1.Ager EI, Neo J, Christophi C. The renin-angiotensin system and malignancy. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1675–1684. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khakoo AY, Sidman RL, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Does the renin-angiotensin system participate in regulation of human vasculogenesis and angiogenesis? Cancer Res. 2008;68:9112–9115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lever AF, Hole DJ, Gillis CR, McCallum IR, McInnes GT, MacKinnon PL, Meredith PA, Murray LS, Reid JL, Robertson JW. Do inhibitors of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme protect against risk of cancer? Lancet. 1998;352:179–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang W, Wu YL, Zhong J, Jiang FX, Tian XL, Yu LF. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist suppress angiogenesis and growth of gastric cancer xenografts. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1206–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosugi M, Miyajima A, Kikuchi E, Kosaka T, Horiguchi Y, Murai M, Oya M. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist enhances cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum-induced cytotoxicity in mouse xenograft model of bladder cancer. Urology. 2009;73:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita M, Hayashi I, Yamashina S, Itoman M, Majima M. Blockade of angiotensin AT1a receptor signaling reduces tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:441–447. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noguchi R, Yoshiji H, Ikenaka Y, Namisaki T, Kitade M, Kaji K, Yoshii J, Yanase K, Yamazaki M, Tsujimoto T, et al. Synergistic inhibitory effect of gemcitabine and angiotensin type-1 receptor blocker, losartan, on murine pancreatic tumor growth via anti-angiogenic activities. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Ijichi H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Kogure H, Kawakubo K, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, et al. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system affects prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1644–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohta T, Amaya K, Yi S, Kitagawa H, Kayahara M, Ninomiya I, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, Shimizu K, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme-independent, local angiotensin II-generation in human pancreatic ductal cancer tissues. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto Y, Sasaki T, Tsuchida A, Chayama K. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in human pancreatic cancer and growth inhibition by angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:197–200. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arafat HA, Gong Q, Chipitsyna G, Rizvi A, Saa CT, Yeo CJ. Antihypertensives as novel antineoplastics: angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:996–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fendrich V, Chen NM, Neef M, Waldmann J, Buchholz M, Feldmann G, Slater EP, Maitra A, Bartsch DK. The angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril and aspirin delay progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer formation in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2010;59:630–637. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.188961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanase K, Yoshiji H, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Kitade M, Kaji K, Yoshii J, Namisaki T, Yamazaki M, Asada K, et al. Synergistic inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma growth and hepatocarcinogenesis by combination of 5-fluorouracil and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor via anti-angiogenic activities. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amaya K, Ohta T, Kitagawa H, Kayahara M, Takamura H, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, Shimizu K, Miwa K. Angiotensin II activates MAP kinase and NF-κB through angiotensin II type I receptor in human pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:849–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong Q, Davis M, Chipitsyna G, Yeo CJ, Arafat HA. Blocking angiotensin II type 1 receptor triggers apoptotic cell death in human pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 2010;39:581–594. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c314cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Österlund P, Soveri LM, Isoniemi H, Poussa T, Alanko T, Bono P. Hypertension and overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:599–604. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tahover E, Uziely B, Salah A, Temper M, Peretz T, Hubert A. Hypertension as a predictive biomarker in bevacizumab treatment for colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30:327. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewdney A, Cunningham D, Barbachano Y, Chau I. Correlation of bevacizumab-induced hypertension and outcome in the BOXER study, a phase II study of capecitabine, oxaliplatin (CAPOX) plus bevacizumab as peri-operative treatment in 45 patients with poor-risk colorectal liver-only metastases unsuitable for upfront resection. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1718–1721. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Ryanne R, Lindenberg PA, Slack R, Noone AM, Marshall JL, He AR. Evaluation of hypertension as a marker of bevacizumab efficacy. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009;40:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Chiorrini S, Giampieri R, Berardi R, Pierantoni C, Cascinu S. Arterial hypertension correlates with clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line bevacizumab. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:227–230. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]