Abstract

The intracellular parasite Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis) causes tuberculosis in cattle and humans. Understanding the interactions between M. bovis and host cells is essential in developing tools for the prevention, detection, and treatment of M. bovis infection. Gene expression profiles provide a large amount of information regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions. The present study analyzed changes in gene expression in bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at 0, 4 and 24 h following exposure to M. bovis. Using bovine whole-genome microarrays, a total of 420 genes were identified that exhibited significant alterations in expression (≥2-fold). Significantly enriched genes were identified using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database, of which the highest differentially expressed genes were associated with the immune system, signal transduction, endocytosis, cellular transport, inflammation, and apoptosis. Of the genes associated with the immune system, 84.85% displayed downregulation. These findings support the view that M. bovis inhibits signaling pathways of antimycobacterial host defense in bovine PBMCs. These in vitro data demonstrated that molecular alterations underlying the pathogenesis of tuberculosis begin early, during the initial 24 h following M. bovis infection.

Keywords: Mycobacterium bovis, global gene expression, immune response, macrophage

Introduction

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is caused by the intracellular pathogen Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), which is a facultative intracellular parasite of macrophages. BTB has a significant economic impact and serious implications for human health, particularly in developing countries (1). M. bovis can be transmitted to humans by infectious bacilli via respiratory contact with infected cattle, or consumption of unpasteurized dairy products (2). The host immune response to M. bovis infection is complex: Following initial exposure, T-helper cell-1 (Th1) innate immunity is induced. The bacilli are phagocytosed by host macrophages via pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (3,4). Signals transduced through these receptors result in the release of endogenous cytokines, which initiate the T-cell secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). The action of IFN-γ on infected macrophages promotes granuloma formation, which prevents the spread of infection (5). However, the pathogen often persists within granulomas, and this latent infection can recur as active tuberculosis. The mechanisms underlying evasion of the host immune response by M. bovis are not entirely understood; however they are known to involve the prevention of host phagosome maturation, the inhibition of apoptosis in infected macrophages, and the suppression of cell signaling pathways and cytokine production (6–8).

Genomic technologies can be used to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying immune responses to pathogens. With the availability of the complete Bos taurus genome (9), numerous studies have used bovine genome microarrays to analyze transcriptional changes induced by infection of various types of bovine cells with M. bovis (10,11). Killick et al (12) reported that M. bovis infection of peripheral blood leukocytes was associated with decreased expression levels of numerous host genes. Using an Affymetrix bovine genome array to investigate the effects of M. bovis challenge on bovine monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro, Magee et al (6) observed significant alterations in expression of genes associated with the inflammatory response, and cell signaling pathways, including TLRs, PRRs and apoptosis. Furthermore, the suppression of immune-associated genes has been detected in vivo in M. bovis-infected cattle (10).

These observations strongly suggest that M. bovis evades immune surveillance by altering the expression of genes essential to host immunity. The timing and potency of the cellular and immunological events that occur immediately after infection are suggested to be crucial determinants governing the outcome of an infection (13). Therefore, further elucidation of these early events in numerous types of host cells is essential for the prevention, detection, and treatment of M. bovis infections. The aim of the present study was to evaluate early changes in global gene expression in bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in response to M. bovis exposure. Microarray analyses were used to compare PBMC gene expression over a time course of 0, 4, and 24 h following exposure to M. bovis. Systems analysis was then used to determine the pathways and networks associated with the affected genes.

Materials and methods

PBMC preparation

The three 3-year-old female Holstein cattle with no recent history of BTB, which were used in the present study, were obtained from the National Taiwan University Experimental Farm (Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C). The cattle were maintained under uniform housing conditions (temperature, 25–28°C; humidity, 50–70%) and nutritional regimens; the cattle were fed twice a day with alfalfa and pangola grass hay and fresh, farm-grown grass, and all tested negative on tuberculin skin tests. All procedures described in the present study were reviewed and approved by the National Taiwan University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C). From each animal, 50 ml blood from the vein was collected in a sterile heparinized bottle and layered onto ACCUSPIN™ tubes containing Histopaque® 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following density gradient centrifugation (300 × g for 20 min at room temperature), the PBMCs were collected and cultured as previously described by Magee et al (6), with numerous modifications, including the use of an antibiotic-free culture media supplemented with NaHCO3 and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell cultures in 60 mm dishes (~5×106 cells/dish), were grown in RPMI (Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) and NaHCO3 to a final concentration of 26 mM at 37°C for 24 h in a culture incubator containing 5% CO2. The medium was then replaced with 1 ml fresh medium in order to remove any non-adherent cells. To ensure that the same number of PBMCs were subjected to M. bovis-challenge, 80–100% confluent monolayers of PBMCs were generated and counted on day 3, yielding ~5×106 cells per dishes, providing enough total RNA for microarray analysis. The cells were counted in Marienfeld® Thoma counting chamber (Celeromics Technologies, Grenoble, France), and trypan blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Luis, MO, USA) was used for the exclusion of dead cells.

Bacterial preparations

M. bovis strain 331-A1 (Animal Health Research Institute, New Taipei City, Taiwan, R.O.C), which was isolated in 2008 from cattle with tuberculosis, was used. The strain was confirmed by acid-fast staining using the Ziehl-Neelsen method, the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis of tuberculosis, and identified in mycobacterium culture by PCR and spoligotyping (14). The strain used was spoligotype SB0265, which is frequently isolated from cattle in Taiwan. The strain was cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 10% (v/v) Middlebrook albumin-dextrose-catalase (BD Biosciences), 0.05% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.40% (w/v) sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C. Bacterial suspensions were then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min at 25°C, and the pellets were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0), and resuspended in PBS prior to the determination of bacterial concentrations. A NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) was used to determine the optical density of the bacterial culture and calculate bacterial concentration in colony-forming u/ml. The concentration of the bacterial inoculum was 107 colony-forming units/ml. Fresh stocks of bacteria were prepared for each experiment.

In vitro challenge of PBMCs with M. bovis

When the PBMCs reached 80% confluence, three dishes for each M. bovis infection trial were randomly selected from the 20 dishes grown from cells collected from each cow. All in vitro challenge experiments included a non-challenge PBMC control for each time point. The cells were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ~2:1 (6), and control cultures were treated in the same manner using PBS instead of bacterial suspensions. Inoculated and control cultures were incubated for either 4 h (4-hours post-infection (hpi) group) or 24 h (24-hpi group). Total RNA was then extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration and purity of RNA extracts were verified optically using a spectrophotometer (ND-1000; Nanodrop Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), respectively.

Microarray analysis

Bovine V2 Oligo 4×44 K microarrays (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) were used to determine the differential gene expression between infected and control cells. For reverse transcription, second-strand cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 µg total RNA using the Fluorescent Linear Amplification kit containing T7 RNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The cDNA served as template for in vitro transcription to produce target cRNA labeled with Cy3-CTP (to label infected cells) and Cy5-CTP (to label control cells) (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Labeled cRNA (0.825 µg) was fragmented (mean size, ~50–100 nucleotides) in fragmentation buffer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at 60°C for 30 min. The prepared cRNA was subsequently hybridized to the microarray at 60°C for 17 h. Two replicates of the microarray assays (M1 and M2) were performed. Hybridized microarray chips were scanned using the Agilent Microarray Scanner with Feature Extraction software 9.5.3 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The locally weighted linear regression method was applied to normalize the results by rank consistency filtering.

Statistical analysis of microarray data

Microarray data were analyzed using GeneSpring GX 7.3.1 software (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). With a false discovery rate <0.05, data acquisition was conducted using the following criteria: i) P<0.01 for gene expression difference (GeneSpring); ii) a distinct signal from the microarray image that was flagged by the software; and iii) |-log 2-fold change| ≥2.5. Significantly enriched genes were identified using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), and the pathways and networks involving these genes were identified using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; http://norris.usc.libguides.com/IPA), a web-based functional analysis tool. The criteria for gene selection for IPA analysis were as follows: i) A fold-change in expression >2 for comparison between 0 and 4 hpi and >4 for comparison between 0 and 24 hpi, and ii) P<0.05 for changes in gene expression in cells from all three cows.

Results

Kinetics of gene expression during M. bovis infection

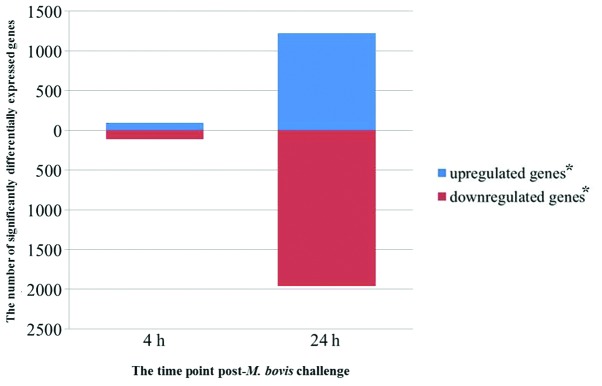

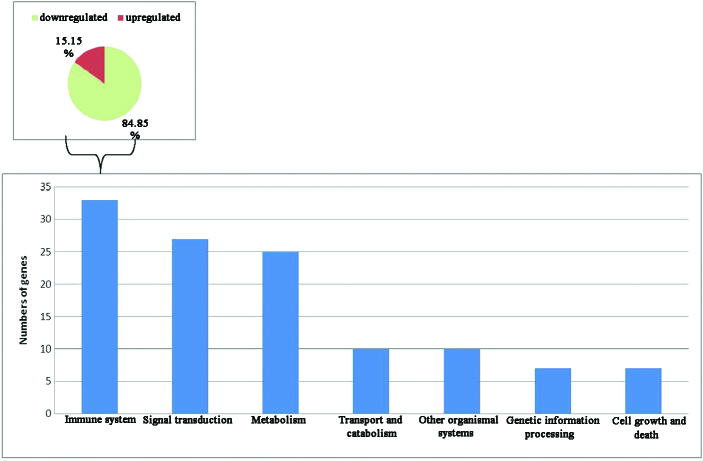

Comprehensive gene expression profiles of the three PBMC samples with or without M. bovis challenge were generated using oligonucleotide bovine microarrays containing 43,803 probe sets. These probe sets interrogated the expression levels of ~29,356 transcripts, some of which mapped to known genes. A total of 3,937 probe sets passed the filtering step, consisting of a t-test with an adjusted P-value threshold ≤0.05. At 4 and 24 hpi, 207 and 3,186 unique probe sets, respectively, were significantly differentially expressed (Fig. 1). To investigate the kinetics of gene expression, a total of 420 genes (including genes of unknown function) were found to be differentially expressed. Genes with an upregulated expression (30 out of 135 genes of known function) following exposure of PBMC to M. bovis are listed in Table I, and those with a downregulated expression (84 out of 285 genes of known function) are listed in Table II. As shown in Tables I and II, the genes with a fold change ≥2.5 between 0–4, 4–24 and 0–24 h were listed and divided by functions. Inspection of KEGG pathway annotations for these genes detected their association with the immune system (28%), signal transduction (23%), metabolism (21%), transport and catabolism (8%), genetic information processing (6%), cell growth and death (6%), and other organismal systems (8%). Of the affected genes associated with the immune system, 84.85% were downregulated in PBMCs following M. bovis challenge (Fig. 2). These results indicate a decreased Th1 response [downregulated TNF-α, IFN-γ, and interleukin (IL)-12β], suggesting M. bovis infection may suppress the PBMC immune response.

Figure 1.

Significantly differentially expressed genes at each time point following Mycobacterium bovis challenge of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. The number of upregulated and downregulated genes relative to uninfected controls are shown for each time point sampled. *Adjusted P≤0.05.

Table I.

Genes with upregulated expression (≥2.5-fold) following exposure of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to Mycobacterium bovis.

| Fold change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processes | Symbol | 0–4 h | 4–24 h | 0–24 h | P-value | Gene name |

| Signal transduction | ||||||

| CLEC4E | 1.15 | 7.70 | 8.85 | 0.001 | C-type lectin domain family 4 member E | |

| STAT1 | 0.71 | 2.98 | 2.12 | 0.002 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | |

| DDIT3 | 0.78 | 2.91 | 2.27 | 0.004 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | |

| LDHA | 0.77 | 2.81 | 2.16 | <0.001 | Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) | |

| Immune system | ||||||

| C3AR1 | 0.97 | 6.68 | 6.49 | 0.002 | Complement component 3a receptor 1 | |

| PDK1 | 0.86 | 6.14 | 5.26 | 0.001 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1 | |

| DAPP1 | 0.58 | 4.16 | 2.43 | <0.001 | Dual adaptor of phosphotyrosine and 3-phosphoinositides | |

| RASGRP1 | 0.90 | 3.43 | 3.09 | <0.001 | RAS guanyl releasing protein 1 (calcium and DAG-regulated) | |

| CD244 | 0.94 | 3.29 | 3.08 | <0.001 | CD244 molecule, natural killer cell receptor 2B4 | |

| IL7 | 0.61 | 2.63 | 1.59 | 0.001 | Interleukin-7 precursor | |

| Endocytosis and transport | ||||||

| COLEC11 | 1.14 | 4.78 | 5.44 | <0.001 | Collectin sub-family member 11 | |

| LAMP3 | 0.97 | 2.81 | 2.72 | 0.001 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 | |

| CTSL2 | 0.39 | 2.78 | 1.08 | 0.005 | Cathepsin L2 | |

| EHD1 | 0.90 | 2.58 | 2.33 | 0.001 | EH-domain containing 1 | |

| Inflammation and apoptosis | ||||||

| CDKN2D | 1.21 | 03.15 | 3.82 | <0.001 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D (p19, inhibits CDK4) | |

| CCNG2 | 0.59 | 2.60 | 1.53 | 0.004 | Cyclin G2 | |

| Others | ||||||

| ME1 | 0.95 | 6.79 | 6.48 | 0.002 | Malic enzyme 1 | |

| FBXL3 | 0.90 | 4.21 | 3.80 | <0.001 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 3 | |

| SQLE | 0.97 | 3.52 | 3.41 | 0.003 | Squalene epoxidase | |

| POLD4 | 1.01 | 3.34 | 3.37 | 0.003 | Polymerase (DNA-directed), delta 4 | |

| PTGES | 1.12 | 3.13 | 3.52 | <0.001 | Prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES) | |

| PHOSPHO2 | 1.03 | 3.06 | 3.15 | <0.001 | Phosphatase, orphan 2 | |

| DCK | 1.03 | 2.99 | 3.07 | <0.001 | Deoxycytidine kinase | |

| PLA2G16 | 0.84 | 2.91 | 2.44 | <0.001 | Phospholipase A2, group XVI | |

| CSGALNACT1 | 1.07 | 2.87 | 3.07 | 0.001 | Chondroitisulfate N-acetylgalactosam inyltransferase 1 | |

| NAPB | 0.85 | 2.83 | 2.40 | 0.005 | N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein, beta | |

| PGAP1 | 1.00 | 2.77 | 2.76 | <0.001 | Similar to GPI deacylase | |

| HSD17B7 | 0.93 | 2.65 | 2.47 | 0.002 | Hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 7 | |

| TRIP10 | 1.05 | 2.63 | 2.75 | <0.001 | Thyroid hormone receptor interactor 10 | |

| FDFT1 | 0.92 | 2.62 | 2.41 | <0.001 | Farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 | |

Fold change was calculated as the mean of triplicate experiments.

Table II.

Genes with downregulated expression (≥ 2.5-fold) following exposure of peripheral blood mononuclar cells to Mycobacterium bovis.

| Fold change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processes | Symbol | 0–4 h | 4–24 h | 0–24 h | P-value | Gene name |

| Signal transduction | ||||||

| THBS1 | 1.33 | −27.82 | −20.91 | <0.001 | Thrombospondin 1 | |

| HMOX1 | 1.29 | −10.11 | −7.86 | <0.001 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | |

| FST | 1.19 | −7.82 | −6.59 | <0.001 | Follistatin | |

| FOSL1 | −1.08 | −5.65 | −6.11 | 0.004 | Fos-related antigen 1 (FRA-1) | |

| CD38 | 1.05 | −5.64 | −5.38 | 0.002 | CD38 molecule | |

| GNG4 | 1.06 | −5.21 | −4.93 | <0.001 | Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), gamma 4 | |

| FZD4 | 1.20 | −4.98 | −4.16 | <0.001 | Frizzled homolog 4 | |

| EDN1 | −1.14 | −4.51 | −5.13 | 0.002 | Endothelin 1 | |

| PTAFR | 1.14 | −4.01 | −3.51 | 0.005 | Platelet-activating factor receptor | |

| MRAS | 1.29 | −3.64 | −2.82 | 0.002 | Muscle RAS oncogene homolog | |

| FOS | −1.02 | −3.56 | −3.64 | 0.002 | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | |

| ICOS | −1.30 | −3.06 | −3.99 | <0.001 | Inducible T-cell co-stimulator | |

| FN1 | 1.20 | −2.87 | −2.40 | 0.004 | Fibronectin 1 | |

| NUMBL | 1.24 | −2.83 | −2.28 | 0.002 | Numb homolog (Drosophila)-like | |

| CACNG4 | 1.25 | −2.79 | −2.24 | 0.001 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 4 | |

| PTGS2 | −1.13 | −2.71 | −3.06 | <0.001 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | |

| TCF7L2 | 1.21 | −2.51 | −2.08 | <0.001 | Transcription factor 7-like 2 (T-cell specific, HMG-box) | |

| Immune system | ||||||

| C1QB | 1.21 | −26.31 | −21.76 | 0.002 | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, B chain | |

| PPBP | −1.07 | −17.11 | −18.37 | <0.001 | Pro-platelet basic protein (chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7) | |

| CFB | −1.07 | −16.33 | −17.52 | <0.001 | Complement factor B (CFB) | |

| IFNG | 1.02 | −14.28 | −14.06 | <0.001 | Interferon, gamma | |

| THBD | −1.00 | −14.27 | −14.32 | <0.001 | Thrombomodulin | |

| GZMB | 1.13 | −9.25 | −8.21 | <0.001 | Granzyme B (granzyme 2, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated serine esterase 1) | |

| C1QA | 1.08 | −7.58 | −7.03 | <0.001 | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, A chain | |

| SPP1 | −1.07 | −6.62 | −7.05 | 0.003 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | |

| PLK3 | −1.10 | −5.99 | −6.60 | <0.001 | Polo-like kinase 3 (Drosophila) | |

| F13A1 | 1.07 | −5.12 | −4.79 | 0.002 | Coagulation factor XIII, A1 polypeptide | |

| PLA2G4A | 1.07 | −4.58 | −4.28 | 0.002 | Phospholipase A2, group IVA (cytosolic, calcium-dependent) | |

| CD55 | −1.09 | −4.54 | −4.97 | <0.001 | CD55 molecule, decay accelerating factor for complement (Cromer blood group) | |

| CD14 | 1.49 | −4.41 | −2.96 | <0.001 | CD14 molecule | |

| IL10 | −1.29 | −4.11 | 5.30 | 0.002 | Interleukin 10 | |

| MAP3K8 | −1.17 | −4.02 | −4.70 | <0.001 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 | |

| CCR3 | 1.01 | −3.88 | −3.84 | 0.003 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 3 | |

| CCR4 | −1.06 | −3.63 | −3.85 | 0.002 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 4 | |

| KLRK1 | −1.16 | −3.55 | −4.12 | <0.001 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily K, member 1 | |

| IL2RA | −1.00 | −3.46 | −3.48 | <0.001 | Interleukin 2 receptor, alpha (IL2RA) | |

| CSF1R | 1.32 | −3.41 | −2.58 | <0.001 | Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor precursor | |

| CCR1 | 1.08 | −3.18 | −2.95 | 0.003 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | |

| CCL4 | −1.06 | −3.13 | −3.31 | 0.006 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 (CCL4), | |

| INHBA | 1.04 | −3.13 | −3.02 | 0.002 | Inhibin, beta A | |

| PECAM1 | 1.04 | −3.59 | −3.47 | 0.001 | Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule | |

| TNFRSF25 | −1.10 | −3.08 | −3.40 | <0.001 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 25 | |

| CCL3 | 1.35 | −3.01 | −2.22 | 0.002 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | |

| TLR8 | −1.26 | −2.85 | −3.60 | 0.006 | Toll-like receptor 8 | |

| IL12B | −1.20 | −2.83 | −3.40 | 0.004 | Interleukin 12B | |

| CTSB | −1.06 | −2.79 | −2.97 | 0.003 | Cathepsin B | |

| JAM3 | 1.05 | −2.67 | −2.54 | <0.001 | Junctional adhesion molecule 3 | |

| SIPA1 | 1.07 | −2.61 | −2.43 | 0.003 | Signal-induced proliferation-associated 1 | |

| PGD | −1.16 | −2.54 | −2.95 | 0.004 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | |

| Endocytosis and transport | ||||||

| RAB7B | 1.13 | −4.29 | −3.79 | <0.001 | RAB7B, member RAS oncogene family | |

| CD36 | 1.02 | −3.58 | −3.50 | 0.001 | CD36 molecule (thrombospondin receptor) | |

| ACP2 | 1.00 | −3.56 | −3.54 | <0.001 | Acid phosphatase 2, lysosomal | |

| SORT1 | −1.02 | −3.45 | −3.51 | <0.001 | Sortilin 1 | |

| ACTB | 1.17 | −2.85 | −2.44 | <0.001 | Actin, beta | |

| AP1B1 | 1.03 | −2.78 | −2.71 | <0.001 | Adaptor-related protein complex 1, beta 1 subunit | |

| Inflammation and apoptosis | ||||||

| TNF | −1.02 | −6.07 | −6.18 | <0.001 | Tumor necrosis factor (TNF superfamily, member 2) | |

| IL1RAP | 1.17 | −4.85 | −5.67 | 0.005 | Interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein | |

| IGFBP3 | −1.06 | −3.06 | −3.23 | 0.002 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 | |

| CDKN1C | 1.33 | −2.95 | −2.22 | <0.001 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (p57, Kip2) | |

| AMOTL1 | −1.10 | −2.71 | −2.99 | 0.001 | Angiomotin like 1 | |

| FASLG | −1.19 | −2.62 | 3.12 | <0.001 | Fas ligand | |

| Others | ||||||

| CYP3A4 | −1.04 | −4.65 | −4.83 | 0.002 | Cytochrome P450, subfamily IIIA, polypeptide 4 | |

| B4GALT6 | −1.05 | −4.09 | −4.31 | 0.003 | B4GALT6 protein, transcript variant 2 | |

| TBXAS1 | 1.07 | −4.03 | −3.78 | 0.002 | Thromboxane A synthase 1 | |

| ST8SIA1 | 1.07 | −3.78 | 3.52 | 0.002 | Alpha-N-acetylneuraminide alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase | |

| GAB1 | 1.29 | −3.61 | −4.65 | <0.001 | GRB2-associated binding protein 1 | |

| HSD17B8 | 1.01 | −3.60 | −3.57 | 0.005 | Hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 8 | |

| HS3ST1 | 1.55 | −3.27 | −2.11 | 0.001 | Heparan sulfate (glucosamine) 3-O-sulfotransferase 1 | |

| MMP14 | 1.04 | −3.09 | −2.96 | <0.001 | Matrix metallopeptidase 14 | |

| ITGAD | 1.03 | −2.83 | −2.75 | <0.001 | Integrin, alpha D | |

| TXNDC5 | −1.08 | −3.34 | −3.60 | <0.001 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 precursor | |

| VIM | 1.06 | −2.59 | −2.44 | 0.004 | Vimentin | |

| SDS | −1.23 | −3.93 | −4.85 | <0.001 | Serine dehydratase | |

| EME2 | 1.09 | −2.65 | 2.44 | 0.003 | Endonuclease | |

| SFRS7 | −1.02 | −2.82 | −2.87 | <0.001 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 | |

| NUP160 | 1.15 | −3.01 | −2.62 | 0.001 | Nucleoporin 160kDa | |

| PWP2 | 1.13 | −2.92 | −2.59 | <0.001 | Periodic tryptophan protein 2 homolog | |

| DSE | −1.09 | −2.92 | −3.17 | <0.001 | Dermatan sulfate epimerase | |

| PNPLA4 | 1.10 | −2.83 | −2.57 | <0.001 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 4 | |

| BLVRB | 1.00 | −2.75 | −2.75 | <0.001 | Biliverdin reductase B | |

| CHST2 | 1.04 | −2.75 | −2.64 | <0.001 | Carbohydrate (N-acetylglucosamine-6-O) sulfotransferase 2 | |

| AGPAT3 | 1.08 | −2.63 | −2.43 | <0.001 | 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3 | |

| EXT1 | −1.19 | −2.61 | −3.12 | 0.001 | Exostoses (multiple) 1 | |

| GSTK1 | 1.12 | −2.60 | −2.90 | 0.002 | Glutathione S-transferase kappa 1 | |

Fold change was calculated as the mean of triplicate experiments.

Figure 2.

Profile of differentially expressed genes organized by functional subcategories of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. Based on the number of genes with altered expression, Mycobacterium bovis exposure had the greatest effect on genes associated with the immune response.

Identification of pathways and networks associated with genes affected by M. bovis infection

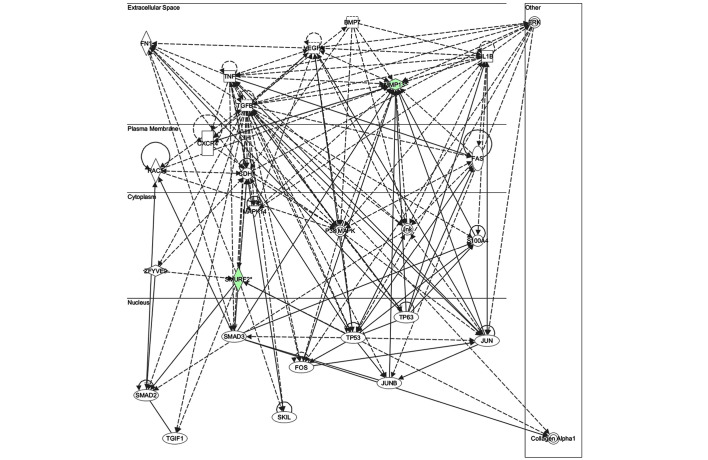

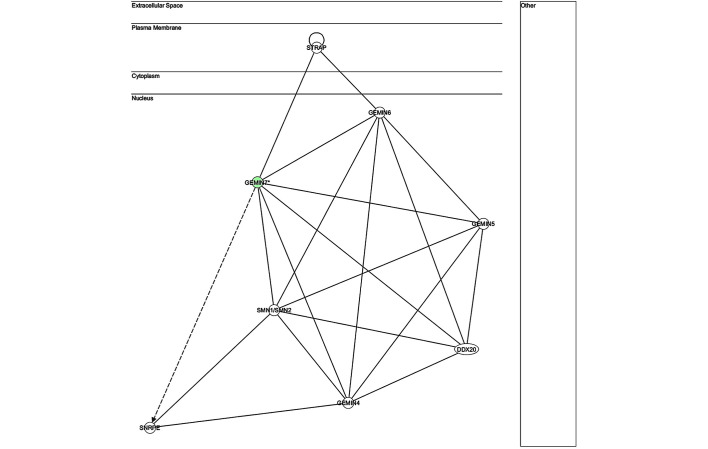

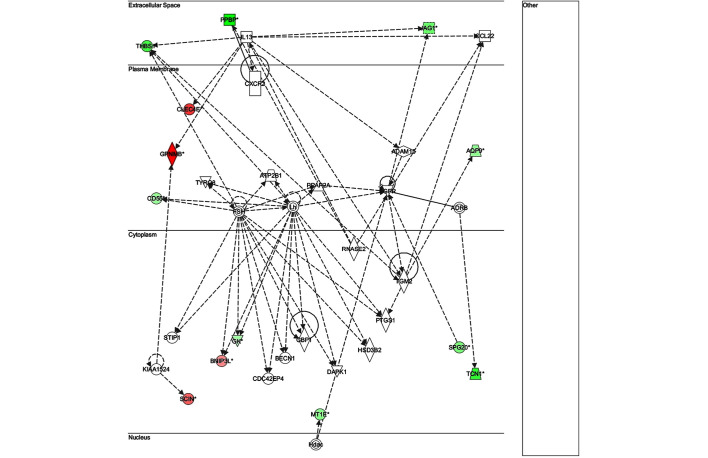

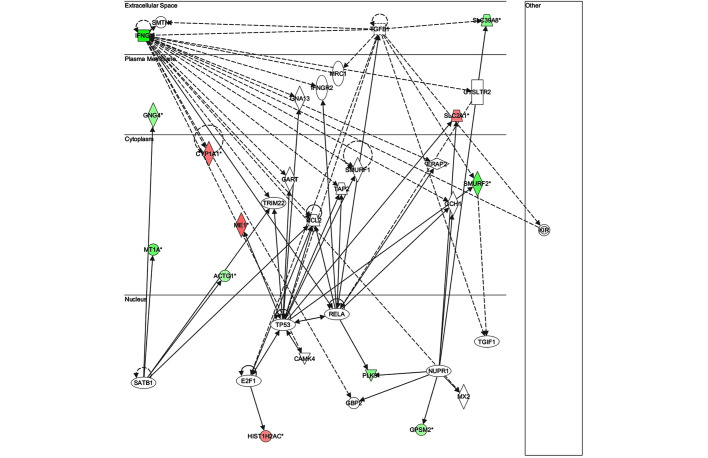

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed on the microarray data to identify the specific biological pathways associated with genes differentially expressed upon M. bovis infection. IPA of the microarray data identified the functional profiles of 15 genes that were differentially expressed between 0 and 4 hpi (Table III), and their associated pathways (Table IV). A total of 91 genes with differential expression between 0 and 24 hpi were selected in the present study for IPA; and the results of the top 28 (greatest change in expression) are shown in Table V. The pathways associated with these genes are shown in Table VI. A map of the network of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 hpi is shown in Figs. 3–6.

Table III.

Ingenuity pathway analysis profile of genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 hours post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

| Symbol | Entrez gene name | Fold change | Network | Location | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLDN3 | Claudin 3 | 3.07 | 3 | Plasma membrane | Transmembrane receptor |

| MMP2 | Matrix metallopeptidase 2 (gelatinase A, 72 kDa gelatinase, 72 kDa type IV collagenase) | 0.11 | 3 | Extracellular space | Peptidase |

| MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | 0.05 | 1 | Cytoplasm | Kinase |

| GEMIN6 | Gem (nuclear organelle) associated protein 6 | −0.09 | 4 | Nucleus | Other |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | −0.09 | 1 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor, beta 1 | −0.13 | 1 | Extracellular space | Growth factor |

| CREB1 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 | −0.51 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | |

| IL1B | Interleukin 1, beta | −0.52 | 1 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| STRAP | Serine/threonine kinase receptor associated protein | −0.60 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Other |

| REM1 | RAS (RAD and GEM)-like GTP-binding 1 | −3.13 | Other | Enzyme | |

| MMP13 | Matrix metallopeptidase 13 (collagenase 3) | −6.25 | 1 | Extracellular space | Peptidase |

| ADCY6 | Adenylate cyclase 6 | −6.67 | 2 | Plasma membrane | Enzyme |

| GEMIN7 | Gem (nuclear organelle) associated protein 7 | −11.11 | 4 | Nucleus | Other |

| SMURF2 | SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | −16.67 | 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| FMO4 | Flavin containing monooxygenase 4 | −32.98 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

Table IV.

Pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 hours post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

| Ingenuity canonical pathway | |−log (p)| | Gene ratioa | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granulocyte adhesion and diapedesis | 2.57 | 1.2E-02 | MMP13, CLDN3 |

| Agranulocyte adhesion and diapedesis | 2.52 | 1.14E-02 | MMP13, CLDN3 |

| Leukocyte extravasation signaling | 2.43 | 1.02E-02 | MMP13, CLDN3 |

| Oncostatin M signaling | 1.78 | 2.94E-02 | MMP13 |

| Inhibition of matrix metalloproteases | 1.73 | 2.63E-02 | MMP13 |

| CDK5 signaling | 1.38 | 1.12E-02 | ADCY6 |

| TGF-β signaling | 1.38 | 1.08E-02 | SMURF2 |

| IL-1 signaling | 1.36 | 9.8E-03 | ADCY6 |

| HIF1α signaling | 1.32 | 9.8E-03 | MMP13 |

| Gαi signaling | 1.24 | 7.81E-03 | ADCY6 |

| eNOS signaling | 1.23 | 7.75E-03 | ADCY6 |

| CXCR4 signaling | 1.15 | 6.25E-03 | ADCY6 |

| Gap junction signaling | 1.15 | 6.41E-03 | ADCY6 |

| Tight junction signaling | 1.14 | 6.37E-03 | CLDN3 |

| PPARα/RXRα activation | 1.11 | 5.75E-03 | ADCY6 |

| RAR activation | 1.09 | 5.59E-03 | ADCY6 |

| LPS/IL-1 mediated inhibition of RXR function | 1.01 | 4.5E-03 | FMO4 |

Number of pathway genes differentially expressed/number of genes in pathway.

Table V.

Ingenuity pathway analysis profile of genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 hours post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

| Symbol | Entrez gene name | Fold change | Network | Location | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPNMB | Glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb | 22.93 | 2 | Plasma membrane | Enzyme |

| AK4 | Adenylate kinase 4 | 19.13 | 4 | Cytoplasm | Kinase |

| KCNH2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag-related), member 2 | 18.27 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Ion channel |

| CLEC4E | C-type lectin domain family 4, member E | 13.36 | 2 | Plasma membrane | Other |

| CLU | Clusterin | 12.13 | 4 | Cytoplasm | Other |

| C3AR1 | Complement component 3a receptor 1 | 7.93 | 1 | Plasma membrane | G-protein coupled receptor |

| Akt | Bos taurus v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 | 2.06 | 4 | Cytoplasm | Group |

| BCL2 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 | −0.29 | 3 | Cytoplasm | Transporter |

| CASP8 | Caspase 8, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | −0.60 | Nucleus | Peptidase | |

| NFKB1 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | −0.80 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | |

| IL1B | Interleukin 1, beta | −1.04 | Extracellular space | Cytokine | |

| FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE, high affinity I, receptor for; gamma polypeptide | −1.98 | Plasma membrane | Transmembrane receptor | |

| CD55 | CD55 molecule, decay accelerating factor for complement (Cromer blood group) | −4.76 | 2 | Plasma membrane | Other |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | −6.45 | 1 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| C1QA | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, A chain | −7.69 | 1 | Extracellular space | Other |

| PLK3 | Polo-like kinase 3 | −8.33 | 3 | Nucleus | Kinase |

| CEBPD | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), delta | −9.09 | 4 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| IL17F | Interleukin 17F | −9.52 | 1 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| GZMB | Granzyme B (granzyme 2, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated serine esterase 1) | −11.11 | 1 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase |

| MMP13 | Matrix metallopeptidase 13 (collagenase 3) | −11.11 | 1 | Extracellular space | Peptidase |

| SMURF2 | SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | −12.50 | 3 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| CFB | Complement factor B | −13.33 | 1 | Extracellular space | Peptidase |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin 1 | −13.33 | 1,2 | Extracellular space | Other |

| FMO4 | Flavin containing monooxygenase 4 | −14.29 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | |

| IFNG | Interferon, gamma | −20.00 | 1,3 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| THBD | Thrombomodulin | −20.00 | 1 | Plasma membrane | Transmembrane receptor |

| IL17RB | Interleukin 17 receptor B | −25.00 | 1 | Plasma membrane | Transmembrane receptor |

| C1QB | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, B chain | −28.57 | 1 | Extracellular space | Other |

Table VI.

Pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 hours post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | |-log (P)| | Gene ratioa | Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses | 3.23E00 | 4.21E-02 | C1QA, C1QB, C3AR1, TNF |

| Production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages | 3.02E00 | 2.69E-02 | IFNG, MAP3K8, TNF, CLU, RBP4 |

| Cytokines mediating communication between immune cells | 2.86E00 | 5.77E-02 | IFNG, IL17F, TNF |

| T helper cell differentiation | 2.55E00 | 4.35E-02 | IFNG, IL17F, TNF |

| VDR/RXR activation | 2.37E00 | 3.85E-02 | IFNG, SPP1, THBD |

| Crosstalk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells | 2.2E00 | 3.3E-02 | IFNG, TNF, ACTG1 |

| Acute phase response signaling | 1.47E00 | 1.73E-02 | CFB, TNF, RBP4 |

| Communication between innate and adaptive immune cells | 1.33E00 | 2.15E-02 | IFNG, TNF |

| PI3K/AKT signaling | 1.03E00 | 1.48E-02 | GAB1, MAP3K8 |

| TNFR2 signaling | 9.51E-01 | 3.12E-02 | TNF |

| Interferon signaling | 8.72E-01 | 2.94E-02 | IFNG |

| Antigen presentation pathway | 8.38E-01 | 2.5E-02 | IFNG |

| Inhibition of matrix metalloproteases | 8.28E-01 | 2.63E-02 | MMP13 |

| NF-κB signaling | 7.96E-01 | 1.14E-02 | MAP3K8, TNF |

| iNOS signaling | 7.78E-01 | 2.13E-02 | IFNG |

| TNFR1 signaling | 7.43E-01 | 1.96E-02 | TNF |

| Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated apoptosis of target cells | 7.27E-01 | 1.92E-02 | GZMB |

| Leukocyte extravasation signaling | 7.08E-01 | 1.02E-02 | MMP13, ACTG1 |

| Death receptor signaling | 6.62E-01 | 1.61E-02 | TNF |

| Activation of IRF by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors | 6.49E-01 | 1.59E-02 | TNF |

| Role of PI3K/AKT signaling in the pathogenesis of influenza | 6.42E-01 | 1.49E-02 | IFNG |

| IL-10 signaling | 6.01E-01 | 1.39E-02 | TNF |

| Apoptosis signaling | 5.06E-01 | 1.09E-02 | TNF |

| Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes | 4.87E-01 | 1.05E-02 | ACTG1 |

Number of pathway genes differentially expressed/number of genes in pathway.

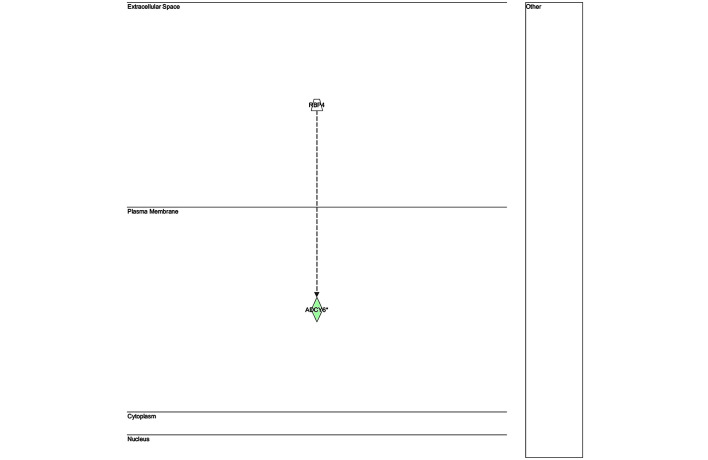

Figure 3.

Network 1 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 6.

Network 4 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

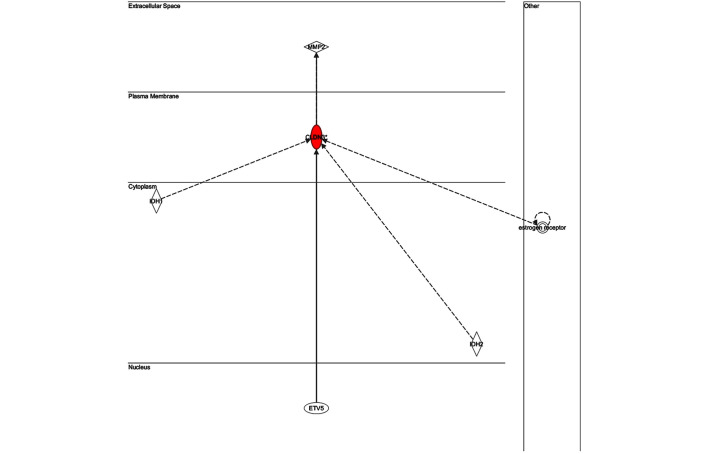

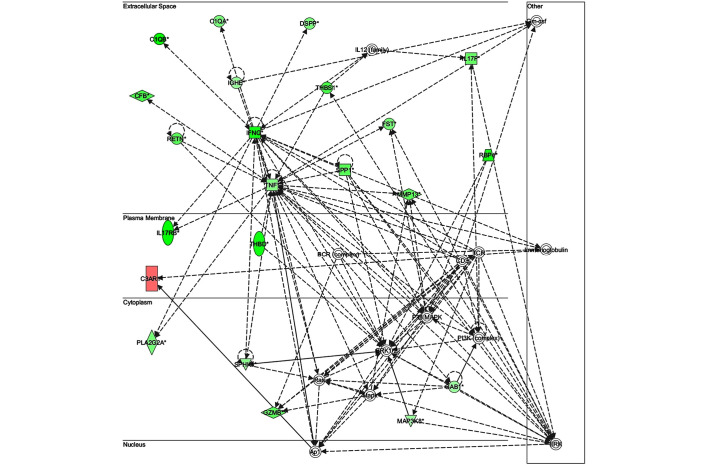

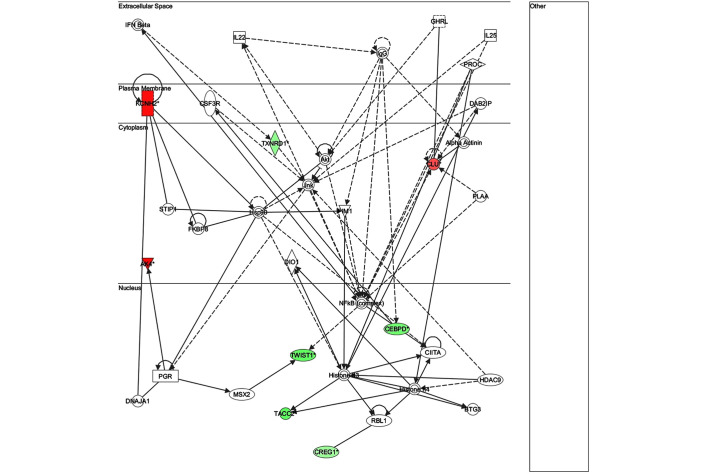

The key genes in network 1 (Fig. 3) were transforming growth factor-β and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)13; both of which are major genes associated with inflammatory responses. There were only two genes in network 2 (Fig. 4): Retinol-binding protein 4 and adenylyl cyclase 6; both of which have known roles in development, particularly embryonic, skeletal and muscular, and so were unlikely to be associated with infection. The key gene in network 3 (Fig. 5) was claudin 3 (CLDN3); as in the case of network 2, this network is predominantly associated with skeletal and muscular development, and therefore has only a weak association with the infection. The key gene in network 4 (Fig. 6) was gem-associated protein 7, which is associated with cell death and survival, and therefore may be associated with the late response to M. bovis infection. The four networks of the pathways comprising genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 hpi are shown in Figs. 7–10. The key gene in network 1 was TNF-α, which interacts with IFN-γ, MMP13, and thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) (Fig. 7). Expression of these four genes was downregulated. TNF-α also interacts with IL-17 receptor B and thrombomodulin, both of which demonstrated downregulated expression. In addition, TNF-α interacts with activating protein-1, which upregulates complement component 3a receptor 1. The key genes in network 2 were luteinizing hormone (LH) and IL-13. IL-13 upregulates C-type lectin domain family 4 member E, and glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb, and downregulates THBS1 and androgen-induced 1 (Fig. 8). The key gene in network 3 was IFN-γ, which regulates the expression of B-cell lymphoma-2 and the nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65 subunit (Fig. 9). The key gene in network 4 was Akt, which regulates the expression of NF-κB, followed by the downregulation of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, delta (Fig. 10).

Figure 4.

Network 2 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 5.

Network 3 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 4 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 7.

Network 1 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 10.

Network 4 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 8.

Network 2 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Figure 9.

Network 3 of pathways involving genes differentially expressed between 0 and 24 h post-infection with Mycobacterium bovis.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that bovine PBMCs responded to in vitro M. bovis infection by undergoing large-scale alterations in gene expression. The expression of 420 genes was shown to significantly differ between 4 and 24 hpi, with 135 upregulated and 285 downregulated genes. Inspection of KEGG pathway annotations for these genes demonstrated that the majority was associated with the immune system, signal transduction, and metabolism. Of the affected genes with immune system functions, 84.85% were downregulated. System pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed the key genes in four different networks to be TNF-α, IFN-γ, LH, IL-13, and NF-κB. These results suggested that M. bovis may suppress the PBMC immune response soon after infection.

The number of differentially expressed PBMC genes increased during the first 24 h following exposure to M. bovis. Changes were observed in 207 unique probe sets at 4 hpi and in 3,186 unique probe sets at 24 hpi. Of these, 420 genes displayed significantly altered expression from 4 to 24 hpi, with expression decreasing for 285 genes and increasing for 135 genes. In addition, the fold-change in expression of the downregulated genes was much greater, as compared with that of upregulated genes. Previous studies of transcriptional responses to M. bovis infection have reported downregulation of the majority of differentially expressed genes (10,12,15,16). In the present study, more genes were suppressed later post-infection (24 h), as compared with earlier (4 h), suggesting the cellular activities involving these genes progressively declined during M. bovis infection.

Inspection of KEGG pathway annotations for the 420 differentially expressed genes revealed their involvement in the immune system (28%), signal transduction (23%), metabolism (21%), transport and catabolism (8%), genetic information processing (6%), cell growth and death (6%), and other organismal systems (8%). Of these genes, >67% (280) exhibited time-dependent decreases in expression associated with signal transduction, immune response, pro-inflammatory cytokines, metabolism, or cell death processes. In addition, 84.85% of the differentially expressed genes associated with immune responses displayed downregulated expression in infected PBMCs. Suppression of host immune response genes is a common finding among studies of gene expression following M. bovis infection (6,12,16). Transcriptome analysis of peripheral blood leukocytes from cattle infected with M. bovis previously detected over-representation of differentially expressed genes associated with the immune response; of these genes, 64.5% showed decreased expression, indicating M. bovis infection may be associated with the suppression of host immune genes (12). Meade et al (16) reported a decrease in the in vivo PBMC expression of key innate immune genes in M. bovis-infected cattle. Subsequent in vivo transcriptional studies of M. bovis-infected cattle demonstrated that PBMC genes associated with immunity, inflammatory responses, and apoptosis were among those with the highest differential expression (10). These in vivo experiments were conducted in animals following the establishment of an infection, ranging from 2–12 months following inoculation. The in vitro data of the present study supports these findings and further reveals that changes in gene expression begin very early in the course of infection.

Notably, M. bovis infection resulted in a decrease in expression of the most important components of the Th1 response: IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-12. The significance of the altered expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α is demonstrated by their mapping to key locations in the pathway networks. These genes are crucial to the host immune response against mycobacteria, including granuloma formation and apoptosis. Signaling via the IFN-γ pathway is required for macrophage activation and granuloma formation (5). Such signaling is dependent on the production of IFN-γ by T-cells; and IFN-γ synthesis requires the cytokine IL-12. Conversely, the observation in the present study of decreased IFN-γ expression differs from a previous study, which reported that the vaccine Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin triggers a Th1-type response (17). In addition, another study reported the increased expression of IFN-γ in PBMC from cattle infected 4 months previously (10). However, these studies observed that genes downstream of IFN-γ were significantly downregulated, suggesting suppression of IFN-γ signaling despite its increased expression. Strain virulence, MOI, cell type, post-infection harvest time, and specific assays used may also underlie these different results.

Apoptosis of infected macrophages is an innate host defense mechanism against intracellular M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. The extrinsic cell death pathway involved in apoptosis is induced by the binding of TNF-α to its receptor on the macrophage surface. Macrophages infected with attenuated strains of pathogenic mycobacteria undergo TNF-α-mediated apoptosis, reducing the viability of intracellular bacilli. Virulent M. tuberculosis strains have been found to suppress macrophage apoptosis (18,19). Previous studies have detected upregulation of programmed cell death signaling genes, including TNF-α, following live M. bovis challenge of bovine macrophages in vitro (6,20). Therefore, it is intriguing that TNF-α was the key gene affected in network 1. Through this network of pathways, TNF-α was shown to interact with IFN-γ, MMP13, and THBS1.

The present study has numerous limitations. The methods did not distinguish between M. bovis-infected cells and M. bovis-exposed cells; therefore, no correlations can be made between gene expression levels and infection rates. The M. bovis cells were not from a standard strain; therefore, some comparisons to other studies may be less reliable. In addition, the present study does not provide further analysis of specific genes indicated by the microarray data. However, the data from this preliminary screening provide a solid foundation for future investigations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing a time-course analysis of global gene expression in bovine PBMCs following in vitro exposure to M. bovis. Our data indicate that extensive alterations in PBMC gene expression may begin early in infection. The majority of the differentially expressed genes were related to immune responses and cell survival. Changes observed in the expression of genes associated with immune responses suggest that M. bovis infection may be associated with the suppression of immune response-related gene expression. In addition, M. bovis infection in PBMCs may suppress apoptosis by interfering with TNF-α signaling. The present study provides valuable information for the further characterization of host responses to M. bovis infection.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan, the Republic of China.

References

- 1.Etter E, Donado P, Jori F, Caron A, Goutard F, Roger F. Risk analysis and bovine tuberculosis, a re-emerging zoonosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1081:61–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1373.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neill SD, Pollock JM, Bryson DB, Hanna J. Pathogenesis of Mycobacterium bovis infection in cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1994;40:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabara E, Kloss CC, Wilson M, Tempelman RJ, Sreevatsan S, Janagama H, Coussens PM. A large-scale study of differential gene expression in monocyte-derived macrophages infected with several strains of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Brief Funct Genomics. 2010;9:220–237. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerrigan AM, Brown GD. Syk-coupled C-type lectins in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders BM, Britton WJ. Life and death in the granuloma: Immunopathology of tuberculosis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:103–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magee DA, Taraktsoglou M, Killick KE, Nalpas NC, Browne JA, Park SD, Conlon KM, Lynn DJ, Hokamp K, Gordon SV, et al. Global gene expression and systems biology analysis of bovine monocyte-derived macrophages in response to in vitro challenge with Mycobacterium bovis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Netea MG, Van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ. Toll-like receptors as an escape mechanism from the host defense. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behar SM, Divangahi M, Remold HG. Evasion of innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Is death an exit strategy? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:668–674. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsik CG, Tellam RL, Worley KC, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Weinstock GM, Adelson DL, Eichler EE, Elnitski L, et al. The genome sequence of taurine cattle: A window to ruminant biology and evolution. Science. 2009;324:522–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1169588. Bovine Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco FC, Soria M, Bianco MV, Bigi F. Transcriptional response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from cattle infected with Mycobacterium bovis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meade KG, Gormley E, O'Farrelly C, Park SD, Costello E, Keane J, Zhao Y, MacHugh DE. Antigen stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from Mycobacterium bovis infected cattle yields evidence for a novel gene expression program. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:447. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killick KE, Browne JA, Park SD, Magee DA, Martin I, Meade KG, Gordon SV, Gormley E, O'Farrelly C, Hokamp K, MacHugh DE. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of peripheral blood leukocytes from cattle infected with Mycobacterium bovis reveals suppression of host immune genes. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:611. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollock JM, Neill SD. Mycobacterium bovis infection and tuberculosis in cattle. Vet J. 2002;163:115–127. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2001.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aranaz A, Liébana E, Mateos A, Dominguez L, Vidal D, Domingo M, Gonzolez O, Rodriguez-Ferri EF, Bunschoten AE, Van Embden JD, Cousins D. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of Mycobacterium bovis strains from cattle and other animals: A tool for studying epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2734–2740. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2734-2740.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meade KG, Gormley E, Park SD, Fitzsimons T, Rosa GJ, Costello E, Keane J, Coussens PM, MacHugh DE. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from Mycobacterium bovis infected cattle after in vitro antigenic stimulation with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD) Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2006;113:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meade KG, Gormley E, Doyle MB, Fitzsimons T, O'Farrelly C, Costello E, Keane J, Zhao Y, MacHugh DE. Innate gene repression associated with Mycobacterium bovis infection in cattle: Toward a gene signature of disease. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:400. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchant A, Goetghebuer T, Ota MO, Wolfe I, Ceesay SJ, De Groote D, Corrah T, Bennett S, Wheeler J, Huygen K, et al. Newborns develop a Th1-type immune response to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination. J Immunol. 1999;163:2249–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Divangahi M, Chen M, Gan H, Desjardins D, Hickman TT, Lee DM, Fortune S, Behar SM, Remold HG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis evades macrophage defenses by inhibiting plasma membrane repair. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:899–906. doi: 10.1038/ni.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Remold HG, Ieong MH, Kornfeld H. Macrophage apoptosis in response to high intracellular burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by a novel caspase-independent pathway. J Immunol. 2006;176:4267–4274. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Widdison S, Watson M, Coffey TJ. Early response of bovine alveolar macrophages to infection with live and heat-killed Mycobacterium bovis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2011;35:580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]