Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) represents a rare form of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder, and the presence of plasma cells in the liver is generally associated with aggressive forms of MM. In the present study, an unusual case of extramedullary plasmacytoma, affecting the liver and vertebrae of a recipient of a renal transplant, is reported. The patient had been previously treated with bortezomib for an MM following renal transplantation, as diagnosed by percutaneous needle biopsy of the hepatic lesion. He was then treated with 5 cycles of RCD regimen (lenalidomide, 25 mg, days 1–21; cyclophosphamide. 50–100 mg, days 1–21; and dexamethasone, 20 mg, days 1, 8, 15 and 22). The patient achieved partial clinical remission without any severe therapy-associated toxicity effects, indicating that lenalidomide is an effective and safe treatment for extramedullary liver plasmacytoma in renal recipients. In conclusion, the present case study indicated that the RCD regimen was effective and safe in the treatment of relapsed and refractory MM.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, renal transplant, extramedullary plasmacytoma, lenalidomide

Introduction

Compared with the general population, recipients of a kidney transplant have an increased risk of developing various types of cancer (associated and non-associated with infections), due to the immunosuppressant treatment that must be maintained in order to prevent and treat acute rejection of the organ (1). The incidence of secondary cancer increases with the time from the transplant (2). Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLDs) are frequent in patients who receive immunosuppressants, including anti-thymocyte and -lymphocyte globulins or muromonab-CD3, or those who are infected de novo by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) through the transplanted kidney (3). PTLDs may present early or late; be nodal, extranodal, polymorphic or monomorphic; and follow an indolent or aggressive clinical course (3). In contrast to classical PTLDs, there are limited studies on plasma cell malignancies that occur following solid organ transplantation. Multiple myeloma (MM) represents ≤4% of all PTLDs, and is associated with a poor response to discontinuation of immunosuppression and conventional therapy, and a short median survival rate (4,5). Generally, the presence of plasma cells in the liver is associated with aggressive forms of MM (6,7). In the present study, the case of a patient who developed post-transplant MM with extramedullary liver plasmacytoma 11 years following renal transplantation, and was successfully treated with lenalidomide, is reported.

Case report

In February 2012, a 45-year-old female was admitted to The First People's Hospital of Changzhou (Changzhou, China) with complaints of pain in the left shoulder. Due to chronic renal failure, the patient had received a cadaveric kidney transplantation at the same hospital on November 2nd 2001, and was subsequently administered immunosuppression composed of 250 mg/day cyclosporine, 50 mg/day azathioprine and 25 mg/day prednisone, in a dose-tapering manner. From June 2002, the patient received 200 mg/day cyclosporine for maintenance therapy to prevent renal rejection. The patient exhibited normal renal function during the follow-up period.

In March 2008, the patient developed a left nasal obstruction. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a soft tissue mass in the left nasal cavity, which was surgically excised. The post-operative histological study confirmed the presence of extramedullary plasmacytoma, and immunochemical examination demonstrated the specimen to be CD79α+, partially CD138+, CD20−, CD3−, CD45RO−, vimentin+, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)−, cytokeratin AE1/3− and 50% Ki-67+. Treatment with cyclosporine and azathioprine was discontinued, and the patient was administered instead rapamycin (2 mg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; 1 mg twice daily) to prevent renal rejection.

From March 26th to May 14th 2008, the patient received local radiotherapy in the bilateral nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus and maxillary sinus at a total dose of 48 Gy, and continued receiving immunosuppressants (rapamycin and MMF). During the follow-up period, the patient displayed normal renal function.

In February 2012, the patient reported idiopathic pain in the left shoulder. CT scan revealed marked bone destruction of the left scapula and reactive bone formation at the right tenth rib. Positron emission tomography-CT scan revealed high metabolism of 18fluorodeoxyglucose at the left scapula, with a standardized uptake value of 5.5, in addition to bone destruction. Consequently, the patient was subjected to surgery, and postoperative pathological examination suggested plasma cell myeloma, while immunohistochemical staining indicated the specimen to be CD20−, CD3−, CD38+, CD138+, partially CD79α+, EMA−, melanoma associated antigen mutated 1 (MUM1)− and <5% Ki-67+. Bone marrow smear identified 2% mature plasma cells with normal female chromosome karyotype. Interphase fluorescence chromosomal in situ hybridization (FISH) of the bone marrow cells revealed no gene abnormalities in 1q21, RB1, P53, D13S319 and IgH. The serum concentrations of IgG and λ-light chain were 43.8 g/l and 4,930 mg/dl, respectively. Serum protein electrophoresis disclosed a monoclonal spike in the γ-globulin region, whereas urine electrophoresis revealed no monoclonal spike. Serum immunofixation electrophoresis confirmed the presence of an IgG-λ chain monoclonal M component. The renal function and the levels of calcium, hemoglobin, serum albumin, β2-microglobulin and lactate dehydrogenase were normal. No significant alteration was detected in the titers of anti-cytomegalovirus, -EBV or -hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) antibodies. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with post-renal-transplantation secondary MM IgG-λ chain-type, group A and stage I, according to the International Staging System (8). The patient refused treatment with the novel agent bortezomib, due to the high cost, and instead, the patient received modified VADT regimen (vincristine, 0.4 mg, days 1–4; doxorubicin, 10 mg, days 1–4; dexamethasone, 40 mg, days 1–4; and thalidomide, 50–150 mg, days 1–28) for a total of 3 cycles (28 days/cycle).

The patient experienced clinical complete remission in June 2012, and exhibited negative serum immunofixation electrophoresis, 2% mature plasma cells in the bone marrow smear and no hypercalcemia, renal failure or anemia. Next, the patient received a fourth cycle of VADT regimen, followed by 3 cycles (28 days/cycle) of TD regimen (thalidomide, 100 mg, days 1–28; and dexamethasone, 40 mg, days 1–4), as maintenance therapy. During the chemotherapy treatment, the patient was administered a reduced dose of immunosuppressive therapy (rapamycin, 2 mg/day; and MMF, 1.0 g twice daily, tapered to 0.5 g twice daily). During the follow-up, the patient underwent monthly urine analysis, and the measurements of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum Igs and light chain remained unaltered.

In March 2013, during a routine follow-up, increased levels of serum IgG (28 g/l) were detected, which were confirmed to be M protein by serum immunofixation electrophoresis, suggesting asymptomatic relapse of MM. In consequence, the patient was again advised to receive novel therapeutic agents such as bortezomib or lenalidomide, but the patient selected to receive 3 cycles of the previous VADT regimen. However, the patient's condition gradually deteriorated, and in June 2013, levels of serum IgG increased to 57 g/l, with positive serum immunofixation electrophoresis, indicating that the VADT regimen was no longer effective to treat the relapse. Therefore, the patient was administered novel agents for rescue therapy. On July 26th, August 23rd, September 19th and October 25th 2013, the patient received a CyBorDT regimen (cyclophosphamide, 300 mg/m2, days 1,8; bortezomib, 1.3 mg/m2, days 1,4,8,11; dexamethasone, 20 mg, days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11 and 12; and thalidomide, 100 mg, days 1–21) for 4 cycles (21 days/cycle). The subsequent evaluation demonstrated negative serum immunofixation electrophoresis with normal IgG levels and absence of abnormal plasma cells in bone marrow smear. Thus, the patient experienced a complete clinical remission for the second time in November 2013. The patient then accepted TD regimen instead of bortezomib for maintenance therapy, followed by monthly routine laboratory investigations, including ultrasonography of the abdomen, which remained unaltered.

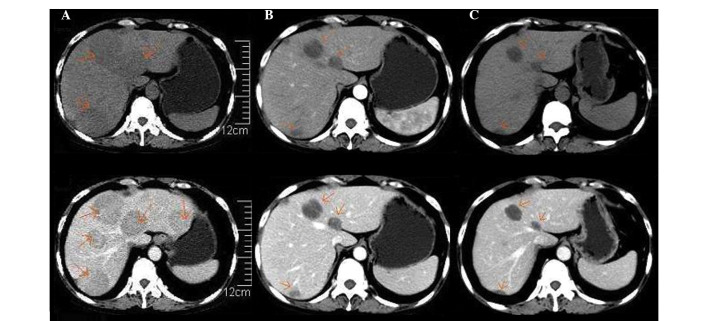

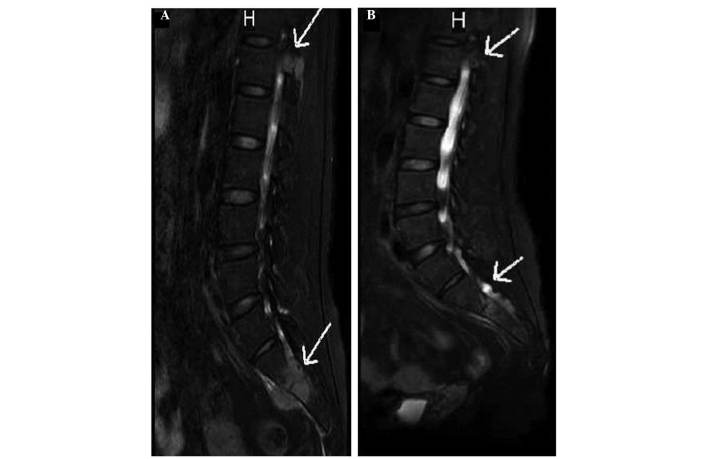

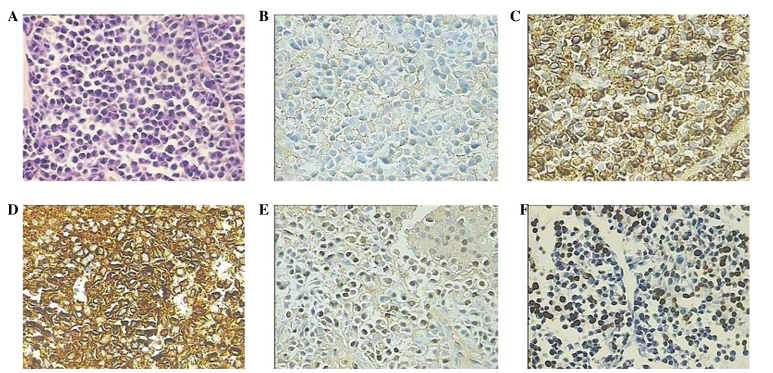

However, 3 months later, in early February 2014, the patient suddenly experienced fever with a temperature of 38.7°C and onset of fatigue, progressive lumbago and non-tender skin mass of the submaxilla. The subsequent abdominal ultrasound identified a diffused hypoechoic lesion in the liver, with a maximum diameter of 8.0×6.5 cm. Full blood count examination demonstrated levels of hemoglobin (84 g/l), hematocrit (35.6%), mean corpuscular volume (86 fl), white blood cells (8.79) and platelets (134×109 cells/l). The results of the liver function tests were in the normal range. The levels of serum total protein were 28 g/l, and protein electrophoresis detected the presence of a monoclonal band in the γ region, which was identified as IgG-λ by immunofixation. Markers for hepatitis C and B virus and serum anti-EBV antibody were negative. Upper abdominal non-enhanced CT scan indicated the presence in the hepatic parenchyma of multiple round-shaped and well-defined lesions of variable sizes with low attenuations. Following administration of contrast agents, the enhancements of the lesions appeared mild and heterogeneous. Based on the clinical information available, these observations were considered to be due to myeloma (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar vertebrae detected the presence of a soft mass and multiple patchy lesions with high attenuations in the T12 thoracic and L1-L4 lumbar vertebrae, and swelling of the spine, spinal accessory, S1, S2 and soft tissue around S1 and S2 (Fig. 2A). Therefore, a CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of the hepatic lesion was performed, and the histological study demonstrated diffused proliferation of plasma cells by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The immunochemical examination demonstrated the specimen to be CD20−, CD3−, CD38+, CD138+, κ+<λ+, EBV+, MUM1+ and ~30–40% Ki67+, which was indicative of extramedullary liver plasmacytoma (Fig. 3). The bone marrow aspirate revealed 6% plasma cell infiltration, and CD138 sorting interphase FISH of bone marrow cells detected 1q21 amplification. Furthermore, increased levels of serum IgG (62 g/l) were measured, which were confirmed to correspond to M protein by serum immunofixation electrophoresis.

Figure 1.

Differences observed in the upper abdominal CT scan images performed prior and subsequent to lenalidomide therapy. (A) non-enhanced (top) and enhanced (bottom) CT preceding lenalidomide therapy, performed February 25th 2014. Multiple round-shaped and well-defined lesions of different sizes with low attenuations were present in the hepatic parenchyma on non-enhanced CT. Following the administration of contrast reagents, the enhancements of the lesions were mild and heterogeneous. (B) Non-enhanced (top) and enhanced (bottom) CT subsequent to 4 cycles of RCD regimen therapy (July 1st 2014). A reduction in the number and size of the round-shaped lesions in the hepatic parenchyma was observed, compared with prior to treatment. (C) Non-enhanced (top) and enhanced (bottom) CT following 5 cycles of RCD regimen (August 25th 2014). Further reduction in the size of the round-shaped lesions present in the hepatic parenchyma was observed, although the lesions did not disappear completely. CT, computed tomography; RCD regimen, lenalidomide, 25 mg, days 1–21; cyclophosphamide, 50 mg, days 1–21; and dexamethasone, 20 mg, days 1, 8, 15 and 22; 28 days/cycle.

Figure 2.

Differences in MRI images of the lumbar vertebrae prior and subsequent to lenalidomide therapy. (A) MRI preceding lenalidomide therapy (March 11th 2014). A soft mass and multiple patchy lesions with high attenuations were clearly observed in the T12 thoracic and L1-L4 lumbar vertebrae, in addition to swelling of the spine, spinal accessory, S1, S2 and soft tissue around S1 and S2. (B) MRI subsequent to 5 cycles of RCD regimen, conducted August 26th 2014. Alleviated swelling of the soft tissue around S1 and S2 was observed. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RCD regimen, lenalidomide, 25 mg, days 1–21; cyclophosphamide, 50 mg, days 1–21; and dexamethasone, 20 mg, days 1, 8, 15 and 22; 28 days/cycle. H, head.

Figure 3.

Histopathological features of the percutaneous needle biopsy of the hepatic lesion. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining identified the presence of plasma cells. (B) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the plasma cells were negative for CD20, but positive for myeloma markers (C) CD38 and (D) CD138 and partially positive for (E) multiple myeloma oncogene 1. (F) In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA was positive. Magnification, ×400. CD, cluster of differentiation.

The patient experienced a rapid relapse 3 months subsequent in February 2014 to the CyBorD regimen, thus, the patient was initiated instead on an RCD regimen (lenalidomide, 25 mg, days 1–21; cyclophosphamide, 50 mg, days 1–21; dexamethasone, 20 mg, days 1, 8, 15 and 22) for 2 cycles (28 days/cycle), from March 14th to May 10th 2014. The next re-evaluation demonstrated that the levels of serum IgG had reduced to 27 g/l, and ultrasonography indicated that the hepatic mass had markedly reduced in size to 6.8×5.5 cm, indicating that the extramedullary liver plasmacytoma was sensitive to the RCD regimen.

Subsequently, the patient received third and fourth cycles of RCD, and the following upper abdominal CT scan, performed July 1st 2014, revealed that the extramedullary liver plasmacytoma had markedly reduced (Fig. 1B), while the levels of hemoglobin and serum IgG were 114 and 13.6 g/l, respectively. During the fourth cycle of RCD, the patient experienced transient agranulocytosis with pulmonary infection. Once the infection had been controlled, the patient did not present symptoms of fever or lumbago. Furthermore, the patient experienced a recovery of myelosuppression, indicating that the patient had achieved partial remission following 4 cycles of RCD regimen.

On August 25th 2014, the patient received the fifth cycle of RCD, and the subsequent abdominal CT demonstrated a further reduction in size, although no complete disappearance, of the round-shaped lesions present in the hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 1C). On August 26th 2014, lumbar vertebrae MRI disclosed a marked reduction of the soft tissue mass in T12 and alleviated swelling of the soft tissue around S1 and S2 (Fig. 2B). Currently, the patient is undergoing outpatient follow-up and receiving RCD regimen for maintenance therapy.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First People's Hospital of Changzhou, Third Affiliated Hospital of Suzhou University (Changzhou, P.R. China).

Discussion

Secondary cancer is a major complication of renal transplant, due to the immunosuppressant treatment required for preventing renal rejection. Secondary cancer following renal transplant results in significant rate of short- and long-term mortality, accounting for 30% of mortalities among renal transplant recipients with a follow-up >20 years (2,9–11). PTLD is a potentially fatal complication of solid organ transplantation, and comprises various lymphoid lesions, ranging from polymorphous reactive proliferations to monomorphous malignant lymphomas (12,13). The majority of these disorders are considered to be driven by EBV infection and subsequent proliferation of B cells in a weakened host. Previous studies have detected EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in the neoplastic cells of the host, suggesting the implication of the EBV genome in the pathogenesis of PTLD (2). EBV-naïve patients who receive an organ from an EBV-infected donor present the highest risk of developing PTLD (10). There are several treatments available for PTLD, including reduced immunosuppression, surgical excision, chemoradiotherapy, anti-CD20 antibody therapy and infusion of EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells, all with variable results (13).

Post-transplantation plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs) are a monomorphous type of PTLD derived from plasma cells, which are the mature, terminally differentiated B cells responsible for the production of antibodies (14). Clinically, 2 diagnostic categories of PCN are recognized: MM, which arises in the bone marrow; and plasmacytoma, which presents as an isolated tumor of plasma cells. Patients with plasmacytoma are commonly diagnosed with MM within months to a few years, which indicates that these conditions are associated (2). Thus far, post-transplantation PCNs have been observed in recipients of solid organ transplantation, but not in recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (4,5,15). Compared with lymphoma, and in particular diffused large B cell lymphoma, post-transplantation PCN is rarely observed, and it accounts for the mortality of 0.24–0.69% of recipients of solid organ transplantation (4,5,15). Unlike non-post-transplantation PCN, post-transplantation PCN occurs in recipients of different ages, including children (16–18). Potential association factors that contribute to post-transplantation PCN have been suggested as follows: i) Old age of the recipient; ii) deceased donor; iii) onset of EBV infection post-transplantation; iv) HCV infection in the recipient; and v) administration of anti-thymocyte or -lymphocyte globulins following solid organ transplantation (4,15).

The incidence of MM is rare in renal graft recipients, despite the frequent findings of monoclonal gammopathies following transplantation (19,20). Sun et al (21) reported 3 cases of plasma cell myeloma PTLD that exhibited clinical, radiological and pathological features of conventional plasma cell myeloma, and Tcheng et al (16) reported the occurrence of EBV-associated post-transplant MM in a 16-year-old male. Plasmacytoma is a tumor of terminally differentiated monoclonal plasma cells, and a frequent complication of MM, appearing at diagnosis or during disease progression (5,20–23). Post-transplant plasmacytomas have been described at several sites, including the allograft, skin, peritoneum, gastrointestinal tract and gingiva. To the best of our knowledge, extramedullary plasmacytoma of liver is associated with aggressive forms of MM, and its presumptive ante mortem diagnosis is often based on clinical findings, such as hepatomegaly and alterations of the liver function detected by laboratory tests. Cases of myeloma with involvement of the liver have been previously reported (24). In the present case report, the patient developed nasal plasmacytoma 7 years following renal transplantation, and experienced relapsed MM with extramedullary liver plasmacytoma 4 years subsequent to this. The patient did not exhibit a large number of abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow cells, in agreement with previous studies (5,20,22,23). In this case, deceased donor and EBV infection are the 2 major association factors for the post-transplantation PCN observed in the patient.

Various treatment options currently exist for eligible patients with MM, including induction therapy, which usually involves novel biologic agents, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (25). CyBorD regimen (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone) has been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of MM, and produces a rapid and complete hematological response in the majority of patients (26). However, this treatment is generally not considered curative, and relapses usually occur. To the best of our knowledge, extramedullary relapse is an uncommon presentation, and relapses that involve the liver have rarely been described (24). Extramedullary plasmacytoma confers a poor prognosis, since it is resistant to conventional treatments, due to its distinct molecular and histological features (27–29). There are very limited data from randomized trials regarding the most appropriate systemic treatment for extramedullary plasmacytoma. Previous case reports suggested that lenalidomide is an effective agent, in combination with dexamethasone, and previous cases of MM relapse following autologous stem cell transplant presenting with diffuse pulmonary nodules exhibited good response to the treatment with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide (27–31).

Au et al (32) reported a case of PTLD presenting as an EBV-associated nasal plasmacytoma in a renal allograft recipient 13 years following transplantation. In order to treat the condition, the authors conducted a non-myeloablative HSCT with peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells from the kidney donor. In their report, Au et al (32) described the occurrence, in a renal allograft recipient, of an MM with extramedullary liver plasmacytoma. In the case of the patient in the present study, the existence of nasal, scapula and liver plasmacytoma was confirmed by post-operative histopathological examination and CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of the hepatic lesion, despite the clinical findings of multiple hepatic masses. FISH analysis for EBER was positive in the hepatic lesion, indicating that the PCN was associated with EBV infection. Following the occurrence of a second relapse, CyBorDT regimen was initiated, which resulted in a fast and positive clinical response, in agreement with previous literature reports (26). However, the patient experienced a third relapse with extramedullary liver plasmacytoma 3 months later, and in consequence, the RCD regimen was initiated to avoid bortezomib resistance. The RCD was combined with intermittent ganciclovir for EBV infection. The patient experienced partial remission, suggesting that the novel immunomodulator lenalidomide is an effective agent to treat extramedullary liver plasmacytoma. However, this treatment is generally not considered curative, and relapses may occur. Therefore, auto-transplantation or non-myeloablative HSCT should be considered in the future.

In summary, the unusual case reported in the present study raises several notable questions with regards to the pathogenesis, clinical behavior and treatment of post-transplant extramedullary liver plasmacytoma. Additional studies are required to establish the appropriate management of this condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Changqing Lu and Dr Tongbin Chen for their help with the pathological analyses. The present study was supported by the 135th opening project of Jiangsu, China (grant no. KF200947).

References

- 1.Penn I. Cancers complicating organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1767–1769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012203232510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrés A. Cancer incidence after immunosuppressive treatment following kidney transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;56:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caillard S, Dharnidharka V, Agodoa L, Bohen E, Abbott K. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders after renal transplantation in the United States in era of modern immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2005;80:1233–1243. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000179639.98338.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engels EA, Clarke CA, Pfeiffer RM, Lynch CF, Weisenburger DD, Gibson TM, Landgren O, Morton LM. Plasma cell neoplasms in US solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1523–1532. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karuturi M, Shah N, Frank D, Fasan O, Reshef R, Ahya VN, Bromberg M, Faust T, Goral S, Schuster SJ, et al. Plasmacytic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder: A case series of nine patients. Transpl Int. 2013;26:616–622. doi: 10.1111/tri.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueda K, Matsui H, Watanabe T, Seki J, Ichinohe T, Tsuji Y, Matsumura K, Sawai Y, Ida H, Ueda Y, Chiba T. Spontaneous rupture of liver plasmacytoma mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Intern Med. 2010;49:653–657. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Maaroufi H, Doghmi K, Rharrassi I, Mikdame M. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the liver. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2012;5:172–173. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2012.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley JJ, Barlogie B, Bladé J, Boccadoro M, Child JA, Avet-Loiseau H, Kyle RA, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahony JF, Caterson RJ, Coulshed S, Stewart JH, Sheil AG. Twenty and 25 years survival after cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2154–2155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris NL, Swerdlow SH, Frizzera G, et al. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, editors. Pathology and Genetics: Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001. pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis NF, McLoughlin LC, Dowling C, Power R, Mohan P, Hickey D, Smyth G, Eng M, Little DM. Incidence and long-term outcomes of squamous cell bladder cancer after deceased donor renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:E665–E668. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branco F, Cavadas V, Osório L, Carvalho F, Martins L, Dias L, Castro-Henriques A, Lima E. The incidence of cancer and potential role of sirolimus immunosuppression conversion on mortality among a single-center renal transplantation cohort of 1,816 patients. Transplant Proc 2011. 2011;43:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knight JS, Tsodikov A, Cibrik DM, Ross CW, Kaminski MS, Blayney DW. Lymphoma after solid organ transplantation: Risk, response to therapy, and survival at a transplantation center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3354–3362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna RW, Kyle RA, Kuehl RA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Coupland RW. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. Plasma cell neoplasms; pp. 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caillard S, Agodoa LY, Bohen EM, Abbott KC. Myeloma, Hodgkin disease, and lymphoid leukemia after renal transplantation: Characteristics, risk factors and prognosis. Transplantation. 2006;81:888–895. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203554.54242.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tcheng WY, Said J, Hall T, Al-Akash S, Malogolowkin M, Feig SA. Post-transplant multiple myeloma in a pediatric renal transplant patient. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:218–223. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry AM, Aoun P, Coulter DW, Sanger WG, Grant WJ, Coccia PF. Early onset, EBV− PTLD in pediatric liver-small bowel transplantation recipients: A spectrum of plasma cell neoplasms with favorable prognosis. Blood. 2013;121:1377–1383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plant AS, Venick RS, Farmer DG, Upadhyay S, Said J, Kempert P. Plasmacytoma-like post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder seen in pediatric combined liver and intestinal transplant recipients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:E137–E139. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renoult E, Bertrand F, Kessler M. Monoclonal gammopathies in HBsAg-positive patients with renal transplants. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805053181815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radl J, Valentijn RM, Haaijman JJ, Paul LC. Monoclonal gammapathies in patients undergoing immunosuppressive treatment after renal transplantation. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1985;37:98–102. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(85)90140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X, Peterson LC, Gong Y, Traynor AE, Nelson BP. Post-transplant plasma cell myeloma and polymorphic lymphoproliferative disorder with monoclonal serum protein occurring in solid organ transplant recipients. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:389–394. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richendollar BG, Hsi ED, Cook JR. Extramedullary plasmacytoma-like post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: Clinical and pathologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:581–588. doi: 10.1309/AJCPX70TIHETNBRL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trappe R, Zimmermann H, Fink S, Reinke P, Dreyling M, Pascher A, Lehmkuhl H, Gärtner B, Anagnostopoulos I, Riess H. Plasmacytoma-like post-transplant lympho-proliferative disorder, a rare subtype of monomorphic B-cell post-transplant, lympho-proliferation is associated with a favorable outcome in localized as well as in advanced disease: A prospective analysis of 8 cases. Haematologica. 2011;96:1067–1071. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.039214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrucci MT, Tirindelli MC, De Muro M, Martini V, Levi A, Mandelli F. Extramedullary liver plasmacytoma a rare presentation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:1075–1076. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000067882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gertz MA, Dingli D. How we manage autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2014;124:882–890. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-544759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikhael JR, Schuster SR, Jimenez-Zepeda VH, Bello N, Spong J, Reeder CB, Stewart AK, Bergsagel PL, Fonseca R. Cyclophosphamide-bortezomib-dexamethasone (CyBorD) produces rapid and complete hematologic response in patients with AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2012;119:4391–4394. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakazato T, Mihara A, Ito C, Sanada Y, Aisa Y. Lenalidomide is active for extramedullary disease in refractory multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:473–474. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito C, Aisa Y, Mihara A, Nakazato T. Lenalidomide is effective for the treatment of bortezomib-resistant extramedullary disease in patients with multiple myeloma: Report of 2 cases. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:83–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saboo SS, Fennessy F, Benajiba L, Laubach J, Anderson KC, Richardson PG. Imaging features of extramedullary, relapsed, and refractory multiple myeloma involving the liver across treatment with cyclophosphamide, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e175–e179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calvo-Villas JM, Alegre A, Calle C, Hernández MT, García-Sánchez R, Ramirez G. GEM-PETHEMA/Spanish Myeloma Group, Spain: Lenalidomide is effective for extramedullary disease in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87:281–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumrall B, Diethelm L, Brown A., Jr Multiple myeloma relapse following autologous stem cell transplant presenting with diffuse pulmonary nodules. Ochsner J. 2013;13:553–557. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Au WY, Lie AK, Chan EC, Pang A, Ma SK, Choy C, Kwong YL. Treatment of postrenal transplantation lymphoproliferative disease manifesting as plasmacytoma with nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from the same kidney donor. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:283–286. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]